Chapter Twenty-Four: The Triumvirate

Well, grad school is pretty draining, but on the other hand, writing and researching for this is a good distraction from all the work I'm dealing with. So much so I had most of this done on Monday, but wanted to fine-tune it a bit more. Here's a look at Eldon's Britain, and Chapter 25 will return us to the Ottoman Empire in the wake of Naxos. Enjoy!

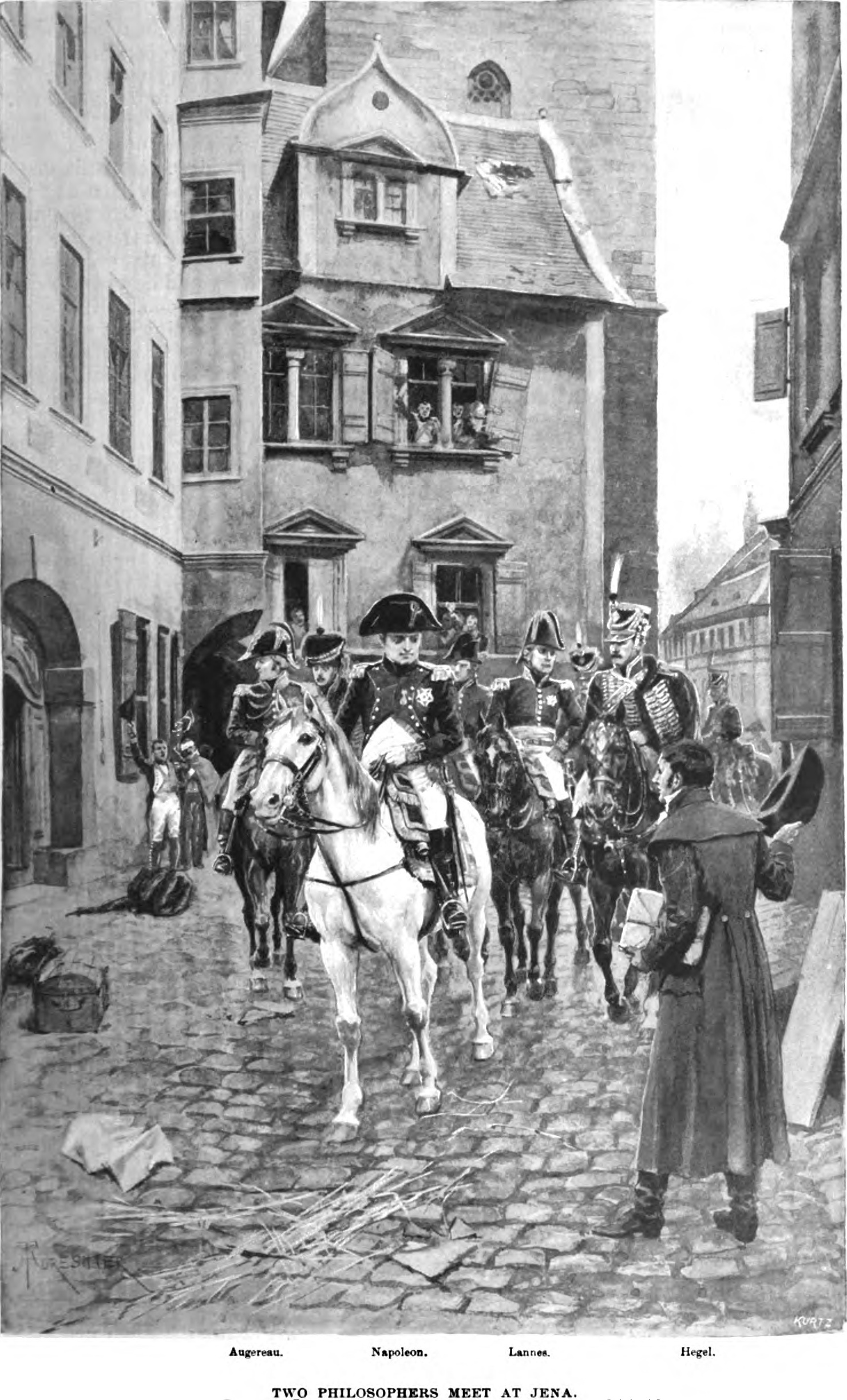

If the Canning Ministry, with its tentative and haphazard stabs at social reform, represented listlessness in post-Madrid Britain, then the counter-revolutionary tenor of Lord Eldon’s government marked the first effort by London to take stock of the post-Napoleonic world. For the most part, this meant increased repression of dissent at home, combined with measured isolation from the outside world, and an aversion to high-stakes foreign entanglements.

Eldon’s foreign policy may seem puzzling on initial inspection. Certainly, he had supported the war against Napoleon with all due zeal, so his moves towards reconciliation with the Emperor while in office present a paradox. There are two main reasons for the Prime Minister’s caution. First, he felt that Britain was ill-prepared for another conflict, burdened as it still was by war debts, industrial discontent, and a sluggish economic recovery.

“Men delude themselves by supposing that war contains only a proclamation, a battle, a victory, and a triumph,” he wrote. “Of the soldiers’ widows and the soldiers’ orphans, after the husbands and fathers are buried, the survivors know nothing.” [1]

Perhaps more importantly, Eldon and his allies saw the foreign stage from a different perspective than Canning or Castlereagh had. The balance of power on the Continent had decisively shifted in France’s favor, and the High Tories saw few prospects of changing that in the foreseeable future. With that painful truth in mind, they instead prioritized ideological threats. To them, revolution was a contagion, as evidenced by the spread of republican fervor from America to France, and from there to the Netherlands, to Poland, to Latin America, to Spain, and to Greece. And with the example of Arthur Thistlewood, they couldn’t dismiss the possibility that Britain was equally vulnerable.

Because of this, the Eldon Ministry cooperated with France and Austria in an effort to counteract revolutionary movements on the Continent. The primary success from this alignment was the restoration of the Bourbons to Spain. These efforts bore a heavy cost, however; with London unwilling to check him, the Emperor strengthened his hand in the Mediterranean through the 1820’s, while also installing a Francophilic monarch on the throne in Madrid.

This tradeoff was a calculated risk on Eldon’s part. A painstaking study conducted by Sir John Kinneir examined the threat France posed to British India, concluding that the Persian Gulf would be a poor staging ground for such an offensive. [2] Because of this, the Eldon government felt safe allowing French maneuvering in the Mediterranean, confident that it posed little threat to their interests. And the more Napoleon was steered into suppressing revolutionary movements, the less credibility the Emperor would enjoy among liberal circles across the Continent. French self-interest could thus be used to box them into a more conservative role in European politics.

Domestically, many historians have drawn comparisons between the rise of the High Tories and the Second Terror that engulfed France half a century later. In both cases, movements for social change and the disappointment of a failed war led to widespread unrest, culminating in acts of shocking political violence. After that, a reactionary backlash ensued, with a pliant press and public empowering the national government to purge society of its cancers, with horrific results.

To be sure, Lord Eldon and his allies lacked the mad ambition and obliterationary zeal of the clique that governed the late French Empire. [3] As a result, the crackdown in 1820’s Britain was far more tempered. Nevertheless, a crackdown it was, with the remnants of the Spenceans and the Luddites either executed, exiled to Australia, or forced deep underground. In addition, Sidmouth’s Six Acts banned events that offered weapons training without government sanction, limited bail for defendants, and gave local authorities the power to search and seize weapons, as well as disperse public meetings concerned with either church or state. Despite several of these laws including sunset provisions, the government made sure to renew all six statutes whenever they came close to expiring. [4]

Despite this repression of violent agitators, political opposition and dissent was still permitted, in several different forms. In Parliament, the opposition was comprised of three main factions. The first of these were the Whigs, who had finally ousted George Ponsonby after their disastrous performance in 1820. His replacement, Charles Grey, proved a more vigorous critic of the ruling government, castigating Viscount Sidmouth and Spencer Perceval for sabotaging Canning’s Emancipation initiative and “slighting the memory of the former Minister, angling for power before his body was even cold.”

Charles Grey provided the most vigorous leadership the Whigs had seen since the death of Charles James Fox.

For their part, Canning’s surviving supporters also opposed the High Tories. Their program was less ambitious than Grey’s, but they also supported Emancipation. As well, the Canningite Tories, now led by Lord Melbourne, called for repeal of the Corn Law, arguing that an end to trade barriers would enable British goods to contest the French in the European market.

Lastly, there was a small group of politicians who, under any other circumstances would likely have been loyal Tories, but for whom the excesses of Eldon’s government were simply intolerable. The two most prominent examples of Middle Tories, as they were known, were Sir Arthur Wellesley and Sir Robert Peel. The former had resigned his army commission and run for office following the death of his brother, Lord Wellesley. A conservative by inclination, Arthur nevertheless found himself at odds with the High Tories on the question of Catholicism. Emancipation had been his brother’s main focus at the time of his murder, and Arthur felt compelled to pursue the same cause, even if it meant alignment with the Canningites.

Peel, for his part, was disturbed by the changes in the British police under Lord Sidmouth’s stewardship. Peel felt strongly that effective and ethical law enforcement depended on mutual trust between the government and the public, and so took issue with the Six Acts, as well as Sidmouth’s use of plainclothes officers and suspension of habeas corpus. Like Wellesley, his main political ally, he found himself in an alliance of convenience with the Canning faction, begrudgingly backing Emancipation in exchange for the post of Home Secretary should the Canningites form a government.

Of course, the Middle Tories’ begrudging concessions towards Emancipation would not have occurred had the grassroots movement in Ireland not gained the strength that it did in the 1820’s. Daniel O’Connor’s Catholic Association upended the status quo in British politics through its mass-based membership strategy. By charging one penny a month, the Association was able to attract a devoted following among poorer Irishmen, providing a foundation for O’Connell’s reformist campaigns. Conservatives like Wellesley and Peel supported Emancipation in no small part in the hopes of preventing even more radical upheavals in Ireland in the future.

An American poster depicting O'Connell as "The Champion of Liberty."

Opposition to the Eldon government also extended outside of political circles, into the economic and artistic spheres as well. In the former, economist David Ricardo was an outspoken critic of the Corn Law. His theories of comparative advantage made the case that tariffs were inherently inefficient, and merely reinforced the tendency of the rentier class to capture profits incommensurate to their productivity. Ricardo died in 1824, but his children Osman and David carried on his legacy, with both eventually standing for office as Whigs.

Even in literary circles, the High Tories found staunch opposition to their regime. Lord Byron, the one-time apologist for the Luddites, proved a thorn in their side from within the House of Lords, skewering the government with his characteristic laconic wit. His fellow poet Percy Shelley was equally acerbic, mocking Lord Eldon as an insincere hypocrite, dismissing his remarks about widows and orphans as “the tears of a crocodile.” [5]

Despite these voices of protest, the unraveling of the Triumvirate came from within. No one member of the trio could keep the government in working order without both of the other men’s skills. This fact mitigated infighting between the three, but it also meant that the removal of one would leave the entire structure unstable. The death of Spencer Perceval in 1827 weakened the government’s grip on its backbenches. Without Perceval to keep them in line, some MPs began to defect to the Canningites, concerned by the effects of the Corn Law on their constituencies. The Tories could no longer unite effectively behind the protectionist agenda.

These tensions weakened the Tories electorally. When the country went to the polls again in 1828, they found themselves assailed by both the Canningites and the Whigs, and their majority suffered as a result, dropping from over a hundred to under sixty seats. Eldon was still able to form a government afterward, but he was forced to rescind plans for additional farm tariffs to forestall a backbench revolt. To make matters worse, Daniel O’Connell had won a seat in the Commons, which he could not fill due to his refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy, further exacerbating unrest in Ireland. Despite the Triumvirate’s best efforts, change was coming to Britain. The coming decade would prove a decisive one for the political development of the United Kingdom.

[1] This is a paraphrase of an OTL quote from Eldon.

[2] This is also OTL. Kinneir examined potential invasion routes to India from the perspective of several potential enemies, attributing some as likely choices for ‘a Napoleon’ and others as better bets for Russia. He was pretty skeptical about most possible invasion strategies.

[3] Obliterationism is essentially TTL’s equivalent to totalitarianism. The idea is that these kinds of ideologies obliterate the individual and their identity.

[4] The Six Acts are OTL, but at least two of them lapsed within a few years. Sidmouth ITTL doesn’t want to let any of them go if he can help it.

[5] Shelley was also quite critical of Lord Eldon IOTL, and naturally has a lot more reason to be here.

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Triumvirate

Excerpted from The Age of Revolutions by A.F. Stoddard, 2006.

If the Canning Ministry, with its tentative and haphazard stabs at social reform, represented listlessness in post-Madrid Britain, then the counter-revolutionary tenor of Lord Eldon’s government marked the first effort by London to take stock of the post-Napoleonic world. For the most part, this meant increased repression of dissent at home, combined with measured isolation from the outside world, and an aversion to high-stakes foreign entanglements.

Eldon’s foreign policy may seem puzzling on initial inspection. Certainly, he had supported the war against Napoleon with all due zeal, so his moves towards reconciliation with the Emperor while in office present a paradox. There are two main reasons for the Prime Minister’s caution. First, he felt that Britain was ill-prepared for another conflict, burdened as it still was by war debts, industrial discontent, and a sluggish economic recovery.

“Men delude themselves by supposing that war contains only a proclamation, a battle, a victory, and a triumph,” he wrote. “Of the soldiers’ widows and the soldiers’ orphans, after the husbands and fathers are buried, the survivors know nothing.” [1]

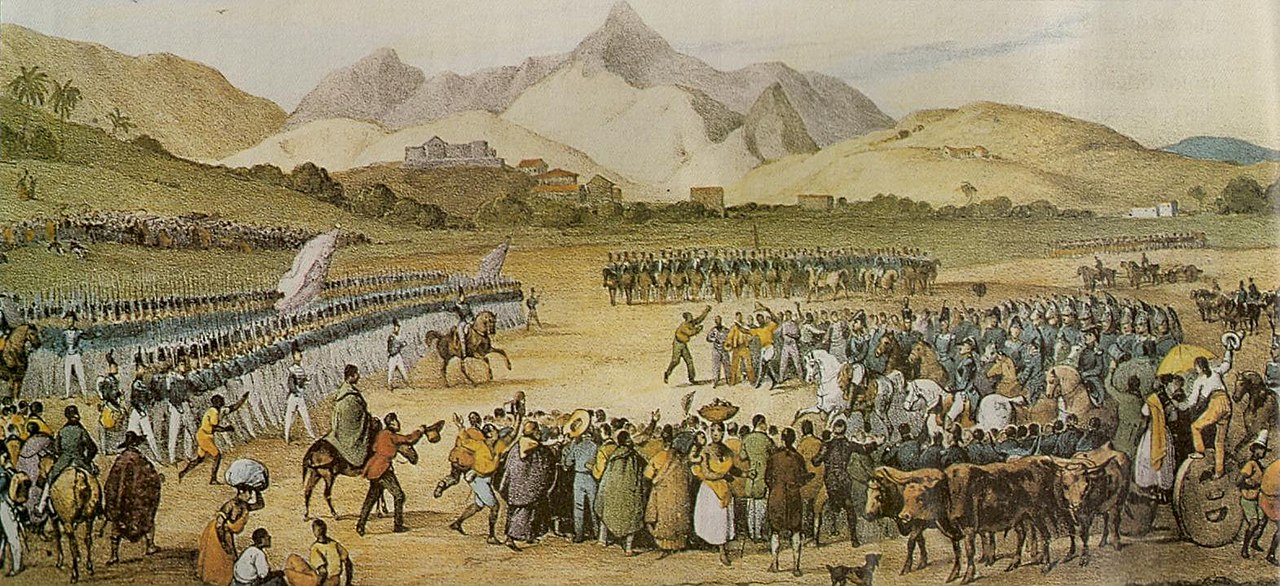

Perhaps more importantly, Eldon and his allies saw the foreign stage from a different perspective than Canning or Castlereagh had. The balance of power on the Continent had decisively shifted in France’s favor, and the High Tories saw few prospects of changing that in the foreseeable future. With that painful truth in mind, they instead prioritized ideological threats. To them, revolution was a contagion, as evidenced by the spread of republican fervor from America to France, and from there to the Netherlands, to Poland, to Latin America, to Spain, and to Greece. And with the example of Arthur Thistlewood, they couldn’t dismiss the possibility that Britain was equally vulnerable.

Because of this, the Eldon Ministry cooperated with France and Austria in an effort to counteract revolutionary movements on the Continent. The primary success from this alignment was the restoration of the Bourbons to Spain. These efforts bore a heavy cost, however; with London unwilling to check him, the Emperor strengthened his hand in the Mediterranean through the 1820’s, while also installing a Francophilic monarch on the throne in Madrid.

This tradeoff was a calculated risk on Eldon’s part. A painstaking study conducted by Sir John Kinneir examined the threat France posed to British India, concluding that the Persian Gulf would be a poor staging ground for such an offensive. [2] Because of this, the Eldon government felt safe allowing French maneuvering in the Mediterranean, confident that it posed little threat to their interests. And the more Napoleon was steered into suppressing revolutionary movements, the less credibility the Emperor would enjoy among liberal circles across the Continent. French self-interest could thus be used to box them into a more conservative role in European politics.

Domestically, many historians have drawn comparisons between the rise of the High Tories and the Second Terror that engulfed France half a century later. In both cases, movements for social change and the disappointment of a failed war led to widespread unrest, culminating in acts of shocking political violence. After that, a reactionary backlash ensued, with a pliant press and public empowering the national government to purge society of its cancers, with horrific results.

To be sure, Lord Eldon and his allies lacked the mad ambition and obliterationary zeal of the clique that governed the late French Empire. [3] As a result, the crackdown in 1820’s Britain was far more tempered. Nevertheless, a crackdown it was, with the remnants of the Spenceans and the Luddites either executed, exiled to Australia, or forced deep underground. In addition, Sidmouth’s Six Acts banned events that offered weapons training without government sanction, limited bail for defendants, and gave local authorities the power to search and seize weapons, as well as disperse public meetings concerned with either church or state. Despite several of these laws including sunset provisions, the government made sure to renew all six statutes whenever they came close to expiring. [4]

Despite this repression of violent agitators, political opposition and dissent was still permitted, in several different forms. In Parliament, the opposition was comprised of three main factions. The first of these were the Whigs, who had finally ousted George Ponsonby after their disastrous performance in 1820. His replacement, Charles Grey, proved a more vigorous critic of the ruling government, castigating Viscount Sidmouth and Spencer Perceval for sabotaging Canning’s Emancipation initiative and “slighting the memory of the former Minister, angling for power before his body was even cold.”

Charles Grey provided the most vigorous leadership the Whigs had seen since the death of Charles James Fox.

For their part, Canning’s surviving supporters also opposed the High Tories. Their program was less ambitious than Grey’s, but they also supported Emancipation. As well, the Canningite Tories, now led by Lord Melbourne, called for repeal of the Corn Law, arguing that an end to trade barriers would enable British goods to contest the French in the European market.

Lastly, there was a small group of politicians who, under any other circumstances would likely have been loyal Tories, but for whom the excesses of Eldon’s government were simply intolerable. The two most prominent examples of Middle Tories, as they were known, were Sir Arthur Wellesley and Sir Robert Peel. The former had resigned his army commission and run for office following the death of his brother, Lord Wellesley. A conservative by inclination, Arthur nevertheless found himself at odds with the High Tories on the question of Catholicism. Emancipation had been his brother’s main focus at the time of his murder, and Arthur felt compelled to pursue the same cause, even if it meant alignment with the Canningites.

Peel, for his part, was disturbed by the changes in the British police under Lord Sidmouth’s stewardship. Peel felt strongly that effective and ethical law enforcement depended on mutual trust between the government and the public, and so took issue with the Six Acts, as well as Sidmouth’s use of plainclothes officers and suspension of habeas corpus. Like Wellesley, his main political ally, he found himself in an alliance of convenience with the Canning faction, begrudgingly backing Emancipation in exchange for the post of Home Secretary should the Canningites form a government.

Of course, the Middle Tories’ begrudging concessions towards Emancipation would not have occurred had the grassroots movement in Ireland not gained the strength that it did in the 1820’s. Daniel O’Connor’s Catholic Association upended the status quo in British politics through its mass-based membership strategy. By charging one penny a month, the Association was able to attract a devoted following among poorer Irishmen, providing a foundation for O’Connell’s reformist campaigns. Conservatives like Wellesley and Peel supported Emancipation in no small part in the hopes of preventing even more radical upheavals in Ireland in the future.

An American poster depicting O'Connell as "The Champion of Liberty."

Opposition to the Eldon government also extended outside of political circles, into the economic and artistic spheres as well. In the former, economist David Ricardo was an outspoken critic of the Corn Law. His theories of comparative advantage made the case that tariffs were inherently inefficient, and merely reinforced the tendency of the rentier class to capture profits incommensurate to their productivity. Ricardo died in 1824, but his children Osman and David carried on his legacy, with both eventually standing for office as Whigs.

Even in literary circles, the High Tories found staunch opposition to their regime. Lord Byron, the one-time apologist for the Luddites, proved a thorn in their side from within the House of Lords, skewering the government with his characteristic laconic wit. His fellow poet Percy Shelley was equally acerbic, mocking Lord Eldon as an insincere hypocrite, dismissing his remarks about widows and orphans as “the tears of a crocodile.” [5]

Despite these voices of protest, the unraveling of the Triumvirate came from within. No one member of the trio could keep the government in working order without both of the other men’s skills. This fact mitigated infighting between the three, but it also meant that the removal of one would leave the entire structure unstable. The death of Spencer Perceval in 1827 weakened the government’s grip on its backbenches. Without Perceval to keep them in line, some MPs began to defect to the Canningites, concerned by the effects of the Corn Law on their constituencies. The Tories could no longer unite effectively behind the protectionist agenda.

These tensions weakened the Tories electorally. When the country went to the polls again in 1828, they found themselves assailed by both the Canningites and the Whigs, and their majority suffered as a result, dropping from over a hundred to under sixty seats. Eldon was still able to form a government afterward, but he was forced to rescind plans for additional farm tariffs to forestall a backbench revolt. To make matters worse, Daniel O’Connell had won a seat in the Commons, which he could not fill due to his refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy, further exacerbating unrest in Ireland. Despite the Triumvirate’s best efforts, change was coming to Britain. The coming decade would prove a decisive one for the political development of the United Kingdom.

[1] This is a paraphrase of an OTL quote from Eldon.

[2] This is also OTL. Kinneir examined potential invasion routes to India from the perspective of several potential enemies, attributing some as likely choices for ‘a Napoleon’ and others as better bets for Russia. He was pretty skeptical about most possible invasion strategies.

[3] Obliterationism is essentially TTL’s equivalent to totalitarianism. The idea is that these kinds of ideologies obliterate the individual and their identity.

[4] The Six Acts are OTL, but at least two of them lapsed within a few years. Sidmouth ITTL doesn’t want to let any of them go if he can help it.

[5] Shelley was also quite critical of Lord Eldon IOTL, and naturally has a lot more reason to be here.