You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Electoral Maps III

- Thread starter killertahu22

- Start date

I would imagine a some kind of Tibetan Autonomist Party or Turkestan Islamic Party to win at least a few constituencies in said regionsI've been working on making this map on and off for a veeeeery long time, but finally, here's the most recent National Congress election in my China TL!

*

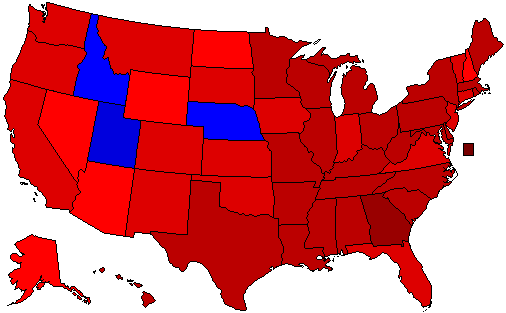

View attachment 624278

China’s history is one of the longest and most storied of any nation in the world, but its current form of government- a democratically elected, federal presidential republic- is shorter than people sometimes remember. It was not until the reforms following the Tiananmen Square Revolution in 1989, in which the Kuomintang government organized a new constitution allowing for party competition, devolution and a democratically elected legislature, that the country’s modern system was officially established, and until 1975, the country was simply a dictatorship with the President of China being entirely unaccountable.

Modern China's politics is perhaps comparable to a strange fusion of the politics of two of Asia’s other most populous and influential countries, India and Japan. The former comparison is evoked due to the heavy federal influence of the governments of each province, and the latter due to China’s significant role in the international technology industry and its dominant party system.

The National Congress, the unicameral legislature of the republic, is a fairly simple institution on its face, with 900 members each elected to single-member districts much like the US House of Representatives every four years (fittingly for the most populous country in the world, the National Congress is one of the largest democratic legislative bodies in the world). Unfortunately, it shares some of that chamber’s faults- malapportionment is common, as is gerrymandering to create majority-minority districts (which packs non-Han Progressive support into smaller areas which they overwhelmingly win), and some have criticized the FPTP system as entrenching the Kuomintang’s support and called for PR to be introduced (particularly the opposition parties). The Kuomintang’s usual defence is to point out that compared to Malaysia or Japan, China’s districts are much more equally sized (each district serves roughly 1.5 million people, and unlike those countries barely any of them are twice or half that size) and great pains are taken by the country's electoral commission not to split counties or prefectures unless absolutely necessary.

Regardless, the status quo is very much to the Kuomintang’s advantage by inflating its legislative majorities (as FPTP tends to do), and the worst it has managed in a National Congress election was falling 8 seats short of an overall majority in 2009. That legislative session was generally agreed to show the weakness of the divided opposition, particularly as the right-wing Economic Liberals simply propped up the government for the most part, and in 2013 the Kuomintang secured over 75% of the National Congress’s seats on 46% of the popular vote, its best ever result, to just 31% and 176 seats for the Progressives.

2017 saw an election dominated by a cooperative display from the Progressives (led by Jiang Jielian) and the Communists (led by Leung Kwok-hung), which had the goal of depriving the Kuomintang of the two-thirds majority that gave it the power to enact constitutional changes (such as repealing term limits to allow Wang Yang to run for and win a third term in 2015) and emphasizing China’s increasing wealth gap. The election saw a big swing away from the Kuomintang, who did indeed lose their two-thirds majority in the National Congress.

Despite this, the National Congress was dominated by the Kuomintang and continues to be so, even factoring in special election losses during the period. With the election of Progressive Jiang Jielian as President, numerous Kuomintang figures in Congress have suggested they will roadblock his agenda, and while electoral reform was a key policy goal of the Progressives it is unclear at present exactly what Jiang will do. Some have suggested he should turn the National Congress into a bicameral legislature with a second chamber elected by PR (akin to what happened in Guangdong after the Kuomintang lost power for the first time), while others in his party have advocated for an overhaul of Congress' electoral system ahead of the 2021 election. With new elections due in October and public opinion on the Kuomintang's obstructionism souring, it seems possible Jiang may choose to hope for an unprecedented Progressive victory in Congress and then implement a new electoral system.

Parties:

Kuomintang: the dominant party of modern China (for the most part), known ideologically since the multi-party era began for small-c conservatism and centrism, and which has used this to pivot to gather voter support at all costs (a little like the PRI in Mexico or Fianna Fáil in Ireland, though like those its star has started to fall). Since 2010, it has been led in the National Congress by businessman-turned-politician Wang Jianlin, who sits for Liaoning’s 15th district (the southern tip of Dalian) and was integral in steering it through the minority government years of the early 2010s. In the 2017 election, they won 40.2% of the popular vote and 574 seats.

Progressive: the strongest opposition party and the main voice of the centre-left in Chinese politics. It mainly draws its support from poorer Chinese voters and ethnic minorities (except in Xinjiang/East Turkestan, where the situation is more complicated), but has always struggled to win enough ground against the Kuomintang to form more than token opposition. Under its National Congress leader and 2020 Presidential election victor Jiang Jielian (who until 2021 sat for Beijing’s 4th district), however, it has started to establish a left-wing populist streak and gather significantly more popular support. The 2017 election saw it win 34.1% of the vote and 280 seats.

Communist: the descendants of the Kuomintang’s old opponents of the 1920s and 30s, they represented only minor insurgent groups until the Tiananmen Square Revolution saw them legalized as a democratic political force. In this form, they’re comparable to the communist parties of India or Japan ideologically, siding with the Progressives on most matters but not really formally for the most part (an exception to this was their decision not to stand in the 2020 Presidential election). Led by Leung Kwok-hung of Guangdong’s 3rd district since 2008, the party won 22 seats and 7.3% of the popular vote in 2017, benefitting from tactical voting agreements with the Progressives.

Loyalist: by some margin the most right-wing party in the National Congress, the Loyalists are led by the populist former newspaper editor Hu Xijin (who presently sits for Tianjin’s 5th district having previously represented Beijing’s 2nd district), and mainly win seats based on personal votes for their populist candidates or by capitalizing on racial tensions from Han voters in regions with a large non-Han population. They won 3.8% of the vote and 9 seats in 2017, 10 seats less than 2013 due to the protest vote campaign by the Progressives and Communists seeking to decapitate as many of them as possible (though the Kuomintang also benefitted from their losses in some seats).

Economic Liberal: a libertarian party currently led by Soong Chu-yu (aka James Soong, the representative for Hunan’s 7th district, based in his hometown of Xiangtan), they effectively sit to the left of the Kuomintang socially and to its right economically. They were traditionally either the third or fourth-biggest party in China, but when they supported the 2009-13 government eagerly in return for concessions like tax cuts, they made themselves enormously unpopular, losing dozens of seats in 2013. They made little recovery in 2017, currently sitting at 6 seats and having won 6.1% of the national popular vote.

Turkestani: the only party representing one of China’s ethnic minorities to have seats in the National Congress, the Turkestani Party supports the rights of the Uyghur majority in Xinjiang/East Turkestan. (Their party's traditional colour is actually the light blue used on the East Turkestan national flag, but the majority map uses purple so as to differentiate them from the Kuomintang.) They vary on whether they are actively pro-independence or merely supportive of civil rights, and on other issues are generally fairly socially conservative and economically leftist. Due to Xinjiang/East Turkestan’s small proportion of China’s population, they only won 0.2% of the national popular vote, but 32.5% of the vote and 6 of its 14 seats (more or less the same as the Progressives won in the province).

Green: as in most countries, the Greens are a fairly simple green politics-focused party. What makes them significant in the context of Chinese politics, of course, is the country’s serious pollution problem. Since 2009, they have held 2 seats- Shaanxi’s 8th district (based in Xianyang, a badly polluted city home to Xi’an’s main airport and several universities) and Hubei’s 37th district (home to Shennongjia Forestry District)- and its leader, Li Hsin Chang (aka Lena Li), sits for the former seat. They took 2.6% of the vote in 2017.

Independents: with the Progressives unseating Tenzin Tethong in Tibet’s 2nd district, the only independent returned to the National Congress in 2017 was Guo Quan, who has represented Jiangsu’s 3rd district (comprising his home district, Gulou in Nanjing) since 2009. Guo originally stood for the 2009 election as a nonpartisan critic of the government’s handling of the Sichuan earthquake, and beat the Kuomintang in a traditionally very safe seat in one of their strongest provinces. In the 2013 and 2017 elections the Progressives stood aside in his favour, allowing him to hold onto a sizeable personal vote. Overall, 4.9% of the vote went to independents and minor parties in 2017, a slight increase from 2013 but significantly less than the peak of 8.3% in 2009.

View attachment 624280

(Here's a version without the majority shading, in case people find that easier to see.)

The latter is what the Turkestani Party is, and Tibet's National Congress districts are so large and rural (and thus difficult to campaign in) that the Progressives basically have an iron grip on them besides occasional strong challenges from independents.I would imagine a some kind of Tibetan Autonomist Party or Turkestan Islamic Party to win at least a few constituencies in said regions

I don’t think any Democrat was doing that well against Nixon in ‘72 unless Watergate was leaked before the election. Jackson would have done a hell of a lot better than McGovern did though, of course.S C O O P '7 2!

What if the January 1980 poll that showed Carter leading Reagan by 29 points ended up being accurate?

James E. "Jimmy" Carter (D-GA)/Walter F. Mondale (D-MN) - 60.39% PV, 525 electoral votes

Ronald W. Reagan (R-CA)/George H.W Bush (R-TX) - 31.39% PV, 13 electoral votes

John B. Anderson (I-IL)/Patrick J. Lucey (I-WI) - 6.61% PV, 0 electoral votes

James E. "Jimmy" Carter (D-GA)/Walter F. Mondale (D-MN) - 60.39% PV, 525 electoral votes

Ronald W. Reagan (R-CA)/George H.W Bush (R-TX) - 31.39% PV, 13 electoral votes

John B. Anderson (I-IL)/Patrick J. Lucey (I-WI) - 6.61% PV, 0 electoral votes

Last edited:

I think Jackson would’ve been conservative enough to carry the Deep SouthS C O O P '7 2!

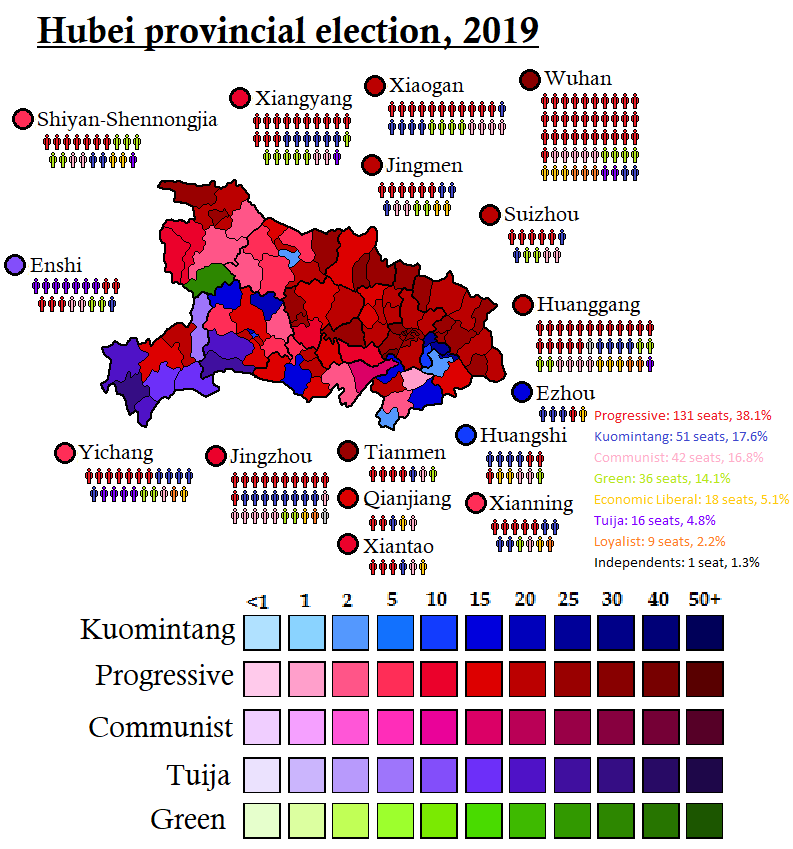

Another China TL provincial election, this one for Hubei.

Hubei is well known as a heartland of the Progressives in the otherwise fiercely Kuomintang region of central China, and the biggest province not to have voted Kuomintang since the Tiananmen Square Revolution. Ever since the republic was founded, it’s been a hotbed of political radicalism- the Wuchang Uprising happened in its capital, Wuhan; in 1927 Wang Jingwei founded a left-wing government there (which Chiang Kai-shek ultimately overthrew); it saw considerable insurgent fighting supported by Zhang Xueliang when Imperial Japanese forces seized some of its eastern territories; and in the 1960s, Wuhan was a hotbed for anti-Chiang groups, which culminated in the Wuhan Incident in 1967, where hundreds of suspected communists were detained on mostly fabricated charges.

Suffice to say, all of this made the Kuomintang very suspicious of Hubei’s people. Government spending was diverted away from it, when the democratic election of the president was introduced voting there was very heavily restricted (the presence of the Tuija and Miao minorities in the west didn’t help), and allegedly Moshan joked in an early 1980s political summit to British PM Margaret Thatcher that he was tempted to turn Wuhan into ‘China’s Liverpool’, and simply allow the anti-government city to be left to collapse.

While Zhao Ziyang was more sympathetic to Hubei once he came to power, activists from Hubei who joined the Tiananmen Square Revolution were some of the most influential in ensuring the new Chinese constitution would promise a federal, not unitary, state. As Qin Yongmin, who later became Hubei’s first Premier, put it, ‘Democracy cannot just be a means to obfuscate injustice in China, but to stop it.’

Qin and his supporters’ helped make Hubei the first province to hold provincial elections (though not the first in China- Beijing and Tianjin elected provincial legislatures in 1989), doing so on the 2nd February 1990. The legislature was elected by STV, with 295 members elected and proportionally assigned to each of Hubei’s prefectures (aside from Shennongjia Forestry District, which elected members in conjunction with Shiyan). While the Progressives have won clear majorities of the vote and of the legislature’s seats in every election, they have never been able to win an overall majority because of this electoral system, which their supporters are quick to point out is a stark contrast from how the Kuomintang have never won an overall majority of the vote for the National Congress or most of the provinces they control despite frequently winning majorities of seats in those legislatures.

Nevertheless, the Progressives have managed to use their control of the province’s government to very productive ends. In Qin’s decade as Premier alone, the Hubei government pumped massive amounts of infrastructure spending into Wuhan, provided legislative protection for the right of workers to unionize and strike if democratic ballots were held, introduced single-payer universal healthcare almost a year before President Zhao rolled it out in the rest of the country, established the concept of the provincial flag by establishing the old flag of the Hubei Military Government as the province’s flag in October 1991 (the 80th anniversary of the start of the Wuchang Uprising), adopted one of the highest minimum wages in China and increased the legislature’s term from three to four years in 1999.

In a way, Hubei is sometimes considered an anomaly in Chinese politics akin to California in the US or Kerala in India, in that its political norm is significantly to the country’s left. This has continued under subsequent Progressive provincial governments, which have established legal protections for Tuija and Miao groups (under pressure from the Tuija Party, which supports affirmative action for the province’s minorities, but particularly the Tuija), protection from discrimination for LGBTQ people and legal recognition of gay and lesbian marriage and transgender identity.

It hasn’t all been plain sailing for the Progressives, particularly after the 2011 election saw them ousted by a rainbow coalition led by the Kuomintang’s Chen Quanguo, which sought to reform Hubei’s economy to make it ‘more appealing to businesses’. However, in a way this spell out of power was very much to the Progressives’ benefit, as they had been slowly losing support from the left to the Communists, Greens and Tuija Party, and the latter two, the Economic Liberals and the Loyalists backing this government’s agenda was seen as a massive betrayal.

Unsurprisingly, 2015 saw the Progressives hoover up support from the smaller parties and kick out enough Kuomintang and Economic Liberal members (the latter of which lost almost all their seats) to return to power as a minority government. While new Premier Zhou Xianwang was hardly seen as the most charismatic figure, he did promise to abandon the Kuomintang’s reforms, and once he came to power, he did just that.

The 2019 election was something of a return to normalcy for the province’s politics, as the Greens and Tuija Party distanced themselves from the failed Chen government and switched back to sniping at Zhou for corruption allegations and consequently picked up seats, while the Economic Liberals slightly recovered. The Progressives were yet again forced to rely on a minority government with support from the minor parties to get back into power, though.

Of course, since the election was held back in February 2019, Hubei has been a centre of attention for all the wrong reasons thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic breaking out in Wuhan. At first, this seemed like it might completely change the face of the province’s politics, particularly as Zhou’s response to the crisis was badly botched and did little to contain the virus’s spread. However, after meeting with Jiang Jielian and being convinced to stand down (he was later appointed to a minor role in Jiang’s cabinet, which it has become clear was the reward for his resignation), Zhou’s successor, Li Tie, worked to alleviate the suffering of Hubei’s people in lockdown, such as by expanding the province’s welfare provisions, calling for housing to be recognized as a human right and increasing the minimum wage. These measures have revitalized the Progressives’ popularity, and barring another major catastrophe, it seems likely they will win in 2023 with ease.

*

Chinese provincial/city council election maps

Beijing

Guangdong

Chongqing

Shaanxi

Inner Mongolia

Shanxi

Tibet

Qinghai

Xinjiang/East Turkestan referendum

Fujian

Hubei is well known as a heartland of the Progressives in the otherwise fiercely Kuomintang region of central China, and the biggest province not to have voted Kuomintang since the Tiananmen Square Revolution. Ever since the republic was founded, it’s been a hotbed of political radicalism- the Wuchang Uprising happened in its capital, Wuhan; in 1927 Wang Jingwei founded a left-wing government there (which Chiang Kai-shek ultimately overthrew); it saw considerable insurgent fighting supported by Zhang Xueliang when Imperial Japanese forces seized some of its eastern territories; and in the 1960s, Wuhan was a hotbed for anti-Chiang groups, which culminated in the Wuhan Incident in 1967, where hundreds of suspected communists were detained on mostly fabricated charges.

Suffice to say, all of this made the Kuomintang very suspicious of Hubei’s people. Government spending was diverted away from it, when the democratic election of the president was introduced voting there was very heavily restricted (the presence of the Tuija and Miao minorities in the west didn’t help), and allegedly Moshan joked in an early 1980s political summit to British PM Margaret Thatcher that he was tempted to turn Wuhan into ‘China’s Liverpool’, and simply allow the anti-government city to be left to collapse.

While Zhao Ziyang was more sympathetic to Hubei once he came to power, activists from Hubei who joined the Tiananmen Square Revolution were some of the most influential in ensuring the new Chinese constitution would promise a federal, not unitary, state. As Qin Yongmin, who later became Hubei’s first Premier, put it, ‘Democracy cannot just be a means to obfuscate injustice in China, but to stop it.’

Qin and his supporters’ helped make Hubei the first province to hold provincial elections (though not the first in China- Beijing and Tianjin elected provincial legislatures in 1989), doing so on the 2nd February 1990. The legislature was elected by STV, with 295 members elected and proportionally assigned to each of Hubei’s prefectures (aside from Shennongjia Forestry District, which elected members in conjunction with Shiyan). While the Progressives have won clear majorities of the vote and of the legislature’s seats in every election, they have never been able to win an overall majority because of this electoral system, which their supporters are quick to point out is a stark contrast from how the Kuomintang have never won an overall majority of the vote for the National Congress or most of the provinces they control despite frequently winning majorities of seats in those legislatures.

Nevertheless, the Progressives have managed to use their control of the province’s government to very productive ends. In Qin’s decade as Premier alone, the Hubei government pumped massive amounts of infrastructure spending into Wuhan, provided legislative protection for the right of workers to unionize and strike if democratic ballots were held, introduced single-payer universal healthcare almost a year before President Zhao rolled it out in the rest of the country, established the concept of the provincial flag by establishing the old flag of the Hubei Military Government as the province’s flag in October 1991 (the 80th anniversary of the start of the Wuchang Uprising), adopted one of the highest minimum wages in China and increased the legislature’s term from three to four years in 1999.

In a way, Hubei is sometimes considered an anomaly in Chinese politics akin to California in the US or Kerala in India, in that its political norm is significantly to the country’s left. This has continued under subsequent Progressive provincial governments, which have established legal protections for Tuija and Miao groups (under pressure from the Tuija Party, which supports affirmative action for the province’s minorities, but particularly the Tuija), protection from discrimination for LGBTQ people and legal recognition of gay and lesbian marriage and transgender identity.

It hasn’t all been plain sailing for the Progressives, particularly after the 2011 election saw them ousted by a rainbow coalition led by the Kuomintang’s Chen Quanguo, which sought to reform Hubei’s economy to make it ‘more appealing to businesses’. However, in a way this spell out of power was very much to the Progressives’ benefit, as they had been slowly losing support from the left to the Communists, Greens and Tuija Party, and the latter two, the Economic Liberals and the Loyalists backing this government’s agenda was seen as a massive betrayal.

Unsurprisingly, 2015 saw the Progressives hoover up support from the smaller parties and kick out enough Kuomintang and Economic Liberal members (the latter of which lost almost all their seats) to return to power as a minority government. While new Premier Zhou Xianwang was hardly seen as the most charismatic figure, he did promise to abandon the Kuomintang’s reforms, and once he came to power, he did just that.

The 2019 election was something of a return to normalcy for the province’s politics, as the Greens and Tuija Party distanced themselves from the failed Chen government and switched back to sniping at Zhou for corruption allegations and consequently picked up seats, while the Economic Liberals slightly recovered. The Progressives were yet again forced to rely on a minority government with support from the minor parties to get back into power, though.

Of course, since the election was held back in February 2019, Hubei has been a centre of attention for all the wrong reasons thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic breaking out in Wuhan. At first, this seemed like it might completely change the face of the province’s politics, particularly as Zhou’s response to the crisis was badly botched and did little to contain the virus’s spread. However, after meeting with Jiang Jielian and being convinced to stand down (he was later appointed to a minor role in Jiang’s cabinet, which it has become clear was the reward for his resignation), Zhou’s successor, Li Tie, worked to alleviate the suffering of Hubei’s people in lockdown, such as by expanding the province’s welfare provisions, calling for housing to be recognized as a human right and increasing the minimum wage. These measures have revitalized the Progressives’ popularity, and barring another major catastrophe, it seems likely they will win in 2023 with ease.

*

Chinese provincial/city council election maps

Beijing

Guangdong

Chongqing

Shaanxi

Inner Mongolia

Shanxi

Tibet

Qinghai

Xinjiang/East Turkestan referendum

Fujian

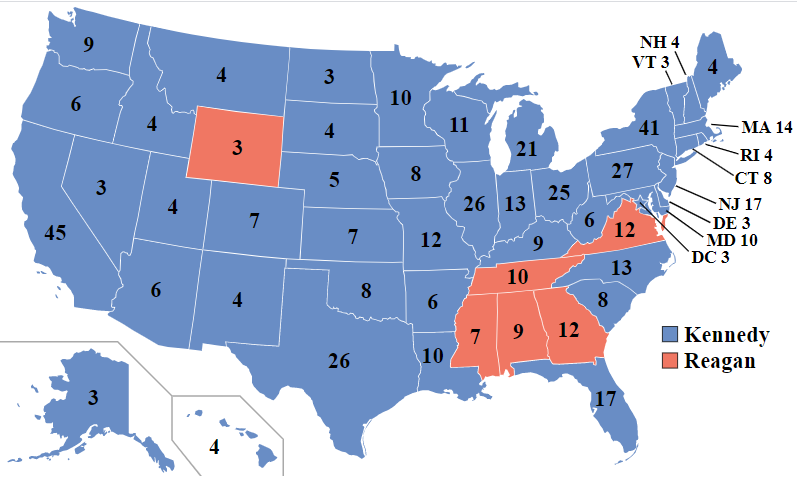

No Chappaquiddick and Nixon Tried, the Fight to Restore Trust in the Government in 1976

Last edited:

'72, '76 or '80?No Chappaquiddick and Nixon Tried, the Fight to Restore Trust in the Government

View attachment 628619

Oh crap forgot to put the year. 1976.'72, '76 or '80?

Who's the incumbent here, Ford?Oh crap forgot to put the year. 1976.

Yep. Despite Ford not pardoning Nixon he still gets challenged by Reagan and this time loses.Who's the incumbent here, Ford?

Why would Kennedy lose West Virginia?No Chappaquiddick and Nixon Tried, the Fight to Restore Trust in the Government in 1976

View attachment 628619

Yeah, now that you point it out, that is illogical...Why would Kennedy lose West Virginia?

Yeah looking at it now doesn’t make much sense. I’ll change that.Why would Kennedy lose West Virginia?

Why would Kennedy lose West Virginia, but win the Carolinas, Florida, Louisiana, and Arkansas against “State Rights” Reagan?No Chappaquiddick and Nixon Tried, the Fight to Restore Trust in the Government in 1976

View attachment 628619

Sadly, his populism was not heroic enough to win the neighboring state of Kentucky, which Kerry still loses by 6 points under this uniform swing

But never fear, ancestral Dems, because our hero wins the ancestral blue dog Democrat stronghold of Arkansas by a solid 4-point margin in this very same scenario!

Share: