You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."The tragicomic aspect of this is that so far everything mentioned above has been more or less 100% historical. All of the above-mentioned British weapons and their place in the British artillery park are so far completely historical, as well as their design, since the starting situation is more or less exactly the same as in OTL. The key differences will come along as the situation deviates from OTL.^^^^ I can imagine this may lead to some significant differences in operational use in any near term continental fights between the major powers

And in the case of the Norwegian Secession War, things are different but similar enough:

The Japanese had telephone cables from the start, and the Russians quickly followed suit after they had lost a lot of batteries deployed for direct fire. Whereas the Swedes and Norwegians were pioneers of field telephone systems, but the Norwegian artillery had initial doctrinal focus on direct fire.

Both the Japanese and Russians made exactly similar adaptations in OTL than the Swedes and Norwegians in TTL, and they were reported to European powers from Manchuria well enough to get the message accross to those willing to listen. The quote about the uselessness of flat-trajectory artillery weapons in hilly terrain is from Manchuria, for example.

And just like in OTL, one can observe exactly the same situation and draw completely opposite conclusions.

Chapter 246: The Royal Artillery, Part VII: Continental comparisons

Continental armies had little doubt of their future battlefields and future adversaries, and they could and did plan accordingly.

The French army was a force built from the ground up with the sole aim of avoiding the defeat of 1870. As it had been so often before, the French had led the way in military innovation in Europe in their quest to reform their artillery.

They had basically created the entire consept of a quick-firing field artillery with their revolutionary 1897 soixante-quinze quick-fire gun, a 75mm weapon that predated South Africa and Norway. The automatic fuse-setting machine, exceptionally stable firing platform and recoil-absorbing system that eliminated the need to run the gun back into position were features that allowed the new gun to reach unprecedented rates of fire.

By 1900 the entire French field artillery was more or less built around their 75mm QF guns.

The conclusion from Norway was clear for the French strategists: their approach had been validated. Slow and methodical approach had only lead to grinding and inconclusive battles of attrition, whereas the Swedes had gained most ground during their initial advance, where they had essentially maneuveured to bypass the heaviest Norwegian defences and had been able to again and again turn the flank of Norwegian defensive positions.

When artillery was used, it was the first, surprising round that killed the enemy and temporarily paralyzed his will to resist.

As a result the French maintained their practice where their artillery used a bare minimum of ranging rounds before firing for effect. The preferred tactic was to focus on surprise and suppressive shock effect of a quick, annihilating rafale of intense artillery fire, that would be immediately followed by a determined infantry assault.

However, the way the Norwegian fixed fortifications at Kongsvinger had managed to stop the equally offensive-minded Swedes troubled some French decision-makers. The need for heavy artillery to deal with the forts that would otherwise tie down significant forces for cordoning and siege duties was a tactical dilemma the French could not solve immediately without altering their doctrine accordingly, but the appearance of British 60-pounders and reports from South Africa increased pressure to discuss the potential impact of a situation where an enemy would have the freedom to harass French forces that were still deploying for an attack in a meeting engagement with their own heavier artillery pieces and fixed fortress artillery.[1]

The British critics of the French doctrinal approach stated that such ammunition use was both extravagant and uneconomical. However, the French tactical approach was appealing for British infantry officers, who were quick to point out that while the gradual and accurate method of British gunners was "too scientific and slow", and that while the gunners were still calculating the attacking British infantry would either lose the initiative while waiting fo the artillery, or fall to victim of rapidly deployed and aggressively used enemy artillery.

Meanwhile the Germans, facing rings of French, Russian and Belgian field fortifications all around their borders and potential future battlefields, had to plan accordingly.

Not inclined to sacrifice firepower for maneuverability, the post-1905 German instructions preferred concealed positions and indirect fire. Divisional artillery commanders retained control of their artillery as long as possible to enable correct tactical utilization of the guns. Map shooting, meteoric conditions, command observation post vehicles, communications and coordination of reserve artillery regiments with the divisional artillery were all part of the German doctrine for the era of quick-firing artillery.

The presence of fortresses and field fortifications was a key dilemma for German General Staff planners. To solve it, they increased the numbers of howitzers in their infantry divisions to eighteen (18) 105mm howitzers per division, twelve (12) 150mm howitzers per corps, and formed a special reserve of army-level 210mm howitzer units. The future German artillery would be a heavy-hitter, but it would also be a force primarily designed for the dense railroad networks and good roads of central Europe.[2]

1: This is a type of tactical situation that did not occur in OTL, as the siege of Port Arthur was more of a traditional siege rather than part of a wider field battle like the Kongsvinger in TTL.

2: All OTL. Both TTL and OTL German planners choose to downplay the fact that these changes increased the supply demands of their divisions accordingly.

The French army was a force built from the ground up with the sole aim of avoiding the defeat of 1870. As it had been so often before, the French had led the way in military innovation in Europe in their quest to reform their artillery.

They had basically created the entire consept of a quick-firing field artillery with their revolutionary 1897 soixante-quinze quick-fire gun, a 75mm weapon that predated South Africa and Norway. The automatic fuse-setting machine, exceptionally stable firing platform and recoil-absorbing system that eliminated the need to run the gun back into position were features that allowed the new gun to reach unprecedented rates of fire.

By 1900 the entire French field artillery was more or less built around their 75mm QF guns.

The conclusion from Norway was clear for the French strategists: their approach had been validated. Slow and methodical approach had only lead to grinding and inconclusive battles of attrition, whereas the Swedes had gained most ground during their initial advance, where they had essentially maneuveured to bypass the heaviest Norwegian defences and had been able to again and again turn the flank of Norwegian defensive positions.

When artillery was used, it was the first, surprising round that killed the enemy and temporarily paralyzed his will to resist.

As a result the French maintained their practice where their artillery used a bare minimum of ranging rounds before firing for effect. The preferred tactic was to focus on surprise and suppressive shock effect of a quick, annihilating rafale of intense artillery fire, that would be immediately followed by a determined infantry assault.

However, the way the Norwegian fixed fortifications at Kongsvinger had managed to stop the equally offensive-minded Swedes troubled some French decision-makers. The need for heavy artillery to deal with the forts that would otherwise tie down significant forces for cordoning and siege duties was a tactical dilemma the French could not solve immediately without altering their doctrine accordingly, but the appearance of British 60-pounders and reports from South Africa increased pressure to discuss the potential impact of a situation where an enemy would have the freedom to harass French forces that were still deploying for an attack in a meeting engagement with their own heavier artillery pieces and fixed fortress artillery.[1]

The British critics of the French doctrinal approach stated that such ammunition use was both extravagant and uneconomical. However, the French tactical approach was appealing for British infantry officers, who were quick to point out that while the gradual and accurate method of British gunners was "too scientific and slow", and that while the gunners were still calculating the attacking British infantry would either lose the initiative while waiting fo the artillery, or fall to victim of rapidly deployed and aggressively used enemy artillery.

Meanwhile the Germans, facing rings of French, Russian and Belgian field fortifications all around their borders and potential future battlefields, had to plan accordingly.

Not inclined to sacrifice firepower for maneuverability, the post-1905 German instructions preferred concealed positions and indirect fire. Divisional artillery commanders retained control of their artillery as long as possible to enable correct tactical utilization of the guns. Map shooting, meteoric conditions, command observation post vehicles, communications and coordination of reserve artillery regiments with the divisional artillery were all part of the German doctrine for the era of quick-firing artillery.

The presence of fortresses and field fortifications was a key dilemma for German General Staff planners. To solve it, they increased the numbers of howitzers in their infantry divisions to eighteen (18) 105mm howitzers per division, twelve (12) 150mm howitzers per corps, and formed a special reserve of army-level 210mm howitzer units. The future German artillery would be a heavy-hitter, but it would also be a force primarily designed for the dense railroad networks and good roads of central Europe.[2]

1: This is a type of tactical situation that did not occur in OTL, as the siege of Port Arthur was more of a traditional siege rather than part of a wider field battle like the Kongsvinger in TTL.

2: All OTL. Both TTL and OTL German planners choose to downplay the fact that these changes increased the supply demands of their divisions accordingly.

^^^ Who has shifted their doctrinal approach the most from OTL? Or, is on a path to shift even more as non-combat field lessons are learned?

So far the single biggest deviation is the undisturbed reform of the Russian Army under Kuropatkin: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...-century-history.272417/page-16#post-12061143

Chapter 247: The Royal Artillery, Part VIII: "'Whatever happens, we have got..."

By the Boer War, a machine gun was nothing new or out of the ordinary in the modern battlefield.

The various Gardners, Gatlings and Nordenfelts had been in British service for nearly 20 years, but they had all been plagued with problems inherent to their technical designs. They were prone to jam, and had a relatively slow rate of fire.

Enter Hiram Maxim.

A man who had seemed poised to serve humanity by focusing on his notable talents as an electrical engineer (Maxim invented the first practical incandescent light bulb and efficient current regulator) had been essentially bought out of the market by the financial backers of Edison.

They had made Maxim a lucrative offer: he would be hired as a “technical advisor” for them in Europe - but he would have to cease all work in the field of electricity innovation for a decade.

Now financially independent and out of electrical engineering business, Hiram had settled in London.

He later on recalled how during his youth he had fired a new Springfield rifle just after the Civil War, and had had the idea of using a belt of cartridges and the energy created by the recoil.

He and his father had estimated that the technology of the day would not be sufficient to produce such a new weapon in an economic way. That was then. Now times were different, and Maxim had the money and leisure time to revisit his idea.

Despite being able to patent his new locked-breech recoil system and recoil-operated Winchester-type rifle, his ideas also offered concepts for other weapon designers, such as Ferdinand Ritter von Mannlicher.

As his company and fame grew, Maxim joined forces with Albert Vickers, a joint owner of the Vickers, Son & Company Ltd. The two inventors also found an important patron from Sir Garnet Wolseley, who was perhaps the most famous of British late Victorian-era generals.

By the Chitral expedition of 1895, six .303 Maxims had just reached India mere two months before the operation. Three had been issued with the troops, with a practically unlimited supply of ammunition due the shared caliber with the Lee-Metford and Lee-Enfields.

Used against the ghazis rushing against the British lines in the Malakand Pass and to clear sangars on the hillsides, the experience with Maxims in mountain warfare quickly settled the question of their general adoption in the British army.[1]

The Battle of Omdurman on 2nd of September 1898 had cemented the legend of the Maxim. Wrapped in a special silk to cover the guns against the sand and dust, the Maxims were used against the Sudanese jihadists with murderous effectiveness.

After their new fame as a wonder weapon, the machine guns were more or less bound to perform below expectations in South Africa, despite the fact that the British Army had stripped every possible fortress piece along to get as many machine guns to the area as possible.

Deployed into the open in the manner of Sudan, the Maxims were silenced by Boer Mauser fire just like the rest of the British artillery pieces.

After the war, both the tactical role of machine guns and their place in the British order of battle received new attention, alongside with the perceived need to technically develop the weapon type further alongside with the general reform of the rest of the British artillery arm.

1. They also converted Bindon Blood into avid supporter of machine guns, both TTL and OTL.

Last edited:

Driftless

Donor

Deployed into the open in the manner of Sudan, the Maxims were silenced by Boer Mauser fire just like the rest of the British artillery pieces.

After the war, both the tactical role of machine guns and their place in the British order of battle received new attention

How does this situation compare to OTL?

largely as per otlHow does this situation compare to OTL?

Driftless

Donor

How does this situation compare to OTL?

largely as per otl

I always think one of the really nifty aspects of this TL is how close it can stick to historic events, but a few sometimes subtle changes could have had bigger impacts than we often think. Basically, the plausibility factor is very high here.

*edit* Also, my depth of knowledge of many of these events is limited, (i.e. the 100,000 meter overview level....)

Last edited:

Chapter 248: The Royal Artillery, Part IX: Cooperation and Competition

The artillery reform was considerably expensive.

As the new Liberal government that took office was committed to reducing the cost of the army whenever possible, large-scale rearmament programs met political realities. With the machine gun viewed as a "weapon of opportunity", what was initially allowed and encouraged was further testing.

And as always, test lured in a lot of private companies both from home and abroad.

Different types of collaboration between competing weapon companies was rather common at the turn of the century. From armored plates of warships to high-carbon steel strategic materials, refined components and most importantly patents and information crossed borders rather often to boost revenues on both sides.

Krupp, a company that had managed to gain a high standing at the German court and politics, was a prime example of this type business mindset: their salesmen were perfectly willing to ignore the political tensions between the Great Powers when there was profit to be made.

Nearly 50% of Krupp sales came from foreign sales, and over 50 different nations were in their list of customers, including substantial orders from Russia. They also had a lot of business in Britain.

In 1895 a new improved Krupp time fuse for artillery ammunition was internationally patented so that a fee would have to be paid for each produced example.

A year later Krupp and Vickers had struck “a shilling a shell”-deal. Krupp had provided detailed specs, while Vickers had agreed to pay 1s 3d [0,06£] per each fuse fitted to a shell. To maintain the corporate brand the deal had also obligated Vickers to stamp a KPz (Krupp Patentzünder) symbol on each shell.[1]

These types of deals were not one-sided, and Krupp was not the only German company dealing with British firms.

Ludwig Loewe and his company had secured a seven-year licence from Maxim in 1892, and had managed to sell the license-built weapon to the Kriegsmarine in 1894, followed by a deal to produce an improved Maxim Model 1901 machine gun for the Germany Army.

After Loewe's company had become a part of the new Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken, Vickers had established a joint small arms production business with DWM. The German company’s approval was required for joint sales of guns in Germany and in a specified set of other countries, with profits equally divided between the two companies.

After the seven year-long “leash agreement” between DWM and Vickers had expired in 1898, the Germans had quickly turned into a serious competitor in international markets for machine guns, while their factories still used components produced by Erith Works and Crayford Works in Kent.[2]

As they sought to secure a new deal from the British government, the engineers of Vickers inspected the localized production version that their business partners/competitors at DWM had made to the original Maxim design.

They concluded that the German modifications were a curious mix of practical and puzzling design choices. The DWM had sensibly reduced the overall weight, and eliminated the heavy tripod - only to replace it with an equally clumsy and heavy Schlitten 08 sledge mount. They had also ignored the improved 1901 lock and kept the old non-adjustable 1889 design that only trained armourers could headspace. [3]

The German version also had a muzzle booster that raised the rate of fire to 450rpm while also improving cold-weather performance. It also had a side mount for an optional telescopic sight.

The general conclusion at Vickers was far from happy: as it was, the British design was slightly more expensive than the German variant, and had little features that made it stand apart as a preferable choice.

Alarmed by the possibility of being bested out of a crucial deal by a reverse-engineered version of their own gun and inspired by some of the design choices the Germans had made, Vickers engineers Buckham and Dawson literally turned the entire mechanism upside down.

Their efforts paid off: the extensively re-designed and improved 1908 Light Pattern Vickers was an immediate commercial success.

In 1910 it was on trials at Hythe against the German DMW 1901 commercial models.

A long, complex report from the School of Musketry, after tens of thousands of fired rounds and tests with mud- and sand-covered belts, was conclusive in recommending the Vickers.

The new British machine gun was lighter, had various advantages in mechanical details, and had a great superiority in ease of stripping and exchanging broken and damaged components. The new “Mount, Tripod Mark IV” was also a success: it provided an unlimited arch of fire in a package that was both robust, easy to assemble and light enough to be carried by one man.

The tests were enough to convince the Army to procure the new machine gun for the Cavalry divisions[4], but the remaining funds were already being focused on another pressing topic in the British military reform: rifles.

1-4: All OTL!

Chapter 249: The Rifle Question, Part I: A Most Detailed Devil

Engineers, chemists, sportsman shooters, expert marksmen, infantrymen and cavalrymen. Historians, military theorists, generals - and the common soldier.

Not to mention the self-proclaimed experts at the press and the man on the street. Everyone had an opinion when it came to the topic of modern military rifles.

It all started from the measurements. Every ounce of weight had to be taken into consideration, for weight saved in the arm could be added to the ammunition and other equipment carried.

At the same time the rifle had to be obviously strong enough to stand rough usage and strain of bayonet fighting. The older rifles had been longer partially to make them better for bayonet work, but also to enable for rank firing in close order.

Bolt actions had become universal, but aside from that several features separated the similar-ish rifles of the armies of the world from one another. A straight pull action, such as in the Austrian or Swiss rifles, or a turning bolt?

A box magazine - a narrow or deep one, with a single or double row of cartridges? And with a cut-off or maybe even a horizontal Krag-Jorgensen type box with a trapdoor in the side of the rifle?

A charger system or a clip magazine? How many cartridges per clip?

A box magazine, bolt action and the placement of the breech action all curtailed the size of the barrel. The barrel had an important bearing on the velocity.

And the cartridges, oh! Rimmed cartridges took up more room in packing than rimless ones. They were also more liable to jam.

Rimless cartridges had nothing more than the taper at the neck and the extractor hook preventing them being accidentally forced too far forward into the chamber.

And their propellant! The legendary cordite had survived much criticism. It imparted high velocity for bullets fired from shorter barrels than before in a way that had been impossible with black powder.

It had many merits: it was stable, efficient, very controllable and trustworthy in all climates of the British Empire.

Excessive barrel erosion, its chief drawback, was lately being greatly diminished with modified mixture containing only 30% of nitroglycerin instead of the old 58%.

With the propellant debate more or less settled, there was the question of bullet velocity: the designers were after the "impossible ideal" of a bullet travelling for 3 000 yards in a straight line and then dropping to the ground.

Penetration and force of blow of the bullet were of course important as well. But the experts agreed that the main difficulty for efficient musketry in a modern war was that of adjusting the aim to the distance of the mark.

As long as range finding remained little more than a matter of guesswork, the importance of a flat trajectory was enormous, for it diminished the necessity of accurate guessing.

But higher velocity could only achieved by larger flow of gases under increased pressure. As charges in the cartridge grew, pressures were increased in turn.

This could only be avoided by an equal increase in the capacity of the cartridge to achieve a reduced gravimetric density.

If the pressures were to be kept within reasonable limits, the cartridge had to be enlarged to an awkward shape, while the barrel necessarily suffered more from the action of the gases and the bullet upon it.

The caliber was really the crux of the matter.

Chapter 250: The Rifle Question, Part II: The 6½-mm Goes to War

The change which had taken place in military arms c. 20 years ago had been a success because of practicable smokeless propellants. As the reduction of the calibre reduced the size and weight of the ammunition, it enabled the soldier to carry a much increased number of rounds, and made the box magazine a practicable feature in modern rifles.

The rapidity and certainty of fire from weapons capable of firing bullets travelling 2 miles with great accuracy, and with such velocities that they would penetrate a foot of timber at 1 000 yards had been a military revolution that had defined every military conflict ever since.

The .300 to .315 inch (7½ to 8 mm) calibre had been the choice of most foreign Powers. By 1900 opinion of nations seemed to be divided as to the advantages of further reduction of calibre. Italian .256 (6½-mm) Mannlicher-type had been in service for 14 years. Romania (1893), Holland (1895) and the Japanese (1900) had followed suit.

Spain used an intermediate calibre, the .276 (7mm), similar to the arm of the Boers. The US Navy had boldly adopted the very small calibre of .236 (6mm), but had abandoned it shortly afterwards, altering the form of their cartridge to get a higher velocity, while retaining the .300 calibre.

Germany had modified the pattern of the Mauser rifle without changing the cartridge, and the Swiss had followed suit in 1900 by modifying their rifle but maintaining their calibre.

Many military experts felt that undue reduction of the calibre would mean a loss of wounding power at very long ranges, while also increasing deflection of the bullet by the wind.

Then war came to Scandinavia.

The Norwegian Krag-Jorgensens and Swedish Mausers both fired .256-caliber (6½-mm) ammunition. The caliber gave a velocity of 2,400 f.s. without immoderate pressures, with a well proportioned bullet, and no significant deficiencies in wounding power.

It had indeed been "an admirable choice" for soft-skinned game hunting among British officers in India well before.

Though it provided less of a blow at extreme ranges, the higher velocity gave it an advantage in penetration and in flatness of trajectory - both very important matters.

Even before the war the smaller caliber had compared favorably to .315-inch ammunition in tests conducted in Norway by having a flatter trajectory, greater accuracy, especially at the shorter distances.

Drift and influence of the wind had been practically identical for both calibers, but the smaller .256 penetrated further in wood and as far in earth as the larger, while remaining less deformed.

The .256 ammunition had one extra definite advantage over the .315: a 15% lesser weight - 22% less than the new U.S. cartridge of .300 bore (which gave the same velocity), while the .256 was decidedly less bulky when compared to either.[1]

Opponents of smaller calibres were quick to point out that after firing hundreds of bullets in battles lasting for several days in a row, the barrels of the Norwegian and Swedish service weapons must have had gone through extreme wear and following loss of accuracy.

The proponents of the .256 granted that the chief point of doubt about the calibre the increased wear and erosion, and granted that cordite as it was used in the British rifles with the original mixture was indeed perhaps too erosive a propellant for a .256 rifle; but the countered that by pointing out that ballistite, such as used by the Italians, had much the same character and could offer an alternative.[2]

The Norwegian Secession War offered an interesting angle to the debate about the current status and future design choices of the British service rifle.

1: All quotes are from lecture called "Modern Military Rifles" held by Major T. F. Fremantle 1st Bucks Volunteer Rifle Corps at the Royal United Service Institution on Tuesday 28th March, 1905.

The Swedish 6.5×55mm really was the topic of the aforementioned comparisons and favorable quotes, while it also plays the role of OTL 6.5x50 mm Arisaka as a smaller calibre used in a modern war.

2. Just like they pointed out the alleged condition of Japanese and Russian barrels during the Russo-Japanese War in OTL.

Major Fremantle is just a technical expert and likes the calibre personally, as many other British shooters and hunters do. The people actually calling the shots have other ideas, even though they are taking the latest events into account - in their own way.So we're getting a rimmed .256 British? ye god. Too bad spitzers are not quite there yet for the UK. (norway and sweden both used roundnoses in the war)

Yeah the Spitzer sorta killed the 6.5 caliber as a whole as a serious contender for further military adoption so they'll probably do as per OTL and adopt a spitzer .303 in 1910.Major Fremantle is just a technical expert and likes the calibre personally, as many other British shooters and hunters do. The people actually calling the shots have other ideas, even though they are taking the latest events into account - in their own way.

Chapter 251: The Rifle Question, Part III: Old Smelly

The evolution of the current British service rifle had started with an upgrade to the .303-inch ammunition. In 1892 the old black-powder-load had been replaced by new smokeless cordite - a new mixture of nitro-glycerine, gun cotton and mineral jelly.

The “Emily” MLE firing this new ammunition was born from the inventions of two inventors: William Metford and James Paris Lee. Metford had been an advocate of smaller calibres for his entire life, and had created a new barrel rifling system to overcome problems associated with black powder fouling.

Lee, in turn, had developed a new ingenious bolt-action, magazine-fed mechanism.

The new rifle combining these two inventions had been plagued with problems from the start. The higher temperature of the new propellant that had produced little to no fouling in the test trials soon started to have an unforeseen degrading effect on the shallow groove rifling of the Metford barrels, turning them dangerously unreliable after c. 6000 rounds.

Cordite had also increased the bullet velocity from 1,850 fps to 1,970 fps. The Mk VI cartridge with the old round-nosed 215 grain bullet was simply unable to cope with this increase, and became too unstable at extended ranges.

To remedy the fouling, the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield had designed a new rifling, using five grooves with a left hand-twist. A committee program to improve the ballistics of the bullet was also launched.

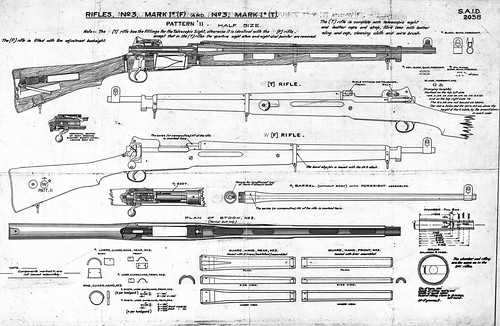

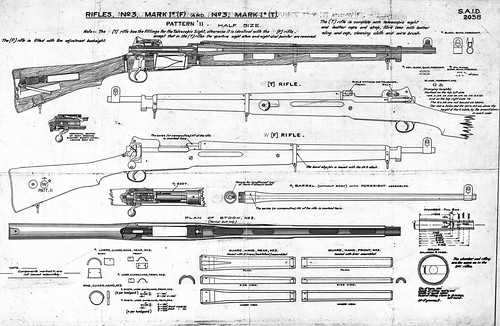

The old Lee-Metford, now upgraded with the Enfield rifling, had been adopted for service in 1895 as the .303 calibre, Rifle, Magazine, Lee-Enfield.

It had seen service in Sudan, Nigeria, North West Frontier and South Africa.

The “Long Lee” also saw service during the Boer War, but it still wasn’t a universal British rifle.

The forces in South Africa fought the war with a variety of different service rifles, including older Lee-Metfords, as well as cavalry and artillery carbine versions of both Lee-Metfords and Lee-Enfields.

As the carbines proved themselves unsatisfactory weapons, the desire to save money led to the decision to arm both infantry and cavalry with the same rifle.

This led to adoption of the “Smelly” - SMLE, Short Magazine Lee-Enfield.

It featured a Mauser-type charger loading system. The war experience showed: the new rifle was lighter, easier to handle, and had better sights and a charger-fed magazine system to improve reloading. It also utilized draw pull, which had already been universally in use in Continental rifles. Safe margin of weight combined with comparatively delicate release further increased the accuracy of the weapon.

The new rifle was also shorter, as the name implied: the Snider, the first breech-loading rifle in British military service, had a length of 4 feet 7 inches. The Martini-Henry was 5 and half inches shorter. The new Short Lee-Enfield measured 3 feet 8 inches without the bayonet.

A further update, the SMLE Mk III, introduced on 26 January 1907, had a simplified rear sight arrangement and a fixed charger guide, improved handguard and magazine, and it was built to fire the new Mk VII High Velocity spitzer .303 ammunition that was still in development.

Following the example of the French 1898 Lebel “boat-tail” bullet, the British had changed the shape of their bullets to improve their aerodynamics. The new ammunition had a lighter 174 grain spitzer bullet.

The new rifle and ammunition received criticism. While a .303 rifle with a well-made barrel and properly designed bullet was deemed capable of making quite as accurate shooting as the best of the Continental rifles, with ordinary service ammunition the SMLE was deemed less accurate than rifles like the Dutch pattern .256 Mannlicher and the Mexican pattern .276 Mauser.

Both the ammunition and the rifle were mocked as obsolete, for only Portugal, Denmark and Britain now had service rifles with working pressures under 16 tons. The "measly" 15¼ tons for the Lee-Enfield and 15¾ tons for the short L.E. made the British small arms look weak in comparisons. The Ottomans, Austria and Belgium used rifles with working pressures of 19½, while Germany had 21![1]

The new short rifle of the US Army was designed to have a normal pressure of 20, with the action successfully tested with cartridges loaded to give 29 tons.

The defenders of the upgrade replied by stating that the ability to penetrate 9 inches of bricks, or 14 inches of mortar, or 18 inches of packed earth at 100 yards showed that the new Enfield ball ammunition was not short of power.

But for the critics of the rifle and ammo, the speed of the bullet was still too low for their liking. They were quick to point out that a combination of entirely another rifle and ammunition was currently dominating the long-range target shoot competitions such as Bisley and Camp Perry.

1: All OTL. Pre-war, many regarded the SMLE as an obsolete ad-hoc interim update that would have to be replaced with a truly modern military rifle as soon as practically possible.

Last edited:

IIRC in terms of construction the SMLE was obsolete, far too many parts and too much machining required. Like you say in the footnote they wanted a more modern rifle which would become the P13. Which I assume will be different ITTL, in calibre at least (it might actually get adopted this time!)

Chapter 252: The Rifle Question, Part IV:"in the interest of defence and the permanence of the volunteer and auxiliary forces"

Even after Lord Roberts and his Indians had joined forces with the Cavalry faction of the British officer corps to adopt the new short Lee-Enfield, the rifle question was far from finally settled.

There remained a number of constituencies within the Army who were unconvinced about the SMLE and in particular were concerned by the ability of the weapon to stop an enemy dead. The SMLE allowed the various branches of the Army to continue to think about the battlefield and tactics in ways that suited them - but for some of them, the Army needed an entirely new weapon, and quickly.

Made up of members of the NRA and doubting politicians such as Hugh Arnold Forster, the Secretary of State for War from 1903 until 1905, these actors questioned the need for a short-barrelled rifle and were concerned by the Army's decision to abandon the Lee-Metford.

The NRA had been established in November 1859. Formed by members of the Volunteer Force, the ambition of the new association was to improve not only the shooting skills of the Volunteers but also of rifle shooters generally. By holding regular competitions the hope was to make shooting as popular as other British sporting events. With the Prince Consort as Patron and the Duke of Cambridge offering an annual prize, the NRA had very close links with Royalty and the British military establishment.

The appointment of Lord Roberts to the position of Vice-President of the Association in 1901 and the eventual death of the Duke of Cambridge in 1904, had kept the NRA quiet when the SMLE had been adopted. Despite its official position of neutrality in the issue, individual members tended to have very particular views about rifles, and they brought them up in a number of newspapers and journals. Wedded to hitting conventional bull's eye targets at set distances, the association encouraged a view of marksmanship that was invariably at odds with the new demands of the battlefields of South-West Frontier and South Africa.

As far as the NRA's membership was concerned, the key ability of a good service rifle was the capability of accurately striking targets out to long range distances. Accordingly, members took a dim view of the SMLE because it did not fit with their ideas on marksmanship and rifle design. In particular they were not happy with the shortness of the rifle, the lack of a wind gauge for the rear sight and the suitability of cordite ammunition for target shooting.

By 1908 they had found their new favourite, and influential political forces were soon once again at work to influence the procurement decisions of the British military.

There remained a number of constituencies within the Army who were unconvinced about the SMLE and in particular were concerned by the ability of the weapon to stop an enemy dead. The SMLE allowed the various branches of the Army to continue to think about the battlefield and tactics in ways that suited them - but for some of them, the Army needed an entirely new weapon, and quickly.

Made up of members of the NRA and doubting politicians such as Hugh Arnold Forster, the Secretary of State for War from 1903 until 1905, these actors questioned the need for a short-barrelled rifle and were concerned by the Army's decision to abandon the Lee-Metford.

The NRA had been established in November 1859. Formed by members of the Volunteer Force, the ambition of the new association was to improve not only the shooting skills of the Volunteers but also of rifle shooters generally. By holding regular competitions the hope was to make shooting as popular as other British sporting events. With the Prince Consort as Patron and the Duke of Cambridge offering an annual prize, the NRA had very close links with Royalty and the British military establishment.

The appointment of Lord Roberts to the position of Vice-President of the Association in 1901 and the eventual death of the Duke of Cambridge in 1904, had kept the NRA quiet when the SMLE had been adopted. Despite its official position of neutrality in the issue, individual members tended to have very particular views about rifles, and they brought them up in a number of newspapers and journals. Wedded to hitting conventional bull's eye targets at set distances, the association encouraged a view of marksmanship that was invariably at odds with the new demands of the battlefields of South-West Frontier and South Africa.

As far as the NRA's membership was concerned, the key ability of a good service rifle was the capability of accurately striking targets out to long range distances. Accordingly, members took a dim view of the SMLE because it did not fit with their ideas on marksmanship and rifle design. In particular they were not happy with the shortness of the rifle, the lack of a wind gauge for the rear sight and the suitability of cordite ammunition for target shooting.

By 1908 they had found their new favourite, and influential political forces were soon once again at work to influence the procurement decisions of the British military.

Last edited:

Chapter 253: The Rifle Question, Part V: Royal Endorsement

He had returned from South Africa with a firm conviction: a small-bore bullet fired at high velocity was clearly the way forward. The Austrian, von Mannlicher, had clearly been right: the ideal bullet diameter was .280, with a 150-grain bullet. The muzzle velocity would have to reach the magical plateau of 3,000 fps. It would have to be rimless, slightly larger than the 7x57 currently in military use.

The man hired to turn this vision into reality as a consultant was one of the best experts available in the entire world, “the father of smokeless powder” - even though his methods merely opened ways for further development. Frederick W. Jones had patented a method of coating smokeless powders to regulate their burning rate, and had worked for Nobel, Imperial Chemical Industries, New Explosives Company, Eley Brothers and the British government.

Combining theory and practice, Mr. Jones was a distinguished member of a high-level competition rifle shooting club competing in the the English Elcho Shield, a competition shot at 1000, 1100 and 1200 yards.

His initial testing of the .28/06 with a 150-grain bullet recorded a muzzle velocity of 2,735fps, a marked improvement over the .275. Then the case was lengthened and the base was widened a bit, improving the taper. By 1907 a new .280 ammunition was ready for production. Eley Brothers were happy to produce it for him, since the business was booming and the new round was in high demand.

Initially a target cartridge, it was designed with military and hunting uses in mind from the start.It triumphed at Bisley in 1908, prompting gunmakers to start chambering hunting rifles for it, as well as developing new competing cartridges. The new magnum action of Mauser worked well with the new round.

Always conscious of the importance of high-profile supporters, the inventor had made good use of his contacts to high society. In 1900 he had presented his rifles to Field Marshall Roberts, and most importantly, to the Prince of Wales. His Imperial Majesty, King George V duly returned the favour and endorsed the .280 cartridge after extensive use during his 1907 grand tour of India, shooting everything from rhinoceros to Bengal tigers.[2] The King used a Lancaster .280 double, for Charles Lancaster & Co. had more royal warrants than any other London gunmaker. And just as it happened, Lancaster was already in a lucrative business contract with the inventor of the new .280.

Sir Charles Ross was now the man of the hour.

2: As the old king dies earlier, the tour happens just before the famous success of .280 at Bisley in 1908.

Chapter 254: The Rifle Question, Part VI: Marksmanship above all

Adding to the .303 only the simplest possible mechanism for quick loading as a temporary measure, while embarking at once on a rifle more up-to-date in certain respects at a much increased cost was a risky decision. We will never know whether the converted SMLE would have lasted us satisfactorily till yet greater changes had begun to press? Such questions as these are not easily answered with certainty, since they imply a correct judgement of the future, yet upon a right answer to them much may depend.[1]

British Small Arms Committee made two important decisions in early 1907:

President (ex officio): Colonel Charles Monro, The Commandant of the School of Musketry at Hythe. Monro was a high-flier appointed by Roberts to follow Ian Hamilton, an influential musketry drill reformer and another member of his Indian entourage. A self-declared "musketry maniac", Monro stressed the importance of infantry marksmanship with relentless vigour.

Another key member was the Chief Inspector of Small Arms, Lt-Colonel John Hopton. Hopton was one of the greatest rifle shots of his day, an Olympic Marksman at the 1000 yard free rifle event 1908 (his ranking there was 24th out of 50).[2]

The Naval Member, Col. Pease, had little influence to this decision.

The Military Members represented the three most influential groups within the British Armed forces: Major McEven for Cavalry, Major Matheson for Infantry, and Lt.-Col. Fremantle for Auxiliary Forces.

Out of the three, Fremantle had the highest rank and most clout, since he was the former Assistant Private Secretary to former War Minister St John Brodrick.

Fremantle had published three books on the subject of rifle shooting, had shot in the English Eight for years. He had also competed in the 1000 yard free rifle event at the 1908 Summer Olympics with Hopton (16th out of 50).

The Secretary, Captain Douglas of Royal Artillery, had his own views. As the RA was already getting a massive share of the available Army funds, his influence was however rather limited.

Increasingly worried that the German Gewehr 98 and the US M1903 Springfield developed considerably greater muzzle velocity than the short Lee-Enfield, the British Small Arms Committee was asked to list features to be incorporated into an entirely new rifle. The Germans had already introduced a spitzer-type S Patrone, and had by 1905 replaced their older Patrone 88 as the primary ammunition of their infantry weapons. Seen at the light of the recent war in Scandinavia, the British Small Arms Committee concluded that instead of reforming the old .303, Britain would have to upgrade not only the ammunition but the rifle as well.[3]

In their final report in 1910 the Committee concluded that as much of the SMLE was to be retained as possible, but a Mauser-pattern action was to be used, and an aperture backsight substituted for the open notch. An experimental .276-calibre cartridge was being recommended for field trials early to replace the rimmed .303. Shooting new rimless, or cannelured cartridges instead of the rimmed .303, the new caliber was called .276 or .280, showing the clear similarity to the .280 " cartridge of Sir Charles Ross .

The engineers of the Enfield company dutifully took these design specs and went to work.

With a swept-back bolt handle placed close to the trigger, the design aimed to produce a weapon capable of great volume of rapid rifle fire. The fact that continental armies were beginning to wear khaki uniforms, fight from cover and use artillery and machine guns to provide their volume of fire did not diminish the British desire for a weapon capable of delivering the type of infantry firepower that had defined the Boer War and stopped the Mahdist forces cold at the battle of Omdurman in 1898.

Closing stroke of the bolt completed most of the cocking action of the firing mechanism. Whereas Mausers used the opening action of the bolt to cock the piece, the British designers (being no strangers to gritty or sandy conditions of colonial campaigns) felt that the full force on the opening stroke should be reserved for extracting the fired cartridge case.

As the new Enfield rifle and modern ammunition for it were being tested, the truce achieved within the Army brass by the adoption of the SMLE was now broken. The Cavalry faction was now out for blood.

1. Another OTL quote from Major T. F. Fremantle, 1st Bucks Volunteer Rifle Corps

2: To say that this guy was a marksmanship ethusiast is an understatement: his mausoleum allegedly marks the spot from which he once hit the bulls-eye of a target 1500 yards away...

3. In OTL the Small Arms Committee recommended the adoption of the new bullet for the British Service as a temporary expedient pending the introduction of an entirely new design of rifle and ammunition. This had a lot to do with the fact that northern France was now the planned OTL battlefield, and all planning and procurement was made accordingly.

TTL the different Army reforms, the "gravel-belly" lobby of Fremantle and Hopton within the Small Arms Committee, the strong Volunteer background of both War Minister Dilke and PM Spencer and the Royal preference for .280 Ross (not to mention the Liberal reluctance towards all forms of military spending) all combine into a decision that deviates from OTL decision to procure the Mark VII spitzer ammunition as a further upgrade to the SMLE that many prewar OTL critics viewed as an anachronistic stopgap weapon.

British Small Arms Committee made two important decisions in early 1907:

- some form of standardization of existing rifles was in order

- there was a need for an entirely new rifle that would incorporate the lessons of the war.

President (ex officio): Colonel Charles Monro, The Commandant of the School of Musketry at Hythe. Monro was a high-flier appointed by Roberts to follow Ian Hamilton, an influential musketry drill reformer and another member of his Indian entourage. A self-declared "musketry maniac", Monro stressed the importance of infantry marksmanship with relentless vigour.

Another key member was the Chief Inspector of Small Arms, Lt-Colonel John Hopton. Hopton was one of the greatest rifle shots of his day, an Olympic Marksman at the 1000 yard free rifle event 1908 (his ranking there was 24th out of 50).[2]

The Naval Member, Col. Pease, had little influence to this decision.

The Military Members represented the three most influential groups within the British Armed forces: Major McEven for Cavalry, Major Matheson for Infantry, and Lt.-Col. Fremantle for Auxiliary Forces.

Out of the three, Fremantle had the highest rank and most clout, since he was the former Assistant Private Secretary to former War Minister St John Brodrick.

Fremantle had published three books on the subject of rifle shooting, had shot in the English Eight for years. He had also competed in the 1000 yard free rifle event at the 1908 Summer Olympics with Hopton (16th out of 50).

The Secretary, Captain Douglas of Royal Artillery, had his own views. As the RA was already getting a massive share of the available Army funds, his influence was however rather limited.

Increasingly worried that the German Gewehr 98 and the US M1903 Springfield developed considerably greater muzzle velocity than the short Lee-Enfield, the British Small Arms Committee was asked to list features to be incorporated into an entirely new rifle. The Germans had already introduced a spitzer-type S Patrone, and had by 1905 replaced their older Patrone 88 as the primary ammunition of their infantry weapons. Seen at the light of the recent war in Scandinavia, the British Small Arms Committee concluded that instead of reforming the old .303, Britain would have to upgrade not only the ammunition but the rifle as well.[3]

In their final report in 1910 the Committee concluded that as much of the SMLE was to be retained as possible, but a Mauser-pattern action was to be used, and an aperture backsight substituted for the open notch. An experimental .276-calibre cartridge was being recommended for field trials early to replace the rimmed .303. Shooting new rimless, or cannelured cartridges instead of the rimmed .303, the new caliber was called .276 or .280, showing the clear similarity to the .280 " cartridge of Sir Charles Ross .

The engineers of the Enfield company dutifully took these design specs and went to work.

With a swept-back bolt handle placed close to the trigger, the design aimed to produce a weapon capable of great volume of rapid rifle fire. The fact that continental armies were beginning to wear khaki uniforms, fight from cover and use artillery and machine guns to provide their volume of fire did not diminish the British desire for a weapon capable of delivering the type of infantry firepower that had defined the Boer War and stopped the Mahdist forces cold at the battle of Omdurman in 1898.

Closing stroke of the bolt completed most of the cocking action of the firing mechanism. Whereas Mausers used the opening action of the bolt to cock the piece, the British designers (being no strangers to gritty or sandy conditions of colonial campaigns) felt that the full force on the opening stroke should be reserved for extracting the fired cartridge case.

As the new Enfield rifle and modern ammunition for it were being tested, the truce achieved within the Army brass by the adoption of the SMLE was now broken. The Cavalry faction was now out for blood.

1. Another OTL quote from Major T. F. Fremantle, 1st Bucks Volunteer Rifle Corps

2: To say that this guy was a marksmanship ethusiast is an understatement: his mausoleum allegedly marks the spot from which he once hit the bulls-eye of a target 1500 yards away...

3. In OTL the Small Arms Committee recommended the adoption of the new bullet for the British Service as a temporary expedient pending the introduction of an entirely new design of rifle and ammunition. This had a lot to do with the fact that northern France was now the planned OTL battlefield, and all planning and procurement was made accordingly.

TTL the different Army reforms, the "gravel-belly" lobby of Fremantle and Hopton within the Small Arms Committee, the strong Volunteer background of both War Minister Dilke and PM Spencer and the Royal preference for .280 Ross (not to mention the Liberal reluctance towards all forms of military spending) all combine into a decision that deviates from OTL decision to procure the Mark VII spitzer ammunition as a further upgrade to the SMLE that many prewar OTL critics viewed as an anachronistic stopgap weapon.

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: