Maybe Mr. Ross will be remembered as a successful gunsmith (or at least bullet-smith?) ittl

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."We're still very well within the bounds of OTL.Maybe Mr. Ross will be remembered as a successful gunsmith (or at least bullet-smith?) ittl

Last edited:

Only technological difference here so far is the decision to skip the upgrade of the .303 ammo. The chosen new ammunition and design of the new rifle are both OTL.We're still very well within the bounds of OTL.

As in a topic of further updates? Yes, I do have further updates regarding them in store.Is France next after the peace talks in Scandinavia?

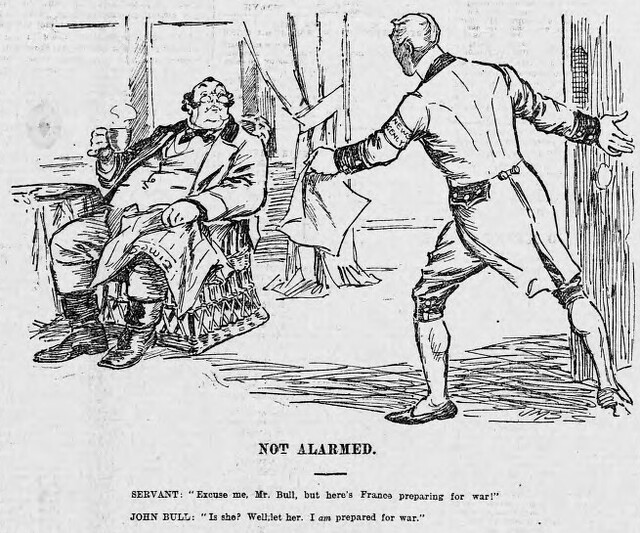

Chapter 255: The French Navy, Part I: "Mastodons!"

The French 1st-line battleships of 1897 were no less sad and peculiar designs than their foreign contemporaries.

On paper, the French fleet of 1897 was a naval force to be reckoned with. From 1886 to 1895, the French had launched nine fleet battleships, with three further placed on the stocks. This construction was part of a dedicated drive to prepare a 28 battleship-strong squadron, envisioned in the Programme of 1896.

Such grandiose plans were nothing new in French naval policy. The establishment of the Third Republic after the Franco-Prussian War had witnessed the declaration of a grand naval plan of 1872, calling for a massive expansion of the navy. A soon-to-be-familiar pattern then emerged: the plan proved untenable from a budget perspective, and was only partially completed, only to be swiftly followed by a new, equally grand and ambitious (and unrealistic) naval plan.

Nevertheless reforms and the additional construction had enabled the French to use their actual fleet to vastly expand their colonial empire during the last three decades of the 19th century.

The French naval designers had been busy. They were serving a state that constantly struggled to secure the funds to both maintain an army large enough to defend France on the Continent and to maintain a navy strong enough challenge the British at sea on their terms. Thus it had been the French who had for decades always eagerly pushed forward into every promising new naval technology, constantly seeking ways to change the rules of naval warfare.

This focus on new technologies, generational change in the French politics, and a renewed colonial rivalry with Britain due the new French colonial holdings had enabled Admiral Thèophile Aube to bring forth his personal ideas as the new leader of the French naval ministry in 1885. Section technique was created, and Émile Bertin, who would soon establish a reputation as a highly influential naval designer, had been tasked to head the new bureau in 1896.

When new political and economic developments made larger tonnages possible, the French ship designs were being standardised at last. Stopping the constant meddling and tinkering that had made every French battleship of being slightly different from another - the notorious "fleet of specimens" - now promised to make the future French fleet easier to both command and operate.

The past, current and future Ministers and the Conceils de la Marine were however soon engaged into a fierce debate, when the wider implications of the ideas of Aube became apparent.

Aube and other proponents of "la jeune Marine" viewed the existing French battleship fleet as unfit for war. The defenders of status quo were willing to point out that these "Cathedrals of the sea" were certainly far from perfect. Their main flaw was that they were top-heavy to the point of being potentially unstable with their excessive superstructures. But despite being mocked as "floating hotels" by their critics, their armor protection and armament were on par with the other contemporary battleship designs.

But Aube was not after better battleships. The admiral and other proponents of their novel, markedly anti-British naval doctrine had in mind something completely different.

Last edited:

Chapter 256: The French Navy, Part II: An Absolute Impossibility

The premise of the new strategy had been simple enough.

Modern torpedo, a new weapon system in naval warfare, posed a new threat to heavy battleships of old. Suddenly it seemed possible for any type of naval vessel to inflict massive damage to previously impervious battleships. This made the old tactic of a close naval blockade extremely risky, as new fast attack craft - torpedo boats - and even more novel new warships - submersibles and submarines - could use the new weapon to ambush battleships.

Building from this idea, the French naval doctrine sought to turn British strengths into weaknesses.

The French navy would build a string of fortified naval bases from her Channel coast ports at the continent all the way to Africa, Asia and Pacific. Torpedo boats defending these fortresses would then rapidly sortie against any hostile fleet attempting to blockade them, rendering close blockades impossible and keeping these coaling stations open for long-ranged French cruisers. These ships, in turn, would be able to wreak havoc in the shipping lines vital for the British trade, sinking and capturing ships at will. The French army would guard the French coast against enemy incursions.

With her long shipping routes exposed to merciless raiding and her home waters under constant threat, the British would be powerless to prevail.

The Jeune Ecole had numerous opponents in the French naval and political establishment from its start in the 1880s. They promoted the validity of the concept of a battleship-centered fleet located at home waters, with a reduced commitment to overseas possessions.

The doctrinal debate was also partially a discussion about the navy itself. The French naval force was not nicknamed "La Royale" only because of a street address - the fleet still proudly upheld conservative Catholic traditional values, and thus served as a useful arena for the cultural struggles between radicals and conservatives of the Third Republic.

While the colonial lobby wanted to secure more overseas stations, battleship proponents wanted to defend the status quo and the radicals wanted to use the new doctrine to attack the inherent conservatism of the Navy as an institution, it was hardly surprising that the war scare brought along by the Fashoda incident caught the French fleet by surprise.

When the British fleet was mobilised in late 1898 and Salisbury refused to even call the following diplomatic exchange negotiation, the French political elite was devastated to hear the reality of a navy that was on paper only second to the British in strength. The naval staff had to confirm that the French lacked a definitive campaign plan, and that the Navy was too plagued with material and organisational difficulties to be able to meet the Royal Navy with any chance of success.

The Navy was simply in no position to sustain a war against Britain, period. It was an absolute impossibility, even with Russian help - which would not be forthcoming in months even in the best-case scenario because of the ice conditions. The French society was luckily distracted by the latest turn of the Dreyfus Affair, and this turn of events enabled the French diplomats to climb down from the escalation ladder without a fuss (and without completely losing face.)

Each previous French naval bill had been an attempted compromise between the three factions, providing for the construction of battleships, coastal defence ships, torpedo boats, cruisers and dedicated station ships. These plans were ultimately too ambitious for the French budget, and the constant shifting of priorities in line with power struggles over construction plans and reforms of the naval bureaucracy meant that little construction was actually completed. Ships had languished for long periods on the ways, victims of funding difficulties and the use of naval construction as a means to promote full employment of yard workers no matter the cost or a pre-set timetable.

To make matters worse, neither the battleship proponents or the radicals had been willing to spent money on colonial defence, and in 1898 it had been painfully obvious that the perfidious Albion was once again in a position where they could rip the entire French colonial empire apart should they wish to do so.

The British had not been idle.

They had seen what the French had had in mind, and had met the challenge by altering their current designs and then engaging in massive production to thwart any potential competition.

The Royal Navy had already set the pattern for the pre-dreadnought battleship with an all-steel construction, draught engines, a main armament of four guns in twin mounts, one forward and one aft, with secondary guns mounted along the broadside in 1882 by launching the HMS Collingwood.

The basic design had been greatly improved at the end of the decade with the Royal Sovereigns: they were faster, featured guns in covered barbettes, and first and foremost had an increased number of quick-firing guns on board to deal with torpedo boats.

Culminating to HMS Majestic, a class that ultimately included a massive 37 ships, the Royal Navy kept her battle line both up to date and more numerous than any would-be competitor at the beginning of the century.

Just to drive the point further home, the British had also built more armored and protected cruisers in the ten-year span of 1890-1900 than it had done during the previous two decades combined. Purpose-built to hunt down French commerce raiders, the cruisers were complemented by a completely new ship class - torpedo boat destroyers, a class of ship designed specifically to screen larger fleet units from torpedo boat attack, armed with quick-firing guns and built for speed.

These new ships were also employed with a sound naval strategy, observational blockade, which the impressed French labelled système Ballard after its perceived inventor. The Royal Navy had actively wargamed a naval war with France, and adjusted her tactics and ship designs accordingly.

After Fashoda it was clear that the French would have to come up with a new plan - or any actual plan at all - to meet the British challenge.

Chapter 257: The French Navy, Part III: Something For Everyone

Defeat is an orphan, as the old saying goes. But being placed in a perceived position of peril can also make people to put aside their differences to survive. In the case of French, the old political divisions over naval issues from the 1890s were swept away overnight by the aftermath of Fashoda.

By 1900, every person who had a say in French naval policy agreed that urgent change was needed. The French retreat from Fashoda forced a general reappraisal of French diplomatic and military strategy, centered around a reevaluation of the navy.

The critics of Jeune Ecole rushed in like the glorified torpedo boat flotillas. All ships were now faster than before. British battleships were armed with their own quick-firing guns, and escorted by new torpedo-boat destroyers and light cruisers.

Even the Germans were now building new warships in a determined drive to seize control of the North Sea from the French and British alike. The French planners felt that Germany, with her small and insignificant overseas empire, would be less vulnerable to commerce raiding. But unlike the menacing Royal Navy, the Italian, German and Austrian fleets of the Triple Alliance were still small enough for the French to try and build against.

Taking advantage of the national outrage of Fashoda, Jean-Louis de Lanessan, in office from 1899 to 1902, led the creation of the first naval program formally signed into law in nearly half a century.

Just like Éduard Lockroy who preceded him, de Lanessan actively ignored the Jeune École as a strategic alternative.

Waldeck-Rousseau ministry, concerned with France's naval and colonial weakness, sought to address all aspects of the maritime security of France with a set of five bills. Once again the goals were ambitious and grand: new warships, improved arsenals and port facilities both in metropolitan France and overseas, improved colonial defences, and new extended overseas submarine cable network.

The cost was originally set at one milliard francs , to be financed over a period of eight years.

And for once, for the first time since Hamelin and Dupuy de Lôme’s Programme of 1857, France now had both an actual parliamentary acceptance and secure funding for a major naval programme. The resulting Programme of 1900 focused on the battlefleet, at the expense of coastal defence. Based on the ideas of Admiral Fournier, the plan called for a single fleet, stationed in European waters and consisting of battleships and large cruisers, capable of being used either against Britain or Germany.

Jeune Ecole ideas were not completely ignored either. By sending out commerce raiders the French fleet would cause enough damage to British shipping to force the Royal Navy to blockade French ports, bringing them within the reach of French torpedo boats. The main French fleet would maintain an active defensive posture, thus wearing down the British while seeking an opportunity for a decisive battle.

The new battleships would be larger, over 14 000 tons from the previous 12 000. The question of standardization was also now finally addressed: henceforth the combat fleet would include only three types of ships: battleships, armoured cruisers, and destroyers. Submarines and torpedo boats would take care of coastal defence.

The colonial overseas stations were relegated to use cast-offs from the combat fleet, with obsolete ships and few specialised gunboats maintaining the French presence outside her home waters.

The plan was sound, but it had only truly gotten underway when the results of the 1902 legislative election arrived. Waldeck-Rousseau, contemplating his ailing health and pleased with the success of the Left, announced that he was leaving office. It would be Émile Combes and his Radicals who would form the new Cabinet, and take over the Naval Ministry.[1]

1: And we're approaching our POD here, since so far everything else has been 100% OTL.

By 1900, every person who had a say in French naval policy agreed that urgent change was needed. The French retreat from Fashoda forced a general reappraisal of French diplomatic and military strategy, centered around a reevaluation of the navy.

The critics of Jeune Ecole rushed in like the glorified torpedo boat flotillas. All ships were now faster than before. British battleships were armed with their own quick-firing guns, and escorted by new torpedo-boat destroyers and light cruisers.

Even the Germans were now building new warships in a determined drive to seize control of the North Sea from the French and British alike. The French planners felt that Germany, with her small and insignificant overseas empire, would be less vulnerable to commerce raiding. But unlike the menacing Royal Navy, the Italian, German and Austrian fleets of the Triple Alliance were still small enough for the French to try and build against.

Taking advantage of the national outrage of Fashoda, Jean-Louis de Lanessan, in office from 1899 to 1902, led the creation of the first naval program formally signed into law in nearly half a century.

Just like Éduard Lockroy who preceded him, de Lanessan actively ignored the Jeune École as a strategic alternative.

Waldeck-Rousseau ministry, concerned with France's naval and colonial weakness, sought to address all aspects of the maritime security of France with a set of five bills. Once again the goals were ambitious and grand: new warships, improved arsenals and port facilities both in metropolitan France and overseas, improved colonial defences, and new extended overseas submarine cable network.

The cost was originally set at one milliard francs , to be financed over a period of eight years.

And for once, for the first time since Hamelin and Dupuy de Lôme’s Programme of 1857, France now had both an actual parliamentary acceptance and secure funding for a major naval programme. The resulting Programme of 1900 focused on the battlefleet, at the expense of coastal defence. Based on the ideas of Admiral Fournier, the plan called for a single fleet, stationed in European waters and consisting of battleships and large cruisers, capable of being used either against Britain or Germany.

Jeune Ecole ideas were not completely ignored either. By sending out commerce raiders the French fleet would cause enough damage to British shipping to force the Royal Navy to blockade French ports, bringing them within the reach of French torpedo boats. The main French fleet would maintain an active defensive posture, thus wearing down the British while seeking an opportunity for a decisive battle.

The new battleships would be larger, over 14 000 tons from the previous 12 000. The question of standardization was also now finally addressed: henceforth the combat fleet would include only three types of ships: battleships, armoured cruisers, and destroyers. Submarines and torpedo boats would take care of coastal defence.

The colonial overseas stations were relegated to use cast-offs from the combat fleet, with obsolete ships and few specialised gunboats maintaining the French presence outside her home waters.

The plan was sound, but it had only truly gotten underway when the results of the 1902 legislative election arrived. Waldeck-Rousseau, contemplating his ailing health and pleased with the success of the Left, announced that he was leaving office. It would be Émile Combes and his Radicals who would form the new Cabinet, and take over the Naval Ministry.[1]

1: And we're approaching our POD here, since so far everything else has been 100% OTL.

Correct me if I'm wrong but the POD is toward the tail-end of the Dreyfus Affair? I do believe he's getting pardoned by President Loubet. Could we safely assume that the Bloc De Gauches is focusing on its anti-clerical campaign and is purging the army of royalist and catholic officers? I do believe there was another huge scandal around this; specifically around the Freemasons.

I've covered this part c. 9 years(!) ago: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...th-century-history.272417/page-2#post-7537764Correct me if I'm wrong but the POD is toward the tail-end of the Dreyfus Affair? I do believe he's getting pardoned by President Loubet. Could we safely assume that the Bloc De Gauches is focusing on its anti-clerical campaign and is purging the army of royalist and catholic officers? I do believe there was another huge scandal around this; specifically around the Freemasons.

The situation of France is also covered in further detail here: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...-century-history.272417/page-35#post-20829825

and here

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...th-century-history.272417/page-7#post-9304258

Last edited:

And yes, the Dreyfus trial will go as per OTL. We'll get to the scandal part, since there wasn't only one, but several involving both the Navy, Army, the politicians - and the Masonic lodges.Correct me if I'm wrong but the POD is toward the tail-end of the Dreyfus Affair? I do believe he's getting pardoned by President Loubet. Could we safely assume that the Bloc De Gauches is focusing on its anti-clerical campaign and is purging the army of royalist and catholic officers? I do believe there was another huge scandal around this; specifically around the Freemasons.

Chapter 258: The French Navy, Part IV: Document 450

Émile Combes entered office with a firm intention to mostly ignore the Navy. The Dreyfus affair was dividing the nation and pulling political attention towards the Army. The political aspirations of the new French governing coalition were firmly anti-clerical, and thus the Navy, a known stronghold of monarchists and conservatives, was more of a collateral target of opportunity rather than main target of reforms for the new cabinet.

The initial idea of Combes was to appoint a Parisian Radical to the task. Camille Pelletan, an archivist by training, had thirty years of party seniority in his resume, and seemed as good appointment as anyone else available. The fact that he had a reputation as a firm supporter of the already disgraced Jeune Ecole did not really interest Combes. Pelletan had in mind sweeping reforms of the recruitment and structure of the Navy, but this old-style neo-Jacobin never got the chance to leave his radical imprint to the French Navy.

The Dreyfus affair was not the only scandal that drew major headlines during the tumult of year 1900.

As the Boxer War shook the international financial markets, Jules Bizat, a dutiful French banking official, had taken renewed professional interest to the personal finances of Thérèse Humbert.[1]

The famous Parisian socialite had been a target of persistent press war by Le Matin whose owners were convinced that Humbert was a dangerous fraud and a con artist instead of a wealthy heiress. As her creditors sued Humbert after Bizat had discovered major inconsistencies from her personal finances, Humbert fled the country. The scandal hit the forming Combes government in 1902 by surprise. Gaston Calmette, editor of Le Figaro, was determined to deter Pelletan from becoming the new Naval Minister.

The attack article from May 25th would have had little impact in itself - Pelletan had many political enemies - but for the fact that the newspaper claimed to hold a document linking Pelletan to the Humbert case.

This was indeed the case. A copy of a letter sent by Armand Parayre, one of the suspects, to Pelletan, asking the latter to intercede with the Minister of Justice Vallé to ensure that Parayre would avoid prosecution. In the letter Parayre reminded Pelletan that he had handed Pelletan "a considerable sum" as a reward for a speech Pelletan had held at the Chamber of Deputies, praising the Humbert family for producing excellent republicans and condemning the accusations against their finances as false rumours. The newspaper also had photostat of a registered-mail receipt for the Parayre letter, showing that it had been logged into the Ministry of the Navy as document 450.[2]

Pelletan first tried to say that he had not seen the letter at all, then hid from the reporters for a few days, and appeared back to public with his chef de cabinet, Tissier, to claim that this letter must have somehow disappeared at the internal mail. They were also all too anxious to deny the allegation that Parayre would have ever given Pelletan "any 30 000 FF", or that there had been any attempt to influence the Ministry of Justice not to persecute Parayre. Le Figaro was not the only media to gleefully point out that Parayre letter had only spoken about "a considerable sum" of money instead of 30 000.

Combes, determined to hold his shaky majority together to ensure the passage of his key political aim, the legislation separating the Church and State, had no reason to jeopardize his main goal by defending a single minister. Pelletan had to resign before even taking office.[3].

1. In OTL this part of the decades-long scandal started a bit later, but for the exactly same reason.

2. In OTL this letter was written in September 1902, and dutifully logged as Document 706.

3. In OTL Combes defended Pelletan, who did not resign. Here the war in China and the French intervention to it has made Combes much more cautious about the unity of his government, and the earlier timing of the scandal makes ditching Pelletan potentially much easier. In OTL Pelletan was nicknamed "the Wrecker", and his work as the Naval Minister is widely considered near-disastrous for the procurement, readiness and morale of the French Navy.

Last edited:

First of all, thanks for the feedback. The TL has certainly gained volume during the years.A few questions: Do you intend to talk about colonial development (infranstructure, resources etc) ? And explore how the changes that already occured afect latin america?

Colonial history is something I might stumble upon eventually, but Latin America has sadly received bit of a Paradox Interactive treatment from this TL so far, aside from the quick foray to Venezuela.

Even the US has been rather sidelined from the general focus of the story so far, namely because China and the Ottoman Empire were much more central to general European Great Power politics of the day.

But as the butterflies flap on, I will have to eventually cover the divergences elsewhere in the world as well.

For Latin American content, I warmly recommend KingSweden24's Cinco de Mayo.Well if and when you tackle latin america I imagine that one of the first countries would be Mexico, given its relationship with Germany at the time. Who knows, maybe the butterflies are strong enough to benefit Huerta and Germany.

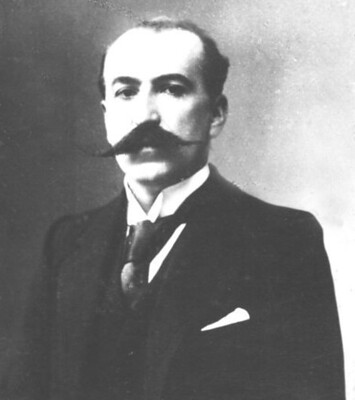

Chapter 259: The French Navy, Part V: Le père de la marine

French parliamentary politics were in flux at this era, and therefore finding new ministers after their predecessors had been ousted by one scandal or another was rather routine business. What Combes was after in 1902 was a person who had to meet a specific criteria:

- acceptable political credentials among the Bloc des gauches (in practice at least a republican pointcarist or someone from further left)

- anticlericalist

- Dreyfusard

- preferably someone with former ministerial experience

- even more preferably someone with a reputation of actually getting things done!

This check-list of demands narrowed the number of potential candidates down considerably.

Most importantly Combes wanted to swiftly proceed with the main domestic policy agenda of his new government, and thus the new minister had to be found rather quickly.

And thus the name of a man who had vigorously promoted the key Radical agenda of reform was brought up. He had steered through a comprehensive reform bill of education during the previous Waldeck-Rousseau government as the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts (the second time he held this office) in the face of determined conservative opposition. He was also a former Minister of the Interior, with a reputation of a firm Dreyfusard.

A part of the same new generation of prominent future politicians as Delcassé, Poincaré and Barthou, he belonged to the ranks of men who had risen to prominence after the Panama Scandal had swept away many old faces from the lists of the French deputies.

He was a skilled orator, renowned for his poetic rhetoric, and had gained a ministerial position before turning 40 during the 1890s. And while he had associated himself with the most famous poets and musicians of the day, he was also the chairman of the Association des Cadets de Gascogne, a group of southwestern French politicians who promoted their mutual careers with the best of their ability.

And most importantly, he did not turn down the offer of taking office in a position that had reputation of being rather windy after the Fashoda fiasco.

Never shy to challenges, he privately still recalled how he had originally wanted to become a naval officer before his mother had convinced him to study law instead.

Thus Combes had found a suitable replacement, and named Georges Leygues as the Minister of Navy to his new cabinet in autumn 1902. The foundations of the future of French navy were thus laid out seemingly at random, without any pomp and circumstance.

So is Clemenceau heading back into politics or is he going to stay in journalism? If I’m not mistaken he was almost always a newspaper editor/journalist when he wasn’t in parliament. I wasn’t sure if he regained his seat in the 1902 elections, especially after the Panama Canal scandal

Reference to him in the previous post was intentional, but as for now he is not a central figure.So is Clemenceau heading back into politics or is he going to stay in journalism? If I’m not mistaken he was almost always a newspaper editor/journalist when he wasn’t in parliament. I wasn’t sure if he regained his seat in the 1902 elections, especially after the Panama Canal scandal

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: