Chapter 796: The Evolution of Coprospism and the Co-Prosperity Sphere trough Japanese History

After two centuries, the seclusion policy, or sakoku, under the shōguns of the Edo period came to an end when the country was forced open to trade by the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854. Thus, the period known as Bakumatsu began. The following years saw increased foreign trade and interaction; commercial treaties between the Tokugawa shogunate and Western countries were signed. In large part due to the humiliating terms of these unequal treaties, the shogunate soon faced internal hostility, which materialized into a radical, xenophobic movement, the sonnō jōi (literally "Revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians"). In March 1863, the Emperor issued the "order to expel barbarians". Although the shogunate had no intention of enforcing the order, it nevertheless inspired attacks against the shogunate itself and against foreigners in Japan. The Namamugi Incident during 1862 led to the murder of an Englishman, Charles Lennox Richardson, by a party of samurai from Satsuma. The British demanded reparations but were denied. While attempting to exact payment, the Royal Navy was fired on from coastal batteries near the town of Kagoshima. They responded by bombarding the port of Kagoshima in 1863. The Tokugawa government agreed to pay an indemnity for Richardson's death. Shelling of foreign shipping in Shimonoseki and attacks against foreign property led to the bombardment of Shimonoseki by a multinational force in 1864. The Chōshū clan also launched the failed coup known as the Kinmon incident. The Satsuma-Chōshū alliance was established in 1866 to combine their efforts to overthrow the Tokugawa bakufu. In early 1867, Emperor Kōmei died of smallpox and was replaced by his son, Crown Prince Mutsuhito (Meiji). On November 9, 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu resigned from his post and authorities to the Emperor, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders. The Tokugawa shogunate had ended. However, while Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist.

Moreover, the shogunal government, the Tokugawa family in particular, remained a prominent force in the evolving political order and retained many executive powers, a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable. On January 3, 1868, Satsuma-Chōshū forces seized the imperial palace in Kyoto, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old Emperor Meiji declare his own restoration to full power. Although the majority of the imperial consultative assembly was happy with the formal declaration of direct rule by the court and tended to support a continued collaboration with the Tokugawa, Saigō Takamori threatened the assembly into abolishing the title shōgun and ordered the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands. On January 17, 1868, Yoshinobu declared "that he would not be bound by the proclamation of the Restoration and called on the court to rescind it". On January 24, Yoshinobu decided to prepare an attack on Kyoto, occupied by Satsuma and Chōshū forces. This decision was prompted by his learning of a series of arson attacks in Edo, starting with the burning of the outworks of Edo Castle, the main Tokugawa residence.

The Boshin War (戊辰戦争, Boshin Sensō) was fought between January 1868 and May 1869. The alliance of samurai from southern and western domains and court officials had now secured the cooperation of the young Emperor Meiji, who ordered the dissolution of the two-hundred-year-old Tokugawa shogunate. Tokugawa Yoshinobu launched a military campaign to seize the emperor's court at Kyoto. However, the tide rapidly turned in favor of the smaller but relatively modernized imperial faction and resulted in defections of many daimyōs to the Imperial side. The Battle of Toba–Fushimi was a decisive victory in which a combined army from Chōshū, Tosa, and Satsuma domains defeated the Tokugawa army. A series of battles were then fought in pursuit of supporters of the Shogunate; Edo surrendered to the Imperial forces and afterwards Yoshinobu personally surrendered. Yoshinobu was stripped of all his power by Emperor Meiji and most of Japan accepted the emperor's rule.

Pro-Tokugawa remnants, however, then retreated to northern Honshū (Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei) and later to Ezo (present-day Hokkaidō), where they established the breakaway Republic of Ezo. An expeditionary force was dispatched by the new government and the Ezo Republic forces were overwhelmed. The siege of Hakodate came to an end in May 1869 and the remaining forces surrendered. Japan had learned that if it wished to dictate it's own future and be protected from outside interference in it's state, culture, religion and way of life it had to modernize itself to be on pair with the outside, foreign powers that since the Dutch the middle ages had tried to break into Japanese isolationism, with their own culture, trade, economics and even religions, like they had done to so many nations that had become colonies ever since. The ideal of Coprospism had been born.

The Charter Oath was made public at the enthronement of Emperor Meiji of Japan on April 7, 1868. The Oath outlined the main aims and the course of action to be followed during Emperor Meiji's reign, setting the legal stage for Japan's modernization. The Meiji leaders also aimed to boost morale and win financial support for the new government. Japan dispatched the Iwakura Mission in 1871. The mission traveled the world in order to renegotiate the unequal treaties with the United States and European countries that Japan had been forced into during the Tokugawa shogunate, and to gather information on western social and economic systems, in order to effect the modernization of Japan. Renegotiation of the unequal treaties was universally unsuccessful, but close observation of the American and European systems inspired members on their return to bring about modernization initiatives in Japan. Japan made a territorial delimitation treaty with Russia in 1875, gaining all the Kuril islands in exchange for Sakhalin island, a deal not all Japanese favored. The Japanese government sent observers to Western countries to observe and learn their practices, and also paid "foreign advisors" in a variety of fields to come to Japan to educate the populace. For instance, the judicial system and constitution were largely modeled on those of Prussia. The government also outlawed customs linked to Japan's feudal past, such as publicly displaying and wearing katana and the top knot, both of which were characteristic of the samurai class, which was abolished together with the caste system. This would later bring the Meiji government into conflict with the samurai. Several writers, under the constant threat of assassination from their political foes, were influential in winning Japanese support for westernization. One such writer was Fukuzawa Yukichi, whose works included "Conditions in the West," "Leaving Asia", and "An Outline of a Theory of Civilization," which detailed Western society and his own philosophies. In the Meiji Restoration period, military and economic power was emphasized. Military strength became the means for national development and stability. Imperial Japan became the only non-Western world power and a major force in East Asia in about 25 years as a result of industrialization and economic development. The rise of Japan to a world power during these years is the greatest miracle in world history. The mighty empires of antiquity, the major political institutions of the Middle Ages and the early modern era, the Spanish Empire, the British Empire, yes even the French Empire and the German Empire as well as the United States all needed centuries to achieve their full strength. Japan's rise has been meteoric. After only a few years, it is one of the few great powers that determine the fate of the world and on the rise of dominating it completely during the Second Great War many Japanese felt.

In the 1860s, Japan began to experience great social turmoil and rapid modernization. The feudal caste system in Japan formally ended in 1869 with the Meiji restoration. In 1871, the newly formed Meiji government issued a decree called Senmin Haishirei (賤民廃止令 Edict Abolishing Ignoble Classes) giving outcasts equal legal status. It is currently better known as the Kaihōrei (解放令 Emancipation Edict). However, the elimination of their economic monopolies over certain occupations actually led to a decline in their general living standards, while social discrimination simply continued. For example, the ban on consumption of meat from livestock was lifted in 1871, and many former eta moved on to work in abattoirs and as butchers. However, slow-changing social attitudes, especially in the countryside, meant that abattoirs and workers were met with hostility from local residents. Continued ostracism as well as the decline in living standards led to former eta communities turning into slum areas. The social tension continued to grow during the Meiji period, affecting religious practices and institutions. Conversion from traditional faith was no longer legally forbidden, officials lifted the 250-year ban on Christianity, and missionaries of established Christian churches reentered Japan. The traditional syncreticism between Shinto and Buddhism ended for a short period of time. Losing the protection of the Japanese government which Buddhism had enjoyed for centuries, Buddhist monks faced radical difficulties in sustaining their institutions, but their activities also became less restrained by governmental policies and restrictions. As social conflicts emerged in this last decade of the Edo period, some new religious movements appeared, which were directly influenced by shamanism and Shinto.

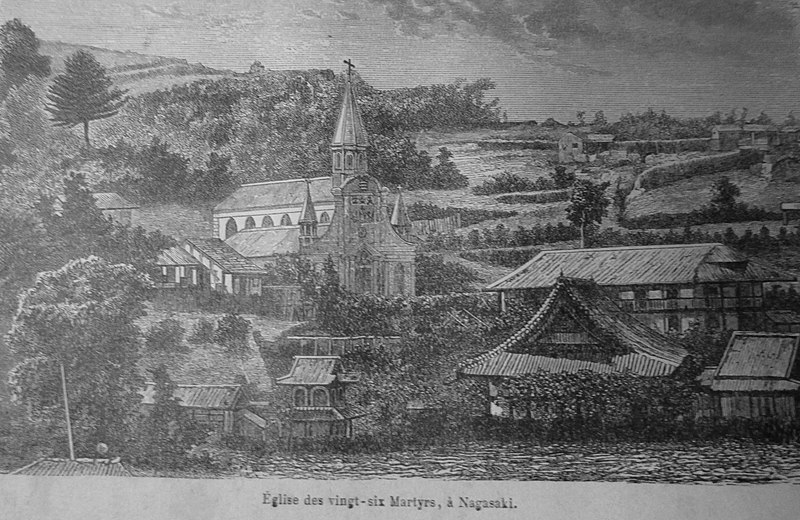

Emperor Ogimachi issued edicts to ban Catholicism in 1565 and 1568, but to little effect. Beginning in 1587 with imperial regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi's ban on Jesuit missionaries, Christianity was repressed as a threat to national unity. Under Hideyoshi and the succeeding Tokugawa shogunate, Catholic Christianity was repressed and adherents were persecuted. After the Tokugawa shogunate banned Christianity in 1620, it ceased to exist publicly. Many Catholics went underground, becoming hidden Christians (隠れキリシタン, kakure kirishitan), while others lost their lives. After Japan was opened to foreign powers in 1853, many Christian clergymen were sent from Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox churches, though proselytism was still banned. Only after the Meiji Restoration, was Christianity re-established in Japan. Freedom of religion was introduced in 1871, giving all Christian communities the right to legal existence and preaching. Eastern Orthodoxy was brought to Japan in the 19th century by St. Nicholas (baptized as Ivan Dmitrievich Kasatkin), who was sent in 1861 by the Russian Orthodox Church to Hakodate, Hokkaidō as priest to a chapel of the Russian Consulate. St. Nicholas of Japan made his own translation of the New Testament and some other religious books (Lenten Triodion, Pentecostarion, Feast Services, Book of Psalms, Irmologion) into Japanese. Nicholas has since been canonized as a saint by the Patriarchate of Moscow in 1950, and is now recognized as St. Nicholas, Equal-to-the-Apostles to Japan. His commemoration day is February 16. Andronic Nikolsky, appointed the first Bishop of Kyoto and later martyred as the archbishop of Perm during the Russian Revolution, was also canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church as a Saint and Martyr in the year 1960.

Divie Bethune McCartee was the first ordained Presbyterian minister missionary to visit Japan, in 1861–1862. His gospel tract translated into Japanese was among the first Protestant literature in Japan. In 1865, McCartee moved back to Ningbo, China, but others have followed in his footsteps. There was a burst of growth of Christianity in the late 19th century when Japan re-opened its doors to the West. Protestant church growth slowed dramatically in the early 20th century under the influence of the military government during the Shōwa period. During the early 20th century, the government was suspicious towards a number of unauthorized religious movements and periodically made attempts to suppress them. Government suppression was especially severe from the 1930s until the early 1940s, when the growth of Japanese nationalism and State Shinto were closely linked. Under the Meiji regime lèse majesté prohibited insults against the Emperor and his Imperial House, and also against some major Shinto shrines which were believed to be tied strongly to the Emperor. The government strengthened its control over religious institutions that were considered to undermine State Shinto or nationalism and began seeing foreign religion as instruments of foreign powers to gain influence in Japan as well, soemthign it would later try with it's own Buddhist-SHinto religion in Asia and the Pacific itself.

The idea of a written constitution had been a subject of heated debate within and outside of the government since the beginnings of the Meiji government. The conservative Meiji oligarchy viewed anything resembling democracy or republicanism with suspicion and trepidation, and favored a gradualist approach. The Freedom and People's Rights Movement demanded the immediate establishment of an elected national assembly, and the promulgation of a constitution. The constitution recognized the need for change and modernization after removal of the shogunate:

We, the Successor to the prosperous Throne of Our Predecessors, do humbly and solemnly swear to the Imperial Founder of Our House and to Our other Imperial Ancestors that, in pursuance of a great policy co-extensive with the Heavens and with the Earth, We shall maintain and secure from decline the ancient form of government. ... In consideration of the progressive tendency of the course of human affairs and in parallel with the advance of civilization, We deem it expedient, in order to give clearness and distinctness to the instructions bequeathed by the Imperial Founder of Our House and by Our other Imperial Ancestors, to establish fundamental laws. Imperial Japan was founded, de jure, after the 1889 signing of Constitution of the Empire of Japan. The constitution formalized much of the Empire's political structure and gave many responsibilities and powers to the Emperor.

- Article 4. The Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the present Constitution.

- Article 6. The Emperor gives sanction to laws, and orders them to be promulgated and executed.

- Article 11. The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and Navy.

In 1890, the Imperial Diet was established in response to the Meiji Constitution. The Diet consisted of the House of Representatives of Japan and the House of Peers. Both houses opened seats for colonial people as well as Japanese. heavily subsidized by the Meiji government in close connection with a powerful clique of companies known as zaibatsu (e.g.: Mitsui and Mitsubishi). Borrowing and adapting technology from the West, Japan gradually took control of much of Asia's market for manufactured goods, beginning with textiles. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products, a reflection of Japan's relative scarcity of raw materials.

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. The government was initially involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period. The transition took time. By the 1890s, however, the Meiji had successfully established a modern institutional framework that would transform Japan into an advanced capitalist economy. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons. Many of the former daimyōs, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa-Meiji transition as an industrialized nation. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. Rapid growth and structural change characterized Japan's two periods of economic development after 1868. Initially, the economy grew only moderately and relied heavily on traditional Japanese agriculture to finance modern industrial infrastructure. By the time the Russo-Japanese War began in 1904, 65% of employment and 38% of the gross domestic product (GDP) were still based on agriculture, but modern industry had begun to expand substantially. By the late 1920s, manufacturing and mining amounted to 34% of GDP, compared with 20% for all of agriculture. Transportation and communications developed to sustain heavy industrial development.

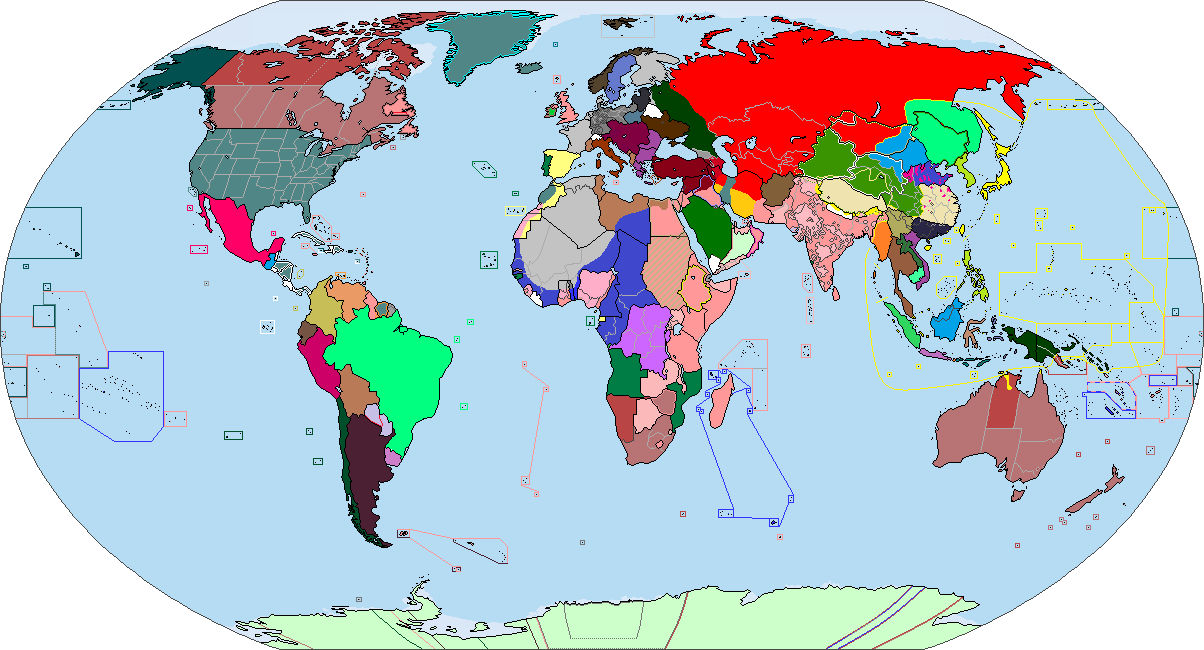

From 1894, Japan built an extensive empire that included Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and parts of northern China, the beginning of their claims to those areas. The Japanese regarded this sphere of influence as a political and economic necessity, which would prevented foreign states from strangling Japan by blocking its access to raw materials and crucial sea-lanes to influence it's internal order and politics. Japan's large military force was regarded as essential to the empire's defense and prosperity by obtaining natural resources that the Japanese islands lacked.

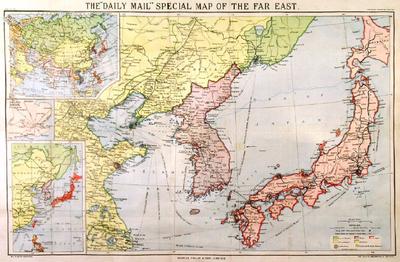

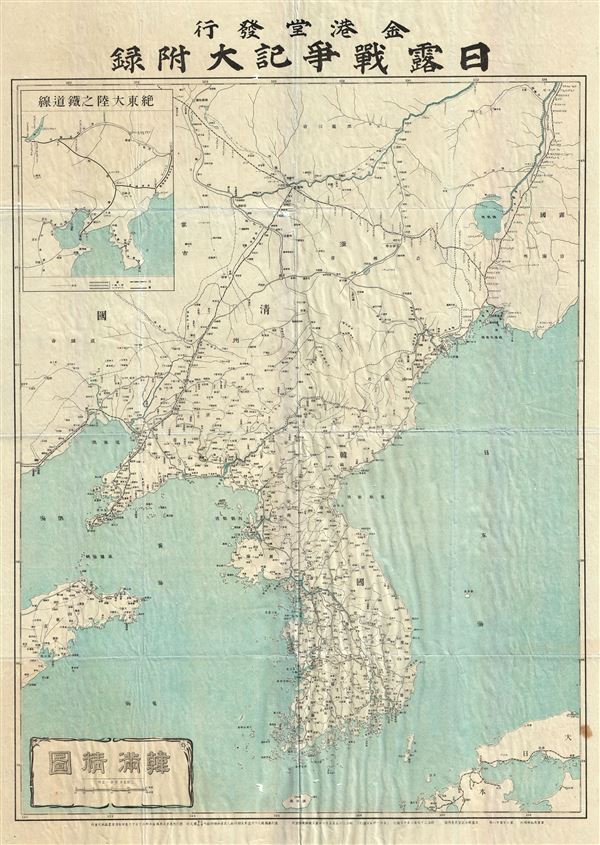

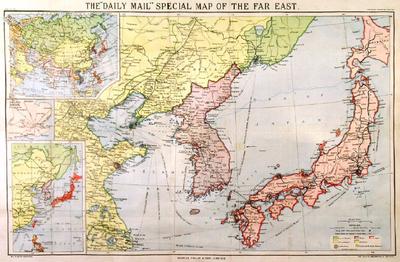

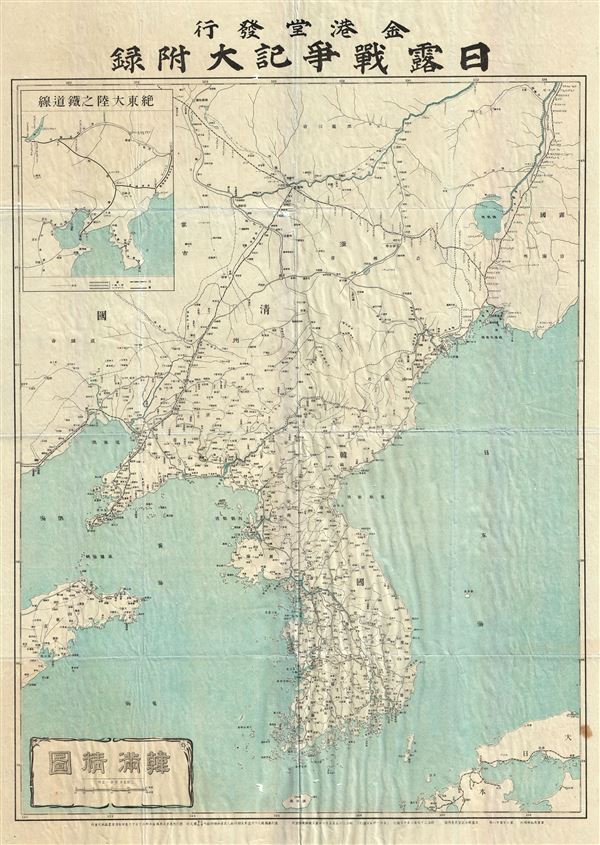

The First Sino-Japanese War, fought in 1894 and 1895, revolved around the issue of control and influence over Korea under the rule of the Joseon Dynasty. Korea had traditionally been a tributary state of China's Qing Empire, which exerted large influence over the conservative Korean officials who gathered around the royal family of the Joseon kingdom. On February 27, 1876, after several confrontations between Korean isolationists and Japanese, Japan imposed the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, forcing Korea open to Japanese trade. The act blocks any other power from dominating Korea, resolving to end the centuries-old Chinese suzerainty. On June 4, 1894, Korea requested aid from the Qing Empire in suppressing the Donghak Rebellion. The Qing government sent 2,800 troops to Korea. The Japanese countered by sending an 8,000-troop expeditionary force (the Oshima Composite Brigade) to Korea. The first 400 troops arrived on June 9 en route to Seoul, and 3,000 landed at Incheon on June 12.[33] The Qing government turned down Japan's suggestion for Japan and China to cooperate to reform the Korean government. When Korea demanded that Japan withdraw its troops from Korea, the Japanese refused. In early June 1894, the 8,000 Japanese troops captured the Korean king Gojong, occupied the Royal Palace in Seoul and, by June 25, installed a puppet government in Seoul. The new pro-Japanese Korean government granted Japan the right to expel Qing forces while Japan dispatched more troops to Korea. China objected and war ensued. Japanese ground troops routed the Chinese forces on the Liaodong Peninsula, and nearly destroyed the Chinese navy in the Battle of the Yalu River. The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed between Japan and China, which ceded the Liaodong Peninsula and the island of Taiwan to Japan. After the peace treaty, Russia, Germany, and France forced Japan to withdraw from Liaodong Peninsula and use China's weakened position to gain more influence after Japan had defeated them. Soon afterwards the European Powers used the situation that Japan had weakened China and divided it into their own Sphere's of Influence, the very same think they had denied Japan after it's victory. Russia occupied the Liaodong Peninsula, built the Port Arthur fortress, and based the Russian Pacific Fleet in the port. Germany occupied Jiaozhou Bay, built Tsingtao fortress and based the German East Asia Squadron in this port.

In 1900, Japan joined an international military coalition set up in response to the Boxer Rebellion in the Qing Empire of China. Japan provided the largest contingent of troops: 20,840, as well as 18 warships. Of the total, 20,300 were Imperial Japanese Army troops of the 5th Infantry Division under Lt. General Yamaguchi Motoomi; the remainder were 540 naval rikusentai (marines) from the Imperial Japanese Navy. At the beginning of the Boxer Rebellion the Japanese only had 215 troops in northern China stationed at Tientsin; nearly all of them were naval rikusentai from the Kasagi and the Atago, under the command of Captain Shimamura Hayao. The Japanese were able to contribute 52 men to the Seymour Expedition. On June 12, 1900, the advance of the Seymour Expedition was halted some 50 kilometres (30 mi) from the capital, by mixed Boxer and Chinese regular army forces. The vastly outnumbered allies withdrew to the vicinity of Tianjin, having suffered more than 300 casualties. The army general staff in Tokyo had become aware of the worsening conditions in China and had drafted ambitious contingency plans, but in the wake of the Triple Intervention five years before, the government refused to deploy large numbers of troops unless requested by the western powers. However three days later, a provisional force of 1,300 troops commanded by Major General Fukushima Yasumasa was to be deployed to northern China. Fukushima was chosen because he spoke fluent English which enabled him to communicate with the British commander. The force landed near Tianjin on July 5. On June 17, 1900, naval Rikusentai from the Kasagi and Atago had joined British, Russian, and German sailors to seize the Dagu forts near Tianjin. In light of the precarious situation, the British were compelled to ask Japan for additional reinforcements, as the Japanese had the only readily available forces in the region. Britain at the time was heavily engaged in the Boer War, so a large part of the British army was tied down in South Africa. Further, deploying large numbers of troops from its garrisons in India would take too much time and weaken internal security there.

Overriding personal doubts, Foreign Minister Aoki Shūzō calculated that the advantages of participating in an allied coalition were too attractive to ignore. Prime Minister Yamagata agreed, but others in the cabinet demanded that there be guarantees from the British in return for the risks and costs of the major deployment of Japanese troops. On July 6, 1900, the 5th Infantry Division was alerted for possible deployment to China, but no timetable was set for this. Two days later, with more ground troops urgently needed to lift the siege of the foreign legations at Peking, the British ambassador offered the Japanese government one million British pounds in exchange for Japanese participation. Shortly afterward, advance units of the 5th Division departed for China, bringing Japanese strength to 3,800 personnel out of the 17,000 of allied forces. The commander of the 5th Division, Lt. General Yamaguchi Motoomi, had taken operational control from Fukushima. Japanese troops were involved in the storming of Tianjin on July 14, after which the allies consolidated and awaited the remainder of the 5th Division and other coalition reinforcements. By the time the siege of legations was lifted on August 14, 1900, the Japanese force of 13,000 was the largest single contingent and made up about 40% of the approximately 33,000 strong allied expeditionary force. Japanese troops involved in the fighting had acquitted themselves well, although a British military observer felt their aggressiveness, densely-packed formations, and over-willingness to attack cost them excessive and disproportionate casualties.During the Tianjin fighting alone, the Japanese suffered more than half of the allied casualties (400 out of 730) but comprised less than one quarter (3,800) of the force of 17,000. Similarly at Beijing, the Japanese accounted for almost two-thirds of the losses (280 of 453) even though they constituted slightly less than half of the assault force. After the uprising, Japan and the Western countries signed the Boxer Protocol with China, which permitted them to station troops on Chinese soil to protect their citizens. After the treaty, Russia continued to occupy all of Manchuria and thereby endanger Japanese trade interest and political influence in the area, as well as in nearby Korea.

The Russo-Japanese War was a conflict for control of Korea and parts of Manchuria between the Russian Empire and Empire of Japan that took place from 1904 to 1905. The victory greatly raised Japan's stature in the world of global politics. The war is marked by the Japanese opposition of Russian interests in Korea, Manchuria, and China, notably, the Liaodong Peninsula, controlled by the city of Ryojun. Originally, in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, Ryojun had been given to Japan. This part of the treaty was overruled by Western powers, which gave the port to the Russian Empire, furthering Russian interests in the region. These interests came into conflict with Japanese interests and further alienating and antagonizing the Japanese who once again felt cut short and betrayed by the Western Powers. The war began with a surprise attack on the Russian Eastern fleet stationed at Port Arthur, which was followed by the Battle of Port Arthur. Those elements that attempted escape were defeated by the Japanese navy under Admiral Togo Heihachiro at the Battle of the Yellow Sea. Following a late start, the Russian Baltic fleet was denied passage through the British-controlled Suez Canal. The fleet arrived on the scene a year later, only to be annihilated in the Battle of Tsushima. While the ground war did not fare as poorly for the Russians, the Japanese forces were significantly more aggressive than their Russian counterparts and gained a political advantage that culminated with the Treaty of Portsmouth, negotiated in the United States by the American president Theodore Roosevelt. As a result, Russia lost the part of Sakhalin Island south of 50 degrees North latitude (which became Karafuto Prefecture), as well as many mineral rights in Manchuria. In addition, Russia's defeat cleared the way for Japan to annex Korea outright in 1910. The Japanese however had hoped to gain all of Karafuto/ Sakhalin Island and their rights in Manchuria guaranteed and therefore felt once more betrayed by a foreign Western Power, this time the United States negotiation, as the Japanese felt they benefited Russia. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, various Western countries actively competed for influence, trade, and territory in East Asia, and Japan sought to join these modern colonial powers. The newly modernised Meiji government of Japan turned to Korea, then in the sphere of influence of China's Qing dynasty. The Japanese government initially sought to separate Korea from Qing and make Korea a Japanese satellite in order to further their security and national interests.

In January 1876, following the Meiji Restoration, Japan employed gunboat diplomacy to pressure the Joseon Dynasty into signing the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, which granted extraterritorial rights to Japanese citizens and opened three Korean ports to Japanese trade. The rights granted to Japan under this unequal treaty, were similar to those granted western powers in Japan following the visit of Commodore Perry. Japanese involvement in Korea increased during the 1890s, a period of political upheaval. Korea was occupied and declared a Japanese protectorate following the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905. After proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire, Korea was officially annexed in Japan through the annexation treaty in 1910. Japan afterwards entered the Great War on the side of the Allies in 1914, because of their Alliance with Britain, seizing the opportunity of Germany's distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Japan declared war on Germany on August 23, 1914. Japanese and allied British Empire forces soon moved to occupy Tsingtao fortress, the German East Asia Squadron base, German-leased territories in China's Shandong Province as well as the Marianas, Caroline, and Marshall Islands in the Pacific, which were part of German New Guinea. The swift invasion in the German territory of the Kiautschou Bay concession and the Siege of Tsingtao proved successful. The German colonial troops surrendered on November 7, 1914, and Japan gained the German holdings. With its Western allies, notably the United Kingdom, heavily involved in the war in Europe, Japan dispatched a Naval fleet to the Mediterranean Sea to aid Allied shipping. Japan sought further to consolidate its position in China by presenting the Twenty-One Demands to China in January 1915. In the face of slow negotiations with the Chinese government, widespread anti-Japanese sentiment in China, and international condemnation, Japan withdrew the final group of demands, and treaties were signed in May 1915. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, before its demise in 1921. It was officially terminated in 1923. The fact that the Japanese were not granted all of the German Colonies in Asia and the Pacific for their support in the Great War once again let them feel betrayed by the European Powers, this time even their own allies. Japan had also witnessed how the British Used their Empire, mainly it's semi-autonomous Dominions to grab more Mandates of the newly formed League of Nation then any other nations, something that would give further rise to Coprospist Ideals and National Independence movements in Chosen (Korea) and Japan later on.

After the fall of the Tsarist regime and the later provisional regime in 1917, the new Bolshevik government signed a separate peace treaty with Germany. After this the Russians fought amongst themselves in a multi-sided civil war. In July 1918, President Wilson asked the Japanese government to supply 7,000 troops as part of an international coalition of 25,000 troops planned to support the American Expeditionary Force Siberia. Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake agreed to send 12,000 troops but under the Japanese command rather than as part of an international coalition. The Japanese had several hidden motives for the venture, which included an intense hostility and fear of communism; a determination to recoup historical losses to Russia; and the desire to settle the "northern problem" in Japan's security, either through the creation of a buffer state or through outright territorial acquisition. By November 1918, more than 70,000 Japanese troops under Chief of Staff Yui Mitsue had occupied all ports and major towns in the Russian Maritime Provinces and eastern Siberia and the Island of Karafuto. Japan received 765 Polish orphans from Siberia. In June 1920, around 450 Japanese civilians and 350 Japanese soldiers, along with Russian White Army supporters, were massacred by partisan forces associated with the Red Army at Nikolayevsk on the Amur River; the United States and its allied coalition partners consequently withdrew from Vladivostok after the capture and execution of White Army leader Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak by the Red Army. However, the Japanese decided to stay, primarily due to fears of the spread of Communism so close to Japan and Japanese-controlled Korea and Manchuria. The Japanese army provided military support to the Japanese-backed Provisional Priamurye Government based in Vladivostok against the Moscow-backed Far Eastern Republic. The continued Japanese presence concerned the United States, which suspected that Japan had territorial designs on Siberia and the Russian Far East. Subjected to intense diplomatic pressure by the United States and United Kingdom, and facing increasing domestic opposition due to the economic and human cost, the administration of Prime Minister Katō Tomosaburō withdrew the Japanese forces in October 1922. Japanese casualties from the expedition were 5,000 dead from combat or illness, with the expedition costing over 900 million yen. And thanks to the Americans and British no gains in the Far East, not even North Karafuto could be made, once again proving that both nations, while expanding all over the Americas or the World, tried to prevent any form of Japanese growth overall.

The two-party political system that had been developing in Japan since the turn of the century came of age after the Great War, giving rise to the nickname for the period, "Taishō Democracy". The public grew disillusioned with the growing national debt and the new election laws, which retained the old minimum tax qualifications for voters. Calls were raised for universal suffrage and the dismantling of the old political party network. Students, university professors, and journalists, bolstered by labor unions and inspired by a variety of democratic, socialist, communist, anarchist, and other thoughts, mounted large but orderly public demonstrations in favor of universal male suffrage in 1919 and 1920. The election of Katō Komei as Prime Minister of Japan continued democratic reforms that had been advocated by influential individuals on the left. This culminated in the passage of universal male suffrage in March 1925. This bill gave all male subjects over the age of 25 the right to vote, provided they had lived in their electoral districts for at least one year and were not homeless. The electorate thereby increased from 3.3 million to 12.5 million. In the political milieu of the day, there was a proliferation of new parties, including socialist and communist parties. Fear of a broader electorate, left-wing power, and the growing social change led to the passage of the Peace Preservation Law in 1925, which forbade any change in the political structure or the abolition of private property.

Unstable coalitions and divisiveness in the Diet led the Kenseikai (憲政会 Constitutional Government Association) and the Seiyū Hontō (政友本党 True Seiyūkai) to merge as the Rikken Minseitō (立憲民政党 Constitutional Democratic Party) in 1927. The Rikken Minseitō platform was committed to the parliamentary system, democratic politics, and world peace. Thereafter, until 1932, the Seiyūkai and the Rikken Minseitō alternated in power. Despite the political realignments and hope for more orderly government, domestic economic crises plagued whichever party held power. Fiscal austerity programs and appeals for public support of such conservative government policies as the Peace Preservation Law, including reminders of the moral obligation to make sacrifices for the emperor and the state, were attempted as solutions.

In 1932, Park Chun-kum was elected to the House of Representatives in the Japanese general election as the first person elected from a colonial background. In 1935, democracy was introduced in Farmosa/ Taiwan and in response to Taiwanese public opinion, local assemblies were established. In 1942, 38 colonial people were elected to local assemblies of the Japanese homeland. Overall, during the 1920s, Japan changed its direction toward a democratic system of government. However, parliamentary government was not rooted deeply enough to withstand the economic and political pressures of the 1930s, during which military leaders became increasingly influential. These shifts in power were made possible by the ambiguity and imprecision of the Meiji Constitution, particularly as regarded the position of the Emperor in relation to the constitution. Important institutional links existed between the party in government (Kōdōha) and military and political organizations, such as the Imperial Young Federation and the "Political Department" of the Kempeitai. Among the himitsu kessha (secret societies), the Kokuryu-kai and Kokka Shakai Shugi Gakumei (National Socialist League) also had close ties to the government. The Tonarigumi (residents committee) groups, the Nation Service Society (national government trade union), and Imperial Farmers Association were all allied as well. Other organizations and groups related with the government in wartime were the Double Leaf Society, Kokuhonsha, Taisei Yokusankai, Imperial Youth Corps, Keishichō, Shintoist Rites Research Council, Treaty Faction, Fleet Faction, and Volunteer Fighting Corps. Okawa Shumei and others began to write Coprospist political ideals and visions for Japanese future.

Sadao Araki was an important figurehead and founder of the Army party and the most important militarist thinker in his time. His first ideological works date from his leadership of the Kōdōha (Imperial Benevolent Rule or Action Group), opposed by the Tōseiha (Control Group) led by General Kazushige Ugaki. He linked the ancient (bushido code) and contemporary local and European fascist ideals (see Statism in Shōwa Japan), to form the ideological basis of the movement (Shōwa nationalism). From September 1931, the Japanese were becoming more locked into the course that would lead them into the Second World War, with Araki leading the way. Totalitarianism, militarism, and expansionism were to become the rule, with fewer voices able to speak against it. In a September 23 news conference, Araki first mentioned the philosophy of "Kōdōha" (The Imperial Way Faction). The concept of Kodo linked the Emperor, the people, land, and morality as indivisible. This led to the creation of a "new" Shinto and increased Emperor worship. Thanks to a coup d'état launched by the ultranationalist Kōdōha faction with the military, many politicians and military members of the former government died, giving rise to the Coprospist faction after the Emperor had interfered and stopped the coup. Kōdōha members were purged from the top military positions and the Tōseiha faction gained dominance for some time. However, both factions believed in expansionism, a strong military, and a coming war. Furthermore, Kōdōha members, while removed from the military, still had political influence within the government. Shortly after the Coprospists would outnumber and overpower both factions and become the main driving and political force in the Japanese Empire.

The state was being transformed to serve the Emperor and not only liberate all of Asia, but guide it under Japanese leadership. Symbolic katana swords came back into fashion as the martial embodiment of traditional beliefs, and the Nambu pistol became its contemporary equivalent, with the implicit message that the Army doctrine of close combat would prevail. The final objective, as envisioned by Army thinkers such as Sadao Araki and right-wing line followers, was a return to the old Shogunate system, but in the form of a contemporary Military Shogunate, resulting in a short return of the Shogunate during the End of the Second Great War in 1944. On the other hand, the traditionalist Coprospist militarists defended the Emperor and a constitutional monarchy with a significant religious aspect and would soon become the leading political force. A third point of view was supported by Prince Chichibu, a brother of Emperor Shōwa, who repeatedly counseled him to implement a direct imperial rule, even if that meant suspending the constitution. With the launching of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association in 1940 by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, Japan would turn to a form of government that resembled totalitarianism. This unique style of government, very similar to fascism, was known as Shōwaism outside of Japan or Hirohitoism inside of the Co-Prosperity Sphere . In the early twentieth century, a distinctive style of architecture was developed for the empire. The Coprospist later referred to it as Imperial Crown Style (帝冠様式, teikan yōshiki), that was originally referred to as Emperor's Crown Amalgamate Style, and sometimes Emperor's Crown Style (帝冠式, Teikanshiki). The style is identified by Japanese-style roofing on top of Neoclassical styled buildings; and can have a centrally elevated structure with a pyramidal dome. The prototype for this style was developed by architect Shimoda Kikutaro in his proposal for the Imperial Diet Building (present National Diet Building) in 1920, although his proposal was ultimately rejected. Outside of the Japanese mainland, in the rest of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, Imperial Crown Style architecture often included regional architectural elements.

At the same time, the zaibatsu trading groups (principally Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sumitomo, and Yasuda) looked towards great future expansion as well. Their main concern was a shortage of raw materials. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe combined social concerns with the needs of capital, and planned for expansion. The main goals of Japan's expansionism were acquisition and protection of spheres of influence, maintenance of territorial integrity, acquisition of raw materials, and access to Asian markets. Western nations, notably Great Britain, France, and the United States, had for long exhibited great interest in the commercial opportunities in China and other parts of Asia on exploit of Japanese regional interests. These opportunities had attracted Western investment because of the availability of raw materials for both domestic production and re-export to Asia. Japan desired these opportunities in planning the development of the Co-Prosperity Sphere under a Coprospist Ideology. The Great Depression, just as in many other countries, hindered Japan's economic growth. The Japanese Empire's main problem lay in that rapid industrial expansion had turned the country into a major manufacturing and industrial power that required raw materials; however, these had to be obtained from overseas, as there was a critical lack of natural resources on the home islands. Coprospist politicians, writers and ideological heads argued that all of this was a result of forceful opening of Japan to the Outside World by the Western Powers and then preventing Japan to gain the accesses to resources and markets it's people needed to survive, so these Western Powers could exploit the Japanese. In the 1920s and 1930s, Japan needed to import raw materials such as iron, rubber, and oil to maintain strong economic growth. Most of these resources came from the United States. The Japanese felt that acquiring resource-rich territories would establish economic self-sufficiency and independence, and they also hoped to jump-start the nation's economy in the midst of the depression.

As a result, Japan set its sights on East Asia, specifically Manchuria with its many resources; Japan needed these resources to continue its economic development and maintain national integrity. Shortly after invading Manchuria, the Japanese established the Empire of Manchukuo and “re-liberated” Korea to the Chosen Empire as well, tho depending puppet states and vasalls that then together formed the Co-Prosperity Sphere to pretend they were autonomous and independent, just like the British Dominions or the Russian Soviet Republics were. In Cahar the Japanese installed a pro-Japanese Mongol Political Committee, soon turning it into the Mengjiang Khanate in North Shanxi, South Cahar, Cahar and Xilinguole. Fights in Suiyuan and Shanxi ended, when local Warlord Yan Xishan made a deal with the Japanese North China Area Army, after some border clashes, seizing the opportunity to gain the now in a treaty demilitarized provinces of Hopeh/ Hebei, Shantung and Shanxi, while Mengjiang in return gained Bayantalam Wulanchabu and Yikezhao (Ordos) in the North from him in exchange. Declaring that his new state would be known as Yankoku (with the Jin Dialect as the main language) and in reference to a ancient Chinese State of the same name, as well as his own name, Father Yan/ Emperor Yan Xishan soon openly switched to the Japanese side, finally cementing their grip on Northern China and this time not stopped by outside interference of other Great Powers. The Co-Prosperity Sphere was bordn and Coprospism began to increase it's influence over Asia.