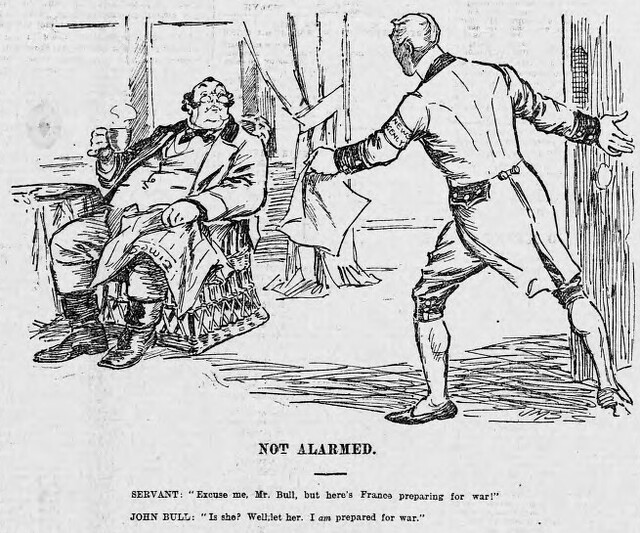

Engineers, chemists, sportsman shooters, expert marksmen, infantrymen and cavalrymen. Historians, military theorists, generals - and the common soldier.

Not to mention the self-proclaimed experts at the press and the man on the street. Everyone had an opinion when it came to the topic of modern military rifles.

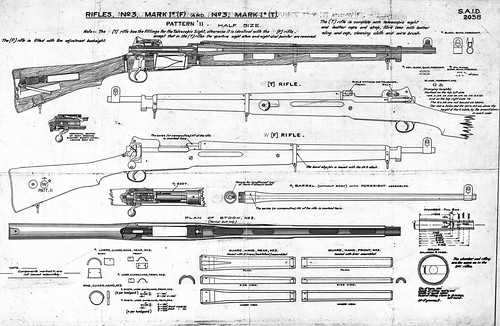

It all started from the measurements. Every ounce of weight had to be taken into consideration, for weight saved in the arm could be added to the ammunition and other equipment carried.

At the same time the rifle had to be obviously strong enough to stand rough usage and strain of bayonet fighting. The older rifles had been longer partially to make them better for bayonet work, but also to enable for rank firing in close order.

Bolt actions had become universal, but aside from that several features separated the similar-ish rifles of the armies of the world from one another. A straight pull action, such as in the Austrian or Swiss rifles, or a turning bolt?

A box magazine - a narrow or deep one, with a single or double row of cartridges? And with a cut-off or maybe even a horizontal Krag-Jorgensen type box with a trapdoor in the side of the rifle?

A charger system or a clip magazine? How many cartridges per clip?

A box magazine, bolt action and the placement of the breech action all curtailed the size of the barrel. The barrel had an important bearing on the velocity.

And the cartridges, oh! Rimmed cartridges took up more room in packing than rimless ones. They were also more liable to jam.

Rimless cartridges had nothing more than the taper at the neck and the extractor hook preventing them being accidentally forced too far forward into the chamber.

And their propellant! The legendary cordite had survived much criticism. It imparted high velocity for bullets fired from shorter barrels than before in a way that had been impossible with black powder.

It had many merits: it was stable, efficient, very controllable and trustworthy in all climates of the British Empire.

Excessive barrel erosion, its chief drawback, was lately being greatly diminished with modified mixture containing only 30% of nitroglycerin instead of the old 58%.

With the propellant debate more or less settled, there was the question of bullet velocity: the designers were after the "impossible ideal" of a bullet travelling for 3 000 yards in a straight line and then dropping to the ground.

Penetration and force of blow of the bullet were of course important as well. But the experts agreed that the main difficulty for efficient musketry in a modern war was that of adjusting the aim to the distance of the mark.

As long as range finding remained little more than a matter of guesswork, the importance of a flat trajectory was enormous, for it diminished the necessity of accurate guessing.

But higher velocity could only achieved by larger flow of gases under increased pressure. As charges in the cartridge grew, pressures were increased in turn.

This could only be avoided by an equal increase in the capacity of the cartridge to achieve a reduced gravimetric density.

If the pressures were to be kept within reasonable limits, the cartridge had to be enlarged to an awkward shape, while the barrel necessarily suffered more from the action of the gases and the bullet upon it.

The caliber was really the crux of the matter.