No, West Prussia was the area annexed from Poland in the First Partition. Brandenburg is the March of Brandenburg, which was southwest of West Prussia.So what became known as West Prussia actually was mainly the old Brandenburg

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Anglo-Saxon Social Model

- Thread starter Rattigan

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Eastern European Colonisation, 1945-55

A shorter update on Eastern Europe. Not much is different from OTL (hence why I want to run these all out this week to stop spending too much time on it) but there are a couple of under-the-surface changes which I (at least) think are significant and a few relevant impacts on the Commonwealth intellectual and leftist classes that I thought worth mentioning. As with yesterday, profuse apologies for the lack of maps: I'm currently snowed under with marking/grading/graduation but will hopefully have more time to learn a new skill over the summer (some people learn a new language, I do this...). As some of you might have noticed, I've changed the names of East Prussia and West Prussia mentioned yesterday to 'Prussia' and 'Brandenburg,' respectively.

As ever, all feedback/praise/abuse welcome and I'll try and answer as best I can.

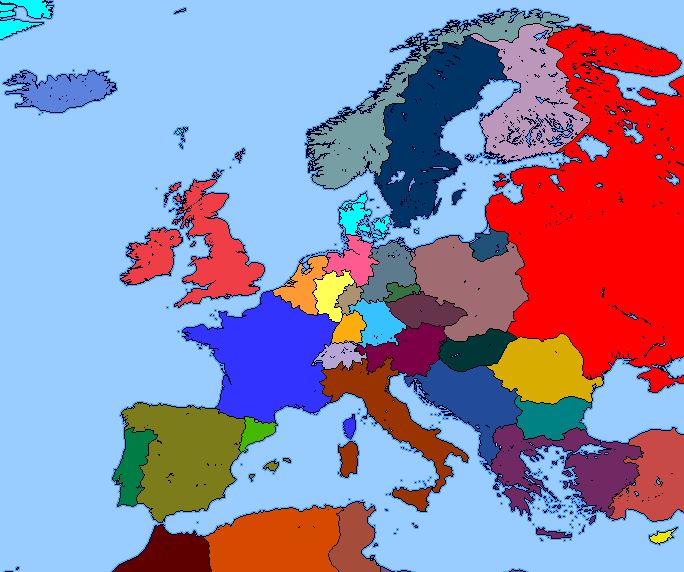

[EDIT] I've now got a map of Europe which I've put with the update for western Europe.

The Red Man's Burden: Communism and Empire in Eastern Europe

The Red King: King Mihai I of Romania in 1947

During the course of the World War, the Soviet Union had conclusively attained the level of a global superpower: the Red Army was the largest the world had ever known (and arguably the mightiest), its heavy industry was vast and its resources near-unparallelled. But, at the same time, the Soviet government was nothing if not paranoid and the lasting legacy of the failed Soviet-German Pact of 1939-41 was to reinforce the belief that the capitalist world would stop at nothing to overthrow them.

Fighting the German invasion had inflicted profound political changes on the Soviet system. The capture of Petrograd in September and the flight of the Soviet bureaucracy to Moscow had finally caused the one thing that had concerned those at the top of the Soviet government since Lenin suffered the first of his strokes in 1922: namely, the fall of civilian government and the emergence of a Bonaparte. This time, the man the took the reigns was Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a career soldier who, despite his family’s aristocratic origins, had joined the Bolsheviks in 1917 and worked his way up the ranks over the course of the 1920s before being put in command of the military reforms of the 1930s. Managing to avoid blame for the poor state of Soviet border defences in 1941, in October 1941 Tukhachevsky had organised enough political allies to install himself as the Soviet Premier. However, with Nikolay Krestinsky remaining as General Secretary and Bukharin in the Finance Ministry, there was sufficient continuity in domestic affairs to keep the rest of the Soviet political class more or less on-side with this semi-coup.

In the postwar years, Tukhachevsky set out with the explicit aim of building up a network of client states who would serve as a buffer zone in Europe. As we have already seen, the early parts of that were accomplished over the course of 1944-49 with Anglo-American connivance, resulting in the creation of communist dictatorships in Poland, Saxony, West Prussia, East Prussia and (later) Czechia. But Soviet ambitions, as it had done so for their Tsarist predecessors, also focused on the Balkans and Central Asia. In secret negotiations at the Potsdam Conference, Churchill and Roosevelt privately agreed that the Soviets should be allowed a free hand in the region.

Bulgaria fell swiftly, with the royal family having been expelled in a communist-backed coup in 1944 and a republican constitution being rubber stamped by a referendum in February 1946, at the same time as the Bulgarian Communist Party won 75% of the seats in a rigged election to the new constituent assembly. Over the course of the rest of the 1940s, the BCP would coerce smaller parties into joining them and intimidate those who refused, until elections in 1950 gave the BCP-dominated Fatherland Front 100% of the seats. Hungary suffered the same fate: conquered by the Red Army in February 1945, a communist regime was installed under Matyas Rakosi in November 1945 with little pretence of democratic accountability.

Romania was slightly different, something conditioned by its unusual history during the interwar and war years. Over the course of the 1920s, Romania and the Soviet Union had grown closer to each other, with both countries recognising that their energy resources made cooperation useful. The first attempt to weaponise that cooperation, the February 1941 oil embargo on Germany, however, ended disastrously for both countries, with Romania occupied and the Soviet Union ravaged by Operation Typhoon. Nevertheless, friendly relations did give the Romanian government and royal family a place to flee to and from which they could organise resistance movements and, finally, a return to power on the backs of a Soviet invasion and a popular uprising in August 1944.

In the immediate postwar years, Romania was granted a lot more political freedom than Bulgaria, Poland or the dismembered Germany. Partly this was because of the historic good relations between the two countries but it was also because both King Michael and his prime minister Constantin Stanescu were reliably loyal to Petrograd, despite their aristocratic and small-’c’ conservative lineages. Their governing programme included land reform and the Romanian Communist Party was already strong, especially compared to the situation in Bulgaria or the German countries in 1945. The Communist Party won more seats than any other in the free elections of May 1946, becoming the largest party in a coalition made up of six parties and headed by Stanescu.

However, the Soviets thereafter grew frustrated with the Communists’ failure of make a significant gains in the elections of February 1948. Thereafter, Soviet and Romanian Communist Parties began to formulate plans for a coup. In July 1948, pro-Communist military units and protestors surrounded the Royal Palace and demanded that Michael dismiss his government and replace it with one entirely made up of Communist ministers. Fearful of civil war and a Soviet invasion if he did not comply, Michael capitulated to their demands and an entirely Communist government under Petru Groza was appointed. In elections held in November 1948, a single list of candidates from the National Front (as the expanded Communist Party was renamed) was elected to the Parliament in rigged elections. Michael himself staggered on until a secret agreement in April 1949 allowed him to flee with his family in a Royal Naval ship and a republican constitution was instituted in his absence.

Leon Trotsky (who, since being forced out of the Foreign Ministry once more in 1926, had been sidelined in a variety of undistinguished academic and bureaucratic offices) wrote an article in ‘Pravda’ in August 1950 arguing that this was the culmination of his revolutionary vision in 1919. But few, at least not in the Tauride Palace, were fooled: this was imperialism, red in tooth and claw. While most bureaucrats probably did believe that these countries would be better served as Soviet satellites than they would if left free to toss and turn on the waves of the free market (where they would probably become satellites of the British or the Americans anyway), there was little pretence that they had joined a willing association with the USSR or that they retained popular legitimacy. Over the course of the 1950s, elections were cancelled and legislative assemblies abolished in favour of appointed 'revolutionary councils' of one flavour or another. These councils often included Soviet bureaucrats and military officers as ‘advisers,’ an idea borrowed from the British method of governing the Indian Princely States.

The final countries in eastern Europe were Serbia and Greece, both of whom had been fighting guerilla wars against Italo-Bulgarian occupation during the World War. Unlike the other countries in the region, the Ally with the biggest presence in these countries by the end of 1945 was Britain. At their meeting in Potsdam, Tukhachevsky had acknowledged British interests in the region and therefore did not give support to the Communist insurgents in the country. Although Britain desired the reinstallation of the Serbian and Greek monarchs as a bulwark against them being drawn into the Soviet camp, they had no interest in attempting to impose a repressive, conservative regime on either of those countries (partly for moral reasons, partly for financial ones).

To that end, the British made a requirement of their support for the monarchies that both would bring democratic socialists into government. Of the two monarchies, the Serbian one was slightly more positive about this requirement, Peter II being ambivalent about politics in general and preferring the idea of constitutional monarchy to save himself from the boring duties of governing. To this end, Serbia[1] was reconstituted in 1946 as a constitutional monarchy called the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, with prominent former communist partisans Milan Dilas, Aleksandar Rankovic, Boris Kidric and Svetozar Vukmanovic in the cabinet as part of a coalition. Greece took a bit longer but a constitutional Kingdom of Greece[2] eventually emerged in October 1948 with a coalition government lead by the social democrat Georgios Papandreou and the moderate communist Markos Vafiadis.

The takeover of eastern Europe proved to be a watershed moment in the history of global communism, with notable effects in the Commonwealth. Communism, it turned out, was no bulwark against oppression and imperialism. For example, in Australia it is credited with the collapse of communist influence within the trades union movement, which some have argued preserved the unity of the Australian Labour Party. In the UK, too, these events set off dramatic changes in the intellectual class. Christopher Hill and E.P. Thompson were amongst the figures who left the party in the late 1940s and would go on to have careers as public intellectuals. Their journal ‘Past & Present,’ founded in 1952, would take a left wing but avowedly non-communist position, further pushing the British left in that general direction.

[1] OTL Serbia, Kosovo, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia

[2] OTL Greece, FYR Macedonia and Istanbul, West Marmara, Aegean and East Marmara regions

As ever, all feedback/praise/abuse welcome and I'll try and answer as best I can.

[EDIT] I've now got a map of Europe which I've put with the update for western Europe.

* * *

The Red Man's Burden: Communism and Empire in Eastern Europe

The Red King: King Mihai I of Romania in 1947

During the course of the World War, the Soviet Union had conclusively attained the level of a global superpower: the Red Army was the largest the world had ever known (and arguably the mightiest), its heavy industry was vast and its resources near-unparallelled. But, at the same time, the Soviet government was nothing if not paranoid and the lasting legacy of the failed Soviet-German Pact of 1939-41 was to reinforce the belief that the capitalist world would stop at nothing to overthrow them.

Fighting the German invasion had inflicted profound political changes on the Soviet system. The capture of Petrograd in September and the flight of the Soviet bureaucracy to Moscow had finally caused the one thing that had concerned those at the top of the Soviet government since Lenin suffered the first of his strokes in 1922: namely, the fall of civilian government and the emergence of a Bonaparte. This time, the man the took the reigns was Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a career soldier who, despite his family’s aristocratic origins, had joined the Bolsheviks in 1917 and worked his way up the ranks over the course of the 1920s before being put in command of the military reforms of the 1930s. Managing to avoid blame for the poor state of Soviet border defences in 1941, in October 1941 Tukhachevsky had organised enough political allies to install himself as the Soviet Premier. However, with Nikolay Krestinsky remaining as General Secretary and Bukharin in the Finance Ministry, there was sufficient continuity in domestic affairs to keep the rest of the Soviet political class more or less on-side with this semi-coup.

In the postwar years, Tukhachevsky set out with the explicit aim of building up a network of client states who would serve as a buffer zone in Europe. As we have already seen, the early parts of that were accomplished over the course of 1944-49 with Anglo-American connivance, resulting in the creation of communist dictatorships in Poland, Saxony, West Prussia, East Prussia and (later) Czechia. But Soviet ambitions, as it had done so for their Tsarist predecessors, also focused on the Balkans and Central Asia. In secret negotiations at the Potsdam Conference, Churchill and Roosevelt privately agreed that the Soviets should be allowed a free hand in the region.

Bulgaria fell swiftly, with the royal family having been expelled in a communist-backed coup in 1944 and a republican constitution being rubber stamped by a referendum in February 1946, at the same time as the Bulgarian Communist Party won 75% of the seats in a rigged election to the new constituent assembly. Over the course of the rest of the 1940s, the BCP would coerce smaller parties into joining them and intimidate those who refused, until elections in 1950 gave the BCP-dominated Fatherland Front 100% of the seats. Hungary suffered the same fate: conquered by the Red Army in February 1945, a communist regime was installed under Matyas Rakosi in November 1945 with little pretence of democratic accountability.

Romania was slightly different, something conditioned by its unusual history during the interwar and war years. Over the course of the 1920s, Romania and the Soviet Union had grown closer to each other, with both countries recognising that their energy resources made cooperation useful. The first attempt to weaponise that cooperation, the February 1941 oil embargo on Germany, however, ended disastrously for both countries, with Romania occupied and the Soviet Union ravaged by Operation Typhoon. Nevertheless, friendly relations did give the Romanian government and royal family a place to flee to and from which they could organise resistance movements and, finally, a return to power on the backs of a Soviet invasion and a popular uprising in August 1944.

In the immediate postwar years, Romania was granted a lot more political freedom than Bulgaria, Poland or the dismembered Germany. Partly this was because of the historic good relations between the two countries but it was also because both King Michael and his prime minister Constantin Stanescu were reliably loyal to Petrograd, despite their aristocratic and small-’c’ conservative lineages. Their governing programme included land reform and the Romanian Communist Party was already strong, especially compared to the situation in Bulgaria or the German countries in 1945. The Communist Party won more seats than any other in the free elections of May 1946, becoming the largest party in a coalition made up of six parties and headed by Stanescu.

However, the Soviets thereafter grew frustrated with the Communists’ failure of make a significant gains in the elections of February 1948. Thereafter, Soviet and Romanian Communist Parties began to formulate plans for a coup. In July 1948, pro-Communist military units and protestors surrounded the Royal Palace and demanded that Michael dismiss his government and replace it with one entirely made up of Communist ministers. Fearful of civil war and a Soviet invasion if he did not comply, Michael capitulated to their demands and an entirely Communist government under Petru Groza was appointed. In elections held in November 1948, a single list of candidates from the National Front (as the expanded Communist Party was renamed) was elected to the Parliament in rigged elections. Michael himself staggered on until a secret agreement in April 1949 allowed him to flee with his family in a Royal Naval ship and a republican constitution was instituted in his absence.

Leon Trotsky (who, since being forced out of the Foreign Ministry once more in 1926, had been sidelined in a variety of undistinguished academic and bureaucratic offices) wrote an article in ‘Pravda’ in August 1950 arguing that this was the culmination of his revolutionary vision in 1919. But few, at least not in the Tauride Palace, were fooled: this was imperialism, red in tooth and claw. While most bureaucrats probably did believe that these countries would be better served as Soviet satellites than they would if left free to toss and turn on the waves of the free market (where they would probably become satellites of the British or the Americans anyway), there was little pretence that they had joined a willing association with the USSR or that they retained popular legitimacy. Over the course of the 1950s, elections were cancelled and legislative assemblies abolished in favour of appointed 'revolutionary councils' of one flavour or another. These councils often included Soviet bureaucrats and military officers as ‘advisers,’ an idea borrowed from the British method of governing the Indian Princely States.

The final countries in eastern Europe were Serbia and Greece, both of whom had been fighting guerilla wars against Italo-Bulgarian occupation during the World War. Unlike the other countries in the region, the Ally with the biggest presence in these countries by the end of 1945 was Britain. At their meeting in Potsdam, Tukhachevsky had acknowledged British interests in the region and therefore did not give support to the Communist insurgents in the country. Although Britain desired the reinstallation of the Serbian and Greek monarchs as a bulwark against them being drawn into the Soviet camp, they had no interest in attempting to impose a repressive, conservative regime on either of those countries (partly for moral reasons, partly for financial ones).

To that end, the British made a requirement of their support for the monarchies that both would bring democratic socialists into government. Of the two monarchies, the Serbian one was slightly more positive about this requirement, Peter II being ambivalent about politics in general and preferring the idea of constitutional monarchy to save himself from the boring duties of governing. To this end, Serbia[1] was reconstituted in 1946 as a constitutional monarchy called the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, with prominent former communist partisans Milan Dilas, Aleksandar Rankovic, Boris Kidric and Svetozar Vukmanovic in the cabinet as part of a coalition. Greece took a bit longer but a constitutional Kingdom of Greece[2] eventually emerged in October 1948 with a coalition government lead by the social democrat Georgios Papandreou and the moderate communist Markos Vafiadis.

The takeover of eastern Europe proved to be a watershed moment in the history of global communism, with notable effects in the Commonwealth. Communism, it turned out, was no bulwark against oppression and imperialism. For example, in Australia it is credited with the collapse of communist influence within the trades union movement, which some have argued preserved the unity of the Australian Labour Party. In the UK, too, these events set off dramatic changes in the intellectual class. Christopher Hill and E.P. Thompson were amongst the figures who left the party in the late 1940s and would go on to have careers as public intellectuals. Their journal ‘Past & Present,’ founded in 1952, would take a left wing but avowedly non-communist position, further pushing the British left in that general direction.

[1] OTL Serbia, Kosovo, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia

[2] OTL Greece, FYR Macedonia and Istanbul, West Marmara, Aegean and East Marmara regions

Last edited:

Western Europe, 1945-54

A Continent Safe for Capitalism: NATO, the World Bank and the Anglo-American Empire in Europe, 1945-54

The King of the Benelux: General Bernard Freyburg greets dignitaries are part of his role commanding the Commonwealth occupation of the Low Countries

While the Soviet domination of eastern Europe was very traditional in what its projection of hegemonic power looked like, the same could not be said for the supposed ‘Anglo-American sphere’ in western and southern Europe. Rather than seeking a traditional military domination, the Commonwealth and the Americans sought to build stable market democracies in those countries, who would then be reliable trading allies for the UK and the USA. In the words of the historian Adam Tooze, the plan was to “make the continent safe for capitalism and democracy.” The fact that this happened in such a relatively smooth manner often makes one forget that it was in fact a notable achievement, capitalism and mass democracy having previously not been regarded as natural bedfellows.

Saying that the Anglo-American alliance dominated southern and western Europe obscures that they were in fact dealing with at least four fundamentally different types of polities. In the first place, were the utterly defeated enemy combatants (Spain and the western German territories), who could be disposed of pretty much as the victors wished. Secondly, there was Italy who, although an unconditionally surrendered opponent, had only been occupied (outside of Sicily and its overseas colonies) after its surrender and whose material and economic infrastructure remained largely intact. Thirdly, there were the Benelux countries: technically victors (some with continuing imperial pretensions) but economically and materially seemingly as ruined as much as Germany. Finally, there was the special case of France: a country which seemed in a similar position to the Benelux but who in practice had valid great power pretensions and a vibrant and independent-minded political culture of its own.

As we have already seen, to deal with Germany the Allies simply abolished her as a nation and partitioned her up as best fitted their needs. Although they did not partition her nor abolish her legal personality, something very similar did happen to Spain. Following the defeat of the Falangist government in March 1943, a provisional government had been formed under the nominal leadership of General Francisco Franco, but in truth all power was held by the Commonwealth military authorities. In February 1946, Franco was unceremoniously defenestrated when it became clear that he would resist any attempts to install a democracy. Instead, a constitution was imposed with a parliamentary system based on the Westminster system and a ceremonial head of state elected by the legislative assembly. Miguel Maura’s Liberal Republican Party won the first elections in May 1947, defeating the Republican Left Party of Diego Martinez Barrio.

The territorial changes to Italy, too, were moderate, with her colonies being confiscated (Libya to become an independent kingdom, Albania to Yugoslavia and Somaliland and Eritrea absorbed into Ethiopia) and Istria being divided between Austria and Yugoslavia.[1] Perhaps surprisingly, the occupying American forces alighted on the exiled former monarchy as a way of securing a reasonably consensual head of state. Victor Emmanuel himself was judged to be too controversial, given his role in the collapse of the first Kingdom in the 1930s. But his son could be prevailed upon to accept a constitutional system and rule as Umberto II. A new constitution was drafted which required political parties to adhere to the democratic basis of the state (under penalty of being abolished by the constitutional court), an implicit threat to the Communist Party. Furthermore, although the legislative chamber retained a level of proportional representation, parties were required to achieve a minimum percentage of the popular vote (set at 5%) before they could send delegates. The new constitution and the return of the monarchy were put to a referendum in June 1946, followed by the first elections to the assembly three months later. The newly-constituted Christian Democrat Party, a coalition of various centrist and centre-right movements, won the majority and formed a government under Alcide De Gasperi. The Communist Party came in second, its commitment to the democratic process proved, something which was cemented by the party’s formal break from the Soviet Union (over its anti-democratic conquest of eastern Europe) in 1949. This comparative stability, combined with the country itself being relatively untouched by the War, laid the grounds for the Italian economic miracle of the 1950s and ‘60s.

France was a unique case, with Charles De Gaulle anxious that she should retain her independence outside of the Anglo-American orbit. He thus insisted that France have her own area of occupation in Germany, a permanent seat on the security council and undertook several measures to re-secure her colonial empire after 1945. Although French politics was thrown into chaos by the assassination of De Gaulle in 1946, of which more will be spoken of later, France remained very jealous of her independence from the British and the Americans, something which was key to President Bonnet’s decision to veto the French joining of NATO in 1949 (although she would join in 1952 under President Leclerc). When the French Union was formally constituted in 1958, it was regarded as a big failure of Anglo-American diplomacy in Westminster and Washington foreign policy circles.

In the Low Countries, any pretensions local elites had of a return to the status quo 1939 was swiftly disabused when the Belgian King, Leopold III, was told in no uncertain terms by the head of the Commonwealth occupation forces, General Bernard Freyberg, that, in view of his collaboration with occupying German forces in 1940-45, it would no longer be appropriate for him to carry on his royal duties. 15-year-old Crown Prince Baudouin was installed in his place and Leopold spent the rest of his life in a luxurious form of house arrest in the Chateau des Amerois (his guards were always Commonwealth soldiers) until his death in 1983. Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg, both of whom were judged by the British to have had a ‘good war,’ were allowed to keep their thrones. But beyond that there was little need to make radical changes to their political structures, those three countries having had relatively stable democracies in the first place. They did, however, desperately need money to re-start their economies and all three became the first recipients of WBG grants in August 1948.

Commonwealth soldiers would remain in those three countries for many years, with Freyburg gaining the nickname ‘the King of the Benelux.’ He used his influence to encourage closer cooperation between the three nations, as well as to urge the Netherlands to stay in the fight when a communist rebellion broke out in the Dutch East Indies in 1949. The creation of the Benelux Union in 1954, a political and economic confederation of the three nations, was regarded as one of his major successes.

As mentioned already, the overarching framework of the Anglo-American relationship took the form of the NATO military alliance. This served Commonwealth purposes well by tying the Americans, now militarily as well as economically, to the fate of Europe. The equal involvement of the three superpowers would, it was hoped in Westminster, preserve the European balance of power. At its inception its members were:

[1] TTL Italy shares OTL borders minus South Tyrol and Friuli Venezia Giulia

Europe in c.1955

The King of the Benelux: General Bernard Freyburg greets dignitaries are part of his role commanding the Commonwealth occupation of the Low Countries

While the Soviet domination of eastern Europe was very traditional in what its projection of hegemonic power looked like, the same could not be said for the supposed ‘Anglo-American sphere’ in western and southern Europe. Rather than seeking a traditional military domination, the Commonwealth and the Americans sought to build stable market democracies in those countries, who would then be reliable trading allies for the UK and the USA. In the words of the historian Adam Tooze, the plan was to “make the continent safe for capitalism and democracy.” The fact that this happened in such a relatively smooth manner often makes one forget that it was in fact a notable achievement, capitalism and mass democracy having previously not been regarded as natural bedfellows.

Saying that the Anglo-American alliance dominated southern and western Europe obscures that they were in fact dealing with at least four fundamentally different types of polities. In the first place, were the utterly defeated enemy combatants (Spain and the western German territories), who could be disposed of pretty much as the victors wished. Secondly, there was Italy who, although an unconditionally surrendered opponent, had only been occupied (outside of Sicily and its overseas colonies) after its surrender and whose material and economic infrastructure remained largely intact. Thirdly, there were the Benelux countries: technically victors (some with continuing imperial pretensions) but economically and materially seemingly as ruined as much as Germany. Finally, there was the special case of France: a country which seemed in a similar position to the Benelux but who in practice had valid great power pretensions and a vibrant and independent-minded political culture of its own.

As we have already seen, to deal with Germany the Allies simply abolished her as a nation and partitioned her up as best fitted their needs. Although they did not partition her nor abolish her legal personality, something very similar did happen to Spain. Following the defeat of the Falangist government in March 1943, a provisional government had been formed under the nominal leadership of General Francisco Franco, but in truth all power was held by the Commonwealth military authorities. In February 1946, Franco was unceremoniously defenestrated when it became clear that he would resist any attempts to install a democracy. Instead, a constitution was imposed with a parliamentary system based on the Westminster system and a ceremonial head of state elected by the legislative assembly. Miguel Maura’s Liberal Republican Party won the first elections in May 1947, defeating the Republican Left Party of Diego Martinez Barrio.

The territorial changes to Italy, too, were moderate, with her colonies being confiscated (Libya to become an independent kingdom, Albania to Yugoslavia and Somaliland and Eritrea absorbed into Ethiopia) and Istria being divided between Austria and Yugoslavia.[1] Perhaps surprisingly, the occupying American forces alighted on the exiled former monarchy as a way of securing a reasonably consensual head of state. Victor Emmanuel himself was judged to be too controversial, given his role in the collapse of the first Kingdom in the 1930s. But his son could be prevailed upon to accept a constitutional system and rule as Umberto II. A new constitution was drafted which required political parties to adhere to the democratic basis of the state (under penalty of being abolished by the constitutional court), an implicit threat to the Communist Party. Furthermore, although the legislative chamber retained a level of proportional representation, parties were required to achieve a minimum percentage of the popular vote (set at 5%) before they could send delegates. The new constitution and the return of the monarchy were put to a referendum in June 1946, followed by the first elections to the assembly three months later. The newly-constituted Christian Democrat Party, a coalition of various centrist and centre-right movements, won the majority and formed a government under Alcide De Gasperi. The Communist Party came in second, its commitment to the democratic process proved, something which was cemented by the party’s formal break from the Soviet Union (over its anti-democratic conquest of eastern Europe) in 1949. This comparative stability, combined with the country itself being relatively untouched by the War, laid the grounds for the Italian economic miracle of the 1950s and ‘60s.

France was a unique case, with Charles De Gaulle anxious that she should retain her independence outside of the Anglo-American orbit. He thus insisted that France have her own area of occupation in Germany, a permanent seat on the security council and undertook several measures to re-secure her colonial empire after 1945. Although French politics was thrown into chaos by the assassination of De Gaulle in 1946, of which more will be spoken of later, France remained very jealous of her independence from the British and the Americans, something which was key to President Bonnet’s decision to veto the French joining of NATO in 1949 (although she would join in 1952 under President Leclerc). When the French Union was formally constituted in 1958, it was regarded as a big failure of Anglo-American diplomacy in Westminster and Washington foreign policy circles.

In the Low Countries, any pretensions local elites had of a return to the status quo 1939 was swiftly disabused when the Belgian King, Leopold III, was told in no uncertain terms by the head of the Commonwealth occupation forces, General Bernard Freyberg, that, in view of his collaboration with occupying German forces in 1940-45, it would no longer be appropriate for him to carry on his royal duties. 15-year-old Crown Prince Baudouin was installed in his place and Leopold spent the rest of his life in a luxurious form of house arrest in the Chateau des Amerois (his guards were always Commonwealth soldiers) until his death in 1983. Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg, both of whom were judged by the British to have had a ‘good war,’ were allowed to keep their thrones. But beyond that there was little need to make radical changes to their political structures, those three countries having had relatively stable democracies in the first place. They did, however, desperately need money to re-start their economies and all three became the first recipients of WBG grants in August 1948.

Commonwealth soldiers would remain in those three countries for many years, with Freyburg gaining the nickname ‘the King of the Benelux.’ He used his influence to encourage closer cooperation between the three nations, as well as to urge the Netherlands to stay in the fight when a communist rebellion broke out in the Dutch East Indies in 1949. The creation of the Benelux Union in 1954, a political and economic confederation of the three nations, was regarded as one of his major successes.

As mentioned already, the overarching framework of the Anglo-American relationship took the form of the NATO military alliance. This served Commonwealth purposes well by tying the Americans, now militarily as well as economically, to the fate of Europe. The equal involvement of the three superpowers would, it was hoped in Westminster, preserve the European balance of power. At its inception its members were:

- Baden-Wurttemberg

- Bavaria

- Belgium

- the Commonwealth

- Greece

- Hanover

- Hesse

- Italy

- Luxembourg

- Netherlands

- Rhineland

- Spain

- the United States

- Yugoslavia

[1] TTL Italy shares OTL borders minus South Tyrol and Friuli Venezia Giulia

Europe in c.1955

Last edited:

Middle East Partition, 1945-49

This is the final update in our miniseries about reconstruction, this time focusing on the Middle East. This is another update where lots of you will (rightly) complain about the lack of maps, for which I can only apologise and promise that it will be fixed one day...

[EDIT] A map is now attached.

From next week we'll be returning to the usual format of three updates a week. Next time will focus on Attlee's second term domestically, what happened to China and Indian developments.

The new face of Turkey: Nuri Demirag (seated, second from right) and other members of the Turkish delegation before the signing of the Ankara Accords in 1949

Turkey had entered the war as a rebuke to the Entente of the Great War, in particular the British. By joining the Axis, they hoped to reabsorb the lost territories of Armenia and Smyrna (the status of Constantinople in any putative Axis victory remains unclear: Italy promised it to Bulgaria but Germany implied that it would be returned to Turkey) and gain a share of the conquered territories in the Caucuses. They also believed that large portions of Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine would be returned to them from a defeated Britain, somewhat underestimating the de facto independence of Arabia by that point. While their armies had performed creditably in the Caucuses (in pure tactical terms), rumours of massacres of ethnic Armenian and Georgian civilians by occupying forces severely damaged Turkey’s reputation in 1945. When the Anglo-Arabian armies occupied Ankara and extracted an unconditional surrender from the government, the decision was taken to finally dismember the country.

The first such dismemberment was the handing over of the entire former international zone of Marmara to Greece, along with an enlarged Aegean region. It was an unwieldy conglomeration that left the new Greece with a substantial Muslim minority but it was nonetheless one that Tukhachevsky had agreed to in 1945 on the condition that the Red Fleet be granted free access to the straits of Constantinople (a grant made by the Commonwealth, of course: the Greeks didn’t have a say in this). One of the British aims through the foundation of NATO was - along with, in the language of the time, keeping ‘the Germans down, the Russians out and the Americans in’ - was to safeguard her own continuing control of the trade routes through the Mediterranean and, when the organisation was founded in 1949, Greece furthered that aim by being a member and a reliable Commonwealth ally.

With the Western Allies having already gobbled up one successor state, the Soviets wasted no time in securing another one for themselves. The new and expanded Republic of Armenia[1] was declared in the area occupied by the Soviet army over the summer of 1945. In Armenia, the occupying Soviets did not bother with the democratic niceties they had occasionally attempted in eastern Europe. Instead, a communist government was installed and a dictatorship established under Anastas Mikoyan without the prelude of ‘democratic’ elections.

The final country looking for a client/buffer state was Arabia who, although still de jure a British client, was de facto independent and sought to crush her former Turkish overlords once and for all. Indeed, with Arabia having suffered 298,000 casualties (89,000 in the Great War and 209,000 in the World War) fighting the Turks, the Big Five didn’t really think they could deny them that. To that end, the Republic of Kurdistan[2] was declared in February 1946.

This left the remainder of rump Turkey[3], effectively reduced to a square of central Anatolia. In 1949, the new Turkish President Nuri Demirag signed the Ankara Accords with representatives from Greece, Georgia, Kurdistan, Araba, NATO and the USSR. The Ankara Accords provided for the Turkish military to adopt a permanent declaration of neutrality, insert a number of pacifist amendments into their constitution and agree to never join a military alliance such as NATO or the Bucharest Pact.

[1] OTL Armenia and the Northeast Anatolia, Central East Anatolia and East Black Sea Regions

[2] OTL Southeast Anatolia Region

[3] OTL Mediterranean, Central Anatolia, West Black Sea and West Anatolia Regions

The Middle East following the signing of the Ankara Accords in 1949

[EDIT] A map is now attached.

From next week we'll be returning to the usual format of three updates a week. Next time will focus on Attlee's second term domestically, what happened to China and Indian developments.

* * *

Twilight of the Ottomans: The Partition of the Middle East, 1945-49

The new face of Turkey: Nuri Demirag (seated, second from right) and other members of the Turkish delegation before the signing of the Ankara Accords in 1949

Turkey had entered the war as a rebuke to the Entente of the Great War, in particular the British. By joining the Axis, they hoped to reabsorb the lost territories of Armenia and Smyrna (the status of Constantinople in any putative Axis victory remains unclear: Italy promised it to Bulgaria but Germany implied that it would be returned to Turkey) and gain a share of the conquered territories in the Caucuses. They also believed that large portions of Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine would be returned to them from a defeated Britain, somewhat underestimating the de facto independence of Arabia by that point. While their armies had performed creditably in the Caucuses (in pure tactical terms), rumours of massacres of ethnic Armenian and Georgian civilians by occupying forces severely damaged Turkey’s reputation in 1945. When the Anglo-Arabian armies occupied Ankara and extracted an unconditional surrender from the government, the decision was taken to finally dismember the country.

The first such dismemberment was the handing over of the entire former international zone of Marmara to Greece, along with an enlarged Aegean region. It was an unwieldy conglomeration that left the new Greece with a substantial Muslim minority but it was nonetheless one that Tukhachevsky had agreed to in 1945 on the condition that the Red Fleet be granted free access to the straits of Constantinople (a grant made by the Commonwealth, of course: the Greeks didn’t have a say in this). One of the British aims through the foundation of NATO was - along with, in the language of the time, keeping ‘the Germans down, the Russians out and the Americans in’ - was to safeguard her own continuing control of the trade routes through the Mediterranean and, when the organisation was founded in 1949, Greece furthered that aim by being a member and a reliable Commonwealth ally.

With the Western Allies having already gobbled up one successor state, the Soviets wasted no time in securing another one for themselves. The new and expanded Republic of Armenia[1] was declared in the area occupied by the Soviet army over the summer of 1945. In Armenia, the occupying Soviets did not bother with the democratic niceties they had occasionally attempted in eastern Europe. Instead, a communist government was installed and a dictatorship established under Anastas Mikoyan without the prelude of ‘democratic’ elections.

The final country looking for a client/buffer state was Arabia who, although still de jure a British client, was de facto independent and sought to crush her former Turkish overlords once and for all. Indeed, with Arabia having suffered 298,000 casualties (89,000 in the Great War and 209,000 in the World War) fighting the Turks, the Big Five didn’t really think they could deny them that. To that end, the Republic of Kurdistan[2] was declared in February 1946.

This left the remainder of rump Turkey[3], effectively reduced to a square of central Anatolia. In 1949, the new Turkish President Nuri Demirag signed the Ankara Accords with representatives from Greece, Georgia, Kurdistan, Araba, NATO and the USSR. The Ankara Accords provided for the Turkish military to adopt a permanent declaration of neutrality, insert a number of pacifist amendments into their constitution and agree to never join a military alliance such as NATO or the Bucharest Pact.

[1] OTL Armenia and the Northeast Anatolia, Central East Anatolia and East Black Sea Regions

[2] OTL Southeast Anatolia Region

[3] OTL Mediterranean, Central Anatolia, West Black Sea and West Anatolia Regions

The Middle East following the signing of the Ankara Accords in 1949

Last edited:

Thomas Wilkins

Banned

@Rattigan, if you can't create a map you can go to the 'Request Flag/Maps Here' thread. You can ask someone to make a map and they'll make it for you.

@Rattigan, if you can't create a map you can go to the 'Request Flag/Maps Here' thread. You can ask someone to make a map and they'll make it for you.

That's a great idea, I'll do that. Thanks!

It certainly wouldn't be well advised! Kilkenny cats wouldn't be in it! The Armenian and Georgian nations have that same warm fraternal love that Ulster Unionists of the Orange persuasion and Nationalists of the Sinn Fein persuasion shareI don't quite understand the status of the Soviet-controlled Armenia - is it a satellite state, or a constituent republic of the USSR? Either way, I don't think it's possible for it to include Georgia (which should have been a constituent republic of the prewar USSR).

I don't quite understand the status of the Soviet-controlled Armenia - is it a satellite state, or a constituent republic of the USSR? Either way, I don't think it's possible for it to include Georgia (which should have been a constituent republic of the prewar USSR).

Sorry, the reference to Georgia is a typos and should be to 'Armenia.' Fixed now. Georgia is a constituent republic of the USSR.

This Armenia, is a Soviet satellite state. As with Poland, it includes bits of territory ceded from pre-war Soviet territory (in this case the territory of the Armenian SSR).

It certainly wouldn't be well advised! Kilkenny cats wouldn't be in it! The Armenian and Georgian nations have that same warm fraternal love that Ulster Unionists of the Orange persuasion and Nationalists of the Sinn Fein persuasion share

Yeah, sorry. That was a typo and should've said 'Armenia.' Fixed now.

France was a unique case, with Charles De Gaulle anxious that she should retain her independence outside of the Anglo-American orbit. He thus insisted that France have her own area of occupation in Germany, a permanent seat on the security council and undertook several measures to re-secure her colonial empire after 1945. Although French politics was thrown into chaos by the assassination of De Gaulle in 1946, of which more will be spoken of later, France remained very jealous of her independence from the British and the Americans, something which was key to President Bonnet’s decision to veto the French joining of NATO in 1949 (although she would join in 1952 under President Leclerc). When the French Union was formally constituted in 1958, it was regarded as a big failure of Anglo-American diplomacy in Westminster and Washington foreign policy circles.

Oh wow now I want to hear more. French *Union*? De Gaulle dying means French politics will be unrecognizable.

Oh wow now I want to hear more. French *Union*? De Gaulle dying means French politics will be unrecognizable.

I'm assuming it's "France and as many of its colonies as it can keep". It's also possible that France is a parliamentary republic ITTL, rather than a semi-presidential one.

What even is that map of the Balkans? There are so many problems with that I don't even know where to begin.

Also, considering how much land you gave Arabia already, they should probably get Kurdistan to unite 90% of the Kurdish speaking region.

Also also, if you really need a map I can make one. I would just probably make some actually sensible borders first...

Also, considering how much land you gave Arabia already, they should probably get Kurdistan to unite 90% of the Kurdish speaking region.

Also also, if you really need a map I can make one. I would just probably make some actually sensible borders first...

Oh wow now I want to hear more. French *Union*? De Gaulle dying means French politics will be unrecognizable.

I'm assuming it's "France and as many of its colonies as it can keep". It's also possible that France is a parliamentary republic ITTL, rather than a semi-presidential one.

An update on France will be coming in a few weeks time, covering French history up to the mid-60s. You're right that the Union is basically an attempt to ape what the Commonwealth have done but it will have different outcomes.

What even is that map of the Balkans? There are so many problems with that I don't even know where to begin.

Also, considering how much land you gave Arabia already, they should probably get Kurdistan to unite 90% of the Kurdish speaking region.

Also also, if you really need a map I can make one. I would just probably make some actually sensible borders first...

I you feel that strongly about it I'd suggest doing your own TL and I might check it out.

FWIW those post-1945 borders are no more or less strange than OTL but agree to disagree.

Most of them don't even follow natural boundaries... and Nakhchivan existing and the Middle East boundaries being almost the exact same as OTL (discounting the mergers), with a POD in the 1800s is a bit... stretching my disbelief.FWIW those post-1945 borders are no more or less strange than OTL but agree to disagree.

Most of them don't even follow natural boundaries... and Nakhchivan existing and the Middle East boundaries being almost the exact same as OTL (discounting the mergers), with a POD in the 1800s is a bit... stretching my disbelief.

Most of the changes outside the UK don't occur until the 1910s. And I think a united Arabian Hashemite kingdom, an independent Kurdistan, Greece realising the Megali idea and a greater Armenian republic existing all count as pretty different from OTL. Nakhchavin is part of the Soviet Union.

I'm assuming it's "France and as many of its colonies as it can keep". It's also possible that France is a parliamentary republic ITTL, rather than a semi-presidential one.

Let's hope so. The 5th republic is kinda awful.

An update on France will be coming in a few weeks time, covering French history up to the mid-60s. You're right that the Union is basically an attempt to ape what the Commonwealth have done but it will have different outcomes.

Honestly, I think they're too late to the party. And wouldn't be willing to make the concessions needed to make it work.

Whose northern border exactly matches that of OTL Syria and Iraq, which only came about in the '30s as a result of both Turkish negotiation and Sykes-Picot.Arabian Hashemite kingdom

Following the exact southern border of OTL Turkey (1920s invention)an independent Kurdistan,

Macedonia is just... why though? It just looks awful, and isn't even all of Macedonia if that's what you were going for.Greece realising the Megali idea

Nakhchivan only exists OTL because Stalin made it part of Azerbaijan to spite the Armenians, and play the two off each other. If the Soviets were building up Armenia as a puppet state, they wouldn't want the exclave, and drop it with the Armenians; and without Stalin around the muck up the borders, Artsakh would also probably be part of Armenia.greater Armenian republic existing all count as pretty different from OTL. Nakhchavin is part of the Soviet Union.

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Share: