Annexing the Iroqueois territory enlarged the empire, with 2,457,066 km² of new territory. Perhaps less than five hundred thousand people remained from the original populace, left behind by the great migration and left alive by the legions that had swept across the land. These tribes would pose a persistent threat to Elysium settlers, raiding their caravans and estates but not daring to attack any coloniae (planned cities built by the state) with their walls and soldiers. With so-called "wild men" everywhere, the wilderness came to be regarded as a distinct boundary of sorts, referred to with the old term limites germanici (German frontiers). Despite the dangers, Elysean people were eager to settle these wild lands, pouring out in the thousands every year.

Before colonists could come, the Senate decreed that all land was ager publicus (public land) - a possession of the state - Land owned by the public accounts could be given to citizens and veterans or worked by employees of the Senate. Another law passed was a promise that every retiring legionary would get a choice: a large plot of rural land or a house in one of the new coloniae. For the next century, this decree would ensure a stable influx of battle-hardened settlers into Iroquois land, creating a strong local citizenry for maintaining control over the region. However, circumstances could change so the law was set to expire after one century, avoiding a possibly unpopular future decision of having to repeal the law.

Retired soldiers could not only handle freely roaming tribes and uncivilized terrain but they were a reliable population for a new territory that would ensure the loyalty of the entire populace. Some would likely spend their later years as auxiliary guardsmen for the coloniae while others would find employment guarding caravans for merchants. By 1455, over three hundred thousand veterans lived in the three provinces of Magnum Lacus, Dacotas and Irocois, mingling with an equal number of citizens that had either come on their own initiative or taken jobs working in public mines, smithies, or lumber mills. To motivate colonists, the Senate had offered citizens an escort to anywhere in the new land where they might manage or operate a public facility for the exploitation of natural resources.

The new provinces was an unspoiled region filled with game for hunting, covered in forests for chopping, and dotted with nodules for mining. At first, only surface veins of ore would be exploited by settlers. As geographic surveys accelerated, Elyseans would establish pit mines on the surface then eventually shaft mines and drift mines for accessing underground nodules found by agrimensores. High on the list of priorities for the Senate was the construction of public highways. Unfortunately, it had no clue what locations would eventually need access to a highway, as cities had yet to grow. For this reason, the Senate satisfied itself for now with laying simple roads built by the legions. Unlike the viae publicae in the civilized world, these roads went around rather than through natural obstacles and were rough paths rather than finely crafted stone walkways. Despite this shortcoming, The new provinces was already poised to be a new industrial heartland of the Empire.

A major downside to the new territory was the difficulty of tilling and planting in the hardy soil. Furthermore, any farm that a citizen established had to be prepared on heavily overgrown land, usually meaning a forest. Extensive plowing was required to prepare the soil to accept domestic grains. Fortunately, farmers had experience with similarly difficult soil and their heavy tools could be brought to bear in colonizing the new territory.

Caesar Aulus Magnum Avitus had devoted nearly the majority of the state's resources to protecting and assimilating all new territories. From a legislative direction, he had claimed all the land in the region for Elysium as ager publicus (public land). Some small claims by a few citizens on the borders were heard and some even granted but nearly every square kilometer of the new provinces was owned by the state. By 1480, nearly a third of the new provinces was exploited sustainably for wood while the rest of the new region consisted either of colonial cities or of private villas for citizens making their living through their own forest, mine, or farm.

The Territory in this era was described as an "uncertain yet lucrative land" for a Elysean citizen. Stories circulated of both great fortunes and great calamities that had befallen colonists. This reputation gave birth to a new style of literature and theater in the form of frontier tales - stories about the hardships and successes of both fictional and historical colonists. One famous play told the story of a lowly actor who set out to work the mines of Magnum Lacus, only to stumble upon a mother lode of silver; a greedy centurion caught wind of his fortune in a small colony then pursued the man with the force of his centuria. Such stories became immensely popular in Augusta Elysium and in the other coloniae of the empire, leaving an indelible mark on Elysium history and culture.

Colonists became regarded as hardy and resourceful people with a penchant for skilled labor. This widespread belief helped create the good reputation of Dacotas, Irocois even Magnus Lacus craftsmen and enticed citizens who fancied themselves that type of person into immigrating. A most recognizable feature of frontier life was the threat of natives bandits and raiding parties. Although most native tribes were expelled in the great clean, over a hundred thousand remained and survived the purge as legions swept through the lands in advance of civilian colonization. With poor Latin and no hope of joining colonies, these tribal communications continued to exist in the public lands for centuries. Many of these people bore general animosity toward Elyseans and would frequently come to blows with citizens working in their plantations, mines, or villas, and merchants traveling on the roads. Sometimes, a villa would disappear off the map, leaving only broken buildings and a signs of struggle and corpses defiled.

Elysium was not idle against this blatant aggression. There were four legions stationed in castra (forts) throughout the territory and tasked with protecting colonists at any cost. At first, defending a territory as large as the provinces was difficult but around 1493 Avitus had reformed the Legion to facilitate the separation of legions into more mobile centuriae that could act as patrol groups to cover as much ground possible. These units occasionally separated further into their contubernia to go from villa to villa in an attempt to keep as informed as possible. A single contubernium was a match for a Tribal raiding party while a century could handle most tribal villages. However, the Native tribes were not entirely unorganized and most were armed with simple weapons, ensuring that even a couple could pose a serious threat to a merchant caravan or family of citizens. Richer colonists met this threat by paying the state for a permanent garrison of legionaries on their lands.

However, the legions could not be everywhere and citizens were forced to come to their own defense on many occasions. A civilian market for military equipment opened to meet this demand, after authorization from the Senate. Three classes of high complexity weapons were used to great effect by colonists. A manuballista was a handheld crossbow, often mounted on a tripod due to its weight, which had an effective range at almost 500 meters. No other weapon could be as accurate at that distance, giving colonists an advantage against bandits. As a relatively inexpensive and portable weapon, the manuballista became known as the quintessential colonial weapon of Elysium- an iconic weapon for a legendary period in Elysium history.

Designs of manuballistae evolved more rapidly after the 5th century, producing a wide variety of designs. Some new designs were sturdier, some lighter, and some longer ranged but massive. One of its main advantages were the sighting elements that were commonly placed in the metal head of the crossbow. Larger weapons of a similar design had a different name due to their size but retained the great range of the manuballista, some even exceeding a range of 600 meters.

Merchants favored varieties of the carroballista, since a heavier but cart-mounted artillery piece could deliver more penetrating blows and at a higher rate of fire than handheld crossbows. By 1500 AUC, most trade caravan had several carroballistae for fending off bandits on the emerging highways. Richer merchants could afford a fusion of the carroballista with a polybolos, the Legion's semi-automatic artillery piece. Feeding ammunition into a vertical funnel, two operators could easily drive the chain belt of one of these weapons fast enough to maintain a rate of 11 bolts each minute. Every shot struck with the force of a heavy crossbow and could be relied upon to incapacitate any lightly-armored attacker. Designs for the polybolos were closely guarded by the Senate so only a couple of dozen workshops were licensed for and capable of its production.

With all the activity, this was an exciting period in Elysium history. Thousands of citizens were starting new lives in a new province, often arriving with free land or a generous subsidy from the state. Despite losing the occasional caravan to Natives tribes, Elysium profited immensely from public mines, plantations, sawmills, stampmills, and other industrial facilities. Profits only grew as the level of infrastructure available in the region was expanded by action of the Senate and the Caesar.

Since mills needed either a river or an aqueduct to supply energy for heavy industry, the state built over a thousand kilometers of aqueducts (aquae) throughout the provincies, connecting cities, mines, and other sites for public industries. Private citizens could only afford access to water for mining by opening a contract for their mine wherein some profits went to the national treasury. More ambitious colonists supplied themselves with water by building simple wood and ceramic aqueducts. More than any other region, the region was highly suited for production on a proto-industrial scale using mechanical hydropower. There was a higher volume of river flow per square kilometer than any place of a similar expanse and the population density was low, allowing this vast supply of water to be devoted toward watermills instead of nourishing cities.

While the first aqueduct was started in 1460, Avitus was primarily concerned with building a network of roads to bring the region into closer contact with Augusta Elysium. His goal required the connection of new cities to the viae publicae princepesque (imperial public highways) that spanned other provinces. Starting work in 1480, architects and engineers used maps of river networks and of existing colonial cities to plan the placement of major highways. For the highways, methods used by the great patron of the interprovincial highway system were copied (as in, they literally plagiarized old records for this project and took credit for the designs in the eyes of the emperor). Despite hundreds of millions of denarii going into construction, the highways did not fully connect all municipia until over a decade after the death of the emperor.

At the same time, three routes for the national postal service (cursus vehicularis) were instituted in region. The mutationes (change stations) and mansiones (rest stations) were far more sparcely supplied than those elsewhere but a message could still be sent from the capitals, to Augusta Elysium in a mere seven days once the roads were done.

The vast wealth of a Empire made these ambitious projects possible but not trivial. The creativity of surveyors, senators, and engineers was heavily strained, even as these experts were drawing heavily from the extensive knowledge that was available to a civilization as ancient and well-recorded as the Roman Empire. In many ways, the challenges of colonizing the territory are viewed as a driving force for the innovations that would arise throughout the 7th century.

Around 1465, a blacksmith in the Civis Virunum began to heat his furnaces beyond the melting point of iron. After a few little accidents, he learned to pour the resulting liquid iron into stone molds for casting. His method for raising the temperature of his bloomery was very tedious, requiring several men to work bellows for a long period of time and seeking to get around this issue, he worked with other craftsmen in Virunum to build a tall furnace which had multiple open ports for cold blasting air into the furnace. Ore was charged through the top with a limestone flux while air entered from the bottom, passing through the material being smelted. Iron would gradually descend through the furnace, coming out in molten form by opening a valve.

As a step forward in ironmaking, this method was really the final stage of about a century of evolution and this blacksmith was far from the first Elysean to heat his iron beyond its melting point - only the first to pour the resulting liquid into moulds. Norica was an iron ore product with exceptional qualities, used by the military for its swords and Lorica Segmentata. However, not all bloomeries in the province of Nova Noricum produced such high quality iron, some were producing low quality iron that would be reforged at a different location into useable iron. This blacksmith who first created a blast furnace had only gone the extra step of melting this low quality iron before reforging and then pouring the liquid iron into casts.

This liquid iron became an extremely low quality iron. Due to its quality and the manner in which it was excreted from a furnace, its Elysean inventor named it ferrum stercum (pig iron). Liquid pig iron could be cast into shapes while removing its impurities. The resulting cast iron was useful for iron kitchenware and farm implements, making its inventor, Titus Albucius Stena, a rich smith. Although Stena soon found that his pig iron was similar to a type of low quality iron forged in some parts of the empire, his addition of casting and blasting methods was unique and were the techniques that earned him fame.

By 1478, Stena accumulated enough wealth to build blast furnaces in other cities, namely Civis Lenape and Nova Toletum Emerita. He ran these other facilities through a guild that he founded, wherein he could appoint people to operate his furnaces in other towns. This expansion was the beginning of a powerful industrial guild in the Elysium Empire. While commissioning forges in Noricum for his reorganization of the Legion, Avitus caught wind of the unique products of the Stena Guild and offered generous incentives for him to expand his smithies. This was the beginning of the most powerful commercial entity that would ever exist - the Elysium Labor Guild.

Avitus too reformed the standard equipment and structure of the Elysean Legions. First, he increased the length of the gladius by 14 cm, improving its effectiveness in individual combat without loss to the ease of stabbing. Similarly, the spatha became the primary weapon for auxiliary soldiers at a length 0.92 meters while the equestrian spatha was redesigned at 1.05 m. Equestrian swords were also rounded more at the tips to prevent sticking inside flesh when running down infantry.

At the time, the standard armor of a legionary was the lorica segmentata. The segmented armor plates on this cuirass were forged from norica in a process which left the core soft to absorb the shock of direct blows - a process known as case hardening. While the plates were unchanged, Avitus replaced bronze components in the armor (e.g. buckles, hinges, tie-rings) with cast iron to reduce costs. These parts could be standardized from casting molds for production en masse for regular orders by the Legion. Although Avitus permanently phased plumbatae (darts) out of the Legion, the pilum (javelin) was still given to every legionary, as their brief volleys in the moments before engaging an enemy were highly effective against barbarian armies.

New regulations assigned one chirurgius legionis (field surgeon) to each centurion, formally enforcing a standard that had been haphazardly employed since the founding of the Septimian Surgical Academy. While field surgeons could tend to the wounds of the troops, assistants were regularly needed to organize the equipment of legionaries, who would be busy building fortifications and digging trenches when their legion made camp. Every contubernium was assigned two servants for loading and unloading equipment from its pack mule. On a march, some timber, food, and cloth would be carried by mule, while the mules of a cohort would pull its mobile brick kiln in turn. When moving in a defensive capacity within the empire, a legion could leave its heaviest equipment back at its station, permitting a faster response time to danger. However, this came at the risk of being incapable of creating fortifications, perhaps in the circumvallation or contravallation of an already entrenched enemy army.

Aside from its civilian support, a cohort once had its own scout cavalry, varying in number according to circumstances, and an accompanying manipulus (division) of heavy cavalry, drawn from the equites of society. Over the last century, the Legion had begun to favor a form of horseman which was even more heavily armored than a legionary, draped from the head of the rider to the legs of the horse in heavy scale armor. These Kataphractoi were made a standard component of the Legion, remaining the main division for citizens above the status of Pleb. There were to be 40 cataphracts for every cohort, i.e. 400 per legion.

Just as the cataphracts were integrated into legions, command over archers and artillery was directly given to the centurions and signiferii of their assigned cohortes. This reorganization involved precise standardization of the number of certain unit types that were allocated to each legion (usually as a specific number assigned to every cohort).

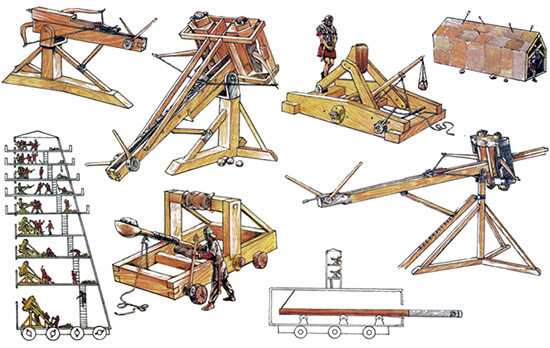

A legion after the military reforms had exactly 1,600 sagittarii (archers), 80 ballistarii (artillery observers), and 200 libratores (gunners). Ballistarii were specialists, trained either at the Academia Bellica in Civis Lenape or taken from legionaries and libratores who apprenticed as "extra credit" with existing artillery observers by assisting in the management of artillery pieces and learning the techniques of artillery spotting and repair. Many legionaries who took upon this role would become a librator, soldiers who did the manual work involved in operating artillery. For now, a full education was a far less prevalent means of learning how to build and operate siege equipment than apprenticeship. In terms of standard siege weapons, each legion under the reform would field 40 polyboloi, 10 mobile carroballistae, and 120 manuballistae. Each weapon needed only one librator to operate once prepared but a number of other gunners were needed to prepare the equipment and assist as needed. At the same time, ballistarii were needed to spot for batteries of artillery and to maintain the equipment during operation. Both members of the artillery corps also had the task of building then operating field-assembled siege engines, a class of artillery pieces that included onagers, rams, siege towers, and heavy ballistae.

In emphasizing the Legion, Avitus reduced the importance of the Auxilia (non-citizen army). Maintenance of auxiliaries along the provincial fortifications was delegated to the government of an imperial province. Each division of border auxiliaries would be under the command of a comes or (count) of the region to which they were assigned. For the most part, the reform was meant to ensure that auxiliaries would no longer see battle far from their station. In this way, Avitus dissolved the tradition of mounted archery in the Elysium army, in favor of more cheap archers who fought on foot.

Elysium needed a more structured and efficient military as an empire that was now firmly rooted in its territory. The professional arm of its military was the Legion, drawing from Elysium's massive number of fit male citizens. Artillerymen came from a similar stock while archers were now also solely citizens. The Auxilia was now functionally a wing of the military consisting of two sections: the Comitana which had town guards employed by the city senate of an urbs at no less than one auxiliary for every 1,000 residents, and the Limitana which consisted solely of border guards or fort contingents employed by a province. As another vital measure, Avitus instituted new standard wages for different positions in the Legion and the Auxilia.

Meanwhile, the classis (navy) was in a sorry state. Caesar had separated the navy from the Legion and renewed its contingent of vessels but there had been few replacements or repairs since his renewal. Most ships were ones built during his reign, although what few new ships were built came straight from the drydocks of Grand Harbour of Lenape and were of a high quality. Avitus had little concern for the strength of the navy because nobody match the Elysium Classis in this new land... y

et. Altogether, Avitus left behind a leaner but stronger military for the empire. Long-term contracts were signed with smithies and woodshops to supplement what could not be produced in industries on public land. With the growing number of public mills and smithies, maintenance costs for the military plummeted by their replacement of private contracts.