Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists

The unlikely alliance between the Sauds and Wahhabism - a nomadic desert tribe and an ultra-Conservative Islamic - sect had survived wars, invasions, civil war and subjugation to rival Arabian power before.

The alliance had grown deep roots in the historic region of Najd due to the process that had begun in the sixteenth century and lasted until the eighteenth. For centuries, tribes had moved into and out of Najd, either in search of new pastures or taking refuge from enemies elsewhere. This immigration to the region had created new settlements.

Here the Saud leadership had formed new political entities. The old traditional tribal systems had been replaced by a novel form of centralised power. It had been based on Wahhabism, and the premise of a religious revival that would salvage the people of Najd from a moral crisis.

The pursuit of this goal had been an uphill struggle, slow and unsteady at every step. But the Saudis had endured with mere persistence and fanaticism.

They relied on their reputation as primarily religious warriors, unlike the other chieftains who fought more concrete goals.

Under the Wahhabi banner the House of Saud had periodically challenged the Ottoman rule since the eighteenth century, always failing to gain lasting autonomy, but never submitting to the authority of the Ottomans either.

Their religious heritage made defiance the default option of the House of Saud. One of the key Wahhabi ideologues, Sulayman ibn 'Abd Allah ibn Muhammad - the grandson of Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab - had written a fatwa that was especially important for the Saudi Wahhabis at the turn of the century.

The fatwa instilled the importance of having loyalty to Muslims and enmity towards non-Muslims (al wala' wa al-bara'). The key point of the first fatwa was that true Wahhabis could not befriend the Ottomans or any of their allies. If they did so, then their lands ceased to be truly Islamic. The fatwa also argued that as true Muslims, Wahhabis could not even travel to the land of the idolaters (Ottomans and their allies) since even this risked contaminating their faith. True faith required open enmity towards the idolaters.

Another key Wahhabi fatwa was written the great-grandson al-Wahhab the senior, Shaikh 'Abd al-Latif. He argued that the Wahhabis had to hate and defy the idolaters (non-Wahhabis in general but the Ottomans and the Egyptians specifically) since this was divine will, and that any allegiance to them would be a clear act of apostasy.

This type absolutism was pleasing for the Wahhabi Ulama, but had not exactly been especially effective recipe for a lasting foreign policy or territorial expansion. Even the ’Ennezza, the Saudi home tribe, did not fully accept the Wahhabi creed. The desire to wage religious war had also so far failed to deliver lasting results. In fact, for the last twelve years, the last Saudi ruler of any importance had spent his days in exile. His ally, the emir of Kuwait, had been kind enough to shelter the family.

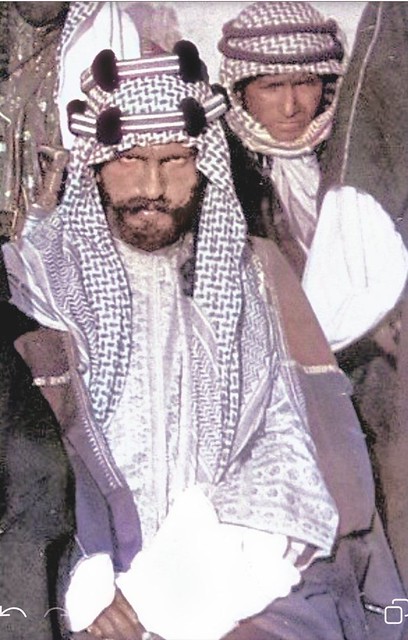

The young hope of the House of Saud, Abdulaziz ibn Abdul Rahman ibn Faisal ibn Turki ibn Abdullah ibn Mohammad Al Saud, was known as Abdul Aziz to Arabs and ibn Saud for the British.

He had always been very close to his paternal aunt, Jawhara bint Faisal. She had ingrained in him a strong sense of family destiny, and instilled a mission to regain the lost glories of the House of Saud. Well educated in Islamic lore, Arab customs and local tribal and clan relationships, Jawhara had urged her nephew to reclaim the lost Saudi lands and revive the religious struggle against the idolaters.

But in order to do so, he and the Saudis had to face the might of one of the largest tribal confederations in Arabia, the Shammar.

The alliance had grown deep roots in the historic region of Najd due to the process that had begun in the sixteenth century and lasted until the eighteenth. For centuries, tribes had moved into and out of Najd, either in search of new pastures or taking refuge from enemies elsewhere. This immigration to the region had created new settlements.

Here the Saud leadership had formed new political entities. The old traditional tribal systems had been replaced by a novel form of centralised power. It had been based on Wahhabism, and the premise of a religious revival that would salvage the people of Najd from a moral crisis.

The pursuit of this goal had been an uphill struggle, slow and unsteady at every step. But the Saudis had endured with mere persistence and fanaticism.

They relied on their reputation as primarily religious warriors, unlike the other chieftains who fought more concrete goals.

Under the Wahhabi banner the House of Saud had periodically challenged the Ottoman rule since the eighteenth century, always failing to gain lasting autonomy, but never submitting to the authority of the Ottomans either.

Their religious heritage made defiance the default option of the House of Saud. One of the key Wahhabi ideologues, Sulayman ibn 'Abd Allah ibn Muhammad - the grandson of Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab - had written a fatwa that was especially important for the Saudi Wahhabis at the turn of the century.

The fatwa instilled the importance of having loyalty to Muslims and enmity towards non-Muslims (al wala' wa al-bara'). The key point of the first fatwa was that true Wahhabis could not befriend the Ottomans or any of their allies. If they did so, then their lands ceased to be truly Islamic. The fatwa also argued that as true Muslims, Wahhabis could not even travel to the land of the idolaters (Ottomans and their allies) since even this risked contaminating their faith. True faith required open enmity towards the idolaters.

Another key Wahhabi fatwa was written the great-grandson al-Wahhab the senior, Shaikh 'Abd al-Latif. He argued that the Wahhabis had to hate and defy the idolaters (non-Wahhabis in general but the Ottomans and the Egyptians specifically) since this was divine will, and that any allegiance to them would be a clear act of apostasy.

This type absolutism was pleasing for the Wahhabi Ulama, but had not exactly been especially effective recipe for a lasting foreign policy or territorial expansion. Even the ’Ennezza, the Saudi home tribe, did not fully accept the Wahhabi creed. The desire to wage religious war had also so far failed to deliver lasting results. In fact, for the last twelve years, the last Saudi ruler of any importance had spent his days in exile. His ally, the emir of Kuwait, had been kind enough to shelter the family.

The young hope of the House of Saud, Abdulaziz ibn Abdul Rahman ibn Faisal ibn Turki ibn Abdullah ibn Mohammad Al Saud, was known as Abdul Aziz to Arabs and ibn Saud for the British.

He had always been very close to his paternal aunt, Jawhara bint Faisal. She had ingrained in him a strong sense of family destiny, and instilled a mission to regain the lost glories of the House of Saud. Well educated in Islamic lore, Arab customs and local tribal and clan relationships, Jawhara had urged her nephew to reclaim the lost Saudi lands and revive the religious struggle against the idolaters.

But in order to do so, he and the Saudis had to face the might of one of the largest tribal confederations in Arabia, the Shammar.