There were a lot of veterans associations and soldier's homes established after the war. I've done a bit of civil war reenacting at the one in Milwaukee (near Miller Park Stadium, its part of the VA's grounds).

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"In order to have a better post war America, it will take more than a few good presidents; it will also need a pro civil rights Supreme Court to ensure that no roll backs happen. Maybe Lincoln pulls a William Howard Taft and is nominated to be an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court, or perhaps even Chief Justice after Salmon Chase dies during the 1870s (if he still gets the post that is).

I actually have Lincoln become Chief Justice in 1861 in my Triumphant timeline.

I actually have Lincoln become Chief Justice in 1861 in my Triumphant timeline.

Lincoln as a Justice is a great idea, I've seen a few TLs where he ends up there and not President, so it would definitely be a good thought.

Washington wasn't perfect either, and people revere him; I think LIncoln will still go down in history well here, but perhaps like FDR - - FDR is a solid 3rd at worst in most historians' eyes, and some put him 1 or 2, because of the Depression and WW 2. Lincoln's mistakes will likely look better by comparison than, say, FDR's treatment of Japanese-Americans, too. Or, if not, his mistakes will be seen the same way, just sort of glossed over.

That was a great narrative. As for desertion, I remember not only reading about Hooker, but also that the whole notion of leaving and then returning was shown in "The Red Badge of Courage." Speaking of which, it may be a little darker this time. Instead of OTL's Chancellorsville, it might take place during the coming invasion of the NOrth. I mean, Hooker didn't even get as far as he did OTL in TTL.

Then again, maybe the battle TTL is so bad, the author has the main character coming back to fight in Lee's invasion.

Washington wasn't perfect either, and people revere him; I think LIncoln will still go down in history well here, but perhaps like FDR - - FDR is a solid 3rd at worst in most historians' eyes, and some put him 1 or 2, because of the Depression and WW 2. Lincoln's mistakes will likely look better by comparison than, say, FDR's treatment of Japanese-Americans, too. Or, if not, his mistakes will be seen the same way, just sort of glossed over.

That was a great narrative. As for desertion, I remember not only reading about Hooker, but also that the whole notion of leaving and then returning was shown in "The Red Badge of Courage." Speaking of which, it may be a little darker this time. Instead of OTL's Chancellorsville, it might take place during the coming invasion of the NOrth. I mean, Hooker didn't even get as far as he did OTL in TTL.

Then again, maybe the battle TTL is so bad, the author has the main character coming back to fight in Lee's invasion.

Thomas1195

Banned

If we look at the English Civil War and especially the colonial theatre, that war was literally the prequel of the American Civil War.

ITTL, this is even more of the case given the radicalization that is happening on both sides.

ITTL, this is even more of the case given the radicalization that is happening on both sides.

Last edited:

That story was quite got. Gives a reminder of how hellish the war actually is on the ground, and shows how an 'I just want to go home' greenhorn gets radicalized into utter hatred for the CSA.

Deserves a threadmark.

Deserves a threadmark.

Chapter 36: Fire in the Rear

The weeks after the defeat at the Battle of Bull Run were the darkest months for the Union cause. As Lee and his victorious rebels prepared to cross the Potomac and invade the North, the morale of the people sank to its lowest levels since the start of the rebellion, and Confederate independence seemed practically assured. The Lincoln administration was forced not only to face the insurgent armies, but the bitter opposition of the increasingly powerful Copperheads and a serious challenge to his leadership from his own party. Partisan violence and political polarization covered the nation in blood, creating a step human cost that broke the will of many Union men. It was not clear whether Lincoln would be able to weather such a disastrous situation. It was truly the darkness before the dawn, and although things would get better eventually, just how close the Union came to defeat cannot be understated.

Perhaps more threatening than even Lee’s rebels were the Copperheads. So Lincoln confessed to Charles Sumner, saying that he feared more “the fire in the rear” than battlefield reverses. After the War Unionists were discredited and wiped off in the 1862 midterms, Peace Chesnuts known as Copperheads took over the Party and transformed it into an organ of anti-war unrest. Cut off from political power due to “this most disastrous epoch” that started with the 1858 midterms and made the Republicans the dominant political force in the North, Copperheads were forced to express their opposition to the war and to the Lincoln administration’s policies through violence, fraud and agitation. Emboldened by the latest military setbacks and by a strong racist backlash, Copperheads started a campaign of resistance that almost sunk the Union during the months following the Peninsula disaster.

The Copperheads’ most frequent charge was, of course, that Lincoln had set aside “the war for the Union” and in its place “the war for the Negro was begun.” The Copperheads argued openly that the war was a result of Republican fanatism, and that secession was a justified response to abolitionist attacks. The continuation of the war was just a result of Lincoln’s stubborn intransigence, and dropping emancipation as a war goal would be enough for hostilities to cease and constitutional reunion to take place. As Clement Vallandigham proclaimed, “In considering terms of settlement we [should] look only to the welfare, peace, and safety of the white race, without reference to the effect that settlement may have on the African."

Vallandigham was one of the most conspicuous Copperheads. The Ohioan had been the protagonist of a political drama in 1856, when he alleged that voting fraud had cost him a House seat. A House committee filled with Douglas Democrats took his side eventually, but the question was rendered moot when he lost the seat anyway in the 1858 Republican wave. Again, Vallandigham cried fraud, and evidence of scheming by the Buchanan Democrats lend credence to these claims. The result was that Vallandigham became something of a martyr of the Douglas-Buchanan feud, and he knew to exploit this by becoming one of Douglas’ staunchest supporters in his feeble 1860 campaign. The start of the war and Douglas’ triumphant comeback had served Vallandigham well, though even at that point he expressed a worrying sympathy with the South. After the Copperhead takeover, Vallandigham became the leader of the pro-peace faction.

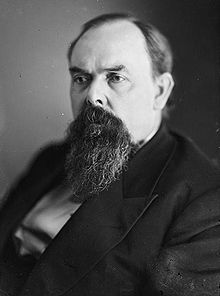

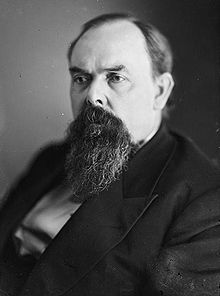

Clement Vallandigham

The war, Vallandigham asserted in a speech before a large Ohio crowd just a few days after the Battle of Bull Run, had resulted in nothing but "defeat, debt, taxation, sepulchres . . . the suspension of habeas corpus, the violation . . . of freedom of the press and of speech . . . which have made this country one of the worst despotisms on earth for the past twenty months." “The dead of Manassas and Vicksburg” showed that attempts at forcible reunion had only resulted in “utter, disastrous, and most bloody failure.” The South could not be conquered, and Lincoln’s only option was to “Withdraw your army from the seceded States” and start negotiations for an armistice. Emancipation could not and should not be demanded as a precondition of peace, because there was “more of barbarism and sin, a thousand times, in the continuance of this war . . . and the enslavement of the white race by debt and taxes and arbitrary power”.

It's evident that aside from the old issues of Emancipation and what the objective of the war ought to be, the opposition adopted the new issues of martial law, military arrests, and conscription as rallying cries. Just like in the South, conscription had caused widespread discontent with the government and outright defiance in many occasions, as men reluctant to take place in a seeming failure of a war sought to escape the draft by any means, including violence. The Enrollment Act of 1863, passed shortly after the New Year, was similar to its Confederate counterpart in that its primary objective was to stimulate volunteering, but the law worked with “such inefficiency, corruption, and perceived injustice that it became one of the most divisive issues of the war” and a focal point of resistance to the Lincoln government.

The Enrollment Act, like other pieces of war-time legislation, was revolutionary in its nationalizing spirit, for the draft would not be conducted by the individual states but directly by the War Department. Stanton and his corps of Provost Marshals enforced it with the ruthless efficiency that characterized the Secretary, but unfortunately not even the incorruptible Stanton could assure complete honesty in the entire process. Individuals failed to report when their names were drawn from the lottery, skedaddling to swamps or other countries. Or they bribed officials to report a false dependency by an orphan child. Prostitutes were hired to pretend to be an indigent mother who pleaded for “her” son to remain home. Some feigned illness or injury, or bribed medics to declare them unfit for duty. One Doctor Beckwith even unabashedly sold certificated of unfitness for $35 dollars. If that failed, some men went as far as mutilating themselves, by cutting off fingers or pulling teeth.

Conscription was such an explosive issue because for many Northern communities it was the first time they had truly felt the hard hand of war. The parades of 1861 had of course left an indelible mark in the memory of thousands, but those were young idealists who volunteered for a war they thought would be short and glorious. It was completely different for “a young man to be torn from his farm and family” to fight in a conflict that seemed hopeless at the moment. “Few issues affected the home front so directly”, comments Donald Dean Jackson, “and few so severely tested the North's resolve to act as a nation”. Alexis de Tocqueville had once declared that "the notions and habits of the people of the United States are so opposed to compulsory recruitment that I do not think it can ever be sanctioned by their laws." This was now to be tested.

An aspect of the law that increased resistance to it was the fact that both volunteers and draftees would be assigned to existing regiments. During the original call for volunteers, the desire to serve with neighbors and friends and the pride of fighting in a unit named after one’s hometown had served as effective means of stimulating volunteers. Now, it was clear that green troops would perform better if aided by veterans. The need was further underscored by the simple if grim fact that many units only existed in paper, two years of war having resulted in their almost complete extermination, leaving on their wake entire towns “where only women, children and the elderly” remained. This was not without its consequences, for many veterans regarded the new conscripts with contempt, saying that "Such another depraved, vice-hardened and desperate set of human beings never before disgraced an army," and characterizing them as "bounty jumpers, thieves, roughs and cutthroats".

Civil War Conscription

It can be discerned from these statements that special contempt was reserved for the so-called “bounty-jumpers”. The term referred to men who claimed bounties offered by the Federal government or local jurisdictions, only to then desert and claim another bounty. The practice of offering such bounties started with the war, as a way of offering subsistence to homes that lost their breadwinners. But as war fever ebbed and the need for fresh recruits increased, the sums offered started to climb as well – and with them the potential for fraud. After the Enrollment Act was passed, bounty jumpers were able to make easy fortunes by claiming several bounties or offering themselves as substitutes several times. One Connecticut youth, for example, sold himself for $300 and then bought a substitute for $150. “Substitute brokers” went into business as a way of obtaining the highest possible bounties for their clients, and insurance firms started to offer “draft polices” that gave from $300 to $500 so that clients could hire a substitute if drafted.

Substitution, as said in earlier chapters when Confederate conscription was discussed, had such deep roots in European and American military history that its inclusion was not questioned. This did not stop charges of “a rich man’s war, a poor man’s fight”, as the soaring price of substitutes meant that only the well-off could contract them, while the poor man would inevitably end up in the army. Around a little Vermont town, the price of substitutes rose to over 900 dollars, while Cortland practically bankrupted itself by paying for substitutes to “preserve the unity of families intact and snatch unwilling victims from the moloch of war”. “The Rich are exempt!”, cried an outraged Iowa newspaper.

Originally, Republican lawmakers intended to include a 300 dollars commutation fee as a way to cap the price of substitutes and put it within the reach of the poor. So said Senator Wilson, who believed that the law ought to “throw a dragnet over the country and take up the rich and the poor and put the burden upon all." The commutation fee would also work similarly to Southern occupation exceptions, by keeping those valuable to the war effort on the home-front. But the outcry against “blood money” was so severe that Republicans decided to not include the $300 dollar fee, instead creating a series of exceptions that included not just respectable white-collar occupations like telegraph operators, teachers, clergymen and clerks, but also some common occupations like firemen, miners or industrial laborers. Racial resentments were also soothed by the fact that Black men were also liable for conscription, though it was limited to free people for the moment.

The draft produced extremely bitter and partisan denunciations by Copperheads who saw conscription as “an unconstitutional means to achieve the unconstitutional end of freeing the slaves”. A Pennsylvania lawmaker denounced the law as “unconstitutional, unjust, unjustified,” and a Chesnut convention pledged to “resist to the death all attempts to draft any of our citizens into the army”. These pledges were not merely words, for communities were ready to resort to violence to preventing conscription from taking place. In Wisconsin, eight companies of troops had to be summoned after a mob carrying a banner that said “No Draft!” murdered an enrollment officer, and two others shared this unhappy fate in Indiana. A Pennsylvania officer received a threatening letter: "If you don't lay aside the enrolling, your life will be taken tomorrow night”. More officials forms of resistance abounded too. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court produced a ruling that declared the draft unconstitutional (the government ignored it), and even the Republican Governor of New Hampshire warned that the draft could only be enforced in his state with the presence of an infantry regiment.

The greatest basis of opposition, of course, came from the Chesnuts, who used their favorite weapon to great effectiveness. Emphasizing the point that the draft would force White men to fight for Negro emancipation, Chesnut politicians and newspapers denounced conscription in racist terms. An editor told a Catholic meeting that the President “would be dammed if he believed they would go and fight for the nigger,” while a Chesnut speaker said that slave emancipation would bring thousands of freed Blacks to "fill the shops, yards and other places of labor" soldiers had left behind, thus forcing “the poor, limping veteran” to “compete with them for the support of our families." Samuel S. Cox said that the real cause of the war was the "Constitution-breaking, law-defying, negroloving Phariseeism of New England" A National Unionist meeting resolved they would fight for Uncle Sam, “but never for Uncle Sambo”. Class tensions and racism were reinforced by diverse incidents, like in New York, where striking Irishmen were replaced by Black laborers.

Throughout the North there were many outbreaks of anti-draft resistance

In the face of such resistance, the Lincoln administration once again took extreme measures to enforce the draft. To prevent judges from issuing writs of habeas corpus to free conscripts, he suspended the writ nationwide once again, and authorized the arrest of anyone who discouraged enlistment or engaged in other kinds of “disloyal practices”. This included the arrest of disloyal newspapers, and some people apparently even began to carefully consider what they said in personal letters. A Chesnut Senator charged that through these actions Lincoln was “declaring himself a Dictator, (for that and nothing less it does)”, and reports of men jailed merely for “hurrahing Johnny Breckenridge” abounded. War Unionists had been willing to accept such arrest during the first months of the war as a way to stamp out treason in the Border South. “I grant, sir, that there was a time when anarchy and confusion reigned in the Border Slave States” and such arrest were necessary, declared one of them. But “that there can be no such justification, no palliation, no excuse”, for arrests in “the loyal states of the North” far from the frontlines.

On February 15th, the War Department issued a series of infamous regulations that allowed military commanders “to arrest and imprison any person or persons who may be engaged, by act, speech, or writing, in discouraging volunteer enlistments, or in any way giving aid and comfort to the enemy, or in any other disloyal practice against the United States”. A series of sweeping arrests followed. In those feverish months were the very fate of the Union seemed at stake and scared Unionists saw treason and butchery in any corner, the scenes in several Northern communities approached those of the French Revolution, with mere accusations being enough to have someone arrested. Mark E. Neely condemns these events, arguing that the February orders, called mockingly “Lincoln’s 14 Frimaire” by opposing Chesnuts, “showed the Lincoln administration at its worst—amateurish, disorganized, and rather unfeeling.” Altogether, almost a thousand men were arrested during the period of February to May 1863.

In reaction to these events, Chesnuts from all over the country denounced Lincoln as a “despot . . . who disregards the Constitution in the name of fanatism” and prosecuted a war “for the benefit of Negroes and the enslavement of Whites”. Horatio Seymour, the defeated 1862 candidate for the New York Governorship, said that emancipation was “bloody, barbarous, revolutionary" and that he would never accept the doctrine that that the loyal North lost their constitutional rights when the South rebelled.” Representative Cox, an Ohioan like Vallandigham, charged Lincoln with taking actions “unwarranted by the Constitution and laws of the United States”, which constituted “a usurpation of power never given up by the people to their rulers.” The New York Atlas attacked “the tyranny of military despotism” and “the weakness, folly, oppression, mismanagement and general wickedness of the administration at Philadelphia.” A common denunciation was that the law was most commonly employed against Chesnuts as a way of getting rid of political opponents. One woman, for example, denounced that Union soldiers broke into her home in the middle of the night and took away her husband. His crime was simply attending a National Union convention.

Lincoln justified these actions by declaring that in a civil war such as the nation faced, the entire country constituted a battlefield. He insisted that it was necessary to arrest those “laboring, with some effect, to prevent the raising of troops [and] to encourage desertions”, for they were “damaging the army, upon the existence and vigor of which the life of the nation depends”. Conducting such actions in the North was justified, for "under cover of 'liberty of speech,' 'liberty of the press,' and Habeas corpus,' [the rebels] hoped to keep on foot amongst us a most efficient corps of spies, informers, suppliers, and aiders and abbettors of their cause." The suspension of civil liberties, Lincoln concluded, was “constitutional wherever the public safety does require them.” Using a “homely metaphor”, the President promised that such excesses would not continue in peace-time, and arguing that they would was like saying “that a man could contract so strong an appetite for emetics during temporary illness, as to persist in feeding upon them through the remainder of his healthful life.”

These arguments, published on the New York Tribune, were accepted by Republicans who had entered into a crisis mode. As in other revolutions and wars, the people craved strong government and decisive action in order to protect their safety and assure ultimate victory, and this helps explain why the North was willing to accept such flagrant violations of civil rights. The overarching reason was, naturally, news of rebel atrocities in the South, which caused such a political polarization in the North that soon enough everyone who did not support the Union was accused of treason and of being in favor “of the butchery of women and children and the total extermination of the Union men of the nation.” The people did not merely welcome Lincoln’s actions, but took justice in their own hands in order to suppress any perceived treason, freely using intimidation and violence.

Political opponents were charged with being supporters of the rebellion and their atrocities

In Ohio, an editor was stopped from publishing an anti-war article after a mob appeared before his house with a guillotine, emblazoned with the message “the remedy for treason.” A Massachusetts editor was less lucky, for after he criticized the government a mob formed outside of his house. Accusing him of being in favor of “rebel marauders”, the mob seized him and gave him a coat of tar and feathers before exiling him from the town. An anti-war orator was shot when he dared venture into an Indiana town that had suffered a rebel raid, the townsfolk crying that it was the fault of traitors like him that the war continued. Deserters and draft dodgers were shamed and shunned by their peers. The story of a young man who was given a dress by his sweetheart after he refused to enlist seems quaint when compared with the stories of a Pennsylvania town were fears of rebel invasion had whipped the people into a frenzy. There, draft dodgers were marked with the letter “T” by people who said they wanted to aid the rebels in their rapine and massacre, and one deserter was tied to a tree and set in fire.

Just like how Chesnuts accused African Americans of being the cause of the war, Republicans started to accuse Copperheads of being the cause of the latest failures. A year ago, one editor had asked why the 20 million loyal people of the North hadn’t been able to overcome 5 million rebels; now, a Radical editorial offered an answer: “The fault lies in every wiley agitator, who encourages desertion and cowardice, and . . . enter into intrigues with rebels to assure our defeats.” Indeed, McClellan had been a National Unionists, hadn’t he? And Vallandigham was encouraging desertion even as Lee advanced into Pennsylvania, whose people were afraid of suffering like the Kansans and East Tennesseans had. If the National cause was to be victorious, any such show of disloyalty had to be trampled and exterminated, until only “true Union men” were in charge. A horrified man interrupted a speech given to this effect by predicting rivers of blood and terror far beyond the worse Jacobin excesses. The speaker, to enormous cheers, replied that “if scaffolds and guillotines from the Susquehanna to the Rio Grande be needed to preserve this temple of freedom, I say, let it be done.”

Accordingly, Copperheads suffered abuse and violence at the hands of Radicals who blamed them for military reserves and war atrocities. When a Copperhead advocated for resistance to the draft, a mob of women formed to confront him. They said that many of their husbands had fallen in battle for lack of support in the Homefront, and that “traitors such as you, sir, are the direct cause of such want of morale and men” in the battlefield. The women proceeded to tar and feather the man, and when another man tried to intervene, they hit him with bricks and sticks, giving him a severe concussion. A similar but even worse fate befell a peace speaker who was confronted by Union soldiers in furlough. They all had lost comrades in rebel raids, and, enraged by “this open advocacy of treason at our very homes”, they attacked him, breaking his arm and leaving him bleeding from a head wound. Copperhead newspapers were attacked and burned to the ground, and “Union League” militias broke National Union conventions.

These lamentable events reflect the developing of an “us vs them” mentality that meant that anyone that did not support the war and the government was a traitor who cheered for rebel murderers. One Republican congressman so complained, saying that he did not endorse “Lincoln’s Robespierrean campaign”, but that if he voiced such opposition he would be heckled as being a traitor and treated as if he were “personally responsible for the latest rebel outrages.” Some political “purges” took place as people who did not support the war’s prosecution were charged with being for disunion. One Republican was forced to vote for a bill empowering Lincoln to suspend Habeas Corpus. He at first fretted that he would not win reelection, but a colleague dispelled these fears: “Reelection? You’d better get your nomination first. Haven’t you learnt that it is the Radicals who do that job nowadays?” A moderate Republican was accused of being a Copperhead by a mob that fierily declared they could forgive rebels, but never a Copperhead. Intimidated by their presence, the politician was forced to call for Breckenridge to be hung from a sour apple tree before the mod dispersed.

Union Leagues and Loyal Publication Societies began to spring throughout the North, carrying stories of rebel atrocities and interviews with people who suffered under their rule or their raids. The Republicans were not above extralegal or even outright illegal actions in order to assure victory. Indiana’s Governor, Oliver P. Morton, convinced the Republicans in the National Union legislature to withdraw, preventing a quorum. Forced to run the state without the usual appropriations, Morton borrowed from banks and received $250,000 dollars from the War Department. An attempt to do likewise in Illinois, where very slim Republican majority in the Legislature ruled alongside the radical Governor Yates, failed because Federal troops arrested National Unionists and held them forcibly in the Legislative chambers for some important votes. Accused then of dereliction of duty, they were forced to resign their seats and were promptly replaced by Republicans in elections where fraud was alleged.

Oliver P. Morton

Extralegal actions were also taken to prevent the Governorships of Connecticut and New Hampshire from falling into Copperhead hands. The War Department furloughed Connecticut soldiers (and some, it’s said, from other states as well) to allow them to go home and vote the Republican ticket. Widespread violence and fraud were reported, as Union League paramilitaries guarded the ballot boxes. Anyone seen as sympathetic to the Copperheads was prevented from voting, and a woman who leaned towards the Radicals talked of “a glorious campfire made with the votes of traitors.” In New Hampshire such methods were not required due to a third candidacy by a War Unionist, who split the anti-Republican vote. The election was thrown to the Republican legislature which, obviously, elected their man.

This split is emblematic of a deeper division within the National Union. The main division was, of course, between War Chesnuts and Copperheads. Since both camps were committed to reunion and opposed to the Lincoln administration, an alliance was easy to maintain as long as those twin goals were maintained. But as the war degenerated into a desperate struggle that would see one side victorious and the other completely defeated, it became obvious that reunion could only be effectuated by a complete triumph over the enemy. Thus, a new division between the Peace Chesnuts who only accepted peace if it came with reunion, and the Copperheads, who considered war and abolition such great evils that they were willing to accept disunion. It’s dubious that all Chesnut were willing to accept this, but in the face of such political polarization and with Northerners worried about their very survival, any pro-peace sentiment was denounced as disunionist and treasonous, and advocacy for massacre and rapine.

This was a conundrum for Douglas Chesnuts who followed his maxim of country over Party and rejected partisan attacks in favor of a crusade for the Union. Some, of course, had been alienated by emancipation and the new radical measures. But as Copperheads came to accept disunion as the price for peace, the question for these War Chesnuts became whether they were willing to accept abolition as the price for Union. Some, such as Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, did so. More astoundingly, there were men like Benjamin Butler, who had supported Buchanan and Breckenridge and was now well on the road to become a Radical Republican. Complicating matters was the lack of coherence and unity of purpose of the National Union. Formed by Douglas as a popular sovereignty party, it had crashed disastrously in 1858 and 1860, and even in 1863 it was unable to find a coherent basis of opposition or command loyalty to the party itself.

The rebels themselves shot down Copperhead hopes of peaceful reunion by their demands for Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky and their terrible acts of terrorism against Unionists. Vallandigham, conferring illegally with Confederate agents in Canada, pushed forward for reconciliation, and asked them for support in a campaign for the Ohio governorship, promising that "the peace party of the North would sweep the Lincoln dynasty out of existence." The Confederate agents replied that he was “badly deluded”, and in response Vallandigham said that they would be open to recognizing Confederate independence if they refused to come back. A Union spy recorded these conversations and leaked them to the press, where the Union League took care that they were spread far and wide to both show that Copperheads were traitors and also that War Chesnuts had only two options: peace and disunion, or war and Union.

The portrait of the Copperheads as just another set of traitors took special importance when news of treasonous conspiracies in the Midwest and New York started to be reported. In New York, there were widespread rumors “of a purpose by the local Copperhead population to raise in insurrection” at the same time as Lee’s invasion, in order to assure a Confederate victory. Curiously enough, there apparently was not a great reaction to these reports, which leads one to suspect that they were created later with the benefit of hindsight. Rumors of plans for the formation of a Midwest Republic that would conclude a separate treaty of peace and perhaps even join the Confederacy abounded, and caused greater fears at the time.

Reports of dealings between Copperheads and rebels stiffened the resolve of the Republicans

Besides the racism that sadly characterized the region, Midwestern resentment was partly a result of economic grievances. The Mississippi was still closed, and the mighty river had been the main venue of commerce and transport of these states previous to the war. Now they had to rely in railroad commerce with the East, which they frankly saw as degrading. An Ohio editor went as far as saying that the region would "sink down as serfs to the heartless, speculative Yankees”, after being “swindled by his tariffs, robbed by his taxes, skinned by his railroad monopolies." “The rising storm in the Middle and Northwestern States,” a loyal Illinois man predicted, would cause “not only a separation from the New England States but reunion of the Middle and Northwestern States with the revolted States.” Already alarmed Republicans started to see “Treason... everywhere bold, defiant—and active, with impunity!”.

News of complots like this one and of prominent Copperheads conferring with rebel agents increased the perception of the National Union as just “another organ of the Breckenridge insurrection” and their speakers as people employed directly by Richmond. Republicans started to see in fevered nightmares a future where the Confederacy had taken not only the Border States but the Midwest and Pennsylvania and engaged in the extermination of all loyal men there. Copperhead support for unconditional peace and Republican pushes for unconditional victory put Conservative Republicans and War Chesnuts in a very uncomfortable condition. “What am I to do”, one of them lamented, “on one side there are the abolitionists and their radical objectives, on the other there are traitors, defeat and dishonor.” Some Republican conservatives would have surely deserted their party had the opposition been more moderate. Instead, they found themselves in the company of “traitors and Copperheads”. Unable to accept this, most remained in the Republican fold, even if reluctantly.

Some pinned their hopes in the creation of a grand conservative party that would limit itself to “the constitutional prosecution of the war” a scheme that men like Horatio Seymour, Thurlow Weed and even Lincoln himself at times seemed to favor. But if the National Union coalition was floundering due to divisions between pro-war and pro-peace faction, the differences between Republicans and Chesnuts were much more fundamental and much more severe, and they precluded any attempt to form such a coalition. The accusation that people who did not support the Administration were Copperheads and the violent actions taken to suppress them also forced many to choose. ‘There are few journals in this city in whose columns, during the present civil war, can not be found invocations to violence against dissentients from their opinion”, bemoaned Samuel J. Tilden. The result was that opposition to the Lincoln administration remained incoherent, divided and weak, unable to present a united front.

This was very fortunate for Lincoln, for a more competent opposition might have been able to force him out at that time of crisis. As things were, he was barely able to resist sagging civilian morale and challenges to his leadership from his own party. “Failure of the army, weight of taxes, depreciation of money, want of cotton . . . increasing national debt, deaths in the army, no prospect of success, the continued closure of the Mississippi [River] . . . all combine to produce the existing state of despondency and desperation”, said the Chicago Tribune, adding that “the war is drawing toward a disastrous and disgraceful termination.” Harpers Weekly declared that the people "have borne, silently and grimly, imbecility, treachery, failure, privation, loss of friends, but they cannot be expected to suffer that such massacres as this at Bull Run shall be repeated”. A Maine soldier wrote home that “the great cause of liberty has been managed by Knaves and fools. The whole show has been corruption, the result disaster, shame and disgrace.”

Even some Republicans were now willing to accept peace. A soldier confessed that "my loyalty is growing weak. . . . I am sick and tired of disaster and the fools that bring disaster upon us. . . . Why not confess we are worsted, and come to an agreement?" The erratic Horace Greeley, who swung from radical demands of emancipation to loud yelps for peace depending on battlefield fortunes, even proposed a hare-brained scheme for peace that involved an offer of mediation by Napoleon III. Greeley’s action so offended Seward that he threatened to have him indicted under the Logan Act, but they do reflect Northern despondency. "Our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country," he wrote, "longs for peace—shudders at the prospect of terrible conscription, of further wholesale devastations, and of new rivers of human blood."

Many Republicans blamed Lincoln for the course the war had taken. They accused him of being a “half-witted and incapable idiot”, even intimating that his “secesh wife, the Traitoress Mrs. Lincoln” had prevented a vigorous prosecution of the war. Minnesota’s Senator Wilkinson would declare that there was no hope “except in the death of the President and a new administration.” Former Justice Samuel Curtis found that most Republicans agreed on “the utter incompetence of the Pres[iden]t . . . He is shattered, dazed and utterly foolish.” A Michigan representative thought Lincoln “so vacillating, so week [sic] ... so fearful... and so ignorant... that I can now see scarcely a ray of hope left.” Richard Henry Dana Jr. found “the most striking thing is the absence of personal loyalty to the President. It does not exist.” Wild rumors circulated in Philadelphia, saying that the entire cabinet would resign and be replaced by War Chesnuts or even Copperheads, or that Frémont or Butler would be called to act as dictator, or that Radical Republicans planned to depose Lincoln and create a Revolutionary Directory to rule the country.

William Pitt Fessenden

Much talk was focusing on bitter recriminations against the Cabinet. Moderates charged Stanton and Chase were malign influences that were pushing Lincoln to radical measures, but moderates had also been pushed towards radicalism as a result of Southern atrocities. “Go and vote for burning Churches, raping women, and massacring Union men”, Senator Wade goaded, “or vote with the Chesnuts, which is the same thing.” They still felt uncomfortable with the prospect of a crusade for abolition and the complete destruction of the South, but were much more willing to accept hard war measures as a reaction to Southern terror. They recognized in Lincoln a kindred spirit, and although their faith on their Party leader had been badly shaken, they still preferred him to radical alternatives. Most alienation came from the Radicals, who focused their rage on Seward as a “paralyzing influence” who “kept a sponge saturated with chloroform to Uncle Abe’s nose.”

A caucus of Republican Senators took a vote for a resolution calling on Lincoln to remove Seward, which failed thanks to the objections of moderates. The caucus intended to carry their demands to Lincoln anyway, but before that Senator Preston King slipped to confer with his old friend. Seward declared that “They may do as they please about me, but they shall not put the President in a false position on my account”, and wrote his resignation, which King delivered to Lincoln. The anguished President, “With a face full of pain and surprise” asked King what the resignation meant. Lincoln was quick to recognize that Radical wrath was in truth an attempt to wrestle power away from his administration, which radicals like Senator Grimes characterized as a “tow string” that had to be bound up “with strong, sturdy rods in the shape of cabinet ministers.” The secretary they had in mind was Salmon P. Chase, who for months had claimed that “there was a back stairs & malign influence which controlled the President” and prevented more radical measures.

The Radicals then expanded their scope by demanding a “partial reconstruction of the cabinet” in a resolution that commanded unanimity within the Republican caucus. They then sent a “Committee of Nine” to present their demands. Orville Browning, one of the few Senators still loyal to Lincoln, visited the President and found him in great distress. "What do these men want?", Lincoln asked. "They wish to get rid of me, and sometimes I am more than half disposed to gratify them. . . . We are now on the brink of destruction. It appears to me that the Almighty is against us and I can hardly see a ray of hope." But the President was able to pull himself together, and he called for a Cabinet meeting of every Secretary except Seward at the same time as his reunion with the Senatorial Committee. He then asked every Cabinet member to say “whether there had been any want of unity or of sufficient consultation.”

This put Chase, the source of many malignant rumors against Seward, on the spot. As Donald explains, “If he now repeated his frequent complaints to the senators, his disloyalty to the President would be apparent. If he supported Lincoln’s statement, it would be evident that he had deceived the senators.” Chase finally had to support the President, which constituted a blow against his Radical allies. “He will never be forgiven by many for deliberately sacrificing his friends to the fear of offending his and their enemies,” said the offended Senator Fessenden. Chase then proceeded to offer his resignation too, which the triumphant Lincoln seized at once, exclaiming “this cuts the gordian knot!”. Indeed, now the Radicals couldn’t force Seward out without losing Chase. The President thus had asserted his leadership and warded off this political challenge, showing that Congressional Republicans could not simply dictate what course he ought to take. As he told Browning, “he was master, and they should not do that.” Later, he explained that in managing to gain the begrudging respect of the Radicals and the genuine allegiance of the Moderates, Lincoln was now able to ride for he had a ”pumpkin on each of my bags”.

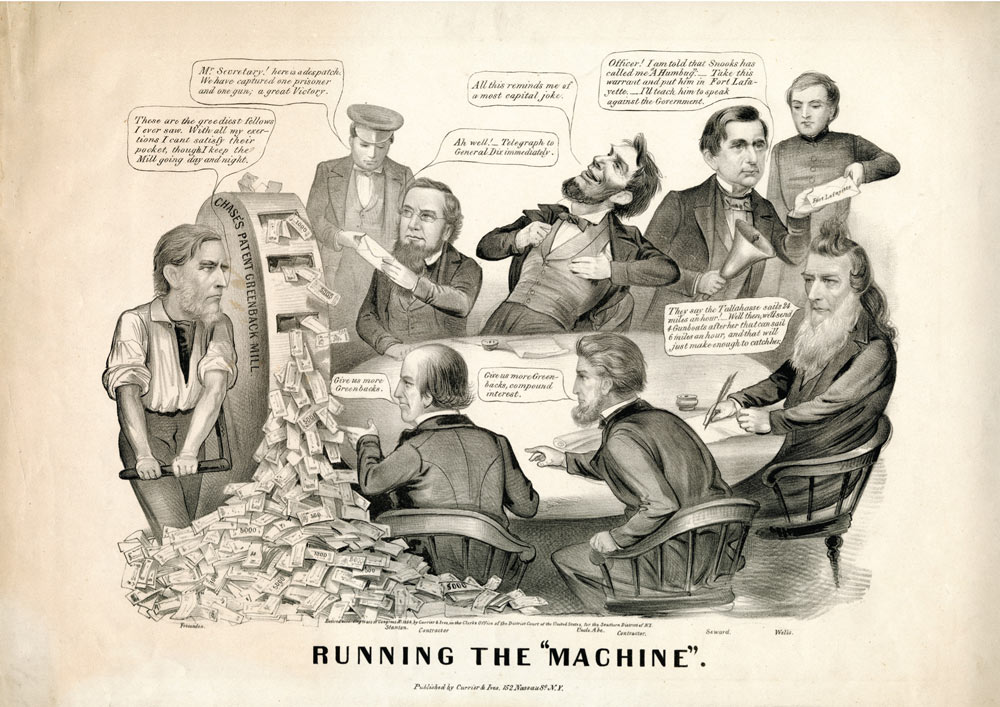

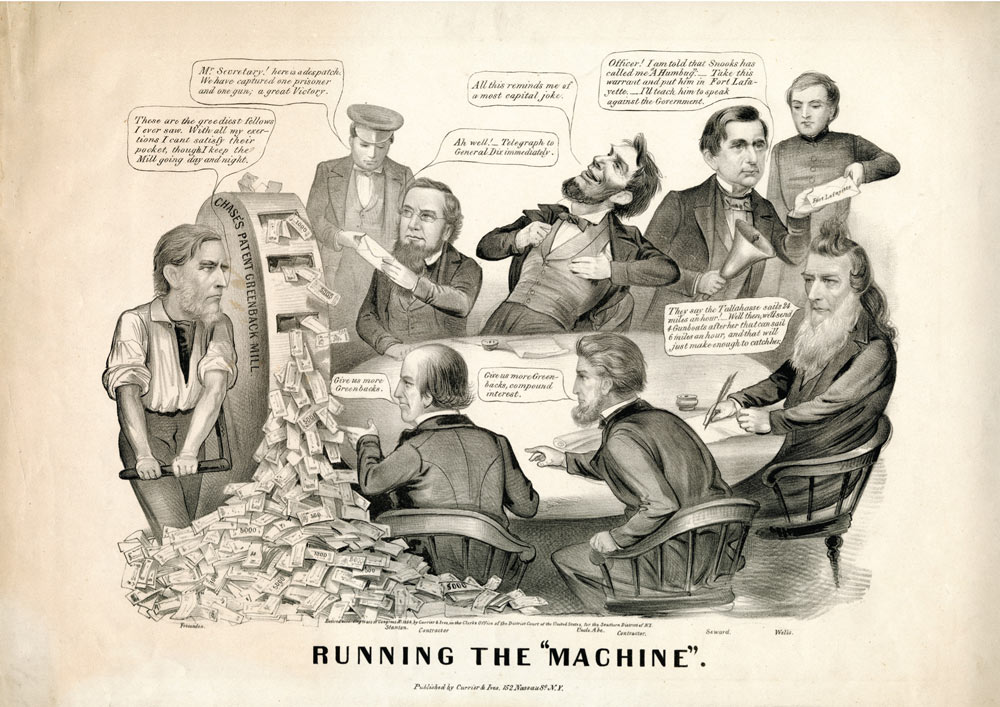

A Copperhead Political cartoon that encompasses several of their criticism of the President's government

Though Lincoln had been able to ward off political threats to his leadership of the war from both Copperheads and Radicals, the President recognized that his administration was still imperiled as long as military victories were not achieved. As he told a friend, “On the progress of our arms, all else chiefly depends”, and this was truer than ever in those trying months. As Lee set forth in his invasion of Pennsylvania and Reynolds advanced to meet him on the field of battle, everyone was conscious that more than simple victory was riding with the Army of the Susquehanna: the very survival of the Republic was at stake.

Perhaps more threatening than even Lee’s rebels were the Copperheads. So Lincoln confessed to Charles Sumner, saying that he feared more “the fire in the rear” than battlefield reverses. After the War Unionists were discredited and wiped off in the 1862 midterms, Peace Chesnuts known as Copperheads took over the Party and transformed it into an organ of anti-war unrest. Cut off from political power due to “this most disastrous epoch” that started with the 1858 midterms and made the Republicans the dominant political force in the North, Copperheads were forced to express their opposition to the war and to the Lincoln administration’s policies through violence, fraud and agitation. Emboldened by the latest military setbacks and by a strong racist backlash, Copperheads started a campaign of resistance that almost sunk the Union during the months following the Peninsula disaster.

The Copperheads’ most frequent charge was, of course, that Lincoln had set aside “the war for the Union” and in its place “the war for the Negro was begun.” The Copperheads argued openly that the war was a result of Republican fanatism, and that secession was a justified response to abolitionist attacks. The continuation of the war was just a result of Lincoln’s stubborn intransigence, and dropping emancipation as a war goal would be enough for hostilities to cease and constitutional reunion to take place. As Clement Vallandigham proclaimed, “In considering terms of settlement we [should] look only to the welfare, peace, and safety of the white race, without reference to the effect that settlement may have on the African."

Vallandigham was one of the most conspicuous Copperheads. The Ohioan had been the protagonist of a political drama in 1856, when he alleged that voting fraud had cost him a House seat. A House committee filled with Douglas Democrats took his side eventually, but the question was rendered moot when he lost the seat anyway in the 1858 Republican wave. Again, Vallandigham cried fraud, and evidence of scheming by the Buchanan Democrats lend credence to these claims. The result was that Vallandigham became something of a martyr of the Douglas-Buchanan feud, and he knew to exploit this by becoming one of Douglas’ staunchest supporters in his feeble 1860 campaign. The start of the war and Douglas’ triumphant comeback had served Vallandigham well, though even at that point he expressed a worrying sympathy with the South. After the Copperhead takeover, Vallandigham became the leader of the pro-peace faction.

Clement Vallandigham

The war, Vallandigham asserted in a speech before a large Ohio crowd just a few days after the Battle of Bull Run, had resulted in nothing but "defeat, debt, taxation, sepulchres . . . the suspension of habeas corpus, the violation . . . of freedom of the press and of speech . . . which have made this country one of the worst despotisms on earth for the past twenty months." “The dead of Manassas and Vicksburg” showed that attempts at forcible reunion had only resulted in “utter, disastrous, and most bloody failure.” The South could not be conquered, and Lincoln’s only option was to “Withdraw your army from the seceded States” and start negotiations for an armistice. Emancipation could not and should not be demanded as a precondition of peace, because there was “more of barbarism and sin, a thousand times, in the continuance of this war . . . and the enslavement of the white race by debt and taxes and arbitrary power”.

It's evident that aside from the old issues of Emancipation and what the objective of the war ought to be, the opposition adopted the new issues of martial law, military arrests, and conscription as rallying cries. Just like in the South, conscription had caused widespread discontent with the government and outright defiance in many occasions, as men reluctant to take place in a seeming failure of a war sought to escape the draft by any means, including violence. The Enrollment Act of 1863, passed shortly after the New Year, was similar to its Confederate counterpart in that its primary objective was to stimulate volunteering, but the law worked with “such inefficiency, corruption, and perceived injustice that it became one of the most divisive issues of the war” and a focal point of resistance to the Lincoln government.

The Enrollment Act, like other pieces of war-time legislation, was revolutionary in its nationalizing spirit, for the draft would not be conducted by the individual states but directly by the War Department. Stanton and his corps of Provost Marshals enforced it with the ruthless efficiency that characterized the Secretary, but unfortunately not even the incorruptible Stanton could assure complete honesty in the entire process. Individuals failed to report when their names were drawn from the lottery, skedaddling to swamps or other countries. Or they bribed officials to report a false dependency by an orphan child. Prostitutes were hired to pretend to be an indigent mother who pleaded for “her” son to remain home. Some feigned illness or injury, or bribed medics to declare them unfit for duty. One Doctor Beckwith even unabashedly sold certificated of unfitness for $35 dollars. If that failed, some men went as far as mutilating themselves, by cutting off fingers or pulling teeth.

Conscription was such an explosive issue because for many Northern communities it was the first time they had truly felt the hard hand of war. The parades of 1861 had of course left an indelible mark in the memory of thousands, but those were young idealists who volunteered for a war they thought would be short and glorious. It was completely different for “a young man to be torn from his farm and family” to fight in a conflict that seemed hopeless at the moment. “Few issues affected the home front so directly”, comments Donald Dean Jackson, “and few so severely tested the North's resolve to act as a nation”. Alexis de Tocqueville had once declared that "the notions and habits of the people of the United States are so opposed to compulsory recruitment that I do not think it can ever be sanctioned by their laws." This was now to be tested.

An aspect of the law that increased resistance to it was the fact that both volunteers and draftees would be assigned to existing regiments. During the original call for volunteers, the desire to serve with neighbors and friends and the pride of fighting in a unit named after one’s hometown had served as effective means of stimulating volunteers. Now, it was clear that green troops would perform better if aided by veterans. The need was further underscored by the simple if grim fact that many units only existed in paper, two years of war having resulted in their almost complete extermination, leaving on their wake entire towns “where only women, children and the elderly” remained. This was not without its consequences, for many veterans regarded the new conscripts with contempt, saying that "Such another depraved, vice-hardened and desperate set of human beings never before disgraced an army," and characterizing them as "bounty jumpers, thieves, roughs and cutthroats".

Civil War Conscription

It can be discerned from these statements that special contempt was reserved for the so-called “bounty-jumpers”. The term referred to men who claimed bounties offered by the Federal government or local jurisdictions, only to then desert and claim another bounty. The practice of offering such bounties started with the war, as a way of offering subsistence to homes that lost their breadwinners. But as war fever ebbed and the need for fresh recruits increased, the sums offered started to climb as well – and with them the potential for fraud. After the Enrollment Act was passed, bounty jumpers were able to make easy fortunes by claiming several bounties or offering themselves as substitutes several times. One Connecticut youth, for example, sold himself for $300 and then bought a substitute for $150. “Substitute brokers” went into business as a way of obtaining the highest possible bounties for their clients, and insurance firms started to offer “draft polices” that gave from $300 to $500 so that clients could hire a substitute if drafted.

Substitution, as said in earlier chapters when Confederate conscription was discussed, had such deep roots in European and American military history that its inclusion was not questioned. This did not stop charges of “a rich man’s war, a poor man’s fight”, as the soaring price of substitutes meant that only the well-off could contract them, while the poor man would inevitably end up in the army. Around a little Vermont town, the price of substitutes rose to over 900 dollars, while Cortland practically bankrupted itself by paying for substitutes to “preserve the unity of families intact and snatch unwilling victims from the moloch of war”. “The Rich are exempt!”, cried an outraged Iowa newspaper.

Originally, Republican lawmakers intended to include a 300 dollars commutation fee as a way to cap the price of substitutes and put it within the reach of the poor. So said Senator Wilson, who believed that the law ought to “throw a dragnet over the country and take up the rich and the poor and put the burden upon all." The commutation fee would also work similarly to Southern occupation exceptions, by keeping those valuable to the war effort on the home-front. But the outcry against “blood money” was so severe that Republicans decided to not include the $300 dollar fee, instead creating a series of exceptions that included not just respectable white-collar occupations like telegraph operators, teachers, clergymen and clerks, but also some common occupations like firemen, miners or industrial laborers. Racial resentments were also soothed by the fact that Black men were also liable for conscription, though it was limited to free people for the moment.

The draft produced extremely bitter and partisan denunciations by Copperheads who saw conscription as “an unconstitutional means to achieve the unconstitutional end of freeing the slaves”. A Pennsylvania lawmaker denounced the law as “unconstitutional, unjust, unjustified,” and a Chesnut convention pledged to “resist to the death all attempts to draft any of our citizens into the army”. These pledges were not merely words, for communities were ready to resort to violence to preventing conscription from taking place. In Wisconsin, eight companies of troops had to be summoned after a mob carrying a banner that said “No Draft!” murdered an enrollment officer, and two others shared this unhappy fate in Indiana. A Pennsylvania officer received a threatening letter: "If you don't lay aside the enrolling, your life will be taken tomorrow night”. More officials forms of resistance abounded too. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court produced a ruling that declared the draft unconstitutional (the government ignored it), and even the Republican Governor of New Hampshire warned that the draft could only be enforced in his state with the presence of an infantry regiment.

The greatest basis of opposition, of course, came from the Chesnuts, who used their favorite weapon to great effectiveness. Emphasizing the point that the draft would force White men to fight for Negro emancipation, Chesnut politicians and newspapers denounced conscription in racist terms. An editor told a Catholic meeting that the President “would be dammed if he believed they would go and fight for the nigger,” while a Chesnut speaker said that slave emancipation would bring thousands of freed Blacks to "fill the shops, yards and other places of labor" soldiers had left behind, thus forcing “the poor, limping veteran” to “compete with them for the support of our families." Samuel S. Cox said that the real cause of the war was the "Constitution-breaking, law-defying, negroloving Phariseeism of New England" A National Unionist meeting resolved they would fight for Uncle Sam, “but never for Uncle Sambo”. Class tensions and racism were reinforced by diverse incidents, like in New York, where striking Irishmen were replaced by Black laborers.

Throughout the North there were many outbreaks of anti-draft resistance

In the face of such resistance, the Lincoln administration once again took extreme measures to enforce the draft. To prevent judges from issuing writs of habeas corpus to free conscripts, he suspended the writ nationwide once again, and authorized the arrest of anyone who discouraged enlistment or engaged in other kinds of “disloyal practices”. This included the arrest of disloyal newspapers, and some people apparently even began to carefully consider what they said in personal letters. A Chesnut Senator charged that through these actions Lincoln was “declaring himself a Dictator, (for that and nothing less it does)”, and reports of men jailed merely for “hurrahing Johnny Breckenridge” abounded. War Unionists had been willing to accept such arrest during the first months of the war as a way to stamp out treason in the Border South. “I grant, sir, that there was a time when anarchy and confusion reigned in the Border Slave States” and such arrest were necessary, declared one of them. But “that there can be no such justification, no palliation, no excuse”, for arrests in “the loyal states of the North” far from the frontlines.

On February 15th, the War Department issued a series of infamous regulations that allowed military commanders “to arrest and imprison any person or persons who may be engaged, by act, speech, or writing, in discouraging volunteer enlistments, or in any way giving aid and comfort to the enemy, or in any other disloyal practice against the United States”. A series of sweeping arrests followed. In those feverish months were the very fate of the Union seemed at stake and scared Unionists saw treason and butchery in any corner, the scenes in several Northern communities approached those of the French Revolution, with mere accusations being enough to have someone arrested. Mark E. Neely condemns these events, arguing that the February orders, called mockingly “Lincoln’s 14 Frimaire” by opposing Chesnuts, “showed the Lincoln administration at its worst—amateurish, disorganized, and rather unfeeling.” Altogether, almost a thousand men were arrested during the period of February to May 1863.

In reaction to these events, Chesnuts from all over the country denounced Lincoln as a “despot . . . who disregards the Constitution in the name of fanatism” and prosecuted a war “for the benefit of Negroes and the enslavement of Whites”. Horatio Seymour, the defeated 1862 candidate for the New York Governorship, said that emancipation was “bloody, barbarous, revolutionary" and that he would never accept the doctrine that that the loyal North lost their constitutional rights when the South rebelled.” Representative Cox, an Ohioan like Vallandigham, charged Lincoln with taking actions “unwarranted by the Constitution and laws of the United States”, which constituted “a usurpation of power never given up by the people to their rulers.” The New York Atlas attacked “the tyranny of military despotism” and “the weakness, folly, oppression, mismanagement and general wickedness of the administration at Philadelphia.” A common denunciation was that the law was most commonly employed against Chesnuts as a way of getting rid of political opponents. One woman, for example, denounced that Union soldiers broke into her home in the middle of the night and took away her husband. His crime was simply attending a National Union convention.

Lincoln justified these actions by declaring that in a civil war such as the nation faced, the entire country constituted a battlefield. He insisted that it was necessary to arrest those “laboring, with some effect, to prevent the raising of troops [and] to encourage desertions”, for they were “damaging the army, upon the existence and vigor of which the life of the nation depends”. Conducting such actions in the North was justified, for "under cover of 'liberty of speech,' 'liberty of the press,' and Habeas corpus,' [the rebels] hoped to keep on foot amongst us a most efficient corps of spies, informers, suppliers, and aiders and abbettors of their cause." The suspension of civil liberties, Lincoln concluded, was “constitutional wherever the public safety does require them.” Using a “homely metaphor”, the President promised that such excesses would not continue in peace-time, and arguing that they would was like saying “that a man could contract so strong an appetite for emetics during temporary illness, as to persist in feeding upon them through the remainder of his healthful life.”

These arguments, published on the New York Tribune, were accepted by Republicans who had entered into a crisis mode. As in other revolutions and wars, the people craved strong government and decisive action in order to protect their safety and assure ultimate victory, and this helps explain why the North was willing to accept such flagrant violations of civil rights. The overarching reason was, naturally, news of rebel atrocities in the South, which caused such a political polarization in the North that soon enough everyone who did not support the Union was accused of treason and of being in favor “of the butchery of women and children and the total extermination of the Union men of the nation.” The people did not merely welcome Lincoln’s actions, but took justice in their own hands in order to suppress any perceived treason, freely using intimidation and violence.

Political opponents were charged with being supporters of the rebellion and their atrocities

In Ohio, an editor was stopped from publishing an anti-war article after a mob appeared before his house with a guillotine, emblazoned with the message “the remedy for treason.” A Massachusetts editor was less lucky, for after he criticized the government a mob formed outside of his house. Accusing him of being in favor of “rebel marauders”, the mob seized him and gave him a coat of tar and feathers before exiling him from the town. An anti-war orator was shot when he dared venture into an Indiana town that had suffered a rebel raid, the townsfolk crying that it was the fault of traitors like him that the war continued. Deserters and draft dodgers were shamed and shunned by their peers. The story of a young man who was given a dress by his sweetheart after he refused to enlist seems quaint when compared with the stories of a Pennsylvania town were fears of rebel invasion had whipped the people into a frenzy. There, draft dodgers were marked with the letter “T” by people who said they wanted to aid the rebels in their rapine and massacre, and one deserter was tied to a tree and set in fire.

Just like how Chesnuts accused African Americans of being the cause of the war, Republicans started to accuse Copperheads of being the cause of the latest failures. A year ago, one editor had asked why the 20 million loyal people of the North hadn’t been able to overcome 5 million rebels; now, a Radical editorial offered an answer: “The fault lies in every wiley agitator, who encourages desertion and cowardice, and . . . enter into intrigues with rebels to assure our defeats.” Indeed, McClellan had been a National Unionists, hadn’t he? And Vallandigham was encouraging desertion even as Lee advanced into Pennsylvania, whose people were afraid of suffering like the Kansans and East Tennesseans had. If the National cause was to be victorious, any such show of disloyalty had to be trampled and exterminated, until only “true Union men” were in charge. A horrified man interrupted a speech given to this effect by predicting rivers of blood and terror far beyond the worse Jacobin excesses. The speaker, to enormous cheers, replied that “if scaffolds and guillotines from the Susquehanna to the Rio Grande be needed to preserve this temple of freedom, I say, let it be done.”

Accordingly, Copperheads suffered abuse and violence at the hands of Radicals who blamed them for military reserves and war atrocities. When a Copperhead advocated for resistance to the draft, a mob of women formed to confront him. They said that many of their husbands had fallen in battle for lack of support in the Homefront, and that “traitors such as you, sir, are the direct cause of such want of morale and men” in the battlefield. The women proceeded to tar and feather the man, and when another man tried to intervene, they hit him with bricks and sticks, giving him a severe concussion. A similar but even worse fate befell a peace speaker who was confronted by Union soldiers in furlough. They all had lost comrades in rebel raids, and, enraged by “this open advocacy of treason at our very homes”, they attacked him, breaking his arm and leaving him bleeding from a head wound. Copperhead newspapers were attacked and burned to the ground, and “Union League” militias broke National Union conventions.

These lamentable events reflect the developing of an “us vs them” mentality that meant that anyone that did not support the war and the government was a traitor who cheered for rebel murderers. One Republican congressman so complained, saying that he did not endorse “Lincoln’s Robespierrean campaign”, but that if he voiced such opposition he would be heckled as being a traitor and treated as if he were “personally responsible for the latest rebel outrages.” Some political “purges” took place as people who did not support the war’s prosecution were charged with being for disunion. One Republican was forced to vote for a bill empowering Lincoln to suspend Habeas Corpus. He at first fretted that he would not win reelection, but a colleague dispelled these fears: “Reelection? You’d better get your nomination first. Haven’t you learnt that it is the Radicals who do that job nowadays?” A moderate Republican was accused of being a Copperhead by a mob that fierily declared they could forgive rebels, but never a Copperhead. Intimidated by their presence, the politician was forced to call for Breckenridge to be hung from a sour apple tree before the mod dispersed.

Union Leagues and Loyal Publication Societies began to spring throughout the North, carrying stories of rebel atrocities and interviews with people who suffered under their rule or their raids. The Republicans were not above extralegal or even outright illegal actions in order to assure victory. Indiana’s Governor, Oliver P. Morton, convinced the Republicans in the National Union legislature to withdraw, preventing a quorum. Forced to run the state without the usual appropriations, Morton borrowed from banks and received $250,000 dollars from the War Department. An attempt to do likewise in Illinois, where very slim Republican majority in the Legislature ruled alongside the radical Governor Yates, failed because Federal troops arrested National Unionists and held them forcibly in the Legislative chambers for some important votes. Accused then of dereliction of duty, they were forced to resign their seats and were promptly replaced by Republicans in elections where fraud was alleged.

Oliver P. Morton

Extralegal actions were also taken to prevent the Governorships of Connecticut and New Hampshire from falling into Copperhead hands. The War Department furloughed Connecticut soldiers (and some, it’s said, from other states as well) to allow them to go home and vote the Republican ticket. Widespread violence and fraud were reported, as Union League paramilitaries guarded the ballot boxes. Anyone seen as sympathetic to the Copperheads was prevented from voting, and a woman who leaned towards the Radicals talked of “a glorious campfire made with the votes of traitors.” In New Hampshire such methods were not required due to a third candidacy by a War Unionist, who split the anti-Republican vote. The election was thrown to the Republican legislature which, obviously, elected their man.

This split is emblematic of a deeper division within the National Union. The main division was, of course, between War Chesnuts and Copperheads. Since both camps were committed to reunion and opposed to the Lincoln administration, an alliance was easy to maintain as long as those twin goals were maintained. But as the war degenerated into a desperate struggle that would see one side victorious and the other completely defeated, it became obvious that reunion could only be effectuated by a complete triumph over the enemy. Thus, a new division between the Peace Chesnuts who only accepted peace if it came with reunion, and the Copperheads, who considered war and abolition such great evils that they were willing to accept disunion. It’s dubious that all Chesnut were willing to accept this, but in the face of such political polarization and with Northerners worried about their very survival, any pro-peace sentiment was denounced as disunionist and treasonous, and advocacy for massacre and rapine.

This was a conundrum for Douglas Chesnuts who followed his maxim of country over Party and rejected partisan attacks in favor of a crusade for the Union. Some, of course, had been alienated by emancipation and the new radical measures. But as Copperheads came to accept disunion as the price for peace, the question for these War Chesnuts became whether they were willing to accept abolition as the price for Union. Some, such as Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, did so. More astoundingly, there were men like Benjamin Butler, who had supported Buchanan and Breckenridge and was now well on the road to become a Radical Republican. Complicating matters was the lack of coherence and unity of purpose of the National Union. Formed by Douglas as a popular sovereignty party, it had crashed disastrously in 1858 and 1860, and even in 1863 it was unable to find a coherent basis of opposition or command loyalty to the party itself.

The rebels themselves shot down Copperhead hopes of peaceful reunion by their demands for Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky and their terrible acts of terrorism against Unionists. Vallandigham, conferring illegally with Confederate agents in Canada, pushed forward for reconciliation, and asked them for support in a campaign for the Ohio governorship, promising that "the peace party of the North would sweep the Lincoln dynasty out of existence." The Confederate agents replied that he was “badly deluded”, and in response Vallandigham said that they would be open to recognizing Confederate independence if they refused to come back. A Union spy recorded these conversations and leaked them to the press, where the Union League took care that they were spread far and wide to both show that Copperheads were traitors and also that War Chesnuts had only two options: peace and disunion, or war and Union.

The portrait of the Copperheads as just another set of traitors took special importance when news of treasonous conspiracies in the Midwest and New York started to be reported. In New York, there were widespread rumors “of a purpose by the local Copperhead population to raise in insurrection” at the same time as Lee’s invasion, in order to assure a Confederate victory. Curiously enough, there apparently was not a great reaction to these reports, which leads one to suspect that they were created later with the benefit of hindsight. Rumors of plans for the formation of a Midwest Republic that would conclude a separate treaty of peace and perhaps even join the Confederacy abounded, and caused greater fears at the time.

Reports of dealings between Copperheads and rebels stiffened the resolve of the Republicans

Besides the racism that sadly characterized the region, Midwestern resentment was partly a result of economic grievances. The Mississippi was still closed, and the mighty river had been the main venue of commerce and transport of these states previous to the war. Now they had to rely in railroad commerce with the East, which they frankly saw as degrading. An Ohio editor went as far as saying that the region would "sink down as serfs to the heartless, speculative Yankees”, after being “swindled by his tariffs, robbed by his taxes, skinned by his railroad monopolies." “The rising storm in the Middle and Northwestern States,” a loyal Illinois man predicted, would cause “not only a separation from the New England States but reunion of the Middle and Northwestern States with the revolted States.” Already alarmed Republicans started to see “Treason... everywhere bold, defiant—and active, with impunity!”.

News of complots like this one and of prominent Copperheads conferring with rebel agents increased the perception of the National Union as just “another organ of the Breckenridge insurrection” and their speakers as people employed directly by Richmond. Republicans started to see in fevered nightmares a future where the Confederacy had taken not only the Border States but the Midwest and Pennsylvania and engaged in the extermination of all loyal men there. Copperhead support for unconditional peace and Republican pushes for unconditional victory put Conservative Republicans and War Chesnuts in a very uncomfortable condition. “What am I to do”, one of them lamented, “on one side there are the abolitionists and their radical objectives, on the other there are traitors, defeat and dishonor.” Some Republican conservatives would have surely deserted their party had the opposition been more moderate. Instead, they found themselves in the company of “traitors and Copperheads”. Unable to accept this, most remained in the Republican fold, even if reluctantly.

Some pinned their hopes in the creation of a grand conservative party that would limit itself to “the constitutional prosecution of the war” a scheme that men like Horatio Seymour, Thurlow Weed and even Lincoln himself at times seemed to favor. But if the National Union coalition was floundering due to divisions between pro-war and pro-peace faction, the differences between Republicans and Chesnuts were much more fundamental and much more severe, and they precluded any attempt to form such a coalition. The accusation that people who did not support the Administration were Copperheads and the violent actions taken to suppress them also forced many to choose. ‘There are few journals in this city in whose columns, during the present civil war, can not be found invocations to violence against dissentients from their opinion”, bemoaned Samuel J. Tilden. The result was that opposition to the Lincoln administration remained incoherent, divided and weak, unable to present a united front.

This was very fortunate for Lincoln, for a more competent opposition might have been able to force him out at that time of crisis. As things were, he was barely able to resist sagging civilian morale and challenges to his leadership from his own party. “Failure of the army, weight of taxes, depreciation of money, want of cotton . . . increasing national debt, deaths in the army, no prospect of success, the continued closure of the Mississippi [River] . . . all combine to produce the existing state of despondency and desperation”, said the Chicago Tribune, adding that “the war is drawing toward a disastrous and disgraceful termination.” Harpers Weekly declared that the people "have borne, silently and grimly, imbecility, treachery, failure, privation, loss of friends, but they cannot be expected to suffer that such massacres as this at Bull Run shall be repeated”. A Maine soldier wrote home that “the great cause of liberty has been managed by Knaves and fools. The whole show has been corruption, the result disaster, shame and disgrace.”

Even some Republicans were now willing to accept peace. A soldier confessed that "my loyalty is growing weak. . . . I am sick and tired of disaster and the fools that bring disaster upon us. . . . Why not confess we are worsted, and come to an agreement?" The erratic Horace Greeley, who swung from radical demands of emancipation to loud yelps for peace depending on battlefield fortunes, even proposed a hare-brained scheme for peace that involved an offer of mediation by Napoleon III. Greeley’s action so offended Seward that he threatened to have him indicted under the Logan Act, but they do reflect Northern despondency. "Our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country," he wrote, "longs for peace—shudders at the prospect of terrible conscription, of further wholesale devastations, and of new rivers of human blood."

Many Republicans blamed Lincoln for the course the war had taken. They accused him of being a “half-witted and incapable idiot”, even intimating that his “secesh wife, the Traitoress Mrs. Lincoln” had prevented a vigorous prosecution of the war. Minnesota’s Senator Wilkinson would declare that there was no hope “except in the death of the President and a new administration.” Former Justice Samuel Curtis found that most Republicans agreed on “the utter incompetence of the Pres[iden]t . . . He is shattered, dazed and utterly foolish.” A Michigan representative thought Lincoln “so vacillating, so week [sic] ... so fearful... and so ignorant... that I can now see scarcely a ray of hope left.” Richard Henry Dana Jr. found “the most striking thing is the absence of personal loyalty to the President. It does not exist.” Wild rumors circulated in Philadelphia, saying that the entire cabinet would resign and be replaced by War Chesnuts or even Copperheads, or that Frémont or Butler would be called to act as dictator, or that Radical Republicans planned to depose Lincoln and create a Revolutionary Directory to rule the country.

William Pitt Fessenden

Much talk was focusing on bitter recriminations against the Cabinet. Moderates charged Stanton and Chase were malign influences that were pushing Lincoln to radical measures, but moderates had also been pushed towards radicalism as a result of Southern atrocities. “Go and vote for burning Churches, raping women, and massacring Union men”, Senator Wade goaded, “or vote with the Chesnuts, which is the same thing.” They still felt uncomfortable with the prospect of a crusade for abolition and the complete destruction of the South, but were much more willing to accept hard war measures as a reaction to Southern terror. They recognized in Lincoln a kindred spirit, and although their faith on their Party leader had been badly shaken, they still preferred him to radical alternatives. Most alienation came from the Radicals, who focused their rage on Seward as a “paralyzing influence” who “kept a sponge saturated with chloroform to Uncle Abe’s nose.”

A caucus of Republican Senators took a vote for a resolution calling on Lincoln to remove Seward, which failed thanks to the objections of moderates. The caucus intended to carry their demands to Lincoln anyway, but before that Senator Preston King slipped to confer with his old friend. Seward declared that “They may do as they please about me, but they shall not put the President in a false position on my account”, and wrote his resignation, which King delivered to Lincoln. The anguished President, “With a face full of pain and surprise” asked King what the resignation meant. Lincoln was quick to recognize that Radical wrath was in truth an attempt to wrestle power away from his administration, which radicals like Senator Grimes characterized as a “tow string” that had to be bound up “with strong, sturdy rods in the shape of cabinet ministers.” The secretary they had in mind was Salmon P. Chase, who for months had claimed that “there was a back stairs & malign influence which controlled the President” and prevented more radical measures.