You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Chapter 17: Yamagata-Muraviev Agreement

Yamagata-Muraviev Agreement

“Though I may exhaust

my aging body

I will not falther

until my mission is achieved.”

Yamagata Arimoto, 1896.

After the new Chinese government had managed to ensure the nominal Chinese territorial integrity by concluding the Russo-Chinese Agreement regarding Manchurian railways and commercial interests alongside the wider settlement of the Boxer War, the next major change in the diplomatic geography of Far East took place in the autumn, when Yamagata Arimoto made an official state visit to Russia in September 1901.

The visit had a lot of symbolic value in Japanese domestic politics, as this wasn’t the first time when the old warrior journeyed abroad, and the second time he was sent to Russia. In 1896 Yamagata Arimoto had been appointed minister plenipotentiary and instructed to attend the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II Moscow, in company with Prince Fushimi who had been selected as Japan’s formal representative. Yamagata had been sent on a mission, with the task of negotiating an agreement with Russia regarding the future of Korean peninsula. Originally the task had been set for Itō, but opposition to his appointment had made him to nominate Yamagata to the task. Yamagata had been accompanied by army officers, representatives from the Foreign Office and the Imperial Household ministry. After touring the United States, France and Germany the delegation had arrived to Moscow with the task of striking a deal that would stabilize the situation in Korea and promote law and order. The result of this visit had been the Yamagata-Lobanov Agreement, where both powers agreed to recognize independence of Korea, guarantee foreign loans for internal reforms and support the Korean monarchy in maintaining order and carrying out reforms. The treaty had also included secret clauses that degreed that both parties could dispatch troops to maintain their lines of communication, and secure order in the peninsula in times of major unrest.[1]The agreement had benefitted both sides at the time, but five years later it was painfully obvious that it had failed to address the friction and rivalry between the two powers in the Far East.

Now Prime Minister Itō wanted to solve this matter and secure the interests of Japan in Far East. Together with Yamagata the two old genrō leaders agreed that diplomatic efforts to strike a deal with Russia could still work - after all, only five years earlier Yamagata himself had recommended efforts to establish a Russo-Japanese coalition.[2] Together with his Foreign Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu Itō was able to convince his old friend and rival to go - knowing well that Yamagata was one of the few statesmen in Japan whose personal authority and charisma would give the endeavour enough prestige to mute the anti-Russian critics to such approaches. In exchange Itō promised Yamagata to pursue the negotiations with British diplomats, regardless of the ultimate results of his visit.

The official visit took place after a summer of busy diplomacy between Tokyo and St.Petersburg. After Count Muraviev had ordered Ambassador Izvolski to secure a treaty with Russia, the withdrawal of Russian forces from southern Manchuria and the end of Boxer insurgency in Northeastern China had a calming effect to the the diplomatic tensions in the Far East. Yamagata was well informed of these events, and met with his old friend, Colonel Vogak who visited Tokyo on his way back from negotiations in Peking. Konstantin Ippolitovich Vogak had been appointed to Russian military attaché in Japan 1893, and had subsequently served as observer during the Sino-Japanese War. He had returned home to Russia with conviction that Japan posed a formidable challenge to Russian interests in the Far East, and that she would fight for her position as a regional power and to defend her interests in Asia if needed to. His final report reflected this view:

“We should very, very seriously take the Japanese army into account. I think it my duty to report in a military respect that Japan is positively the strongest state in the Far East, including Russia. Its 60 000-man army, which can be expanded almost three times on mobilization, is worthy of attention both in terms of organization and personnel. This is the opinion of all people who have observed this army. And one should not forget Japan's very good navy, too...I think that we have a dangerous neighbour in Japan, which we should very much take into account in the future...In the face of Japan a new force has been born, which will have great influence upon the destinies of the Far East."

His successor, Nicholas Ivanovic Ianzhul, had similar opinion.[3] He wasn’t alone with his views - the Russian naval attaché Lieteunant I.I. Chagin had concluded a report on the Japanese Navy to the Naval Main Staff in October 1900 by stating that:

"It is very, very difficult and rather impossible to fight with Japan in her waters. For such a war the attacking side should have very large naval and ground forces. For the time being, there is no country in the East with such forces."[4]

Upon returning to St.Petersburg, Vogak wrote a memorandum where he critiqued Russian Far Eastern diplomacy after the Sino-Japanese War. Vogak boldly claimed that failure to assure her security against a strong Japan whose "military successes were not fully recognized" had put Russia into a collision course with a rising power, and to avoid it Russia should give "Mikado's Empire a corresponding place in solving the problems of the Far East...Avoidance of war in the Far East is a primary task of state policy."[5]

At the same time when Count Muraviev answered these criticisms by stating that he was actively trying to alter the status quo, other figures in court circles made their views known to the Autocrat. Financial Minister Witte was especially eager to secure his beloved railway empire from further damages and disturbances. According to him Russia “sought nothing” from Korea, and should be quite content on acknowledging Japanese interests in the peninsula.

For War Minister Kuropatkin, the gravest military danger to Russia always emanated from Europe; therefore, it was in her interests to avoid an arms race with Japan in Korea and Manchuria, as it would be essentially impossible for Russia to permanently devote an increased part of its military budget to the Far East. Kuropatkin was therefore stating that militarily Russia should remain focused on securing the safety of vital Trans-Siberian railroad, and stated that Vladivostok was entirely sufficient port for Russian naval needs in the Pacific.[6]

After negotiating with Japanese diplomats through the summer, Izvolski reported to St.Petersburg that the Japanese attitude towards Korea called for Russia to “recognize Japan’s freedom of action in its political, industrial and commercial aspects and her exclusive right to help Korea by giving her advice and military aid” When the triumvirate discussed these early proposals, Muraviev obtained the views of Witte and Kuropatkin and passed them together to the czar. On his memo of the subject Kuropatkin commented: “We have decided to evacuate our troops from Manchuria...Even if we keep the northern parts of the region in certain state of dependence, we have every reason to believe that a break with Japan will be avoided. Consequently our new agreement with Japan ought not to be bought at too high a price...we should use every means to hinder Japanese forces being moved to Korea and stationed there permanently.” After Nicholas II had viewed these memorandums, Muraviev obtained his approval to formulate a counter-draft. It covered:

[1] All OTL.

[2] And without Russian diplomatic gaffes that took place in OTL, Yamagata is less sceptical.

[3] In OTL Ianzhul was replaced in 1989 to address family matters. His successor, Colonel Gleb Mikhailovich Vannovskii, who based his negative views on Japanese military capabilities entirely on speculation and contemporary Russian books about Japan. Here Ianzhul has no need for such leave - he stays on his job, and his reports convince General Kuropatkin of the capabilities of Japanese military, whereas in OTL his successor managed to portray a negative image of Japanese capabilities.

[4] All report texts are OTL. There were keen Russian observers who had realistic views about Japanese military capabilities - but in OTL they were sidelined or ignored by key figures in the court.

[5] OTL excerpts from a report Vogak wrote in spring 1902 in his schemes with Admiral Abaza and Bezobrazov. Here his tasked to work with the situation in China due his former experience as a military attaché in Peking, while Bezobrazov is in Geneve, seeing his sick wife who was living there - and whose health has taken a sudden turn to the worse compared to OTL.

[6] In OTL 1903 Kuropatkin devised a memorandum where he proposed Nicholas II that Russia should return to China of the Kwantung peninsula with Port Arthur and sell South Manchurian Railroad to China while directly annexing northern Manchuria.

[7] Based on the OTL counter-proposal Lamsdorf devised in December 1901 by the authorization of Nicholas II. The list misses two points, one regarding “menacing military installations” that would hinder movement through the Korean Straits, and second warming the Japanese army of ever crossing a neutralized zone in Russian the border. Reasons for their omission are better cooperation within the still-intact triumvirate and more realistic attitude of Kuropatkin + absence of Bezobrazov and his influential Far Eastern naval lobby.

“Though I may exhaust

my aging body

I will not falther

until my mission is achieved.”

Yamagata Arimoto, 1896.

After the new Chinese government had managed to ensure the nominal Chinese territorial integrity by concluding the Russo-Chinese Agreement regarding Manchurian railways and commercial interests alongside the wider settlement of the Boxer War, the next major change in the diplomatic geography of Far East took place in the autumn, when Yamagata Arimoto made an official state visit to Russia in September 1901.

The visit had a lot of symbolic value in Japanese domestic politics, as this wasn’t the first time when the old warrior journeyed abroad, and the second time he was sent to Russia. In 1896 Yamagata Arimoto had been appointed minister plenipotentiary and instructed to attend the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II Moscow, in company with Prince Fushimi who had been selected as Japan’s formal representative. Yamagata had been sent on a mission, with the task of negotiating an agreement with Russia regarding the future of Korean peninsula. Originally the task had been set for Itō, but opposition to his appointment had made him to nominate Yamagata to the task. Yamagata had been accompanied by army officers, representatives from the Foreign Office and the Imperial Household ministry. After touring the United States, France and Germany the delegation had arrived to Moscow with the task of striking a deal that would stabilize the situation in Korea and promote law and order. The result of this visit had been the Yamagata-Lobanov Agreement, where both powers agreed to recognize independence of Korea, guarantee foreign loans for internal reforms and support the Korean monarchy in maintaining order and carrying out reforms. The treaty had also included secret clauses that degreed that both parties could dispatch troops to maintain their lines of communication, and secure order in the peninsula in times of major unrest.[1]The agreement had benefitted both sides at the time, but five years later it was painfully obvious that it had failed to address the friction and rivalry between the two powers in the Far East.

Now Prime Minister Itō wanted to solve this matter and secure the interests of Japan in Far East. Together with Yamagata the two old genrō leaders agreed that diplomatic efforts to strike a deal with Russia could still work - after all, only five years earlier Yamagata himself had recommended efforts to establish a Russo-Japanese coalition.[2] Together with his Foreign Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu Itō was able to convince his old friend and rival to go - knowing well that Yamagata was one of the few statesmen in Japan whose personal authority and charisma would give the endeavour enough prestige to mute the anti-Russian critics to such approaches. In exchange Itō promised Yamagata to pursue the negotiations with British diplomats, regardless of the ultimate results of his visit.

The official visit took place after a summer of busy diplomacy between Tokyo and St.Petersburg. After Count Muraviev had ordered Ambassador Izvolski to secure a treaty with Russia, the withdrawal of Russian forces from southern Manchuria and the end of Boxer insurgency in Northeastern China had a calming effect to the the diplomatic tensions in the Far East. Yamagata was well informed of these events, and met with his old friend, Colonel Vogak who visited Tokyo on his way back from negotiations in Peking. Konstantin Ippolitovich Vogak had been appointed to Russian military attaché in Japan 1893, and had subsequently served as observer during the Sino-Japanese War. He had returned home to Russia with conviction that Japan posed a formidable challenge to Russian interests in the Far East, and that she would fight for her position as a regional power and to defend her interests in Asia if needed to. His final report reflected this view:

“We should very, very seriously take the Japanese army into account. I think it my duty to report in a military respect that Japan is positively the strongest state in the Far East, including Russia. Its 60 000-man army, which can be expanded almost three times on mobilization, is worthy of attention both in terms of organization and personnel. This is the opinion of all people who have observed this army. And one should not forget Japan's very good navy, too...I think that we have a dangerous neighbour in Japan, which we should very much take into account in the future...In the face of Japan a new force has been born, which will have great influence upon the destinies of the Far East."

His successor, Nicholas Ivanovic Ianzhul, had similar opinion.[3] He wasn’t alone with his views - the Russian naval attaché Lieteunant I.I. Chagin had concluded a report on the Japanese Navy to the Naval Main Staff in October 1900 by stating that:

"It is very, very difficult and rather impossible to fight with Japan in her waters. For such a war the attacking side should have very large naval and ground forces. For the time being, there is no country in the East with such forces."[4]

Upon returning to St.Petersburg, Vogak wrote a memorandum where he critiqued Russian Far Eastern diplomacy after the Sino-Japanese War. Vogak boldly claimed that failure to assure her security against a strong Japan whose "military successes were not fully recognized" had put Russia into a collision course with a rising power, and to avoid it Russia should give "Mikado's Empire a corresponding place in solving the problems of the Far East...Avoidance of war in the Far East is a primary task of state policy."[5]

At the same time when Count Muraviev answered these criticisms by stating that he was actively trying to alter the status quo, other figures in court circles made their views known to the Autocrat. Financial Minister Witte was especially eager to secure his beloved railway empire from further damages and disturbances. According to him Russia “sought nothing” from Korea, and should be quite content on acknowledging Japanese interests in the peninsula.

For War Minister Kuropatkin, the gravest military danger to Russia always emanated from Europe; therefore, it was in her interests to avoid an arms race with Japan in Korea and Manchuria, as it would be essentially impossible for Russia to permanently devote an increased part of its military budget to the Far East. Kuropatkin was therefore stating that militarily Russia should remain focused on securing the safety of vital Trans-Siberian railroad, and stated that Vladivostok was entirely sufficient port for Russian naval needs in the Pacific.[6]

After negotiating with Japanese diplomats through the summer, Izvolski reported to St.Petersburg that the Japanese attitude towards Korea called for Russia to “recognize Japan’s freedom of action in its political, industrial and commercial aspects and her exclusive right to help Korea by giving her advice and military aid” When the triumvirate discussed these early proposals, Muraviev obtained the views of Witte and Kuropatkin and passed them together to the czar. On his memo of the subject Kuropatkin commented: “We have decided to evacuate our troops from Manchuria...Even if we keep the northern parts of the region in certain state of dependence, we have every reason to believe that a break with Japan will be avoided. Consequently our new agreement with Japan ought not to be bought at too high a price...we should use every means to hinder Japanese forces being moved to Korea and stationed there permanently.” After Nicholas II had viewed these memorandums, Muraviev obtained his approval to formulate a counter-draft. It covered:

1. Mutual guarantee of Korean independence.

2. Joint agreement not to use Korean territory for military objectives.

3. Russia admits the following items to Japan:

a.) That Japan possesses freedom of action in Korea in respect of industrial and commercial connections

b) That Japan after priour consultations with Russia has superior rights to help Korea with active support and thus make her conscious of obligations inseparable from better government

c) Russia includes in the above military help if necessary to quell disturbances prejudicing peaceful relations between Korea and Japan.

4. Former agreements are completely cancelled by this agreement.

5. Japan acknowledges Russia’s preferential rights in northern Manchuria adjoining the Russian border and undertakes not to infringe Russia’s freedom of action in that area.

6. On occasions prescribed in article 4 Japan undertakes not to send forces beyond the number which the situation dictates and to recall troops immediately the mission has been achieved.[7]

When the Russian reply was represented to Prime Minister Itō, he summoned his cabinet together. “If Japan and Russia will guarantee jointly the independence of Korea, desisting from using Korean territory or any portion of it for any purpose of military strategy, Russia will acknowledge Japan’s special freedom of action in Korea in matters industrial, commercial and political and in such military measures as are needed for the suppression of civil disturbances and the like. Today represents a suitable chance of making an agreement with the only other country in the world which has interests in Korea. I heartily recommend an amicable agreement with Russia, which would become impossible after conclusion of any kind of agreement with Britain.” After consulting the British diplomats - who were relieved to note that Russia was seemingly sincere in her attempts to defuse tensions in Manchuria and Far East - Japanese leadership moved swiftly. Yamagata arrived to St. Petersburg on 20th of September 1901, and was received most cordially by the czar at Tsarskoye Selo on the following day. He was presented with the Gold Cordon of St Alexander Nevsky and urged by the czar to use the Trans-Siberial Railway for his eventual journey home. After visiting Nicholas II, Yamagata became a quest of Count Muraviev who also gave him and rest of the Japanese delegation a state reception. As the real negotiations had mostly been concluded well in advance in Tokyo, the signatory ceremony took place on 22nd of September 1901. With the conclusion of Anglo-Japanese alliance in following January, Yamagata Arimoto and Itō Hirobumi secured their place in history as the statesmen that guided Japan towards 20th century with shrewd diplomacy that lifted the island nation from isolation to a major power with minimal bloodshed and grim determination. For Russian government, the settlement in Far East enabled Muraviev and Kuropatkin to focus on pursuing their strategic goals in European politics.

[1] All OTL.

[2] And without Russian diplomatic gaffes that took place in OTL, Yamagata is less sceptical.

[3] In OTL Ianzhul was replaced in 1989 to address family matters. His successor, Colonel Gleb Mikhailovich Vannovskii, who based his negative views on Japanese military capabilities entirely on speculation and contemporary Russian books about Japan. Here Ianzhul has no need for such leave - he stays on his job, and his reports convince General Kuropatkin of the capabilities of Japanese military, whereas in OTL his successor managed to portray a negative image of Japanese capabilities.

[4] All report texts are OTL. There were keen Russian observers who had realistic views about Japanese military capabilities - but in OTL they were sidelined or ignored by key figures in the court.

[5] OTL excerpts from a report Vogak wrote in spring 1902 in his schemes with Admiral Abaza and Bezobrazov. Here his tasked to work with the situation in China due his former experience as a military attaché in Peking, while Bezobrazov is in Geneve, seeing his sick wife who was living there - and whose health has taken a sudden turn to the worse compared to OTL.

[6] In OTL 1903 Kuropatkin devised a memorandum where he proposed Nicholas II that Russia should return to China of the Kwantung peninsula with Port Arthur and sell South Manchurian Railroad to China while directly annexing northern Manchuria.

[7] Based on the OTL counter-proposal Lamsdorf devised in December 1901 by the authorization of Nicholas II. The list misses two points, one regarding “menacing military installations” that would hinder movement through the Korean Straits, and second warming the Japanese army of ever crossing a neutralized zone in Russian the border. Reasons for their omission are better cooperation within the still-intact triumvirate and more realistic attitude of Kuropatkin + absence of Bezobrazov and his influential Far Eastern naval lobby.

Last edited:

Good to see it back- and interesting to see the probable avoidance of a Russo-Japanese War.

Good to see it back- and interesting to see the probable avoidance of a Russo-Japanese War.

According to my research the butterflies necessary to spirit that conflict away are not as large as one would expect in retrospect.

The more I researched, the more the history of the pre-war years felt like a TL where the writer worked hard to make all attempts of moderation and agreement to fail, and silenced all characters that could have changed the situation in the worst possible moments.

With this update the Far Eastern situation is largely resolved, for now. Focus of this TL will shift to Balkans.

interesting to see a switch of focus!

Dealing with the declining and changing old empires that actually caused most of the changes in fin de siècle international diplomacy and geopolitics is already one of the main themes of this TL.

I find it especially interesting since these themes are generally handwaved away or dealt with minor details, even in many otherwise really good TLs.

I find it especially interesting since these themes are generally handwaved away or dealt with minor details, even in many otherwise really good TLs.

I've done my homework regarding the Balkans, and now its time for another update poll. What would you like to read about next?

A. Russian and Austro-Hungarian foreign policy goals in the Balkans

B. Situation of Ottoman Albania and Macedonia in the beginning in of 1900

C. Foreign policy goals of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Romania

A. Russian and Austro-Hungarian foreign policy goals in the Balkans

B. Situation of Ottoman Albania and Macedonia in the beginning in of 1900

C. Foreign policy goals of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Romania

Chapter 18: Untamed and Unruly - the Albanian territories of Ottoman Balkans in first years of the 20th century

Untamed and Unruly - the Albanian territories of Ottoman Balkans in first years of the 20th century

“The soul of a slain man never rests till blood has been taken for it.”

Old Albanian proverb.

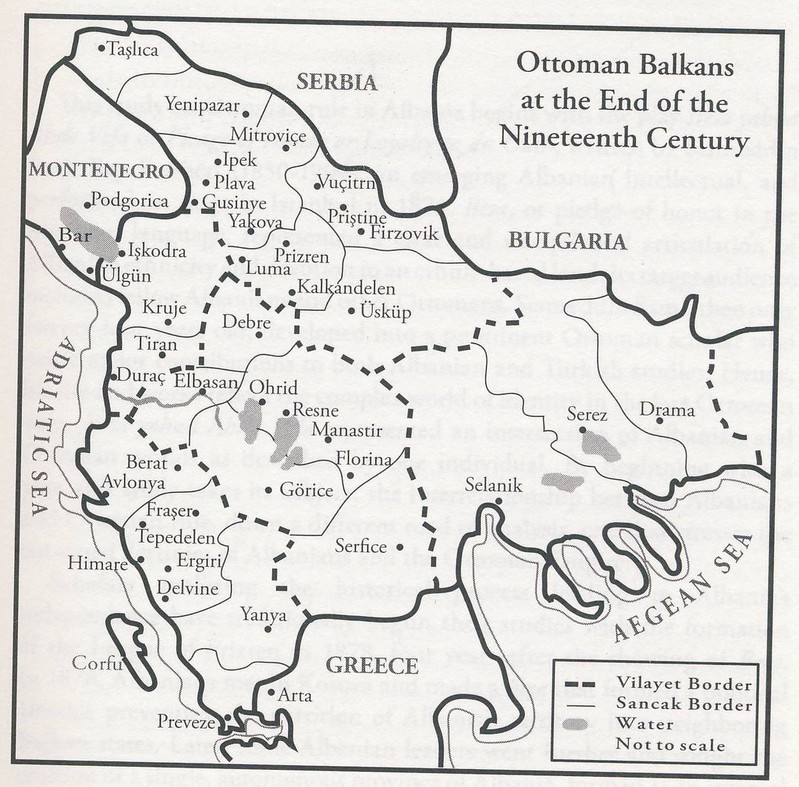

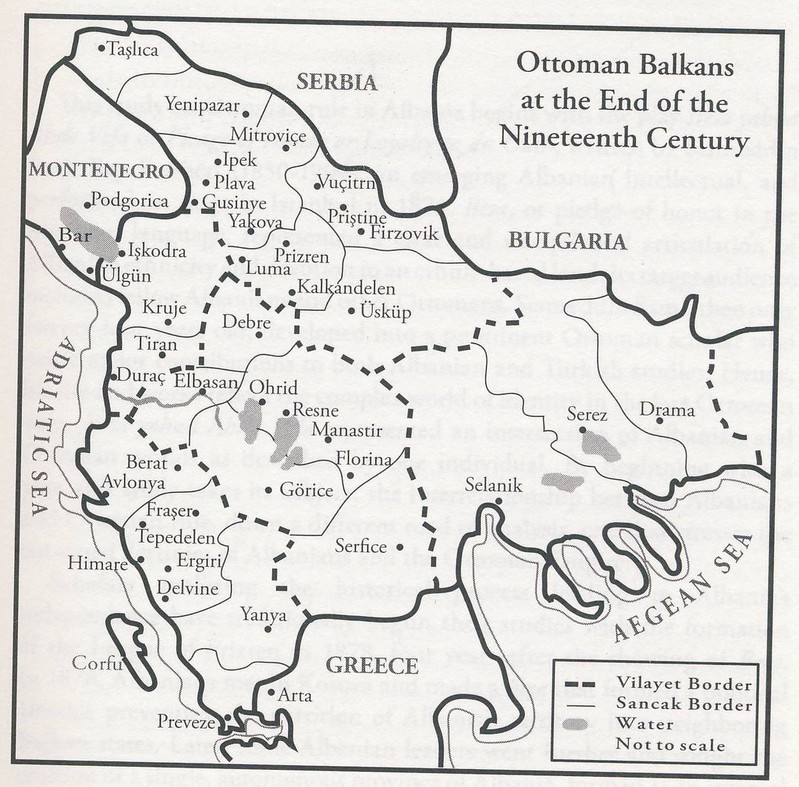

The Arnavudlar of Ottoman Balkan territories lived a culturally and politically divided life at the dawn of 20th century. Administratively the Albanian-majority areas of the Empire were at the vilayets of Iskodra, Kosova, Manastir and Yanya. Culturally the Albanians were divided into two distinct regions by the Shkumbi River, that separated the southern Tosks from northern Gegs. Toskalik, "the land of the Tosks", encompassed parts of Yanya and Manastir. Out of the two parts of Albanian lands the southern half was better connected to rest of the empire and world in general. The valleys of Tosks were open and fertile farmland, where a small elite of wealthy landowners, beys, kept rest of the population under their control and controlled most of the arable land as large estates. This landed elite of Tosk society had provided the Empire with several able viziers and generals during the centuries of Ottoman rule, and sought to preserve the status quo in the region as beneficial to their own priviledges. On the northern bank of Shkumbi was the northern half of Albanian territories. At the beginning of century Gegalik, "the land of the Gegs", was the wildest and most dangerous territory of whole Balkans - and considering the plight of Macedonia, that's quite of a statement in itself.

The wildest of Geg Albanians were the malisors (highlanders) who lived in the autonomous isolation in the mountainous highlands and adhered only to their own customary tribal justice, Law of Lek Dukandjin, that had been codified by a Norman prince who had ruled the region in 1460s. Religious practices were of secondary importance to tribal customs - several households had both Catholic and Muslim members, and some clans had the habit of keeping many wives and marrying the first woman in church and the others before an imam. Influence of Sufi order of Bektaşism had made wine-drinking a common habit among Muslim Albanians, and circumcision was unknown among malisors. Their sense of justice was Hammurabian - koka per köke - “a head for a head” was a central maxim that demanded families and whole clans to declare blood feuds known as gjakmarje against anyone who had wronged or killed their kinsmen. The severity of this law was far from empty boasting - Ottoman officials estimated that in northern Albanian territories as many as 19% of all deaths among Albanian males were murders committed in the name of gjakmarje - in Kosovo alone, 600 men died every year from a population of 50 000! Considering their violent culture, it is no wonder that the largest organizational unit that the mountain clans acknowledged was a tribal grouping known as a fis. Each fis was a territorial unit that controlled their own pastureland, and claimed descent from a historical ancestor - several fis could share common mythological forefathers, but were still considered distinct entities. A fis was headed by a standard-bearer, bayraktar, and largest tribes had several bayraktars.

Leaders in this hereditary position acted as arbitrators in disputes and led the fis in battle. To make important decisions involving the whole fis, the bayraktar had to summon the council of elders known as plak - decisions made by plak were binding on all members of the fis. Often the decisions involved a raid against southern lowlands, and controlling the mountain clans was something the Ottomans had never seriously attempted ever since they had gained control of the region several centuries ago. In day-to-day administration local violence, poverty, illiteracy and foreign intrigue sapped the energies of government officials who had been unlucky enough to be posted to Gegalik. To govern in Albanian territories, Sultan Abdülhamid II had settled for indirect means of building patronage networks by co-opting local clan chieftains, prominent landowning families and urban notables with government positions and other privileges, and by soliciting recruits for his palace guard from local tribes. Without a major threat, Albanians had for long remained internally divided and focused on their local matters and ever-present feuds. For authorities, the Albanians remained unruly subjects and strong potential allies - the combined military strength of Malisor tribes alone was estimated to be over 30 000 armed warriors, and Albanian territories had served as source of manpower for Ottoman armies for a long time.

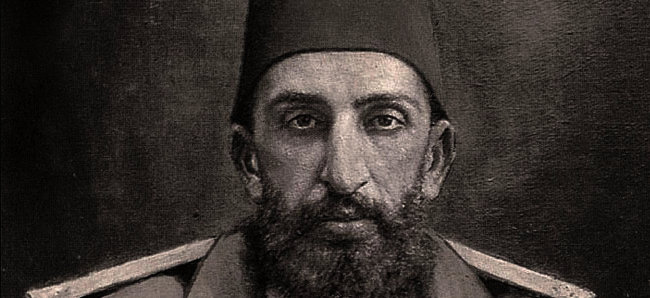

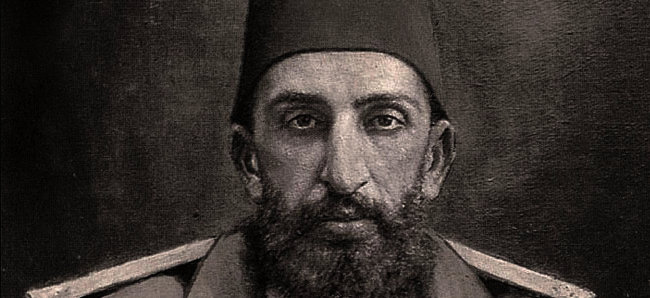

Recent defeats and loss of Albanian-majority territories to Greece and Montenegro had alarmed the Albanian leaders, and in 1881 they had already expressed their willingness and capacity to mobilize the common people of this restless region to public unrest and outright revolts against the Ottoman authority unless their demands for reforms and extended autonomy for Albanian lands would be met. The six-point program of the League of Prizen had demanded that no part of the Albanian territory should be incorporated to any other state, that the Albanian areas in the three vilayets should form one province, where Albanian officials would control the administration and justice system, and that a national police force would guard the internal stability of this new entity. The "Red Sultan" had initially sought to channel the Albanian national sentiment towards a more religious direction, but having lost control of the events he had dispatched the army to reassert direct Ottoman rule over the Albanian-populated vilayets. The legacy of these actions was still strong in 1900, when events on other side of the world begun to unravel the status quo the Major powers had asserted to the area with the Treaty of Berlin. Back in Ottoman Empire the thirty-two years of despotic rule of Abdülhamid II had created a whole new generation of reformists and revolutionaries, with many notable Albanians among them. As they were meeting one another in exile and secrecy and forming grassroot organizations aimed to topple the rule of the hated Sultan, none of them realized how quick and dramatic changes their homeland would soon experience.

“The soul of a slain man never rests till blood has been taken for it.”

Old Albanian proverb.

The Arnavudlar of Ottoman Balkan territories lived a culturally and politically divided life at the dawn of 20th century. Administratively the Albanian-majority areas of the Empire were at the vilayets of Iskodra, Kosova, Manastir and Yanya. Culturally the Albanians were divided into two distinct regions by the Shkumbi River, that separated the southern Tosks from northern Gegs. Toskalik, "the land of the Tosks", encompassed parts of Yanya and Manastir. Out of the two parts of Albanian lands the southern half was better connected to rest of the empire and world in general. The valleys of Tosks were open and fertile farmland, where a small elite of wealthy landowners, beys, kept rest of the population under their control and controlled most of the arable land as large estates. This landed elite of Tosk society had provided the Empire with several able viziers and generals during the centuries of Ottoman rule, and sought to preserve the status quo in the region as beneficial to their own priviledges. On the northern bank of Shkumbi was the northern half of Albanian territories. At the beginning of century Gegalik, "the land of the Gegs", was the wildest and most dangerous territory of whole Balkans - and considering the plight of Macedonia, that's quite of a statement in itself.

The wildest of Geg Albanians were the malisors (highlanders) who lived in the autonomous isolation in the mountainous highlands and adhered only to their own customary tribal justice, Law of Lek Dukandjin, that had been codified by a Norman prince who had ruled the region in 1460s. Religious practices were of secondary importance to tribal customs - several households had both Catholic and Muslim members, and some clans had the habit of keeping many wives and marrying the first woman in church and the others before an imam. Influence of Sufi order of Bektaşism had made wine-drinking a common habit among Muslim Albanians, and circumcision was unknown among malisors. Their sense of justice was Hammurabian - koka per köke - “a head for a head” was a central maxim that demanded families and whole clans to declare blood feuds known as gjakmarje against anyone who had wronged or killed their kinsmen. The severity of this law was far from empty boasting - Ottoman officials estimated that in northern Albanian territories as many as 19% of all deaths among Albanian males were murders committed in the name of gjakmarje - in Kosovo alone, 600 men died every year from a population of 50 000! Considering their violent culture, it is no wonder that the largest organizational unit that the mountain clans acknowledged was a tribal grouping known as a fis. Each fis was a territorial unit that controlled their own pastureland, and claimed descent from a historical ancestor - several fis could share common mythological forefathers, but were still considered distinct entities. A fis was headed by a standard-bearer, bayraktar, and largest tribes had several bayraktars.

Leaders in this hereditary position acted as arbitrators in disputes and led the fis in battle. To make important decisions involving the whole fis, the bayraktar had to summon the council of elders known as plak - decisions made by plak were binding on all members of the fis. Often the decisions involved a raid against southern lowlands, and controlling the mountain clans was something the Ottomans had never seriously attempted ever since they had gained control of the region several centuries ago. In day-to-day administration local violence, poverty, illiteracy and foreign intrigue sapped the energies of government officials who had been unlucky enough to be posted to Gegalik. To govern in Albanian territories, Sultan Abdülhamid II had settled for indirect means of building patronage networks by co-opting local clan chieftains, prominent landowning families and urban notables with government positions and other privileges, and by soliciting recruits for his palace guard from local tribes. Without a major threat, Albanians had for long remained internally divided and focused on their local matters and ever-present feuds. For authorities, the Albanians remained unruly subjects and strong potential allies - the combined military strength of Malisor tribes alone was estimated to be over 30 000 armed warriors, and Albanian territories had served as source of manpower for Ottoman armies for a long time.

Recent defeats and loss of Albanian-majority territories to Greece and Montenegro had alarmed the Albanian leaders, and in 1881 they had already expressed their willingness and capacity to mobilize the common people of this restless region to public unrest and outright revolts against the Ottoman authority unless their demands for reforms and extended autonomy for Albanian lands would be met. The six-point program of the League of Prizen had demanded that no part of the Albanian territory should be incorporated to any other state, that the Albanian areas in the three vilayets should form one province, where Albanian officials would control the administration and justice system, and that a national police force would guard the internal stability of this new entity. The "Red Sultan" had initially sought to channel the Albanian national sentiment towards a more religious direction, but having lost control of the events he had dispatched the army to reassert direct Ottoman rule over the Albanian-populated vilayets. The legacy of these actions was still strong in 1900, when events on other side of the world begun to unravel the status quo the Major powers had asserted to the area with the Treaty of Berlin. Back in Ottoman Empire the thirty-two years of despotic rule of Abdülhamid II had created a whole new generation of reformists and revolutionaries, with many notable Albanians among them. As they were meeting one another in exile and secrecy and forming grassroot organizations aimed to topple the rule of the hated Sultan, none of them realized how quick and dramatic changes their homeland would soon experience.

Last edited:

Ah, the eternally interesting, eternally bewildering, eternally terrifying world of the Balkans in the early 1900s.

Or, well, most of the 1900s. And 1800s. And...

Never mind, I'll think of a new comment.

Or, well, most of the 1900s. And 1800s. And...

Never mind, I'll think of a new comment.

Great to see an update after such a long break!

Edit: I find it fascinating how these radical groups popped up just about everywhere around the turn of the century. In China, Albania, the Ottoman Empire in large and more and more in Africa and the remaining West Indies colonies with the Pan-African Congresses as the most obvious example.

Edit: I find it fascinating how these radical groups popped up just about everywhere around the turn of the century. In China, Albania, the Ottoman Empire in large and more and more in Africa and the remaining West Indies colonies with the Pan-African Congresses as the most obvious example.

Last edited:

Chapter 19: In the Court of the Crimson Sultan - Ottoman Empire and the Major Powers at the beginning of 1900s. Part I: Britain

In the Court of the Crimson Sultan - Ottoman Empire and the Major Powers at the beginning of 1900s. Part I: Britain

By 1900 the continued existence of Ottoman Empire was internationally viewed more and more as a geopolitical compromise that the Major Powers had struck between themselves, rather than genuine statehood based on the own inherent strength of this once-glorious realm. And to a large extend this view was quite correct estimation of the situation. Full territorial sovereignty had for long been only an elusive mirage to the Ottoman rulers, and ever since the Paris Conference of 1856 the major powers of Europe had refused all pleas to alter their dominant position in the Ottoman affairs. The Powers had a strong grasp of the Ottoman state both politically and economically, and the previous history of interaction between the Porte and foreign governments showed no indication that this trend could be easily reversed. The story of slow decline of Ottoman power resembled the subjugation of China quite a bit: the unequal treaties had started as agreements that had forced the Ottoman authorities to grant the foreign powers and their subjects rights to supervise the religious rights of non-Muslim subjects of the realm. Later on they had been expanded to include free trade, tariff limits, and so forth. By 1900s the situation was so lopsided that even private citizens of Major Powers within the Ottoman realm had long been protected by the Capitulations - treaties ensuring them privileges and extraterritorial rights and protection by their own government agencies. The sizable expatriate communities living in Ottoman Empire lived isolated lives from the society that surrounded them - the foreigners had their own schools, hospitals, post offices, consular courts and prisons that they used in isolation and immunity of Ottoman administration and laws.

These arrangement had steadily weakened the authority, power and available funding of the Ottoman state on a time when rapid technological progress offered a chance and a strong impetus to modernize and reform the Empire. But obtaining Western technology and support was tricky, and had so far always arrived with strings attached. For example, once the Ottomans had taken their first international loans in 1854 they had soon been caught in a vicious cycle of indebtedness, borrowing more and more to cover the interest payments of former loans, until by 1879 the Empire had been declared to be officially bankrupt. After this the Council of Ottoman Public Debt Administration had been set up by the Powers, and manned largely by foreign creditors it had continued to organize the finances and some of the main revenue-producing areas of the Ottoman economy. To make matters even worse from Ottoman viewpoint, even the Ottoman territorial status quo that the Powers had agreed to jointly uphold had been steadily eroding after the Congress of Berlin in 1878. The following foreign interventions that were officially staged to supervise reform on behalf of the non-Muslim subjects were often nothing more than thinly-veiled imperialist ventures of the Powers themselves.

From a useful pawn to annoying Caliph - decline of the Anglo-Ottoman relations

The British policy towards the Ottoman Empire had gradually changed from the early friendliness of Balta Limani Treaty of 1838 to coldness and occasional hostility presented by Gladstone administration in the five decades that had passed since the end of the Crimean War. No longer was the vast territory controlled by the Ottoman Empire perceived as a crucial strategic buffer against Russian exports to expand southwards. After once supporting them in a major war, making considerable investments and granting generous loans to the Porte, Britain had gradually distanced herself from the Ottoman Empire. Ultimately relations had cooled off so much that Britain had first declared neutrality in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 and then expressed no qualms about dividing Ottoman territory to Balkans states in the following the Treaty of Berlin. By this point British governments had for long advocated that the Ottoman Empire should be reformed from within - but no changes had been forthcoming. After the war British governments had once again publicly stated that henceforth Britain would defend the independence and integrity of Ottoman realms. Claiming this while having already once abandoned Ottomans to their fate in a time of a major war and while simultaneously giving direct and indirect encouragement to the Christian minorities inside the Ottoman Empire and to new Balkan states Seemed more than a bit contradictory to many contemporary observers. Ultimately this double standard in British diplomacy was based on the difference between the Ottoman state and the current Sultan ruling it - Britain was willing to uphold the Empire, but not with the current ruler at the helm.

Both the British public and government officials had by 1900 become convinced that Sultan Abdülhamid II was “the worst ruler Europe had ever known” due the bloody suppression of revolts and dissent in Balkans and Anatolia, and the pan-Islamic foreign policy that the Sultan had used to extend his influence eastwards to British-controlled Muslim territories. Despite her constant misfortunes and subservient position towards the major Powers, the caliphate still retained uncontested political clout as the strongest Muslim power in the world - and for Sultan Abdülhamid II this fact formed the cornerstone of his foreign policy. Rising to power at the dawn of decades when the European powers began a scramble for colonial possessions all across Africa and Asia, the reign of Abdülhamid II had brought the empire string of defeats and constant losses of territory and prestige. With British Empire abandoning the doctrine of preserving Ottoman territorial integrity against the open hostility of Russian Empire, Abdülhamid II had initially appealed to pan-Islamism more of an act of desperation rather than a conscious political choice. By presenting the caliphate to the world as a centralized, universal Muslim institution, Abdülhamid II sought to make himself the representative of the entire Muslim community, and the defender of the religious rights of all Muslims everywhere in the world. This policy had not been without its merits. Whether it was the question of managing the rebellious Muslim communities in Philippines in 1898 or sending diplomatic missions to China to authorize the Caliph in the internal political affairs of Chinese muslims, the Ottoman diplomacy had able to utilize the caliphate to gather them diplomatic influence overseas. And since both France and Germany had been supportive to the Ottoman initiatives in the Far East, the Muslims in China and elsewhere in the region often opted (at least in theory) to recognize the Caliph as their spiritual leader - much to the dismay of British officials who would have preferred their Muslim subjects to swear allegiance to the Crown instead.

Because of the nature of British political system and the strong lobby groups such as the Balkan Committee promoting the cause of Christian minorities in Ottoman Empire in the Parliament, the real political differences between Britain and the Porte could not be treated in isolation of British public opinion. As a result British leaders were obliged to press Macedonian reform on the sultan while being well aware how damaging this was to Britain’s own interests in the realm. Despite the effect of public opinion, ultimately the fundamental fact of British policy towards the Ottoman Empire was its complete subordination to the welfare of the British Empire, and the agreements with other Major Powers. Britain was concerned to prevent any major or sudden disintegration of Ottoman Empire since such a major geopolitical change would be certain to stimulate territorial greed and promote war among the Powers, thus upsetting the British position of strength in the region. The government was thus focused on playing a mediatory role in international crises in the Balkans while trying at the same time preserve the balance of influence among Great Powers and the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire - with or without all its Balkan dominions. Because of this Britain ultimately played a second fiddle in Macedonian reform questions - despite the humanitarian motives of pressure groups in the British society, ultimately British interest to the matter based on the fact that endemic strife in the region was damaging the overall stability of the whole Ottoman Empire.

As the defence of the Straits became less important in British strategy, British officials preferred to maintain the status quo in the matter, unless it were to be altered equally for all the Powers. With no strategic interest for her navy to be able to pass into the Black Sea, Britain had little to gain and much to lose in altering the current situation. Her dominant position in the eastern Mediterranean was a different affair. As the Admiralty memorandum to the Foreign Office pointed out: “A cardinal factor of British policy has naturally been that no strong naval power should be in effective permanent occupation of any territory or harbour East of Malta, if such harbour be capable of transformation into a fortified naval base...Italian occupation [of Aegean islands] would imperil our position in Egypt, would cause us to lose control over our Black sea and Levant trade at its source, and would in war expose our routes to the East via the Suez Canal to the operations of Italy and her allies…” To this end, Britain was was also very anxious to obtain the Porte’s recognition of her exclusive power in the Persian Gulf. As Lord Curzon stated, “the Gulf is part of the maritime frontier of India...It is a foundation principle of British policy that we cannot allow the growth of any rival or predominant political interest in the waters o the Gulf, not because it would affect or local prestige alone, but because it would have influence that would extend for many thousands of miles beyond." British policy in Ottoman Asian territories was thus to contain German ambitions in the region within reasonable limits, while using it to counterbalance traditional Russian southward pressure. For this to happen, British authorities were ultimately willing to relinquish her ambitions in the Bagdad-Gulf line after the Baghdad Railway concession of 1903.

By 1900 the continued existence of Ottoman Empire was internationally viewed more and more as a geopolitical compromise that the Major Powers had struck between themselves, rather than genuine statehood based on the own inherent strength of this once-glorious realm. And to a large extend this view was quite correct estimation of the situation. Full territorial sovereignty had for long been only an elusive mirage to the Ottoman rulers, and ever since the Paris Conference of 1856 the major powers of Europe had refused all pleas to alter their dominant position in the Ottoman affairs. The Powers had a strong grasp of the Ottoman state both politically and economically, and the previous history of interaction between the Porte and foreign governments showed no indication that this trend could be easily reversed. The story of slow decline of Ottoman power resembled the subjugation of China quite a bit: the unequal treaties had started as agreements that had forced the Ottoman authorities to grant the foreign powers and their subjects rights to supervise the religious rights of non-Muslim subjects of the realm. Later on they had been expanded to include free trade, tariff limits, and so forth. By 1900s the situation was so lopsided that even private citizens of Major Powers within the Ottoman realm had long been protected by the Capitulations - treaties ensuring them privileges and extraterritorial rights and protection by their own government agencies. The sizable expatriate communities living in Ottoman Empire lived isolated lives from the society that surrounded them - the foreigners had their own schools, hospitals, post offices, consular courts and prisons that they used in isolation and immunity of Ottoman administration and laws.

These arrangement had steadily weakened the authority, power and available funding of the Ottoman state on a time when rapid technological progress offered a chance and a strong impetus to modernize and reform the Empire. But obtaining Western technology and support was tricky, and had so far always arrived with strings attached. For example, once the Ottomans had taken their first international loans in 1854 they had soon been caught in a vicious cycle of indebtedness, borrowing more and more to cover the interest payments of former loans, until by 1879 the Empire had been declared to be officially bankrupt. After this the Council of Ottoman Public Debt Administration had been set up by the Powers, and manned largely by foreign creditors it had continued to organize the finances and some of the main revenue-producing areas of the Ottoman economy. To make matters even worse from Ottoman viewpoint, even the Ottoman territorial status quo that the Powers had agreed to jointly uphold had been steadily eroding after the Congress of Berlin in 1878. The following foreign interventions that were officially staged to supervise reform on behalf of the non-Muslim subjects were often nothing more than thinly-veiled imperialist ventures of the Powers themselves.

From a useful pawn to annoying Caliph - decline of the Anglo-Ottoman relations

The British policy towards the Ottoman Empire had gradually changed from the early friendliness of Balta Limani Treaty of 1838 to coldness and occasional hostility presented by Gladstone administration in the five decades that had passed since the end of the Crimean War. No longer was the vast territory controlled by the Ottoman Empire perceived as a crucial strategic buffer against Russian exports to expand southwards. After once supporting them in a major war, making considerable investments and granting generous loans to the Porte, Britain had gradually distanced herself from the Ottoman Empire. Ultimately relations had cooled off so much that Britain had first declared neutrality in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 and then expressed no qualms about dividing Ottoman territory to Balkans states in the following the Treaty of Berlin. By this point British governments had for long advocated that the Ottoman Empire should be reformed from within - but no changes had been forthcoming. After the war British governments had once again publicly stated that henceforth Britain would defend the independence and integrity of Ottoman realms. Claiming this while having already once abandoned Ottomans to their fate in a time of a major war and while simultaneously giving direct and indirect encouragement to the Christian minorities inside the Ottoman Empire and to new Balkan states Seemed more than a bit contradictory to many contemporary observers. Ultimately this double standard in British diplomacy was based on the difference between the Ottoman state and the current Sultan ruling it - Britain was willing to uphold the Empire, but not with the current ruler at the helm.

Both the British public and government officials had by 1900 become convinced that Sultan Abdülhamid II was “the worst ruler Europe had ever known” due the bloody suppression of revolts and dissent in Balkans and Anatolia, and the pan-Islamic foreign policy that the Sultan had used to extend his influence eastwards to British-controlled Muslim territories. Despite her constant misfortunes and subservient position towards the major Powers, the caliphate still retained uncontested political clout as the strongest Muslim power in the world - and for Sultan Abdülhamid II this fact formed the cornerstone of his foreign policy. Rising to power at the dawn of decades when the European powers began a scramble for colonial possessions all across Africa and Asia, the reign of Abdülhamid II had brought the empire string of defeats and constant losses of territory and prestige. With British Empire abandoning the doctrine of preserving Ottoman territorial integrity against the open hostility of Russian Empire, Abdülhamid II had initially appealed to pan-Islamism more of an act of desperation rather than a conscious political choice. By presenting the caliphate to the world as a centralized, universal Muslim institution, Abdülhamid II sought to make himself the representative of the entire Muslim community, and the defender of the religious rights of all Muslims everywhere in the world. This policy had not been without its merits. Whether it was the question of managing the rebellious Muslim communities in Philippines in 1898 or sending diplomatic missions to China to authorize the Caliph in the internal political affairs of Chinese muslims, the Ottoman diplomacy had able to utilize the caliphate to gather them diplomatic influence overseas. And since both France and Germany had been supportive to the Ottoman initiatives in the Far East, the Muslims in China and elsewhere in the region often opted (at least in theory) to recognize the Caliph as their spiritual leader - much to the dismay of British officials who would have preferred their Muslim subjects to swear allegiance to the Crown instead.

Because of the nature of British political system and the strong lobby groups such as the Balkan Committee promoting the cause of Christian minorities in Ottoman Empire in the Parliament, the real political differences between Britain and the Porte could not be treated in isolation of British public opinion. As a result British leaders were obliged to press Macedonian reform on the sultan while being well aware how damaging this was to Britain’s own interests in the realm. Despite the effect of public opinion, ultimately the fundamental fact of British policy towards the Ottoman Empire was its complete subordination to the welfare of the British Empire, and the agreements with other Major Powers. Britain was concerned to prevent any major or sudden disintegration of Ottoman Empire since such a major geopolitical change would be certain to stimulate territorial greed and promote war among the Powers, thus upsetting the British position of strength in the region. The government was thus focused on playing a mediatory role in international crises in the Balkans while trying at the same time preserve the balance of influence among Great Powers and the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire - with or without all its Balkan dominions. Because of this Britain ultimately played a second fiddle in Macedonian reform questions - despite the humanitarian motives of pressure groups in the British society, ultimately British interest to the matter based on the fact that endemic strife in the region was damaging the overall stability of the whole Ottoman Empire.

As the defence of the Straits became less important in British strategy, British officials preferred to maintain the status quo in the matter, unless it were to be altered equally for all the Powers. With no strategic interest for her navy to be able to pass into the Black Sea, Britain had little to gain and much to lose in altering the current situation. Her dominant position in the eastern Mediterranean was a different affair. As the Admiralty memorandum to the Foreign Office pointed out: “A cardinal factor of British policy has naturally been that no strong naval power should be in effective permanent occupation of any territory or harbour East of Malta, if such harbour be capable of transformation into a fortified naval base...Italian occupation [of Aegean islands] would imperil our position in Egypt, would cause us to lose control over our Black sea and Levant trade at its source, and would in war expose our routes to the East via the Suez Canal to the operations of Italy and her allies…” To this end, Britain was was also very anxious to obtain the Porte’s recognition of her exclusive power in the Persian Gulf. As Lord Curzon stated, “the Gulf is part of the maritime frontier of India...It is a foundation principle of British policy that we cannot allow the growth of any rival or predominant political interest in the waters o the Gulf, not because it would affect or local prestige alone, but because it would have influence that would extend for many thousands of miles beyond." British policy in Ottoman Asian territories was thus to contain German ambitions in the region within reasonable limits, while using it to counterbalance traditional Russian southward pressure. For this to happen, British authorities were ultimately willing to relinquish her ambitions in the Bagdad-Gulf line after the Baghdad Railway concession of 1903.

Last edited:

Chapter 20: In the Court of the Crimson Sultan - Ottoman Empire and the Major Powers at the beginning of 1900s. Part II: France and Italy.

In the Court of the Crimson Sultan - Ottoman Empire and the Major Powers at the beginning of 1900s. Part II: France and Italy.

Bankers and Missionaries - France

In 1900 France had recently started a campaign of vigorous charm offensives and investment sprees to the Near East, determined to meet the challenge of rising German influence and investments in the Ottoman Empire. In this part of the Franco-German rivalry France started from very advantageous position, as she was a well-established power in Ottoman affairs. Having sponsored Catholic religious orders as protector of the faithful since the sixteenth century, France had long portrayed herself as the defender of Near East Christians, especially the Maronites of Lebanon. In addition to this cultural connection to the 750 000 Catholics in the Asiatic portions of the Ottoman Empire, France had strong economic ties to the Porte. In 1900 French bankers held the most important posts in the administration of the Imperial Ottoman Bank - in fact this financial institution that had utmost importance for the economic life of the Empire had been founded as a joint Franco-British venture in 1863. Since then British investors had lost interest or they had been bought out, and by 1900 the IOB was an operation that was virtually controlled directly from Paris. Financially dominant, France was nevertheless commercially minor player in Ottoman markets. Her market interests in Ottoman territories were mainly focused to Syria, a region French policymakers were inclined to see as an area of exceptional political significance and as a place where France might one day have territorial claims of her own. To this end French government sought to keep Syria as an area where France had the most influence, and where her products dominated the local markets as much as possible. French policy towards Ottoman Empire was largely formulated by the Foreign Minister, and his freedom of action was only occasionally hampered by the parliamentary weakness of the current government. This matter was further emphasized by the fact that policy towards Ottoman Empire was a matter of interest to several political factions in the French Chamber of Deputies. The traditionalist right-wing clerical parties held the traditional French religious protectorate over Middle-Eastern Christians in great value, especially after the events of the Boxer War. The socialist deputies of the extreme Left were also known to promote diplomatic interventions on behalf of Ottoman minorities. But since the influential colonial party was primarily fixated on Morocco and Far East, bankers and industrialists had a strong say in matters involving the Ottoman Empire.

O tutti, o nessuno - Italian policy towards the Ottoman Empire

After unification, Italy had been quick to demand access to the treaties that the Powers had set up in their attempts to steer Ottoman realm towards modernity, and diplomatically Italy was able successfully include herself to Council of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration and join Britain and France in supervising the agreement between Greece and Turkey for the status of Crete. Italian interests in Ottoman territories extended to the Dodecanese, Albania and Adalia, but the unspoken assumption of most Italian diplomats was that strategically and politically it was Vienna, not Constantinople, that was the greater issue to Rome in all geopolitical matters. Even though the Article VII of the Triple Alliance from 1887 between Austria-Hungary and Italy promised undetermined “compensations” for other participants if one of the other gained advantage in the Balkans, Italian diplomats had always privately hoped that they could use this deal to press claims towards Trieste and Trentino in the future. Italy was thus always eager to participate to every international deal or conference regarding Ottoman Empire in the hopes that their country would have something to gain from the results, and was equally opposed to any unilateral changes in the matters of Eastern Question. This "me too"-approach is a partial explanation for Italian interest towards remaining Ottoman territories in North Africa. Having lost her most logical target for colonization, Tunis, to France in 1881 and having been rejected from even planning something similar in Egypt by Britain only a year later, Libya was the only suitable ‘vacant’ Ottoman territory within reach of Italian economical and strategic interests and capabilities. In the first years of 1900s Banco di Roma had already started a considerable investment spree in the region, spurring an increase in Italian commerce. The current vali of Tripoli had little problem with this, as Western investments improved the infrastructure and commercial prospects of his realm, and opposing them might stir up trouble. Diplomatically Italians had also made some groundwork to avoid further humiliations, and when Visconti Venosta and Prinetti-Barrère struck a bargain with France in 1900 and 1902, Italians left with a deal that promised them that whenever 'status quo' would be changed in North Africa, Italy would have a free hand in seizing the Ottoman territories in Libya. But while ambitious Italian businessmen kept telling tall tales of Libyan coast as the destined 'promised land' of Italian people, her political leadership was cautious. Italian Prime Minister Giolitti was however markedly cautious about colonial adventures, having just returned to office for a second time in November 1903. He felt, not unreasonably, that an attack against Libya would equal an attack against whole Ottoman Empire. And such a major war would certainly have unforeseen consequences. “The integrity of what is left of the Ottoman Empire is one of the principles on which is founded the equilibrium and peace of Europe...What if the Balkans move after we have attacked Libya? And what if that Balkan war provokes a clash between the two groups of Powers, and a European war? Italy would be foolish to take on such a terrible responsibility.” For all of their opportunism Italian leaders were anything but reckless, and in the first years of the century they were content to wait and see how the situation in the Balkans would develop before making their own moves to any direction.

"The Enemy of my enemy" - Austria-Hungary

After the decline of Ottoman power, Austro-Hungarian policy towards their old foe had been rapidly changing from hostility to non-hostile neutrality and even occasional cases of indirect support. For Vienna, any power combination replacing the Ottoman Empire would be worse neighbour, whether it would take the form of direct Russian control of Ottoman Balkan territories, or appear as a collection of irredentist South Slavic states looking to Russia for support for their designs on the territories of the Monarchy. “The moment Russia were to establish herself in Constantinople, Austria becomes ungovernable”, the Austrian foreign minister warned Wilhelm II. But in practical political terms Austria-Hungary could do little to uphold her former enemy in the region, since she had only bad and worse options. To use force to resist Greek, Slav or Romanian national movements was never an attractive proposition, whether the aforementioned movements enjoyed Russian support or not. In the first place the large Slav and Romanian populations and relative military weakness of the Dual Monarchy itself would make such interventions extremely risky affairs, and secondly even a successful war would only drive the remaining Balkan states to the arms of Russia. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 the Austrians had therefore resigned themselves to trying to reach an understanding with Russia to limit her influence and to control the Balkans jointly: But when the efforts of Three Emperors Alliance and the Austro-Russian entente of 1897 failed one after another, Austria was running out of options. The public mood in her Serbian client kingdom was deteriorating fast, and the autocratic regime king Alexander I Obrenović had already narrowly avoided a major coup attempt in spring 1903 after the royal marriage of King Alexander I and princess Alexandra zu Schaumburg-Lippe.[1] Insistence to maintain former privileges, such as the Imperial right to protect the Catholics in Albania and Macedonia (the Kulturprotektorat dating back to 1606) were matters where Vienna refused to give any concessions in the fear or damaging their prestige in the region. And this uppity attitude created an insuperable obstacle to the establishment of any kind of really close relations between Vienna and Constantinople. As it was, the final say in the Austro-Hungarian foreign policy lay with the emperor. Although Franz Joseph had no territorial ambitions at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, he had little sympathy for the Ottomans. He loyally supported the joint efforts of the Powers, compelling Abdülhamid II to reform the Macedonian administration. Foreign Minister Goluchowski cultivated Russian entente and was generally equally haughty towards both Ottoman Empire and the Balkan states. Neither the Emperor or his ministers were in any case prepared to fight to maintain the Ottoman Empire.

[1] In January 1900 Đina, the sister of widower Draga Mašin, dies in labour, and Draga has to move away from Belgrade to help the family of her sister. Their short affair with Alexander I withers down as a result, and Alexander I accepts the royal marriage his father has arranged for him. This move does not alienate the Serbian military elite so badly as the OTL scandal, and as a result the assassination and coup attempt orchestrated by Colonel Dimitrijević is exposed and prevented.

Bankers and Missionaries - France

In 1900 France had recently started a campaign of vigorous charm offensives and investment sprees to the Near East, determined to meet the challenge of rising German influence and investments in the Ottoman Empire. In this part of the Franco-German rivalry France started from very advantageous position, as she was a well-established power in Ottoman affairs. Having sponsored Catholic religious orders as protector of the faithful since the sixteenth century, France had long portrayed herself as the defender of Near East Christians, especially the Maronites of Lebanon. In addition to this cultural connection to the 750 000 Catholics in the Asiatic portions of the Ottoman Empire, France had strong economic ties to the Porte. In 1900 French bankers held the most important posts in the administration of the Imperial Ottoman Bank - in fact this financial institution that had utmost importance for the economic life of the Empire had been founded as a joint Franco-British venture in 1863. Since then British investors had lost interest or they had been bought out, and by 1900 the IOB was an operation that was virtually controlled directly from Paris. Financially dominant, France was nevertheless commercially minor player in Ottoman markets. Her market interests in Ottoman territories were mainly focused to Syria, a region French policymakers were inclined to see as an area of exceptional political significance and as a place where France might one day have territorial claims of her own. To this end French government sought to keep Syria as an area where France had the most influence, and where her products dominated the local markets as much as possible. French policy towards Ottoman Empire was largely formulated by the Foreign Minister, and his freedom of action was only occasionally hampered by the parliamentary weakness of the current government. This matter was further emphasized by the fact that policy towards Ottoman Empire was a matter of interest to several political factions in the French Chamber of Deputies. The traditionalist right-wing clerical parties held the traditional French religious protectorate over Middle-Eastern Christians in great value, especially after the events of the Boxer War. The socialist deputies of the extreme Left were also known to promote diplomatic interventions on behalf of Ottoman minorities. But since the influential colonial party was primarily fixated on Morocco and Far East, bankers and industrialists had a strong say in matters involving the Ottoman Empire.

O tutti, o nessuno - Italian policy towards the Ottoman Empire

After unification, Italy had been quick to demand access to the treaties that the Powers had set up in their attempts to steer Ottoman realm towards modernity, and diplomatically Italy was able successfully include herself to Council of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration and join Britain and France in supervising the agreement between Greece and Turkey for the status of Crete. Italian interests in Ottoman territories extended to the Dodecanese, Albania and Adalia, but the unspoken assumption of most Italian diplomats was that strategically and politically it was Vienna, not Constantinople, that was the greater issue to Rome in all geopolitical matters. Even though the Article VII of the Triple Alliance from 1887 between Austria-Hungary and Italy promised undetermined “compensations” for other participants if one of the other gained advantage in the Balkans, Italian diplomats had always privately hoped that they could use this deal to press claims towards Trieste and Trentino in the future. Italy was thus always eager to participate to every international deal or conference regarding Ottoman Empire in the hopes that their country would have something to gain from the results, and was equally opposed to any unilateral changes in the matters of Eastern Question. This "me too"-approach is a partial explanation for Italian interest towards remaining Ottoman territories in North Africa. Having lost her most logical target for colonization, Tunis, to France in 1881 and having been rejected from even planning something similar in Egypt by Britain only a year later, Libya was the only suitable ‘vacant’ Ottoman territory within reach of Italian economical and strategic interests and capabilities. In the first years of 1900s Banco di Roma had already started a considerable investment spree in the region, spurring an increase in Italian commerce. The current vali of Tripoli had little problem with this, as Western investments improved the infrastructure and commercial prospects of his realm, and opposing them might stir up trouble. Diplomatically Italians had also made some groundwork to avoid further humiliations, and when Visconti Venosta and Prinetti-Barrère struck a bargain with France in 1900 and 1902, Italians left with a deal that promised them that whenever 'status quo' would be changed in North Africa, Italy would have a free hand in seizing the Ottoman territories in Libya. But while ambitious Italian businessmen kept telling tall tales of Libyan coast as the destined 'promised land' of Italian people, her political leadership was cautious. Italian Prime Minister Giolitti was however markedly cautious about colonial adventures, having just returned to office for a second time in November 1903. He felt, not unreasonably, that an attack against Libya would equal an attack against whole Ottoman Empire. And such a major war would certainly have unforeseen consequences. “The integrity of what is left of the Ottoman Empire is one of the principles on which is founded the equilibrium and peace of Europe...What if the Balkans move after we have attacked Libya? And what if that Balkan war provokes a clash between the two groups of Powers, and a European war? Italy would be foolish to take on such a terrible responsibility.” For all of their opportunism Italian leaders were anything but reckless, and in the first years of the century they were content to wait and see how the situation in the Balkans would develop before making their own moves to any direction.

"The Enemy of my enemy" - Austria-Hungary

After the decline of Ottoman power, Austro-Hungarian policy towards their old foe had been rapidly changing from hostility to non-hostile neutrality and even occasional cases of indirect support. For Vienna, any power combination replacing the Ottoman Empire would be worse neighbour, whether it would take the form of direct Russian control of Ottoman Balkan territories, or appear as a collection of irredentist South Slavic states looking to Russia for support for their designs on the territories of the Monarchy. “The moment Russia were to establish herself in Constantinople, Austria becomes ungovernable”, the Austrian foreign minister warned Wilhelm II. But in practical political terms Austria-Hungary could do little to uphold her former enemy in the region, since she had only bad and worse options. To use force to resist Greek, Slav or Romanian national movements was never an attractive proposition, whether the aforementioned movements enjoyed Russian support or not. In the first place the large Slav and Romanian populations and relative military weakness of the Dual Monarchy itself would make such interventions extremely risky affairs, and secondly even a successful war would only drive the remaining Balkan states to the arms of Russia. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 the Austrians had therefore resigned themselves to trying to reach an understanding with Russia to limit her influence and to control the Balkans jointly: But when the efforts of Three Emperors Alliance and the Austro-Russian entente of 1897 failed one after another, Austria was running out of options. The public mood in her Serbian client kingdom was deteriorating fast, and the autocratic regime king Alexander I Obrenović had already narrowly avoided a major coup attempt in spring 1903 after the royal marriage of King Alexander I and princess Alexandra zu Schaumburg-Lippe.[1] Insistence to maintain former privileges, such as the Imperial right to protect the Catholics in Albania and Macedonia (the Kulturprotektorat dating back to 1606) were matters where Vienna refused to give any concessions in the fear or damaging their prestige in the region. And this uppity attitude created an insuperable obstacle to the establishment of any kind of really close relations between Vienna and Constantinople. As it was, the final say in the Austro-Hungarian foreign policy lay with the emperor. Although Franz Joseph had no territorial ambitions at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, he had little sympathy for the Ottomans. He loyally supported the joint efforts of the Powers, compelling Abdülhamid II to reform the Macedonian administration. Foreign Minister Goluchowski cultivated Russian entente and was generally equally haughty towards both Ottoman Empire and the Balkan states. Neither the Emperor or his ministers were in any case prepared to fight to maintain the Ottoman Empire.

[1] In January 1900 Đina, the sister of widower Draga Mašin, dies in labour, and Draga has to move away from Belgrade to help the family of her sister. Their short affair with Alexander I withers down as a result, and Alexander I accepts the royal marriage his father has arranged for him. This move does not alienate the Serbian military elite so badly as the OTL scandal, and as a result the assassination and coup attempt orchestrated by Colonel Dimitrijević is exposed and prevented.

Last edited:

Chapter 21: In the Court of the Crimson Sultan - Ottoman Empire and the Major Powers at the beginning of 1900s. Part III: Russian Empire.

In the Court of the Crimson Sultan - Ottoman Empire

and the Major Powers at the beginning of 1900s. Part III: Russian Empire.