Paladín Wulfen

Kicked

Few citizens had risen through the ranks of the empire as quickly as Fabius. Being named Legatus Augustus of the province of Magnum Fluvius at the age of 31. Fabius proved to be an able consul and the people of Elysium were still sore that he had not returned for a Triumph so when the equally beloved Caesar Ulpius was assassinated without an heir, the Senate had almost no choice but to appoint Fabius its new emperor.

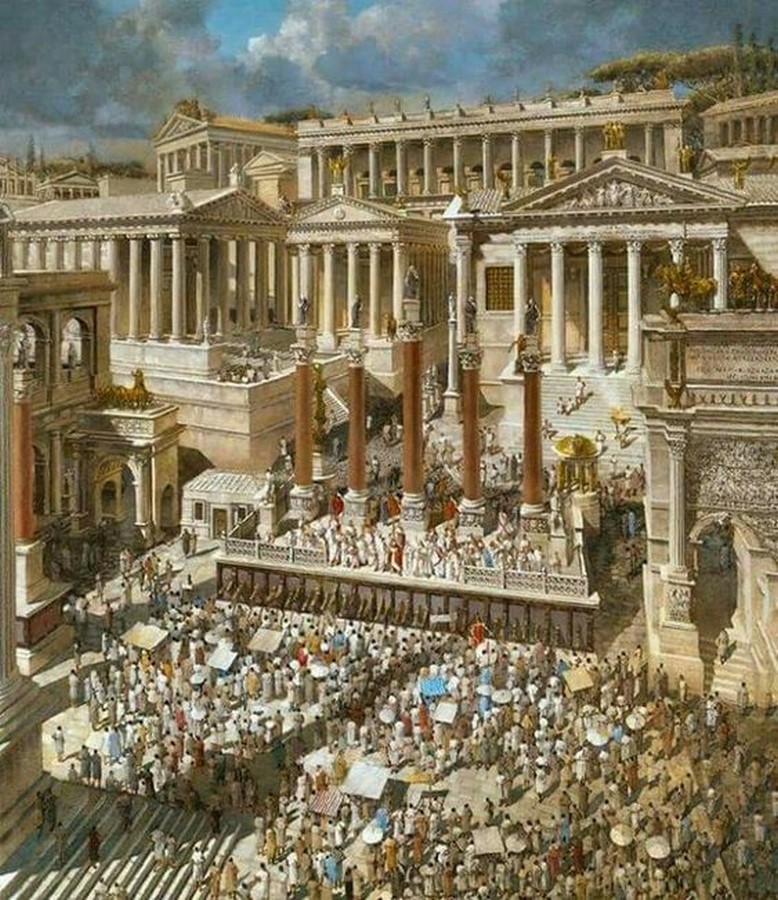

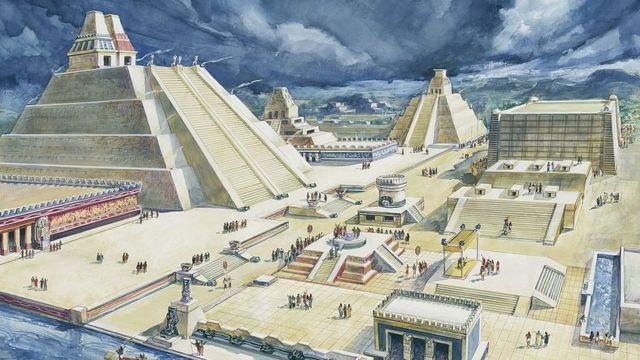

As an emperor of the people, Fabius would go to great lengths during his long reign to keep them happy. Seeking to magnify his parallels with the old and venerable Consuls of Rome, he made one of his first acts the renovation of the Grand Theater Mons Regius and building a colonnade to enclose a new park outside the theater proper. This park had a statue of himself as its centerpiece but also featured religious art and was entered through a victory arch crediting success against the Iroquois. Construction on the theater put the public accounts even further into debt but was met with great enthusiasm from people of all orders. Once this project was finished in 1547, there would be another year before regular tax revenues returned and grain subsidies for Alexandria could be halted, since food shipping routes would reopen once the plague subsided. Despite the admonition of the Senate, Fabius refused to cut the various expenditures that he would come up with each year, keeping the state in debt.

As an emperor of the people, Fabius would go to great lengths during his long reign to keep them happy. Seeking to magnify his parallels with the old and venerable Consuls of Rome, he made one of his first acts the renovation of the Grand Theater Mons Regius and building a colonnade to enclose a new park outside the theater proper. This park had a statue of himself as its centerpiece but also featured religious art and was entered through a victory arch crediting success against the Iroquois. Construction on the theater put the public accounts even further into debt but was met with great enthusiasm from people of all orders. Once this project was finished in 1547, there would be another year before regular tax revenues returned and grain subsidies for Alexandria could be halted, since food shipping routes would reopen once the plague subsided. Despite the admonition of the Senate, Fabius refused to cut the various expenditures that he would come up with each year, keeping the state in debt.

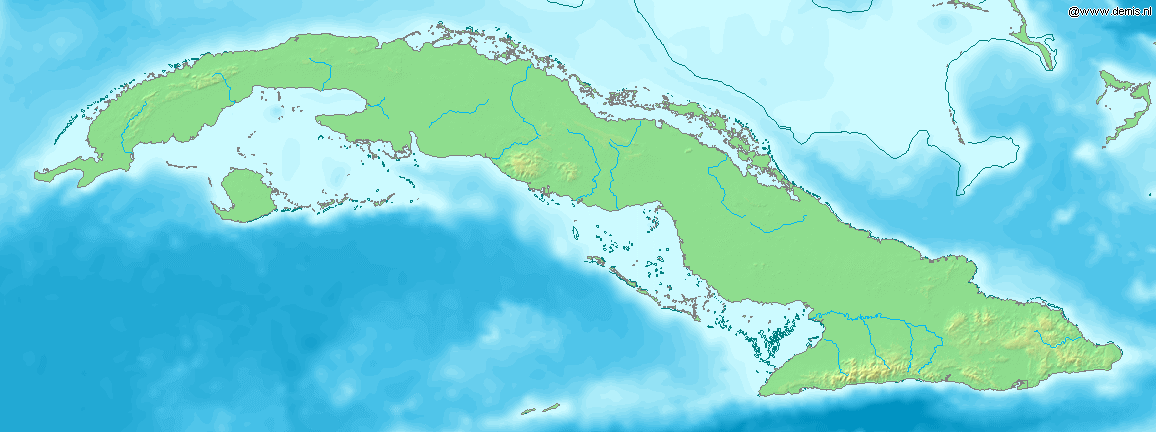

Starting in 1545, the idea of digging a Lenape canal (OTL: Erie Canal) across the isthmus was revived in the Senate as a means of more closely connecting the provinces. Only getting underway, once the plague subsided, the canal took 15 years to complete and cost 70 million Dn. Overall, the excavation went through ~584 km of land at a base width of ~28 meters that widened as the walls of the canal rose. The width of the canal was sufficient for traffic to go in both directions.

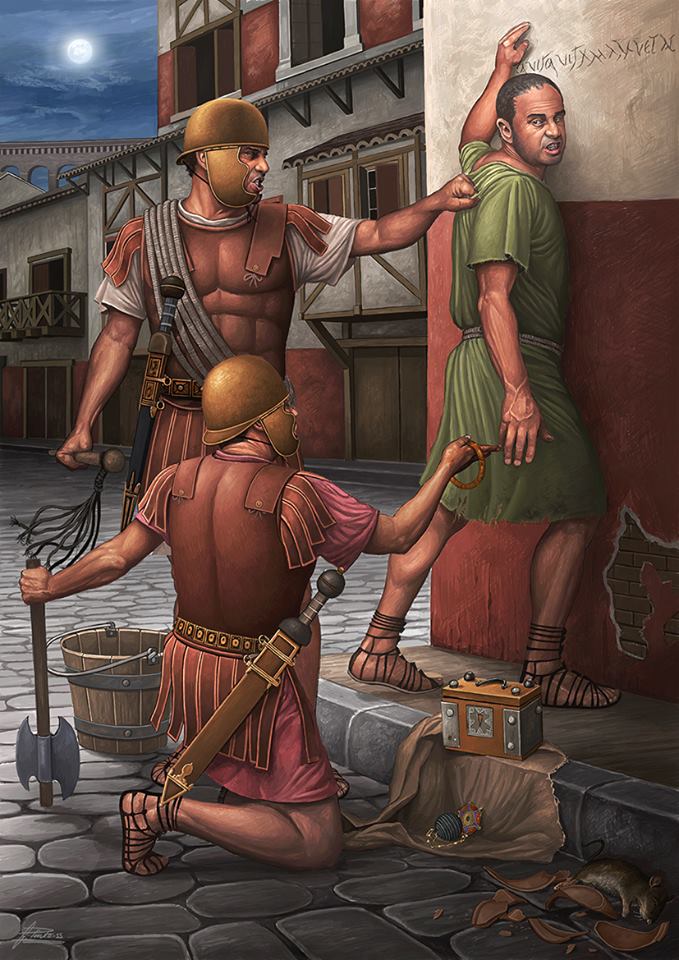

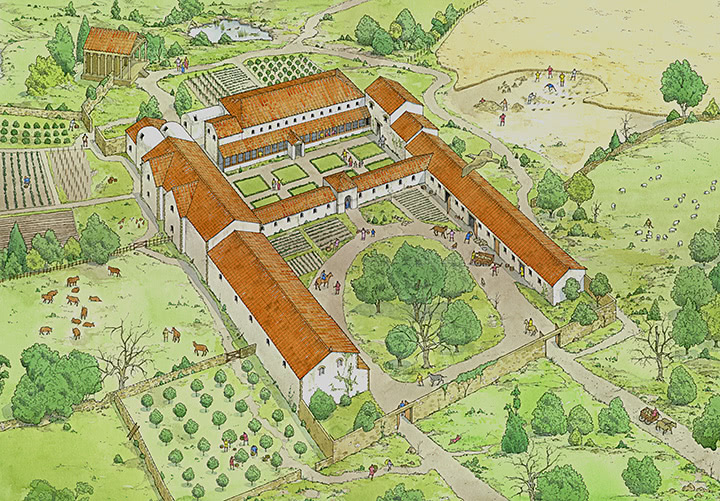

For public entertainment, Fabius financed grand public games in Augusta Elysium and in major cities. Animals would be shipped in large quantities from every land possible for local gladiators to fight to the death. Enough gladiator slaves were dying or gaining their own freedom that their numbers reached an all-time low. In fact, the number of slaves in general had fallen to about 5 million out of a total population of 69 million people (after over nine million people died from the Ulpian plague). While Fabius cared little about the falling total number of slaves, he was concerned about gladiatorial matches becoming more difficult to hold. To slow the decline, he arranged to buy agricultural slaves from the aristocracy for high prices. By the end of his reign, the number of slaves would fall to a historic 4 million slaves, from a combination of manumission, natural attrition, and death in the arena. Since a maximum number under Kaeso Iulius Caesar, slaves had slowly become less numerous in the Empire. Laws were passed to restrict manumission and encourage the birth of vernae (slaves born to slaves) but these tended to be house slaves as emperors were not especially fond of the latifundia (landed estates) of the aristocracy, where the majority of Elysium's agricultural slaves would work. At the end of his reign, Fabius had effectively left a situation where the owners of latifundia would never release their agricultural slaves and would heavily encourage their slaves to have children. Slave markets were basically only selling vernae from whatever sources were available, although a few small wars would occasionally supply markets.

For public entertainment, Fabius financed grand public games in Augusta Elysium and in major cities. Animals would be shipped in large quantities from every land possible for local gladiators to fight to the death. Enough gladiator slaves were dying or gaining their own freedom that their numbers reached an all-time low. In fact, the number of slaves in general had fallen to about 5 million out of a total population of 69 million people (after over nine million people died from the Ulpian plague). While Fabius cared little about the falling total number of slaves, he was concerned about gladiatorial matches becoming more difficult to hold. To slow the decline, he arranged to buy agricultural slaves from the aristocracy for high prices. By the end of his reign, the number of slaves would fall to a historic 4 million slaves, from a combination of manumission, natural attrition, and death in the arena. Since a maximum number under Kaeso Iulius Caesar, slaves had slowly become less numerous in the Empire. Laws were passed to restrict manumission and encourage the birth of vernae (slaves born to slaves) but these tended to be house slaves as emperors were not especially fond of the latifundia (landed estates) of the aristocracy, where the majority of Elysium's agricultural slaves would work. At the end of his reign, Fabius had effectively left a situation where the owners of latifundia would never release their agricultural slaves and would heavily encourage their slaves to have children. Slave markets were basically only selling vernae from whatever sources were available, although a few small wars would occasionally supply markets.

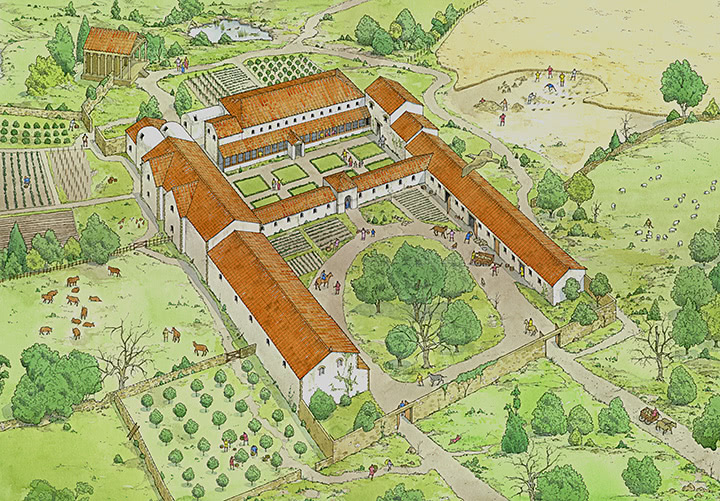

As wealthy landowners weakened, the landholding plebeian grew in prominence. These lower class farmers were the backbone of the agricultural industry in the borders, since ager publicus (public land) acquired by the emperor would be prioritized as gifts for retiring legionaries and the urban poor. Emperors before Ulpius had devoted millions of denarii each year toward encouraging such settlement and Fabius would continue this trend after it slowed during the crises of the previous few decades.

As wealthy landowners weakened, the landholding plebeian grew in prominence. These lower class farmers were the backbone of the agricultural industry in the borders, since ager publicus (public land) acquired by the emperor would be prioritized as gifts for retiring legionaries and the urban poor. Emperors before Ulpius had devoted millions of denarii each year toward encouraging such settlement and Fabius would continue this trend after it slowed during the crises of the previous few decades.

The firsts emperors had supported lower class farming by buying latifundia but these had been resold to patricians by Caesar Maximius. As the number of slaves fell, these would become less profitable for wealthy landowners, leading them to sell their private land back to the emperor who gave the land to retiring legionaries and leased the rest to plebeians in a manner similar to what had pioneered. Over time, these properties would either be sold to whomever was leasing the land or given to legionaries retiring from military service. There had been quite some time since Elysian estates could be given to veterans in return for their services to the empire and the resurgence of this particular donative greatly pleased the middle classes. As a signal of this peace, Fabius disbanded two legions. There had been obstacles in replenishing the ranks of fallen legions from the war and those legions which disappeared were already functionally gone.

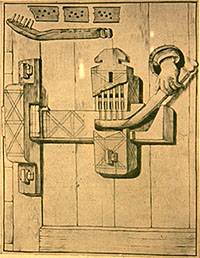

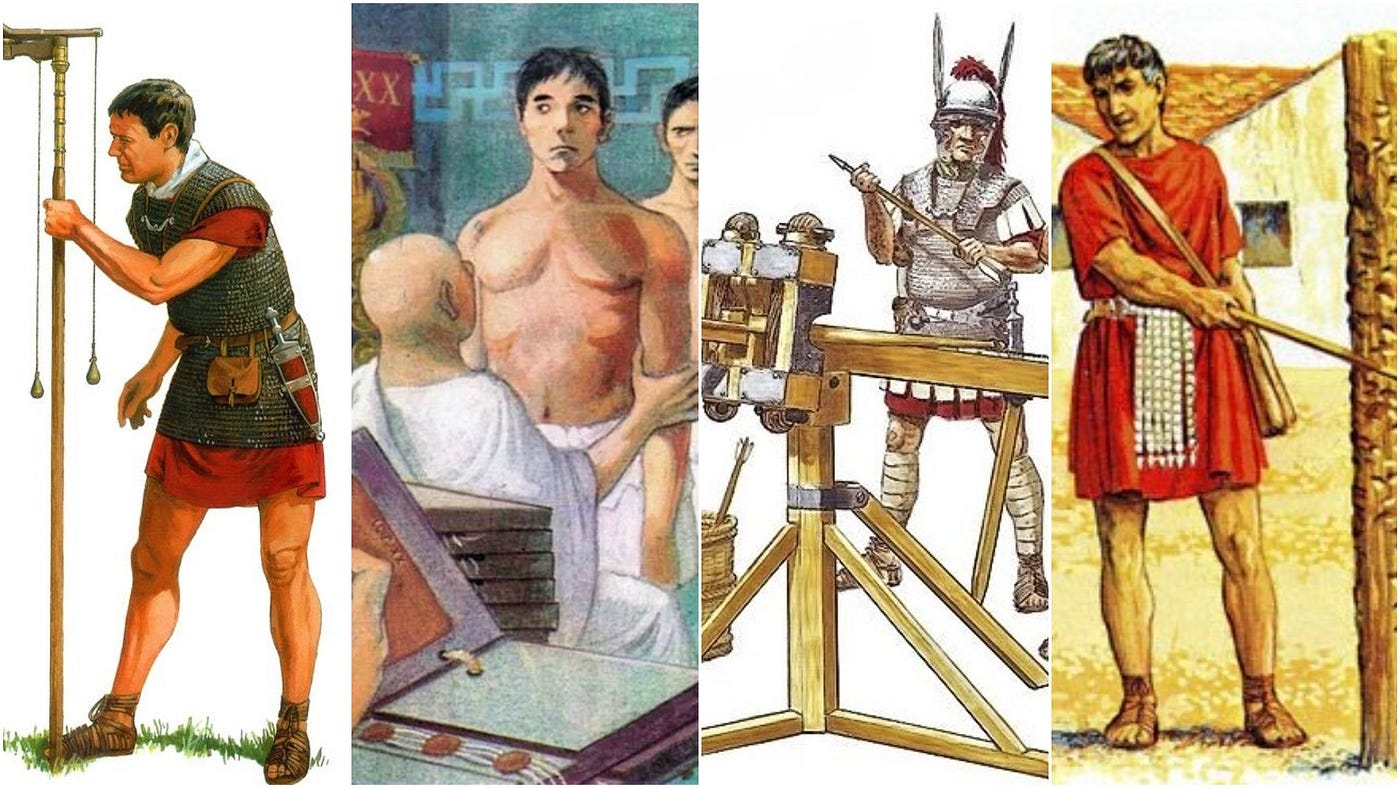

Impressed with the few inventions of ballistarii (artillerymen) training in the Academia Bellica (War Academy), Fabius sought to encourage their creativity for weapons by devoting a school there to the study of siege engines. The emperor personally went, over the course of the 1550s, to hire the finest mathematicians and the most renowned experts on Aristotelian physics for the school. Although one of its focuses would be to give better training to aspiring artillerymen, through five years of schooling, this wing of the War Academy would also be a space for mathematicians and natural philosophers to improve upon existing weapons.

Impressed with the few inventions of ballistarii (artillerymen) training in the Academia Bellica (War Academy), Fabius sought to encourage their creativity for weapons by devoting a school there to the study of siege engines. The emperor personally went, over the course of the 1550s, to hire the finest mathematicians and the most renowned experts on Aristotelian physics for the school. Although one of its focuses would be to give better training to aspiring artillerymen, through five years of schooling, this wing of the War Academy would also be a space for mathematicians and natural philosophers to improve upon existing weapons.

A primary facet of training for artillery work was knowing how to manufacture and repair siege weapons so the interaction of the teachers with more experienced students would be a good opportunity for bringing fresh understanding to the study of weapons. Such opportunities were a result of the shift in spirit of the new artillery school from the older school where veteran artillerymen would teach newcomers their art. This new school was for understanding and using Elysean siege equipment, as well as other pieces of military equipment, and its result was more valuable ballistarii than could be trained in the field.

In fact, there was such a gap between the skills of graduates from the new artillery school and field trained artillerymen that the emperor was forced to acknowledge this difference with an increase in pay - double the pay of a regular ballistarius. Fabius promised the school an annual fund of 9 million denarii both for paying its teachers, known as doctores ballistarii, and for buying materials for siege equipment. This stipend exceeded funding for the rest of the War Academy. Over his reign, this Technaeum Armarum et Armaturae (Technical School for Arms and Armor) would produce a leather bracer for archers to avoid wearing down their arms, sturdier assemblies for the manuballista, polyboloi, carroballista, and regular ballista, and a mount for rapidly deploying stationary artillery on parapets (since they are usually stored nearby during peacetime). Small changes to existing lorica (body armor), sword, arcus (bow), and ballista (siege engine) designs would gradually improve the cost, sturdiness, reload time, and strain of some of these weapons, at a faster pace than before the Technaeum's existence. Prior to its completion, there were some mathematicians, artillerymen, and natural philosophers who would occasionally come up with better designs (as is the case for the lignaballista in decaremes) but this school ushered in an era of directed research.

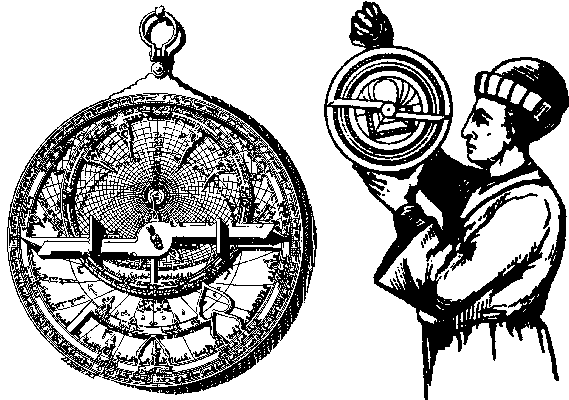

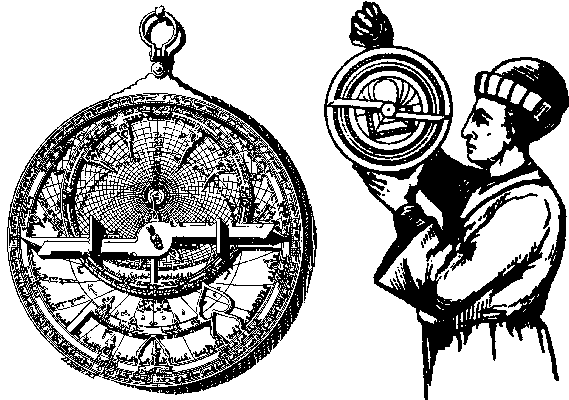

Another invention of the Technaeum around 1555 was a stone wheel operated by pedal that could used to sharpen iron. This simple grindstone went into regular use by the Legion and appeared in smithies in the form of a water-powered grinding wheel. The whetstone would also inspire the polishing and grinding wheels for glass lenses when those were invented a century later. For the navy, one geometer invented the cross-staff that measured the distance of a celestial body from the horizon. This simple tool would be the predecessor for the backstaff, invented at the Technaeum to measure the position of the Sun without staring in its direction, and eventually the mariner's astrolabe, invented to replace the quadrant but inspired by the astrolabe and backstaff that were in heavy use when geometers at the Technaeum created the first mariner's version. Without this school where geometers and philosophers could freely develop their ideas, it is doubtless that these navigational tools would not have come into existence as early as they did.

Another invention of the Technaeum around 1555 was a stone wheel operated by pedal that could used to sharpen iron. This simple grindstone went into regular use by the Legion and appeared in smithies in the form of a water-powered grinding wheel. The whetstone would also inspire the polishing and grinding wheels for glass lenses when those were invented a century later. For the navy, one geometer invented the cross-staff that measured the distance of a celestial body from the horizon. This simple tool would be the predecessor for the backstaff, invented at the Technaeum to measure the position of the Sun without staring in its direction, and eventually the mariner's astrolabe, invented to replace the quadrant but inspired by the astrolabe and backstaff that were in heavy use when geometers at the Technaeum created the first mariner's version. Without this school where geometers and philosophers could freely develop their ideas, it is doubtless that these navigational tools would not have come into existence as early as they did.

Indeed, the new level of support by an emperor for technological research had few precedents in earlier history, perhaps only in the patronage of Aristotle by Alexander the Great or the support of court scholars by Chinese emperors. The degrees to which future Elysean emperors would fund the Technaeum would vary but there was always enough funding to support a large staff, even if the institution could not afford many materials for bringing new ideas into reality.

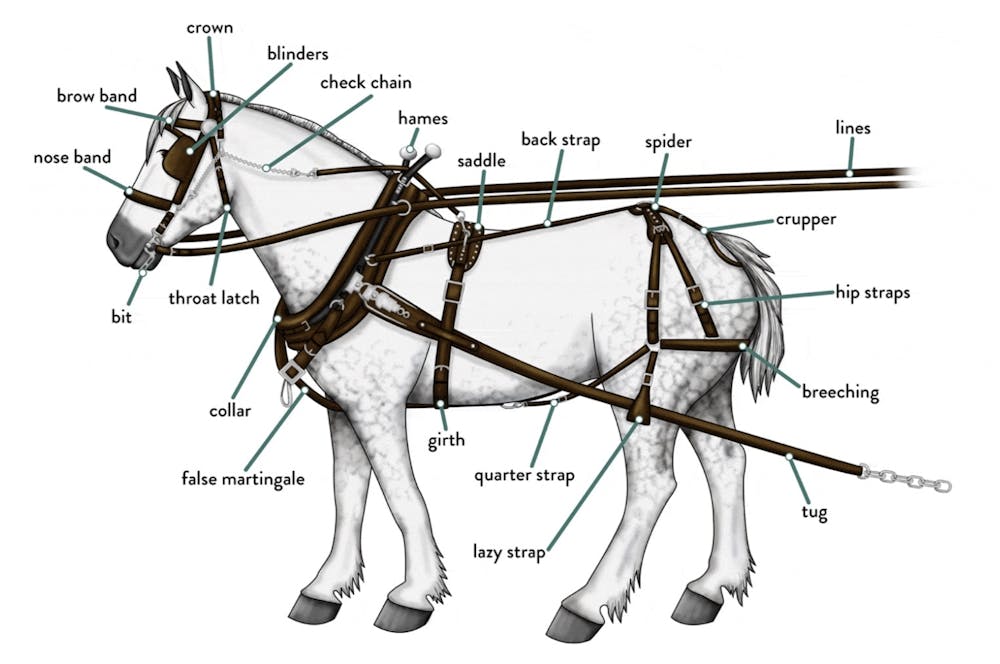

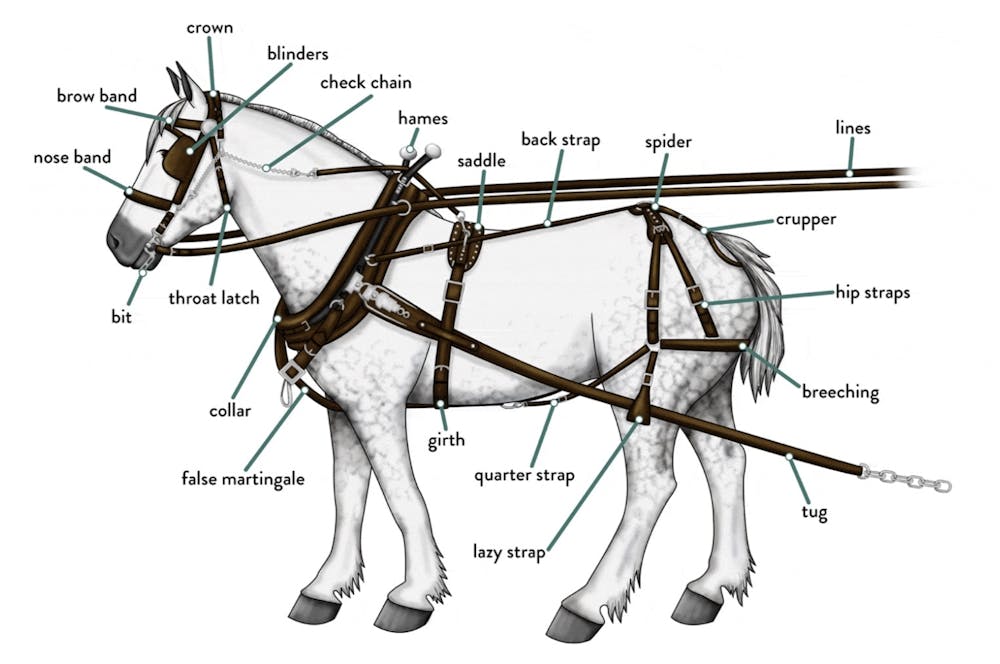

Meanwhile, inventors from the Western provinces were bringing other inventions. A unique horse collar, attaching to the breast rather than above the neck, had spread to farmers, allowing replacement of oxen with horses. A horse had greater speed and endurance than an ox, providing roughly 50% more efficient plowing. The breastcollar would be surpassed by another invention, the collar harness, that would guarantee the dominance of horses in agriculture. Widespread use of the breastcollar took about 50 to 60 years to arrive but the collar harness would be much more readily received, spreading from its introduction in the 1550s to the recognition of emperors for used around 1580. Farmers especially benefited from this invention, alleviating some of the difficulty of working with hard soil.

Meanwhile, inventors from the Western provinces were bringing other inventions. A unique horse collar, attaching to the breast rather than above the neck, had spread to farmers, allowing replacement of oxen with horses. A horse had greater speed and endurance than an ox, providing roughly 50% more efficient plowing. The breastcollar would be surpassed by another invention, the collar harness, that would guarantee the dominance of horses in agriculture. Widespread use of the breastcollar took about 50 to 60 years to arrive but the collar harness would be much more readily received, spreading from its introduction in the 1550s to the recognition of emperors for used around 1580. Farmers especially benefited from this invention, alleviating some of the difficulty of working with hard soil.

By this time, the iron horseshoe had almost totally replaced the hipposandal as the preferred soleae ferrae for horses in the Empire. The latter would only be strapped to the hooves whereas the new solea ferra was nailed to the hoof of a horse. Horseshoes were far more comfortable for horses and more firmly gripped the hoof than the hipposandal, allowing their use in race and courier horses that moved quickly on often hard surfaces. When the horseshoe had become standard for horses used by the cursus velox (fast postal service), the mutationes (change stations) for switching horses could carry as low as a third as many horses as before since their rest period could be substantially shorter. Farmers had also benefitted from use of horseshoes, as had the iron industry that met the massive demand for the new hoofwear. The reign of Fabius saw the introduction of how advantageous founding a center for weapons research. He would not allow Elysium to be exceeded by great foreigner empires, with their advanced technology. Instead, Elysium would be the one to lead the world in weaponry, using her advantages in machine technology.

During this time of peace, Elysium literature entered its second golden age, led by poets, political theorists, historians, and a few notable playwrights. As literature flourished, a group of patricians (aristocrats) formed a conservative writing club that opposed some of the recent and prior developments in the lingua latina (Latin tongue). In an attempt to encourage traditional spelling and pronunciation, these senators and businessmen bought out several ludi litterarii (elementary schools) operating out of Agusta Elysium around 1572, forcing the teachers to safeguard the future of the imperial language of Latin. At the same time, these reactionaries sought change for Latin, with a stated desire to remove the "impurities" that had settled into the language.

Seeking the patronage of the treasury, the club began to issue pamphlets to other aristocrats, lamenting the corruption of Latin by the vulgar forms spoken by provincials. Indeed, the rise of a vulgar latin (latina truncata) had not gone unnoticed in high society, nor had earlier but less severe bastardizations of the language (i.e. accents and idioms) been ignored. Aristocrats being how they were, many people were supportive of the ideals of the group and it did not take long before the Senate had passed a bill that called for the formation of a societas (institution) devoted to the preservation, purification, and proper evolution of Latin.

In this way, the Societas Latinae (Latin Institute) was founded in 1579 by advice of the Senate. Over its first decade, the Institute brought all of the ludi litterarii in the capital under its wing and created the first permanent elementary school (as other litterarii only operated in gardens, houses, basilicas, temples, or plazas) on a plot of land in the Horti Maecenatis (Gardens of Maecenas) gifted to the Institute by Caesar Fabius. For the time being, this school building and attached library would be the only permanent facility for the Institute, a precursor to its future influence.

Growing in membership, the Institute became an anchor in the development of Latin. Although its direct influence was small at the start, its unflinching persistence in its conception of the language would have a delayed effect on the Latin of city-dwellers but an effect nonetheless. Over time, the Latin of distant cities persistently drifted closer to this one fixed point, at a rate that only rose with the influence of the Institute.

Only the Atomist school countered the worldview of creation, as perhaps the sole non-Religious philosophical school. One of their core beliefs was that ex nihilo nihil fit (nothing comes from nothing) and therefore, whatever exists can be neither created or destroyed, only changed in form. Atoms are what exist and the void is what does not exist - for Epicureans, there was nothing else than atoms moving through the infinite void. By this time, only one philosopher still associated himself with this school of philosophy, the last vestige of a dying position. Dionada of Septimia was how he would be remembered, primarily for his treatise written in 1558 as an attempt to dismantle Aristotelian physics.

De Motu (On Motion) was a brilliant synthesis of geometry and atomism. While Aristotelian physics was in vogue for theorizing about nature, geometricians were the driving force behind the last millennium of advances in machinery. As pioneered by the great Archimedes, geometry alone informed how moving parts could be arranged to instigate motion in a desired direction, often with tremendous precision. Romans understood the principle that an action in one direction would induce motion in that direction and they knew the direction of the actions of ropes, gears, and other machines. Dionada interpreted this geometry of machinery in terms of moving atoms, where motion would be linearly transferred from one atom to another by collision.

Central to his philosophical system was the principle that an atom travels straight unless it collides with another atom. He said that every atom contained a certain amount of conata (efforts) toward one direction, preventing the atom from slowing down or changing direction once in motion (unlike Aristotle who believed that motion required constant action from an effective cause or a teleological cause, for forced and natural motion respectively). When two atoms collided, there was an exchange of conata that resulted in new directions and speeds for the atoms. The final state after a collision depends on the geometry and quantity of the initial conata of the atoms before that collision, such that both the total conata and the sums of conata in every direction had to be preserved. This primitive law of conversation of momentum was motivated by a need to explain how the new motion of atoms would be decided after a collision, since this was the only law which uniquely determined the final motion of the atoms.

In general, the total conata of any object had to be proportional to both its speed and its weight. Some objects could even be heavy enough that nothing else could impart enough conata for noticeable motion - the Earth served as Dionada's example here.

Exchange of conata could be used to explain why every moving object slows down to rest. Atomists considered the atoms in a solid state to be strongly connected such that dislodging atoms was difficult, although not impossible as breaking demonstrates. For this reason, the touching of two solids along a surface - such as a foot on flat rock - imparted conata from the moving foot into the heavy ground (even, as Dionada asserted, if the two surfaces were perfectly flat as he could show with metal plates). When something slides over the ground, it imparts its conata into the atoms of the heavier solid ground - Dionada notes that this is the reason dirt gets kicked up when bolts or stones from siege weapons strike soil.

Contrary to Aristotelians, who argue that air is what causes an arrow to be propelled in flight, Dionada believed that repeated collisions with atoms of air would slowly disperse the conata of the arrow into the air, slowing the projectile down. Similarly, wind would only be an organized motion of atoms in the air, building the conatus of a ship through collisions with its sails. All of these general principles were presented in specific parts of De Motu, as the majority of the text had been devoted to explaining the motion of specific machines with these principles to connect macroscopic motion with the motion of atoms.

Not only did Dionada theorize on collisions between atoms but he also had ideas for how atoms became attached. There were two classes of solid materials in Dionada's theory: elastikos (extensible) and akamptos (inextensible or rigid) solids. Atoms of the former kind were supposedly loosely connected, sharing certain qualities with liquids in being able to change shape, while atoms of the latter were said to be strongly connected, resisting changes to the macroscopic arrangement of the material.

A number of materials were recognized by Dionada as extensible. Most fibers could be stretched - a property that found its use in the simple arcus (bow) which men had known for millennia. Under some contexts, metals could be stretched but they could also be compressed, a process that Dionada described as subject to the same rules as stretching. In particular, Dionada talked about metallic springs, such as the simple leaf springs that had replaced cheaper wooden leaf springs in the suspension of carriages used for the Collegium Itinerarium (Public Transportation Guild), consequently coming into use. Aside from leaf springs, Dionada also described the metallic v-spring used in non-military crossbows to reduce trigger sensitivity. No one before Dionada had described all springs in a single treatise, since a category "spring" had not existed. Dionada did not stop at describing springs, but went as far as to explain their behavior.

When stretched, an extensible material was descrbed as "hav[ing] an inclination toward its natural arrangement", explained by saying that the strength of the connection grew as the material became more extended. Dionada considered connection to be the second kind of interaction between atoms, other than collision. His explanation was that atoms had an innate tendency to joining together with other atoms of the same kind, such that "a great bulk of atoms would pull on other atoms as if by iron rope". This theory of material attraction was how Dionada explained gravity, elasticity, and stickiness. In general, Dionada argued that the strength of atomic attraction increased as clumped together atoms diverged from their natural arrangement (hence, a stretched bowstring would deliver more conata into its arrow the farther it stretches). On the basis of how this broad explanation fits a number of observations, Dionada showed that the strength of an elastic material's inclination to restore its natural shape was proportional to the amount it has presently stretched from its natural position.

A number of other theories are mentioned in passing by Dionada. First, he argued that the Earth is the result of a majority of the atoms in the cosmos ultimately settling into one place by their attractive inclination. Second, he compared the motion of the Sun and stars around the Earth with that of "an arrow that eternally misses its target", saying that celestial bodies were constantly falling toward the Earth (as the heaviest thing in existence) in such a way that they always missed. Third, he explained motion of the wandering stars (planetes) by a "lesser bulk of earth" following the deferent orbit around Earth while the visible star that would follow an epicyclical orbit centered on this mass, even as it also orbited the Earth along the deferent path. Lastly, the rising of fire was explained by a difference in inclination between fire and air, wherein the latter atoms had a stronger attraction that forced the fire atoms out of the way so that "[fire] seems to rise as air falls into its place". Bubbles of air rising through water were taken to follow the same principle, which he further extended as an explanation for the buoyancy of wood in water.

Unfortunately for the development of human knowledge, this book was widely taken to be just another polemic of an Epicurean against Aristotelianism and for this reason, its theories were ignored by most philosophers. De Motu would be the most accurate treatise on physics for some time, presenting a number of primitive ideas that would inspire modern mechanics. One observation, first noticed in De Motu, that would gain a wider audience was the fact that a lodestone bar would always orient itself along the same direction when freely suspended, a discovery Dionada attributed to one of his colleagues.

Since this direction was North-South, Dionada suggested that the lodestone could be used for navigation, by hanging a straight piece of lodestone by a string somewhere on a ship. While no one knows why there are no works on lodestones written by his unnamed colleague (who likely died during the early tenure of Dionada at the Musaeum), Dionada himself commissioned smiths to work pieces of lodestone into bars for selling to merchants coming into Alexandria. Within a century, nearly a fifth of ships in the empire had their own compass (dirigator), mostly ships going to the Erythraean Sea or traveling along the Atlantic coast.

Some nobles and people who spent time at sea started keeping a small dish of water, in which a lodestone was suspended, as a decoration in their home. The household compass made its owner seem to have an interest in travel to far away places and gave the appearance of wanting a constant reminder of the cardinal directions proscribed by Nature.

The reign of Fabius is regarded as the start of a golden age of Elysium mathematics, with mathematicians in the Musaeum and Technaeum renewing their level of discovery after almost three centuries of lacking progress. Dionada likely drew some of the inspiration for his work from this resurgence of mathematics.

The mathematician Aulus Gidius Agris wrote an original treatise in 1545 that detailed both elaborate and simple methods for merchants to work with different types of quantities. There were many other works of this sort written in Italy, Egypt, and Arabia Petraea over the last few centuries but this piece stood above the rest. Among the topics of his Ars Mercatura are: areas of rectangular and irregularly-shaped fields, volumes of solids of various shapes, a pre-algebraic method of double false position for linear interpolation, and a method for extracting roots. Foremost among his original methods was a method of elimination for solving a system of linear equations as an array of numbers. This procedure was the earliest step toward matrices in Western mathematics, discovered independently from its invention in China before 100 BCE.

A commentary written in 1571 on the Ars Mercatura has the first suggestion of negative numbers as a means of replacing some of the awkward terminology used by the original author. In particular, the author of this commentary equated a deficit or a debt with a different sort of number in practice than the positive rational numbers known to mathematics. The same author seems to have annotated a copy of the Arithmetica of Diophantus of Alexandria to note that negative rationals would offer additional solutions to some of his problems, solutions not considered by the famous Alexandrian. Unfortunately, the commentaries would never be published to a wider audience, only receiving occasional attention whenever noticed by scholars working at the Musaeum where they joined the shelves of its library.

Around 1576, the mathematician Aetiales of Lenape published a treatise on trigonometry. For his book, Aetiales invented three new trigonometric relationships between the sides of a triangle and its angles. These relationships were radius (cosine) semichordis (sine), and anteradius (versine), with semichordis defined as the relation of half a chord with half its angle. A number of well-known trigonometric theorems were rewritten in terms of these new relationships, that Aetiales described as more convenient than the chord relationship used by his contemporaries. The image of a circle circumscribing a triangle with these quantities displayed would become ubiquitous for trigonometry from this century onwards.

Applying his own algorithm to a 12,288-sided figure, Aetiales computed a value of 355/113 for the number pi, lamenting that he could go no further. Although this was a landmark achievement for Western mathematics, Aetiales made perhaps his greatest contribution to the empire through his textbook on geometry relevant to contemporary siege engines (a feat that overshadowed the treatise of Dionada, done as it was by a New Platonist who was also the Scholarch (headmaster) of the Technaeum).

Between these major discoveries was the general expansion of the Euclidean system of geometry, with mathematicians adding a number of original theorems about conic sections and triangles. However, these discoveries were characteristic of the same limited progress that had occurred since the writings of Diophantus, with some historians not even including them in their treatment of this period of Roman mathematics.

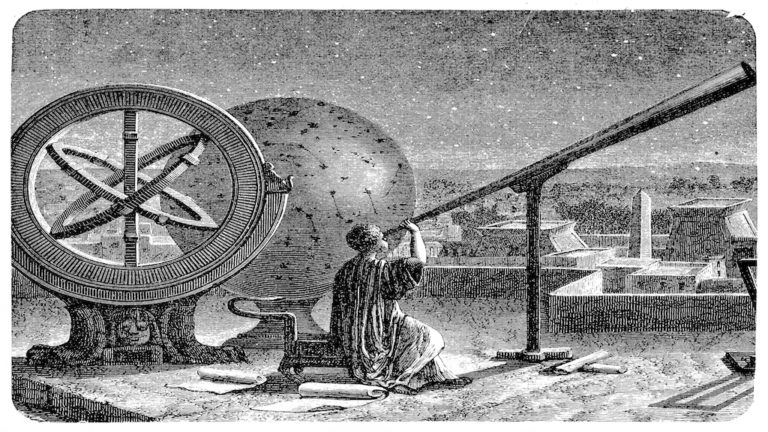

Astronomy (astronomia) had been the most sophisticated science practiced by Elysium philosophers and mathematicians since the Roman empire conquered Greece. By the 8th century, mathematicians at various institutions in the empire had spent centuries refining the Ptolemaic model of the solar system, although none added to the complexity of the epicyclic orbits of the planets. However, the reign of Fabius is notable for a slow rise in the prominence of astronomical observation in astronomy, where earlier scholars in the field placed the most emphasis on astronomical calculations. This trend accelerated toward the end of the 6th century as newer instruments such as the mariner's astrolabe were being invented.

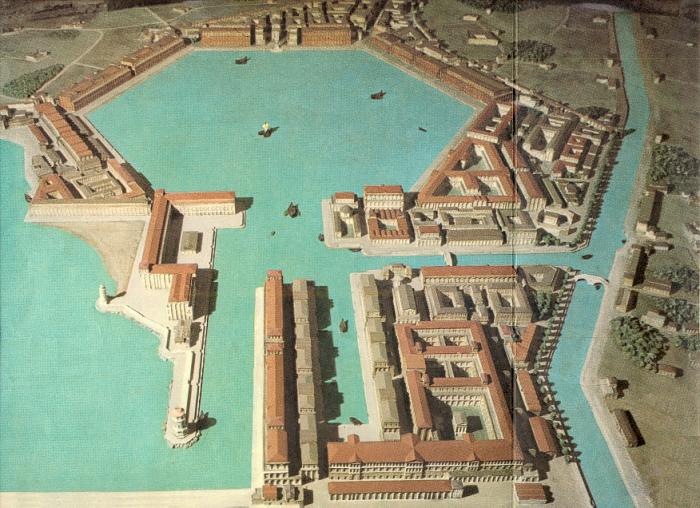

A famous invention from this period, often considered symbolic of the scientific and artistic golden age that characterized the reign of Fabius, was the Circumspecta Caelesphaerium (literally the Circular Viewing Chamber of the Celestial Sphere). Constructed as a facility for the Musaeum, the 29 meter diameter dome for this structure was completed in 1574. A thin tunnel on the southern end of the dome was the only entrance to the viewing platform within the dome. At the center of the platform was a bronze sphere with a detailed depiction of the known Earth, since the ancient lands of Roman Empire in Europe, too Africa and Asia even North Europa like Escandinavia too Elysium and other lands near the Empire. From the viewing platform, a complete representation of the celestial sphere, including every known star and constellation, was visible, with only a single hemisphere able to be viewed at a time. The implication of this system is that an enormous machine was needed to rotate the celestial sphere around the axis of the entrance tunnel. These mechanisms were robust but their sheer size demanded care from the team of slaves tasked with rotating the entire chamber on the demand of astronomers from the Musaeum.

Not only were stars and their constellations mapped onto the great sphere but a line of gold marked the ecliptic (path of the Sun), with notes along the length of the ecliptic that specified its located across each month. Known to the scholars of the Musaeum as the Ephemeris Magnis (Great Star Chart) or simply the ephemeris, this massive diagram served as the most accurate map of the night sky in the known world, presenting information that was otherwise only available in tables of numbers or in armillary spheres. Directly outside the chamber was a mechanical armillary sphere, with elaborate mechanisms that precisely followed the motions of the Moon and the Sun. Motion of the projected positions of the Sun and Moon coincided with the rotation of a wheel and was designed to follow a mechanical computation of the Enneadecaeteris (also known as the astronomical cycle of Meton). Using this machine, the phases of the Moon could be computed for any day of any year. Unfortunately, the predictions of this device suffered increasing inaccuracy as time passed, forcing its replacement by a machine with updated parameters.

Together, these two devices gave Septimian astronomers an unprecendented capacity to analyze the celestial sphere, paving the way for future advances in the Roman understanding of nature and inspiring thousands of future astronomers. Small replicas of the Ephemeris Magnis began to appear in the homes of astronomers outside of Septimia, with the difference that their chart was etched onto the outer surface of a globe rather than the inner surface of a sphere. By the 8th century, a caelesphaerium was a popular item for navigators, merchants, and the nobility, keeping one in their homes as a sign of worldliness and knowledge to their guests (in a similar manner to the displaying a compass in one's home). With his victories and long, stable reign, Fabius has gone down as one of the most highly regarded emperors in Elysium history, presiding over a golden age in its civilization. This period would serve as a reminder that her strength had not waned, inspiring future emperors to eventually further the glory of Elysium.

Starting in 1545, the idea of digging a Lenape canal (OTL: Erie Canal) across the isthmus was revived in the Senate as a means of more closely connecting the provinces. Only getting underway, once the plague subsided, the canal took 15 years to complete and cost 70 million Dn. Overall, the excavation went through ~584 km of land at a base width of ~28 meters that widened as the walls of the canal rose. The width of the canal was sufficient for traffic to go in both directions.

The firsts emperors had supported lower class farming by buying latifundia but these had been resold to patricians by Caesar Maximius. As the number of slaves fell, these would become less profitable for wealthy landowners, leading them to sell their private land back to the emperor who gave the land to retiring legionaries and leased the rest to plebeians in a manner similar to what had pioneered. Over time, these properties would either be sold to whomever was leasing the land or given to legionaries retiring from military service. There had been quite some time since Elysian estates could be given to veterans in return for their services to the empire and the resurgence of this particular donative greatly pleased the middle classes. As a signal of this peace, Fabius disbanded two legions. There had been obstacles in replenishing the ranks of fallen legions from the war and those legions which disappeared were already functionally gone.

A primary facet of training for artillery work was knowing how to manufacture and repair siege weapons so the interaction of the teachers with more experienced students would be a good opportunity for bringing fresh understanding to the study of weapons. Such opportunities were a result of the shift in spirit of the new artillery school from the older school where veteran artillerymen would teach newcomers their art. This new school was for understanding and using Elysean siege equipment, as well as other pieces of military equipment, and its result was more valuable ballistarii than could be trained in the field.

In fact, there was such a gap between the skills of graduates from the new artillery school and field trained artillerymen that the emperor was forced to acknowledge this difference with an increase in pay - double the pay of a regular ballistarius. Fabius promised the school an annual fund of 9 million denarii both for paying its teachers, known as doctores ballistarii, and for buying materials for siege equipment. This stipend exceeded funding for the rest of the War Academy. Over his reign, this Technaeum Armarum et Armaturae (Technical School for Arms and Armor) would produce a leather bracer for archers to avoid wearing down their arms, sturdier assemblies for the manuballista, polyboloi, carroballista, and regular ballista, and a mount for rapidly deploying stationary artillery on parapets (since they are usually stored nearby during peacetime). Small changes to existing lorica (body armor), sword, arcus (bow), and ballista (siege engine) designs would gradually improve the cost, sturdiness, reload time, and strain of some of these weapons, at a faster pace than before the Technaeum's existence. Prior to its completion, there were some mathematicians, artillerymen, and natural philosophers who would occasionally come up with better designs (as is the case for the lignaballista in decaremes) but this school ushered in an era of directed research.

Indeed, the new level of support by an emperor for technological research had few precedents in earlier history, perhaps only in the patronage of Aristotle by Alexander the Great or the support of court scholars by Chinese emperors. The degrees to which future Elysean emperors would fund the Technaeum would vary but there was always enough funding to support a large staff, even if the institution could not afford many materials for bringing new ideas into reality.

By this time, the iron horseshoe had almost totally replaced the hipposandal as the preferred soleae ferrae for horses in the Empire. The latter would only be strapped to the hooves whereas the new solea ferra was nailed to the hoof of a horse. Horseshoes were far more comfortable for horses and more firmly gripped the hoof than the hipposandal, allowing their use in race and courier horses that moved quickly on often hard surfaces. When the horseshoe had become standard for horses used by the cursus velox (fast postal service), the mutationes (change stations) for switching horses could carry as low as a third as many horses as before since their rest period could be substantially shorter. Farmers had also benefitted from use of horseshoes, as had the iron industry that met the massive demand for the new hoofwear. The reign of Fabius saw the introduction of how advantageous founding a center for weapons research. He would not allow Elysium to be exceeded by great foreigner empires, with their advanced technology. Instead, Elysium would be the one to lead the world in weaponry, using her advantages in machine technology.

During this time of peace, Elysium literature entered its second golden age, led by poets, political theorists, historians, and a few notable playwrights. As literature flourished, a group of patricians (aristocrats) formed a conservative writing club that opposed some of the recent and prior developments in the lingua latina (Latin tongue). In an attempt to encourage traditional spelling and pronunciation, these senators and businessmen bought out several ludi litterarii (elementary schools) operating out of Agusta Elysium around 1572, forcing the teachers to safeguard the future of the imperial language of Latin. At the same time, these reactionaries sought change for Latin, with a stated desire to remove the "impurities" that had settled into the language.

Seeking the patronage of the treasury, the club began to issue pamphlets to other aristocrats, lamenting the corruption of Latin by the vulgar forms spoken by provincials. Indeed, the rise of a vulgar latin (latina truncata) had not gone unnoticed in high society, nor had earlier but less severe bastardizations of the language (i.e. accents and idioms) been ignored. Aristocrats being how they were, many people were supportive of the ideals of the group and it did not take long before the Senate had passed a bill that called for the formation of a societas (institution) devoted to the preservation, purification, and proper evolution of Latin.

In this way, the Societas Latinae (Latin Institute) was founded in 1579 by advice of the Senate. Over its first decade, the Institute brought all of the ludi litterarii in the capital under its wing and created the first permanent elementary school (as other litterarii only operated in gardens, houses, basilicas, temples, or plazas) on a plot of land in the Horti Maecenatis (Gardens of Maecenas) gifted to the Institute by Caesar Fabius. For the time being, this school building and attached library would be the only permanent facility for the Institute, a precursor to its future influence.

Growing in membership, the Institute became an anchor in the development of Latin. Although its direct influence was small at the start, its unflinching persistence in its conception of the language would have a delayed effect on the Latin of city-dwellers but an effect nonetheless. Over time, the Latin of distant cities persistently drifted closer to this one fixed point, at a rate that only rose with the influence of the Institute.

Only the Atomist school countered the worldview of creation, as perhaps the sole non-Religious philosophical school. One of their core beliefs was that ex nihilo nihil fit (nothing comes from nothing) and therefore, whatever exists can be neither created or destroyed, only changed in form. Atoms are what exist and the void is what does not exist - for Epicureans, there was nothing else than atoms moving through the infinite void. By this time, only one philosopher still associated himself with this school of philosophy, the last vestige of a dying position. Dionada of Septimia was how he would be remembered, primarily for his treatise written in 1558 as an attempt to dismantle Aristotelian physics.

De Motu (On Motion) was a brilliant synthesis of geometry and atomism. While Aristotelian physics was in vogue for theorizing about nature, geometricians were the driving force behind the last millennium of advances in machinery. As pioneered by the great Archimedes, geometry alone informed how moving parts could be arranged to instigate motion in a desired direction, often with tremendous precision. Romans understood the principle that an action in one direction would induce motion in that direction and they knew the direction of the actions of ropes, gears, and other machines. Dionada interpreted this geometry of machinery in terms of moving atoms, where motion would be linearly transferred from one atom to another by collision.

Central to his philosophical system was the principle that an atom travels straight unless it collides with another atom. He said that every atom contained a certain amount of conata (efforts) toward one direction, preventing the atom from slowing down or changing direction once in motion (unlike Aristotle who believed that motion required constant action from an effective cause or a teleological cause, for forced and natural motion respectively). When two atoms collided, there was an exchange of conata that resulted in new directions and speeds for the atoms. The final state after a collision depends on the geometry and quantity of the initial conata of the atoms before that collision, such that both the total conata and the sums of conata in every direction had to be preserved. This primitive law of conversation of momentum was motivated by a need to explain how the new motion of atoms would be decided after a collision, since this was the only law which uniquely determined the final motion of the atoms.

In general, the total conata of any object had to be proportional to both its speed and its weight. Some objects could even be heavy enough that nothing else could impart enough conata for noticeable motion - the Earth served as Dionada's example here.

Exchange of conata could be used to explain why every moving object slows down to rest. Atomists considered the atoms in a solid state to be strongly connected such that dislodging atoms was difficult, although not impossible as breaking demonstrates. For this reason, the touching of two solids along a surface - such as a foot on flat rock - imparted conata from the moving foot into the heavy ground (even, as Dionada asserted, if the two surfaces were perfectly flat as he could show with metal plates). When something slides over the ground, it imparts its conata into the atoms of the heavier solid ground - Dionada notes that this is the reason dirt gets kicked up when bolts or stones from siege weapons strike soil.

Contrary to Aristotelians, who argue that air is what causes an arrow to be propelled in flight, Dionada believed that repeated collisions with atoms of air would slowly disperse the conata of the arrow into the air, slowing the projectile down. Similarly, wind would only be an organized motion of atoms in the air, building the conatus of a ship through collisions with its sails. All of these general principles were presented in specific parts of De Motu, as the majority of the text had been devoted to explaining the motion of specific machines with these principles to connect macroscopic motion with the motion of atoms.

Not only did Dionada theorize on collisions between atoms but he also had ideas for how atoms became attached. There were two classes of solid materials in Dionada's theory: elastikos (extensible) and akamptos (inextensible or rigid) solids. Atoms of the former kind were supposedly loosely connected, sharing certain qualities with liquids in being able to change shape, while atoms of the latter were said to be strongly connected, resisting changes to the macroscopic arrangement of the material.

A number of materials were recognized by Dionada as extensible. Most fibers could be stretched - a property that found its use in the simple arcus (bow) which men had known for millennia. Under some contexts, metals could be stretched but they could also be compressed, a process that Dionada described as subject to the same rules as stretching. In particular, Dionada talked about metallic springs, such as the simple leaf springs that had replaced cheaper wooden leaf springs in the suspension of carriages used for the Collegium Itinerarium (Public Transportation Guild), consequently coming into use. Aside from leaf springs, Dionada also described the metallic v-spring used in non-military crossbows to reduce trigger sensitivity. No one before Dionada had described all springs in a single treatise, since a category "spring" had not existed. Dionada did not stop at describing springs, but went as far as to explain their behavior.

When stretched, an extensible material was descrbed as "hav[ing] an inclination toward its natural arrangement", explained by saying that the strength of the connection grew as the material became more extended. Dionada considered connection to be the second kind of interaction between atoms, other than collision. His explanation was that atoms had an innate tendency to joining together with other atoms of the same kind, such that "a great bulk of atoms would pull on other atoms as if by iron rope". This theory of material attraction was how Dionada explained gravity, elasticity, and stickiness. In general, Dionada argued that the strength of atomic attraction increased as clumped together atoms diverged from their natural arrangement (hence, a stretched bowstring would deliver more conata into its arrow the farther it stretches). On the basis of how this broad explanation fits a number of observations, Dionada showed that the strength of an elastic material's inclination to restore its natural shape was proportional to the amount it has presently stretched from its natural position.

A number of other theories are mentioned in passing by Dionada. First, he argued that the Earth is the result of a majority of the atoms in the cosmos ultimately settling into one place by their attractive inclination. Second, he compared the motion of the Sun and stars around the Earth with that of "an arrow that eternally misses its target", saying that celestial bodies were constantly falling toward the Earth (as the heaviest thing in existence) in such a way that they always missed. Third, he explained motion of the wandering stars (planetes) by a "lesser bulk of earth" following the deferent orbit around Earth while the visible star that would follow an epicyclical orbit centered on this mass, even as it also orbited the Earth along the deferent path. Lastly, the rising of fire was explained by a difference in inclination between fire and air, wherein the latter atoms had a stronger attraction that forced the fire atoms out of the way so that "[fire] seems to rise as air falls into its place". Bubbles of air rising through water were taken to follow the same principle, which he further extended as an explanation for the buoyancy of wood in water.

Unfortunately for the development of human knowledge, this book was widely taken to be just another polemic of an Epicurean against Aristotelianism and for this reason, its theories were ignored by most philosophers. De Motu would be the most accurate treatise on physics for some time, presenting a number of primitive ideas that would inspire modern mechanics. One observation, first noticed in De Motu, that would gain a wider audience was the fact that a lodestone bar would always orient itself along the same direction when freely suspended, a discovery Dionada attributed to one of his colleagues.

Since this direction was North-South, Dionada suggested that the lodestone could be used for navigation, by hanging a straight piece of lodestone by a string somewhere on a ship. While no one knows why there are no works on lodestones written by his unnamed colleague (who likely died during the early tenure of Dionada at the Musaeum), Dionada himself commissioned smiths to work pieces of lodestone into bars for selling to merchants coming into Alexandria. Within a century, nearly a fifth of ships in the empire had their own compass (dirigator), mostly ships going to the Erythraean Sea or traveling along the Atlantic coast.

Some nobles and people who spent time at sea started keeping a small dish of water, in which a lodestone was suspended, as a decoration in their home. The household compass made its owner seem to have an interest in travel to far away places and gave the appearance of wanting a constant reminder of the cardinal directions proscribed by Nature.

The reign of Fabius is regarded as the start of a golden age of Elysium mathematics, with mathematicians in the Musaeum and Technaeum renewing their level of discovery after almost three centuries of lacking progress. Dionada likely drew some of the inspiration for his work from this resurgence of mathematics.

The mathematician Aulus Gidius Agris wrote an original treatise in 1545 that detailed both elaborate and simple methods for merchants to work with different types of quantities. There were many other works of this sort written in Italy, Egypt, and Arabia Petraea over the last few centuries but this piece stood above the rest. Among the topics of his Ars Mercatura are: areas of rectangular and irregularly-shaped fields, volumes of solids of various shapes, a pre-algebraic method of double false position for linear interpolation, and a method for extracting roots. Foremost among his original methods was a method of elimination for solving a system of linear equations as an array of numbers. This procedure was the earliest step toward matrices in Western mathematics, discovered independently from its invention in China before 100 BCE.

A commentary written in 1571 on the Ars Mercatura has the first suggestion of negative numbers as a means of replacing some of the awkward terminology used by the original author. In particular, the author of this commentary equated a deficit or a debt with a different sort of number in practice than the positive rational numbers known to mathematics. The same author seems to have annotated a copy of the Arithmetica of Diophantus of Alexandria to note that negative rationals would offer additional solutions to some of his problems, solutions not considered by the famous Alexandrian. Unfortunately, the commentaries would never be published to a wider audience, only receiving occasional attention whenever noticed by scholars working at the Musaeum where they joined the shelves of its library.

Around 1576, the mathematician Aetiales of Lenape published a treatise on trigonometry. For his book, Aetiales invented three new trigonometric relationships between the sides of a triangle and its angles. These relationships were radius (cosine) semichordis (sine), and anteradius (versine), with semichordis defined as the relation of half a chord with half its angle. A number of well-known trigonometric theorems were rewritten in terms of these new relationships, that Aetiales described as more convenient than the chord relationship used by his contemporaries. The image of a circle circumscribing a triangle with these quantities displayed would become ubiquitous for trigonometry from this century onwards.

Applying his own algorithm to a 12,288-sided figure, Aetiales computed a value of 355/113 for the number pi, lamenting that he could go no further. Although this was a landmark achievement for Western mathematics, Aetiales made perhaps his greatest contribution to the empire through his textbook on geometry relevant to contemporary siege engines (a feat that overshadowed the treatise of Dionada, done as it was by a New Platonist who was also the Scholarch (headmaster) of the Technaeum).

Between these major discoveries was the general expansion of the Euclidean system of geometry, with mathematicians adding a number of original theorems about conic sections and triangles. However, these discoveries were characteristic of the same limited progress that had occurred since the writings of Diophantus, with some historians not even including them in their treatment of this period of Roman mathematics.

Astronomy (astronomia) had been the most sophisticated science practiced by Elysium philosophers and mathematicians since the Roman empire conquered Greece. By the 8th century, mathematicians at various institutions in the empire had spent centuries refining the Ptolemaic model of the solar system, although none added to the complexity of the epicyclic orbits of the planets. However, the reign of Fabius is notable for a slow rise in the prominence of astronomical observation in astronomy, where earlier scholars in the field placed the most emphasis on astronomical calculations. This trend accelerated toward the end of the 6th century as newer instruments such as the mariner's astrolabe were being invented.

A famous invention from this period, often considered symbolic of the scientific and artistic golden age that characterized the reign of Fabius, was the Circumspecta Caelesphaerium (literally the Circular Viewing Chamber of the Celestial Sphere). Constructed as a facility for the Musaeum, the 29 meter diameter dome for this structure was completed in 1574. A thin tunnel on the southern end of the dome was the only entrance to the viewing platform within the dome. At the center of the platform was a bronze sphere with a detailed depiction of the known Earth, since the ancient lands of Roman Empire in Europe, too Africa and Asia even North Europa like Escandinavia too Elysium and other lands near the Empire. From the viewing platform, a complete representation of the celestial sphere, including every known star and constellation, was visible, with only a single hemisphere able to be viewed at a time. The implication of this system is that an enormous machine was needed to rotate the celestial sphere around the axis of the entrance tunnel. These mechanisms were robust but their sheer size demanded care from the team of slaves tasked with rotating the entire chamber on the demand of astronomers from the Musaeum.

Not only were stars and their constellations mapped onto the great sphere but a line of gold marked the ecliptic (path of the Sun), with notes along the length of the ecliptic that specified its located across each month. Known to the scholars of the Musaeum as the Ephemeris Magnis (Great Star Chart) or simply the ephemeris, this massive diagram served as the most accurate map of the night sky in the known world, presenting information that was otherwise only available in tables of numbers or in armillary spheres. Directly outside the chamber was a mechanical armillary sphere, with elaborate mechanisms that precisely followed the motions of the Moon and the Sun. Motion of the projected positions of the Sun and Moon coincided with the rotation of a wheel and was designed to follow a mechanical computation of the Enneadecaeteris (also known as the astronomical cycle of Meton). Using this machine, the phases of the Moon could be computed for any day of any year. Unfortunately, the predictions of this device suffered increasing inaccuracy as time passed, forcing its replacement by a machine with updated parameters.

Together, these two devices gave Septimian astronomers an unprecendented capacity to analyze the celestial sphere, paving the way for future advances in the Roman understanding of nature and inspiring thousands of future astronomers. Small replicas of the Ephemeris Magnis began to appear in the homes of astronomers outside of Septimia, with the difference that their chart was etched onto the outer surface of a globe rather than the inner surface of a sphere. By the 8th century, a caelesphaerium was a popular item for navigators, merchants, and the nobility, keeping one in their homes as a sign of worldliness and knowledge to their guests (in a similar manner to the displaying a compass in one's home). With his victories and long, stable reign, Fabius has gone down as one of the most highly regarded emperors in Elysium history, presiding over a golden age in its civilization. This period would serve as a reminder that her strength had not waned, inspiring future emperors to eventually further the glory of Elysium.