You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Anglo-Saxon Social Model

- Thread starter Rattigan

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030I'm pretty sure he mentioned they were builtWould this timeline ever build this?

Would this timeline ever build this?

I'm pretty sure he mentioned they were built

I did mention that in a discussion a while ago because I’ve always thought something like that sounds really cool. But I think someone else on this forum queried how theoretically workable it would be.

Windows95

Banned

Such a shame that is theoretical and if it really works.But I think someone else on this forum queried how theoretically workable it would be.

Likely needs something like mass production of carbon nanotubes to be physically feasible.I mean... it is a shame that it is theoretical. That makes me doubt whether the Skyhook would really work on Earth with the present materials we have.

apparently it would be built out of a commercial material called spectra 2000 so its feasible to be built today, its just launch paradox that stops us, aka too expensive to launch too many things but not enough stuff to launch to make building a cheaper launch system viable you would need a government willing to make a leap of faith to build these stuff.Likely needs something like mass production of carbon nanotubes to be physically feasible.

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025)

Death of a Party Redux: This Time It's Labour

Douglas Alexander and Ed Miliband look pensive the morning after the latter was confirmed as Prime Minister, September 2025

Douglas Alexander had never expected to become the Prime Minister. His career thusfar had been solid but unflashy: academia at the University of Edinburgh, followed by a position as AM in Scotland (where he served as Transport Minister 2003-05 and Finance Minister 2005-09) before becoming an MP in 2009. There he had been served in the Shadow Cabinet as Shadow Minister for Scotland before entering government with Cooper in 2014. He served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (2014-15), Minister for International Development (2015-18), Minister for Supply (2018-19), Chief Whip (2019-23) and after the 2023 election, as Lord President of the Council. His move out of the Whips’ Office after 2023 was interpreted as a bit of a demotion - by many accounts Cooper was furious that he had not kept the backbenchers more in line over the reintroduction of public transport tickets in 2021 - and he had spent the next 18 months a quiet figure, too small to have much of an influence on government policy but too large to risk cutting out entirely.

Thus, when Cooper announced her resignation in December 2024, many were surprised to remember that Alexander was still there. However, he found himself well-placed to deal with the task in hand: well known to backbenchers from his time as Chief Whip; personally untouched by Operation Car Wash; close enough to Cooper’s faction to not promise a radical change of direction; and not too closely associated with them to alienate other factions. The first factor was really the most important as the biggest item on Alexander’s in-tray was not a policy programme as much as an existential crisis facing the party.

In January 2025, Alexander arranged a summit meeting at Chequers between the party leadership and representatives of the principal organisations of the party’s left and right wings: Louise Haigh of the leftist Tribune Group and Chuka Ummuna of the centrist Compass Group. These talks ended amicably enough - the most notable upshot being agreement for both groups to close ranks for the party’s betterment with Ummuna and Haigh joining the cabinet - but it failed to clear the smell of corruption around the party. Alexander tried to tamp down issues at first by extending his ‘interim’ leadership as long as possible and pushing through a popular legislative campaign including spending increases, eye-catching proposals on healthcare and bringing forward a programme of rail upgrades.

This programme was generally well-received and returned Labour to a lead in the polls. But it could not go on forever and eventually Alexander was forced to concede (allegedly at the urging of the Palace) that a leadership election would have to take place over the summer recess of 2025. Haigh was soon chosen as the voice of the Tribune Group as their candidate and, after much discussion, Compass in the end put up Alison McGovern as their standard-bearer. Alexander initially floated the idea of launching himself as the ‘compromise’ candidate but found few people who actively supported him, even if there were even fewer who actively disliked him. The identity of the candidate of the Labour ‘establishment’ or ‘moderates’ was key, given that this person was almost certain to be the eventual winner. Many candidates, such as Chancellor Rachel Reeves and Foreign Secretary Andy Burnham were mooted but the eventual candidate proved to be Ed Miliband.

Miliband had served as Lord Chancellor during Cooper’s third term and under Alexander, having previously served in a variety of ministerial roles and prior to that had been a successful First Minister in London (2010-18). He had the classic make-up of a Labour leader - personable, a savvy internal operator and shrewd intelligence - and had enough leftist bona fides from his time in London to reassure soft left MPs. In the first round of voting Miliband comfortably finished first place, with Reeves just edging out Haigh to go into the second round. As was almost par for the course by now, Haigh threw her followers behind Miliband in the second round and he eased to victory in a vote on 14 July 2025. In victory, Miliband again took the normal Labour tac and rewarded his opponents for a race well run: Haigh and fellow-Tribuneist Michael Chessum joined the cabinet and Reeves was confirmed in her place as Chancellor.

The normal Labour tac, however, looked like it may no longer work. Miliband was a product of the Labour machine and had won in the traditional machine politician manner. But, now, that was the problem. Perhaps the most eloquent foreshadowing came as Miliband delivered his acceptance speech, which had to be cut short because of the announcement that Queen Elizabeth II had died suddenly after 73 years and 159 days on the throne.

On the political front, an early flashpoint came on 28 July, only a fortnight after Miliband’s assumption of the leadership, when Umunna contributed an article to the ‘New Statesman.’ Purportedly a personal account of the leadership election, in reality the 5,000 word article was a thinly-veiled criticism of the spoils system that had operated inside Labour for eighty years. As many people pointed out in the subsequent furore, there was more than a hint of hypocrisy in Umunna’s remarks, given that Compass had enthusiastically participated in it up until that point. Indeed, the ‘New Statesman’s own political editor Patrick Magiure rather dismissively wrote that Umunna’s main criticism seemed to be that the system didn’t include him.

But, of course, someone can be both right and a hypocrite. With the fallout from Car Wash and Leveson echoing around the country, fewer and fewer people found loyalty to the party to be a good enough reason to keep hold their tongue and change things from the inside.

The final straw proved to be the Labour conference in September 2025. Tristram Hunt, the International Development Secretary, Compass member and known ally of Umunna, put down a motion regarding the ability of the government to distribute Commonwealth international development money under the auspices of another country (the relevant one being Azawad to various western African states). However, the motion was defeated in both cabinet discussions and the subsequent floor debate, leading to Hunt being quietly shuffled into the lesser Agriculture Ministry. Hunt’s diagonal-downwards move meant that the only Compass member left in the cabinet (although there still were members from the party’s centre and right) was Rachel Reeves.

17 November 2025 was a momentous day in British politics. Virtually all MPs, journalists and members of the public awoke to be told that the government’s majority had been slashed to the bare minimum. With a veil of secrecy that would have made the Five Eyes Agency proud, Umunna had managed to corral 21 other MPs into resigning from Labour and forming their own grouping. Two days later, 13 more Labour backbenchers quit their party, stripping the government of its majority. Rumours abounded that Reeves was going to follow many of her ex-Compass colleagues out of Labour but Miliband managed to keep her in his cabinet and stop the hemorrhaging at 35.

Quite to many people’s surprise, a closer inspection of the defectors revealed them to have all been joint members of the Co-operative Party. Since 1927, the Co-operative Party had been in an electoral pact with Labour and had seemed to many to be nothing more than a slightly quirky extra designation for many Labour MPs who wished to signal their commitment to the more bourgeois cooperative movement rather than their close ties to the trades unions, with the distinction being, at best, considered academic. However, this shift reflected both the general split within British centre-left politics (between a radical if bourgeois and bourgeois-adjacent politics and a more workerist trades unionist one) that harked back to the divides between Labour and Lloyd George’s New Liberals in the 1920s. It also spoke well of the success of the general centre-left project over the previous century and a half, with the ‘bourgeois’ designation no longer really referring to material conditions but speaking more to attitudes and taste. In this sense the revolt of the Co-operative MPs was a very Hanoverian-sounding rejection of the ‘Old Corruption’ of Labour and a hope to recreate something with, broadly, the same values but less of the brutal machine politics.

All of a sudden, a silence fell across the Parliament, like the calm before a shootout in a Western. Labour was wounded and, to continue the analogy, had taken a bullet to the side: they had lost their majority, now suffered from the stench of corruption and faced two parties (the Progressives and Umunna’s grouping, which at this stage was going by the name New Labour but which would formally go under the name the Co-operative Party from December 2025) that could challenge them on the centre-left and with swing voters. But, on the other hand, they were far from being out. The major unions had stuck with the party, the Liberals were still wheezing under a succession of leaders and the potential longevity of the Progressives and New Labour was still in doubt. The question was, would any of the opposition parties risk a motion of no confidence when an election, in this uncertain political moment, meant that they might be annihilated?

Douglas Alexander and Ed Miliband look pensive the morning after the latter was confirmed as Prime Minister, September 2025

Douglas Alexander had never expected to become the Prime Minister. His career thusfar had been solid but unflashy: academia at the University of Edinburgh, followed by a position as AM in Scotland (where he served as Transport Minister 2003-05 and Finance Minister 2005-09) before becoming an MP in 2009. There he had been served in the Shadow Cabinet as Shadow Minister for Scotland before entering government with Cooper in 2014. He served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (2014-15), Minister for International Development (2015-18), Minister for Supply (2018-19), Chief Whip (2019-23) and after the 2023 election, as Lord President of the Council. His move out of the Whips’ Office after 2023 was interpreted as a bit of a demotion - by many accounts Cooper was furious that he had not kept the backbenchers more in line over the reintroduction of public transport tickets in 2021 - and he had spent the next 18 months a quiet figure, too small to have much of an influence on government policy but too large to risk cutting out entirely.

Thus, when Cooper announced her resignation in December 2024, many were surprised to remember that Alexander was still there. However, he found himself well-placed to deal with the task in hand: well known to backbenchers from his time as Chief Whip; personally untouched by Operation Car Wash; close enough to Cooper’s faction to not promise a radical change of direction; and not too closely associated with them to alienate other factions. The first factor was really the most important as the biggest item on Alexander’s in-tray was not a policy programme as much as an existential crisis facing the party.

In January 2025, Alexander arranged a summit meeting at Chequers between the party leadership and representatives of the principal organisations of the party’s left and right wings: Louise Haigh of the leftist Tribune Group and Chuka Ummuna of the centrist Compass Group. These talks ended amicably enough - the most notable upshot being agreement for both groups to close ranks for the party’s betterment with Ummuna and Haigh joining the cabinet - but it failed to clear the smell of corruption around the party. Alexander tried to tamp down issues at first by extending his ‘interim’ leadership as long as possible and pushing through a popular legislative campaign including spending increases, eye-catching proposals on healthcare and bringing forward a programme of rail upgrades.

This programme was generally well-received and returned Labour to a lead in the polls. But it could not go on forever and eventually Alexander was forced to concede (allegedly at the urging of the Palace) that a leadership election would have to take place over the summer recess of 2025. Haigh was soon chosen as the voice of the Tribune Group as their candidate and, after much discussion, Compass in the end put up Alison McGovern as their standard-bearer. Alexander initially floated the idea of launching himself as the ‘compromise’ candidate but found few people who actively supported him, even if there were even fewer who actively disliked him. The identity of the candidate of the Labour ‘establishment’ or ‘moderates’ was key, given that this person was almost certain to be the eventual winner. Many candidates, such as Chancellor Rachel Reeves and Foreign Secretary Andy Burnham were mooted but the eventual candidate proved to be Ed Miliband.

Miliband had served as Lord Chancellor during Cooper’s third term and under Alexander, having previously served in a variety of ministerial roles and prior to that had been a successful First Minister in London (2010-18). He had the classic make-up of a Labour leader - personable, a savvy internal operator and shrewd intelligence - and had enough leftist bona fides from his time in London to reassure soft left MPs. In the first round of voting Miliband comfortably finished first place, with Reeves just edging out Haigh to go into the second round. As was almost par for the course by now, Haigh threw her followers behind Miliband in the second round and he eased to victory in a vote on 14 July 2025. In victory, Miliband again took the normal Labour tac and rewarded his opponents for a race well run: Haigh and fellow-Tribuneist Michael Chessum joined the cabinet and Reeves was confirmed in her place as Chancellor.

The normal Labour tac, however, looked like it may no longer work. Miliband was a product of the Labour machine and had won in the traditional machine politician manner. But, now, that was the problem. Perhaps the most eloquent foreshadowing came as Miliband delivered his acceptance speech, which had to be cut short because of the announcement that Queen Elizabeth II had died suddenly after 73 years and 159 days on the throne.

On the political front, an early flashpoint came on 28 July, only a fortnight after Miliband’s assumption of the leadership, when Umunna contributed an article to the ‘New Statesman.’ Purportedly a personal account of the leadership election, in reality the 5,000 word article was a thinly-veiled criticism of the spoils system that had operated inside Labour for eighty years. As many people pointed out in the subsequent furore, there was more than a hint of hypocrisy in Umunna’s remarks, given that Compass had enthusiastically participated in it up until that point. Indeed, the ‘New Statesman’s own political editor Patrick Magiure rather dismissively wrote that Umunna’s main criticism seemed to be that the system didn’t include him.

But, of course, someone can be both right and a hypocrite. With the fallout from Car Wash and Leveson echoing around the country, fewer and fewer people found loyalty to the party to be a good enough reason to keep hold their tongue and change things from the inside.

The final straw proved to be the Labour conference in September 2025. Tristram Hunt, the International Development Secretary, Compass member and known ally of Umunna, put down a motion regarding the ability of the government to distribute Commonwealth international development money under the auspices of another country (the relevant one being Azawad to various western African states). However, the motion was defeated in both cabinet discussions and the subsequent floor debate, leading to Hunt being quietly shuffled into the lesser Agriculture Ministry. Hunt’s diagonal-downwards move meant that the only Compass member left in the cabinet (although there still were members from the party’s centre and right) was Rachel Reeves.

17 November 2025 was a momentous day in British politics. Virtually all MPs, journalists and members of the public awoke to be told that the government’s majority had been slashed to the bare minimum. With a veil of secrecy that would have made the Five Eyes Agency proud, Umunna had managed to corral 21 other MPs into resigning from Labour and forming their own grouping. Two days later, 13 more Labour backbenchers quit their party, stripping the government of its majority. Rumours abounded that Reeves was going to follow many of her ex-Compass colleagues out of Labour but Miliband managed to keep her in his cabinet and stop the hemorrhaging at 35.

Quite to many people’s surprise, a closer inspection of the defectors revealed them to have all been joint members of the Co-operative Party. Since 1927, the Co-operative Party had been in an electoral pact with Labour and had seemed to many to be nothing more than a slightly quirky extra designation for many Labour MPs who wished to signal their commitment to the more bourgeois cooperative movement rather than their close ties to the trades unions, with the distinction being, at best, considered academic. However, this shift reflected both the general split within British centre-left politics (between a radical if bourgeois and bourgeois-adjacent politics and a more workerist trades unionist one) that harked back to the divides between Labour and Lloyd George’s New Liberals in the 1920s. It also spoke well of the success of the general centre-left project over the previous century and a half, with the ‘bourgeois’ designation no longer really referring to material conditions but speaking more to attitudes and taste. In this sense the revolt of the Co-operative MPs was a very Hanoverian-sounding rejection of the ‘Old Corruption’ of Labour and a hope to recreate something with, broadly, the same values but less of the brutal machine politics.

All of a sudden, a silence fell across the Parliament, like the calm before a shootout in a Western. Labour was wounded and, to continue the analogy, had taken a bullet to the side: they had lost their majority, now suffered from the stench of corruption and faced two parties (the Progressives and Umunna’s grouping, which at this stage was going by the name New Labour but which would formally go under the name the Co-operative Party from December 2025) that could challenge them on the centre-left and with swing voters. But, on the other hand, they were far from being out. The major unions had stuck with the party, the Liberals were still wheezing under a succession of leaders and the potential longevity of the Progressives and New Labour was still in doubt. The question was, would any of the opposition parties risk a motion of no confidence when an election, in this uncertain political moment, meant that they might be annihilated?

Last edited:

What name did Charles pick? George or Charles?

George VII

How did the Commonwealth and wider world react?

What’s the funeral operation like?

The monarchy, and Elizabeth II in particular, retains a similar level of support as OTL so the reaction was pretty big and effusive. I've not got exact details on what the funeral and public reaction would be like but I imagine a cross between OTL Princess Diana's death, Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and what it'll actually be like when she dies. The reaction is largely shared around the Commonwealth, where the monarchy remains generally as popular as in the UK.

Windows95

Banned

But wait... the tether is just a cable to launch though.... there's nothing that should be complicated about this.apparently it would be built out of a commercial material called spectra 2000 so its feasible to be built today, its just launch paradox that stops us, aka too expensive to launch too many things but not enough stuff to launch to make building a cheaper launch system viable you would need a government willing to make a leap of faith to build these stuff.

George VII

The monarchy, and Elizabeth II in particular, retains a similar level of support as OTL so the reaction was pretty big and effusive. I've not got exact details on what the funeral and public reaction would be like but I imagine a cross between OTL Princess Diana's death, Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and what it'll actually be like when she dies. The reaction is largely shared around the Commonwealth, where the monarchy remains generally as popular as in the UK.

I wrote about the death of the Queen here: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...bush-wins-92-tl.387760/page-255#post-17898316 You are welcome to crib. This might help: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_London_Bridge

Also burnt down Parliament in that thread. Major rebuild/refrub of the Houses of Parliament on the cards ITTL?

I wrote about the death of the Queen here: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...bush-wins-92-tl.387760/page-255#post-17898316 You are welcome to crib. This might help: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_London_Bridge

Yes, I was aware of Operation London Bridge (that Guardian article was probably the best thing that website has published for five years) and I imagine that will be the response TTL too. I was thinking more about the cultural and social response.

I'd not read your timeline before but it looks fun and will give it a look.

Also burnt down Parliament in that thread. Major rebuild/refrub of the Houses of Parliament on the cards ITTL?

No comment...

Miliband Ministry (2025-2026)

The Sound of Breaking Glass: Ed Miliband and the Last Gasp of Labour Hegemony

In the end, it was the Conservatives who made the move. Their new leader, Sir George Osborne, calculated that the party’s main challenge was to knock out the Libertarians as the main party of the British centre-right and gambled that attempting to force an election worked for them whichever way the vote went. If an election was called, the Conservatives would be in a better position to fight one than the Libertarians, who had spent the last few months in leadership crisis as the top troika of Kwasi Kwarteng, Priti Patel and Dominic Raab collapsed in civil war and donors began to migrate towards the Conservatives. On the other hand, even if the vote of no confidence didn’t go through, that would still give the Conservatives a cudgel with which to beat their Libertarian opponents.

The Libertarians and the Alliance joined with the Conservatives’ motion. After a delay of a day, the Liberals announced that they too would vote in favour of it. In truth, they did not particularly want another electoral fight, not trusting their ability to not keep on losing seats, but the leadership office of Rory Stewart recognised that, as the official Opposition, they had some kind of duty to support no confidence motions. There then followed a few more days of feverish speculation before Umunna confirmed that New Labour - now re-christened the Co-operative Party after the formal disaffiliation of that organisation from Labour - would also be voting for the motion. (The only question regarding the Co-operative’s movements would be whether they could afford to fight a new election - given the circumstances of the party’s birth there was little chance of them propping up Miliband’s government on a point of principle.)

This just left the Progressives’ position in doubt and Miliband immediately made moves to reach out to them both in public and private. Meetings between the two parties’ leadership teams proved productive. As has been observed previously, the Progressives’ former position as the leftmost wing of the Liberals, and their subsequent decade of existence as an independent party had seen them differ from Labour mainly in tone rather than policy, rejecting the more workerist policies of some of Labour’s machine, along with the nastiness that that machine had engendered. As such, there was a lot on the policy front that Miliband could offer to Progressive leader Jo Swinson. But, of course, she was inevitably going to ask for something in return and there was one thing that the Progressive shadow cabinet collectively agreed that they would demand: STV. Not a referendum on the issue (too many Progressives were refugees of the ‘Yes to STV’ campaign of 2013 to let that happen) but a bill passed through Parliament changing the voting system. Labour initially baulked at that and talks broke down. However, on the morning of the no confidence vote, Miliband picked up his phone.

At the vote, the Progressives waited until the other parties had filed into the division rooms and then walked with a gaggle of journalists following them from the chamber and into the Noe lobby.

Miliband’s negotiating had saved his premiership’s bacon but it immediately flung him into another legislative battle, this time over the passing of the electoral reform bill. A vigorous Labour whipping operation got most MPs on side but couldn’t prevent 85 from very publicly voicing their displeasure at being asked to vote for both a change to the electoral system without a manifesto mandate and one which only a decade previously many MPs had spent a good deal of political capital opposing. In the end, however, the bill passed into law in March as the Representation of the People Act 2026, on the back of Progressive and Labour loyalist votes, supplemented by the few Conservative MPs who still represented the party’s Mount-era radical spirit.

The next vote for the Westminster Parliament would be held under the single transferable vote system. Amidst the sense of party loyalties dissolving, it promised to be exciting, if nothing else.

But Miliband had been betrayed.

Only a month after the passing of the Act, the government lost a vote regarding changes to the funding for emergency hospitals (off the back of rebels from both Labour and the Progressives) and the Conservatives immediately put down another no confidence motion. Miliband and Chief Whip Sadiq Khan got to work bringing their own MPs in line and placed a call to Swinson’s team. But they got no response. They finally got Swinson on the phone early the next morning, where she confirmed that her team had decided that the Progressives would be voting for the Conservatives’ motion. Her citing of Labour’s alleged ‘betrayal’ of her party over Labour’s failure to support a Progressive amendment to a mental health bill was generally regarded as specious. In a rancorous atmosphere, Miliband’s government fell the following day and a general election was called for 23 July 2026.

As emerged later, Swinson’s betrayal of her agreement with Miliband caused him great emotional pain and he would reveal in his subsequent memoirs that he had suffered something close to a nervous breakdown that put him out of action for the first two weeks of the election campaign. Responsibility for Labour’s campaign devolved on Rachel Reeves and Sadiq Khan, both savvy politicians in their way but the absence of the Prime Minister was a gaping hole that persisted even after Miliband felt well enough to return to the campaign trail.

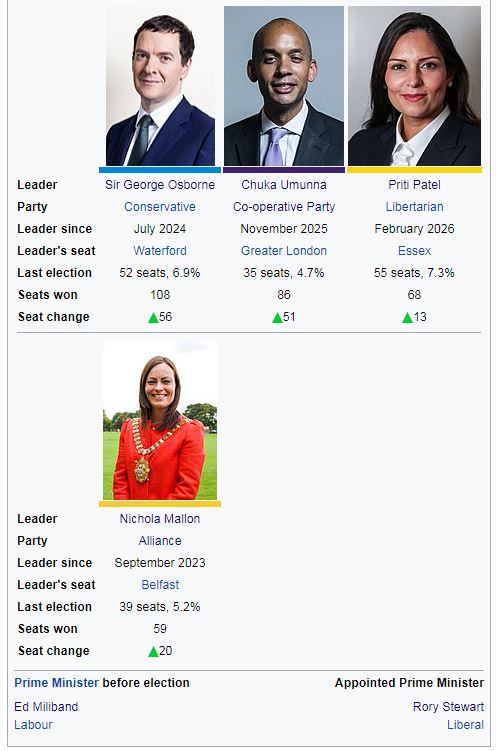

The results broke British politics. A combination of a new electoral system, a poor campaign by the government, economic stagnation and changing political trends resulted in the breaking of the Labour Party and the ending of a chapter in British political history. Labour remained the largest party in the Parliament but few people were really taken in by that. They lost more than half their MPs to crash to 172, their lowest total since 1921, and all of the Liberals, Progressives and the Conservatives each had more than 100 seats. Furthermore, the success of the Co-operatives, making gains of 51 to reach 86 seats, confirmed that Labour would be some way from having hegemonic control of the British centre and left for some time. Although the Libertarians also made gains of 13 seats, they were well behind the Conservatives and now clearly in second place in British right wing politics. The success of the Alliance Party, too, confirmed that the constitutional makeup of the United Kingdom would be a live political issue for the first time since the arguments over Irish Home Rule in the 1880s.

But, while the election clearly indicated the death of Labour Britain (or at least the beginning of it), it was unclear what was going to take its place. It was clear that Miliband was in no position to go on, either politically or, indeed, emotionally. The Labour leadership office, under the leadership of Sadiq Khan, put feelers out to the Progressives and the Alliance but it was clear that a majority could not be constructed just on that basis.

The linchpins of any deal would have to be the Liberals and the Co-Operatives and neither party, for their own reasons, had any interest in pursuing a path that would keep Labour in power. During talks that lasted three straight days, the Liberal and Co-Operative leadership came to an agreement that would install the Liberal leader, Rory Stewart as prime minister. Although they were more wary, the Progressives and the Alliance were willing to sign up to an agreement which gave them positions in the cabinet and a big say over policy direction.

Five days after the election, Stewart went to the Palace and received his commission. Afterwards, he stood on the steps of Downing Street and announced the formation of what he called a ‘Government of National Unity.’ A thoughtful man and well-known to the public following his activities in the African Wars, Stewart had been the subject of a ‘Draft Stewart’ campaign by all of Labour, the Liberals, the Progressives and the Conservatives in the early 2020s before he finally entered Parliament in the 2023 election as Liberal constituency MP. His elevation to the leadership only five months later was considered, at the time, to have been a symptom of Liberal weakness but he had proven a competent manager of his fractious parliamentarians and a strong campaigner. His personal charm was considered a vital glue that would knit together the disparate parts of his government, in a premiership that would ultimately be dominated by constitutional and Commonwealth affairs.

In the end, it was the Conservatives who made the move. Their new leader, Sir George Osborne, calculated that the party’s main challenge was to knock out the Libertarians as the main party of the British centre-right and gambled that attempting to force an election worked for them whichever way the vote went. If an election was called, the Conservatives would be in a better position to fight one than the Libertarians, who had spent the last few months in leadership crisis as the top troika of Kwasi Kwarteng, Priti Patel and Dominic Raab collapsed in civil war and donors began to migrate towards the Conservatives. On the other hand, even if the vote of no confidence didn’t go through, that would still give the Conservatives a cudgel with which to beat their Libertarian opponents.

The Libertarians and the Alliance joined with the Conservatives’ motion. After a delay of a day, the Liberals announced that they too would vote in favour of it. In truth, they did not particularly want another electoral fight, not trusting their ability to not keep on losing seats, but the leadership office of Rory Stewart recognised that, as the official Opposition, they had some kind of duty to support no confidence motions. There then followed a few more days of feverish speculation before Umunna confirmed that New Labour - now re-christened the Co-operative Party after the formal disaffiliation of that organisation from Labour - would also be voting for the motion. (The only question regarding the Co-operative’s movements would be whether they could afford to fight a new election - given the circumstances of the party’s birth there was little chance of them propping up Miliband’s government on a point of principle.)

This just left the Progressives’ position in doubt and Miliband immediately made moves to reach out to them both in public and private. Meetings between the two parties’ leadership teams proved productive. As has been observed previously, the Progressives’ former position as the leftmost wing of the Liberals, and their subsequent decade of existence as an independent party had seen them differ from Labour mainly in tone rather than policy, rejecting the more workerist policies of some of Labour’s machine, along with the nastiness that that machine had engendered. As such, there was a lot on the policy front that Miliband could offer to Progressive leader Jo Swinson. But, of course, she was inevitably going to ask for something in return and there was one thing that the Progressive shadow cabinet collectively agreed that they would demand: STV. Not a referendum on the issue (too many Progressives were refugees of the ‘Yes to STV’ campaign of 2013 to let that happen) but a bill passed through Parliament changing the voting system. Labour initially baulked at that and talks broke down. However, on the morning of the no confidence vote, Miliband picked up his phone.

At the vote, the Progressives waited until the other parties had filed into the division rooms and then walked with a gaggle of journalists following them from the chamber and into the Noe lobby.

Miliband’s negotiating had saved his premiership’s bacon but it immediately flung him into another legislative battle, this time over the passing of the electoral reform bill. A vigorous Labour whipping operation got most MPs on side but couldn’t prevent 85 from very publicly voicing their displeasure at being asked to vote for both a change to the electoral system without a manifesto mandate and one which only a decade previously many MPs had spent a good deal of political capital opposing. In the end, however, the bill passed into law in March as the Representation of the People Act 2026, on the back of Progressive and Labour loyalist votes, supplemented by the few Conservative MPs who still represented the party’s Mount-era radical spirit.

The next vote for the Westminster Parliament would be held under the single transferable vote system. Amidst the sense of party loyalties dissolving, it promised to be exciting, if nothing else.

But Miliband had been betrayed.

Only a month after the passing of the Act, the government lost a vote regarding changes to the funding for emergency hospitals (off the back of rebels from both Labour and the Progressives) and the Conservatives immediately put down another no confidence motion. Miliband and Chief Whip Sadiq Khan got to work bringing their own MPs in line and placed a call to Swinson’s team. But they got no response. They finally got Swinson on the phone early the next morning, where she confirmed that her team had decided that the Progressives would be voting for the Conservatives’ motion. Her citing of Labour’s alleged ‘betrayal’ of her party over Labour’s failure to support a Progressive amendment to a mental health bill was generally regarded as specious. In a rancorous atmosphere, Miliband’s government fell the following day and a general election was called for 23 July 2026.

As emerged later, Swinson’s betrayal of her agreement with Miliband caused him great emotional pain and he would reveal in his subsequent memoirs that he had suffered something close to a nervous breakdown that put him out of action for the first two weeks of the election campaign. Responsibility for Labour’s campaign devolved on Rachel Reeves and Sadiq Khan, both savvy politicians in their way but the absence of the Prime Minister was a gaping hole that persisted even after Miliband felt well enough to return to the campaign trail.

The results broke British politics. A combination of a new electoral system, a poor campaign by the government, economic stagnation and changing political trends resulted in the breaking of the Labour Party and the ending of a chapter in British political history. Labour remained the largest party in the Parliament but few people were really taken in by that. They lost more than half their MPs to crash to 172, their lowest total since 1921, and all of the Liberals, Progressives and the Conservatives each had more than 100 seats. Furthermore, the success of the Co-operatives, making gains of 51 to reach 86 seats, confirmed that Labour would be some way from having hegemonic control of the British centre and left for some time. Although the Libertarians also made gains of 13 seats, they were well behind the Conservatives and now clearly in second place in British right wing politics. The success of the Alliance Party, too, confirmed that the constitutional makeup of the United Kingdom would be a live political issue for the first time since the arguments over Irish Home Rule in the 1880s.

But, while the election clearly indicated the death of Labour Britain (or at least the beginning of it), it was unclear what was going to take its place. It was clear that Miliband was in no position to go on, either politically or, indeed, emotionally. The Labour leadership office, under the leadership of Sadiq Khan, put feelers out to the Progressives and the Alliance but it was clear that a majority could not be constructed just on that basis.

The linchpins of any deal would have to be the Liberals and the Co-Operatives and neither party, for their own reasons, had any interest in pursuing a path that would keep Labour in power. During talks that lasted three straight days, the Liberal and Co-Operative leadership came to an agreement that would install the Liberal leader, Rory Stewart as prime minister. Although they were more wary, the Progressives and the Alliance were willing to sign up to an agreement which gave them positions in the cabinet and a big say over policy direction.

Five days after the election, Stewart went to the Palace and received his commission. Afterwards, he stood on the steps of Downing Street and announced the formation of what he called a ‘Government of National Unity.’ A thoughtful man and well-known to the public following his activities in the African Wars, Stewart had been the subject of a ‘Draft Stewart’ campaign by all of Labour, the Liberals, the Progressives and the Conservatives in the early 2020s before he finally entered Parliament in the 2023 election as Liberal constituency MP. His elevation to the leadership only five months later was considered, at the time, to have been a symptom of Liberal weakness but he had proven a competent manager of his fractious parliamentarians and a strong campaigner. His personal charm was considered a vital glue that would knit together the disparate parts of his government, in a premiership that would ultimately be dominated by constitutional and Commonwealth affairs.

Labour suffers a Co-LAPse (Co-Operative, Liberal, Alliance, Progressive) in their vote share.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Share: