It's because I used a map from HOI4 and than edited itI only fixed the Atlantic discrepancy, not any borders.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Place In the Sun: What If Italy Joined the Central Powers? (1.0)

- Thread starter Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

- Start date

I'm fixing Serbia but as far as I know Kars remained Russian. The Ottoman went back to the 1914 border.

Also, some other clarification if possible:

1)What does "Montenegro is a civilian part of the Austrian portion of the empire" mean? Is it annexed or not?

2)What is the border between A-H and Serbia? The 1914 border or something else?

1: It's annexed, and is as Austrian as Vienna

2: The Austro-Serbian border is the 1914 one

Also, Kars is Russian

Does anyone have any ideas as to how this might impact the 1916 election? Who would you rather see win and why?

Ficboy

Banned

Well since the United States never enters World War I it might go in Wilson's favor given his popularity.Does anyone have any ideas as to how this might impact the 1916 election? Who would you rather see win and why?

The American non-entry into the Great War won't change much, since the USA didn't enter until 1917 in OTL.Well since the United States never enters World War I it might go in Wilson's favor given his popularity.

His slogan of "He kept us out of war" implied that he would continue to do so, and now, it's a non-issue; the war is over. There might be people voting on that issue out of thanks that he did, but not out of fear that the other party will get us into the war.

bguy

Donor

Does anyone have any ideas as to how this might impact the 1916 election? Who would you rather see win and why?

I think the war ending in 1916 would hurt Wilson for three reasons.

1) There's bound to be an economic downturn in the US as a result of the end of the war which will inevitably hurt the party in power.

2) IOTL Teddy Roosevelt's belligerence during the 1916 campaign season is believed to have hurt the Hughes campaign since it frightened people into thinking that a vote for Hughes was a vote for war. That won't be an issue if the war is already over; and

3) Japan seizing French Indochina is going to freak out voters in California (where there was a ton of anti-Japanese sentiment at this time.) Given how close the 1916 vote was in California IOTL that should be enough flip that key state to the GOP.

Dear readers,

Bad news.

I simply can't decide between Wilson or Hughes, Mexican War or not, etcetera. I've gone through a number of revisions and drafts (check out one in my test thread if you fancy), but can't get the chapter where I want it.

I love this TL and putting out high-quality work for you means something to me; I really don't want to turn out a half-baked product just to "get on with it".

The USA chapter will be posted in a few days, but no promises as to when. I'm sorry.

- Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

Bad news.

I simply can't decide between Wilson or Hughes, Mexican War or not, etcetera. I've gone through a number of revisions and drafts (check out one in my test thread if you fancy), but can't get the chapter where I want it.

I love this TL and putting out high-quality work for you means something to me; I really don't want to turn out a half-baked product just to "get on with it".

The USA chapter will be posted in a few days, but no promises as to when. I'm sorry.

- Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

Ficboy

Banned

Just focus on Wilson vs Hughes then the Second Mexican-American War.Dear readers,

Bad news.

I simply can't decide between Wilson or Hughes, Mexican War or not, etcetera. I've gone through a number of revisions and drafts (check out one in my test thread if you fancy), but can't get the chapter where I want it.

I love this TL and putting out high-quality work for you means something to me; I really don't want to turn out a half-baked product just to "get on with it".

The USA chapter will be posted in a few days, but no promises as to when. I'm sorry.

- Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

Take your time. Depending on the election, it could even be thrown to the house for more fun. EDIT: Since there's an odd number of electoral votes, one elector has to do something strange to create a tie, like vote for someone else, or drop dead.

THIS could be a big help!

www.270towin.com

You can change any state back and forth freely, and let the map do the computing for you. (I'm using it myself a LOT as I prepare for Reagan vs Carter!)

www.270towin.com

You can change any state back and forth freely, and let the map do the computing for you. (I'm using it myself a LOT as I prepare for Reagan vs Carter!)

EDIT II: Wilson could also be assassinated, and nothing of value would be lost.

THIS could be a big help!

1916 Presidential Election Interactive Map - 270toWin

Create an alternate history with this 1916 interactive electoral map. Develop your own what-if scenarios. Change the president, the states won and the nominees.

www.270towin.com

www.270towin.com

EDIT II: Wilson could also be assassinated, and nothing of value would be lost.

Last edited:

bguy

Donor

Someone brought it up earlier, but what's going on with Mexico? Obviously there's no Zimmerman telegram, but Germany doing much better could maybe butterfly away the occupation of Veracruz (since the US was so paranoid they confused a shipment of weapons for President Huerta as coming from Germany). That could potentially help Huerta stay in power longer, since the occupation was one of causes of his fall, and that keeps the Carranza/Villa/Zapata alliance together longer as well, changing how the war plays out

The occupation of Veracruz began on April 21, 1914, so I think it predates the POD.

As for the possibility of a war between the U.S. and Mexico, Wilson was pretty adamant against it for reasons beyond just not wanting to get distracted when faced with the possibility of war in Europe. From Woodrow Wilson A Biography by John Milton Cooper, Jr.:

"On May 11, after the raid in Texas and the ensuing war scare, he talked off the record with the journalist Ray Stannard Baker, who noted, "He said his Mexican policy was based upon two of the most deeply seated convictions of his life: first his shame as an American over the first Mexican war & his resolution that while he was president there should be no such predatory war; Second upon his belief... that a people had the right 'to do as they damned pleased with their own affairs.'"

The same book also says that Wilson told Baker he was ashamed over the rule the US had played in overthrowing President Madero and thought intervention in Mexico was being pushed by American business interests "who wanted the oil & metals of Mexico & were seeking intervention to get them." It also notes that Wilson's campaign material mentioned him avoiding war with Mexico more often than him avoiding the war in Europe.

Thus with Wilson morally opposed to the idea of a predatory war with Mexico and with having avoided such a war being a key part of his reelection campaign I think the likelihood of such a war is pretty low.

Wilson's moral opposition holds as much weight as a piece of paper. For someone who supposedly believed that people had the right to do as they pleased with their affairs, he certainly didn't hesitate throwing his weight around in Central America.

*spits*

Here's to hoping he loses the election, followed by a string of catastrophes that leaves him a modern day Job. He deserves nothing less.

No, that's still too dignified an end for him, with a greater place in the history books than he deserves. Something more...ignominous, should be his fate. Falling down the stairs, maybe. Getting run over by a horse. Or a car. Maybe he fell off a ship and drowned in the sea.

*spits*

Here's to hoping he loses the election, followed by a string of catastrophes that leaves him a modern day Job. He deserves nothing less.

EDIT II: Wilson could also be assassinated, and nothing of value would be lost.

No, that's still too dignified an end for him, with a greater place in the history books than he deserves. Something more...ignominous, should be his fate. Falling down the stairs, maybe. Getting run over by a horse. Or a car. Maybe he fell off a ship and drowned in the sea.

Nevertheless he let Pershings invasion in 1916 happen ... which - IMHO - without too much changes OTL could have evolved into something still bigger.....

Thus with Wilson morally opposed to the idea of a predatory war with Mexico and with having avoided such a war being a key part of his reelection campaign I think the likelihood of such a war is pretty low.

Should perhaps not be forgotten that the Carranza-goverment was not realy controlling all (even largest part ??) of Mexico.

Ficboy

Banned

Let's not be too harsh towards Woodrow Wilson. I'm no apologist of Wilson and I know he wasn't perfect his racial attitudes notwithstanding though then again almost everybody who was white shared similar views but he also fought for the rights of workers, enforced antitrust legislation, passed strong protective tariffs, appointed the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, endorsed women's suffrage, tried to bring world peace via self determination and at least spoke out against lynching in spite of his beliefs on race.Wilson's moral opposition holds as much weight as a piece of paper. For someone who supposedly believed that people had the right to do as they pleased with their affairs, he certainly didn't hesitate throwing his weight around in Central America.

*spits*

Here's to hoping he loses the election, followed by a string of catastrophes that leaves him a modern day Job. He deserves nothing less.

No, that's still too dignified an end for him, with a greater place in the history books than he deserves. Something more...ignominous, should be his fate. Falling down the stairs, maybe. Getting run over by a horse. Or a car. Maybe he fell off a ship and drowned in the sea.

Last edited:

I honestly expect Hughes to win. The hawks will be vindicated, and I think there will be angst over “losing Europe.” Progressive isolationists won’t be as motivated to turn out, and it was close anyway. I also think it allows for a more interesting TL, with the Dems likely in control in the 20s until the alt-Great Depression, as the winner of 1916, especially here, is going to lose in 1920 due to war debts coming due and causing severe economic problems in 1918-1920. I also think Hughes could have some very interesting policies, and you might even get an alt-LoN done with him in. I doubt Wilson could get the LoN or similar passed, while Hughes’s strength in the party plus being willing to accommodate the reservationists should get something done. That could also be very interesting in the lead-up to WW2, and it might lead to German-American-British rapprochement.

I honestly expect Hughes to win. The hawks will be vindicated, and I think there will be angst over “losing Europe.” Progressive isolationists won’t be as motivated to turn out, and it was close anyway. I also think it allows for a more interesting TL, with the Dems likely in control in the 20s until the alt-Great Depression, as the winner of 1916, especially here, is going to lose in 1920 due to war debts coming due and causing severe economic problems in 1918-1920. I also think Hughes could have some very interesting policies, and you might even get an alt-LoN done with him in. I doubt Wilson could get the LoN or similar passed, while Hughes’s strength in the party plus being willing to accommodate the reservationists should get something done. That could also be very interesting in the lead-up to WW2, and it might lead to German-American-British rapprochement.

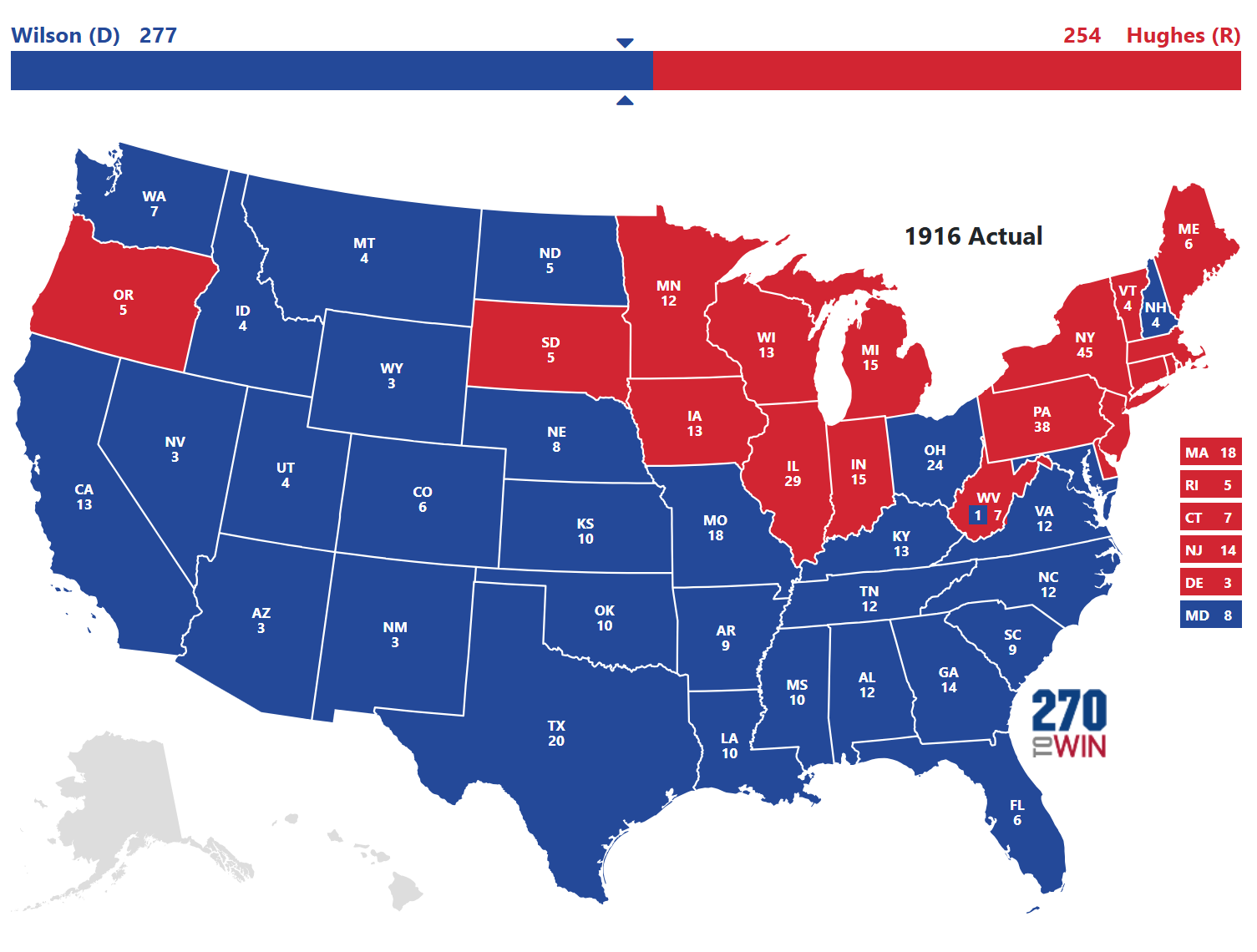

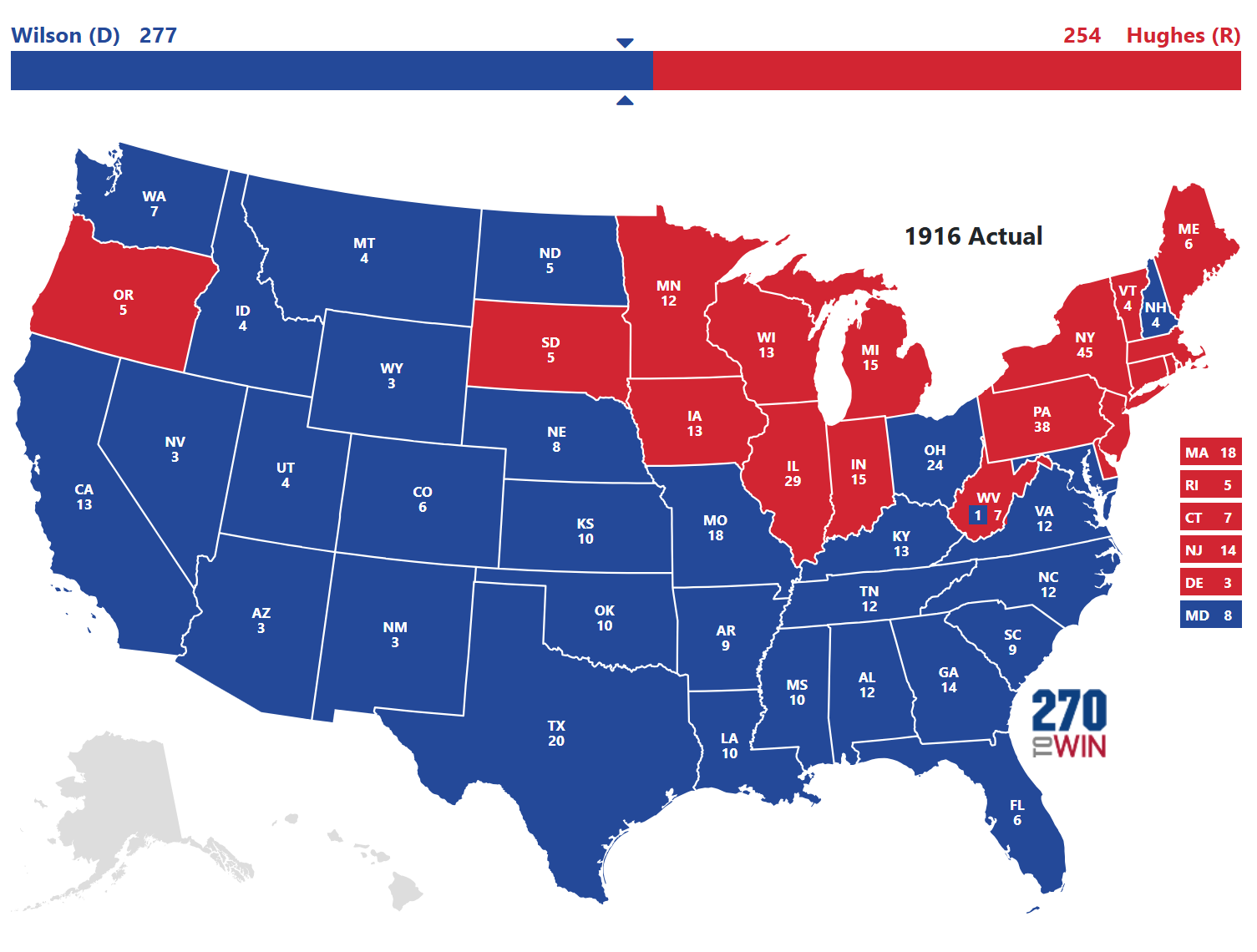

I think Hughes should take it here. Yeah, the 1916 elections were close (Wilson won 277-254, 266 needed to win) so I could see a few states that could've flipped Hughes direction, given how some of the votes went. In particular, California was decided to Wilson by about 3800 votes. Had Hughes won California, he'd win the election (267-264 in Hughes favor)

bguy

Donor

Nevertheless he let Pershings invasion in 1916 happen ... which - IMHO - without too much changes OTL could have evolved into something still bigger.

Should perhaps not be forgotten that the Carranza-goverment was not realy controlling all (even largest part ??) of Mexico.

That's true but Villa deliberately avoided confronting US troops during Pershing's expedition. (Villa wanted the US forces in northern Mexico because their presence made Carranza look weak to the Mexican people while also driving a wedge between the US and Carranza.) There's little reason for Villa to change that policy since it proved extremely effective IOTL. (His number of followers greatly increased during the US expedition.)

And of course US and Mexican government forces did fight during the expedition (most notably in the Battle of Carrizal) without it escalating into a larger conflict because neither Wilson nor Carranza wanted war. (Wilson's reaction to Carrizal was to order Pershing not to advance any further into Mexico.) If Carrizal (which saw dozens of casualties on both sides) wasn't enough to provoke either side to war then its hard to imagine either Wilson or Carranza letting any one incident push them into a war that neither wanted.

Last edited:

Yeah I corrected myself in a follow up post. I mixed that event with Huerta trying to return in 1915.The occupation of Veracruz began on April 21, 1914, so I think it predates the POD.

As for the possibility of a war between the U.S. and Mexico, Wilson was pretty adamant against it for reasons beyond just not wanting to get distracted when faced with the possibility of war in Europe. From Woodrow Wilson A Biography by John Milton Cooper, Jr.:

"On May 11, after the raid in Texas and the ensuing war scare, he talked off the record with the journalist Ray Stannard Baker, who noted, "He said his Mexican policy was based upon two of the most deeply seated convictions of his life: first his shame as an American over the first Mexican war & his resolution that while he was president there should be no such predatory war; Second upon his belief... that a people had the right 'to do as they damned pleased with their own affairs.'"

The same book also says that Wilson told Baker he was ashamed over the rule the US had played in overthrowing President Madero and thought intervention in Mexico was being pushed by American business interests "who wanted the oil & metals of Mexico & were seeking intervention to get them." It also notes that Wilson's campaign material mentioned him avoiding war with Mexico more often than him avoiding the war in Europe.

Thus with Wilson morally opposed to the idea of a predatory war with Mexico and with having avoided such a war being a key part of his reelection campaign I think the likelihood of such a war is pretty low.

The USA will be posted tomorrow!

(I had the day off, so I spent it planning and writing!)

After that, it's over to Austria-Hungary

(I had the day off, so I spent it planning and writing!)

After that, it's over to Austria-Hungary

Chapter 15- The US 1916 Election

Chapter Fifteen- The 1916 US Election

"I tell you, if the perfidious British do not honour their end of the deal, this country will see its worst panic in years. And I, the generous president acting in his people's interest, will be blamed. But if the economy can hold out till the eighth, I shall be saved. It all comes down to twenty-four hours, I tell you..."

-President Woodrow Wilson, in a private remark shortly before the election.

"For most of the night, I felt I was doomed. I contemplated going back to my practice in New York, or to retiring and writing my memoirs. Just another failed Presidential candidate! But at the eleventh hour, the Lord delivered California, Oregon, and Washington into my lap. And I was saved."

-Charles Evans Hughes commenting on his close-run victory in the 1916 election in his memoirs The Twenty-Ninth Torchbearer.

The French army mutinies, the September Revolution, the treaties of Dresden and Konigsberg, and the Japanese land grab in Indochina shook the world. Germans cheered, Britons mourned, Frenchmen kept their heads down, and Japanese gloated. Yet, for the United States of America, the tumultuous events of 1916 might’ve been an entertaining football match in the papers- it was all very interesting, but nothing to really get excited over.

America was an ocean away from the events of the Great War. Individual Americans had signed up for the French Foreign Legion and similar units, while some had offered their medical services behind the lines. Aside from that, America had sat contentedly on the sidelines. Woodrow Wilson had declared that the United States was “too proud to fight”, which suited everyone fine. Isolationism had been the order of the day since George Washington, and your average Yank not only hadn’t ever heard of Verdun before the fighting started, he couldn’t have cared less about it. Irish Americans loathed the British Empire with passionate fury, while the descendants of German immigrants in the Dakotas unabashedly rooted for the Central Powers. On the other hand, Americans of British, Russian, and French descent threw their support behind the Entente. Getting the disparate peoples of the USA to line up on either side would’ve been an impossible task, and Wilson was grateful that he didn’t have to manage it.

Despite its neutrality, the United States was a key player in the Great War- albeit one whose contributions are often overlooked. Without American financial aid, it is doubtful that the Entente could’ve held out as long as they did. After President Wilson had permitted loans to the belligerents, $2 billion had made its way into British pockets. Britain’s defeat threw American bankers into a fuss, as they wondered if they’d ever see that money again. Throughout the summer of 1916, they made clear to the British government that they would need their money back on the agreed-to schedule. However, Britain was in exactly the same predicament- they had loaned millions to the French and Russians. France was coming apart at the seams and Tsar Michael’s regime desperately trying to stay afloat, meaning London wouldn’t see a penny from either. To make matters worse, the pound was steadily devaluing as compared to the dollar. It wasn’t anything like the inflation the French were seeing (which would’ve been almost amusing if it weren’t true), but it would impact Britain’s ability to pay. And all this ignores the monumental amount being spent feeding and equipping the BEF. Before being turfed out of office, Herbert Asquith had commented that “Washington’s financiers may yet prove a bigger foe than the Kaiser is now”, and that summed up many people’s fears. After coming into power, David Lloyd George took one look at the UK’s books and said that he had no confidence in the UK’s ability to pay the debt back for years; the Chancellor of the Exchequer agreed with him.

Members of the Anglo-French Financial Commission leaving a meeting on 24 October 1916, looking quite downcast.

It was decided to call a session of the Anglo-French Financial Commission to explain the situation to the Americans. The Commission had been founded in 1915 to negotiate loans from the great American banker JP Morgan, and had secured half a billion dollars in September of that year. Now, it was time to pay the piper. They conferred on the 24th of October in London, where the ashen-faced French announced that they were flat broke. The reparations to Germany would keep them busy for the remainder of the century while driving the value of the franc into the ground- one commentator said that the franc’s value was already so low, “it was now pushing up daisies.” With the colonies veering on the edge of revolt (1) and the fabric of la Nation unravelling, paying off the debt to the Americans was literally the last thing they could afford. The British response was scarcely more encouraging. Most of the UK’s loans from the Americans had been backed up by collateral, so London was considering defaulting and letting the Americans take the collateral instead. With the British economy being harmed by demobilisation, old trading patterns a casualty of the war, and the pound steadily sinking, paying the Americans in cash seemed desperately unwise. When, after two days, the commission telephoned JP Morgan with the bad news, the American banker went ashen-faced and downed a double whiskey. This would be a setback for his firm, no two ways about it, but there was nothing he could do now. Morgan informed the Commission that he would be in touch with the President before going off to telephone Wilson.

For President Wilson, the news couldn’t have come at a worse time. Election day would be along in less than two weeks, and the polls all favoured his opponent Charles Evans Hughes. If Wall Street started getting jittery now, it would be all over. Thus, after a confidential meeting with the Secretary of the Treasury, the President decided to keep the story out of the papers as much as possible. If he could just kick the can down the road for a month, he’d be fine. Wilson’s diary for the twenty-seventh of October says that “if the big boys on Wall Street lose their strength and falter before November the seventh, I am doomed. If they fall over dead on the eighth, I shall manage well enough.” It was a cynical attitude, but understandable. The President instructed Morgan to issue an ultimatum to the Commission in his name immediately: either commit to paying off all debt by the originally agreed dates, or he would treat them as having defaulted. The Commission replied within four hours: they were going to default and risk the consequences.

The next day, Friday the 27th, President Wilson issued an executive order allowing JP Morgan to assume control over all British-and-French-held assets in the United States. Enterprises as diverse as railroads, shipping yards, coal mines, and factories now found themselves under new ownership. No one knew all the details in the first 24 hours, which meant that the stock market had a bad day. But worse was the fact that not all these companies wanted to come under Morgan’s ownership. The last few days in October saw “incidents”, where managers of Anglo-French companies, born in the motherland, became bitter over losing their positions to the greedy Americans, who hadn’t even fought in the war, and who hadn’t had to agonise over relatives back home overrun by les Boches. They gave vent to their anger by doing things like leaving equipment in an unfit state and laying off employees. Not every asset suffered such problems and, contrary to what many thought there was no widespread conspiracy involved, but the overall effect was to infuriate Morgan. In a livid telephone call to the Anglo-French Finance Commision on 1 November, he said that because of these acts of sabotage, he would only value the collateral at three-fourths its official value, as that was the most he could hope to get out of it. Britain and France were still on the hook for a quarter of their debts, and Morgan wouldn’t settle for anything less than cash. If they didn’t think he was serious, they were welcome to talk to President Wilson.

When Wilson found out about the sabotage, he was livid. Britain and France, he thundered, were cheaters taking advantage of American goodwill! He vowed that never again would they see a penny of America’s money. However, he had more urgent things to worry about. The past four days had been volatile ones for the stock market, and the American public was coming to realise that something was wrong with the economy. For Wilson, the most important thing was to stave off substantial damage for another week, until the election. Therefore, he telephoned Morgan on the afternoon of the first with a cheery message: if the firm looked likely to collapse- God forbid- Wilson would prop them up. That done, he held an impromptu press conference where he declared his “total faith in the good health and prosperity of the American economy.” There was little more he could do.

7 November 1916 was the big day. The stock market was topsy-turvy, but that had been true for the past week, and no one paid it too much heed. Workers took the morning off and trudged to the polls, while capitalists had their chauffeurs drive them. The day crawled by on hands and knees for the President, who spent most of it anxiously pacing his office, his wife Edith consoling him and bringing him cups of coffee. Wilson telephoned Wall Street four times that day, demanding to know how the stock market was doing. It was fine, replied the frustrated operator, no worse than before. But nothing could soothe the US President’s nerves. He sat at his desk all night, watching the results come in. The South was a foregone conclusion: it had been a Democratic bastion since before the Civil War, and Wilson was a southerner himself. However, Hughes slaughtered him in the Northeast, winning all of New England plus Pennsylvania and his home state of New York. Meanwhile, electors in West Virginia delivered seven of the state’s votes to Hughes and only one to Wilson. As the night rolled on, Hughes was leading Wilson by almost fifty electoral votes. It was essential that Wilson win ground in the Midwest if he wanted to walk away triumphant. Things started out on the right foot, with Ohio dropping 24 electoral votes into the President’s lap. To no one’s surprise, the Central Time states of the former Confederacy went Wilson’s way. He received an unexpected boost when Wisconsin and the Dakotas dropped into his lap after a hard-fought race. (2) Despite Hughes’ winning the rest of the Midwest, the Central Time states had come through for Wilson, who now held a six-point lead. With only fifty-five electoral votes left unclaimed, victory would clearly be razor-thin. As results from the Mountain Time states started coming in, Wilson was jubilant. Utah, Colorado, Montana, Arizona, and New Mexico all went his way, while Hughes gained a paltry seven votes from Idaho and Wyoming. With only four states left, it looked as though Wilson would be set for another four years. As Nevada swung his way, the US President pondered when his opponent would call to concede… surely, it couldn’t be long now? Edith was going to be so proud!

Then the trouble started.

The West Coast had always had a rather leery view of the Japanese. Japanese immigrants were very visible in society, and many whites distrusted them. Japanese belligerence in the Pacific frightened many, and there was a great deal of displeasure at the Wilson administration over agricultural policy and the struggling economy. Oregon was the first to drop into Hughes’ lap, narrowing the electoral college gap to seventeen votes. Wilson would have to win one of the two states, but surely that wouldn’t be too hard. Yet, before the President’s horrified eyes, reports drifting back from California and Washington declared that Hughes had a slim but substantial majority in both states. Finally, a little before two AM, both declared for the Republicans. Woodrow Wilson telephoned President-elect Charles Evans Hughes to concede; having lost 264-267. Congress also tilted steadily Republican (3), giving the GOP a majority in both houses.

Charles Evans Hughes: the 29th President of the United States

The bottom fell out of the economy six days later.

On 11 November- the day the Treaty of Konigsberg was signed- President Wilson announced that since Britain and France had refused to commit to paying off their debts, he was issuing an executive order transferring some $500 million in federal money to cover JP Morgan’s losses. Everyone from economists to Constitutional lawyers howled about this, but Wilson was adamant- after all, it wasn’t as if popular opinion mattered much to him anymore. He left a nice little present for President-elect Hughes by withdrawing the money from funds earmarked for the 1917 budget, which would earn him plenty of scorn- the phrase “robbing Sam to pay Jack” (Uncle Sam to JP “Jack” Morgan) (4) would become commonly used in the Northeast in the 1920s. The news that the biggest bank in the US was in trouble triggered a panic on Wall Street, and starting on the 13th, investors began deserting Morgan. Ironically, the firm was in reasonably solid shape and could’ve weathered the storm, but the public didn’t know that. People began selling their Morgan stocks… and the rot spread from there. By Thanksgiving Day, the US economy had reverted to its meagre 1913 state- the collapse of the arms industry, which had made good money selling to the Entente, only exacerbated the problem. By the time the transfer of power came on 4 March 1917, Wilson’s popularity was in the lower forties, and historians rank him as one of the worst presidents of the United States.

Charles Evans Hughes had a long and varied career. As Governor of New York State, he had implemented many progressive reforms while never fully throwing his weight behind the cause. During the Great War, he had advocated greater American military preparedness, and the German victory had dissapointed him. In his inaugural address, Hughes promised to fix the economy and, looking directly at Wilson, “to further the bonds of equality between the disparate peoples of our nation.” Hughes’ first step was to undo many of Wilson’s financial policies. While he lacked the desire- to say nothing of the authority- to gut the Sixteenth Amendment, he scaled back the powers of the Federal Reserve and cut back the money supply to produce deflation. These efforts were widely publicised, and the Secretary of the Treasury called on investors to calmly return to the stock market. President Hughes appointed Herbert Hoover as the chairman of a new Bureau of Foreign Reconstruction, something applauded by many Progressives. Hoover would subsequently direct relief operations in France and send supplies to the German-occupied parts of Western Europe; manfacturing such supplies in the United States helped revive the job market. Recovery was slow, but by 1919 the recession was over, with the Federal Reserve Bank’s powers gutted and federal income tax minimised. (5)

Hughes also developed a reputation as hostile to big business, believing- not unjustly- that Woodrow Wilson’s grant to JP Morgan had stolen $500 million from his administration. He was determined to get the federal government’s money back without going down the path of raising federal taxes, which would’ve contradicted his own economic policy. Thus, his administration took JP Morgan to court in spring 1917. The sheer gall of this raised plenty of eyebrows and won Hughes much scorn, but he was oblivious. When it came to the federal government versus one of the biggest banks in the world, there was genuine debate as to who would win. The US government, represented by Attorney General Thomas W. Gregory (6) charged that Woodrow Wilson had violated American budgetary law by transferring money earmarked for another Administration without Hughes’ consent, and called for JP Morgan to return that $500 million to the US government. The bank retorted that it was none of the current Administration’s business what its predecessor had done, and that it had done nothing wrong in accepting that money. The case reached all the way to the Supreme Court, where it nearly tied- Chief Justice E.D. White was the deciding vote. As a Democrat and Confederate veteran, everyone expected White to back Wilson’s action. However, he was also a proponent of anti-trust laws and had never been keen on Morgan’s power. Thus, he ruled that yes, Wilson had violated the law in transferring $500 million which didn’t belong to him to Morgan, and that the bank was obligated to give it up. This earned both President Hughes and Chief Justice White the unending hatred of corporate power and Southern Democrats, and the two men became unlikely bedfellows. Woodrow Wilson, fearful that he might face charges, considered decamping for Canada or the Bahamas, but President Hughes decided not to go after his predecessor- he knew he had done well getting his way here and didn’t want to push it… plus, a US President prosecuting his predecessor would set an ominous precedent. United States v JP Morgan would become a standard weapon in the Progressive arsenal and help to set a precedent that no one was above legal power.

Hughes was also committed to being the antithesis of Wilson with regards to racial matters. A New Yorker, he had a thoroughly Yankee view of race relations, and his time as a judge had seen him rule in favour of African-Americans time and again. The Southern Democrats in Congress, who still held enough power to make him work with them, hampered his efforts time and again. They loathed him for defeating Wilson in the election and implicitly attacking him in United States v JP Morgan, and they would never accept federal desegregation laws. Thus, much of what Hughes wanted to do would have to wait decades, but he was able to use his presidential power to accomplish some things. In the summer of 1917, fresh from his victory in United States v JP Morgan, Hughes signed executive orders integrating and forbidding racial discrimination in the military. This earned him the acclaim of Booker T. Washington and the NAACP, and even today Hughes is well-remembered for his civil rights stance. And he would have time to use his new, integrated military, as the United States was about to be thrown into a war…

Mexico had been in turmoil for nearly seven years when President Hughes took office. After strongman Porforio Diaz was overthrown in 1911, chaos had followed until Venustiano Carranza had come up on top. By October 1915, Carranza had achieved American recognition and controlled much of Mexico. However, from his base in northern Chihuahua, the warlord Pancho Villa continued to hold out, and had made several incursions into American territory for supplies. This was unacceptable for Hughes, who ordered General John Pershing across the border to hunt down Villa and bring him to justice. Pershing’s mission was a failure- the warlord evaded capture, while President Carranza did not appreciate the unasked-for intervention and ordered the Americans out, before proclaiming a new, nationalist constitution in February 1917. The United States, hegemonic giant that it was, was not used to being treated this way, and a furious Hughes declared that America would not stand for this.

A poster commemorating General "Blackjack" Pershing's Second Punitive Expedition of August 1917.

During the Great War, as mentioned above, Hughes had advocated a much firmer American stance on the Entente side. He believed strongly that only military might could keep America a Great Power, and a snub from a small country such as Mexico would not be tolerated. In August 1917, he ordered Pershing to lead a second expedition into Chihuahua to bring back Pancho Villa, dead or alive. Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico all called up their National Guard units, just in case. Hughes didn’t want war with Carranza, but he had to defend American prestige at any cost. Pershing crossed the border on 2 August and immediately ran into central government troops. They declared that tracking down Villa was the responsibility of the Mexican government, not the United States, and offered to “escort” Pershing back to the US border. The American general informed the Mexican commander that his orders were to capture or kill Villa, and that nothing would stop him. Shots broke out a few moments later, and from that moment American and Mexican troops were locked in combat. By the end of the day, six Americans and thirteen Mexicans lay dead on the dry soil of Chihuahua, and no one knew what to do next. Pershing ordered his men to entrench and sent a message to the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson (6). He received his response three days later: his orders hadn’t changed a bit. Everyone hoped Villa could be tracked down without antagonising Carranza, but Pershing was prepared to risk escalating the tension to complete his mission. National Guardsmen moved down to the border, and some units from New Mexico crossed to join Pershing in Chihuahua. Meanwhile, in Washington, Mexican ambassador Ignatio Bollinas paid a cool visit to Hughes. President Carranza had ordered him home and expelled the American legation in Mexico City. Mexico’s small army was mobilising, and if Pershing’s expedition “harmed so much as a lizard, stole so much as a bucket of water”, Bollinas said he could give no guarantees as to what would happen next.

On 9 August 1917, Pershing received a tip-off that Pancho Villa was occupying the town of Los Lamentos to prepare for a raid into Texas. The American commander directed his men towards the town and was met with fire. In the chaos of battle, it took some time for the situation to become clear, but an envoy from Carranza’s army approached the American column shortly after ten AM. Villa was in fact in Los Lamentos, and central government troops were trying to capture him. If the Americans intervened, Mexican troops were under orders to ignore them. There was a risk that Mexican bullets would kill Yankee boys… but that had already happened once during this expedition. Worse was the prospect of Villa being captured and carted off to Mexico City. If that happened, Pershing would’ve failed in his mission. Dismissing the envoy, Pershing drew his sword and, like something out of a Western, led his men forward in a cavalry charge. The chaotic Battle of Los Lamentos lasted for less than an hour, and Pancho Villa died in the fighting. However, the Mexican central government troops were driven out of the city after suffering heavy casualties at American hands, and by the end of the day the Stars and Stripes flew over this tiny, impoverished village.

The name of the town- “laments” in English- was awfully fitting. For this was the last straw for Venustiano Carranza. Yankees had encroached upon Mexican territory twice in eighteen months and killed good Mexican soldiers, and now their flag was flying over a town of his. National honour left him with but one choice.

On 11 August 1917, Mexico declared war on the United States of America.

- Including Indochina. In retrospect, I ought to have posted this before chapter 14, as its events occur months before. Oh well, perhaps I’ll edit the threadmarks.

- Since Wilson plays up the “he kept us out of the war” card ITTL, German voters thank him for his neutrality by voting for him in ‘16, since he let the Fatherland win, more or less.

- Moreso than OTL.

- As opposed to “robbing Peter to pay Paul”

- I know next to nothing about economics. If this is really implausible, please tell me and I’ll retcon.

- Hughes decides to keep Gregory on ITTL.

- William Howard Taft’s Secretary of War IOTL; Hughes gives him the job back here.

Last edited:

Share: