Now for something completely different. I've previously said that pretty much every other country ITTL is meaningfully the same as IOTL but with a few exceptions. It should now be clear that one of these exceptions is the US...

From left to right - Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan, Eugene V. Debs, Eugene W. Chafin and Daniel De Leon

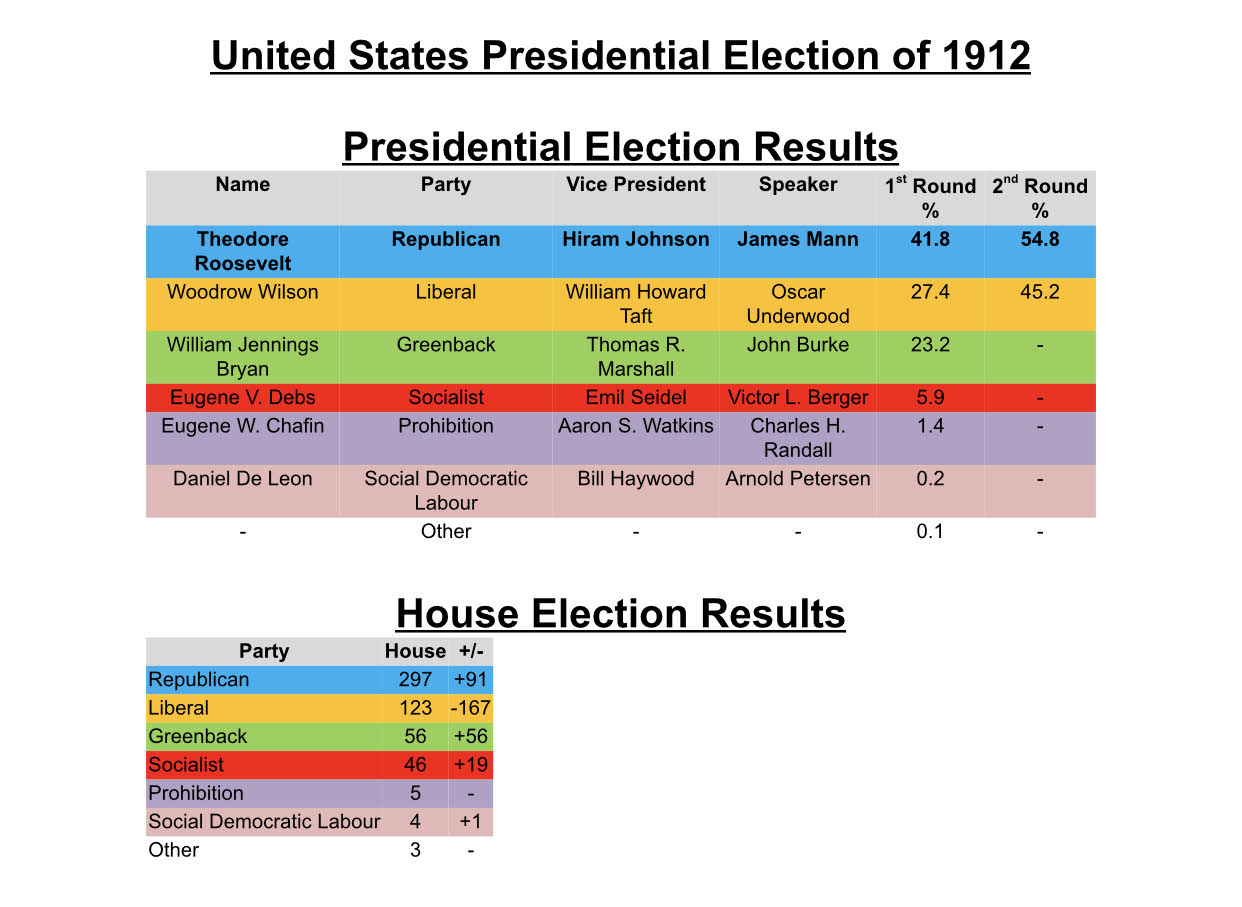

The United States presidential election of 1912 was held on Saturday 2 November 1912 and Saturday 16 November 1912. It was the 32nd quadrennial presidential election in the history of the United States and the 9th to have been held under the rules of the Second American Constitution. It was won by New York Governor and former-Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt defeated a field of seven other candidates, winning 41.8% of the vote in the first round and 54.8% in the run-off, thus foiling President William Jennings Bryan in his bid to become the first president to serve for more than two terms under the Second Constitution. In the House elections held at the same time, the Republicans picked up 91 seats to gain a majority of 31. Roosevelt’s running mates were California Governor Hiram Johnson (as Vice President) and Illinois Representative James Mann (as Speaker).

Backed by all notable factions of his party, Roosevelt, who had served as Vice President from 1901 to 1905 and as Governor of New York from 1908 to 1912, was adopted as the Republican candidate after two rounds of balloting at the Republican National Convention. Displeased with Bryan’s actions as president and the way that he had been sidelined since the Liberals had lost control of the Senate in 1910, Vice President Woodrow Wilson challenged Bryan at the 1912 Liberal National Convention. After Wilson’s conservative allies narrowly prevailed at the convention, Bryan rallied his supporters and launched a new party called the Greenback Party, with himself as the presidential candidate. Meanwhile, the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Labor Party re-nominated their perennial standard-bearers, Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon, respectively. The Prohibition Party nominated Arizona lawyer Eugene W. Chafin.

The election was a bitter and divisive one, mainly contested between the frontrunners of Roosevelt, Wilson and Bryan. Roosevelt’s platform called for an eight-hour workday, female emancipation and a stronger federal role in the economy. Wilson called for tariff reductions, cuts to social insurance programs and banking reform (although he did not call for a return to the gold standard, as he had done as recently as 1907). Bryan ran on a defence of his two terms as president and attempted to portray Wilson as corrupt and a betrayer of Liberal principles. Debs and De Leon claimed that the main three candidates were largely financed by trusts and corrupt business interests while Chafin and his running mates urged voters to help the Prohibitionists hold the balance of power in the new House.

The Republicans skillfully exploited the split between the Liberals and the Greenbacks, winning over former Bryan voters with their progressive policies and reassuring so-called ‘Bourbon’ Liberals through Roosevelt’s personal charm. His 41.8% in the first round was the highest by any first-round candidate since Abraham Lincoln in the 1884 election and he convincingly won the run-off against Wilson by convincing Greenback voters to come over to him. The Socialist result of 5.9% in the presidential election and nearly 50 seats in the house represents, to date, the electoral high point of their party.

The split in the Liberal Party is believed to have been a major factor in the Liberals’ losses in the election, which included not only losing the Presidency but also 167 seats in the House to all of the Republicans, Greenbacks, Socialists and Social Democratic Labor Party. But it is not clear exactly how big a cause this was. Some candidates stood calling for a reunification of the Liberals and the Greenbacks, others appear to have backed both Wilson and Bryan and some campaigned as so-called 'Liberal Greenbacks.' Few sources are able to agree on exact numbers, and even in the contemporary records held by the two parties, some House candidates were claimed for both sides. Furthermore, many analysts at the time believed that the popular mood had turned against Bryan, suggesting that a Republican win could have occurred in any event. By one estimate, there were 29 seats where Greenbacks and Liberals stood against one another. This is thought to have cost them at least 14 seats, 10 of them to the Republicans, so in theory a reunited Liberal Party would have been much closer to the Republicans in the House and might even have won the Presidency (Wilson’s and Bryan’s combined vote total in the first round was 50.6%). However, in reality the two factions were on poor terms and Bryan was hoping for cooperation between the Greenbacks and the Republicans in the House (and possibly even a cabinet position for himself).

* * *

From left to right - Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan, Eugene V. Debs, Eugene W. Chafin and Daniel De Leon

The United States presidential election of 1912 was held on Saturday 2 November 1912 and Saturday 16 November 1912. It was the 32nd quadrennial presidential election in the history of the United States and the 9th to have been held under the rules of the Second American Constitution. It was won by New York Governor and former-Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt defeated a field of seven other candidates, winning 41.8% of the vote in the first round and 54.8% in the run-off, thus foiling President William Jennings Bryan in his bid to become the first president to serve for more than two terms under the Second Constitution. In the House elections held at the same time, the Republicans picked up 91 seats to gain a majority of 31. Roosevelt’s running mates were California Governor Hiram Johnson (as Vice President) and Illinois Representative James Mann (as Speaker).

Backed by all notable factions of his party, Roosevelt, who had served as Vice President from 1901 to 1905 and as Governor of New York from 1908 to 1912, was adopted as the Republican candidate after two rounds of balloting at the Republican National Convention. Displeased with Bryan’s actions as president and the way that he had been sidelined since the Liberals had lost control of the Senate in 1910, Vice President Woodrow Wilson challenged Bryan at the 1912 Liberal National Convention. After Wilson’s conservative allies narrowly prevailed at the convention, Bryan rallied his supporters and launched a new party called the Greenback Party, with himself as the presidential candidate. Meanwhile, the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Labor Party re-nominated their perennial standard-bearers, Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon, respectively. The Prohibition Party nominated Arizona lawyer Eugene W. Chafin.

The election was a bitter and divisive one, mainly contested between the frontrunners of Roosevelt, Wilson and Bryan. Roosevelt’s platform called for an eight-hour workday, female emancipation and a stronger federal role in the economy. Wilson called for tariff reductions, cuts to social insurance programs and banking reform (although he did not call for a return to the gold standard, as he had done as recently as 1907). Bryan ran on a defence of his two terms as president and attempted to portray Wilson as corrupt and a betrayer of Liberal principles. Debs and De Leon claimed that the main three candidates were largely financed by trusts and corrupt business interests while Chafin and his running mates urged voters to help the Prohibitionists hold the balance of power in the new House.

The Republicans skillfully exploited the split between the Liberals and the Greenbacks, winning over former Bryan voters with their progressive policies and reassuring so-called ‘Bourbon’ Liberals through Roosevelt’s personal charm. His 41.8% in the first round was the highest by any first-round candidate since Abraham Lincoln in the 1884 election and he convincingly won the run-off against Wilson by convincing Greenback voters to come over to him. The Socialist result of 5.9% in the presidential election and nearly 50 seats in the house represents, to date, the electoral high point of their party.

The split in the Liberal Party is believed to have been a major factor in the Liberals’ losses in the election, which included not only losing the Presidency but also 167 seats in the House to all of the Republicans, Greenbacks, Socialists and Social Democratic Labor Party. But it is not clear exactly how big a cause this was. Some candidates stood calling for a reunification of the Liberals and the Greenbacks, others appear to have backed both Wilson and Bryan and some campaigned as so-called 'Liberal Greenbacks.' Few sources are able to agree on exact numbers, and even in the contemporary records held by the two parties, some House candidates were claimed for both sides. Furthermore, many analysts at the time believed that the popular mood had turned against Bryan, suggesting that a Republican win could have occurred in any event. By one estimate, there were 29 seats where Greenbacks and Liberals stood against one another. This is thought to have cost them at least 14 seats, 10 of them to the Republicans, so in theory a reunited Liberal Party would have been much closer to the Republicans in the House and might even have won the Presidency (Wilson’s and Bryan’s combined vote total in the first round was 50.6%). However, in reality the two factions were on poor terms and Bryan was hoping for cooperation between the Greenbacks and the Republicans in the House (and possibly even a cabinet position for himself).

Last edited: