No Poles perhaps, but I would still be interested in seeing if you manage to 'relocate' any well-known ETO or MTO Royal Air Force veterans to Malaya ITTL.Ha ha, nice try Nevarinemex, but no Polish 303 Sqn in Malaya, and no Volunteer American pilots there either, creates too many ripples, and very hard to justify on historical grounds, as well as how this TL is shaping.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Malaya What If

- Thread starter Fatboy Coxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 258 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

MWI 41120515 Churchill Wrestles With Matador MWI 41120517 A Heart to Hart MWI 41120519 Operation E MWI 41120519a Japanese OOB for Operation E MWI 41120521 Gort and Phillips Agree On Bullring MWI 41120604 The Sailing Of Force Z MWI 41120514d Royal Navy Eastern Fleet OOB MWI 41120618 Shuffling The PackYou've said what I've TRIED to say and did so in a much clearer fashion than I ever did.You are mispresenting the strategy even of OTL. It was, if Perceval had not dithered, to be in three phases. First launch Operation Matador into Thailand. This would have slowed down the Japanese if successful, the next step was a bit like the Soviets wanted to do (and the Russians had done in 1812), bleed the invaders whilst trading ground to keep forces as intact as possible. All done in the expectation of reinforcements arriving as well as the Monsoon. Last phase would have been to counterattack once sufficient force had arrived, after the Monsoon, driving the invaders back. In no case was it supposed to be, fall back to Singapore and fort up.

Now OTL the Japanese shortcut this by a combination of being able to advance at high-speed, disregarding logistics and a lot of luck in capturing supplies/boats/key locations quickly. Troops that are better trained, know jungle is not impenetrable and have tactics to counter infiltration, will slow the Japanese up. This makes the wheels fall off, if the Japanese don't get to Singapore at OTL speed (as they were all but out of supply by then), they have no option but to pull back to a position they can get decent supply to and pause. This would almost certainly mean the Monsoon stops play and the momentum shifts. (It also means the Burma Campaign almost certainly does not happen as its supplies will have been used to try and force the way to Singapore. So, no Bengal famine and the Japanese having to guard against an attack from the West)

As for the amphibious landings, these need two things the Japanese are likely to be short of, boats (most OTL were captured ones rather than part of the Japanese force so slowly advance means less are likely to be found) and a panicking, lethargic unprepared opponent (a competent commander could easily block the assaults as they would not have much supply or heavy equipment, let alone use proper landing craft). Remember also the longer Singapore holds, the more submarines are going to cripple the Japanese logistics which are marginal to start.

The Japanese cannot just attack Sumatra, they lack everything. OTL the attack was launched after Singapore fell, mainly using forces that had taken Singapore. This because as long as Singapore holds, its near impossible to attack from anywhere but Java. However, the only way to take Java whilst Singapore holds, is by marching across it from the East. Which then brings up the big flaw in the Japanese concentric attacks plan. If they are still fighting heavily in Malaya and so using up all the supplies they can get hold of, they will have very little supply left over for the Central attack which is needed to reach a position to even attack Java from the East.

As you can see, once the Japanese start getting behind schedule or take heavier than expected losses, it quickly becomes a total train wreck. Their plan only works if everything goes right, which it did in OTL. Once things go wrong, it collapses as forces from earlier operations are supposed to be used for later ones. This also is the case for the logistics which assume the fighting has stopped in the earlier operation and so most of its supply operations can be transferred.

If you throw the Japanese plan out whack early on in one place, it begins to unravel EVERYWHERE! It wouldn't have happened overnight, or even in a few weeks, but as losses mount rapidly and badly (especially to shipping assets) on a given campaign, Japanese generals and admirals are going to have to hard choices about where to focus their remaining precious and oft irreplaceable assets.

Last edited:

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

Thank you HMS St.LawrenceYes, the authors go in lenght describing the radar interception tactics developped in the Med. The key factor was (unsurprisingly) altitude. When the enemy was detected, the Fulmar diving speed allowed it to attack the bombers and escape before the escort fighters could intervene. Fulmars were tough enough and their airframes reportedly sustained dive speeds up to 450 mph.

Nice chapter about Hood and Bismarck, here's hoping we'll se more of Prince of Wales soon enough and not in too bad circumstances... I like how the fatal hit to Hood is described in details and your title is on point!

Much of my info on the Hood and Bismarck chapter came from Drachinifel, who's youtube channel I much admire and follow. His video on the loss of Hood is here below.

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

Well so far on the RAF front, I've manged to change a couple of things, both Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, and one of his recently arrived Air Commodores aren't in this theatre historically, see https://www.alternatehistory.com/forum/threads/malaya-what-if.521982/post-23550589No Poles perhaps, but I would still be interested in seeing if you manage to 'relocate' any well-known ETO or MTO Royal Air Force veterans to Malaya ITTL.

Both Stanley Vincent and Henry Hunter were there, but much later, at the beginning of 1942, but Archibald Wann wasn't, and he's quite an interesting chap!

We will see some Battle of Britain veteran pilots in theatre, both historical and new to my timeline, part of my story will feature to some degree, the emergence of ace's, so I'd better brush up on my air combat writing skills!

MWI 41052819 United States Agrees To Negotiate

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

1941, Wednesday 28 May;

They had been talking about opening up negotiations for some time, trying to find some common ground to start discussions from, but their starting points were completely opposing. Nevertheless, for both governments, there had to be talks, if only to formally lay down where they both stood around China and free trade.

Leading the talks were Secretary of State of the USA, Cordell Hull, who at 69, was a highly experienced international statesman, very comfortable working on the world stage. His opposite was Kichisaburo Nomura, 63, who had retired as full Admiral in 1937, then becoming Japan’s Foreign Minister in Nobuyuki Abe’s government 1939-40. On November 27, 1940, he had become ambassador to the United States.

Hull and Nomura had already met, their roles demanded that, and back in April, during the talks to start negotiations, Hull had laid out four basic principles the United States was committed to, on which all relations between nations should properly rest, namely,

One, respect for the territorial integrity and sovereignty of each and all nations.

Two, non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries.

Three, Equality of commercial opportunity.

Four, Non-disturbance of the status quo of the Pacific, except by peaceful means.

Hull also made clear to Nomura, that the United States would not recognise the New Order in East Asia, nor the retention of territory acquired through aggression.

The Japanese had responded on the 12th May, with their draft of proposals which to the layman was flowered with obscure and platitudinous terms, but which could be boiled down to,

One, the USA would agree to recognise the establishment by Japan of the New Order in China, in accordance with Konoye’s three principles as embodied in the Japan-Manchukuo-China Joint Declaration of 30 November 1940, and to advise Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek to negotiate peace with Japan forthwith

Two, to enter into a secret agreement with Japan to withdraw aid to the National Government of China if the Generalissimo did not enter into negotiations for peace.

Three, to recognise the right of Japan to establish the Co-Prosperity Sphere embracing China and the Southern Area upon the understanding that Japan’s expansion in that area was to be of a peaceful nature and to cooperate in producing and procuring from this sphere the natural resources which Japan needs.

Four, to amend its laws on immigration so as to admit Japanese National on the basis of equality and non-discrimination

Five, to restore normal economic relations between the two countries.

Six, to take note of Japan’s obligation under Article 3 of the Tripartite Pact to attack the United States if in the opinion of the Japanese Government the assistance rendered to the Allied Powers resisting Germany and Italy mounted to an attack upon the Axis

Seven, to refrain from rendering assistance to the Allied Powers

The Japanese in return would agree to

One, resume normal trade relations with the United States

Two, assure the United States a supply of the commodities available in the Co-Prosperity Sphere

Three, join the United States in a guarantee of the independence of the Philippines on the condition that the Philippines would maintain a status of permanent neutrality.

The United States Government accepted the Japanese draft proposals as a starting point for negotiations to begin, and talks had started this morning. For the Americans, during the course of conversations, it became clear there were two major obstacles to any successful prosecution of the negotiations.

One, the obscurity in which Japan’s commitments under the Tripartite Pact were at present, Hull had asked Nomura to qualify its attitude towards the possible event of the United States being drawn into the European War as a measure of self-defence, and

Two, the provisions for settlement of the China question, Japan’s insistence on retaining troops in China after the conclusion of any peace treaty.

Later that evening after the first day’s talks were done, Hull had the opportunity to reflect on what had been said, and concluded that between the intercepts of coded Japanese diplomatic talk and what was said today, the current economical embargos were not having the desired effect on Japan’s willingness to compromise. Clearly these were going to be exceedingly difficult talks.

They had been talking about opening up negotiations for some time, trying to find some common ground to start discussions from, but their starting points were completely opposing. Nevertheless, for both governments, there had to be talks, if only to formally lay down where they both stood around China and free trade.

Leading the talks were Secretary of State of the USA, Cordell Hull, who at 69, was a highly experienced international statesman, very comfortable working on the world stage. His opposite was Kichisaburo Nomura, 63, who had retired as full Admiral in 1937, then becoming Japan’s Foreign Minister in Nobuyuki Abe’s government 1939-40. On November 27, 1940, he had become ambassador to the United States.

Hull and Nomura had already met, their roles demanded that, and back in April, during the talks to start negotiations, Hull had laid out four basic principles the United States was committed to, on which all relations between nations should properly rest, namely,

One, respect for the territorial integrity and sovereignty of each and all nations.

Two, non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries.

Three, Equality of commercial opportunity.

Four, Non-disturbance of the status quo of the Pacific, except by peaceful means.

Hull also made clear to Nomura, that the United States would not recognise the New Order in East Asia, nor the retention of territory acquired through aggression.

The Japanese had responded on the 12th May, with their draft of proposals which to the layman was flowered with obscure and platitudinous terms, but which could be boiled down to,

One, the USA would agree to recognise the establishment by Japan of the New Order in China, in accordance with Konoye’s three principles as embodied in the Japan-Manchukuo-China Joint Declaration of 30 November 1940, and to advise Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek to negotiate peace with Japan forthwith

Two, to enter into a secret agreement with Japan to withdraw aid to the National Government of China if the Generalissimo did not enter into negotiations for peace.

Three, to recognise the right of Japan to establish the Co-Prosperity Sphere embracing China and the Southern Area upon the understanding that Japan’s expansion in that area was to be of a peaceful nature and to cooperate in producing and procuring from this sphere the natural resources which Japan needs.

Four, to amend its laws on immigration so as to admit Japanese National on the basis of equality and non-discrimination

Five, to restore normal economic relations between the two countries.

Six, to take note of Japan’s obligation under Article 3 of the Tripartite Pact to attack the United States if in the opinion of the Japanese Government the assistance rendered to the Allied Powers resisting Germany and Italy mounted to an attack upon the Axis

Seven, to refrain from rendering assistance to the Allied Powers

The Japanese in return would agree to

One, resume normal trade relations with the United States

Two, assure the United States a supply of the commodities available in the Co-Prosperity Sphere

Three, join the United States in a guarantee of the independence of the Philippines on the condition that the Philippines would maintain a status of permanent neutrality.

The United States Government accepted the Japanese draft proposals as a starting point for negotiations to begin, and talks had started this morning. For the Americans, during the course of conversations, it became clear there were two major obstacles to any successful prosecution of the negotiations.

One, the obscurity in which Japan’s commitments under the Tripartite Pact were at present, Hull had asked Nomura to qualify its attitude towards the possible event of the United States being drawn into the European War as a measure of self-defence, and

Two, the provisions for settlement of the China question, Japan’s insistence on retaining troops in China after the conclusion of any peace treaty.

Later that evening after the first day’s talks were done, Hull had the opportunity to reflect on what had been said, and concluded that between the intercepts of coded Japanese diplomatic talk and what was said today, the current economical embargos were not having the desired effect on Japan’s willingness to compromise. Clearly these were going to be exceedingly difficult talks.

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

The above chapter should read as was historically, there being no change here.

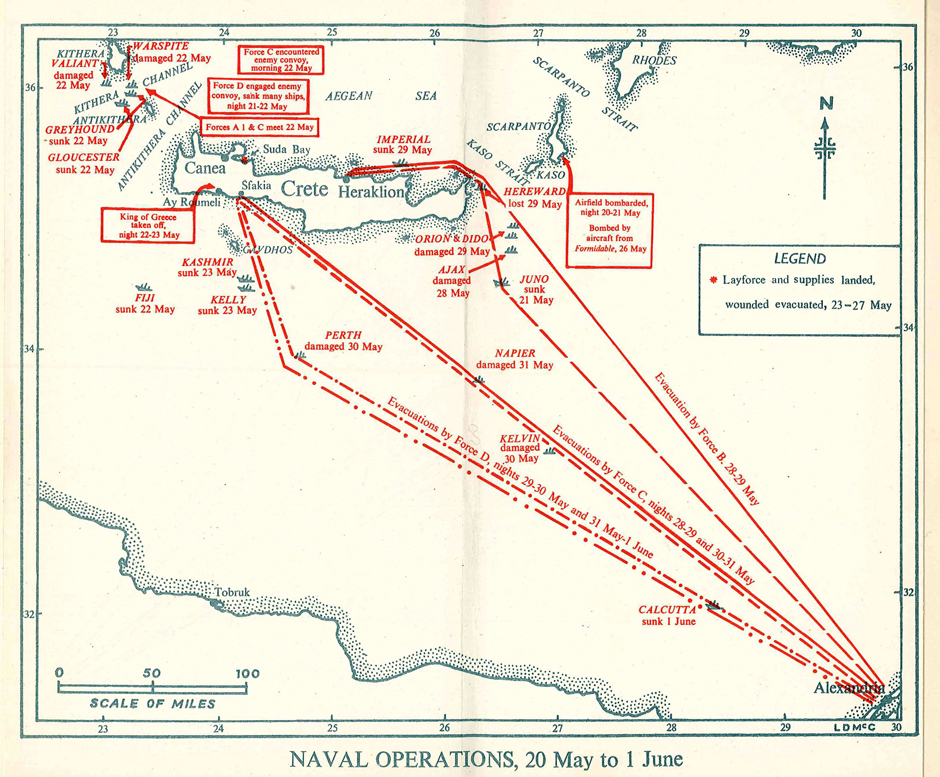

MWI 41052910 Crete

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

1941, Thursday 29 May;

The runner came, breathing hard, crouched over, running a zigzag, conscious of snipers. Vic watched him stop by the captain, a quick conversation, the officer slapping him on the back, and the runner was off again, returning back down the road to the harbour of Heraklion. The word came round, time to go, no noise or fuss, just quietly, but fast, the Navy wasn’t going to wait for ever. Sgt Victor Babbs, 2/4 Australian Bn, slung the strap over his neck and shoulder, and picked the Bren up, his two companions following. 50 yards, then stop, down on the belly, and set the Bren up, waiting for the other group to leapfrog pass, then again, up and jog, the machine gun becoming progressively heavier with the physical effort, Vic sweating now despite the cool night.

Up to the harbour gates, down on his belly again, Bren set, ready to fire, the captain coming, urging a couple of panting soldiers on, who ran by him, the captain stopping, down on one knee. “Hang on Vic, there’s another party to come”. They waited, the night silent, the Germans hadn’t rumbled them yet. The seconds dripped by, each one an hour, come on, come on, whats holding you up. There they are, several figures, a couple really staggering, looking all in. Wounded, he could see dirty, bloodied bandaging, they’d never make it. He whispered to his second, ‘take the Bren’, unslinging it, and he was up, making great strides across the square to the staggering men.

Shouting voices could be heard, German, they’d discovered the empty positions, they’d be here soon, it gave more urgency to his run. He was up to them now, D company men, he recognised a couple of them. “Lieutenant Woods copped a bullet as we were pulling out” a soldier said, the officer’s right arm pulled over his shoulder. “We couldn’t leave him” “Well let me take him now, or we’ll all miss the boat” Vic said, and hoisted the officer up onto his shoulder in a fireman’s carry. Vic turned and started a slow run, part staggering, but gaining speed, across the square, through the harbour gates and down to the quay, the others all running with him.

The destroyer, HMS Imperial lay there, her engines running, just two ropes holding her to the quayside, a single wood gangway left. He staggered up to it, a couple of matelots taking the wounded man from him, a young naval officer standing with them motioned everyone aboard, then gave a wave as he hurried across. The ropes dropped free, the wooden gangway fell into the harbour, as the ship swung away, her screws churning the sediment off the bottom into a creamy dirty froth and she began to make way, for the harbour entrance. Vic staggered against the ship’s superstructure, and fell to all fours, all in, his lungs gasping in the oxygen. “Bloody marvellous Vic, well done Blue, every man away thanks to you” Vic looked up at his Captain, but could only smile, not yet capable of speaking.

The destroyer cleared the harbour, her signal light blinking out the news to the awaiting ships, all turning east, to run along the coast, round the end of Crete, then south to Egypt and safety. For twenty minutes it was idyllic, the soldiers lay there, the throbbing of the engines giving a soothing massage to tired men, relaxing them. Then suddenly chaos descended, Naval officers shouting, signal lights frantically blinking, and first one, then a second big grey ship loomed up at them, both just missing due to some frantic manoeuvring. The steering gear on HMS Imperial had failed, she’d had a near miss on the journey here, but had thought she’d avoided damage, but now, clearly something had given, broken.

No time to organise a tow, or fix a repair, the night was their biggest ally, they had to make all speed and put distance between them and Crete. With a heavy heart, the Admiral made the difficult decision, HMS Hotspur came alongside, and everybody was being hurried across gangplanks, the two ships bobbing up and down, sailors’ hands reaching out, grabbing unsteady soldiers, helping them, calling when to stop, when to go, as 900 troops now crammed on the destroyer, along with Imperial’s crew. An hour lost, over 30 miles in distance, it couldn’t be helped. And then they were away again, racing along at 29 knots towards the Kasos Straits, while Imperial settled down into the water, scuttled by her own crew.

With just a sliver of moon, hidden by cloud, the night had been pitch-black, prefect for what they were doing, but it had all taken too long. Now they could make out the shapes of comrades and parts of the ship, as the predawn light appeared. On the bridge of HMS Orion, Rear Admiral Bernard Rawlings was called as he’d requested, and consulted his charts, they were just entering the Kasos Straits. Force B, as his command was called, was crowded with the 4,000 men, mostly of the British 14th Brigade, not ideal if you’re about to face heavy air attacks for the best part of the day.

The ships went to action stations, to greet the dawn, the sailors struggling, having to pick their way among the soldiers carried on the ships. And with the dawn came the Luftwaffe, who at intervals, would stay with them until 3pm, when the ships were within 100 miles of Alexandria. For the troops, this was an experience they’d come to get used to, except there had always been some shelter, however crude to hid in and hope the bombs didn’t have your number. Now, wedged in passageways, small compartments, they would be prey to the fears of the unknown, left to hear the battle, and imagine what was happening, or worse, sat outside, huddled tight together, exposed to sun, sea spray and the shrapnel and splinters of exploding bombs, and AA shells.

The first attack began at 6am, but sailing at high speed, weaving about, the ships were hard to hit. The Germans weren’t nothing if not persistent, and their efforts were rewarded 25 minutes later, when the destroyer HMS Hereward was hit by a bomb just in front of her forward funnel, which forced a reduction in speed, falling away from her position in the screen. Rawlings had to make the unpleasant decision of abandoning Hereward to her fate, and push on, the damaged destroyer turning towards Crete, about five miles distant, in the vain hope of beaching and saving her crew and army evacuees.

The attacks kept coming, on board HMS Decoy was Corporal Eddie James, of the 7th Medium Regt RA, which had been sent to Crete after its evacuation from Greece minus their guns, and employed as infantry. Eddie had been horrified to be given a Lee-Enfield, he hadn’t used one since basic training, and even more so when he’d had to use it on the German paratroopers, feeling quite sick killing men who were helpless, slung under their canopies. Those thoughts were quickly forgotten once the elite troops were on the ground, armed from their weapon containers, and shooting back.

The relief he felt when he heard they were being evacuated only lasted the 20 minutes it took to leave the foxholes they were in and make their way to the harbour. While edging their way down a rocky gorge, he’d slipped and fallen in the dark, breaking an arm and cracking several ribs. Morphine was in short supply, and held back for the seriously wounded, he had been told by the MO to ’be a good chap and don’t make too much fuss, its only broken’ while his arm was put in a sling, and his chest bandaged up. Now, with the pain of just physically breathing, along with some sea sickness due to the ships high speed manoeuvres, wedged in a corner, below decks, he was somewhat distracted from the air attacks.

That was until the near miss, a Stuka’s aim being off thanks to the skill of the ship’s captain, ordering yet another turn, but nevertheless it was close, too close, the pressure wave and subsequent vibration as the ship responded, damaging her machinery, forcing a reduction in speed to 25 knots, which the rest of the squadron followed, keen to remain together in the interested of collective defence. Eddie was thrown sideways, into the back of another soldier, with a heavily bandaged head, apologising, despite his own sudden pain, when he saw the ash grey face screw up in contorted pain. ‘Sorry mate’ was about all that could be said, a replied thumbs up was given.

The air attack over, the ships tidied their station keeping, while on each ship further ammunition was being brought up, refilling ready use lockers, the ships galley doing their best to give everyone a cup of hot tea and a piece of cake, sandwich, anything, to put something in their bellies, today was going to be a long day. Rawlings, out on the bridge wing of HMS Orion, looked around, just themselves now, the land mass of Crete had fallen over the horizon. HMS Dido was faithfully following, the destroyers Hotspur, Jackal, Decoy and Kimberley alongside them

Here they come again, not even 8 o’clock, and they were facing their third air attack, Stuka’s, alone, quite safe, there being no RAF air cover. Lt Stanley Dunstan, 1st Bn, Leicestershire Regt, was on HMS Orion with his platoon, down in one of the mess decks. Exhaustion from over a week of combat, the men had tried to rest, relieved to be away from it all. On the first day of the German attack, they’d sat in their trenches and mostly watched the action unfound elsewhere, as the air assault began. One Ju52 had flown over their positions, and all the paratroopers that jumped out had either been killed or wounded before they landed. However, the next day they had begun patrolling, searching out the small pockets of Germans before they had a chance to link up and formed into effective fighting units. The work was hard, the ground unrelenting, with lots of potential places to hide behind. He’d lost a couple of men while winkling out German survivors. Gradually, over the next few days, things had quietened down a bit, both sides content to hold what they had, while the real battle for the island was fought elsewhere.

The withdrawal had gone well for them, the company was led down to the harbour, and put on a destroyer, which took them out beyond the harbour, to transfer over to the bigger ship. Tea and a sandwich, along with being away from the sun-drenched rocks and dust was just heaven. And for a few hours they’d slept a bit, despite being crammed in like sardines. Then dawn, and it had all begun, firstly with the crew moving to their action stations, then the noise of the 4-inch AA guns firing, the sounds reverberating around the mess deck, the ship noticeably moving about more, as the she fought off an air attack. Ten minutes, maybe fifteen and then it was over, only, half an hour later, they were at it again, Stan and his men huddled below decks, unaware of how things were progressing, crammed in with hundreds of other soldiers, eyes looking upwards, wondering.

Mid-morning, another attack, the Stuka pilot, an experienced two-year vet, took careful aim, aware the ship would twist and turn as he dived, guessed the direction and dropped his egg, before releasing his air brakes, pulling back the stick, and opening up the throttle, desperate to avoid the lines of fire from the 0.5-inch quad mounts. The ship had already been hit a couple of times earlier, her captain dead from bomb splinters, her ‘A’ turret knocked out. HMS Orion had nearly 1100 troops on board, mostly down below decks. This time, the bomb went through the deck and penetrated the mess deck before exploding. The result was carnage, there was no escaping it, and in a wink of an eye a couple of hundred men died, many bodies torn into pieces, as parts of the structure of the ship splintered and cut their way through ranks of men. Further away from the blast they didn’t die, at least not at first, but for many, the sheer number of wounded meant many bled to death, unattended.

Stan was lucky, the captain he was talking to at the time shielded him, stopping several pieces of flying shrapnel, which had already sliced through numerous other bodies, excepting a couple of small pieces which took away part of Stans left ear, and torn into his shoulder. The captains head, propelled forward, broke Stans nose and gave him a couple of black eyes. As the noise of the explosion abated, so the cries, screams and high-pitched sounds of unimaginable pain began, as hundreds of men began their individual struggles to live. Stan would never talk about what happened over the next 12 hours, the few times he did, he cried uncontrollably, but the memories of that horror lived with him for the rest of his life.

Force B crept into Alexandria harbour at 8pm, battered, having lost two destroyers, both cruisers needing dockyard repairs, while over 800 men out of the 4,000 evacuated, of the British 14th Brigade, were lost, many on the Hereward or the Orion. The loss of Crete was a huge blow to Britain, greatly weakening their position in the Middle East, both strategically, and in their military capability due to the heavy losses incurred among all three services. The Royal Navy lost 4 cruisers and 6 destroyers, while an aircraft carrier, 2 battleships, 4 cruisers and a couple of destroyers at least, would be out of action for months. The RAF was badly depleted in Greece, while the Army lost over 15,000 men in Crete, but more importantly, the New Zealand and 6th Australian Divisions, along with the British 1st Armoured Brigade, had been mauled in Greece, The Kiwi’s and Aussies were furthered battered in Crete, and all three formations required rebuilding, having lost most of their heavy equipment.

Just how closely they lost the battle of Crete, wasn’t really appreciated by the Allies until after the war, and the huge losses taken by the German airborne forces was overlooked, other nations preferring to take notice of their successes, creating the need to raised parachutes formations themselves. Strategically, Luftwaffe aircraft flying from airfields in Crete were able to interdict supplies from Alexandria to Malta, and posed a considerable threat to the whole of the Eastern Med, being in range of Cyprus, Palestine and Egypt, forcing the British into deploying additional defensive forces. It also made the threat of German intervention in Iraq and Persia more likely, probably using Vichy held Syria. For the British in the North Africa, it was almost like a rewind back to December 1940, only Rommel was now on the scene, and things were going to get a lot more difficult.

The runner came, breathing hard, crouched over, running a zigzag, conscious of snipers. Vic watched him stop by the captain, a quick conversation, the officer slapping him on the back, and the runner was off again, returning back down the road to the harbour of Heraklion. The word came round, time to go, no noise or fuss, just quietly, but fast, the Navy wasn’t going to wait for ever. Sgt Victor Babbs, 2/4 Australian Bn, slung the strap over his neck and shoulder, and picked the Bren up, his two companions following. 50 yards, then stop, down on the belly, and set the Bren up, waiting for the other group to leapfrog pass, then again, up and jog, the machine gun becoming progressively heavier with the physical effort, Vic sweating now despite the cool night.

Up to the harbour gates, down on his belly again, Bren set, ready to fire, the captain coming, urging a couple of panting soldiers on, who ran by him, the captain stopping, down on one knee. “Hang on Vic, there’s another party to come”. They waited, the night silent, the Germans hadn’t rumbled them yet. The seconds dripped by, each one an hour, come on, come on, whats holding you up. There they are, several figures, a couple really staggering, looking all in. Wounded, he could see dirty, bloodied bandaging, they’d never make it. He whispered to his second, ‘take the Bren’, unslinging it, and he was up, making great strides across the square to the staggering men.

Shouting voices could be heard, German, they’d discovered the empty positions, they’d be here soon, it gave more urgency to his run. He was up to them now, D company men, he recognised a couple of them. “Lieutenant Woods copped a bullet as we were pulling out” a soldier said, the officer’s right arm pulled over his shoulder. “We couldn’t leave him” “Well let me take him now, or we’ll all miss the boat” Vic said, and hoisted the officer up onto his shoulder in a fireman’s carry. Vic turned and started a slow run, part staggering, but gaining speed, across the square, through the harbour gates and down to the quay, the others all running with him.

The destroyer, HMS Imperial lay there, her engines running, just two ropes holding her to the quayside, a single wood gangway left. He staggered up to it, a couple of matelots taking the wounded man from him, a young naval officer standing with them motioned everyone aboard, then gave a wave as he hurried across. The ropes dropped free, the wooden gangway fell into the harbour, as the ship swung away, her screws churning the sediment off the bottom into a creamy dirty froth and she began to make way, for the harbour entrance. Vic staggered against the ship’s superstructure, and fell to all fours, all in, his lungs gasping in the oxygen. “Bloody marvellous Vic, well done Blue, every man away thanks to you” Vic looked up at his Captain, but could only smile, not yet capable of speaking.

The destroyer cleared the harbour, her signal light blinking out the news to the awaiting ships, all turning east, to run along the coast, round the end of Crete, then south to Egypt and safety. For twenty minutes it was idyllic, the soldiers lay there, the throbbing of the engines giving a soothing massage to tired men, relaxing them. Then suddenly chaos descended, Naval officers shouting, signal lights frantically blinking, and first one, then a second big grey ship loomed up at them, both just missing due to some frantic manoeuvring. The steering gear on HMS Imperial had failed, she’d had a near miss on the journey here, but had thought she’d avoided damage, but now, clearly something had given, broken.

No time to organise a tow, or fix a repair, the night was their biggest ally, they had to make all speed and put distance between them and Crete. With a heavy heart, the Admiral made the difficult decision, HMS Hotspur came alongside, and everybody was being hurried across gangplanks, the two ships bobbing up and down, sailors’ hands reaching out, grabbing unsteady soldiers, helping them, calling when to stop, when to go, as 900 troops now crammed on the destroyer, along with Imperial’s crew. An hour lost, over 30 miles in distance, it couldn’t be helped. And then they were away again, racing along at 29 knots towards the Kasos Straits, while Imperial settled down into the water, scuttled by her own crew.

With just a sliver of moon, hidden by cloud, the night had been pitch-black, prefect for what they were doing, but it had all taken too long. Now they could make out the shapes of comrades and parts of the ship, as the predawn light appeared. On the bridge of HMS Orion, Rear Admiral Bernard Rawlings was called as he’d requested, and consulted his charts, they were just entering the Kasos Straits. Force B, as his command was called, was crowded with the 4,000 men, mostly of the British 14th Brigade, not ideal if you’re about to face heavy air attacks for the best part of the day.

The ships went to action stations, to greet the dawn, the sailors struggling, having to pick their way among the soldiers carried on the ships. And with the dawn came the Luftwaffe, who at intervals, would stay with them until 3pm, when the ships were within 100 miles of Alexandria. For the troops, this was an experience they’d come to get used to, except there had always been some shelter, however crude to hid in and hope the bombs didn’t have your number. Now, wedged in passageways, small compartments, they would be prey to the fears of the unknown, left to hear the battle, and imagine what was happening, or worse, sat outside, huddled tight together, exposed to sun, sea spray and the shrapnel and splinters of exploding bombs, and AA shells.

The first attack began at 6am, but sailing at high speed, weaving about, the ships were hard to hit. The Germans weren’t nothing if not persistent, and their efforts were rewarded 25 minutes later, when the destroyer HMS Hereward was hit by a bomb just in front of her forward funnel, which forced a reduction in speed, falling away from her position in the screen. Rawlings had to make the unpleasant decision of abandoning Hereward to her fate, and push on, the damaged destroyer turning towards Crete, about five miles distant, in the vain hope of beaching and saving her crew and army evacuees.

The attacks kept coming, on board HMS Decoy was Corporal Eddie James, of the 7th Medium Regt RA, which had been sent to Crete after its evacuation from Greece minus their guns, and employed as infantry. Eddie had been horrified to be given a Lee-Enfield, he hadn’t used one since basic training, and even more so when he’d had to use it on the German paratroopers, feeling quite sick killing men who were helpless, slung under their canopies. Those thoughts were quickly forgotten once the elite troops were on the ground, armed from their weapon containers, and shooting back.

The relief he felt when he heard they were being evacuated only lasted the 20 minutes it took to leave the foxholes they were in and make their way to the harbour. While edging their way down a rocky gorge, he’d slipped and fallen in the dark, breaking an arm and cracking several ribs. Morphine was in short supply, and held back for the seriously wounded, he had been told by the MO to ’be a good chap and don’t make too much fuss, its only broken’ while his arm was put in a sling, and his chest bandaged up. Now, with the pain of just physically breathing, along with some sea sickness due to the ships high speed manoeuvres, wedged in a corner, below decks, he was somewhat distracted from the air attacks.

That was until the near miss, a Stuka’s aim being off thanks to the skill of the ship’s captain, ordering yet another turn, but nevertheless it was close, too close, the pressure wave and subsequent vibration as the ship responded, damaging her machinery, forcing a reduction in speed to 25 knots, which the rest of the squadron followed, keen to remain together in the interested of collective defence. Eddie was thrown sideways, into the back of another soldier, with a heavily bandaged head, apologising, despite his own sudden pain, when he saw the ash grey face screw up in contorted pain. ‘Sorry mate’ was about all that could be said, a replied thumbs up was given.

The air attack over, the ships tidied their station keeping, while on each ship further ammunition was being brought up, refilling ready use lockers, the ships galley doing their best to give everyone a cup of hot tea and a piece of cake, sandwich, anything, to put something in their bellies, today was going to be a long day. Rawlings, out on the bridge wing of HMS Orion, looked around, just themselves now, the land mass of Crete had fallen over the horizon. HMS Dido was faithfully following, the destroyers Hotspur, Jackal, Decoy and Kimberley alongside them

Here they come again, not even 8 o’clock, and they were facing their third air attack, Stuka’s, alone, quite safe, there being no RAF air cover. Lt Stanley Dunstan, 1st Bn, Leicestershire Regt, was on HMS Orion with his platoon, down in one of the mess decks. Exhaustion from over a week of combat, the men had tried to rest, relieved to be away from it all. On the first day of the German attack, they’d sat in their trenches and mostly watched the action unfound elsewhere, as the air assault began. One Ju52 had flown over their positions, and all the paratroopers that jumped out had either been killed or wounded before they landed. However, the next day they had begun patrolling, searching out the small pockets of Germans before they had a chance to link up and formed into effective fighting units. The work was hard, the ground unrelenting, with lots of potential places to hide behind. He’d lost a couple of men while winkling out German survivors. Gradually, over the next few days, things had quietened down a bit, both sides content to hold what they had, while the real battle for the island was fought elsewhere.

The withdrawal had gone well for them, the company was led down to the harbour, and put on a destroyer, which took them out beyond the harbour, to transfer over to the bigger ship. Tea and a sandwich, along with being away from the sun-drenched rocks and dust was just heaven. And for a few hours they’d slept a bit, despite being crammed in like sardines. Then dawn, and it had all begun, firstly with the crew moving to their action stations, then the noise of the 4-inch AA guns firing, the sounds reverberating around the mess deck, the ship noticeably moving about more, as the she fought off an air attack. Ten minutes, maybe fifteen and then it was over, only, half an hour later, they were at it again, Stan and his men huddled below decks, unaware of how things were progressing, crammed in with hundreds of other soldiers, eyes looking upwards, wondering.

Mid-morning, another attack, the Stuka pilot, an experienced two-year vet, took careful aim, aware the ship would twist and turn as he dived, guessed the direction and dropped his egg, before releasing his air brakes, pulling back the stick, and opening up the throttle, desperate to avoid the lines of fire from the 0.5-inch quad mounts. The ship had already been hit a couple of times earlier, her captain dead from bomb splinters, her ‘A’ turret knocked out. HMS Orion had nearly 1100 troops on board, mostly down below decks. This time, the bomb went through the deck and penetrated the mess deck before exploding. The result was carnage, there was no escaping it, and in a wink of an eye a couple of hundred men died, many bodies torn into pieces, as parts of the structure of the ship splintered and cut their way through ranks of men. Further away from the blast they didn’t die, at least not at first, but for many, the sheer number of wounded meant many bled to death, unattended.

Stan was lucky, the captain he was talking to at the time shielded him, stopping several pieces of flying shrapnel, which had already sliced through numerous other bodies, excepting a couple of small pieces which took away part of Stans left ear, and torn into his shoulder. The captains head, propelled forward, broke Stans nose and gave him a couple of black eyes. As the noise of the explosion abated, so the cries, screams and high-pitched sounds of unimaginable pain began, as hundreds of men began their individual struggles to live. Stan would never talk about what happened over the next 12 hours, the few times he did, he cried uncontrollably, but the memories of that horror lived with him for the rest of his life.

Force B crept into Alexandria harbour at 8pm, battered, having lost two destroyers, both cruisers needing dockyard repairs, while over 800 men out of the 4,000 evacuated, of the British 14th Brigade, were lost, many on the Hereward or the Orion. The loss of Crete was a huge blow to Britain, greatly weakening their position in the Middle East, both strategically, and in their military capability due to the heavy losses incurred among all three services. The Royal Navy lost 4 cruisers and 6 destroyers, while an aircraft carrier, 2 battleships, 4 cruisers and a couple of destroyers at least, would be out of action for months. The RAF was badly depleted in Greece, while the Army lost over 15,000 men in Crete, but more importantly, the New Zealand and 6th Australian Divisions, along with the British 1st Armoured Brigade, had been mauled in Greece, The Kiwi’s and Aussies were furthered battered in Crete, and all three formations required rebuilding, having lost most of their heavy equipment.

Just how closely they lost the battle of Crete, wasn’t really appreciated by the Allies until after the war, and the huge losses taken by the German airborne forces was overlooked, other nations preferring to take notice of their successes, creating the need to raised parachutes formations themselves. Strategically, Luftwaffe aircraft flying from airfields in Crete were able to interdict supplies from Alexandria to Malta, and posed a considerable threat to the whole of the Eastern Med, being in range of Cyprus, Palestine and Egypt, forcing the British into deploying additional defensive forces. It also made the threat of German intervention in Iraq and Persia more likely, probably using Vichy held Syria. For the British in the North Africa, it was almost like a rewind back to December 1940, only Rommel was now on the scene, and things were going to get a lot more difficult.

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

Apart from the three fictitious characters I have introduced, this is all historical

Errolwi

Monthly Donor

Excellent writing!

You can see why that was the last evacuation from the north coast.

Note below the run on 31 May/1st June, done at the strong urging of the NZ Prime Minister (in Cairo). They got away with it, the Luftwaffe withdrawn for Russia.

nzhistory.govt.nz

nzhistory.govt.nz

You can see why that was the last evacuation from the north coast.

Note below the run on 31 May/1st June, done at the strong urging of the NZ Prime Minister (in Cairo). They got away with it, the Luftwaffe withdrawn for Russia.

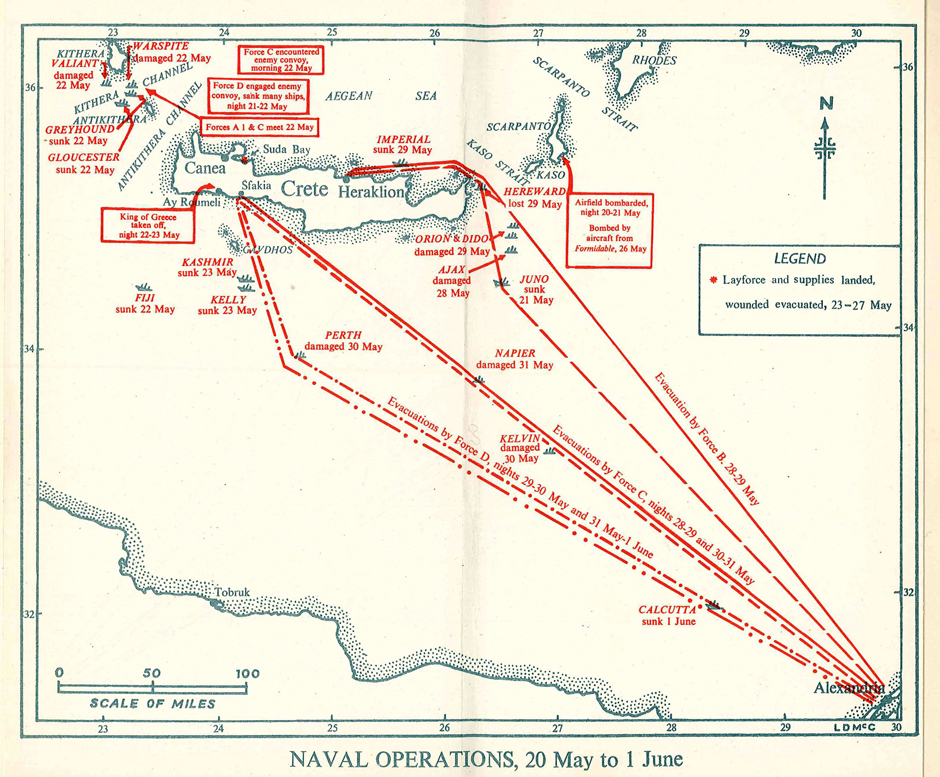

British naval operations around Crete, 20 May-1 June 1941

Map showing British naval operations around Crete, 20 May - 1 June 1941

Well written, but a distraction from your main narrative. I'm not sure I see a point. There are vast areas of OTL WW II narrative one could include but which wouldn't advance the story being told.Apart from the three fictitious characters I have introduced, this is all historical

Driftless

Donor

Well written, but a distraction from your main narrative. I'm not sure I see a point. There are vast areas of OTL WW II narrative one could include but which wouldn't advance the story being told.

I can see your point about diverting attention - I won't call it a distraction. But I also appreciate that these diversions clearly point out at this stage of the war, Malaya is the deepest, sleepiest backwater of the Empire in a desperate war. The Allied brass* knows Malaya and SE Asia could heat up real fast, but even they can't indulge their best intentions too far.

* I first typed Empire Brass, but that might have created a wrong note....

Last edited:

Errolwi

Monthly Donor

And the interplay of Empire is shown by:I can see your point about diverting attention - I won't call it a distraction. But I also appreciate that these diversions clearly point out at this stage of the war, Malaya is the deepest, sleepiest backwater of the Empire in a desperate war. The Allied brass* knows Malaya and SE Asia could heat up real fast, but even they can't indulge their best intentions too far.

* I first typed Empire Brass, but that might have created a wrong note....

The RAF was badly depleted in Greece, while the Army lost over 15,000 men in Crete, but more importantly, the New Zealand and 6th Australian Divisions, along with the British 1st Armoured Brigade, had been mauled in Greece, The Kiwi’s and Aussies were furthered battered in Crete, and all three formations required rebuilding, having lost most of their heavy equipment.

I can see your point about diverting attention - I won't call it a distraction. But I also appreciate that these diversions clearly point out at this stage of the war, Malaya is the deepest, sleepiest backwater of the Empire in a desperate war. The Allied brass* knows Malaya and SE Asia could heat up real fast, but even they can't indulge their best intentions too far.

* I first typed Empire Brass, but that might have created a wrong note....

Agree with this.....

Malaya was a backwater in comparison to the main theatre in Europe and so at least keeping track of events happening there are critical to understand the the resources available in the Malayan theatre where the main butterflied storyline is taking place.

Menzies was already Prime Minister of Australia. He believed on his visit to the UK just before he lost the confidence of the Australian Parliament, that he had chance of becoming the PM of the UK if he stood for election, poor, deluded, fool.As to a point, I am hoping that the Dominion's will "grow a pair" and ask why their lives and resources are being squandered, when they should be closer to home.. There seems to be concern shown by the NZ PM. Menzies might pipe up if he is in consideration for PM and will receive an obligatory drum and fife band. Or at least some pipers.

About right. Metaxas insisted that the Greeks would only accept ground forces if they were at least 9 Divisions. Crafty old bloke knew there were not even 9 divisions in the entire middle East. Although there had been RAF units on the ground in Greece since Nov(?) 1940, they did not attack German targets, only Italian ones.As I understand it the Greek PM GEN Metaxas declined when the British offered troops for two reasons. The first reason being too few troops. The second, it was likely to provoke the Germans to action. After GEN Metaxas died, the King of Greece installed a new PM who was strong armed into approving the plan.

Australian PM Menzies was present at the British War Cabinet meeting which approved the Greece operation. However, he did not inform his ME Commander GEN Blamey of his intention to approve the operation. GEN Blamey was leery about a positive outcome, however, he was left out of the loop. Hence, he believed that PM Menzies had approved the action. PM Menzies thought that GEN Wavell had informed GEN Blamey, who only informed the AUS commander at a later time.

Does this sound right?

Interesting sidebar is that when Eden went to Greece in Feb 41, Churchill told him to be careful as if there was the possibility of another Dunkirk, Eden was fully justified and not agreeing to send troops.

It was too late though. Hitler had already ordered planning for the invasion of Greece in Nov. So all those stories about how at least Greece meant the diversion of German forces from Barbarossa are just that, stories.

As for Menzies and Blamey, ISTR that Menzies thought or was told at the War Cabinet meeting in London that Blamey had agreed on the military need to go into Greece, while Blamey had done no such thing. However, he was told that Menzies had agreed so he started the planning. By the time the confusion was cleared up, it was too late to pull the ANZAC troops out of the convoys to Greece.

Well that's certainly an opinionChurchill did things for the UK's benefit. He basically didn't give a damn about Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders or South Africans. He lied to Menzies, he later lied to Curtin. It was all to benefit the UK.

Not sure if its backed up by any facts though?

What was this lie/lies then?

Churchill concealed the route of the AIF divisions from the Middle-East when they were recalled home. Churchill believed they were more useful in Rangoon rather than as was initially supposed the NEI and then later in Australia. The Australian Government believed that London would abide by the agreement which governed their deployment to the Middle-East. Churchill did not. He changed the course not once but twice without telling Canberra and Canberra reacted most negatively to the news when they learned it. The ships had not been loaded tactically because of the hurriedness of their redeployment and when Churchill learnt that he relented and ordered them back to Trincomalee to refuel. This only occurred after some terse exchange of telegrams between London and Canberra. If they had reached Rangoon, there is no doubt they would have gone straight into the Japanese bag.Well that's certainly an opinion

Not sure if its backed up by any facts though?

What was this lie/lies then?

That was his worse effort, but not his only one. Churchill was not to be trusted.

Errolwi

Monthly Donor

It's unfair to demonize Churchill alone on this, it was the approach of most of the UK politico-military establishment (but the boss sets the tone of course). A similar bait and switch was done with the NZ Government and Freyberg to get the NZ Division rushed to Greece. As well as direct lies during the evacuation of Crete. Note that the Royal Navy got a thank you note post Crete from the NZ Govt.

...

General Evetts rang the Commander-in-Chief, General Wavell, and was informed that a modified cablegram had been sent to General Freyberg and that, as there was delay in reaching me [NZ PM Peter Fraser], officers of the General Staff had attached my name to it. I immediately stated that this should not have been done. Next morning General Freyberg was very much relieved to know that I had not authorised my signature to that particular cablegram.

...

Threadmarks

View all 258 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

MWI 41120515 Churchill Wrestles With Matador MWI 41120517 A Heart to Hart MWI 41120519 Operation E MWI 41120519a Japanese OOB for Operation E MWI 41120521 Gort and Phillips Agree On Bullring MWI 41120604 The Sailing Of Force Z MWI 41120514d Royal Navy Eastern Fleet OOB MWI 41120618 Shuffling The Pack

Share: