Wexit: Provincial Alienation, Then and Now

In 1945, the major constitutional question which seemed to face Canadian politics was that of the status of Quebec. Particularly during the 1960s, the cultural revolution in the province spilled over into politics and for the first time in several decades raised the serious prospect of secession. Former French President Philippe Leclerc, about the only French politician of any stature who was still regarded warmly in the Anglophone global community after about 1960, was known to have privately favoured Quebecois independence, resulting in a bizarre attempt by the Pearson government to block him from getting a visa for a visit to the province in 1967, which caused a seemingly-serious diplomatic incident between France and the Commonwealth.

However, from the potential moment of crisis in the late 1960s, the ‘Quebec libre’ moment dissipated. How and why it did so is still a matter of debate. On a purely cultural level, many have argued that the movement was really just a modernisation one, focused on bringing the province into cultural ‘modernity’ through processes such as the reduction in the powers of the Church and, in an environment of economic destabilisation in the 1970s, this became far less relevant an issue. Politically, key considerations were Pierre Trudeau taking over from Pearson in June 1970, the failure of Pierre Bourgault’s Rally for National Independence party to make a breakthrough in the elections of October that year and the ambivalence or hostility towards independence itself from important figures such as Jean Drapeau, Therese Casgrain and Pierre Laporte.

Generally, however, the sting was taken out of the movement by developments in the Commonwealth more widely and the dominant Liberal Party within Canada itself. On the Commonwealth level, the increased importance of Commonwealth institutions and ‘the Commonwealth’ as a general pluricontinental and multicultural identity could decrease, for those who cared about these things, the importance of being ‘Anglo-Canadians’ or ‘French-Canadians.’ Secondly, whether by design or accident, the top level of the Canadian federal government between 1945 and 2020 was, in practice dominated by people from either Ontario (King, Diefenbaker, Pearson, Copps, Stronach and Justin Trudeau) or from Quebec itself (St. Laurent, Pierre Trudeau, Pepin, Chretien, Layton and Dion). Only Flora MacDonald (Nova Scotia) and Gary Doer (Manitoba) broke up this duopoly in 24 Sussex Drive.

Thus by the year 2000 probably the most pronounced serparatist movement within Canada was actually in the western provinces. However, for many years any movement for separatism was held back by a number of incoherencies within the wider movement. In the first place, theorists of western alienation struggled to articulate a coherent national vision that coherently covered the diverse polities of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. At the very least there was a legitimate question of what it was to be called. ‘Western alienation’ or ‘Prairie and Arctic nationalism’ became the most common expressions but both seemed somehow unsatisfactory. Secondly, it was never obvious whether such a national vision would be fundamentally progressive or reactionary in its orientation: on the one hand, such figures were behind the move, in 2001, to end the compulsory teaching of French in state schools in the western provinces; on the other hand, they also played an important part in lobbying for raising Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut to full provincial status in 1999.

The cause of Prairie and Arctic nationalism was also held back by the lack of a coherent political voice at federal level. While it is true that the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (“CCF”) fared better in the western provinces than in elsewhere, their leaders were, at best, ambivalent about the prospect of sovereignty and to a great extent functioned as little more than a kooky branch office of the Liberals by the 1980s. For a brief period after Doer’s ousting from office by Chretien’s allies in the ‘Montreal Mafia’ (with many claiming that Doer’s western origins played a part in the Liberal establishment mistrusting him), it looked like he might found a specifically western party, especially when the CCF was one of the parties folded into his New Democrats in 2002. However, during Doer’s time in government he did not materially change the general nature of Canadian federal government, even as he embarked on an ambitious program of reform during his six years in office. In any event, when Doer lost the 2009 election (to a Liberal Party lead by the Ontarian Belinda Stronach) he was replaced as leader by the Quebecer Jack Layton.

But by this time western alienation had finally found something that all the seven provinces cold hang their hats on: economic failure. As Canada as a whole entered a prolonged industrial and services boom in the 1990s, the prairie and arctic provinces found themselves left behind, still heavily reliant on agriculture, tourism and mining (with the notable exception of the financial and services centre of Vancouver and its environs). Politicians such as Ralph Klein and Ed Stelmach found some success in their home province of Alberta claiming that Ottawa-based regulations (particularly on the environment) were holding back the west from fully exploiting its vast natural resources. When allied with a concern for the economic plight of the Inuit in the north, such an ideology had a broad appeal that was realised when the Prairie and Arctic Party (“PAP”) began to win elections at provincial level in the first and second decade of the 21st century.

PAP found its position greatly helped by chaos in Ottawa. The Liberals returned to power in the 2018 federal elections under the leadership of the telegenic Justin Trudeau, ejecting Jack Layton’s New Democratic government. However, Trudeau’s government was immediately caught in scandal involving both the prime minister’s history of racist fancy dress and his sacking of the Attorney General (and British Columbian) Jody Wilson-Raybould in an attempt to suppress a negative report on a prominent Quebec construction company. Trudeau resigned under pressure after only a year in office, replaced by his deputy Stephane Dion (from Quebec) on an interim basis and then, following a leadership election in 2020, Yves-François Blanchet (also from Quebec). Blanchet was not just a francophone but someone who primarily spoke French, speaking English on only two days per week, further creating an alienation between the (largely) monolingual west and north and the bilingual east.

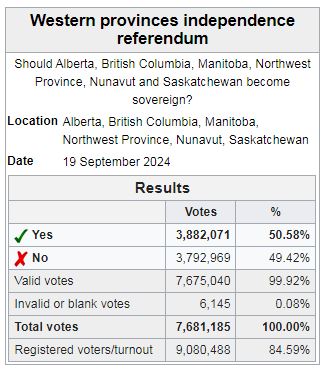

Blanchet went to the country again and the PAP was able to capitalise on his francophone leanings in the subsequent April 2020 elections. Although the Liberals managed to scrape a bare majority, the PAP won either a majority or a plurality of seats in all of the western and northern provinces to become firmly the third party in the commons and style themselves the authentic voice of the west. Dan Brooks, the party’s leader at a federal level, became a prominent national figure and used the first session of the new federal parliament to repeat his party’s commitment to hold an independence referendum in the seven provinces. Brooks found his desire for a referendum matched by the ambivalence with which Blanchet and the other people at the top of the Liberals regarded the issue of secession. (The Liberals did not need western seats to get majorities, while many thought that the New Democrats did.) In January 2022, the federal government began to negotiate with PAP, resulting in an agreement in October 2022 that confirmed that referendums would be held in the western provinces. An act passed in June 2023 set the terms of the question, elector eligibility and the date as 19 September 2024.

At first, the referendum aroused little discussion, either in Ottawa or the Commonwealth offices in London. Support for secession (as opposed to generalised discontent with Ottawa) rarely rose above 40% for any consistent period of time and most were inclined to view the growth of the PAP as the reflowering of the Canadian centre-right that had been considered dead since the collapse of the Progressive Conservatives amidst the disaster of the 1981 elections. Certainly, the leadership of the PAP did set itself up as a pro-business party. But at the same time it assiduously courted the votes of First Nations members and the working classes through a variety of redistributive policies and proposals. The PAP was a nationalist party, pure and simple, and this is what made it both harder to pin down and harder to defeat.

As the date drew closer to 19 September, the polls indicated that opinion was becoming ever tighter, with the PAP playing heavily on themes of economic disenchantment while the remain campaign attempted to play up themes surrounding the uncertainty of secession. With the referendum only a month away, a number of polls began to show the secession side winning, something which panicked several federal Canadian and Commonwealth figures into making whistlestop tours of the provinces to back a remain vote. Nevertheless, when polling day came out, the exit poll predicted a 52-48 margin of victory to remain.

The end result was tighter and worse than predicted, with the ‘Yes’ campaign winning by just under 90,000 votes, or 1.16%. In Ottawa, Blanchet was shell shocked by the result: he had been ambivalent about losing the western provinces but, now that the results were in, it wasn’t what he wanted his legacy to be. By all accounts, he had to be talked out of resigning by his advisors and bundled into a plane to London for an emergency prime ministers’ conference.

Famously, Blanchet began the conference by commenting “you’ve all seen what has just happened in my country. What can you do for me?”

What indeed?