Power to the People? Elections to the Commonwealth Assembly

The expulsion of South Africa from the Commonwealth both confirmed the power of the individual states and also stimulated demand for greater democratic representation within the organisation’s institutions. Naturally, the focus of this became the Commonwealth Assembly. Although it sounded like an organisation that should be elected, no provisions were made in the Treaty of London or Ottawa Declaration for Commonwealth elections and all members were appointed by national governments on a (broadly speaking) non-partisan basis. The Assembly had thus become a technocratic regulatory body, populated largely by diplomats and civil servants of various stripes. Michael Collins, the veteran Irish politician, had lead the institution capably and in a non-partisan manner, with most regulations being passed by consensus (with the exception of the highly divisive ones regarding Rhodesia and South Africa’s expulsion itself). The high level deliberative body remained the Commonwealth Cabinet in collaboration with the Prime Ministers’ Conferences and/or the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

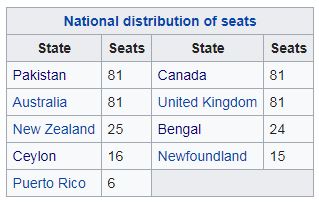

Following the expulsion of South Africa, the number of seats in the Assembly was reorganised to reflect the new balance of power within the Commonwealth, resulting in the following division of seats by country:

As can be seen, the distribution represented pure power politics rather than any attempt towards an accurate representation of the populations. Thus Canada (population: 17.9 million) and Australia (10.3 million) had more than three times as many Assembly Members (known as ‘AMs’) than Bengal (85.2 million). Pakistan took a large share of the new AMs, recognition of its equal ranking as a member of the ‘Big Four'. The Big Four were nervous about the possibility of diluting their power in the event of ending the old appointments procedure but agreed to let elections take place in 1962 provided that the previous distribution of seats remained in place.

There were no rules on the system of election to be used. The Big Four and New Zealand all used their first past the post system. Bengal used a proportional system but divided up between different religious franchises, as was the case with their domestic voting arrangements. Ceylon, Newfoundland and Puerto Rico all used proportional representation, albeit with different methods of seat allocation.

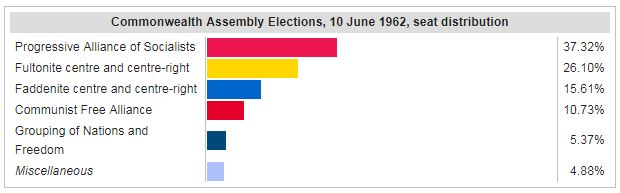

When the elections rolled around, the different intensity with which the political movements in each country competed were key to deciding the results. The left wing and/or progressive parties campaigned together under the banner of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists (“PAS”). Progressive politicians such as Lester Pearson and Walter Nash conducted a Commonwealth-wide campaign taking in stops in every member state. Right wing and centrist parties, however, were more circumspect in their campaigns: the Australian Liberal Party, for example, campaigned largely on domestic issues, attacking the incumbent Labor Party. The Commonwealth’s communist parties also banded together as the Communist Free Alliance under the chairmanship of the Anglo-Indian-Swedish intellectual R. Palme Dutt. More disconcertingly, a coalition of far right parties (some of which explicitly campaigned opposing South Africa’s expulsion) formed under A.K. Chesterton.

Making use of lessons learned from Labour’s ruthless election-winning tactics, PAS won the most seats in the assembly with 153. The grouping of miscellaneous parties of the Commonwealth’s centre and centre-right together had 171. However, both were short of the 206 seats required to make up a majority. Over the course of a series of cross-party talks, a majority of the centre and centre-right AMs agreed to support PAS’s nominee for Speaker, Anthony Crosland. These 107 individuals, under the leadership of Davie Fulton, would later form the Liberals and Democrats grouping in 1963, while the remaining 64 AMs would form the Conservatives and Reformist grouping under Arthur Fadden.

Crosland thus took office as Speaker of the Commonwealth Assembly in June 1962. Although this position allowed him to control the Assembly’s business, he was aware that his arrangement with the Liberals and Democrats was some way short of a full coalition. He thus prepared to manage Commonwealth business in the same consensual manner as Collins had done, even though he and his chief of staff Peter Shore had ambitious plans for the future of the organisation.

Under Crosland, the Commonwealth Assembly emphasised its powers to admit new members and went on a throughgoing recruitment drive. Under his watch, not only did Crosland make good on the promises of various prime ministers and grant full membership to Rhodesia (31 December 1963), Sarawak (16 September 1964) and the East Indies (9 August 1965), but decolonisation was fast-tracked and membership extended to the West Indies (31 May 1963) and East Africa (12 December 1964). Further down the line, Crosland’s tenure would also see membership expanding to include the Bahamas (10 July 1968), the Pacific Islands (4 June 1970), Papua New Guinea (16 September 1975) and, on the last day before he retired from the role, Belize (8 June 1981).

The expulsion of South Africa from the Commonwealth both confirmed the power of the individual states and also stimulated demand for greater democratic representation within the organisation’s institutions. Naturally, the focus of this became the Commonwealth Assembly. Although it sounded like an organisation that should be elected, no provisions were made in the Treaty of London or Ottawa Declaration for Commonwealth elections and all members were appointed by national governments on a (broadly speaking) non-partisan basis. The Assembly had thus become a technocratic regulatory body, populated largely by diplomats and civil servants of various stripes. Michael Collins, the veteran Irish politician, had lead the institution capably and in a non-partisan manner, with most regulations being passed by consensus (with the exception of the highly divisive ones regarding Rhodesia and South Africa’s expulsion itself). The high level deliberative body remained the Commonwealth Cabinet in collaboration with the Prime Ministers’ Conferences and/or the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

Following the expulsion of South Africa, the number of seats in the Assembly was reorganised to reflect the new balance of power within the Commonwealth, resulting in the following division of seats by country:

As can be seen, the distribution represented pure power politics rather than any attempt towards an accurate representation of the populations. Thus Canada (population: 17.9 million) and Australia (10.3 million) had more than three times as many Assembly Members (known as ‘AMs’) than Bengal (85.2 million). Pakistan took a large share of the new AMs, recognition of its equal ranking as a member of the ‘Big Four'. The Big Four were nervous about the possibility of diluting their power in the event of ending the old appointments procedure but agreed to let elections take place in 1962 provided that the previous distribution of seats remained in place.

There were no rules on the system of election to be used. The Big Four and New Zealand all used their first past the post system. Bengal used a proportional system but divided up between different religious franchises, as was the case with their domestic voting arrangements. Ceylon, Newfoundland and Puerto Rico all used proportional representation, albeit with different methods of seat allocation.

When the elections rolled around, the different intensity with which the political movements in each country competed were key to deciding the results. The left wing and/or progressive parties campaigned together under the banner of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists (“PAS”). Progressive politicians such as Lester Pearson and Walter Nash conducted a Commonwealth-wide campaign taking in stops in every member state. Right wing and centrist parties, however, were more circumspect in their campaigns: the Australian Liberal Party, for example, campaigned largely on domestic issues, attacking the incumbent Labor Party. The Commonwealth’s communist parties also banded together as the Communist Free Alliance under the chairmanship of the Anglo-Indian-Swedish intellectual R. Palme Dutt. More disconcertingly, a coalition of far right parties (some of which explicitly campaigned opposing South Africa’s expulsion) formed under A.K. Chesterton.

Making use of lessons learned from Labour’s ruthless election-winning tactics, PAS won the most seats in the assembly with 153. The grouping of miscellaneous parties of the Commonwealth’s centre and centre-right together had 171. However, both were short of the 206 seats required to make up a majority. Over the course of a series of cross-party talks, a majority of the centre and centre-right AMs agreed to support PAS’s nominee for Speaker, Anthony Crosland. These 107 individuals, under the leadership of Davie Fulton, would later form the Liberals and Democrats grouping in 1963, while the remaining 64 AMs would form the Conservatives and Reformist grouping under Arthur Fadden.

Crosland thus took office as Speaker of the Commonwealth Assembly in June 1962. Although this position allowed him to control the Assembly’s business, he was aware that his arrangement with the Liberals and Democrats was some way short of a full coalition. He thus prepared to manage Commonwealth business in the same consensual manner as Collins had done, even though he and his chief of staff Peter Shore had ambitious plans for the future of the organisation.

Under Crosland, the Commonwealth Assembly emphasised its powers to admit new members and went on a throughgoing recruitment drive. Under his watch, not only did Crosland make good on the promises of various prime ministers and grant full membership to Rhodesia (31 December 1963), Sarawak (16 September 1964) and the East Indies (9 August 1965), but decolonisation was fast-tracked and membership extended to the West Indies (31 May 1963) and East Africa (12 December 1964). Further down the line, Crosland’s tenure would also see membership expanding to include the Bahamas (10 July 1968), the Pacific Islands (4 June 1970), Papua New Guinea (16 September 1975) and, on the last day before he retired from the role, Belize (8 June 1981).