A great sense of hopelessness seemed to grip the North as the month of August 1864 started. The campaigns of July had racked up horrifyingly high casualties, and yet no important Confederate city had been taken, and no fatal blow had been dealt against the enemy. Although Republican newspapers tried to keep up their spirits, Northerners could scarcely believe that victory was nigh when they contemplated endless lists of casualties and hospitals brimming with the dead and wounded. As the elections drew closer so did the danger that the people would not re-elect Lincoln. Exhilarated Chesnuts contemplated electoral victory, preparing to hold a convention towards the end of August calling for an “honorable peace”. At the same time, the new fortunes of the Copperheads reinvigorated Southern spirits and inspired them to maintain their defiance. The “friends of peace at the North”, General Lee believed, were at the cusp of success. But this success, the

Richmond Enquirer recognized, could only be secured “by the continued exertions of our own Peace party, which we call the Army of Northern Virginia.” Defeating the Copperheads necessarily required defeating the rebels on the field, but sanguine expectations were giving way to despair. “Why don’t Grant, Thomas and Sherman do something?”, asked a despondent George Templeton Strong, echoing the thoughts of thousands of Union men.

While Grant definitely intended to do something, his plans were more than once derailed by the competence of his foes and, sadly more commonly, the ineptitude of his subordinates. The most salient example was yet another failure on the part of Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. Ordered to advance at the same moment as the Army of the Susquehanna marched forth, Sigel had been moving towards Staunton, “from where Lee’s army received some of its meager supplies”. On July 2nd, the same day the Union was being driven out of Ashland, a scrapped together force of 5,000 rebels attacked Sigel at New Market. The ensuing battle proved a moment of special pride for President Breckinridge, for the Kentucky “Orphan Brigade” that he had helped to raise, which included his son Clifton, performed admirably. Another addition to Southern legend was the charge of 247 cadets of the Virginia Military Institute, aged 15 to 17, even if this would later become a sad forerunner of more extensive, and desperate, recruitment of children into the Confederate Army. However, rather than a rebel victory this was a Federal defeat, for Sigel had only showed his “skill at retreating”, in the caustic words of James McPherson. Sigel’s campaign then slowed to a crawl.

Aside from Sigel, Grant still had to deal with General Hancock. The relation between the General in-chief and the commander of the Army of the Susquehanna had only become frostier with time, but Grant still tried to support Hancock. Anxious over the lack of progress in the current position, Grant insisted that Hancock continue the campaign by swinging south to Petersburg. However, Hancock instead pinned his hopes in a new scheme. Continuing the desperate fighting thus far seen by moving to Petersburg would not yield any results, Hancock believed. But if Lee could be forced out of Cold Harbor, then the road to Richmond and an open fight would be clear. Hancock’s plan rested on the idea offered by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Clay Pleasants, a former Pennsylvania engineer that proposed to dig a tunnel below Lee’s lines, planting a mine, and blowing it up. “We could blow those damn lines out of existence if we could run a mine shaft under it”, said Pleasants. Grant endorsed the plan, being reminded of a scheme he had considered in Vicksburg if he had been forced to laid siege.

Pleasants and his regiment, mostly formed out of coal miners, managed to build a 500-feet tunnel across no-man’s-land, surprising the military engineers that had believed any tunnel over 400-feet impossible due to ventilation problems. Showing Yankee ingenuity, Pleasants had used fires to warm air and force it to circulate through the mine. To assure success, Hancock sent Meade in an expedition to the Bermuda Hundred Peninsula, to hopefully distract Lee by threatening the Richmond-Petersburg railroad. In hindsight, Grant bitterly regretted that this was merely a distraction, for Meade actually had no effective resistance in his front and could have taken Richmond or Petersburg if he had had enough support. Indeed, the move so alarmed Breckinridge that he directly ordered troops into the area to stop Meade, whose presence had already disrupted the supplies advancing to Lee’s lines. Advancing cautiously due to his small numbers, Meade only tore up some rails before being chased back by Confederate troops under Stonewall Jackson, who then trapped him by constructing the fortified Hewitt Line. Meade’s chief engineer lamented how “the enemy had corked the bottle and with a small force could hold the cork in its place.” The Bermuda Hundred expedition did afford the Union a foothold that would help them in future campaigns, and it succeeded in drawing troops away from Lee’s lines, but, years later, Grant would count it as a lost opportunity and argue that the mine was merely something to keep the men busy, similarly to his own quixotic schemes before the Second Vicksburg Campaign.

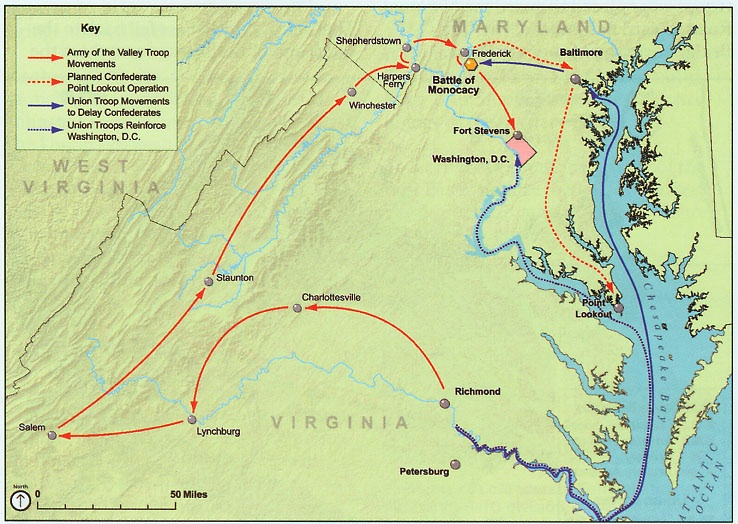

The digging continued for the last weeks of July, meaning that Hancock’s Army remained in place while the impatience of the Northern people and press just grew. By July 20th, preparations continued, but a new threat was appearing in the Valley. The retreat of Stonewall Jackson towards the Bermuda Hundred had allotted Sigel an opportunity to strike against Lynchburg, a logistical center from where he could threaten Richmond. Under the constant depredations of guerrillas, Sigel’s men had grown hungry and less than battle-ready, and were consequently turned away from Lynchburg’s fortified walls. When a larger force under General Jubal Early arrived, a panicked Sigel retreated towards the mountains of West Virginia, unwilling to either face Early at his front or the guerrillas at his rear. Sigel would later explain that he would have faced certain destruction at the hands of the enemy had he tried to give battle, and that might have been true, but the shameful maneuver left the road towards the North open. Early and his men, decided to match Jackson’s previous campaigns, lessen the pressure on Lee, and “remind the Yankees of their vulnerability”, crossed into Maryland. The move would not be detected until the Harpers Ferry garrison saw Early marching north, having contently believed that he and his rebels had returned to Lee.

Upon receiving the news, Grant immediately ordered Hancock to dispatch troops and stop Early, conscious of the disastrous effect a Confederate Army running amok could have in the people’s morale. But Hancock hesitated. Mistaken intelligence seemed to show that most of Early’s corps remained on his front, and Hancock thus believed that sending an entire corps north would be playing right into Lee’s hands. Pleasant’s mine was also almost complete, and if the Army was weakened right before the attack their odds of victory could be lessened. As a result, Hancock offered merely one division, instead of the corps Grant had requested. Grant sharply replied that “putting an end to incursions north of the Potomac” was of the utmost urgency, but this struck Hancock as arrogant lecturing. Precious time was lost as the generals traded increasingly frustrated telegrams, before Hancock finally acquiesced and sent his cavalry north. But the delay had allowed Early to swept aside the Harpers Ferry garrison and reach Frederick, the center of Maryland Unionism.

At the start of the year, Frederick had been the scene of a large guerrilla action, when groups of outlaws tried to stop the counting of the ballots for the constitutional referendum. Holding the “bayonet constitution” to be inherently illegitimate, the guerrillas had hoped to disarrange the process enough to force another election, giving the Confederate Army enough time to retake the state. The Federal Army, its presence in Maryland strengthened by Lincoln’s decree, was able to beat back the insurrection, and several of the ring leaders were executed by military court. Even Northern moderates coolly approved of the crackdown as the only way to maintain law and order in the state; Confederates, for their part, claimed the riot was nothing but an excuse trumped up by “the reckless and unprincipled tyrant” to justify “acts of violence and outrage too shocking and revolting to humanity to be enumerated”. These acts, the commanders reminded their men, had been celebrated by the Unionists of Frederick, the same ones that had turned their backs on Lee when he had invaded the previous year. Moved by such declarations, and because most of the Yankee troops had left for the frontlines, Early’s soldiers plundered and torched Frederick. “The most of the soldiers seem to harbor a terrific spirit of revenge and steal and pillage in the most sinful manner”, observed a South Carolinian. “But I suppose this is just payment for the hunger and homelessness that the Yankees cause”.

Panic surged thorough Maryland and Pennsylvania, which grimly remembered the trail of destruction Lee had traced in his last campaign. The seriousness of the raid had been at first dismissed by both Grant and Stanton, but as Early’s march continued and Waynesboro and Fairfield were added to the list of burnt towns, his threat increased. The rebel commander released a proclamation similar to the ones previously issued by Bragg and Price that called for the Maryland guerrillas to join his march. The proclamation was mostly meant for the guerrillas that had rallied around John Singleton Mosby, a former Virginia lawyer that had become so feared and so slippery a raider that he was dubbed the “Gray Ghost”. Leading a relatively small band of 1000 irregulars, Mosby nonetheless started a thorough reign of terror that saw isolated outposts and wagon trains plundered, and freedmen and soldiers on furlough murdered in cold blood. Mosby’s control was so extensive that entire counties became known as “Mosby’s Confederacy”, for no supplies or men could move there unless under heavy guard. The situation was so critical that Grant had issued an order to hang Mosby’s men on sight.

Although the

Richmond Dispatch exulted the “greatly strengthened feeling in our favor” and the “gallant Marylanders” who flocked to Early’s banner because of the proclamation, in truth few joined the Confederate ranks. Probably most were keenly aware that Early’s campaign could be nothing but an extended raid, with long-term or permanent occupation of the State by the Confederate Army out of the question. Possibly, some remembered how Price’s and Bragg’s proclamations had been followed by disastrous defeats, and wanted first to see if Early could achieve a decisive victory. The proclamation nonetheless increased the Yankees’ hysteria. “There is folly or incompetence somewhere in our military administration”, mildly observed a newspaper, while a furious Montgomery Blair, who had had a house burned by Early’s rebels, bitterly rallied against the “poltroons and buffoons” in the Army and demanded action. Even Lincoln had become alarmed by the movement. To handle the administrative tasks that had bogged him down, Grant appointed General E.R.S. Canby as his chief of staff and managed to scrape together a hodgepodge force of 17,000 men, whom he rushed to Gettysburg, the little crossroads town where Reynolds had once dealt another blow to Lee after Union Mills. Early had approached it again because there were rumors that it had abundant shoes that his troops and their bleeding feet would appreciate.

On command of the motley Union force that day was Benjamin Butler. Due to both his military shortcomings and his shifty nature, Butler had never obtained a large command, being instead the leader of the occupation troops in Maryland since almost the start of the war. His powerful political connections had been both maintained and enhanced by his growing commitment to Radicalism, shown in his iron-fisted administration and his embrace of confiscation and Black suffrage. After Lee had been beaten back, Butler had ruthlessly confiscated the properties of the planters that had been friendly to the invading rebels, and then had used the Army to maintain order during the tumultuous and revolutionary constitutional process. This spurned some Radicals into considering Butler a possible presidential candidate, and the General naturally adopted these ambitions immediately. As a result, Early’s invasion was not a setback, but an opportunity to obtain the glory that had eluded Butler thus far. Encouraged by Jayhawker partisans that pronounced Early’s rebels a “dirty, shoeless, hungry, exhausted, unsavory lot”, Butler disregarded Grant’s orders to wait for all reinforcements and struck the Confederate vanguard on August 6th. Apparent initial success quickly gave way to disaster as Early concentrated his force and almost drove Butler out of Gettysburg.

The arrival of Grant’s reinforcements managed to stop the Confederate attack, by sheer force of numbers, for the majority of the bluecoats were green soldiers and militia. Nonetheless, the “bulldog spirit” of the Yankees, together with their advantage in terrain, held back Early. When Hancock’s more experienced reinforcements were finally spotted, Early retreated towards the Valley. A sedate Sigel had done little in the meantime, merely trying to gather supplies but finding that Early or the guerrillas had already taken most of them. His retreat into West Virginia had allowed him to feed his men, but they were still reluctant to try and face Early despite Grant’s orders to cut off the rebels’ retreat route. A nominal effort was quickly abandoned, and much to Grant’s consternation Early returned to Virginia, boasting of humiliating the Yankees. And he was not wrong, for aside from inflicting 1,700 casualties at the price of 900, Early had also obtained a plentiful bounty and stricken terror into Maryland and Pennsylvania, a “most-welcome development after the actions of those people in Mississippi and Louisiana”, Lee noted. “We haven’t taken Philadelphia or Harrisburg,” Early concluded brightly, “but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell”.

Hancock had mostly ignored Early because his cherished mine scheme seemed increasingly promising. Even some rebels had started to get nervous. Although their engineers, like their Yankee counterparts, believed that such a long tunnel was impossible, by the first week of August they had started to hear the “dull, faint sounds of digging and movement in the earth below them.” Just in case, a second line of defense was built and some efforts at countermining started. Alarmed that the plan could come to naught, and following Early’s raid, Hancock and Pleasants decided to blow the mine at once. Over 8,000 pounds of gunpowder were loaded and detonated at the dawn of August 14th, creating an enormous mushroom cloud, “full of red flames, and carried on a bed of lightning flashes, mounted towards heaven with a detonation of thunder.” Several rebels were flung into the air, others were buried by the dust and rocks thrown up by the explosion, “some with their legs kicking in the air, some with the arms only exposed, and some with every bone in their bodies apparently broken.” Despite the gory results of the explosion, the follow-up attack was not what Hancock had expected. His men went

into the crater, instead of around it, which resulted in a disorganized assault that allowed the rebels to fire down on them. “The shouting, screaming, and cheering,” wrote Horace Porter, “mingled with the roar of the artillery and the explosion of shells, created a perfect pandemonium . . . the crater had become a caldron of hell.”

Around the Crater, Lee’s soldiers remained organized enough to repeal Hancock’s attacks, and even those who managed to push through the Crater found Lee’s intact second line, which the tired Yankees that had barely made it through could hardly overcome. Soon enough, Hancock yielded to the futility of further fighting and ordered a retreat. The Confederates kept up the pressure, sending a storm of bullets that “screeched and screamed like fiends” and artillery that “ploughed and tore up the ground”. Many blue troops left behind were subjected to a sadistic “turkey shoot”, greatly increasing the fatalities. Black regiments suffered especially, for the Confederates showed accustomed but still horrific brutality. “They threw down their arms in surrender”, a Confederate colonel remembered, “but were not allowed to do so . . . This was perfectly right, as a matter of policy”, and had “a splendid effect on our men”. A horrified Grant read the reports, and after a long moment in mournful silence remarked sullenly that the Crater “was the saddest affair I have witnessed in the war. Such an opportunity for carrying a fortified line I have never seen, and never expect to see again.” In the frontlines, bitter recriminations followed as Hancock and his commanders could not agree on whom to rest to blame, and grievously regretted that the work of several weeks had resulted in nothing but 4,000 Federal casualties to a paltry 1,600 rebel losses.

The infamous Battle of the Crater thus joined Cold Harbor in Northern minds as another example of senseless slaughter resulting from the ineptitude of the Union leaders. James McPherson concludes that the Crater “In conception bid fair to become the most brilliant stroke of the war; in execution it became a tragic fiasco”. The crisis in Northern morale deepened as an inevitable result, and the once high support for Lincoln and Grant seemed to evaporate. A Copperhead declared that Grant could never again “go into a town or village in the whole North where his name will not excite horror in the breasts of numberless widows and orphans”, and even First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln pronounced Grant a “butcher” and “not fit to be at the head of an army”. Charles A. Dana, who was otherwise usually friendly to Grant, called the latest events a “black and revolting dishonor”, the result of “poltroonery and stupidity”. The reports of the failure fed the Copperhead narratives that Lincoln was an incompetent tyrant and Grant a cold butcher. Many even reported falsely that the Black troops were the cause of the failure. This at the same time as 1,500 captured Union soldiers, including at least 500 Black men, “were paraded through Petersburg, to the delight of jeering crowds who hurled epithets at them; the white prisoners were sent off to prison camps and the black ones sold into bondage”, as related by Elizabeth R. Varon.

The twin failures at the Valley and the Crater demanded new measures be taken. Grant was finally able to prevail upon Lincoln and obtain Sigel’s removal, for, as Grant acridly remarked, Sigel would “do nothing but run; he never did anything else”. Only the fact that Lincoln was still wary of antagonizing German Republicans kept Sigel from being hauled before the Senate Committee on the Conduct of War, but he would never command Union troops again and had his reputation destroyed. As for Hancock, Grant expedited a general order moving his headquarters to the field and making it clear that the Army of the Susquehanna would now be under his direct and constant strategic direction. Though Hancock would remain, at least officially, in tactical command, the simple fact was that Grant had lost his faith in the “Thunderbolt”, a man that hadn’t shown the daring or the speed that his nickname seemed to describe. Enormously embittered, and peeved by the continuous attacks of the press, Hancock resisted Grant’s new orders. Hancock was also being besieged on his political front, for many Republicans laid the entire blame on his shoulders, to protect Lincoln, while also criticizing his conservatism. This at the same time as many Chesnuts courted him in an effort to add an unimpeachably loyal military man to their ranks. Lincoln and Grant both were aghast at Hancock’s behavior, believing him corrupted by political ambition, an ironic twist when he had been selected justly because he had seemed to be as staunchly apolitical as Reynolds.

The breaking point came when Grant arrived at the Army of the Susquehanna’s headquarters on August 20th. Grant had requested a meeting with Hancock to lay down the new plans, which finally contemplated the march to Petersburg that Grant had long wished to execute. Instead of complying, Hancock commandeered an ambulance and rode it to the front to oversee a rather meaningless skirmish. A dumbfounded Grant could scarcely believe what he was hearing, while the ever-loyal Rawlins exploded in fury. According to James H. Wilson, Rawlins “grew pale, and his form became almost convulsed with anger” as he exclaimed that Hancock ought to be court-martialed for this disrespect. Rawlins surely was reduced to apoplectics when a message then came, informing them that Hancock was taking a medical leave because his wounds were still bothering him. Grant had had enough. On August 22nd, he obtained Lincoln’s approval to remove Hancock from command, appointing General John Sedgwick in his place.

For all intents and purposes, Grant was now the one leading the Army of the Susquehanna, both in strategic and tactical matters. For those who had been disappointed by how Grant had stayed in Philadelphia instead of right on the frontlines, the change was reason enough to celebrate and look forward to the next campaign. “Grant has more faith in square face to face fighting than in strategy,” the

Chicago Tribune declared. “It is Grant’s lion heart that wins.” Grant did indeed have immense valor, but unlike what the newspaper claimed he also had a keen strategic mind, and soon enough the preparations were almost complete for a stroke that would push Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia to the breaking point. “I never before saw Grant so intensely anxious to do something,” a staff member wrote. But Grant recognized that the fate of this new campaign was intimately linked to the campaigns in the other theaters of war. The Western campaigns were second in importance only to the Virginia campaign in Northern eyes. “Success of either one depends on the other,” the

New York Herald acutely observed. Consequently, even as he moved to the frontlines in Virginia, Grant kept a close eye in Thomas’ siege of Atlanta and Sherman’s drive for Mobile. If the Federals triumphed in any of those three fronts, the Ohio soldier Samuel Evans said, then “the Rebellion must fall”. However, the Union needed a victory soon, before the election could sweep a Copperhead into office. “Whether the thing ‘can be slid,’ this season, is the great problem”, Evans continued. “May the God of Battles grant us a favorable solution,

hastily.”

“The god of battles did not oblige”, writes Elizabeth R. Varon simply. The maneuvers of the previous month had allowed Thomas to get to the gates of Atlanta, where his 71,000 strong Army of the Cumberland was trying to force Cheatham’s Confederates out. His attempts to force Thomas back having failed, Cheatham found himself in a precarious position. He had managed to concentrate around 47,000 effectives to defend Atlanta, after pressing even cooks and clerks into the frontlines. Sherman’s march through Alabama had reduced his supplies, and Thomas had cut his line with Richmond, but Atlanta could still be fed by a single line that connected it to Macon. Knowing that this line was Cheatham’s only source of supplies, Thomas had started to focus on cutting it off. But Thomas’ logistics were similarly vulnerable, for his entire Army was fed by the Western & Atlantic Railroad that came from Chattanooga. This allowed the Confederate cavalry under Joseph Wheeler to strike Thomas’ exposed lifeline. The siege of Atlanta had then become a series of raids and counterraids, as Thomas slowly extended his lines around the city while Cheatham discounted suggestions to attack after his previous setback. Instead, he returned to a purely defensive strategy, which allowed him to stop Thomas’ cautious advance at the battles of Ezra Church on August 1st, and Utoy Creek on August 8th.

Neither Lincoln nor Breckinridge were pleased with how the campaign was developing. Lincoln because he knew the Union could not afford the time needed for a lengthy siege; Breckinridge because he knew the Confederacy hardly had the necessary resources. Voices in Richmond were already demanding that Thomas be driven back, while in Philadelphia many wished for a more aggressive strategy. A still disgruntled Stanton told Thomas that his plan seemed like “the McClellan strategy of do nothing and let the rebels raid the country”. Breckinridge was gentler in his communications, but he still exerted some pressure on Cheatham and worried over whether a long siege could be resisted. The Confederate President was well-aware that many Southerners were pining their hopes into a successful defense of Atlanta, so much that a defeat would crush their morale. "Atlanta is now felt to be safe, and Georgia will soon be free from the foe”, declared confident rebel newspapers. “Everything seems to have changed in that State from the deepest despondency.” Buoyed by the “cheering” news from Georgia, a War Department clerk even went as far as predicting that “Thomas’ army is doomed”. But Breckinridge probably was closer in opinion with Mary Chesnut, who wrote in her diary that “our all depends on that Army at Atlanta. If that fails us, the game is up.”

Soldiers from both sides struggled to maintain the game despite the degenerating conditions in the trenches. The men experienced a preview of the early 20th century wars, enduring cramped trenches filled with mud, refuse, and even corpses. Both Yankees and Rebs suffered from the poor conditions, which strained them not only physically but psychologically as well. Describing life in the Atlanta trenches, a Union colonel wrote that if “the sun don’t beat down in red-hot rays . . . it rains in fearful torrents, and the ditches [trenches] in which they lie fill with water . . . covered with mud, ticks, body lice”. But the soldiers had to remain hidden in the filth, for if they “lift their heads six inches from the ground a sharp shooter sends a ball whizzing through their brains”. The constant threat of sharpshooters caused severe distress for the men, who could never feel truly safe from the foe’s pickets. “Men were killed in their camps, at meals, and several cases happened of men struck by musket-balls in their sleep,” said Union general David S. Stanley, while a Confederate artilleryman testified that under the continuous menace of Yankee sharpshooters “one of our detachments broke down utterly from nervous tension . . . some of these poor lads sob in their broken sleep, like a crying child just before it sinks to rest”.

The condition of the Southerners was even worse because of their lack of adequate rations and medicine. “The Lincolnite host still surrounds us”, wrote the Atlanta merchant Sam Richards. “Our general is trying to out-general and

Cheat-ham them out of a victory, but it appears doubtful which will gain the point . . . there is nothing much to be had to eat in Atlanta though if we keep the RR we shall not starve, I trust.” As it to drive home their vulnerability, Thomas unleashed an artillery bombardment upon Atlanta, forcing thousands of civilians to flee and other thousands to hide under cellars or in dugouts. “It is like living in the midst of a pestilence,” wrote Richards of the bombing. “No one can tell but he may be the next victim.” With the Army taking most provisions that arrived at the city, many civilians were reduced to looting or, as in Port Hudson before, to eat skinned rats and dogs. Fires broke out, and a surgeon testified that he had had to amputate the limbs of children wounded by the artillery barrage. But this was not enough to force Cheatham out. A Northern newspaper that had once declared that the capture of Atlanta was “a question of a few days”, now confessed to be “somewhat puzzled at the stubborn front presented by the enemy.”

Still, Cheatham realized that he could not withstand an extended siege. He again placed his hopes in cutting off Thomas’ lifeline. The impetuous Hood, who had continued to send messages to Richmond complaining of Cheatham’s passivity, proposed to dash around Thomas to his rear. The Union general would have no other option but to turn back, which would grant Cheatham an opportunity to attack, trapping Thomas between the two rebel forces. This plan was “dashing in the extreme”, for Thomas retained numerical superiority. The rebel hopes all laid on being able to defeat the scattered Federals before they could concentrate, which required a great deal of strategic coordination and even luck in an age before radio. Yet even Thomas had to concede, years later, that it probably was “the best plan that could have been adopted by the enemy” under the circumstances. Cheatham’s initial reluctance was overcome when Cleburne arrived at Atlanta, having given up in his attempt to stop Sherman in his march. “I can do no more than annoy Sherman”, Cleburne had declared morosely, after the Federal had conducted a brilliant campaign in Alabama that forced Richmond to decide whether to sacrifice Mobile or Atlanta.

The events that led Cleburne to make such a decision are as follows. After the failed Confederate attempt to turn Sherman back at Tupelo, there were acerbic discussions in the Southern headquarters. Forrest, though nominally under Cleburne’s command, blamed the Irishman for the failure. “If I knew as much about West Point tactics as you”, he complained in anger, “the Yankees would whip the hell out of me every day.” It is said that Forrest even threatened to shoot Cleburne if he dared to order him around. The fight was so pointed that the cooperation between the two Confederates effectively ended there and then, and both decided to execute their own, separate plans for stopping Sherman. In the meantime, Sherman retreated to Florence, where he could receive supplies through the Tennessee River. However, this increased the gap that separated him from C.F. Smith’s corps, which had continued its march to Montgomery and was now 160 miles away from Sherman’s main force. The only information Sherman had been able to obtain as to Smith’s whereabouts and situation came from Southern newspapers that jeered that “Smith and his Yankee force march to their certain destruction”. A cavalry incursion under the rather incompetent William Sooy Smith was turned away by Forrest, returning without news – and without their commander. This alarmed Sherman enough and made him rush to Montgomery on July 13th.

Forrest attempted to harass Sherman during his march, as he had vowed after directly facing him at Tupelo had failed. With usual bloodthirstiness, Forrest ordered his men to execute any captured Yankees, even issuing an order to do so with knifes or by hanging to preserve bullets. In response, Sherman ordered his men to “take life for life” and “devastate the land over which” Forrest “had passed or may pass”. They should “bring ruin and misery” to any population that supported Forrest or any guerrillas. The soldiers executed Sherman’s orders with ruthless efficiency, and continued to take everything they could and burn everything they could not. Many women and children were forced to beg for food, and some ladies apparently had to exchange sexual favors for anything to not starve. A Union soldier believed them a “pitiful sight . . . their poor, pale, emaciated faces too plainly speaking what they have suffered.” But neither pity nor Forrest’s harassment stopped Sherman in his march. “We will take all provisions and God help the starving families”, Sherman exclaimed when a plantation owner complained of how the Federals had stripped it bare. “I warned them last year against this visitation, and now it is at hand.”

Sherman marching through Alabama

Sherman, in order to confuse and elude Forrest, had at first marched to Columbus, Mississippi, before he veered to Tuscaloosa. That city was sacked and burnt, and by the time Forrest arrived he found little more than ashes. Sherman then continued towards Montgomery. More accurate intelligence had shown that Smith had, like his commander, lived off the land, devastating the towns of Talladega, Opelika, and Auburn, before he tried to take Montgomery itself. Cleburne, however, had managed to turn Smith back at the Battle of Tuskegee on July 20th. Smith knew nothing of Sherman’s whereabouts, less of all that he was now close to his position east of the Alabama River. Anxious of preventing the two Union forces from linking up, Cleburne had sent fake news that declared that Sherman had been grievously defeated, and when that failed to convince Smith, Cleburne prepared for battle. Sherman, for his part, advanced to Selma, believing that this would force Cleburne to come and face him. That city, an important industrial center, was defenseless except for a small fraction of Forrest’s troopers and hastily assembled militia. The panicking mayor even pleaded with Forrest to surrender the town less it be burned, but Forrest refused.

When Sherman arrived, he was informed by escaped slaves that the seemingly formidable fortifications were thinly manned because Forrest had failed to concentrate his force. The outnumbered rebels, many of them civilians who had been given a rifle just a few hours prior, had little chance of resisting the Yankee charge. Some of the people manning the trenches were in fact mere boys, pressed into service in desperation. “It was a terrible sight”, a bluecoat remembered in horror, “just a boy 14 years old; and beside him, cold in death, lay his Father and two brothers.” Drafting civilians in such a way was nothing but a “harvest of death . . . they knew nothing at all about fighting.” Bowing to the inevitable, Forrest fled from Selma, having burned 35,000 bales of cotton and other supplies beforehand. “Of all the nights of my experience, this is most like the horrors of war”, testified a soldier. ”A captured city burning at night, a victorious army advancing, and a demoralized one retreating.” Like in Shreveport and Meridian in previous campaigns, the Federals then proceeded to complete the destruction of the city by torching or blowing up what little industry or war resources remained.

A full-blown panic started in Montgomery in response to Selma’s fall. Amidst wild rumors of massacre and pillaging, including one that said that all males had been slaughtered and all females raped, the city fell into chaotic disarray. Civilians tried to escape by begging or stealing carts or horses, stores were looted, and even fires were started. An ominous warning then came from Sherman, telling the governor that “a people who will persevere in war beyond a certain limit, ought to know the consequences.” Panic immediately increased tenfold. As expected, Cleburne was left with no option but to rush to Montgomery’s defense, even if he believed he had little chance to beat back Sherman’s invaders. As Sherman moved to Montgomery, he ordered McPherson and his corps to attack Forrest, to prevent him from coming to Cleburne’s aid, and then started to bombard the city. As in Atlanta, the Yankee shelling drove the people into a “wild state of excitement.” People ran about the streets “in every direction . . . striving in every conceivable way to get out of town with their effects.” When Smith rejoined Sherman, the Yankee force then went forward and attacked Cleburne’s trenches with a “perfect rain of Minie balls”. But the next morning, the attack ceased and when the scared citizens dared to peer out of their walls, they discovered that Sherman had disappeared. Scouts informed Cleburne that Sherman was now advancing to Mobile, a more strategically important target. His objective, Cleburne realized, had merely been to reunite with Smith and clear the path to the sea.

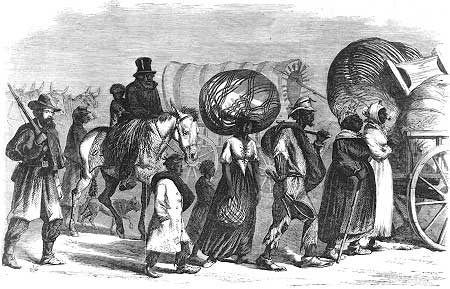

Forrest came to the same conclusion regarding Sherman’s plans belatedly. McPherson had been sent as a mere diversion, and by pursuing him Forrest had fallen right into his trap and now could do nothing about Sherman himself. His weakened force was unable to do much against McPherson either, although the cautious McPherson was unwilling to risk an all-out battle either. McPherson’s march was more significative because as his force advanced through the Black Prairie, a fertile breadbasket with counties where over 75% of the population was enslaved, the Yankees uprooted slavery and treason “like a decrepit weed”. The mostly Black corps carved a path of destruction with scarce opposition in their path. A planter would forever remember the day when McPherson arrived at his property, “like a one-armed Gabriel, blowing the trumped that announces our irrevocable perdition”. But the perdition of White planters could mean the liberation of other groups. As McPherson advanced, the enslaved stepped forth to receive him with cheers and joy. With an "abiding faith that they would be led to a land of liberty and a land filled with plenty for them," they joined McPherson's troops with an “assortment of animals and vehicles, limping horses, gaunt mules, oxen and cows, hitched to old wobbly buggies, coaches, carriages and carts.”

Freedmen following the Union Army

Soon enough anywhere from ten to twenty thousand freedmen were following McPherson, while thousands more had been liberated, armed, and settled in the properties of their former owners. McPherson, an early supporter of the home farm project, had basically instituted the same system in the lands he passed. The comparison with Moses seemed to many freedmen particularly fitting, for in following McPherson they believed he was leading them to a new promised land, and that this initial march was akin to the Israelites wandering through the desert. A Union chaplain even said, with a mix of befuddlement and amusement, that some of the freedmen thought that McPherson

was Moses. A similar reception awaited Sherman in his march from Montgomery to Mobile, with thousands of slaves leaving their plantations to join his Army and cheer him on. “The negroes”, he reported, “flock to me old and young, they pray and shout and mix up my name with that of Moses and Simon and other Scriptural ones as well as Abum Linkum, the great Messiah of 'Du Jubilee!'” Unfortunately, they received a much less friendly reception compared with McPherson. “William Tecumseh Sherman despised black people and felt no distaste for slavery”, Bruce Levine states unequivocally. “He was happy to make use of black labor”, but “refused to enlist such men as soldiers”, because he, in his own words, could not “bring myself to trust negroes with arms in positions of danger and trust.”

Sherman never conciliated himself to the fact that the Union Army was bringing a complete social and economic revolution to the South, only accepting emancipation reluctantly and resisting anything that might result in giving Black people “an equality with whites” he believed they didn’t deserve. Sherman, both consciously and unconsciously, encouraged callousness against the freedmen within his men, allowing them to destroy their meager belongings and refusing to help the old or the infirm. On one occasion, Sherman did nothing as a group of freedmen was massacred by vengeful Confederate cavalry. Even a slaveowner had to wonder how the enslaved could “regard the Yankees as their best friends” when they had “suffered every form of injury from them in their persons and property”. An enslaved man replied then that they “preferred death by Yanks than longer to live with their cruel masters, in slavery.” Despite this willingness to endure Sherman’s contempt for a chance to live in freedom, Sherman’s actions still dismayed the Union authorities when they learned of them. Sherman “manifested an almost

criminal dislike to the negro”, worried Secretary Stanton, and Henry Halleck, who “sympathized with Sherman’s opinions”, nonetheless suggested he at least give “escaped slaves . . . a partial supply of food in the rice-fields and cotton plantations”.

These were the criticisms that awaited Sherman when he reached Mobile on August 20th and finally managed to report back to Philadelphia. Grant himself had, alongside a congratulatory message, advocated for the settlement of the freedmen. It is deeply ironic that, in spite of his racism and conservatism, Sherman ended up producing one of the war’s most radical field orders in response to this pressure and the need to get rid of the freedmen who burdened his Army. Special Field Orders No. 15 reserved all the confiscated lands between Montgomery and Mobile for the “exclusive settlement” of the freed slaves and assigned the radical General Rufus Saxton to manage the project with instructions to provide the freedmen with provisions and farming supplies. A subsequent order then formalized McPherson’s actions, by recognizing the land redistribution the general had carried out in northern Alabama and Mississippi, by then a fait accompli. This is the origin of “forty acres and a mule”, for even if the home farm system had been implemented beforehand in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia, this was the first time it had been executed in such a scale. “Once again, the logic of events had induced an unlikely individual to advance the interests of the former slaves”, concludes Levine.

Sherman’s march to Mobile had left in its wake a devastated Alabama and dealt slavery a fatal blow. Hundreds of thousands of acres had been confiscated and then redistributed, and the destruction wrought in the Black Prairie had destroyed vital supplies the Confederacy badly needed. But Sherman had been unable to catch Cleburne, who once again slipped to Atlanta to help Cheatham. McPherson had also failed in his effort to corner Forrest, although the raider was weakened enough that he had had to retreat to Tennessee. More importantly, when Sherman finally reached Mobile he found the city still standing. Banks’ siege of Spanish Fort had gone nowhere for two weeks, some 2,000 rebels managing to hold off over 20,000 bluecoats. When the breaking point was almost reached, the Confederates simply evacuated to the more formidable Fort Blakeley. An attack by a frustrated Banks on July 20th only resulted in terrible casualties, and a new siege that was still going on a month later. Needless to say, the whole campaign failed to assuage Northern anxiety, and although many praised Sherman for making Alabama howl, just as many criticized him for not destroying Cleburne, for not taking Mobile or Montgomery, or, in the case of Republicans, for failing to protect the freedmen. Sherman’s entire march had been nothing but a “horrifying fiasco”, said the Copperhead

Old Guard. “Every species of marauding . . . seems to have been not only tolerated but encouraged,” the paper fumed. “All just people,” looked on “with amazement and horror at our atrocities and barbarism.”

August was coming to an end and the Union seemed to be at the exact same position that at the start of the month: stalemate in Virginia, and fruitless sieges in Atlanta and Mobile. It seemed like the Confederates’ objective of making the war too costly for the Northern people to continue was at hand. “If nothing else would impress upon the people the absolute necessity of stopping this war”, shouted Copperhead editorials, “its utter failure to accomplish any results . . . would be sufficient.” Even once unflinchingly loyal men now expressed doubts, like Thurlow Weed who declared Lincoln’s reelection “an impossibility” because “the people are wild for peace”. Peace was just around the corner, Southern newspapers assured their readers. Northerners “are sick at heart of the senseless waste of life” and would soon elect a Chesnut that would stop the war. Northern Copperheads echoed this idea, like a Boston conservative that hoped that Northerners would realize that “the Confederacy perhaps can never really be beaten, that the attempts to win might after all be too heavy a load to carry, and that perhaps it is time to agree to a peace without victory.” The lack of progress and victories, a strong racist backlash on account of all the Radical measures adopted, and the renewed vigor of the National Union all combined to bring the Lincoln administration to its worst crisis since the aftermath of the Peninsula. As Sherman wrote his wife grimly, “the worst of the war is not yet begun, the civil strife at the North has yet to come.”