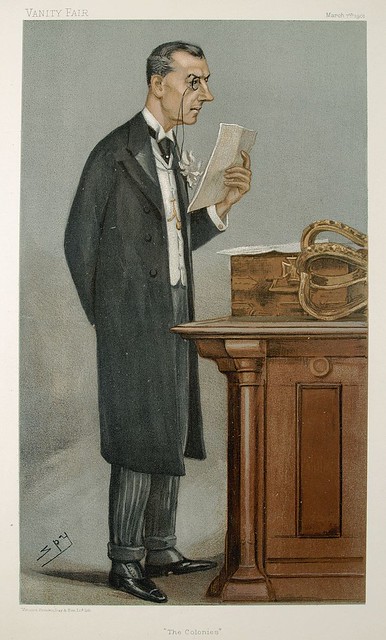

After succeeding Salisbury in autumn 1900, Lord Lansdowne held the post during the eventful first five years of the century. An old Etonian who had also studied at Balliol, Lansdowne had risen to a position of eminence despite his early age, becoming the governor-general of Canada at 38 and a Viceroy of India at 43. Because his extensive holdings in Ireland oriented him to the Conservative Party, Salisbury had put his administrative experience to good use. “

I shouldn’t call him clever, he was better than competent”, as Arthur Balfour described his limited, but flexible approach. He had undoubted industry, shrewdness and capacity for understanding complex international situations. Willing to compromise, accept advice and suffer temporary setbacks and defeats without losing his balance, he was an excellent negotiator. His lack of brilliance was in fact often an advantage when he sought

motus vivendi with the other Great Powers of the day.

Extensive prior experience of international and colonial problems had led him to believe that foreign policy should be consistent, “

lifted out of party politics and placed on a different plane.” Naturally a small élite of landed aristocracy was best qualified to safeguard this secretive world of diplomacy and national defence. Chamberlain reserved the posts of foreign and defence opposition speakers to a small inner circle of former ministers: out of 12, nine were peers or sons of peers, and eight were old Etonians.

Widely criticized for his administration of the War Office as the Secretary of War at the start of the Boer War, Lansdowne and his colleagues watched the postwar world with the firm conviction that traditional British isolationism was no longer feasible. To meet threats from some Great Powers they would have to seek agreements with others, to balance them against one another.

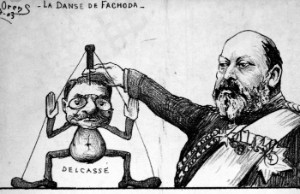

The end to the exploration of possibilities with Berlin in 1902 for the time being was not tragic to Chamberlain and Lansdowne, who were aware of the relative security of Britain. Both men understood the difficult geopolitical position Germany faced. Unlike Chamberlain, Lansdowne never saw the need to turn his back entirely to the possibility of an agreement. To make concessions where possible and signal strength as required by essential interests of Britain - for him, the old maxim remained tried and true.

He leaned heavily on the Permanent Under-Secretary Sanderson, one of the few old hands who could recall the mid-Victorian period and the one who had accompanied Lord Salisbury during most of his career. He alone remembered the obscure background and details of such vital international treaties as the Mediterranean agreements, and kept the original texts in his office.

In May 1901 Sanderson formulated the draft of the proposed Anglo-German defensive alliance for Chamberlain. He included a short note summarizing the difficulties of a project which he did not favour. On the German side Baron Eckardstein and the ailing German ambassador Count Hatzfeldt were fighting a diplomatic duel that further complicated matters. But Sanderson was not without sympathy: “

Germany is a young power, striving for recognition as a world influence. It was inevitable that she should emulate the British and have colonial aspirations. It was unfortunate that everywhere Germany wished to expand, she will find the British lion in her path.” He remarked that despite this a policy of one-sided concession was foolish and impossible. Britain had so far been more tolerant towards German colonial aspirations, because they had been considered less threatening than those of France or Russia.

But the Germans had mistook the British attitude as a sign of weakness rather than of strength. Regardless of their folly, the German sensitivities should still be respected, and her expansion not checked where it did not clash with major British interests. As a man of an era when there were still large areas in which to manoeuvre, Sanderson still recalled the times when colonial disputes still determined the relations of the Great Powers.

Having observed the cyclical movement of the state system for more than four decades, he appeared far more unsettled by the perceived

weakness of the Central Powers, particularly Germany, than by their supposed bid for world dominance and aggression. For Lansdowne and Sanders, the ebb and flow of the Anglo-German relations and even the erratic Kaiser were not particularly remarkable. Holstein and Eulenburg were neither to be taken too seriously, nor was a war between the two countries deemed inevitable. Repeatedly they sought to imagine themselves in the position of their colleagues in Berlin. Balfour commented that Germany repeatedly seemed to ignore good opportunities to realize the hegemonial plans that Berlin was accused of harbouring.

For his side, Lansdowne saw the world where heavily armed Great Powers formed and reformed combinations with and against each other with the utmost rapidity. He sought to avoid the conflict that might arise for Britain as a result. What others called muddling through with ad hoc diplomacy was a conscious policy that gave Britain room to maneuver, provided flexibility, and sought to stabilize the state's system by keeping it in flux. For if separation of Empire and the continent were abandoned, especially in dealings with Russia, colonial tensions would automatically be reflected back to Europe, where they risked intensifying into existential crises. British diplomacy had be conducted with a clear vision and subtle tact to avoid such calamities.

Lansdowne was willing to pay a good price for better relations with other countries, as he found the isolation of Britain alarming, and was anxious to reduce imperial commitments in the far corners of the globe. Convinced that Britain was suffering from imperial overreach, he sought to reduce British exposure to risk, at the very least seeking to lower the intensity and scope of such conflicts as might inevitably occur. He sought continental friends, not foes. To this end, he downplayed both perceived and actual dangers.