Not dead, just on hiatus. Will resume if there is interest.

Mucho interest.

Not dead, just on hiatus. Will resume if there is interest.

Well, sign me up to a Protestant France (ditto for Scotland as well). Just need a Protestant Bohemia and my wishlist for Europe c. 1600s is pretty much complete.

Not wanting protestant Ottomans?!Well, sign me up to a Protestant France (ditto for Scotland as well). Just need a Protestant Bohemia and my wishlist for Europe c. 1600s is pretty much complete.

Not wanting protestant Ottomans?!

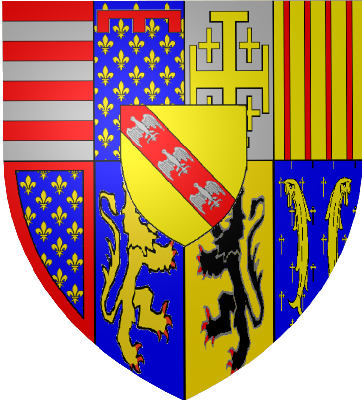

Nice to have you back, Direwolf! This alternate French civil war was a good read, and definitely seems like a plausible alternate path for the country to take in the 16th century. Looking forward to the Habsburg succession crisis that was foreshadowed.

I wonder how much these religion changes will form the alliance making of the continent. gonna be interesting to see.