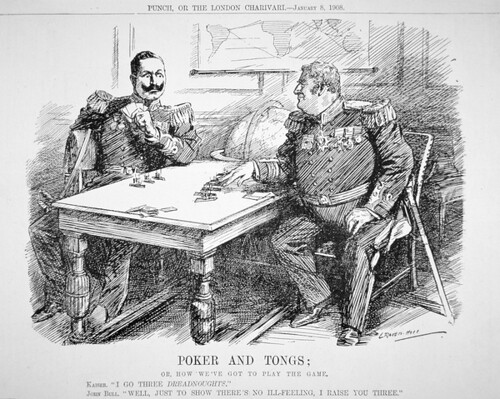

The meeting turned from cordial discussion into a heated debate. Tirpitz had to admit that right now he could not promise decisive success in a decisive battle against the Royal Navy. In a case of war the German foreign trade would be blockaded, August von Heeringen stated, and there was little the Navy could do to change this considering the overall geography. The British had the luxury to either choose a distant blockade or go for an aggressive close blockade, whereas the German Navy lacked strength to challenge either posture.[

1]

Von Beseler did not miss the chance for a sardonic remark. Since now was obviously a bad time,

when exactly would the Navy be ready then? Just like Field Marshall von Waldersee had said already in 1898, the navy kept cultivating the notion that future wars would be decided at sea. But

what exactly did the navy propose to do if the army suffered a defeat, be it in the West or in the East?

Here the two factions of German military found little room for compromise: Beseler wanted more divisions and revision of available funding, while Tirpitz would not give up with his idea that the

Hochseeflotte would

ultimately become an important deterrent against the threat of a British blockade - but when pressed on the exact timetable, the irritated old sea lion was unable to provide anything concrete.

Posadowsky was appalled.

Two days later the Chancellor invited von Beseler, von der Goltz, War Minister von Heeringen and the State Secretary of Finance Adolf Wehrmuth to meet him in private. Chancellor Posadowsky stated outright that the current war plans were a road to ruin and totally out of touch with the basic facts of

Realpolitik.

The old agrarian made von Beseler an offer he could ill refuse: Firstly, he wanted an ally to wean the young Kaiser away from Tirpitz and the navalists, and promised more funding for the army in return. Secondly, since it was clear that Tirpitz could never deliver what he kept promising, antagonizing the British by invading Belgium would turn a war against France into a struggle against the very kind of nightmare coalition Bismarck had warned about.

There had to be an alternative course of action, and Posadowsky said that the Emperor wanted to see a concrete plan for it as soon as possible. Von der Goltz, an old warhorse and anglophobe Pan-German as he was, supported this notion - knowing fully well that the young Kaiser had no idea that this meeting was taking place. The old general was not against naval expansion

per se, on the contrary, but he had for long advocated for expanded funding for the Army.[

2]

War Minister von Heeringen was a loyal mandarin and supported the Clausewitzian idea of the primacy of the civilian government, while State Secretary of Finance Wehrmuth just wanted to get the rampart spending spree in check, merely remarking: “

As the strength of the army is for us a matter of life and death, so is the fleet for England.”[

3]

And thus the civilians and soldiers formed a temporary marriage of convenience. The preliminary drafts from von Beseler were ready after a month of work. It had two variants, for French aggression and Russian aggression each, with either one of the hostile powers initially in an undetermined political position. Both plans showed that they were devised by a military engineer and the former Inspector of Fortresses: they called for strong fortress lines at the western and eastern border of Germany, and von Beseler openly stated that it would require a lot of new standing army formations and funding to turn the drafts into a viable strategic options.

Posadowsky realized that this was finally it: Germany was facing a strategic choice she had postponed for far too long.

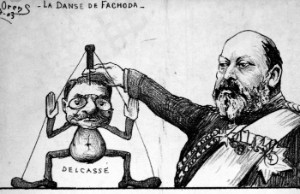

For the previous decade Tirpitz had bypassed the tangled mess of conflicting Reichstag interests by using extra-parliamentary lobby groups of his own to influence the parties from the outside. Zentrum deputies had helped him to pass the first two Navy Laws, but already before his downfall Chancellor Eulenburg had found it harder and harder to sustain the alliance of moderate agrarians and industrialists who had so far allowed Wilhelm II and Tirpitz to continue the grandiose naval plans.

His predecessors had merely kept kicking the can down the road. Posadowsky no longer had neither the necessary tax funds or Reichstag votes for such luxury. Germany could no longer afford to maintain a strong standing army, invest in the unprofitable colonies, and constantly expand the naval budget, especially since the populist wing of Zentrum led by Matthias Erzberger was now openly critical to the naval policy of Tirpitz. Something had to change, since there simply wasn’t enough funding to keep all grandiose plans of Wilhelm II up and running anymore.

Posadowsky presented this state of affairs to Wilhelm III in a most courteous manner. He was friendly, but firm, and had a simple message: Further naval laws were no longer a realistic possibility. He requested from the new All-Highest that in order to save what might still be saved from the noble legacy of His Majesty Wilhelm II, the Foreign Office should be given a chance to at least try to negotiate some sort of a face-saving naval

détente with Britain.

For his part, Wilhelm III never found it odd that the Chief of Staff, Chief of the Military Cabinet, Finance Minister, Foreign Minister and Chancellor all advocated roughly similar courses of action when he asked for their opinion during the following days. Had he not always loved the Army more than the Navy after all, and wanted to try to find at least some common ground with Britain, if possible?

Tirpitz, for his part, was not so easily fooled. He knew that the son was unlike his father, and realized that the way the Navy received almost half of the total defense expenditures of Germany was not a state of affairs that could be justified easily with the new monarch.

Even though he never admitted it frankly and openly, his blueprint for Weltpolitik had failed the moment

HMS Dreadnought had been launched. Existing locks and docks in the major German naval bases required extensive rework to handle the increases in displacement, the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Kanal had to be both widened and deepened: in total the changes in technology increased the costs of up-to-date battleships by 96% and battlecruisers by 107%!

His staff had made calculations that kept Tirpitz awake at night. Naval estimates of 347 million for 1908 would have to rise to at least 434 million GM by 1910 to maintain the planned expansion rate (that would most likely not be enough to keep up with the Royal Navy), and the Reich Treasury would have to raise 1 000 million GM in new indirect taxation for Germany to continue the dreadnought race.

And no matter how Tirpitz tried to spin these numbers, he remarked to his staff in private that the cost of individual ships “

had reached impossible heights for Reich finances and will continue to do so.”[

4] To make matters even worse, the German shipyards were simply not up to the task of challenging their British counterparts. Competition schedules were constantly delayed, and the major shipyards were hard-pressed to keep up in the international competition for civilian vessels.

The humiliating experience of 1905 when the British naval forces descended to the Baltic and North Sea coast in an open display of prowess of the Royal Navy had driven the point home for most of the German elite. The old fear - “

Der Fischer kommt” had turned to reality. It was one thing to read about the British naval power and look at statistics, and quite another to actually see their battleships at sea all along the coasts of Germany.

With the prospect of a new naval law being particularly nil considering the views of the new Chancellor, mood in the Reichstag and the country at large and the ambivalence of the young Emperor, Tirpitz surprised Wilhelm III when he was summoned to discuss "

vital questions of naval strategy." He started by stating that he, too, supported a greatly expanded army bill. This did little to warm Wilhelm III to the still adamant view of the Admiral regarding the vital necessity of continued naval construction, but further improved his personal view of Tirpitz in the eyes of the young Emperor.

But it was not enough. Vultures had already began to descent. Chief of the Naval Cabinet, von Müller, now advocated the view that the delay of the 1908 naval funding had already given the Royal Navy too much of a head-start, and ruined German prospects of a prolonged naval arms race. Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff wrote a widely-discussed article to

Die Flotte, the Navy League monthly, publicly hoping that the Navy would focus on readiness issues - for what good were new ships without trained crews? Tirpitz had made sure that he held all the reins during the time of Wilhelm II, and had used his elbows to make sure he remained the top dog in German naval strategy. Now he found himself surrounded by greedy competitors who showed scant mercy.

The Treasury was desperate to cut expenses, Posadowsky wanted to placate his Agrarian supporters by focusing on the Army, and hoped against hope that he could turn necessity into virtue by still seeking some kind of a deal with Britain. When met with an alliance of dissident admirals, vengeful generals and thrifty politicians surrounding the inexperienced and ambivalent young Emperor, Tirpitz offered his resignation.

But Wilhelm III would not have it. He greatly valued Tirpitz as an individual, as he explained to the downtrodden navalist, and added that he was certain that He and Germany would yet need the good services of Admiral in the future. He insisted that Tirpitz remained in office, as the Emperor wanted him to remain in the Landesverteidigunsgkomission.[

5]

1.

OTL assessment, which was historically kept a secret from the Army and politicians.

2.

Colmar von der Goltz met the Crown Prince in Eastern Prussia during his tenure as commander of the I Corps both in TTL and OTL, and was posted to Berlin the same time when the Crown Prince started his studies there in 1907. His hardliner Pan-German views closely match those of the Crown Prince, who adores people who dare to say what they think. Hence he became the new Chief of the Military Cabinet after the death of Hülsen-Haeseler. The OTL replacement, Moritz von Lyncker was the officer in charge of the education of the Crown Prince, and his memoirs make it clear that he would have never assigned his former tutor to such a post.

3.

OTL quote.

4.

All figures are from OTL, and Tirpitz really said this to his staff.

5.

Crown Prince Wilhelm greatly liked Tirpitz because of his middle-class background and professional mindset, even though he was never the navalist his father was.