You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Chapter 173: Britain, Part VII: Back on Track

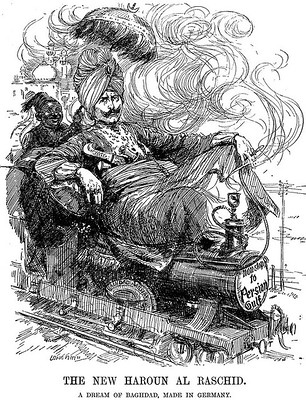

Lansdowne, a former Viceroy of India (1888-1894), made an official statement in the House of Lords debate on Great Britain and the Persian Gulf in 1903. “Our policy should be directed in the first place to promote and protect British trade in those waters...HM’s Government should regard the establishment of a naval base, or a fortified port, in the Gulf by any other Power as a very grave menace to British interests, and we should certainly resist it with all the means at our disposal." According to this policy, the German proposals for a protectorate over Kuwait and French initiatives to acquire a coaling station had been both foiled in the recent past.

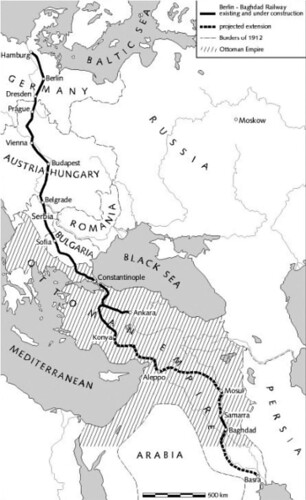

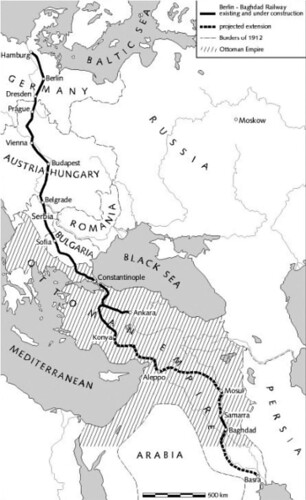

As it was, the British-Indian interests in the Ottoman vilayets of Baghdad and Basra had expanded steadily after the British shipping interests had acquired the rights of navigation on the Euhprates and Tigris after 1846. By now they controlled more than two-thirds of imports and half of exports of Basra. Eager to gain access to the the Ottoman markets, the German financiers had negotiated long and hard to gain concessions for one of the most ambitious projects of Sultan Abdülhamid II - a railway from Konya to Baghdad.

As it was, the British-Indian interests in the Ottoman vilayets of Baghdad and Basra had expanded steadily after the British shipping interests had acquired the rights of navigation on the Euhprates and Tigris after 1846. By now they controlled more than two-thirds of imports and half of exports of Basra. Eager to gain access to the the Ottoman markets, the German financiers had negotiated long and hard to gain concessions for one of the most ambitious projects of Sultan Abdülhamid II - a railway from Konya to Baghdad.

As soon as the news of the German railway concession were published, The French press had raised worries that the weavers in Lyon would be cut off from their suppliers of Syrian silk, and that the Calais-Marseilles-Suez route to India would be sidelined.

The recent German overtures of protection of Catholic Christian missionaries in the Holy Land was also a centuries-old French prerogative, and the recent announcements of Wilhelm II seemed to threaten it. As a final insult the German plan to open schools along the route openly challenged French cultural activities in the Ottoman realms. All this did not stop the French entrepreneurs in Anatolia from investing, and representatives of Deutsche Bank and the French-majority Banque Impériale Ottomane were eager to seek an accord.

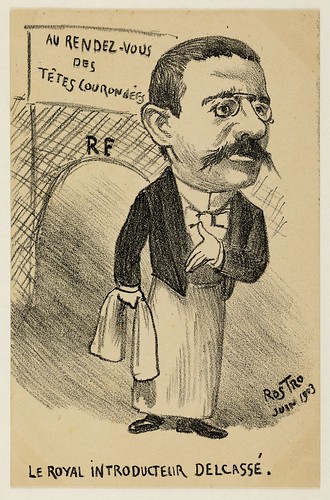

Delcassé, for his part, faced a tough decision. He wanted a deal with Britain, but would have preferred to proceed with his own Moroccan endeavours first. But he was in a minority: most of the French politicians, diplomats and journalists thought Syria a worthy endeavour, and the Middle Eastern approach was strongly lobbied by the Gambon brothers and emerging lobby groups focused around powerful figures like Pichon, Pointcaré, Alexandre Ribot, and Louis Barthou. Furthermore, Delcassé held a deep personal-level attachment to the principle of an equal participation.

Knowing that he could not stop local French financiers from getting involved even if he had preferred to do so, Delcassé took the bull by the horns, and sought an agreement with Berlin at a governmental level. [1] Constans, the French ambassador at Constantinople, prepared a draft memorandum that suggested a deal that would divide the region to respective spheres of interest in order to avoid competition for the emerging Ottoman markets. Armenia, northern Anatolia and Syria would go to the French zone, the coastal region between Alexandretta (Iskenderun) and Beirut would form a neutral zone, and the Germans could focus to Mesopotamia.[2]

Meanwhile Delcassé made sure that the British got wind of these proposals. He was a man of secrets, who utilized the services of Étienne Bazeries and other skilled cryptographers of his personal cabinet noir, a secret espionage and cryptography unit. At the time the French code-breakers at the Quai d'Orsay and the Ministry of the Interior possessed at least partial knowledge of the diplomatic codes and ciphers used by Britain, Germany, Italy, Ottoman Empire, and other countries. Believing that everyone else could be at least as efficient in cryptography, Delcassé was most unwilling to conduct important business through diplomatic dispatches, preferring direct negotiations instead.[3] Having followed the British and German diplomatic traffic in secret for a while now, he had laid down a pre-arranged bait.[4]

Meanwhile Delcassé made sure that the British got wind of these proposals. He was a man of secrets, who utilized the services of Étienne Bazeries and other skilled cryptographers of his personal cabinet noir, a secret espionage and cryptography unit. At the time the French code-breakers at the Quai d'Orsay and the Ministry of the Interior possessed at least partial knowledge of the diplomatic codes and ciphers used by Britain, Germany, Italy, Ottoman Empire, and other countries. Believing that everyone else could be at least as efficient in cryptography, Delcassé was most unwilling to conduct important business through diplomatic dispatches, preferring direct negotiations instead.[3] Having followed the British and German diplomatic traffic in secret for a while now, he had laid down a pre-arranged bait.[4]

And as it was in early February 1903, Clinton Davis of the Morgan Group and Sir Ernest Cassel, two British businessmen were pleased to realize that they had won the support of Foreign Secretary for their endeavour in Mesopotamia - a share in the German railway project. As for the Foreign Office Lansdowne thought “that it would be great misfortune if the railway were to be constructed without British participation.” Lansdowne saw the internationalization of the line as a way to reduce anti-German feelings in Britain: he would have preferred the area to remain without railroads, but felt that they would be built in any case - and because of that it would make sense for Britain to participate.

When French entrepreneurs met the German representatives on 18th of February, they were aware that Quai d'Orsay supported a proposal that would take into account the British request for equal participation. In March, 1902, Lansdowne informally discussed the project with the French and German ambassadors. He explained to Metternich that the British government did not regard the Bagdad Railroad with unfriendly eyes, but but that British participation would necessarily be conditional on British capital and British industry's sharing equally with the other participants.

Both sides had no real options in this regard: as the railway could not be financed without an increase in the custom dues because of the customary Ottoman kilometric financial guarantee, Britain had a practical veto on construction of the line, for the customs could not be altered without a joint agreement of the Powers. In 1903 the modification for the 1881 Murraham degree was agreed upon, and Ottoman state guarantees were released to back finances for the railway construction.

In April 1903 PM Chamberlain, Lord Lansdowne met the Gwinner from Deutsche Bank together with Revelstoke, the representative of City capitalists. The British government guaranteed support for the railway construction. In Paris, Rouvier and Delcassé debated the matter in a Cabinet session. For all his devotion to the Russian alliance, Delcassé was unwilling to see French interests in the Ottoman Empire subordinated to those of Russia. He had asked for equality at the beginning of Franco-German negotiations, insisted upon it before the Chamber, and refused to see it violated in the ministerial debate of 1903.[5]

In April 1903 PM Chamberlain, Lord Lansdowne met the Gwinner from Deutsche Bank together with Revelstoke, the representative of City capitalists. The British government guaranteed support for the railway construction. In Paris, Rouvier and Delcassé debated the matter in a Cabinet session. For all his devotion to the Russian alliance, Delcassé was unwilling to see French interests in the Ottoman Empire subordinated to those of Russia. He had asked for equality at the beginning of Franco-German negotiations, insisted upon it before the Chamber, and refused to see it violated in the ministerial debate of 1903.[5]

Meanwhile in Britain it had become obvious that Ottoman duties were to be raised to cover the costs of the kilometre guarantees of the railway. Gibson Bowles, MP of Kings Lynn, found a useful angle from which to defend his personal investments to the competing Aydin Railway. Why was the government promoting a policy by which the Germans were increasing their trade in Anatolia at the expense of the British? “Hanging on to the skirts of German financiers” would not serve British interests, and it would drive two British-owned railways at the Bosphorus and Smyrna out of business!

Chamberlain asked whether Bowles wanted to cede the Germans and the French a joint control of this shortest route to India? Britain had to get involved to protect her interests in the Persian Gulf, especially in the lands of the sheiks of Kuwait. The railway project was going ahead regardless of what HM's Government did, and left to their own devices, the French would steal the march and strike a bargain with Berlin. The railway would open fresh markets rich in mineral resources for exploitation, but was Bowles willing to cede these profits to Berlin and Paris as well rather than promote the interests of British industry and commerce? On the contrary! Chamberlain stated that the government would negotiate a great deal for Britain, securing equitable access and shipping rates.[6].

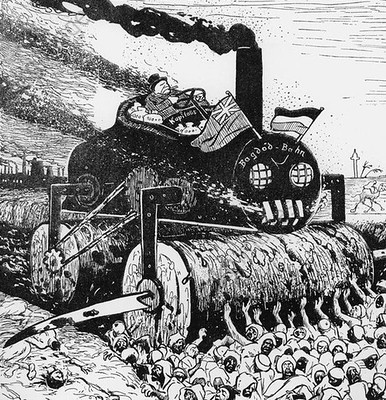

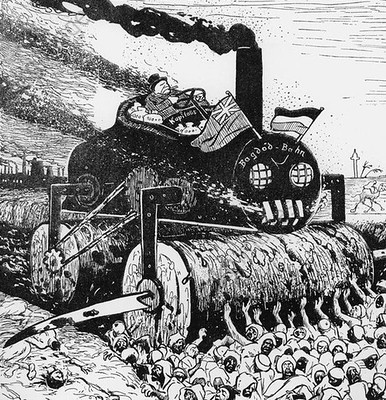

For many British journalists, this was the last straw.

1. In OTL he had no reasons to do so, having already secured the British cooperation by other means.

2. OTL proposal from the second round of the railway negotiations.

3. Delcassé turned down several proposals where he would not be able to directly negotiate - to his contemporaries, this change from the established diplomatic tradition was peculiar, and was often mistaken as pompousness. He showed willingness to ignore Russian complaints when it suited French interests, ie. during the OTL Lorando-Tubini affair.

4. Delcassé has two goals with this project: he wants to get the British involved to limit the German control of the project, and the Germans involved to make French assistance invaluable to Britain and Russia - a classic Yojimbo-gambit.

5. A core idea of his foreign policy was the focus to French international prestige - Delcassé wanted France to be a Great Power that could dictate terms instead of accepting them, refusing all deals where France would serve as a subservient partner.

6. In OTL the slighted Chamberlain led the press war against the plan, despite the fact that the 1903 proposal was exactly the type of imperial project he promoted in general - a chance to get British investments and commerce promoted through new infrastructure projects. Here PM Chamberlain thinks this is a great idea - his idea, in fact - and wholly dedicates himself to promoting it.

As soon as the news of the German railway concession were published, The French press had raised worries that the weavers in Lyon would be cut off from their suppliers of Syrian silk, and that the Calais-Marseilles-Suez route to India would be sidelined.

The recent German overtures of protection of Catholic Christian missionaries in the Holy Land was also a centuries-old French prerogative, and the recent announcements of Wilhelm II seemed to threaten it. As a final insult the German plan to open schools along the route openly challenged French cultural activities in the Ottoman realms. All this did not stop the French entrepreneurs in Anatolia from investing, and representatives of Deutsche Bank and the French-majority Banque Impériale Ottomane were eager to seek an accord.

Delcassé, for his part, faced a tough decision. He wanted a deal with Britain, but would have preferred to proceed with his own Moroccan endeavours first. But he was in a minority: most of the French politicians, diplomats and journalists thought Syria a worthy endeavour, and the Middle Eastern approach was strongly lobbied by the Gambon brothers and emerging lobby groups focused around powerful figures like Pichon, Pointcaré, Alexandre Ribot, and Louis Barthou. Furthermore, Delcassé held a deep personal-level attachment to the principle of an equal participation.

Knowing that he could not stop local French financiers from getting involved even if he had preferred to do so, Delcassé took the bull by the horns, and sought an agreement with Berlin at a governmental level. [1] Constans, the French ambassador at Constantinople, prepared a draft memorandum that suggested a deal that would divide the region to respective spheres of interest in order to avoid competition for the emerging Ottoman markets. Armenia, northern Anatolia and Syria would go to the French zone, the coastal region between Alexandretta (Iskenderun) and Beirut would form a neutral zone, and the Germans could focus to Mesopotamia.[2]

And as it was in early February 1903, Clinton Davis of the Morgan Group and Sir Ernest Cassel, two British businessmen were pleased to realize that they had won the support of Foreign Secretary for their endeavour in Mesopotamia - a share in the German railway project. As for the Foreign Office Lansdowne thought “that it would be great misfortune if the railway were to be constructed without British participation.” Lansdowne saw the internationalization of the line as a way to reduce anti-German feelings in Britain: he would have preferred the area to remain without railroads, but felt that they would be built in any case - and because of that it would make sense for Britain to participate.

When French entrepreneurs met the German representatives on 18th of February, they were aware that Quai d'Orsay supported a proposal that would take into account the British request for equal participation. In March, 1902, Lansdowne informally discussed the project with the French and German ambassadors. He explained to Metternich that the British government did not regard the Bagdad Railroad with unfriendly eyes, but but that British participation would necessarily be conditional on British capital and British industry's sharing equally with the other participants.

Both sides had no real options in this regard: as the railway could not be financed without an increase in the custom dues because of the customary Ottoman kilometric financial guarantee, Britain had a practical veto on construction of the line, for the customs could not be altered without a joint agreement of the Powers. In 1903 the modification for the 1881 Murraham degree was agreed upon, and Ottoman state guarantees were released to back finances for the railway construction.

Meanwhile in Britain it had become obvious that Ottoman duties were to be raised to cover the costs of the kilometre guarantees of the railway. Gibson Bowles, MP of Kings Lynn, found a useful angle from which to defend his personal investments to the competing Aydin Railway. Why was the government promoting a policy by which the Germans were increasing their trade in Anatolia at the expense of the British? “Hanging on to the skirts of German financiers” would not serve British interests, and it would drive two British-owned railways at the Bosphorus and Smyrna out of business!

Chamberlain asked whether Bowles wanted to cede the Germans and the French a joint control of this shortest route to India? Britain had to get involved to protect her interests in the Persian Gulf, especially in the lands of the sheiks of Kuwait. The railway project was going ahead regardless of what HM's Government did, and left to their own devices, the French would steal the march and strike a bargain with Berlin. The railway would open fresh markets rich in mineral resources for exploitation, but was Bowles willing to cede these profits to Berlin and Paris as well rather than promote the interests of British industry and commerce? On the contrary! Chamberlain stated that the government would negotiate a great deal for Britain, securing equitable access and shipping rates.[6].

For many British journalists, this was the last straw.

1. In OTL he had no reasons to do so, having already secured the British cooperation by other means.

2. OTL proposal from the second round of the railway negotiations.

3. Delcassé turned down several proposals where he would not be able to directly negotiate - to his contemporaries, this change from the established diplomatic tradition was peculiar, and was often mistaken as pompousness. He showed willingness to ignore Russian complaints when it suited French interests, ie. during the OTL Lorando-Tubini affair.

4. Delcassé has two goals with this project: he wants to get the British involved to limit the German control of the project, and the Germans involved to make French assistance invaluable to Britain and Russia - a classic Yojimbo-gambit.

5. A core idea of his foreign policy was the focus to French international prestige - Delcassé wanted France to be a Great Power that could dictate terms instead of accepting them, refusing all deals where France would serve as a subservient partner.

6. In OTL the slighted Chamberlain led the press war against the plan, despite the fact that the 1903 proposal was exactly the type of imperial project he promoted in general - a chance to get British investments and commerce promoted through new infrastructure projects. Here PM Chamberlain thinks this is a great idea - his idea, in fact - and wholly dedicates himself to promoting it.

Last edited:

Chapter 174: Britain, Part VIII: Eastern Promises

“No sooner are we clear...of the miserable episode of alliance negotiations and Venezuelan adventures, we are plunged headlong into this Mesopotamian mess, a Baghdad Bungle which is far more serious because it could be more long-lasting, and from which a very determined and vociferous expression of public opinion will be require in order to release us...The withdrawal of the late Premier has left the Cabinet alarmingly deficient of knowledge or instinct in foreign politics and the Kaiser has encountered little, if any, resistance to his projects. Downing Street has become a mere annex of the Wilhelmstrasse and it would make for economy and efficiency if we put up the shutters of our costly Foreign Office!"

The National Review and many other newspapers sought to rally a public outcry against the Baghdad Railway scheme. Many influential British journalists like Leo Maxse, John St Loe Strachey, Sir R. Blenner-Hasset and Garvin did not mince words when they expressed their opposition to any attempts for diplomatic initiatives towards Germany.

They also feuded among themselves whether they really wanted closer relations with either France, Russia or both, but they all viewed Germany with an open hostility. Strachey considered that it was his responsibility as a journalist to “play the watchdog, even if the barking did annoy the neighbours.” Both Strachey and Maxse were convinced that a major European war was inevitable in the near future, and they considered Germany the most likely power to bring it about.

Their newspapers also offered an arena for other Powers to express their views to the British public. A close friend of Maxse, Mr Wesselizki of Associated Press and Novoje Vremja, and Mr Poklewsky at the Russian Embassy worked together with the National Review. For their part, many diplomats at the German foreign office and especially Wilhelm II himself were convinced that “Russians, who of course were interested in thwarting the arrangements which were virtually settled”, were organizing the disrupting effort either from their Paris or London Embassies.

While the press warred against Chamberlain and the flambouyant Prime Minister fired back with full broadsides, the government managed to secure one important truce: Chirol and the Times were neutral - while he was personally lukewarm about the project, he wasn’t actively hostile either. Thus the magazine merely pointed out that Lansdowne was seen as “wobbly”, and that "many prominent figures of our political life" wanted to see Curzon made foreign secretary, for only he and Chamberlain had remained resolute and shown backbone.

As it was, Kuwait the principal source of Arab horses supplied to the British government, while the Sheikh of Kuwait had yet to sign a treaty with Britain - so it remained an open question whether he was under Ottoman or British suzerainty.[1] Nicholas O’Connor, the venerable old attaché at Constantinople was dismayed by the publicity: “Too much influence is exercised by movements of opinion due to causes, which are probably less permanent in their character.”

With great ardour Chamberlain, Lansdowne and Balfour together countered their critics with the argument that sooner or later the railway would be built, whether or not Britain was involved, that railways were an achievement of civilization, and that Britain must not be allowed to isolate herself. Additionally, the railway provided a one-time opportunity to legitimize and anchor British interests in the Gulf, which would be beneficial not only because of the ambitions of the other powers but also because British trade and industry constantly complained about a lack of political support.

Chamberlain never decided anything without an eye on the electorate, but also stuck to his guns when he had made up his mind. He ensured that the majority in favour of the railway plan was able to present the British public with a fait accompli in the beginning of April.[2]

As the press campaign escalated, City representatives were wavering. Senior Baring partner maintained that “any effort on our part to modify the virulence of the press comments would be worse than useless...it would be especially unwise to make any comment to the public press.” Gwinner wanted to publish the text of the convention by which the Ottoman government granted the original concession to the Deutsche Bank, and wanted to send it to The Times. Considering the way the press dealt with the subject, it was perhaps for the best that his British associates talked him out of it.[3]

Another Foreign Office old hand, Esher, felt that the public inquiries to the esteemed world of diplomacy were a nuisance: “There is a lot of money to be made, but a frightened government nearly flinched and ran away...from a press campaign stimulated by stupid fools...The English people, led by a foolish, half-informed press, are children in foreign politics. They have always been so and have paid dearly.”

Lansdowne wrote a private letter where he grumbled how he had been “nearly forced to yield to an insensate outcry...the attempt to discredit such a worthwhile scheme by sharp recrudescence of the anti-German fever...I am afraid that in the long run such attitude will be somewhat difficult to explain.” The fact that he wrote to Curzon shows just how out of touch Lansdowne was regarding the public opinion and British domestic politics. Curzon was slighted.

Already bombarded by letters from his friends to “He had always been opposed to the Baghdad scheme. Although the matter was apparently discussed from its bearing upon Indian interest...no one has ever thought of asking my opinion on the subject.”

During the early months of 1903 Curzon had been urged by his friends in Britain to prepare himself to lead the party, to become Foreign Minister - to save the country from Joe Chamberlain, who had gained a lot of lifelong foes from the way his supporters had attacked Lloyd-George at Birmingham.

Sir Schomberg McDonnell, former Private Secretary of Salisbury, reported in spring 1903 that "Brodrick was hated, Lansdowne stale, Balfour useless and Stanley a standing joke” - Curzon would have no problems of readjustment on his return - indeed he was already spoken of as the next Prime Minister.

At the end of the year he wrote “with the brutality of friendship” that Curzon should not “sacrifice the certainty of being prime minister to the splendid ambition of being India’s greatest viceroy." Every thoughtful man that he had spoken to looked forward to his return and his leadership and would lose heart if Curzon stayed in the East. Writing in deadly earnest, he beseeched the Viceroy to train now for the Prime Minister’s Cup so that, after winning that race, he could run the empire from home.

Esher, a highly adept courtier and intriguer, told him that Curzon “had no superiors in the mighty roll of viceroys.” No one matched him as a statesman; his imagination, capacity for work and gift of expression made him perhaps the greatest of all viceroys. Secretary of State of India, Lord George Hamilton, was astonished by his versatility and vigour, and predicted he would become Prime Minister.

Arthur Godley, the influential Under-Secretary of India, agreed that Curzon was “undeniable a great man...with a touch of genius”, but his sensitivity to criticism and his temperament would prevent him from being a successful party leader. They worried that he had lost interest in home affairs and would be impossible to work with in Parliament because of his “masterful tendencies.”

All of this and the emotional pleas of his American wife, Mary, did little to dissuate him. Convinced that his duty lay in India, Curzon felt that "no power on Earth could persuade him otherwise." Joseph Chamberlain would not have it. The way he saw it was that HM's Government (and He) needed Curzon. Once his official time as a Viceroy was up, Chamberlain opted to send Selborne to the East instead. Curzon had not been tempted to help “a somewhat sick and debilitated party” by returning to take on some undesirable post in the Present Cabinet, but Chamberlain forced his hand.[4]

While the British domestic politics were in turmoil, Lansdowne, Delcassé and Richthofen had managed to hammer out a deal.[5] It left possible extensions to Mediterranean and Persian Gulf ports out, and divided the ownership of the actual railway neatly into three.

Delcassé was pleased - with the railway plan in progress, Britain could not isolate herself from Paris without jeopardizing her interests in the Middle East. He felt that now it was time to press on with with his plans for a wider agreement with Britain, because the anti-German mood in British press had created favourable circumstances for further negotiations.

* German, French and British finances would take part in the construction, management and operation of the railways, each with an equal 25% rate of the stocks.* 15% would go for other partners, and the remaining 10% was the share of the Anatolian Railway Company. * The Board of Directors would have 8 British, 8 French and 8 German representatives, with the remaining six representatives of the 30-man strong board coming from the Ottoman government and the Anatolian Railway Company.

1. In OTL the Times were late to join to the press campaign. In OTL Chirol had expressly encouraged Germany to become involved in the middle east in 1899, repeated this attitude in the Times in 1902, emboldening Chamberlain and his government, and then, in spring 1903, he changed sides, joining with Maxse, Strachey and Saunders in an all-out attack on his own government, accusing them of plans for cooperation with Germany and demanding the very retreat that he then presented as further evidence of the weakness of the government.

2 -3. In OTL the attempt for transparency backfired catastrophically, as the British press ignored the original document and painted a picture of Machiavellian conspiracy. In OTL Chamberlain was in regular contact with Saunders, Maxse and Strachey, and used his connections to turn the agreement given to the Times by Arthur Gwinner, head of the Deutsche Bank and the Anatolian Railway as a ploy to incite the public further by portraying the original treaty as a plot against British interests.

4. In OTL Balfour remarked that letting Curzon return to India had been the worst political mistake in his life.

5. In OTL the first proposal, seen in the side text summary, fell because the British government balked from the negative publicity, because Chamberlain was already firmly anti-German and campaigned against it, and because the government was already criticized because of the Venezuelan intervention. TTL Chamberlain is the PM, Venezuela went more smoothly than OTL. In essence the British government had already spent their political capital to suffer further criticism because of cooperation with Germany in OTL, whereas in TTL it not Venezuela, but the Baghdad Railway that marks the point where the opposition grows too strong to risk any further moves.

Last edited:

Chapter 175: Britain, Part IX: "I would like to have a civil conversation about your statement..."

The greatest influence on policy-making outside the Foreign Office was Arthur Balfour, who had under the earlier ministry deputized for Salisbury as foreign secretary on several occasions. Lansdowne referred to him a great deal on larger issues of policy, for he had the capacity for detachment and logical thinking which made his memoranda invaluable.

Balfour was renowned for his social charm, coaxing the best out of people and persuading them to do what they’d have rather not done. His influence was especially important in foreign policy and defence - matters which, in his view, were far too important to be left to wrong hands.

He got his chance to shine in December 1902, when the Committee of Imperial Defence was set up on a new basis as Sir George Clarke (Lord Sydenham) as the first secretary.

By early 1903 the fiscal situation looked so precarious that the Exchequer warned the cabinet about “possible public commotion.” Funding was the key topic in the C.I.D. How to pay for the strategic imperial aspirations, and how to divide the money between the services?

As it was, the Committee was divided into two competing camps. The representatives of the Army were eager to utilize the public fear of an invasion. Fearful of potential reforms and budget cuts after the Boer War, their lobby in press and parliament talked about the old nightmare of a continental anti-British "Napoleonic bloc."

The naval experts in the Committee advocated calm and reassurance. To them, the highly popular invasion literature of previous decades was about as credible as the War of the Worlds.

Admiral Battenberg, director of naval intelligence, made structured reports and insisted that an invasion remained entirely impossible while the British fleet remained undefeated. Expert of the sea power of the members of the Triple Alliance and well informed about all continental navies, he was a credible figure because - not despite of - his Austrian origins.

According to his view the best the enemy could do, in a case where the political, military and meteorological conditions were absolutely right, would be a small raid carried out by a maximum of 5 000 men - an act entirely incommensurate with the associated risks. All potential targets (Plymouth, Portsmouth and Sheerness-Chatham) were all defended by numerous Royal Navy units. "Even poorly trained riflemen would likely prove an insurmountable barrier for the enemy" that attempted something so foolish, Battenberg remarked.

On the other side of the table the Army representatives refused to be drawn into any discussion of naval matters, and consistently acted as if crossing the Channel to Britain and landing on the British coast would one of the easiest operations a continental army could undertake, seeing Channel only as a distance to be negotiated. They ignored Admiralty arguments, presenting time and time again views that only aggressor would benefit from technological developments, such as steam power.

Admiral Battenberg replied by mentioning such changes as rapid-firing artillery, wireless and telegraph, torpedo boats and submarines, day and night operations, ocean-going torpedo-boat destroyers, new submarines and light cruisers. He demonstrated that enemy battleships would have to protect the invasion convoy from repeated submarine and torpedo boat attacks. The Royal Navy would then be in a position to launch a counteroffensive, using its own battleships, which by then would have arrived on the scene.

Not to be dismayed in the face of facts and logic, the Army proponents created their own parliamentary commission. Consisting almost entirely of elderly members of the House of Lords, including a good number of long-retired army officers and active officers in the volunteer forces, they had a clear goal. Liberal Imperialist Henry S. Wilkinson, a self-proclaimed military expert, journalist and volunteer forces advocate ensured the work of the commission - “the great spectre of a great invasion" received the desired publicity.

No naval officers of note sat on the commission - which was not surprising, since the main intention from the outset was to maintain the division of tasks between army and navy, and to exact further resources for the Army. Between May and November 1903, the commission met 82 times, and heard from 96 witnesses - only one of them a naval officer, a long-since retired Admiral Sir John O. Hopkins, who alone was willing to publicly declare to the press that an invasion of Britain was possible.

Balfour, assigned by Chamberlain to the committee, was always fully prepared, never missed a meeting, and kept the discussion to the facts.[1]

After he felt that he had heard both sides Balfour made a memorandum where France was marked as the greatest potential threat. Having called her “the most obvious danger to European peace...an incalculable quantity” in 1899, Balfour was largely repeating his previous views. He did not do so because the threat posed by Germany did not matter or because Balfour opposed detenté with Paris, but because expert opinion was unanimous.

France, located so much closer to Britain than Germany, was more likely to be able to conduct a successful operation against the British Isles, and had repeatedly boasted of that ability in actual military maneuvers. The fleet strength assessment in 1903 was clear. The United States and Germany were catching up in terms of battleships and battlecruisers, but when new technology was included, France had the greatest capabilities to threaten Britain, in a case where they

German prospect to threaten Britain were even more hopeless. In order to mount a surprise invasion, they would have to:

- somehow manage to keep a whole operation of a 70 000 men-strong invasion secret, both in planning and performance

- managed to completely destroy all Royal Navy units in British waters in a simultaneous surprise attack to all British naval bases

- mustered a transport fleet of the order of 210 000 gross register tons, greater than the tonnage of all available craft in all of the Channel ports, including the merchant fleets

- Would have a time window of embarkation for at least six days, bringing all other maritime traffic to a halt

- Managed to somehow cross the Channel while keeping the convoy hidden, coordinated and effectively defended for the 20 hours the crossing would take with slower merchant ships

- Assuming that everything above went as expected, including meteorological implications, landing and securing the coastline would take some 48 hours

The naval experts were unanimous in their view: such invasions would fall prey to Royal Navy: “Every shot they fired, every torpedo they discharged, would find a victim among the thickly crowded shipping. Submarines by day, torpedo boats by night and cruisers at any time." As long as Britain ruled the waves, even the control of Channel Ports would not avail hostile French intentions. And if France could be kept at bay, no other country would present a threat to Britain, Balfour rationalized to Chamberlain. What was clear from the committee meetings was the fact that the British security depended on the strength of the Royal Navy.

- Either embark sail the invasion fleet to the sea during the night (giving a time window of only six hours), or shut down the whole telegraphic system and their land borders beforehand

- Gather 25 000 men to the available seaports beforehand, and then using 80 trains, c. 600 men per train, to bring the remainder of the expedition to its point of embarkation

- Hamburg, the only city on the German coast that could possibly harbour such numbers in secrecy was full of British shipping, merchants and trade agents and other sympathetic foreigners, so it would be inconceivable that secrecy under such conditions could be achieved

- Since Hamburg also lies on a tidal river, some 65 miles from the sea, the passage of a fleet of transports from the docks would be reported before the first ship could leave the docks, thus giving at least 24 hours to organize a naval force to meet the invaders.

- Emden, Wilhemshaven, Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven and Brunsbuttel lacked capacity to accommodate and dispatch such an expedition. Emden also had a resident British Vice-Concul and a foreign staff in the telegraph company office.

- It would be barely possible to get a maximum of ten thousand men embarked from Emden in secret - provided that the needed shipping would already be set in place without exciting widespread comment. As the troops would also have to be brought in by train, secrecy would again be impossible to achieve.

- Troops going to Wilhemshaven would pass through Oldenburg and probably Bremen as well - both places had numerous Englishmen of note working in commerce), and they would certainly take note of a massive train transport of troops. Thus the maximum number that could pass the lock gates during high water would be from 10 to 15 thousand.

- Bremerhaven also had always numerous British subjects and ships in port, and the lock gates worked around high water, once again making surprise night-impossible.

- At Cuxhaven the troops woulds have to pass through Bremen or Hamburg, once again ruining the chances for necessary secrecy.

- If no one from the pro-Danish population would raise alarm, Brunsbuttel would offer a chance for more secret embarkment - but gathering the shipping would once again be a clear signal that something was amiss, once again giving the Royal Navy ample time to mobilize the fleet.

Joseph Chamberlain addressed the anxious public in a speech at the United Service Club.

“My own view is precisely and exactly the opposite of that which was expressed by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman! (Cheers) I do not believe myself that home defence requires a large regular army (Hear, Hear) … I believe the public at large have inverted the true importance of the problem with which this Empire has to deal. Our great difficulty is not home defence, the Navy can deal with it formidably well (Cheers) ...it is a foreign difficulty!"

Chamberlain, following the advice of Balfour, finally assigned the Under-Secretary of State at the Admiralty as the new Secretary of State for War. The man in question, Sir Hugh Arnold-Forster, perceptibly altered the balance in favour of the naval experts, but since he knew the problems of War Office and was highly regarded in the Army circles, he was able to bring consensus and cooperation between the two service departments.

The cost of placating the Army lobby was an acceptance of an a standing force of at least 70 000 men, ensuring retention and financial support for a reduced volunteer force. Meanwhile Lord Selborne from the Admiralty was “in despair about the financial outlook, because these cursed Russians are laying down one ship after another.”The Treasury even toyed with the idea of adding an additional £1.75 million separate naval budget just to buy two Chilean battleships away from a possible Russian purchase.[2]

Chamberlain made the results of the CID discussions about defence policy public. Their final document, the Balfour Memorandum, was a milestone in British defence policy. Balfour had digested all the information available, and the conclusion was clear: for the time being France and Russia remained most dangerous enemies among the Great Powers. And as long Russian expansion presented a challenge, then France, through her Russian alliance commitments, was also a threat that would have to be taken into account.

1: in OTL he has there as a Prime Minister, TTL Joe Chamberlain delegates him to the job, recognizing his talents for the task ahead.

2: In OTL Selborne had such a view when the committee started its work. TTL Britain does not buy the Chilean ships since the tensions between Japan and Russia are not as high as in OTL.

Driftless

Donor

After Fachoda, the French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé was infuriated about the fact that France lacked strength to evict the British from the Nile valley. He had to swallow his pride and accept the Anglo-Egyptian condominium in Sudan as well, and in return he secured British acceptance to the French imperial expansion to North-Western Africa. Fachoda was as great a humiliation to the French as any in the history of the Third Republic, and the fact that it took place in the middle of the Dreyfus Affair just fanned the flames of xenophobia in general. For Delcassé himself, it was a personal insult.

^^^ I just finished the book "The Mamur Zapt and the Return of the Carpet". It's a mystery/thriller set in 1908 Cairo. The Mamur Zapt is a title for the British run political police - a sort of MI-5 for the "unofficial", but very substantial British control of Egypt in that era. The tale outlines the very byzantine machinations of political and cultural life of Egypt, between the British, Egyptian leadership working with the British, the anti-British Egyptian Nationalists, the French, and various factions of the Ottoman's. Everyone is working at cross-purposes to each other - consciously trying to disrupt their plans, it's very chaotic. The British hold the strong hand though.

Last edited:

The reported quotes and views of Balfour are 100% OTL!Hmm so Britain is both anti-France and anti-Germany; their best play with OTL hindsight is to let the Continent bleed and finance the whole mess, which preserves their men and materiel and bleeds dry their putative rivals in Europe

First summary is from Draft Report on the Possibility of Serious Invasion, Committee of Imperial Defence 1903.

The second part about Germany is from later OTL correspondence between British naval attache to Germany and the Foreign Office from 1912.

Also: the rivalry between Britain and Germany is not going away. The British did exactly this summary historically, and drew the conclusion that it would make more sense to deal with the worse threats diplomatically than through military expenditure. Then they got partially carried away by further developments and changed their own strategies accordingly.

Last edited:

Neither Joe Chamberlain or Mr. Herzl and his associates did not really comprehend the complexity of the situation there in OTL - and in TTL.^^^ I just finished the book "The Mamur Zapt and the Return of the Carpet". It's a mystery/thriller set in 1908 Cairo. The Mamur Zapt is a title for the British run political police - a sort of MI-5 for the "unofficial", but very substantial British control of Egypt in that era. The tale outlines the very byzantine machinations of political and cultural life of Egypt, between the British, Egyptian leadership working with the British, the anti-British Egyptian Nationalists, the French, and various factions of the Ottoman's. Everyone is working at cross-purposes to each other - consciously trying to disrupt their plans, it's very chaotic. The British hold the strong hand though.

I have to say that I'm going to disagree with m'learned colleagues upthread and say that a Central Powers victory in WW1 is the well worn cliché of the period, and a German/British alliance generally the usual route taken to get there. This would not be the first plot twist in the timeline that has been done before, but it's the first I've seen done many times before.

In purely quantitative terms, doubtless you are correct: but in terms of the well-crafted, profoundly researched and thoughtful timelines, I feel it tends to be the opposite. It is much harder to write a credible CP victory timeline, and it is those timelines I was referring to. But I share your confidence in the TL and its author

Moreover, after the last raft of (excellent) updates, I have become 100% convinced that an Anglo-German alliance is off the cards ITTL. Yes, Britain has identified France as its most dangerous rival - as it did IOTL, which is precisely why they chose to neutralise them diplomatically as opposed to militarily. The Francophilia of particular Cabinet members and Edward Grey's unsanctioned action, plus the German catastrophic handle of the July Crisis, did the rest. ITTL, the latter part has likely been butterflied away as concerning the British, and while the Germans haven't suddenly grown a brain, they do look a lot more open to a settlement than they were IOTL. What hope there was of a true Anglo-German alignment was dashed when Billy opened his mouth, but the fallout seems not as bad as IOTL. So in essence my prediction is that Britain will remain equidistant between Germany and France, liking them a bit more and a bit less than OTL respectively, and therefore choose neutrality in the Great War.

If my prediction is true, there will be some very important ripple effects. Britain will likely remain the center of world finance. But for all the hurt they will suffer, the belligerents (those that survive the war anyway) will have gained some important advantages/blessings in disguise: a test of just how much the modern state can accomplish and therefore how limited orthodox economics is. Industrial mobilisation on an unprecedented scale. A much more powerful women's movement (particularly for Germany and France). And perhaps most of all, the crucial R&D and government/industrial connection that proved so fundamental to the long-term success of the United States IOTL. The latter will probably be another player severely impacted by neutrality. No GW for them means no Bell Labs down the line, with all the attendant consequences. Don't be surprised if computers and big tech companies are primarily a French and German concern ITTL. Less federal centralization of power will also mean the US will have even more internal diversity than it did IOTL, with some places looking bizarrely underdeveloped while others look very "European". So Britain will look like the winner in the short term, but is likely to lose out on some critical lessons and developments of modernity. And god knows managing the Empire and Ireland won't be fun regardless.

Chapter 176: Anglo-French relations, Part 1: A mutual temper of apathetic tolerance

A clever young provincial lawyer had gone far. From law to journalism, and from the lobby of the Chambre des Députés to office in 1889 after marrying a wealthy widow had secured him the funding to do so. Five years later he had become Minister, first for Colonies and then to Quai d'Orsay. From the day he secured this post, he pursued a policy that had a single aim: to strengthen the position of France. His policy was rooted in the pursuit of French interests as he saw them: everything else was just means to an end.

His first ministerial posts in the 1890s were as Under-Secretary, and later Minister, for the Colonies, where he supported a policy of expansion which led to local colonial conflicts with Britain, and this earned him a public reputation as a diplomat who "would stand up to John Bull." But when push came to shove at Fashoda, Mr. Delcassé convinced the Cabinet that standing up to John Bull in this particular instance offered no advantages to French interests.

Delcassé had the capacity to think and plan far ahead. After Fashoda the Parisian press was so anti-British that any kind of deal with Britain was night-impossible. But perhaps easing colonial frictions would at least avert the danger of war with England? When Delcassé sent Paul Cambon to London, he instructed the new Ambassador to spare no efforts to seek a settlement of existing points at issue between France and England. Cambon dined with Queen Victoria, and met with Lord Salisbury through the winter and spring of 1899. After they struck a deal, when the delimitation of the frontier between French Equatorial Africa and the Sudan was agreed in March 1899.

Cambon happily suggested that such mutually friendly spirit might help London and Paris to solve other Anglo-French colonial disputes in places like Madagascar, Newfoundland, Muscat and Shanghai. Salisbury merely smiled. "I have the greatest confidence in M. Delcassé and also in your present government. But in a few months they will probably be overturned and their successors will make a point of doing exactly the contrary to what they have done. No, we must wait a bit."

Personally Lord Salisbury summarized his true views to Lansdowne. Due the prevailing circumstances Anglo-French relations could never rise higher than "a mutual temper of apathetic tolerance...anything like a hearty good will between the two nations will not be possible." Cambon was persistent, but by summer of 1899 further talks had failed to make any progress on these problems. By August Delcassé spoke 'in a studiously impressive manner, of the impossibility of keeping relations with England on a friendly footing'.

By autumn 1899, Delcassé had abandoned all hope of an understanding with England for the foreseeable future. He believed, however, that England's involvement in the Boer War had offered him an alternative to the solution of the two questions of Egypt and Morocco. Instead of settling these questions jointly and by agreement with England, he contemplated the idea of solving them separately and without agreement with England: by establishing French rule in Morocco whilst at the same time ending English rule in Egypt. After all, it seemed very clear was clear that the British would only value friendship with countries which commanded respect and safeguarded their own interests. So he put his diplomats at work, seeking for potential allies.

Chapter 177: Anglo-French relations, Part 2: Friend or Foe?

As soon as the Boer War distracted Britain, Delcassé went to work. He offered Italy support for her ambitions in Tripolitania if she in turn would agree to French ambitions in Morocco, bypassing the opposition of the French Ambassador in Rome and the old hands of the Quai d'Orsay. Delcassé already intended to follow agreement with Italy by a Franco-Spanish partition of Morocco in which the lion's share would go to France. He also intended to strike a bargain with Germany: "As for Germany, which cannot assert political rights in Morocco, it seems that an understanding can be established with it, if we show ourselves prepared not to hamper it in other parts of Africa than she can aim and which are not indifferent to us."[1]

For the British, whom he rightly regarded as the principal opponents of future French rule in Morocco, he was willing to offer only guarantees of the neutrality of Tangiers and of her freedom of commerce in a French Morocco. Delcassé had no illusions that these minor concessions would do much to soften England's opposition, but he believed that because of the Boer War he would in the end persuade London to accept a new Mediterranean status quo where the three Latin powers had all advantaged their colonial expansions.

He also put forward a plan for Egypt, contemplating a possible intervention in the Boer War with the support of the French Russian ally - and Germany. Seeking to find a common cause with both in the early autumn of 1899, Delcassé discussed with the Russian ambassador the possibility of a new initiative on Egypt. These plans were ambitious - and alarming - enough to summon the Russian Foreign Minister Count Muraviev to Paris. Happy to promote more cordial relations between the new key ally and Germany, Muraviev agreed to send feelers towards Germany about the prospect of intervening to the Boer War with the Dual Alliance. Muraviev was initially optimistic, but overture proved unsuccessful, much to the dismay of Delcassé.

Early in February 1900 a mutiny of Egyptian troops got Delcassé extremely exited. Lord Cromer and Sir Rennell Rodd, the British Proconsul and his second-in-command, were facing a serious crisis, just when Britain was desperately scrambling troops from all over her Empire to meet the new flashpoint in China. This was the chance! The French minister in Egypt, Georges Cogordan, kept battering Paris with pleas for urgent action. Germany remained aloof, but Muraviev and especially Delcassé were like cats on hot bricks.

A veteran French agent, Jules Hansen, was instructed to seek a meeting with the German Chancellor Hohenlohe in order to clarify the situation, while Delcassé and made a further approach to Germany through the columns of the Matin, his de-facto mouthpiece in diplomatic circles. In a leading article the Matin he openly called Germany to join with the Dual Alliance in a joint intervention to end the English occupation of Egypt. However, Germany's only response to the question of a new initiative on Egypt was evasive. In late February Delcassé showed that he was willing to play hardball.

On the same day Germany was formally invited to join with the Dual Alliance in offering to mediate in the Boer War, Delcassé represented the rest of the French government a memorandum, "Classer au dossier reserve intervention russo-française au sujet du Transvaal", regarding military preparations to threaten British colonial holdings and to intervene to the Boer War. A month earlier he had estimated that Britain would most likely accede to a unanimous call by the continental powers for the evacuation of Egypt, but that "it would be wise to prepare for overcoming potential resistance as well."

Rattling sabers in Mediterranean while the Boxer War escalated and the Boer War raged on, Delcassé was optimistic that Germany could not resist the temptation to join forces with France and Russia. On 15 March 1900 Montebello, the French ambassador in Russia, reported that Wilhelm II had set a precondition to any negotiations and meditation attempts that the Powers in question should first undertake to guarantee the status quo in their "European possessions." Voluntary public renunciation of all claim to the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, lost to Germany by the treaty of Frankfurt in 1871, was still an anathema to the French public opinion. Any French government would inevitably be swept out of office in a day.

Ambassador Montebello, demoralized, became convinced that establishing an agreement with Germany for any political action, France would have to renounce in advance any claims to A-L. Delcassé, after private apolectic correspondence from future chancellor Eulenburg relayed via the First Secretary of Berlin Embassy, Raymond Lecomte, felt that the best they could hope from now on were agreements limited to special matters. From this point on, however, Delcassé flat-out refused to negotiate with Berlin "...unless he had the guarantee that he would not be asked, above all, to consecrate the conquest of 1871, because he would not consent at any price to sign the Treaty of Frankfurt a second time!"[1]

1: Rest of this update is all OTL. This was also the OTL standard reply of Delcassé to all attempts to negotiate with Germany after 1900. This earlier private correspondence from Eulenburg and his ascendancy to chancellorship makes Delcassé willing to use Germany as a pawn in his gambits - he is still mortally afraid of German plans for the future of Europe, and determined to foil them. But unlike in OTL Wilhelm II, Bülow and Holstein were happy to send Delcassé packing empty-handed, convinced that Britain would soon come to the table in any case. Here francophile Eulenburg makes Delcassé bit less uncompromising towards Berlin, mainly because he is forced to deal with a different geopolitical situation than in OTL.

Last edited:

Chapter 178: Anglo-French relations, Part 3: English Opening

Their initial plans foiled, Delcassé and Cambon nervously waited for the future. Already in October 1899, on the eve of the Boer War, Cambon reported to Paris: "Everything is difficult for us here. The rage of imperialism turns all heads and I am not without disquiet about the future." In 1900, when Lord Salisbury retired from the Foreign Office and was succeeded by Lansdowne as Foreign Secretary in October 1900, Delcassé was once again initially optimistic the chances for rapprochement had improved.

His new colleague was a statesman of wide experience: Governor-General of Canada, Viceroy of India, and most importantly Secretary for War from 1895 to 1900, when he took much of the blame for the state of the Army at the beginning of the Boer War. He thus had first-hand knowledge of the problems of modern war and imperial defence, and was thus an unlikely figure to do anything too rash. A greatgrandson to Talleyrand was also fluent speaker of French - a feature Ambassador Cambon especially liked, since he had refused to learn a word of English himself.

But this was all pointless as long as one also took into account Joseph Chamberlain, who though not yet Prime Minister already came near to being the effective leader of the government. For Delcassé the new British Prime Minister had all the appearance of a determined Francophobe. Even Salisbury had said in 1898 that "he could never decide whether war with France... is part of Chamberlain's object or not." The future prospects of Anglo-French relations seemed bleak indeed. With the beginning of the Boer War in October 1899 the mutual hostility of public opinion on both sides of the Channel became even greater than during the Fashoda crisis a year before. Once again there were rumours in France that Joseph Chamberlain intended to make war with the French as soon as Britain had beaten the Boers.

These rumours were fed to the French statesmen from Sir Charles Dilke, whom they could reasonably consider a reliable source, for he was regarded as a close friend of Chamberlain, enjoying quite of a reputation as an expert in foreign affairs. The fact that this was most likely calculated bluff and false information fed from the equally nervous British leadership that was extremely worried about a continental coalition was entirely missed.[1] In the later months of 1899, as in the aftermath of the Fashoda crisis a year earlier, Delcassé felt desperate enough to orchestrate an act of bravado with public claims that he felt confident of German as well as Russian support against English aggression. In reality the French leaders dreaded that the Royal Navy leadership might try to "copenhagen" the growing French fleet before it could be expanded enough to become a serious challenger. [2]

When the French attempt to rally together an anti-British continental bloc had failed and Chamberlain sought an alliance with Germany, the French could do nothing but wait. In the spring of 1901, when the latest round Anglo-German alliance negotiations had ended without a clear conclusion, Delcassé and Cambon saw an opportunity. They knew the British were already negotiating a military alliance with Japan, but had no formal alliance commitments in Europe. The French ambassador once again repeated the offer that potential sources of colonial discord should be mutually examined and, if possible, eliminated. Lansdowne, eager to find out what was in offer, immediately passed this suggestion to Chamberlain, whose department would be affected by any talk involving colonies. The final British reply was elusive. And then Lord Salisbury stepped down as Prime Minister and was replaced by Joseph Chamberlain, who, as Eckardstein wrote to Eulenburg, "exercises relentlessly the dominant influence in British policy." Chamberlain soon declared publicly that the British people must count upon themselves alone: "I say alone, yes, in splendid isolation, surrounded by our kinsfolk..." - and then went ahead to sign the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

Delcassé replied by the Baghdad Railway scheme, and made sure that the anti-German sentiment in British press did not lack funding. The next move from Chamberlain arrived by late autumn. The Prime Minister requested Lord Cromer to transmit, through the French Chargé d'Affaires in Cairo, his hope for discussing colonial matters with France.[3]

1. OTL - the rumours were real, but whether they were relayed to the French on purpose is an open question.

2. OTL - the idea was not limited to the German fleet.

3. In OTL Chamberlain, still a Colonial Secretary, said in October 1902 to Cromer that: "Delcassé... seems to me to have done much to make possible an Entente Cordiale with France which is what I should now like. I wonder whether Lansdowne has ever considered the possibility of the King asking the President to England this year."

Last edited:

Chapter 179: Anglo-French relations, part 4: Studien über Hysterie

Delcassé felt that the world was changing, and France had to make great efforts to keep up with the twists and turns of European Realpolitik. At the beginning of the century he had guided France out of the exile to the diplomatic wilderness imposed by Bismarck.

Right now, he was looking southwards. Seeing Pan-German expansionism behind every initiative of the German government, he worried about the future of the Hapsburg realms along the Danube. Delcassé felt that the German Naval Laws were not aimed against Britain. No, they had much more sinister goal: the anti-British attitude was just a ruse, and the fleet was secretly prepared for Trieste, the main port of the Dual Monarchy. A discipline of Charles Benoist from the Ecole des Sciences Politique, he was certain that Germany was looking for a southern port, and wanted to divide Austria-Hungary with Russia after the death of Emperor Franz Joseph![1]

Count Muraviev was polite when Delcassé, alarmed, arrived to St. Petersburg to tell him about his fears in 1899. The Dreyfus affair and the bitter conflict between French Church and State had transformed Russia's traditional distrust of France's republican government into thinly disguised disgust. But while Russian diplomats the world over treated their French colleagues with disdain, Russian confidence in Delcassé himself increased steadily. Muraviev considered the Frenchman as his personal friend, and did his best to calm down his paranoia. Russia agreed to strengthen the alliance with Paris in 1899 mostly because the ruling triumvirate of Witte, Kuropatkin and Muraviev were alarmed by news that considerable section of the French press were in favour of a rapprochement with Germany.

Delcassé was actually not totally opposed to the idea, as his Egypt schemes had showed. He privately toyed with the idea that France could give her consent to German expansion to former Austrian territories, provided that Germany would in return be willing to return Alsace-Lorraine to France. "Is it unreasonable to think that in such circumstances Germany ... would not consider the revision of the Treaty of Frankfurt too high a price to pay ? History has seen stranger things." Later, in spring 1901, he told to the new Vice-President of the CSG, the French Supreme War Council General Brugere: "We are fully prepared for the events which will follow the death of Francis Joseph. Germany wishes to take Trieste and she will have against her almost the whole of Europe."[2]

Fear of Germany as a Mediterranean power and central-European superpower that would annex the Austrian half of the old Hapsburg realms was not the only thing that made Mr. Delcassé feel ill at ease. Colonial expansion to Morocco, a plan set in motion during the Boer War, would ultimately require British support or at least tacit acceptance. Morocco was right next to Gibraltar. British traders had commercial interests there. And the Moroccan Army was led by bagpipe-playing Caid Maclean, a Scotsman who had little love for the idea of French encroachment from her Algerian territories. The Pan-Germans were talking about Morocco, and had established a Moroccan Company to expand German influence in the country. There also other Powers to be taken int account. Delcassé had been eager to end the Spanish-American War just to keep the US from having any ideas about seizing Spanish Moroccan enclaves, and the idea of Open Door to Moroccan trade disturbed him.

And now the Germans were set out to build a large, modern fleet. This forced France to either meet this expansion or accept the fact that in a case of war the German sea-power might cut France off from her colonies and blockade her ports. Naval expansion to meet this threat would be expensive. When compared to that, trying to gain support or at least benevolent neutrality of the strongest navy on the face of the Earth was worth a try. With future naval security and colonial expansion in mind, Delcassé begun to warm up to the idea of a some sort of an agreement with Britain.

1. All OTL - Delcassé urged Russia to re-activate her policies in the Balkans to be ready to prevent sudden German moves towards Austria. The OTL argument Benoist used and that Delcassé accepted was that "the North Sea leads nowhere, whereas the Mediterranean leads everywhere, being at the centre of the commercial world. Through this outlet to the south, Germany would become a central and universal power."

2. All OTL.

Last edited:

Chapter 179: Anglo-French relations, part 5: By Jingo!

After the tensions between Russia and Japan were settled by the Yamagata-Muraviev Agreement of September 1901 and Chamberlain and Lansdowne had to accept that their attempts for an agreement with German were leading nowhere, Delcassé shrewdly placed France to the same table with London and Berlin at the Baghdad Railway project.

After proving both sides that France was a power they could do business with, he hoped that he could gradually sway London to a colonial bargain.

Early in 1901 the French made some inquiries about the British attitude to Morocco, but Delcassé did not believe that he could get the sort of free hand there that he wanted France to have. Cambon also raised again the centuries-old question of French fishing rights off Newfoundland. Neither approach made much progress. Lansdowne returned to these early feelers with an offer regarding Siam. He followed the established method of Salibury: when a colonial agreement was made with a Great Power, it had to have as little negative impact on British relationship with any third power, above all in the form of repercussion in Europe itself. He refused to be drawn into horse-trading proposed by the French: not opposed to colonial exchange in principle, he preferred to talk about Siam, West Africa, the New Hebrides, or Newfoundland. But Morocco was different, since long standing German interests there had been expressly acknowledged by Lansdowne in the tradition of British politics where Germany was encouraged to direct her colonial ambitions to areas where collisions with Britain would be less likely.

If the various impulses towards a Franco-British agreement were to come to anything, governments on both sides of the Channel had to be able address the public opinion. The press was vigilant and leaks were not unknown, especially since the diplomatic corps on either country were divided on the issue. Moreover, any far-reaching agreement would have to be ratified by the parliaments of the respective countries, allowing pressure groups to have an impact to the public opinion and through that to the politicians themselves. Fashoda and the Boer War had left the journalist circles mutually hostile.

In Britain the influential press barons like Maxse and Strachey knew that the music hall crowds eagerly adopted a truculent attitude towards France and Germany alike. Jingoism was profitable, but as criticism towards Germany grew in the yellow press, hostility towards France was becoming less harsh than it had used to be a few years earlier. The Times, the Spectator and the National Review were all openly discussing the idea of an alignment with France as a possible lesson directed against Germany. Radical liberal press read the situation very differently - an agreement with Paris would and should not be anti-German in spirit, and could mean a possible end to the traditional Anglo-French enmity and maybe a beginning of a new era of a global Great Power concert embracing democratic states.

The Manchester Guardian and the Speaker published articles questioning whether an Anglo-French agreement would be worth the complications for the broader power arrangements that would surely follow. Detenté could on no account be allowed to stand in the way of other alliances, even with Germany, and should serve instead as the starting point for a whole network of treaties. Gladstonian idea of the old Concert of Powers was alive and well, contesting the ideas of secretive balance of power deals or open power blocks that would leave core members of the state's system cornered and encircled.

As the press moved the British public debate ahead while Lansdowne, Delcassé and Camille Barrère quietly started to map the potential roads ahead, it became apparent that neither side was entering to the negotiations with closed ranks and a joint sense of purpose. Different groups had different aims, and they sought to make themselves heard and their grievances addressed in all major topics that the negotiations would have to deal with in order to succeed.

After proving both sides that France was a power they could do business with, he hoped that he could gradually sway London to a colonial bargain.

Early in 1901 the French made some inquiries about the British attitude to Morocco, but Delcassé did not believe that he could get the sort of free hand there that he wanted France to have. Cambon also raised again the centuries-old question of French fishing rights off Newfoundland. Neither approach made much progress. Lansdowne returned to these early feelers with an offer regarding Siam. He followed the established method of Salibury: when a colonial agreement was made with a Great Power, it had to have as little negative impact on British relationship with any third power, above all in the form of repercussion in Europe itself. He refused to be drawn into horse-trading proposed by the French: not opposed to colonial exchange in principle, he preferred to talk about Siam, West Africa, the New Hebrides, or Newfoundland. But Morocco was different, since long standing German interests there had been expressly acknowledged by Lansdowne in the tradition of British politics where Germany was encouraged to direct her colonial ambitions to areas where collisions with Britain would be less likely.

If the various impulses towards a Franco-British agreement were to come to anything, governments on both sides of the Channel had to be able address the public opinion. The press was vigilant and leaks were not unknown, especially since the diplomatic corps on either country were divided on the issue. Moreover, any far-reaching agreement would have to be ratified by the parliaments of the respective countries, allowing pressure groups to have an impact to the public opinion and through that to the politicians themselves. Fashoda and the Boer War had left the journalist circles mutually hostile.

In Britain the influential press barons like Maxse and Strachey knew that the music hall crowds eagerly adopted a truculent attitude towards France and Germany alike. Jingoism was profitable, but as criticism towards Germany grew in the yellow press, hostility towards France was becoming less harsh than it had used to be a few years earlier. The Times, the Spectator and the National Review were all openly discussing the idea of an alignment with France as a possible lesson directed against Germany. Radical liberal press read the situation very differently - an agreement with Paris would and should not be anti-German in spirit, and could mean a possible end to the traditional Anglo-French enmity and maybe a beginning of a new era of a global Great Power concert embracing democratic states.

The Manchester Guardian and the Speaker published articles questioning whether an Anglo-French agreement would be worth the complications for the broader power arrangements that would surely follow. Detenté could on no account be allowed to stand in the way of other alliances, even with Germany, and should serve instead as the starting point for a whole network of treaties. Gladstonian idea of the old Concert of Powers was alive and well, contesting the ideas of secretive balance of power deals or open power blocks that would leave core members of the state's system cornered and encircled.

As the press moved the British public debate ahead while Lansdowne, Delcassé and Camille Barrère quietly started to map the potential roads ahead, it became apparent that neither side was entering to the negotiations with closed ranks and a joint sense of purpose. Different groups had different aims, and they sought to make themselves heard and their grievances addressed in all major topics that the negotiations would have to deal with in order to succeed.

Last edited:

less of Russian action was also growing as tensions within the Ottoman Empire kept growing.

This post and many others are walls of black on dark mode

In 1900, when Lord Salisbury retired from the Foreign Office and was succeeded by Salisbury as Foreign Secretary in October 1900, Delcassé was once again initially optimistic the chances for rapprochement had improved.

Landsdowne.

Manchester Guardian and the Speaker published articles questioning whether an Anglo-French agreement would be worth the complications for the broader power arrangements that would surely follow. Detenté could on no account be allowed to stand in the way of other alliances, even with Germany, and should serve instead as the starting point for a whole network of treaties. Gladstonian idea of the old Concert of Powers was alive and well, contesting the ideas of secretive balance of power deals or open power blocks that would leave core members of the state's system cornered and encircled.

The Manchester Guardian.

Just a couple of nitpicks.

Excellent updates. Delcassé was an interesting character, wasn't he? Such an odd mix of perceptiveness and paranoia.

Thanks for pointing this out.This post and many others are walls of black on dark mode

One gets unaware of such errors in longer texts, so thanks for pointing them out.Just a couple of nitpicks.

He certainly was, and the men he chose for leading positions in the French diplomacy of the day were also far from dull.Excellent updates. Delcassé was an interesting character, wasn't he? Such an odd mix of perceptiveness and paranoia.

Chapter 180: Anglo-French relations, part 6: "If firefly, don't vie with fire"

The French and British expansion in Indochina and the Malay peninsula during the latter half of the nineteenth century had culminated in 1885 with French occupation of Tonkin and Annam, and the British conquest of Theebaw's kingdom, Upper Burma, and Malay areas.

Now confronted by British Malaya and British Burma on the south and west and French Indo-China on the east, the Buddhist kingdom of Siam was by year 1900 regarded by the British imperialists as an eastern counterpart of Afghanistan. It was tasked to exist at the mercy of the Europeans as a nominally independent buffer state of the British Raj in India.

While willing to keep Siam on map as a separate entity, the British had not yet made up their minds about the potential direct annexations of certain Siamese-controlled border areas of British Malaya and Burma.

The British businessmen had from the start viewed the fertile rice fields, unexploited tin deposits and other mineral wealth such as teak forests of Siam with greedy eyes. Step by step they had established effective control of most of the local shipping, industry, banking and trade.

British “advisors” had filled the ranks of the Siamese administration and court, as lesser princes and sons of prominent nobles had flocked to Eton and other universities in Britain. Soon one could talk English to practically every prominent member of high society and upper ranks of government in Bangkok.

Meanwhile the French authorities in Indochina and back home had had their own plans. After the Sino-French War of 1884-85, the French had opened Yunnan for trade at gunpoint. The aim of the French Indochinese Governor-General Paul Doumer had been - and still was - to turn the Southeast Asian colonies from costly money sinks into a profitable business by any means necessary. Capturing the commerce of southwestern China to reduce the perennial Tonkin trade deficit and to support local industrialization had been deemed vital for this goal.

And to keep the trade growing with a steady flow of tin and opium from Yunnan, China had to be kept at peace. A belt of French puppet states around the colonial core of Indochina was deemed necessary. They would form a necessary protective buffer zone and the best guarantee against future disorders in China, while also keeping the British competitors at bay.

Far away in Paris, Foreign Minister Delcassé had started to pursue his own policies (in secrecy of course), focused on strengthening the French presence in Africa. For this he had needed peace in Asia and an accord with London. Only vaguely aware of Hanoi's intentions, however, the home government had not done more than dispatched occasional muted admonitions to Doumer.