So this update might be a little ASB for many people, given how far ahead of OTL it is technologically. However, I hope that I've set out previous changes in TTL's engineering teaching and R&D that make it, broadly, plausible.

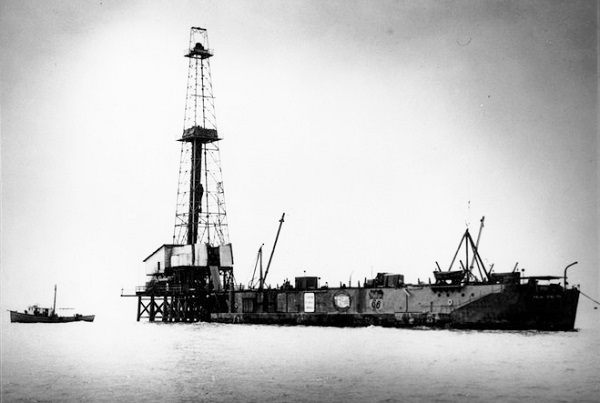

The Montrose Oil Drill - the first offshore rig to successfully draw oil out of sight of land

Since the beginning of its mission in 1926, the British Geological Survey’s search for oil fields in British territorial waters had pottered along with greater or lesser intensity but with nothing to show for it in terms of practical results. Those funny little men with their floating drills and fragile structures in the middle of the sea: to those who remembered their existence they were little more than a quaint monument to English eccentricity. However, that concealed a serious dedication to their task which put their research and engineering several decades ahead of their competitors, a dedication that would pay off dramatically in October 1946, with the discovery of the Montrose Oil Field about 135 miles east of Aberdeen, followed by the vast Forties and Brent Oil Fields in November and December. Using state of the art oil rigs and extraction technologies, the British government became, at a stroke, one of the most oil-rich entities in the world.

A connected, but not necessarily linked, event was the fate of Anglo-Arabian Petroleum, a company founded to prospect for oil in the Arabian Peninsula in 1933. Originally a private company with a mix of British and Arabian shareholders, the company’s shares were progressively taken over by the British and Arabian governments during the course of the World War such that, by 1945, it was effectively a joint-owned venture with the Arabian government.

These two phenomena transformed not only the UK’s energy picture, which until then had been reliant on increasingly inefficient domestic coal production and foreign oil imports, but also its trade balance, as oil revenues (even if they wouldn’t be fully realised until the 1950s) allowed industries to be repurposed from war and exports and towards domestic consumption. However, the promise of a rush of this ‘black gold’ immediately raised questions about what to do with it. The most obvious answer was to plunge this money into the social security programmes the government was trying to undertake, which was the argument made by many prominent people such as Ernest Bevin and Health Secretary Nye Bevan (not people who, otherwise, agreed on much). On the other hand, figures such as Herbert Morrison proposed creating a single nationalised oil and energy company which could be used as a job creator. Finally, Cripps and Keynes suggested the creation of an investment fund for the future.

Attlee, ever the conciliator in these things, contrived to produce a compromise which was amenable to all sides. An investment fund was set up with proceeds to be divided up three ways: the vast majority of profits would be paid directly back to the fund for reinvestment; profits above a certain level would be paid into a nationalised company with certain R&D directives; profits above that would be paid directly into the exchequer. The investment aims of what was named ‘The Sovereign Wealth Fund of the United Kingdom’ (or, more simply, the ‘SWF’) were kept deliberately vague, with the only limit being that whatever investments that were made be made ‘in the UK national interest.’ In practice, the founding charter of the SWF stipulated that the government would have input into what counted as the national interest, even though the SWF had considerable latitude in its investment decisions.

Keynes, who, despite a health scare in 1946 that some conspiracists claimed was a heart attack, remained vigorous, was tapped up to head the SWF. He agreed immediately and would chair the organisation from its formation on 1 January 1948. Under Keynes’ tenure, the value of the SWF grew every year at an astonishing rate, outperforming an average UK and Commonwealth equity index by an average of 12% a year, building up its equity and asset reserves substantially, all the while providing the extra funding for Labour’s ambitious domestic and foreign agenda. By the time of Keynes’ death (at his desk, fittingly enough) on 21 April 1956, the SWF was the largest and most influential investment fund in the world.

* * *

Black Gold: The Royal Geological Survey and the Saving of the British Economy

The Montrose Oil Drill - the first offshore rig to successfully draw oil out of sight of land

Since the beginning of its mission in 1926, the British Geological Survey’s search for oil fields in British territorial waters had pottered along with greater or lesser intensity but with nothing to show for it in terms of practical results. Those funny little men with their floating drills and fragile structures in the middle of the sea: to those who remembered their existence they were little more than a quaint monument to English eccentricity. However, that concealed a serious dedication to their task which put their research and engineering several decades ahead of their competitors, a dedication that would pay off dramatically in October 1946, with the discovery of the Montrose Oil Field about 135 miles east of Aberdeen, followed by the vast Forties and Brent Oil Fields in November and December. Using state of the art oil rigs and extraction technologies, the British government became, at a stroke, one of the most oil-rich entities in the world.

A connected, but not necessarily linked, event was the fate of Anglo-Arabian Petroleum, a company founded to prospect for oil in the Arabian Peninsula in 1933. Originally a private company with a mix of British and Arabian shareholders, the company’s shares were progressively taken over by the British and Arabian governments during the course of the World War such that, by 1945, it was effectively a joint-owned venture with the Arabian government.

These two phenomena transformed not only the UK’s energy picture, which until then had been reliant on increasingly inefficient domestic coal production and foreign oil imports, but also its trade balance, as oil revenues (even if they wouldn’t be fully realised until the 1950s) allowed industries to be repurposed from war and exports and towards domestic consumption. However, the promise of a rush of this ‘black gold’ immediately raised questions about what to do with it. The most obvious answer was to plunge this money into the social security programmes the government was trying to undertake, which was the argument made by many prominent people such as Ernest Bevin and Health Secretary Nye Bevan (not people who, otherwise, agreed on much). On the other hand, figures such as Herbert Morrison proposed creating a single nationalised oil and energy company which could be used as a job creator. Finally, Cripps and Keynes suggested the creation of an investment fund for the future.

Attlee, ever the conciliator in these things, contrived to produce a compromise which was amenable to all sides. An investment fund was set up with proceeds to be divided up three ways: the vast majority of profits would be paid directly back to the fund for reinvestment; profits above a certain level would be paid into a nationalised company with certain R&D directives; profits above that would be paid directly into the exchequer. The investment aims of what was named ‘The Sovereign Wealth Fund of the United Kingdom’ (or, more simply, the ‘SWF’) were kept deliberately vague, with the only limit being that whatever investments that were made be made ‘in the UK national interest.’ In practice, the founding charter of the SWF stipulated that the government would have input into what counted as the national interest, even though the SWF had considerable latitude in its investment decisions.

Keynes, who, despite a health scare in 1946 that some conspiracists claimed was a heart attack, remained vigorous, was tapped up to head the SWF. He agreed immediately and would chair the organisation from its formation on 1 January 1948. Under Keynes’ tenure, the value of the SWF grew every year at an astonishing rate, outperforming an average UK and Commonwealth equity index by an average of 12% a year, building up its equity and asset reserves substantially, all the while providing the extra funding for Labour’s ambitious domestic and foreign agenda. By the time of Keynes’ death (at his desk, fittingly enough) on 21 April 1956, the SWF was the largest and most influential investment fund in the world.

Last edited: