Dentatus brought not only peace to the empire, but also a renewed spirit of cooperation between the Senate and the Emperor. But while the Toltecs held to a "steady" line, a threat loomed from the Old World.

Born into a wealthy family, Lucius Valerius Messalus was the eventual choice of the Senate through its agreement with Dentatus, whom earlier senators offered the titles and powers of a first citizen in exchange for not naming his own heir. Valerius was a man in his forties when the Senate elected him emperor. In many ways, he was of the opposite mind as the power-hungry Nero- the emperor who had gone to war against the Senate - since Valerius was a man with a philosophical distaste for war, taken from his time studying rhetoric and moral philosophy in Civis Mohawk (Philadelphia). His temperament and fondness for the painted arts also earned him the nickname of Flos, or "the Flower". Originally, his opponents in the Senate called him the flower as derision of his lack of male virtues but Valerius and his supporters took the name in stride as emphasizing his status as a peacetime leader. In this way, Valerius promised the people of Elysium another Pax Elysean as an end to the last few centuries of consistent war.

Ultimately, Valerius would become the longest-lived emperor in Elysean history. Coming to power after finishing his consulship in sui anno, he went on to govern the empire for 51 years, exceeding the length of the reigns of either Fabius, and living longer than any emperor before him. Despite his prosperous early reign, Valerius is also remembered for being almost vegetative during the last ten years, allowing the Senate to more firmly reassert its de facto authority. The result would be a weakening of the harmonizing effect of the princeps civitatis and a re-emergence of the factional politics that dominated the Old Republic.

Perhaps the most frightening series of events starting during the reign of Valerius was the surge of the Vikings. What they were threatened and offended by the repeated destruction of their villages on the Scandinavian coastline during the early years of Elysium during the colonial period. Persistent incursions of the Roman fleet into their lands spurred a hatred for the "men beyond the sea" and provided a common cause for the small kingdoms of the great white north.

At this time, the northmen were facing shortages of food and farmland, exacerbated by a massive overpopulation. For that the Boreanari went forth during these tumultuous times to colonize more lands like Gaul Britannia, Frigerra (Iceland), Septentriones (Greenland) and more late raid the legendary lands of the Romans.

The first such group landed in 998 AD in the province Hibernia Superior. Along the coast, the northmen found a small Elysean villa owned by a wealthy patrician of the nearby Civis. His entire family and all his slaves were put to the sword, his wife and daughters left in a manner that suggested rape to the merchant who stumbled upon the remains of the man and his family villa. Everything of value was taken and his private granaries were emptied down to the last grain. The northern raiders must have been amazed that settlements from "Vinland" how they call him were both undefended and wealthy, since they spread tales of the vulnerability and extravagance of the people beyond the sea when they returned to their homes in Scandinavia. Many people in that land would have known about Romans and their cities but the success of this raid seems to have put this knowledge into a new light for some Scandinavians, slowly encouraging future attacks on Elysean soil.

News spread quickly throughout the empire of how brutal pirates raided the home of an aristocratic citizen. Since none of the family was spared, Elysean came to the conclusion that the northmen were so savage that they were even deaf to cries of being a Elysean citizen (people of Elysium believed that the claim "

Civis Elysium sum" or "

I am a Elysean citizen" would force clemency from foreign attackers). However, the news aged by the end of the year, as most news of isolated events did in the face of gladiatorial games and imperial propaganda. When several small villages were similarly sacked from 999 AD to 1000 AD, the majority of the empire was no more alarmed. Unbeknownst to the Senate, these raids were increasing in frequency and intensity as more northmen participated in these raids.

The Vikings had united themselves behind Erik Thorvaldsson known as

Erik the Red. Rhetoric to his people spoke of pay the Weregild after the enslavement of thousends of Northeners during the Roman Empire. In January of 1005 AD, he rallied his entire army behind another raid, promising them a great "harvest" to get them through the Winter. More than 10,000 Vikings crossed the sea between Greenland and Elysium and began laying waste to the countryside. Thousands of farms were raided for their winter stores and thrice as many Elysean citizens were put down by axe or sword or even enslave being target for brutals treatments.

With characteristic reflexes, the three legions posted in the province chased after these northmen. However, intel on the enemy was scarce and the same strategies used to fight earlier small raids were used against this invasion. Once several cohortes worth of men were lost after getting ambushed by larger than expected numbers, the legate of the province changed strategies. However, his reaction was too slow and the raiders had left as the season passed. Requests were sent by this legate directly to the emperor, asking permission to lead four legions into Greenland. His request was denied due to the risk and the cost, and instead the man was dismissed for his failure to defend his assigned province. At the same time, the emperor appointed a new legate and relocated two legions to assist in the defense.

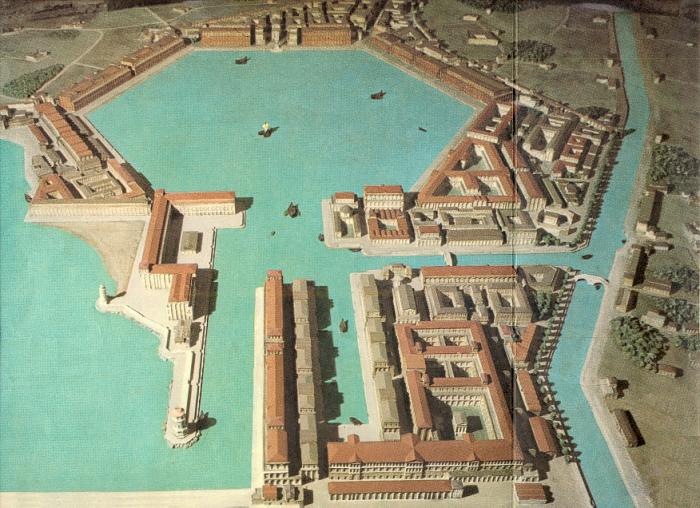

Next Winter, the Vikings returned in greater numbers. Instead of raiding along the coast, Erik sailed unimpeded and reached the urbs of Civis Terranova in the island of the same name. This city of 100,000 citizens was defended only by a hundreds or so town guards, since the legions were focused on patrolling the coastline. As might be expected from a fleet of 20,000 raiders, they sacked the city. The granaries of Civis Terranova were emptied and most of the once great coast city was burned to the ground, leaving only a skeleton of marble buildings and stone walls.

The sack of Civis Terranova convinced the emperor that defending Elysium from raiders across the sea was impossible, even for the Legion. Dominarch Terentius was recalled from the Western provinces, where he was charged with supervising the defenses of the Limes Toltec, for deployment at the head of an army to invade the Viking territory.

During the Invasion of Septentriones (Greenland), the Elyseans learned to communicate with the Boreanari because Latin continued to be a Linga Franca in Europe (albeit with different dialects and time variations) and thus made it easier to communicate. The Roman expedition took no risks. The gunners were kept on constant alert throughout the day. Large camps were prepared before each night, and efforts were made to end each day with the sea to one side of the camps (protected as the coast was by a continuous cycle of decaremes and quinqueremes). Slowly, the legions razed the coastal towns and the houses of the lords who lived a few kilometers inland. Almost 500 km of coastline were devastated over three months, including the village of Erik The Red. In the end, the invasion was a massacre of the Vikings, crippling their ability to further damage Elysium, and Septentriones returned to a dead land.

Erik the Red died during one of the battles and would go down in legend in Viking history. His son would formally make peace with the Senate. Unfortunately, royal authority was weakening in the wake of this effective genocide of the Boreanari, and other Norsemen were beginning to take advantage of their weakness. The Nordic survivors ended up as slaves who at the same time provided further information from Europe to Elysium. The Panorama of Christian supremacism did nothing but make them look like the last bastion of Rome, even if Constantinople had achieved greater power in the East.

During the

Boreani Bellum, Valerius lamented the weakness of Elysean naval power and the manner in which it had been waning ever since the last reform the Classis (Fleet). Emperors were barely restoring or trying to replace ships, leaving the entire fleet in a dreadful state of disrepair. This other emperor's attempt to bring glory to the fleet of his empire was hampered by insufficient funds, and disinterest from his successors in the maintenance of his expended fleets. Nevertheless, the command hierarchy instituted remained in place.

Valerius spared no expense in his total renovation of the Classis. In order to ensure that his reforms stuck, he transferred total control over the fleets of the empire to the Senate. Past emperors feared giving military power to the assembly of aristocrats but a navy could not be used to overthrow an emperor and the time had long passed when revoking the autocratic office of princeps civitatis was realistically possible. Control over the Fleet was given to the Senate through their power to elect and dismiss the five procuratores navales who commanded the high fleets (greces). Their leader, the Procurator Admirabillis, would possess magisterial power to authorize funds for the navy, up to a limit of 150 million Dn, unless opposed by the Senate. Of course, in placing control of the navy out of the hands of his office, Valerius made sure to force the Senate to elect him as the first Admirabillis for the remainder of his reign.

Redistributing authority over the sea was far from the only reform enacted by Valerius. With his position as Admirabillis, the emperor pursued the task of modernizing and expanding the high fleets of his empire. Each body of water faced different types of threats and Valerius knew enough about naval warfare to design appropriate fleets for each region when he began proper renovations of the Classis. Before outlining ship distributions, a major change in ship design should be mentioned. The liburna (fast bireme) had been the mainstay of the Roman Fleet, as a fast and maneuverable vessel. Valerius had shipwrights replaces the classic ram with a light wooden spur and change from single-masted square sails to triple-masted lateen sails which were capable of tacking against the wind by beating out a zig-zag trajectory. This new ship design relied on a similar hull and deck to the liburnian galley but received its own name from the emperor - the cursoris (runner).

[a cursoris effectively looks like a triple-masted dromon with more oars, as a bireme-style galley]

For the Altantic, Valerius commissioned over two hundred cursores and four deceres (decaremes) to be split between the Grecis Superior and the Grecis Inferior. Vessels would continue to be assigned a military officer (decurio classiarius) who commanded a small division of marines, usually Elysean citizens but not paid or armed to the same degree as legionaries. Remiges (rowers) would be peregrini hired from coastal towns, supervised by a rower who had risen to the rank of celeusta for the ship. Rowers were lightly armed to help repel boarding parties.

Every ship regardless of class was under the command of its navarchus (captain) and piloted by its gubernator (helmsman). Squadrons of ships would follow a captain of higher rank, known as the navarchus princeps, and were the next smallest group below a classis (Navy). The Legatus classiarius (commander) of a fleet was filled by navarchi who rose through the ranks but the Procurator Navalis who acted as their commanding officers were patrician magistrates appointed by the Senate. Since there were few legions stationed along the coast, the two internal high fleets had little interaction with the Legion, relying on their marines for the occasional battles with pirates.

Seas and rivers connected to the Oceanus Atlanticus were within the jurisdiction of the Grecis Atlanticus. Among its duties was the patrol of rivers was only recently starting to realize the importance of another job.

Nearly a hundred runners were built from Navaliae (shipyards) in Appalachia Inferior and Nova Liguria. These would be concentrated in the Oceanus Atlanticus Superior (North Sea), where they could continue to pursue potential invaders. As part of Valerius's reforms, the greatest warships of the fleet became the deceres ("tens"), floating fortresses that could perform the role of an inviolable platform for archers and artillery. These were slow ships but they were armored where necessary and armed to the teeth with the latest artillery.

Despite his distaste for warfare, Valerius saw the need for Elysium to defend herself against those who sought her wealth and power; this emperor was not too naive to shy away from strengthening the martial and naval forces of his empire. He left the logistics of the Legion in the hands of a capable Dominarch (most general commander of the armies) but took it upon himself to improve its capabilities through military research. No emperor before Valerius gave as much funding to the Technaeum Armarum et Armatura (Technical School for Arms and Armor), as he often devoted more than 60 million Dn to this venerable public institution. With the patronage of the stage, the Technaeum could triple its staff and double its student body within less than a decade, bolstering its number of doctores ballistarii (artillery technical instructors) with graduates who did not join the Legion.

The quality of instructors during this period surpassed earlier times and would not again be matched for centuries but only one of these men is worthy of extended consideration. This notable doctor ballistarius was the son of an instructor who starting working at the Technaeum around 1740. Little is known with certainty about the boy's early life while his father taught at the school but it seems certain this man had taken his child to work after his wife died. The young Gaius Pistorius Mica is supposed to have spent his time in the libraries, teaching himself from books.

Mica properly entered the historical record upon enrollment at the Technaeum in 1755 as a student. Already familiar with the lessons, he spent much of his student life conversing with his father's colleagues and watching tests for new artillery pieces. At this time, some of these instructors were hiring him to produce copies of their designs for distribution to the Dominarch and other military officials who might be interested in their weapons. Drawing copies was a common task delegated to students but professors favored Mica for this job due to his growing reputation for fastidiousness and for catching problems in the original designs. Although this young boy had no artistic talent, technical drawings at the time were largely geometric. Nevertheless, one of his instructors paid for his training under a famous local artist, who history forgets, so that Mica might produce drawings with aesthetic appeal to match his precision.

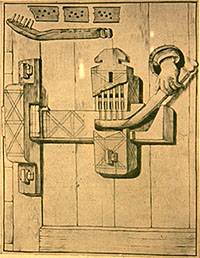

Mica's attention to detail and systematic approach to drawing helped him train quickly as an artist. When he graduated from the school, Mica had developed exceptional artistic skills, that would only improve throughout his life, and professors were fighting to have him partnered with them instead of with their colleagues. The practice for graduating students staying as doctores was to be made an apprentice of sorts with senior professors, assisting them with research and teaching before working independently. By this time, Mica had suggested changes to the carroballista, noting that its collapsible wooden shell could be replaced with a collapsible wooden skeleton holding up leather sheets, if the skeleton were properly designed (something he supplied), and had been one of the minds behind a simple cranequin for reloading a crossbow by cranking a gear that pulls a rack to draw the string.

In strong hands, the original polytrahos could be unloaded within 15 seconds, as demonstrated to the group that assembled one afternoon in the training field of the Academia Bellica (War Academy). Onlookers were astouned by the performance of the weapon. The mechanism of the device differed heavily from the polybolos - the common semi-automatic artillery piece used by legionaries - and was less than half its size, aweing even the most expert observers that afternoon. Within a few weeks, Mica was called to Augusta Elysium to personally receive an offer of patronage from the emperor, who had heard everything about the young man. The emperor's gift was a large property close to the Technaeum that would serve as Mica's private workshop.

As a condition of his patronage, the emperor tasked Mica with improving his design of the polytrahos for widespread applications. As unique as its function was, the original polytrahos demonstrated in the training field was completely impractical. First, there was no way to reload the weapon without removing the magazine, which had been nailed and sealed to the stock. Second, its power did not match other crossbows of similar size and weight, although it could still penetrate leather plates and ringmail. Third, firing from the knee would work on the field but was less useful on the battlements of a wall, requiring other ways to deploy the polytrahos. Over the next decade, Mica devoted a great deal of his time toward improving the weapon that made him famous. Otherwise, Mica was free to pursue whatever work he pleased. Granting the brilliant inventor this liberty would not go unrewarded:

During six years, Mica produced few devices of note as he spent most of his time either working on the polytrahos or building little mechanisms just to test an idea or see where an thought led - a formative process in his understanding of machinery. One device that he asked to be shown to the emperor was a portable bridge which curled into itself for convenient transport on a cart drawn alongside a legion. His final design unfurled to ~4.73 m (16 Roman ft) and curled into a cylinder only one and half meters in diameter. Rolled into an octagonal cylinder, it was 1.48 m tall, meaning the unfurled bridge would be that many meters wide. This was wide enough for two legionaries to march concurrently in formation over the bridge. To support the weight of soldiers and wagons, the bridge had removable metal poles that could be threaded through its edges along the entire length. Valerius demanded that cohortes going beyond the national frontiers each have one bridge, removing the obstacle of small rivers for the Legion and its supply line.

In early 1768 , Mica unveiled designs for a small assault boat created to ram enemy ships - naming the vessel a vespa (wasp) for its particularly potent sting. A single vespa was driven by two paddlewheels each operated by one man, using mechanical advantage to increase the speed of his paddling tenfold. The prow was covered by an armored shield, thick enough to shrug off projectiles as large as those of a small mangonel. This shield extended more than halfway back and terminated in a solid metal horn. Once a vespa rammed the enemy, its shield would open to expose a miniature siphon (pressurized hose) for spewing Athenian fire (Greek Fire). There was enough of this flammable and waterproof fluid for a short spray that could rapidly engulf a ship in flames ignited from within the bowels of the ship (through the hole made by ramming). Overall, vespae were designed as small and light craft, that could pierce a hull with only their speed and sharp ram - more importantly, the vespa was a low-cost way to deploy Athenian fire, allowing only two men to destroy an entire enemy ship without help.

An undeniable cleverness could be seen in the design of the vespa, helping Mica's national reputation grow. The two pilots of a vespa guided themselves by the aid of a polished bronze mirror that doubled as protection for the stubby mast, but the vespa was intended to be aimed at its target before bringing the vessel up to speed. The shield opened rapidly after pulling its brake - fast enough not to give time for defenders on the deck above to kill the pilots before they could light the primer and fire the weapon. By design, a vespa was meant to be deployed alongside two false craft without the fire projector. When the vespa had proven itself as a reliable weapon, there came to be one vespa on every decareme in the fleet.

Working for another two years on Athenian fire, Mica created a ballista for launching lit containers of Athenian fire instead of stones. Ammunition had to be lit in the moments before firing. Although the flame ballista had the advantage of range over the siphones that normally deployed the fire, it lacked the intensity of a continuous stream of flame and required additional caution to light a fuse that burned strongly enough not to fizzle midflight but not enough to burn the cords of the bow. For this reason, the siphon remained the more common means of using Athenian fire, with only moderate and judicious use of these fire spitters.

Working to improve upon the techniques of ironsmiths, Mica developed his own process for smelting iron, one that resulted in a far more durable and malleable alloy than wrought iron. From a chemical perspective, the alloy was a high carbon steel forged from wrought iron using high-temperature crucibles. Although similar to the famous norica (noric steel), the new alloy could be smelted from any ores of iron, as opposed to only the local ores of the province of Noricum. In addition to widespread availability, Pistorian steel (norica pistoriana) surpassed traditional noric steel in durability and the potential sharpness of its forging.

These advantages cannot be overstated. Noric steel was in extremely limited supply throughout the history of the empire but this steel could be forged from any source of iron, once a proper crucible forge was prepared. Greater durability has obvious utility in sturdier weapons and more robust armor but the malleability of the material - allowing its folding into sharp blades - also ensured aptitude as a material for springs. In particular, Mica recognized the potential of Pistorian steel as the armors or more.

His earliest application of steel in ranged was a solid metal tube could effectively concentrate the force of gunpowder into one single stream. Optimal designs for concentration were tried, but a simple thin, bell-like shape always proved to be the most effective. Although this invention was mostly used for spectacles, or in attempts to use it as a pump, in Mica discover a way that the force could be used to fire a projectile. This had of course been considered several years earlier, but the projectiles largely ineffective to fire from the tubes. This time, the scientist used round balls of metal as the ammunition. A weapon of this kind was about 3 meters in length and 50 kg spherical shell a distance of about 100 meters. No structure built by any of the Elysium's neighbors had the capability to resist this weapon. The palisades were shattered, creating holes almost half a meter across at every hit, and troop formations were scattered by the force of the weapon. With the first prototype constructed and fired in 1766 AUC, the Age of the Cannon began.

Immediately, the Caesar was informed of the invention so that production could be started on the advanced new weapon. Though by 1770 only 30 Calanum (cannon) had been built, methods of production as well as places of production were rising in importance and their production was about to see a large increase. Still, in the mean time, the Elysean army was preparing for these additions to be made to their army. A new artillery training was created to service and fire the weapons, with about 6 men needed per cannon, particularly as they were difficult to move. However, the effectiveness of the weapon in war was yet to be demonstrated.

Drawings for this latest machine were sent to the emperor - delivered under the less than modest title of Testuda Invicta (the unconquerable tortoise) . Like many of Mica's weapons, its design was inspired by nature - this time by the eponymous tortoise.

[a Testuda Invicta looks like the Leonardo da Vinci's fighting vehicle but with one cannon a turret for Polybolos]

Enveloping a Calanum in a conical steel shell, Mica created a moving, armored artillery piece that could move forward into battle under its own mechanical power. Five men were sheltered inside the shell. When in motion, each man served his turn as its pilot, watching through thin glass slits and directing the actions of his companions. Meanwhile, these other men worked in pairs on either the left or the right set of wheels, pedaling forward or backward at different rates according to instructions from the pilot. Using the mechanical advantage of gears, these legionaries could propel their testuda at the pace of marching troops, likely exhausting them after less than a half hour of travel. For this reason, the testuda was designed with the advice that a testuda be pulled by mule when not in battle, allowing the pilots to ride within and stay rested for the physical intensity of combat.

A testuda left little room within its body for occupants. The middle plane of the cone was dominated by the Calanum, extending almost the full diameter of the shell and only able to angle itself vertically. Just above the main weapon were two polybolos for fight against fast targets. Most of each turret lay safely within the testuda shell, swiveling freely about where their long snouts - that extended several inches ahead of their respective arcs - attached firmly to the vehicle wall. When a stationary position was taken during a battle, two of the pilots manned these polybolos. The last man both fired and reloaded the Calanum, assisted only in the latter task by the two ammo feeders (leaving him to crank its winch himself).

Before a battle, other legionaries would run the pedals for as much time as they had in order to charge the flywheel for each pair of wheels. This storage device had been designed a decade and half earlier by Mica, requiring a few modifications to avoid losing most of its energy to the sudden bumps and shocks that were inevitable when riding inside a testuda. Enough energy was stored on a full charge of the flywheels to ease the legwork of the men driving the machine but not enough to propel the machine on their own. Each flywheel consisted of two 12 kg steel balls on opposite ends of a 0.42 m steel bar rotating about its center, sitting at the same height as the wheels and able to drive its respective wheels whenever a pilot engages a small lever in the cabin. The property of the flywheel that made its use here possible was a mechanism for slowly bleeding off stored energy to the wheels.

Tactics for using a testuda in a siege and in open battle were detailed in a short booklet that Mica included with his designs. A testuda needed decent infantry support on a field but returned the favor with its devastating effectiveness against cavalry and its invulnerability to archers. With the polybolos, massed infantry were also quite vulnerable to a testuda, although they could disable one once close enough and a limited ammo capacity restricted a testuda to only 5000 bolts from its polybolos and 20 Balls from its plumballista. However, Mica noted the potential to crush enemy morale with the sight of a seemingly invulnerable machine that would be killing almost one man every second for the first quarter of an hour of battle - also mentioning the bonus to the morale of one's own troops by fighting alongside such a monstrosity.

On open field, the conical shell of a testuda towered almost eight feet above a legionary. Its bulge at the widest point extended out far enough to allow two men to lie down inside its belly and fully extend their arms and legs (nearly 16 feet wide). For armor, a testuda had almost five tonnes of Pistorian steel wrapped around its cone, protecting its occupants with an inch thick wall. The wooden frame added another two tonnes, for a total of nine tonnes when full of ammunition and men. Every attempt was made by Mica to conserve weight, since the men inside needed to move everything by their own strength.

Mica boasted that a testuda was the only siege engine that a legion would ever need. No wall, or at least no gate, could stand against its powerful Calanum and an army would feel half its actual size in the face of its turrets. Nevertheless, he advised the emperor to provide one to every cohort - ten for each legion - so that the armies of Elysium might be invincible. Instead, he heard that only one would be made in Civis Lenape, under his own supervision, before the decision for mass production would be made. The emperor was less enthused by Mica than Valerius but he would not miss an opportunity such as was being offered.

As Mica entered his twilight years, his prolific mind did not slow, although the ambition of his projects was tempered. Five years before he delivered the plans for the testuda, Mica sent the emperor his final designs for the polytrahos. Since the first repeating crossbows had been made, the auxiliaries of Neronia had been equipped with them. Without a doubt, the simple to use but effective weapon was suited to the amateur troops who guarded the borders and towns of the province. Criminals were loathe to confront a town guard when he could easily loose enough arrows to turn him into a pincushion before he drew a blade. For its success, the polytrahos had become the standard armament for auxiliaries by 1780.

In particular, the polytrahos is now seen as the weapon that tamed the Wild West. They were sold freely only in the Limites territories, where merchants and homestead owners could use them to defend themselves against the wild men who descended from the original residents of the land. Suddenly, one Elysium Citzen could hold off an entire band of men, even from his horse, where before only a large trade caravan could bring along a polybolos cart to protect its goods while citizens living on farms could only rely on a polybolos wherever they stationed one as a turret, giving raiders the opportunity to avoid their primary means of defense.

For town guards, Mica designed a saddle-mounted polytrahos that restricted the horse to a slow trot but turned the rider into a formidable keeper of the peace. Sitting with his weapon in front, these auxiliaries could patrol at leisure without worrying about having to pull their weapon off their back at the first sign of trouble. Sending even one guard on horse with a polytrahos would do as much as sending ten archers, vastly improving the efficiency of the auxiliary city guards.

Dozens of other turrets, each of a different size or ammunition capacity, were designed for future needs, as Mica did not trust anyone to accommodate his design to suit a new problem. Few of these would ever see the light of day. However, the most useful of them was a large turret intended to replace the polybolos on the battlements of Elysean walls. A holster for magazines gave one defender the ability to loose nearly five hundred arrows without assistance or preparation, unlike the polybolos which needed one man to crank and another to feed ammunition. This heavy polytrahos would become a reliable ally for auxiliaries on defending the borders of the Elysean Empire, turning a single soldier into an entire battery of archers.

For every siege engine that the emperor accepted from Mica, there were two or even three that were rejected as impractical or even impossible. A long list of these inventions is difficult since there are no single terms for them, obscure as they still are. However, an attempt can be made to describe a few of these strange devices. The majority of them were found in the writings of the great inventor or in the remaining fragments of letters that he sent to Elysium.

Sketches of a diving suit, a diving bell, and other small water craft were sent to the emperor alongside designs for the vespa. Following the lead of Archimedes, he created versatile cranes for lifting ships out of the water during a naval siege as well as a handheld version of the siphon for spraying Athenian fire. There were also sketches of a carriage housing a mobile forge for replacing weapons on the field and of ships filled with Athenian fire that could be ignited in proximity to a formation of ships. Aside from these distinct devices, there were also alternate designs for those war machines that were accepted, where these variations preceded little or great modification before producing the final designs.

First and foremost, Pistorius Mica was a military engineer employed by a national academy to build weapons of war. However, his curiosity and the freedom allowed in his work left him some spare time to pursue non-violent applications of machinery.

Most of his civilian inventions were commissioned by merchants working out of the Grand Harbor of Lenape. A number of them were merely improvements on existing devices. For example, Mica created a water-powered paper mill, improving upon the paper mill invented in Septimia by allowing for the continuous forming of paper sheets using rollers. Machinery for pulp mills, grain mills, stamp mills, and sawmills were invented by Mica, before he left Lenape on a series of trips for the promotion and creation of his testuda. Meanwhile, he also worked with shipwrights in the development of the double hull for ships, although its invention is barely attributable to Mica. The double-layered hull eventually became the standard for all military vessels in the empire and would become a popular design for merchant ships.

His greatest civilian invention during this twenty year period was the windmill, using the windwheel designed several centuries earlier by Hero of Alexandria (10-70 AD). His original windmill had a similar appearance to the waterwheel except wooden panes were replaced with a light fabric on a wooden skeleton and a wooden barrier blocked the wind blowing through one half of the windwheel, replicating the effect of only half-submerging a waterwheel into flowing water.

Several windwheels were put on the roof of the Grand Harbor for powering the cranes used to transport cargo throughout the docks, lightening the load for the person operating each crane. Indeed, the rooftop windwheel would become a popular device for driving low power machines in coastal cities. Due to the axial symmetry of how windwheels were connected to the machines they powered, the "well" in which the windwheel sat on a roof could be rotated to catch a better wind. These rooftop mills did not take long to grow in popularity among artisans, especially in places where water was not as abundant as Neronia.

Windpower may not have been as strong as waterpower could be and energy could not be stored for later use, but it was far more readily accessible given the dwindling amount of accessible water in the empire. In fact, the Elysean Empire was close to reaching its peak capacity for water power in some of its provinces, capping its industrial growth. In Augusta Elysium itself, industries had access to the equivalent of ~1 billion kWh of mechanical energy from its aqueducts, using it to drive watermills for grinding grain, making paper, sawing wood, polishing lenses, and billowing forges within the city. Centuries of integrating machinery and aqueducts into workshops in Augusta Elysium had led to this unprecedented access to non-electrical energy. For this city of 1.3 million, an average citizen had ~769 kWh of energy, but in practice most of this energy went to workshops and the homes of nobles.

Although the rooftop mill would not become popular in Rome itself, the nearby town of Civis Mons Regius (Montreal), benefitted a great deal from its use, nearly doubling its access to energy over the next few decades. Other port towns experienced a similar industrial growth as workshops throughout the Elysium world commissioned their own rooftop mills. Inspired by his windwheels, Mica invented a better anemoscope that indicated wind speed by its rate of rotation. He built several of these anemometers for the Grand Harbor, giving a reliable means of knowing the speed of the wind before setting sail. Other more open air ports were able to more openly display his anemometer to people on the docks.

There is no comparison in any other part of the world for the industrial capacity of the Imperium Elysium during this time. Centuries of peace within its core provinces was the perfect environment to foster the sophisticated application of machinery to the existing infrastructure of aqueducts. An industrial revolution of a sort may be viewed as starting near the end of the 9th century and early 10th century, when urban watermills started to be run off the energy that aqueducts supplied. Concrete dams were built out in the countryside near the starting points of aqueducts to raise their water to higher starting elevations. With this added energy, some energy could be diverted to watermills built along the length of each aqueduct while still leaving energy for the city at its terminus.

By the 10th century, this industrialization had peaked in most Important cities. As much of the water supply was being tapped for power as was sustainable given the myriad other uses of water and its reserves throughout the territory. At this point, Augusta Elysium had daily access to ~50 amphorae (343 gallons) per citizen during the Summer while farmers used a separate supply of water for crop irrigation. Access to waterpower was still growing in the Western provinces, accelerated by immigration and an extensive local network of rivers. Overall, the empire had an industrial output that stood midway between its contemporary civilizations and an industrial civilization, exceeding those neighbors in production by several orders of magnitude.

Fueling these industries was a longstanding tradition, of sustainable forestry. At this time, Hibernias provincias and Appalachia had enough forest coverage to supply all the timber and firewood of the Empire. Sustainable forestry was no more evident anywhere than in Appalachia Inferior where nearly a fifth of its land was devoted to forestry zones, where wood was harvested in the manner of a crop. This access to timber played a major role in the incomparable level of industrialization of Appalachia by the 9th century.

Nearly as important as sustainable forestry was sustainable water. Elysean geologists understood where water came from before being taken by aqueducts and hundreds of geologists were employed throughout the empire to monitor these reserves by measuring the water level of mountain lakes and the flow rate of mountain rivers. Elysean did not understand the mechanisms that sustained these reserves and did not know the source of water from underground wells, preventing them from investigating the water reserves directly in the water table. More importantly, Elysean geologists knew the effect of irrigation on soil degradation and had long been advising the Senate on agrarian laws regulating the proper treatment of soil on the farms of citizens. For this reason, farms remained highly fertile after centuries.

Around the turn of the last century, a weaving machine powered by pedals was introduced. Replacement of older hand looms with this vertical pedal loom was slow but Mica heard about it from colleagues and more later, he improved upon the design by use water-power in place of pedals for operating the heddles. Some weavers in Lenape would further improve upon the water-powered loom by replacing the warp-weighted vertical loom that had been used for centuries with a more convenient horizontal loom.

A guild of weavers in Lenape commissioned Mica to create a device for spinning thread into yarn, freeing laborers for more intricate work. His piece was a spinning wheel that could be powered by either water or a treadle. The former could be powerful enough to produce the high quality yarn required for weaving. This device would be steadily improved by other more devoted craftsman than Mica, until when hand spinning had gone out of practice for Elysean citizens.

Agriculture was an immense industry, where a handful of aristocrats owned massive latifundia (landed estates) where slaves farmed crops for shipping to another provinces. Besides, the lands in Appalachia Inferior were the primary source of food for the empire. Hearing of the prowess of Mica with machines and being dependent for centuries on the mechanical reaper for harvesting crops, some landowners outside Civis Centolacus approached the great inventor to improve the reaper.

Visiting the countryside for a few seasons, Mica asked to go a step further in assisting the estates, compiling an ordered list of steps in the production process of their farms and detailing existing tools and techniques for each stage. Unfortunately, Mica was forced to leave Dacotas for a decade to lobby for his testuda and eventually to supervise its construction in Lenape. Upon his return, he had a number of ideas for the latifundia of the province which he showed his potential patrons.

First, he observed that the difficulties slaves often had in carrying large bags across short distances on the estates wasted their time and made them less productive. For this reason, he advised a re-purposing of the pabillus (one-wheeled cart), used on some construction sites, for carrying large loads over short distances. He designed such a large number of wheelbarrows that he recommended that a latifundium keep dozens of them for different tasks. His efforts to convince landowners that this tool would be profitable were rewarded with the dissemination of wheelbarrows in agriculture.

Second, Mica modified the heavy mouldboard plosw to have a removable board that allowed tillage of soil in one direction for one furrow and the opposite direction for the other furrow. In short, this design permitted continuous plowing of a field, stopping the build-up of soil into ridges that created the characteristic topography of tilled agricultural land. Another facet of his design had the mouldboard covered completely in cast iron. The general concept of this heavy mouldboard iron plow were disseminated through Dacotas farms before reaching widespread national use by the end of the century.

For irrigation, Mica had the estates replace their Archimedes' pumps with a screw pump that he had invented as a tool for rapidly removing water from on board a ship. In principle, this pump consisted of two intermeshing Archimedes' screws enclosed by the same container. However, the screw pump proved more unreliable for work on a farm and was swiftly abandoned in favor of the older Archimedes' screw pumps.

A final suggestion to landowners was a three-field rotation of crops, where only one field would go fallow out of three instead of the common two-field crop rotation where half of the arable land was unused at any given time. His recommendation involved adding a year in the crop cycle where a field would be planted with legumes such as peas or cabbages. Unlike his more mechanically minded ideas, this concept of more elaborate crop rotation was owed to the farmers of Appalachia, from whom Mica learned of the replenishing power of legumes for soil.

After returning to his workshop, Mica retired from the Technaeum and his work for the Legion. Several testudae were already constructed in Lenape and final designs for various types of polytrahoi were in the hands of other artillery engineers. With his rise in free time, Mica devoted himself to implementing ideas that had come to him during his voyages throughout the empire for business. Among these designs, the first that he pursued was a screw press that forced ink into paper, leaving behind the imprint of an image. This image could be a woodcarved drawing or a series of letters arranged into a codex page, permitting the repeated printing of a single page onto multiple sheets of paper. Once metal blocks for letters were cast and arranged, a page could be printed in the seconds that it took to apply ink to the blocks and crank the screw press into the paper.

This design for a printing press was inspired by a visit to the imperial mints in the capital - the sole location permitted to mint coins. Following the operation the punchcutting machines for coins, Mica invented a machine that could punchcut moulds as templates for the casting of metallic types of letters. These dies would get arranged into sentences on a larger plate before being pressed. The first movable type printing press of this sort was used in 1780 to create dozens of copies of the book On Motion by Dionada, requiring about a dozen other assistants to help arrange the movable types. Over the next few years, Mica invented a water-powered printing press that could alternate pressing and releasing with the change of a single gear.

After the Technaeum recruited Pistorian presses to print copies of the Commentarii de Bello Gallico by Julius Caesar (a text that all Elysean officers graduating from the Academia Bellica had to know), Mica accepted the school's request to be named its Scholarch, giving him ample influence to expand the use of his new invention. By 1785, eight printing presses were running at the academy and thousands of copies of the Commentaries had been printed. Thirty years later, there were nearly a thousand printing presses spread throughout the empire, each printing up to 3,000 pages every day. Although printing became just another Elysium industry, this was an industry that would revolutionize the society of Elysium , bringing the written word to the common people.

More than anything else, Mica contributed to the history of science and engineering with his theories and techniques for studying nature. Teaching himself by reading Dionada at a young age, Mica stuck his whole life to the basic principle of Atomism - that every object was composed of indivisibles and the motion of anything could be studied by the linear motion of its atomic parts. With these beliefs, he led a revival of Atomism in the empire, as its ideas permeated all of his writing. No one could read first hand about the discoveries of the great Pistorius Mica without seeing them through the lens of Atomism.

Later in his life, Mica published a treatise that summarized his understanding of mechanics through Atomism, presenting what he termed the First Principles of Motion:

An atom travels straight unless it is acted upon by another atom.

The action of one atom upon another involves no loss of geometric momentum.

From these laws, Mica went on to describe how conata (efforts, or in other words, momentum) was exchanged, expanding the theories of Dionada beyond just collision. His theory is that the actus (action) of one atom upon another is required to change the motus rectus (rectilinear motion) of an atom, as he saw motion in a straight line as the natural state of every atom. There were two types of action in Mica's physics: collision and action at a distance. The latter type of action replaced Aristotle's teleological explanation of gravity and buoyancy using concepts of natural motion and the natural places of the elements. These notions had been on shaky foundations ever since material philosophers such as Balerios added elements to the original five.

Modestly, Mica professed that he could not say how but he could plainly see that some atoms can push or pull other atoms without collision. Action at a distance developed from Dionada's concept of connection, which he described as a tendency for atoms to attract when moved away from their natural arrangements and used to explain gravity and elasticity. The difference between action at a distance and connection was that the former manifested as a change in motion along a line joining the interacting atoms instead of in the direction that brings those atoms back to their "natural arrangement". Indeed, Mica did away with natural arrangements as much as he threw out Aristotle's natural places.

Several observations further developed Mica's concept of action at a distance, especially as it manifested as gravity. First, he pointed out that lighter objects fall no faster than heavier objects. His theory of gravity required that its action on heavy bodies was greater than its action on lighter bodies but he observed that heavier bodies were harder to move by the same proportion so the result was an identical change in motion under gravity for all bodies. Second, he observed that dropping an artillery shell from the mast of ship did not involve the ship leaving the shell behind, as Aristotle believed. Instead, the shell retained the motion of the ship even after no longer being in contact with the ship as it fell. For this reason, Mica believed that a person below deck on a ship, that could sail through the sea without rocking, would be unable to say whether or not the ship was moving, since objects would fall or follow trajectories no differently on a stationary than on a smoothly sailing ship.

Third, he followed Dionada in arguing that the Earth, as the heaviest aggregate of atoms in nature, pulled on the planets and Sun in the same manner that it pulled on ordinary bodies through gravity. His seminal treatise Prima Principia Kineses became the first widely received natural philosophy text to say that motion in the heavens was the result of the force of gravity. Sadly, this hypothesis of universal gravitation would take some time to receive widespread acceptance. The Principia also contained a large number of geometrical problems, for calculating motion under gravity, whose methods for being solved are not far from the method of integration, as they follow the geometrical method of exhaustion pioneered by Archimedes.

Since Mica and his contemporaries regarded the planets and Sun as the lightest of bodies, his argument that the strength of gravity was proportional to the mass of the attracted body could only be applied to the planets under the understanding that lighter bodies were easier to move in proportion to their masses and, therefore, every body responded the same way under gravity. For a system of this form, Mica took up the Dionadan description of orbits as "falling such that the target is always missed".

Fourth, he discovered by careful measurement that a distance fallen by a body was proportional to the square of its time spent falling, by a numerical factor that he determined as precisely as possible by hundreds of experiments. For his measurements, he had to invent a new tool for measuring time on a small scale. Copying the water clock, Mica filled a sealed glass container with sand so that once turned over sand would drip into the adjacent vessel at an unchanging rate. In order to save time, he made the glass vessel symmetrical so that the chamber into which the sand dripped was identical to the chamber in which it started. This simple tool was the first hourglass, a precise and reliable way of measuring the passage of time.

The art of the horologator (clockmaker) had been slowly refined for almost two centuries by specialist craftsmen. Although the solarium (sundial) remained a popular timepiece in plazas and gardens, tasks that required precision depended almost exclusively on a clepsydra (water clock). Since the invention of a compensating tank to keep a constant pressure, the only drawbacks of a water clock - often simply called an horologium (clock) - were evaporation, condensation, limited orientation, and temperature sensitivity, relegating them to a loss of precision in the range of half an hour per day. Temperature remained the greatest problem for the accuracy of water clocks, despite the standards implemented to limit its effects.

Fortunately, most water clocks were only needed as timers, indicating the passage of a certain amount of time, preventing the build-up of errors over several days. One of the few large improvements of clocks after the compensating tank was the invention of a mechanism that counted the times that a container filled with water, before being emptied when full by an escapement. This horological design appeared around 1775 AUC in a clock intended for the public hospital in Septimia. A major trend in clockmaking was the attempt to build larger water clocks. The culmination of this trend was the Horologium Augusti, a facility builton the Campus Martius to replace the Solarium Augusti in Augusta Elysium, whose inaccuracy had been known for centuries.

Feeding a sequence of reservoirs by aqueduct, the Horologium consisted of an enormous mechanism below the ground that slowly raised conspicuous silver pointers up a cylinder standing in a marble plaza on the spot of the old solarium. The cylinder itself was a tower whose position within a semi-circle of bronze lines on the ground turned it into an effective sundial, similar to the solarium. However, the proper measurement of time came from the position of the pointer along the height of the tower, raised by the action of gears driven by an escapement underground, to avoid the known problems with pumping water upward. In this way, the Horologium was both the largest sundial in the world and the first clock tower.

For the operation of its mechanisms, the Horologium had to overcome engineering hurdles in the transfers of high torque. For this purpose, the driving force for the mechanism came from the largest compensating tank used until that point in a water clock and motion was transferred by a complex gear train that employed epicyclic and segmental gearing. For facilitating rotation, many of the components had wooden ball bearings and a mechanism for bearing the weight of the machine while it was stopped for repairs. Replacing and inspecting parts was designed to be a simple process - continuous operability was one of the highest design goals of the entire project, forcing the architects to accept a much smaller structure than they intended.

Dedicated to Caesar Augustus, the tower and plaza displayed ample iconography pertaining to Octavius and his family. As an indicator of the time, there were silver statues of Eros - the son of Aphrodite - in each cardinal direction from the tower, referring to the now merely symbolic ancestry of the first roman emperor. At the top, a 2.96 meter tall golden statue of Octavius stood facing the adjacent Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace).

Mechanisms at the base of the tower allowed the passage of time to be matched to the solar time which varied over the course of a year (i.e. the dial was meant to read the same time at every sunrise and at every sunset). Each sunrise, the pointers were reset to the bottom of the dial while the mechanism was modified to match the day of the year. Standing at 32 meters in height and with pointers the size of a person, the clock could be read from as far away as the Mausoleum of Caesars.

Citizens in the major cities of the Imperium were able to keep track of news through regular postings of the Acta Diurna (Daily Public Records) in their main forums. Among its contents were the activities of public magistrates, major events in foreign countries or distant provinces, and the deaths or marriages of important public figures. Both the Acta Diurna and the Acta Senatus - the publications of senatorial proceedings - were posted in paper, behind sealed glass on large marble boards. These boards were important sites for the average citizen; dozens of people could be found crowding around them every morning, even though the minutes of the Senate were not posted unless there had been an assembly the previous day.

In imitation of these publications and in the spirit of publicare et propigare (making public and propagating), the Technaeum employed the same concept in its Acta Technaea. Organized by an auctor publicus ludanus (Academy Publisher), this weekly posting states the most recent work by scholars at the Technaeum and is a venue for scholars to publish thoughts about the prevailing theories of the time. This Acta was originally posted in Augusta Elysium and Civis Lenape alone but eventually the scholars of the Musaeum pushed to have the same documents published on the grounds of their academy. By this time, the concept of publication boards was common in cities, as municipal senates sometimes copied the procedure of the Senate in publishing their decisions in the local forum and the people of Elysium itself were especially fond of the practice.

To a large extent, the decision to publish the works of scholars at the Technaeum came from the prestige of Pistorius but other scholars also supported the new policy and, in fact, the majority of notices pertained to the work of these others. It was only that the public interest in the creations of the Magnus Machinator (Great Inventor) pushed the Scholarch of the academy to gain attention for his institution by publishing news that the public would find intriguing.