But without czechia or central poland, polandslovakia is unsustainable and is gonna get molotov-ribentrop'ed in a few years.You mean the country who joined the war in the last few months, only to fight two battles and then conclude an armistice over her allies' heads and which undermined their overall war aims? Damn right the Entente (especially the UK) weren't going to just hand Italy all of its territorial demands. Whatever else you think about the Habsburg's (and who doesn't), if they can hold together a good portion of central/eastern Europe then the rest of the Entente is kind of happy to keep them around: the UK wants to preserve the balance of power; the French don't blame them anything like as much as the Germans; the US just wants to GTFO of Europe; and the Russians aren't bothered because they think that all these other countries are going to be swept away by a revolution in the next decade or so anyway.

But, to be more serious for a second, I agree that this is a bit ASB, to say the least, especially considering that there hasn't been a substantial POD ITTL before the war. However, I don't think it's necessarily the case that Austria-Hungary was doomed before the war, rather that it was the fact that the war went so disastrously for them which destroyed them. Pieter Judson makes this case rather convincingly, I think, in his latest book. So if Austria-Hungary has a less disastrous war, then there's a chance it (or at least some of it) might stick around. Anyway, I think that the point is at the very least arguable and, besides, what's the point of having an alt TL if you can't keep the Habsburgs around for a bit longer?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Anglo-Saxon Social Model

- Thread starter Rattigan

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030But without czechia or central poland, polandslovakia is unsustainable and is gonna get molotov-ribentrop'ed in a few years.

I mean, don’t expect this configuration of a Polish and Slovakian state to be celebrating its 50th anniversary...

It’s the bad result of a bad compromise...

Than why would the victors let it happen than? Even if USA doesnt care, I am pretty shure both UK and France care about not having unsustainable states around to feed either revanchist germany or the USSR in a few years or months. Is far more likely that they would presure austria and czechia to have zcechia as part of the union. This would mean basically Czechoslovakia with all of poland minus Congress Poland, I guess it controls the polish corridor so it has a baltic port. I guess the have a Kingdom of Croats, Serbs and slovenians style name and get later renamed Zapadoslavia or something.I mean, don’t expect this configuration of a Polish and Slovakian state to be celebrating its 50th anniversary...

It’s the bad result of a bad compromise...

Basically poland-slovakia is too obviously not viable and I dont think France and England would let such a week state go just next to germany and the Bolsheviks. Also what happen with the part of Croatia that wasnt annex by Serbia?

Than why would the victors let it happen than? Even if USA doesnt care, I am pretty shure both UK and France care about not having unsustainable states around to feed either revanchist germany or the USSR in a few years or months. Is far more likely that they would presure austria and czechia to have zcechia as part of the union. This would mean basically Czechoslovakia with all of poland minus Congress Poland, I guess it controls the polish corridor so it has a baltic port. I guess the have a Kingdom of Croats, Serbs and slovenians style name and get later renamed Zapadoslavia or something.

Basically poland-slovakia is too obviously not viable and I dont think France and England would let such a week state go just next to germany and the Bolsheviks. Also what happen with the part of Croatia that wasnt annex by Serbia?

I don’t consider it improbable at all. I think it’s exactly the kind of mess that a collective with contradictory objectives (to punish Germany and Austria: to keep both those countries around to preserve a balance of power: to create a Polish homeland: not to take territory from Russia) would come to. Sure, if you put the French alone in a room for six months they'd come up with a more coherent peace treaty but the fact is that history (or TTL's history) didn't do that. None of the victors could just sit down and impose its will on the others so the end result is a bit of a mess. And, to recapitulate a point a bit, the borders of the OTL Second Polish Republic weren't exactly that 'sustainable', hence why they only lasted 20 years. Peace treaties (or any agreement, really) which attempt to compromise between irreconcilable positions often produce results which neither party is exactly happy with. And as we'll see when I focus back on the UK again, one of the British foreign policy aims heading into the 20s will be to try and iron out what they see as the problems with the Paris Treaty (either through the League or unilaterally).

BigBlueBox

Banned

@Rattigan

The war ends with Italy occupying Ljubljana, and with far less casualties than OTL. There is simply no way that Italy can walk out of this scenario with less than what they got OTL. In fact, they would probably get more than OTL. If Italian troops are already in Ljubljana when Austria sues for peace then the armistice conditions certainly includes Italian occupation of all Slovenia. Is Britain going to go to war with Italy if the Italians simply annex their claimed lands without approval from the rest of the Entente? If not, then Italy is getting what it wants. Oh, and Franz Ferdinand will gladly sell out Slovenia if it means keeping South Tyrol. In OTL the Czechs declared independence during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Promises of federalization or autonomy are far too little, far too late to stop them from doing the same ITTL. The only way Austria is leaving the peace table with Czech Bohemia is if the whole Entente gives them two thumbs up to subjugate the Czechs with military force. I don’t think that’s likely.

The war ends with Italy occupying Ljubljana, and with far less casualties than OTL. There is simply no way that Italy can walk out of this scenario with less than what they got OTL. In fact, they would probably get more than OTL. If Italian troops are already in Ljubljana when Austria sues for peace then the armistice conditions certainly includes Italian occupation of all Slovenia. Is Britain going to go to war with Italy if the Italians simply annex their claimed lands without approval from the rest of the Entente? If not, then Italy is getting what it wants. Oh, and Franz Ferdinand will gladly sell out Slovenia if it means keeping South Tyrol. In OTL the Czechs declared independence during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Promises of federalization or autonomy are far too little, far too late to stop them from doing the same ITTL. The only way Austria is leaving the peace table with Czech Bohemia is if the whole Entente gives them two thumbs up to subjugate the Czechs with military force. I don’t think that’s likely.

@Rattigan

The war ends with Italy occupying Ljubljana, and with far less casualties than OTL. There is simply no way that Italy can walk out of this scenario with less than what they got OTL. In fact, they would probably get more than OTL. If Italian troops are already in Ljubljana when Austria sues for peace then the armistice conditions certainly includes Italian occupation of all Slovenia. Is Britain going to go to war with Italy if the Italians simply annex their claimed lands without approval from the rest of the Entente? If not, then Italy is getting what it wants. Oh, and Franz Ferdinand will gladly sell out Slovenia if it means keeping South Tyrol. In OTL the Czechs declared independence during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Promises of federalization or autonomy are far too little, far too late to stop them from doing the same ITTL. The only way Austria is leaving the peace table with Czech Bohemia is if the whole Entente gives them two thumbs up to subjugate the Czechs with military force. I don’t think that’s likely.

The Italy-Austria bit still has some way to go. The Italians aren't happy with the Paris Treaty. And the question of whether the British/League of Nations will go to war to protect Austrian control of Slovenia is going to be a live one for a while. Also worth remembering that, while Italy are definitely in a stronger position militarily ITTL, they're in a much weaker position diplomatically, because they're seen to have only joined opportunistically and been an unreliable ally. So, from the Italian POV, is it worth risking a war with Britain, France and Russia just to preserve their hold over Slovenia? Cuts both ways, at the very least.

While I appreciate that the terms of the Paris Treaty has caused a bit of controversy on this thread, please bear with me because that's not an accident. It's meant to be a horrible mess of a treaty and I have plans for it in the future.

OTL's Versailles was also a mess for largely the same reasons.

Czech-Slovakia and Yugoslavia were hamfisted fusions for the same half-hearted attempts to create stability and counterweights.

Poland was given German territory, saddled with a German enclave, and the Danzig corridor.

I've seen the same thing in company strategy meetings, people aren't always completely rational automatons. Fudge a project in three different, contradictory, ways to satisfy three pet desires and suddenly the project is so fudged it could never accomplish its original intent. But if you don't satisfy those three people it can't proceed, so on it shambles; the people doing the fudging hoping it can still get somewhere productive.

Czech-Slovakia and Yugoslavia were hamfisted fusions for the same half-hearted attempts to create stability and counterweights.

Poland was given German territory, saddled with a German enclave, and the Danzig corridor.

I've seen the same thing in company strategy meetings, people aren't always completely rational automatons. Fudge a project in three different, contradictory, ways to satisfy three pet desires and suddenly the project is so fudged it could never accomplish its original intent. But if you don't satisfy those three people it can't proceed, so on it shambles; the people doing the fudging hoping it can still get somewhere productive.

Revolutions, 1918 - 1922

A World Revolution?: Russian Foreign Policy in Europe, 1918-1922

The faces of revolution: (l to r) Bavarian cavalry re-occupy Munich; Bela Kun addresses crowds in Budapest; Mustapha Kemal directs his staff in 1922

The attitude of the Russian delegation was one of the more hotly anticipated and unknowable factors about the Paris Peace Conference. In the context of fighting a war, the British, French and Americans had bent over backwards to keep Russia’s new communist government in the war, including taking actions which explicitly shored up the new regime. Despite this, few in London, Paris or Philadelphia fully trusted them and this was only underlined when Trotsky published his initial bargaining position in the newspaper ‘Pravda’ in September 1918. The most eye-catching proposal was for self-determination for national minorities, which was commonly understood as a challenge to both Europe’s continental multi-ethnic empires and countries with overseas colonies. However, when it became clear that there was no question of independence for its national minorities in the Baltic, or of Russian Poland being seceded to the new Polish-Slovak Republic, these concerns dissipated. (Sir Maurice Hankey, a senior civil servant and aide to Lloyd George, wrote in his diary that “Mr. Trotsky’s view is that the peoples of the world have the right to self-determination, provided that these rights are exercised sparingly and under close supervision.”) Instead, the Russian and the British delegations formed an unlikely partnership, keeping a check on the more extreme French demands while ensuring that the Entente got paid back for the war as much as was possible.

When the Paris Treaty was eventually signed, Trotsky could look at it with a large degree of satisfaction. He had failed to secure the complete dismemberment of Germany and the Habsburgs in Europe but steps had been taken towards this end nonetheless and the Ottoman Empire was, more or less, a dead letter. This left smaller, weaker, poorer states populating central and eastern Europe, countries ripe for the exportation of Russia’s revolution. Trotsky had staked much of his reputation, including his collaboration with the bourgeois imperialist Entente, on the idea that the Paris Treaty would eventually produce smaller nations crying out for revolution.

The first such country to test this theory was Germany, which was suffering under the linked crises of Entente occupation, war reparations and economic and food shortages. The abdication of Wilhelm II (followed by his death of Spanish flu only a few months later) had only partially appeased a restive population and the alliance between the Prussian Junker class which dominated the military and the bourgeois elements which, by and large, controlled the levers of civil political power, was tenuous at best. On 5 June 1919, the radical Communist Party of Germany launched a coup which attempted to oust the civilian government of Max von Baden and replace it with a council republic along the lines of Russia. The provisional government struggled for legitimacy outside of Berlin, however, and was overthrown only ten days later, when Erich Ludendorff arrived in the city with the Freikorps (a paramilitary made up of demobilized Great War soldiers and using military stock), which then reconquered the city in a battle which resulted in the deaths of 156 communist insurgents.

However, despite this failure, revolutions continued to burst into life across the continent once the punitive final terms of the Paris Treaty had been revealed. In particular, violent street protests broke out across Hungary, focused on Budapest. Following the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy in July 1918, the new Hungarian government had imprisoned members of the Hungarian Communist Party until July 1919, when they were progressively released. However, rather than becoming ordinary, if extreme, members of a parliamentary government, the Communists instead followed the Bolshevik programme and proclaimed a socialist republic on 21 August. One month later, the Bolshevik-backed Independent Social Democratic Party of Bavaria responded to its failure to score an electoral breakthrough in the September 1919 legislative elections by taking advantage of King Rupprecht’s absence from Munich to launch a coup. A similar uprising in Vienna was crushed swiftly without seizing control of any levers of power.

While the insurgents in Munich and Budapest seemed to have the authorities in checkmate, the reality was a lot more complicated. In neither country, for example, did they manage to gain the loyalty of the army. Drawing on his experience during the Great War, Rupprecht was able to rally troops to his side and recapture Munich only a month after he had lost it. Although the Hungarian Social Republic managed to hold out longer, they too faced continued insurgency from conservative forces within their own country. Furthermore, when it became clear that Russia was unwilling to re-open the question of the borders set by the Paris Treaty, the new Hungarian government was forced to publicly acquiesce to its terms, which caused it to lose virtually all of its remaining internal support. The remnants of the Social Republic were then removed from power on New Year’s Day 1920, when Admiral Horthy’s troops entered Budapest.

While Trotsky’s revolutions collapsed underneath him in Europe, a new and more complicated one had broken out in Asia Minor. Although its state had completely collapsed under the weight of fighting the Great War, the Ottoman elite still commanded a substantial amount of historical-based loyalty. In January 1920, Sefik Pasha seized control of what remained of the Ottoman government and began a war to try and re-write the Paris Treaty. He found himself opposed not only by Greek and Bulgarian forces but also by Russian-backed communists (lead by Mustafa Suphi), pan-Turkish nationalists (lead by Enver Pasha) and liberal modernisers (lead by Mustafa Kemal).

The fighting over Asia Minor moved from side to side until late 1921, when the British government began to back Kemal’s forces (moving from its previous position of supporting the Greeks and Bulgarians). In secret discussions with the Russians and the Armenians, Kemal agreed to accept their aid in return for mild redrawings of the Paris Treaty and ceasing attacks on Bulgaria and Greece for the time being. This, in turn, lead to Trotsky deciding to withdraw support for Suphi and backing Kemal instead, reasoning that Kemal was a figure who could be bent to the Russians’ will if they got in early. With this new configuration of support, Kemal was able to defeat his opponents and agree the Treaty of Kars in May 1922. By this treaty, Greece returned much of the territory it had been awarded in the Aegean (leaving them with Smyrna and the surrounding area – which was a territory which the Greeks were far more comfortable holding anyway) and the Entente agreed to time-limit the demilitarized zone on the Asian side of Marmara. In return, the newly-proclaimed Republic of Turkey agreed to recognize Armenia’s, Greece’s, Bulgaria’s and Arabia’s new borders. A separate annex of the treaty between Armenia and Russia firmly defined the borders between Armenian and Russian territory in the Caucuses.

Although the failures of these revolutions had not, ultimately, cost Russia anything, they were clearly a political disaster for Trotsky. At the 10th Party Congress in the summer of 1921, he was removed from his position as Foreign Secretary and would remain out of power until 1924. Although Soviet-Turkish relations would be warm for many years, the failure of these revolutions had confirmed the survival of the aristocratic and genteel bourgeois alliance in power in central and eastern Europe. Despite the heady hopes of 1917-18, the revolution had clearly come to a halt within Russia’s borders.

The faces of revolution: (l to r) Bavarian cavalry re-occupy Munich; Bela Kun addresses crowds in Budapest; Mustapha Kemal directs his staff in 1922

The attitude of the Russian delegation was one of the more hotly anticipated and unknowable factors about the Paris Peace Conference. In the context of fighting a war, the British, French and Americans had bent over backwards to keep Russia’s new communist government in the war, including taking actions which explicitly shored up the new regime. Despite this, few in London, Paris or Philadelphia fully trusted them and this was only underlined when Trotsky published his initial bargaining position in the newspaper ‘Pravda’ in September 1918. The most eye-catching proposal was for self-determination for national minorities, which was commonly understood as a challenge to both Europe’s continental multi-ethnic empires and countries with overseas colonies. However, when it became clear that there was no question of independence for its national minorities in the Baltic, or of Russian Poland being seceded to the new Polish-Slovak Republic, these concerns dissipated. (Sir Maurice Hankey, a senior civil servant and aide to Lloyd George, wrote in his diary that “Mr. Trotsky’s view is that the peoples of the world have the right to self-determination, provided that these rights are exercised sparingly and under close supervision.”) Instead, the Russian and the British delegations formed an unlikely partnership, keeping a check on the more extreme French demands while ensuring that the Entente got paid back for the war as much as was possible.

When the Paris Treaty was eventually signed, Trotsky could look at it with a large degree of satisfaction. He had failed to secure the complete dismemberment of Germany and the Habsburgs in Europe but steps had been taken towards this end nonetheless and the Ottoman Empire was, more or less, a dead letter. This left smaller, weaker, poorer states populating central and eastern Europe, countries ripe for the exportation of Russia’s revolution. Trotsky had staked much of his reputation, including his collaboration with the bourgeois imperialist Entente, on the idea that the Paris Treaty would eventually produce smaller nations crying out for revolution.

The first such country to test this theory was Germany, which was suffering under the linked crises of Entente occupation, war reparations and economic and food shortages. The abdication of Wilhelm II (followed by his death of Spanish flu only a few months later) had only partially appeased a restive population and the alliance between the Prussian Junker class which dominated the military and the bourgeois elements which, by and large, controlled the levers of civil political power, was tenuous at best. On 5 June 1919, the radical Communist Party of Germany launched a coup which attempted to oust the civilian government of Max von Baden and replace it with a council republic along the lines of Russia. The provisional government struggled for legitimacy outside of Berlin, however, and was overthrown only ten days later, when Erich Ludendorff arrived in the city with the Freikorps (a paramilitary made up of demobilized Great War soldiers and using military stock), which then reconquered the city in a battle which resulted in the deaths of 156 communist insurgents.

However, despite this failure, revolutions continued to burst into life across the continent once the punitive final terms of the Paris Treaty had been revealed. In particular, violent street protests broke out across Hungary, focused on Budapest. Following the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy in July 1918, the new Hungarian government had imprisoned members of the Hungarian Communist Party until July 1919, when they were progressively released. However, rather than becoming ordinary, if extreme, members of a parliamentary government, the Communists instead followed the Bolshevik programme and proclaimed a socialist republic on 21 August. One month later, the Bolshevik-backed Independent Social Democratic Party of Bavaria responded to its failure to score an electoral breakthrough in the September 1919 legislative elections by taking advantage of King Rupprecht’s absence from Munich to launch a coup. A similar uprising in Vienna was crushed swiftly without seizing control of any levers of power.

While the insurgents in Munich and Budapest seemed to have the authorities in checkmate, the reality was a lot more complicated. In neither country, for example, did they manage to gain the loyalty of the army. Drawing on his experience during the Great War, Rupprecht was able to rally troops to his side and recapture Munich only a month after he had lost it. Although the Hungarian Social Republic managed to hold out longer, they too faced continued insurgency from conservative forces within their own country. Furthermore, when it became clear that Russia was unwilling to re-open the question of the borders set by the Paris Treaty, the new Hungarian government was forced to publicly acquiesce to its terms, which caused it to lose virtually all of its remaining internal support. The remnants of the Social Republic were then removed from power on New Year’s Day 1920, when Admiral Horthy’s troops entered Budapest.

While Trotsky’s revolutions collapsed underneath him in Europe, a new and more complicated one had broken out in Asia Minor. Although its state had completely collapsed under the weight of fighting the Great War, the Ottoman elite still commanded a substantial amount of historical-based loyalty. In January 1920, Sefik Pasha seized control of what remained of the Ottoman government and began a war to try and re-write the Paris Treaty. He found himself opposed not only by Greek and Bulgarian forces but also by Russian-backed communists (lead by Mustafa Suphi), pan-Turkish nationalists (lead by Enver Pasha) and liberal modernisers (lead by Mustafa Kemal).

The fighting over Asia Minor moved from side to side until late 1921, when the British government began to back Kemal’s forces (moving from its previous position of supporting the Greeks and Bulgarians). In secret discussions with the Russians and the Armenians, Kemal agreed to accept their aid in return for mild redrawings of the Paris Treaty and ceasing attacks on Bulgaria and Greece for the time being. This, in turn, lead to Trotsky deciding to withdraw support for Suphi and backing Kemal instead, reasoning that Kemal was a figure who could be bent to the Russians’ will if they got in early. With this new configuration of support, Kemal was able to defeat his opponents and agree the Treaty of Kars in May 1922. By this treaty, Greece returned much of the territory it had been awarded in the Aegean (leaving them with Smyrna and the surrounding area – which was a territory which the Greeks were far more comfortable holding anyway) and the Entente agreed to time-limit the demilitarized zone on the Asian side of Marmara. In return, the newly-proclaimed Republic of Turkey agreed to recognize Armenia’s, Greece’s, Bulgaria’s and Arabia’s new borders. A separate annex of the treaty between Armenia and Russia firmly defined the borders between Armenian and Russian territory in the Caucuses.

Although the failures of these revolutions had not, ultimately, cost Russia anything, they were clearly a political disaster for Trotsky. At the 10th Party Congress in the summer of 1921, he was removed from his position as Foreign Secretary and would remain out of power until 1924. Although Soviet-Turkish relations would be warm for many years, the failure of these revolutions had confirmed the survival of the aristocratic and genteel bourgeois alliance in power in central and eastern Europe. Despite the heady hopes of 1917-18, the revolution had clearly come to a halt within Russia’s borders.

Great update! A map would be nice, just to visualize the differences between OTL and TTL.

To give you an idea of where my IT skills are generally, I've only just gotten around to starting to create infoboxes but I'll definitely try and get on this when I have the opportunity/have learned the relevant skills.

Oh right, Italy has basically ended the war with just less than the 1% of death in OTL WWI and basically avoided the destruction of Veneto due to the A-H occupation, plus the general social strife due to the war will be nothing comparated to OTL due to how short and relatevely inexpensive the war was.

So...no, Italy will not give up Istria to Jugoslavia, at least not everything and this in the worst case scenario, expecially not Trieste and Gorizia, not while they occupy the entire zone and frankly the diplomatic and economic way to pressure her are much much less than OTL as it's basically the less spent of the big boys.

Frankly in this scenario while South Tyrol can be left out, in exchange of a favorable military border in Trentino and at least a demilitarizated zone on the Austrian side...Istria cannot be left out, no goverment will survive more than 5 second if it allow Jugoslavia to inglobe everything, expecially with the italian military in a much stronger position than OTL.

Regarding the armistice, well frankly the situation it's not very different from OTL, the armistice between Italy (for the entente) and A-H was not a multinational affair it was just between Rome and Wien with the rest of the allies just informed of the act and term, in this case there are also the Romanian because the bulk of the effort against A-H at the moment is done by Italy and Romania and the terms are more or less what expect and trough italian effort Bavaria is no more part of the German empire...so Rome will probably expect a big thank you instead of a temper tantrum because some feeling has been hurt.

The italian goverment, unless has entered the war on his own, without being formally a member of the entente (and in this case the armistice will be even more an italian only matter), had already discuss the compensation with the rest of the entente and will expect the application of such treaty; Dalmatia can be left out, but at least Zara and Sebenico plus some islands of Dalmatia will be demanded, also Istria (with more or less the OTL border) even if in this case give up Fiume to Jugoslavia or keep it as a free state will be much more easier, same for Albania (it's too strategically important for Italy to leave her alone) or the status of the A-H navy and merchant fleet.

They see Italy as an opportunistic ally of the last moment (so more or less like OTL), maybe she is...unfortunely she had a lot of success and delivered what she promised and even more and basically without help from his allies, so not many point of pressure there; it will create diplomatic tension post-war? Probably, but at the moment i doubt that the British pubblic is ok in launching a war against an ally (still very fresh in term of war capacity) for the sake of an enemy that has just surrender because they don't want to apply a previous agreement.

In OTL Wilson pressure were succesfull due to the economic and social situation of Italy, the weakness of the goverment due to the internal situation, the enourmous monetary debt and the importance of american loan...here, not that much

So...no, Italy will not give up Istria to Jugoslavia, at least not everything and this in the worst case scenario, expecially not Trieste and Gorizia, not while they occupy the entire zone and frankly the diplomatic and economic way to pressure her are much much less than OTL as it's basically the less spent of the big boys.

Frankly in this scenario while South Tyrol can be left out, in exchange of a favorable military border in Trentino and at least a demilitarizated zone on the Austrian side...Istria cannot be left out, no goverment will survive more than 5 second if it allow Jugoslavia to inglobe everything, expecially with the italian military in a much stronger position than OTL.

Regarding the armistice, well frankly the situation it's not very different from OTL, the armistice between Italy (for the entente) and A-H was not a multinational affair it was just between Rome and Wien with the rest of the allies just informed of the act and term, in this case there are also the Romanian because the bulk of the effort against A-H at the moment is done by Italy and Romania and the terms are more or less what expect and trough italian effort Bavaria is no more part of the German empire...so Rome will probably expect a big thank you instead of a temper tantrum because some feeling has been hurt.

The italian goverment, unless has entered the war on his own, without being formally a member of the entente (and in this case the armistice will be even more an italian only matter), had already discuss the compensation with the rest of the entente and will expect the application of such treaty; Dalmatia can be left out, but at least Zara and Sebenico plus some islands of Dalmatia will be demanded, also Istria (with more or less the OTL border) even if in this case give up Fiume to Jugoslavia or keep it as a free state will be much more easier, same for Albania (it's too strategically important for Italy to leave her alone) or the status of the A-H navy and merchant fleet.

They see Italy as an opportunistic ally of the last moment (so more or less like OTL), maybe she is...unfortunely she had a lot of success and delivered what she promised and even more and basically without help from his allies, so not many point of pressure there; it will create diplomatic tension post-war? Probably, but at the moment i doubt that the British pubblic is ok in launching a war against an ally (still very fresh in term of war capacity) for the sake of an enemy that has just surrender because they don't want to apply a previous agreement.

In OTL Wilson pressure were succesfull due to the economic and social situation of Italy, the weakness of the goverment due to the internal situation, the enourmous monetary debt and the importance of american loan...here, not that much

Dublin Assembly Elections, 1920

The Orange Death of Liberal Ireland: The Dublin Assembly election of 1920

King Edward - Edward Carson addresses a crowd in south Dublin

Following the creation of the Dublin Assembly in the 1880s, elections had been held on a fixed-term basis every five years since 1890. From then, the position of First Minister had been in the hands of Justin McCarthy (1888-1900) and Timothy Healy (1900-1910), both for the Liberals, then Maurice Dockrell (1910-1915) for the Conservatives and then Healy again after 1915.

Following its qualified success in the Westminster elections of 1916, the 1920 Dublin Assembly elections were considered by the Conservatives to be the next opportunity to finesse the Orange Strategy. A particular priority was being able to unite the more explicitly sectarian message directed at Ulster Protestant communities while keeping the support of its wealthy and more genteel (and less politically active since the institution of Home Rule) supporters in the south of Ireland. James Craig had been appointed leader of the Unionists in 1917 in order to shore up the support of Ulster Presbyterians but he was not generally well regarded by the Conservative leadership in London. Carson, in particular, held him in almost total contempt even if they maintained a position of camaraderie in public.

As a result, the 1920 elections saw Carson and Long, both prominent national politicians with close Irish links, take a leading role. Once more, Carson was vital to this presentation, being possibly the one national politician who could talk to conservative and non-Catholic opinion both in and out of Ulster. Since the sectarian riots in Donegal in 1916, the island had seen numerous copycat riots over the following four years, with Catholic protestors smashing Protestant shops or attacking Anglo-Irish-owned manor houses and Protestant mobs doing similar things against Catholic community meetings and even outside Masses.

In truth, the prevalence and violence of these disturbances has probably been exaggerated. Nothing on the scale of the Donegal riots would occur again, for example. Nevertheless, the danger they posed was whipped up by unscrupulous politicians and members of the press, who saw them as serious challenges to their chosen in-groups. In particular, the remnants of Irish republicanism, now generally seen in Celtic revivalist organisations such as the Gaelic Athletic Association, reacted to the isolated outbreaks of violence intemperately. Individuals such as Patrick Pearse and Joseph Plunkett issued calls for armed insurrection in the name of Catholic nationalism, which did not go anywhere with the public but which added heat to the febrile atmosphere.

Throughout the campaign, Carson and Long were able to portray the Conservatives as the party of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval. They appealed to what Carson called the “silent majority”; of socially conservative Irishmen who disliked the violence of the rioters on both sides. Meanwhile, Craig was freer to conduct a more aggressive campaign to sew up Protestant Ulster voters. Craig became an increasingly vocal critic of Catholic social groups, solidifying the Conservatives’ position with the Ulster Protestant right. In the south, Carson was able to mobilise the otherwise generally moribund southern unionist population with his more conciliatory tone. In particular, it was significant when Catholic figures such as the Earl of Kenmare continued to campaign and publicly support the Conservatives.

In the end, the Conservatives swept the Protestant-majority areas of Ulster and scraped together enough seats in Dublin and other bourgeois areas in the south of Ireland to gain 33 seats in the Dublin Assembly, enough for a majority of 2 seats. Labour support held up reasonably well in working class areas in Dublin and Belfast but failed to make any seat gains (the first UK or devolved election in which they had failed to do so), while the Liberals found themselves cornered by the Conservatives’ aggressive campaign messaging. Although Carson was not altogether enthusiastic about Craig’s potential as First Minister, especially with such a narrow, almost meaningless, majority, he pronounced himself “well satisfied” with the result and the same view was taken in Westminster.

King Edward - Edward Carson addresses a crowd in south Dublin

Following the creation of the Dublin Assembly in the 1880s, elections had been held on a fixed-term basis every five years since 1890. From then, the position of First Minister had been in the hands of Justin McCarthy (1888-1900) and Timothy Healy (1900-1910), both for the Liberals, then Maurice Dockrell (1910-1915) for the Conservatives and then Healy again after 1915.

Following its qualified success in the Westminster elections of 1916, the 1920 Dublin Assembly elections were considered by the Conservatives to be the next opportunity to finesse the Orange Strategy. A particular priority was being able to unite the more explicitly sectarian message directed at Ulster Protestant communities while keeping the support of its wealthy and more genteel (and less politically active since the institution of Home Rule) supporters in the south of Ireland. James Craig had been appointed leader of the Unionists in 1917 in order to shore up the support of Ulster Presbyterians but he was not generally well regarded by the Conservative leadership in London. Carson, in particular, held him in almost total contempt even if they maintained a position of camaraderie in public.

As a result, the 1920 elections saw Carson and Long, both prominent national politicians with close Irish links, take a leading role. Once more, Carson was vital to this presentation, being possibly the one national politician who could talk to conservative and non-Catholic opinion both in and out of Ulster. Since the sectarian riots in Donegal in 1916, the island had seen numerous copycat riots over the following four years, with Catholic protestors smashing Protestant shops or attacking Anglo-Irish-owned manor houses and Protestant mobs doing similar things against Catholic community meetings and even outside Masses.

In truth, the prevalence and violence of these disturbances has probably been exaggerated. Nothing on the scale of the Donegal riots would occur again, for example. Nevertheless, the danger they posed was whipped up by unscrupulous politicians and members of the press, who saw them as serious challenges to their chosen in-groups. In particular, the remnants of Irish republicanism, now generally seen in Celtic revivalist organisations such as the Gaelic Athletic Association, reacted to the isolated outbreaks of violence intemperately. Individuals such as Patrick Pearse and Joseph Plunkett issued calls for armed insurrection in the name of Catholic nationalism, which did not go anywhere with the public but which added heat to the febrile atmosphere.

Throughout the campaign, Carson and Long were able to portray the Conservatives as the party of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval. They appealed to what Carson called the “silent majority”; of socially conservative Irishmen who disliked the violence of the rioters on both sides. Meanwhile, Craig was freer to conduct a more aggressive campaign to sew up Protestant Ulster voters. Craig became an increasingly vocal critic of Catholic social groups, solidifying the Conservatives’ position with the Ulster Protestant right. In the south, Carson was able to mobilise the otherwise generally moribund southern unionist population with his more conciliatory tone. In particular, it was significant when Catholic figures such as the Earl of Kenmare continued to campaign and publicly support the Conservatives.

In the end, the Conservatives swept the Protestant-majority areas of Ulster and scraped together enough seats in Dublin and other bourgeois areas in the south of Ireland to gain 33 seats in the Dublin Assembly, enough for a majority of 2 seats. Labour support held up reasonably well in working class areas in Dublin and Belfast but failed to make any seat gains (the first UK or devolved election in which they had failed to do so), while the Liberals found themselves cornered by the Conservatives’ aggressive campaign messaging. Although Carson was not altogether enthusiastic about Craig’s potential as First Minister, especially with such a narrow, almost meaningless, majority, he pronounced himself “well satisfied” with the result and the same view was taken in Westminster.

Last edited:

Second Lloyd George Ministry (1916-1921)

The Old New Liberals: Lloyd George during the Great War and After

David Lloyd George - Although the 'Welsh Wizard' remained much admired, his government was beginning to show its age

When Britain entered the Great War in 1917, the decision was taken to bring members of the opposition parties into the government. While Lloyd George’s control over his own party was near-total, he was distrusted by many members of the Labour frontbench (he was believed to have been the driving force behind the dissolution of the informal Lib-Lab pact in 1911) and widely detested by the Conservatives. Given the fragile Liberal majority after 1916, the feeling in the cabinet was that they could not guarantee the necessary Commons votes on various things, especially if the war went badly. Having some Conservative and Labour ministers in the cabinet would, it was thought, encourage greater cross-party consensus behind the war, not to mention hopefully mean that any negative public reaction would rebound on all parties.

Naturally, this last possibility was a concern for Labour and the Conservatives but politicians from those parties eventually came round to the idea that participation in a coalition would allow them to share some of the praise for a successful war and demonstrate that both parties were responsible for government after over a decade of Liberal hegemony. In the end, two politicians from each party entered the cabinet: for the Conservatives, Hugh Cecil became Under Secretary in the Foreign Office and Edward Carson became Solicitor General; for Labour, Ramsay MacDonald became the first Minister for Labour (with a brief that effectively boiled down to keeping the unions on side for the course of the war) and Phillip Snowden was given the newly created position of First Secretary to the Treasury (effectively deputy Chancellor). The performance of these four was well regarded until Lloyd George terminated the coalition on 12 July 1918.

Despite the enormous human cost of the intense fighting in the year in which the UK fought in the war (around 210,000 dead and 229,000 wounded for the Empire as a whole, 142,000 and 150,000 for the UK itself), there was a perverse way in which the way had improved Britain’s global position, further empowering Britain (and by extension the Empire) as a global power to an extent that was perhaps not fully appreciated at the time. The war loans had further entrenched Britain’s position as the globe’s main creditor nation and war orders had enabled British industry to modernise (particularly in the aeronautics and motor sectors) without having to suffer as much of the attendant human cost as the Americans or the French had had to.

On a military and political level, the speed with which the IEF and EEF had had to be mobilised meant that a variety of different units (Canadian, English, Australian, African etc.) had gone into battle alongside one another. Thus, not only had the closing year of the war demonstrated the effectiveness of the Imperial army’s ‘lightning war’ tactics but had gone further to ideologically draw the scattered peoples of the Dominions into a unified imagined community. Figures from the Dominions, such as Australian career-soldier General Monash and the Irish and Maori soldiers who had served heroically alongside each other at the Battle of Trier, became national heroes across the Empire, creating an opportunity for national expression under the general imperial umbrella.

The remainder of Lloyd George’s premiership is not, however, well regarded by historians. He had resisted entrance in the War as part of an effort to insulate his domestic political programme from the political, social and economic dislocations of war but this had proven in vain. In October 1919, the UK entered a sharp deflationary recession which was to last until June 1921. Wholesale prices collapsed by nearly 40% and unemployment rose from 5% to 9%. Automobile production declined by 60% and industrial production as a whole by 30%. In an attempt to control inflation, the Bank of England increased interest rates. The cause of the crisis has generally been placed at the feet of the end of the War, as factories focused on war production either shut down or retooled themselves and the labour market was disrupted by the return of over 1,500,000 people to the civilian workforce. In response, Lloyd George created the Commission on Unemployment, a cross-party committee made up of businessmen, trades union representatives, civil servants, academics and officials from all parties. The Commission recommended the expansion of Britain’s welfare state as well as further tariffs to protect British (by which was meant, in practice, British and Dominion) industry and agriculture from European and American competition. While these policies did eventually bring down unemployment, they took some time to take effect.

The other main focus of the rest of Lloyd George’s premiership was constitutional affairs. Under the terms of the Life Peerages Act 1920, the Crown was given the power to grant a peerage to any man or woman over the age of 21 to sit in the House of the Lords for life. Although technically granted by the Crown via the New Years Honours List, the Birthday Honours List (to mark the monarch’s official birthday), the Dissolution Honours List (to mark the dissolution of a Parliament) and the Resignation Honours List (to mark the resignation of a Prime Minister), appointments were to be proposed by the Honours Committee (made up of civil servants and members of every party). Additionally, the Government of England Act 1921 finally provided England with a level of devolution comparable to the other nations of the UK. Divided into regions called the West Country, the South East, Greater London, East Anglia, the Midlands, Greater Lancashire and Yorkshire & Humber, with capitals in Bristol, Portsmouth, London, Norwich, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds, respectively.

While the economy climbed out of recession towards the end of summer 1921, the Liberal government could not shake off the impression of age and staleness that hung over it. After over 16 years in government, the same people (more or less) were still sitting around the cabinet table and seemed out of ideas, something only compounded by what was perceived as a weak response to the downturn of 1920. The truth was that it was unlikely that any government could have done anything much more to prevent the economic downturn, all is not fair in economics and politics. Nevertheless, Lloyd George decided to dissolve Parliament in October 1921, attempting to make use of the incipient economic recovery to score a quick victory.

David Lloyd George - Although the 'Welsh Wizard' remained much admired, his government was beginning to show its age

When Britain entered the Great War in 1917, the decision was taken to bring members of the opposition parties into the government. While Lloyd George’s control over his own party was near-total, he was distrusted by many members of the Labour frontbench (he was believed to have been the driving force behind the dissolution of the informal Lib-Lab pact in 1911) and widely detested by the Conservatives. Given the fragile Liberal majority after 1916, the feeling in the cabinet was that they could not guarantee the necessary Commons votes on various things, especially if the war went badly. Having some Conservative and Labour ministers in the cabinet would, it was thought, encourage greater cross-party consensus behind the war, not to mention hopefully mean that any negative public reaction would rebound on all parties.

Naturally, this last possibility was a concern for Labour and the Conservatives but politicians from those parties eventually came round to the idea that participation in a coalition would allow them to share some of the praise for a successful war and demonstrate that both parties were responsible for government after over a decade of Liberal hegemony. In the end, two politicians from each party entered the cabinet: for the Conservatives, Hugh Cecil became Under Secretary in the Foreign Office and Edward Carson became Solicitor General; for Labour, Ramsay MacDonald became the first Minister for Labour (with a brief that effectively boiled down to keeping the unions on side for the course of the war) and Phillip Snowden was given the newly created position of First Secretary to the Treasury (effectively deputy Chancellor). The performance of these four was well regarded until Lloyd George terminated the coalition on 12 July 1918.

Despite the enormous human cost of the intense fighting in the year in which the UK fought in the war (around 210,000 dead and 229,000 wounded for the Empire as a whole, 142,000 and 150,000 for the UK itself), there was a perverse way in which the way had improved Britain’s global position, further empowering Britain (and by extension the Empire) as a global power to an extent that was perhaps not fully appreciated at the time. The war loans had further entrenched Britain’s position as the globe’s main creditor nation and war orders had enabled British industry to modernise (particularly in the aeronautics and motor sectors) without having to suffer as much of the attendant human cost as the Americans or the French had had to.

On a military and political level, the speed with which the IEF and EEF had had to be mobilised meant that a variety of different units (Canadian, English, Australian, African etc.) had gone into battle alongside one another. Thus, not only had the closing year of the war demonstrated the effectiveness of the Imperial army’s ‘lightning war’ tactics but had gone further to ideologically draw the scattered peoples of the Dominions into a unified imagined community. Figures from the Dominions, such as Australian career-soldier General Monash and the Irish and Maori soldiers who had served heroically alongside each other at the Battle of Trier, became national heroes across the Empire, creating an opportunity for national expression under the general imperial umbrella.

The remainder of Lloyd George’s premiership is not, however, well regarded by historians. He had resisted entrance in the War as part of an effort to insulate his domestic political programme from the political, social and economic dislocations of war but this had proven in vain. In October 1919, the UK entered a sharp deflationary recession which was to last until June 1921. Wholesale prices collapsed by nearly 40% and unemployment rose from 5% to 9%. Automobile production declined by 60% and industrial production as a whole by 30%. In an attempt to control inflation, the Bank of England increased interest rates. The cause of the crisis has generally been placed at the feet of the end of the War, as factories focused on war production either shut down or retooled themselves and the labour market was disrupted by the return of over 1,500,000 people to the civilian workforce. In response, Lloyd George created the Commission on Unemployment, a cross-party committee made up of businessmen, trades union representatives, civil servants, academics and officials from all parties. The Commission recommended the expansion of Britain’s welfare state as well as further tariffs to protect British (by which was meant, in practice, British and Dominion) industry and agriculture from European and American competition. While these policies did eventually bring down unemployment, they took some time to take effect.

The other main focus of the rest of Lloyd George’s premiership was constitutional affairs. Under the terms of the Life Peerages Act 1920, the Crown was given the power to grant a peerage to any man or woman over the age of 21 to sit in the House of the Lords for life. Although technically granted by the Crown via the New Years Honours List, the Birthday Honours List (to mark the monarch’s official birthday), the Dissolution Honours List (to mark the dissolution of a Parliament) and the Resignation Honours List (to mark the resignation of a Prime Minister), appointments were to be proposed by the Honours Committee (made up of civil servants and members of every party). Additionally, the Government of England Act 1921 finally provided England with a level of devolution comparable to the other nations of the UK. Divided into regions called the West Country, the South East, Greater London, East Anglia, the Midlands, Greater Lancashire and Yorkshire & Humber, with capitals in Bristol, Portsmouth, London, Norwich, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds, respectively.

While the economy climbed out of recession towards the end of summer 1921, the Liberal government could not shake off the impression of age and staleness that hung over it. After over 16 years in government, the same people (more or less) were still sitting around the cabinet table and seemed out of ideas, something only compounded by what was perceived as a weak response to the downturn of 1920. The truth was that it was unlikely that any government could have done anything much more to prevent the economic downturn, all is not fair in economics and politics. Nevertheless, Lloyd George decided to dissolve Parliament in October 1921, attempting to make use of the incipient economic recovery to score a quick victory.

Yorkshire & Humber's capital would almost certainly be York not Leeds, Leeds might have the industry but York has the history and an Archbishop. London being a regional capital could mean some slight of hand over the national Capitol ( not a typo ). Maybe Westminster is treated as an enclave, just to legally separate the two.

I may be mistaken, but up to that point, Greater London (or, more precisely, its inner part) was a county, so I think it could have been arranged through some legal fiction - say, City of London as the capital of England, and City of Westminster where the court, the Parliament and the cabinet ministries have their seats, as the capital of the empire.

I may be mistaken, but up to that point, Greater London (or, more precisely, its inner part) was a county, so I think it could have been arranged through some legal fiction - say, City of London as the capital of England, and City of Westminster where the court, the Parliament and the cabinet ministries have their seats, as the capital of the empire.

Yorkshire & Humber's capital would almost certainly be York not Leeds, Leeds might have the industry but York has the history and an Archbishop. London being a regional capital could mean some slight of hand over the national Capitol ( not a typo ). Maybe Westminster is treated as an enclave, just to legally separate the two.

So up to 1890 IOTL what's now London was divided (roughly) between the City, the greater part of Middlesex and bits of Surrey, Essex and Kent. ITTL's Greater London is roughly the same as OTL's ceremonial counties of Greater London and City of London. The decision to make it a separate devolved assembly basically arose from the concern that London as a whole would be 'too big' and would slot uneasily into any of the South East, East Anglia or even the Midlands. I like the idea of the City technically being the capital of London, although I had imagined that the seat of the assembly would be the OTL County Hall, which isn't in the City (although that's hardly important for the narrative). As for the 'federal' capital, I imagined that the City of Westminster would technically be the capital of the whole UK, although for obvious reasons most people would continue to refer to it as London.

The choice of Leeds as a devolved capital represents the idea that the seats of the devolved assemblies was meant to reflect industrial 'modern' England rather than the older towns. Hence also the choices of Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham and Portsmouth rather than Lancaster, Gloucester, Warwick or Chichester. I was also thinking of Bradford, Sheffield or Newcastle as capitals too. Anyway, it's not particularly important, either way, to be honest.

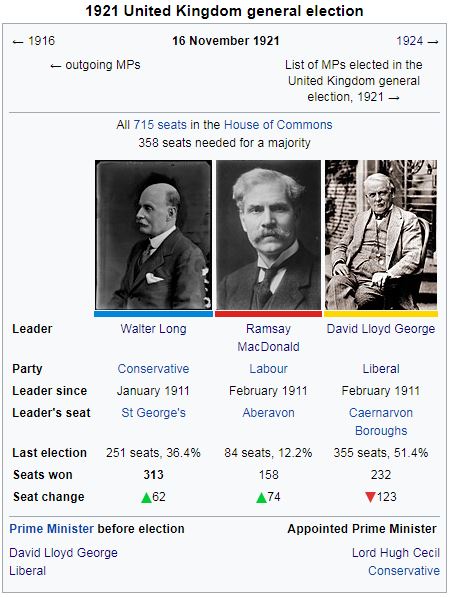

The General Election of 1921

The Orange Order Cometh: The General Election of 1921

Although the 1921 election has since become most well known for the (partial) success of the Conservatives’ Orange Strategy, what was perhaps more notable was what had happened to the Liberal Party. A loss of 123 seats was perhaps not out of the realms of possibility given the recent recession (albeit that it would have been considered a worst case scenario) but the party’s fall to within touching distance of Labour (which gained 74 seats) was a big psychological blow. For a party which had held power for 32 of the past 48 years, it was particularly bitter.

The Conservatives took advantage of their position as the main opposition to the Liberals to scoop up the votes of those dissatisfied with the government, while the Orange Strategy was able to consolidate control over Ulster, Dublin and County Cork. Although the party gained 62 seats, however, many came from areas which were not targeted by the Orange Strategy and which were generally thought to have fallen to the Conservatives as the result of a general dissatisfaction with the Liberals rather than because of any particular popular identification with sectarian anti-Catholicism. Many analysts since then have suggested that the Orange Strategy actually maxed out the vast majority of its support in the 1916 election, and its use by 1921 may even have held down the Conservative vote (something not helped by Craig’s bumbling extremism at the Dublin Assembly in the year since he had taken power).

Labour continued its steady rise with its largest gains yet, gobbling up increasing numbers of seats in the suburbs and other areas outside of its traditional inner city strongholds. Lloyd George’s gambit of forming a coalition in 1917 seems to have notably backfired. Labour was able to use MacDonald’s good performance in government, and his resultant national profile and popularity, as the lynchpin for their campaign. With a personally popular leader, Labour campaigned on a slogan of ‘Ready for Government’ and, for the first time, it looked like they meant that literally.

When the dust settled on 16 November, it was clear that the UK was moving out of an age of majority government. With the Conservatives the largest party but over 40 seats from a majority, many began to talk about the possibility of a progressive coalition between Labour and the Liberals. However, when it became clear that Lloyd George’s head would be the price of any coalition, the Liberal leadership demurred at the idea of the tail wagging the dog. Instead, on the night of 19 November, Austen Chamberlain held a meeting with Hugh Cecil, where they agreed that the Liberals would vote for the Conservatives first budget in December, on the condition that they did not institute radical cuts (at least initially) and that Long, a divisive figure, was pensioned off to the Lords.

Chamberlain was under the impression that he had gained a big concession in these talks, effectively dictating the choice of Prime Minister to the Conservatives. However, this could not be further from the truth. In reality, Long was old and had agreed with Cecil to stand aside in his favour should it come to that. Thus, on 21 November Cecil walked into Number 10 at the head of the first Conservative government (albeit only a minority) for 16 years.

Although the 1921 election has since become most well known for the (partial) success of the Conservatives’ Orange Strategy, what was perhaps more notable was what had happened to the Liberal Party. A loss of 123 seats was perhaps not out of the realms of possibility given the recent recession (albeit that it would have been considered a worst case scenario) but the party’s fall to within touching distance of Labour (which gained 74 seats) was a big psychological blow. For a party which had held power for 32 of the past 48 years, it was particularly bitter.

The Conservatives took advantage of their position as the main opposition to the Liberals to scoop up the votes of those dissatisfied with the government, while the Orange Strategy was able to consolidate control over Ulster, Dublin and County Cork. Although the party gained 62 seats, however, many came from areas which were not targeted by the Orange Strategy and which were generally thought to have fallen to the Conservatives as the result of a general dissatisfaction with the Liberals rather than because of any particular popular identification with sectarian anti-Catholicism. Many analysts since then have suggested that the Orange Strategy actually maxed out the vast majority of its support in the 1916 election, and its use by 1921 may even have held down the Conservative vote (something not helped by Craig’s bumbling extremism at the Dublin Assembly in the year since he had taken power).

Labour continued its steady rise with its largest gains yet, gobbling up increasing numbers of seats in the suburbs and other areas outside of its traditional inner city strongholds. Lloyd George’s gambit of forming a coalition in 1917 seems to have notably backfired. Labour was able to use MacDonald’s good performance in government, and his resultant national profile and popularity, as the lynchpin for their campaign. With a personally popular leader, Labour campaigned on a slogan of ‘Ready for Government’ and, for the first time, it looked like they meant that literally.

When the dust settled on 16 November, it was clear that the UK was moving out of an age of majority government. With the Conservatives the largest party but over 40 seats from a majority, many began to talk about the possibility of a progressive coalition between Labour and the Liberals. However, when it became clear that Lloyd George’s head would be the price of any coalition, the Liberal leadership demurred at the idea of the tail wagging the dog. Instead, on the night of 19 November, Austen Chamberlain held a meeting with Hugh Cecil, where they agreed that the Liberals would vote for the Conservatives first budget in December, on the condition that they did not institute radical cuts (at least initially) and that Long, a divisive figure, was pensioned off to the Lords.

Chamberlain was under the impression that he had gained a big concession in these talks, effectively dictating the choice of Prime Minister to the Conservatives. However, this could not be further from the truth. In reality, Long was old and had agreed with Cecil to stand aside in his favour should it come to that. Thus, on 21 November Cecil walked into Number 10 at the head of the first Conservative government (albeit only a minority) for 16 years.

Last edited:

Cecil Ministry (1921-1924)

Hughliganism in Parliament: Domestic and Constitutional Reform under Lord Cecil

Craig's Birthday Present - a contemporary satirical cartoon shows Carson kidnapping Ulster to give as a present to James Craig

Despite the heat surrounding the Orange Strategy, the biggest thing on Cecil’s agenda when he came to power was that of inter-Entente war debts. To put things simply, Britain was owed money by the United States (which was in turn owed money by France) and Russia. Roosevelt had initially promised Lloyd George that the Americans would collect no more money from the Entente that she was required to repay but this proved hard in the depressed circumstances of the immediate postwar economy. However, on a trip to London, the American Treasury Secretary John M. Parker (fresh from his fateful role as Ambassador to Paris in 1913 - 1919) agreed at a 1922 meeting to repay $40,000,000 per annum to the UK, up from the $25,000,000 that British officials had thought the Americans would agree to.

Since 1917, the British and Bolshevik governments had made a series of (slightly) contradictory agreements regarding the repayment of British loans. Following disagreement at the Paris Conference, the Bolsheviks had flatly repudiated the loans advanced by French banks but Lloyd George’s agreement with Trotsky in 1917 to repay a negotiated amount of the British loans seemed to have survived Trotsky’s fall from grace in 1921. Trotsky’s replacement, Georgy Chicherin, proved similarly pragmatic in his relations with Russia’s former Entente allies and sought good relations with and foreign investment from Britain. The resulting Chicherin Treaty appeared in July 1922 and restored trade relations between the two countries to what they had been in 1913. A sticking point proved to be the 1892 general agreement on tariffs (which was subject to its own simultaneous negotiation with the Dominions), which prevented Britain unilaterally lowering its trade barriers with the Russians. This in turn lead to negotiations turning increasingly bad tempered, with the Russian delegation making repeated threats about repudiating their loans. The resulting document made a fairly vague declaration about further future discussions on the problem of the bondholders. However, the signing of the treaty in July 1922 did mean that the British government agreed to guarantee a further loan to the Bolsheviks.

Despite its subsequent reputation, at the time the Cecil premiership attempted to pursue a moderate course, aware that the public had not trusted a Conservative government for many years and that this present one retained its majority on a case by case basis. One of the more consequential reforms the government undertook was a liberalisation of the divorce laws in 1923. With Stanley Baldwin as Chancellor, the UK economy was recovering steadily from the postwar recession, with the UK entering a period of significant and steady economy growth (although whether this was a direct result of Baldwin's stewardship or merely a temporal coincidence is, of course, up for debate). At the same time, new products such as automobiles, radios and early motion pictures began to become more widely available.

As 1922 turned into 1923, Cecil found himself and his government popular with the electorate and Conservative strategists allowed themselves to contemplate an election at some point in the summer of 1923. However, trouble soon appeared in the form of a crisis in Ireland. Craig’s election as First Minister in 1920 had been a great personal success for the Conservatives but his premiership since then had been nothing short of a disaster. A series of bungled sectarian gestures - including a bizarre scheme to enforce an Anglican Bible and prayer book across the whole island - had created the impression of an incompetent administration more interested in relitigating the religious splits of the seventeenth century than in governing effectively in the twentieth. Within two years, Craig had alienated much of his support outside of Ulster and he knew that electoral annihilation faced his party in 1925 if he did not do something. In 1923, a conclave of Conservative ministers held talks with Craig and agreed to a secret plan to hive off the six predominantly-Protestant counties of Ulster and give them their own devolved legislature separate from Dublin.

Passed into law under the royal prerogative, the Northern Ireland Treaty of 1923 immediately occasioned a storm of controversy. Many criticised the nakedly partisan split, noting that the new ‘Northern Ireland’ didn’t even include all of the historic province of Ulster. The implementation of the Treaty, on 8 January, lead to the whole scheme being derisively known as “Craig’s birthday gift.” As expected, the most vociferous criticism came from Irish politicians, both at Westminster and in Dublin, and the Liberals and Labour Party in Ireland joined together to immediately launch a judicial review of the treaty. The landmark case of R (on the application of the Irish Liberal Party and the Labour Party of Ireland) v First Lord of the Treasury (1924) (most commonly shortened to Dublin v Prime Minister) confirmed a number of things which severely damaged Cecil’s government and set important new precedents in British constitutional law. In the first place, the judges ruled that decisions of the royal prerogative were judicially reviewable to the extent that they related to the purview of either the Westminster Parliament or the devolved assemblies. In the second place, they ruled that, because the powers and purviews of the devolved assemblies had been created by Acts of Parliament, they could only be altered or repealed by an Act of Parliament. The entire Northern Ireland Treaty was thus abrogated and the Belfast Parliament was dead before it had even been born.

Following the delivery of the verdict in Dublin v Prime Minister, Carson (Lord Chancellor since 1921 and the man most associated in Westminster with the whole fiasco) resigned in disgrace and a no confidence motion was immediately tabled in the Commons. With the Baldwin, Foreign Secretary Robert Horne and India Secretary George Curzon also resigning, it was soon clear that Cecil’s government was doomed. Despite a speech made in his personal defence from the opposition benches by Winston Churchill, Cecil overwhelmingly lost the vote and resigned, dissolving Parliament at the same time.

Craig's Birthday Present - a contemporary satirical cartoon shows Carson kidnapping Ulster to give as a present to James Craig

Despite the heat surrounding the Orange Strategy, the biggest thing on Cecil’s agenda when he came to power was that of inter-Entente war debts. To put things simply, Britain was owed money by the United States (which was in turn owed money by France) and Russia. Roosevelt had initially promised Lloyd George that the Americans would collect no more money from the Entente that she was required to repay but this proved hard in the depressed circumstances of the immediate postwar economy. However, on a trip to London, the American Treasury Secretary John M. Parker (fresh from his fateful role as Ambassador to Paris in 1913 - 1919) agreed at a 1922 meeting to repay $40,000,000 per annum to the UK, up from the $25,000,000 that British officials had thought the Americans would agree to.

Since 1917, the British and Bolshevik governments had made a series of (slightly) contradictory agreements regarding the repayment of British loans. Following disagreement at the Paris Conference, the Bolsheviks had flatly repudiated the loans advanced by French banks but Lloyd George’s agreement with Trotsky in 1917 to repay a negotiated amount of the British loans seemed to have survived Trotsky’s fall from grace in 1921. Trotsky’s replacement, Georgy Chicherin, proved similarly pragmatic in his relations with Russia’s former Entente allies and sought good relations with and foreign investment from Britain. The resulting Chicherin Treaty appeared in July 1922 and restored trade relations between the two countries to what they had been in 1913. A sticking point proved to be the 1892 general agreement on tariffs (which was subject to its own simultaneous negotiation with the Dominions), which prevented Britain unilaterally lowering its trade barriers with the Russians. This in turn lead to negotiations turning increasingly bad tempered, with the Russian delegation making repeated threats about repudiating their loans. The resulting document made a fairly vague declaration about further future discussions on the problem of the bondholders. However, the signing of the treaty in July 1922 did mean that the British government agreed to guarantee a further loan to the Bolsheviks.

Despite its subsequent reputation, at the time the Cecil premiership attempted to pursue a moderate course, aware that the public had not trusted a Conservative government for many years and that this present one retained its majority on a case by case basis. One of the more consequential reforms the government undertook was a liberalisation of the divorce laws in 1923. With Stanley Baldwin as Chancellor, the UK economy was recovering steadily from the postwar recession, with the UK entering a period of significant and steady economy growth (although whether this was a direct result of Baldwin's stewardship or merely a temporal coincidence is, of course, up for debate). At the same time, new products such as automobiles, radios and early motion pictures began to become more widely available.

As 1922 turned into 1923, Cecil found himself and his government popular with the electorate and Conservative strategists allowed themselves to contemplate an election at some point in the summer of 1923. However, trouble soon appeared in the form of a crisis in Ireland. Craig’s election as First Minister in 1920 had been a great personal success for the Conservatives but his premiership since then had been nothing short of a disaster. A series of bungled sectarian gestures - including a bizarre scheme to enforce an Anglican Bible and prayer book across the whole island - had created the impression of an incompetent administration more interested in relitigating the religious splits of the seventeenth century than in governing effectively in the twentieth. Within two years, Craig had alienated much of his support outside of Ulster and he knew that electoral annihilation faced his party in 1925 if he did not do something. In 1923, a conclave of Conservative ministers held talks with Craig and agreed to a secret plan to hive off the six predominantly-Protestant counties of Ulster and give them their own devolved legislature separate from Dublin.

Passed into law under the royal prerogative, the Northern Ireland Treaty of 1923 immediately occasioned a storm of controversy. Many criticised the nakedly partisan split, noting that the new ‘Northern Ireland’ didn’t even include all of the historic province of Ulster. The implementation of the Treaty, on 8 January, lead to the whole scheme being derisively known as “Craig’s birthday gift.” As expected, the most vociferous criticism came from Irish politicians, both at Westminster and in Dublin, and the Liberals and Labour Party in Ireland joined together to immediately launch a judicial review of the treaty. The landmark case of R (on the application of the Irish Liberal Party and the Labour Party of Ireland) v First Lord of the Treasury (1924) (most commonly shortened to Dublin v Prime Minister) confirmed a number of things which severely damaged Cecil’s government and set important new precedents in British constitutional law. In the first place, the judges ruled that decisions of the royal prerogative were judicially reviewable to the extent that they related to the purview of either the Westminster Parliament or the devolved assemblies. In the second place, they ruled that, because the powers and purviews of the devolved assemblies had been created by Acts of Parliament, they could only be altered or repealed by an Act of Parliament. The entire Northern Ireland Treaty was thus abrogated and the Belfast Parliament was dead before it had even been born.

Following the delivery of the verdict in Dublin v Prime Minister, Carson (Lord Chancellor since 1921 and the man most associated in Westminster with the whole fiasco) resigned in disgrace and a no confidence motion was immediately tabled in the Commons. With the Baldwin, Foreign Secretary Robert Horne and India Secretary George Curzon also resigning, it was soon clear that Cecil’s government was doomed. Despite a speech made in his personal defence from the opposition benches by Winston Churchill, Cecil overwhelmingly lost the vote and resigned, dissolving Parliament at the same time.

Last edited:

I suspect that the Irish Tories won't do as well in the next Irish election somehow.

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Share: