You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Anglo-Saxon Social Model

- Thread starter Rattigan

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030Craig being that bumbling in an all Ireland context doesn't sit that well. OTL he was under serious internal pressure from Protestant extremists but he was not personally a bigoted man ( the Catholic Unionists Bonaparte Wyse and Denis Henry were lifelong friends of his and he appointed one Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Education and the other NI's first Lord Chief Justice) or more than conventionally religious (the religious unionists at that time actually had huge angst about being led by a whisky distiller) and he was generally regarded as a competent administrator both during the Boer War and the crisis of 1912, WWI and the subsequent Stormont administration (much more so than Carson). He was also a supporter of universal non-sectarian education in NI OTL but got shot down by an unholy alliance of the Orange Order and the Catholic Church. With a sizeable Catholic as well as Protestant support he would have been likely to take a relatively non-sectarian and centrist line.

Craig being that bumbling in an all Ireland context doesn't sit that well. OTL he was under serious internal pressure from Protestant extremists but he was not personally a bigoted man ( the Catholic Unionists Bonaparte Wyse and Denis Henry were lifelong friends of his and he appointed one Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Education and the other NI's first Lord Chief Justice) or more than conventionally religious (the religious unionists at that time actually had huge angst about being led by a whisky distiller) and he was generally regarded as a competent administrator both during the Boer War and the crisis of 1912, WWI and the subsequent Stormont administration (much more so than Carson). He was also a supporter of universal non-sectarian education in NI OTL but got shot down by an unholy alliance of the Orange Order and the Catholic Church. With a sizeable Catholic as well as Protestant support he would have been likely to take a relatively non-sectarian and centrist line.

Craig is probably a bit underserved by this TL, although I have a lower opinion of his personal qualities and talents than you do. It's worth remembering that he was a member of the Orange Order (IIRC) and he bungled his relationship with Westminster over the ending of the Anglo-Irish economic war (albeit that that was a lot later so I suppose we should allow for some disintegration of his abilities). Either way, TTL Craig definitely comes across as more incompetent than his OTL counterpart.

I think that the whole bumbling impression might be because I had to summarise his administration a bit in the interests of saving time. As I imagined it, the nature of Craig's parliamentary coalition meant that he was occasionally required to indulge in a bit of demonstrative sectarianism, of which the prayer book scandal was perhaps the most notable. I had planned to also mention another scandal similar in nature to OTL's 'Cash for Ash' (but it didn't quite fit with sentence structure) which would have demonstrated his government's failure on non-sectarian administrative issues too. So although he could carry moderate Anglo-Irish opinion and some Catholics in 1920, he rapidly lost that because he soon became surrounded by the impression of incompetence and, on the big gestures, he always bent to the worst instincts of the Orange Strategy to keep his base happy. This is then made much worse by the partition scheme. None of this is very sensible, of course, but it's not like the OTL Home Rule and Unionist debates of this period were characterised by sober good sense.

Anyway, not necessarily disagreeing with your points in any major way, just trying to offer a bit of an explanation. Hope that helps.

He was, but you need to look at that in context -so were Terence O'Neill and Brian Faulkner for instance - you didn't get elected a Unionist MP in either Stormont or Westminster without being a member of the Order. Not prior to the 1980s/90s anyway when it began to decline in political influence. It doesn't necessarily reflect a complete adherence to the Order's tenets.It's worth remembering that he was a member of the Orange Order (IIRC)

He was, but you need to look at that in context -so were Terence O'Neill and Brian Faulkner for instance - you didn't get elected a Unionist MP in either Stormont or Westminster without being a member of the Order. Not prior to the 1980s/90s anyway when it began to decline in political influence. It doesn't necessarily reflect a complete adherence to the Order's tenets.

Oh sure, I totally get that it was the cross that you had to genuflect before (so to speak) in order to get anywhere in the UUP...

you didn't get elected a Unionist MP in either Stormont or Westminster without being a member of the Order. Not prior to the 1980s/90s anyway

Serious question (and I don't think it'll be terribly important for this TL), but do you know if Enoch Powell joined the Order when he became a UUP MP?

Last edited:

I absolutely can't think of a better way of putting itit was the cross that you had to genuflect before (so to speak) in order to get anywhere in the UUP

No idea at all I'm afraid, but I don't ever recall seeing him in a sash! He was sui generis though, it was an opportunity for the UUP to capture a nationally known figure and constitutional expert (and, for all I have distaste for some of his views, Powell was a towering intellect)but do you know if Enoch Powell joined the Order when he became a UUP MP

No idea at all I'm afraid, but I don't ever recall seeing him in a sash! He was sui generis though, it was an opportunity for the UUP to capture a nationally known figure and constitutional expert (and, for all I have distaste for some of his views, Powell was a towering intellect)

I looked this up and, according to Wikipedia at least, he was one of only three UUP MPs never to join the Order, which surprises me for some reason (I'm not sure why).

Most probably because he didn't subscribe to some of their core beliefs. He didn't always live up to his ideals, but, by and large, he tried to be consistent and intellectually coherent and (with "Rivers of Blood" as a major, major exception here) principled in his approach.he was one of only three UUP MPs never to join the Order, which surprises me for some reason (I'm not sure why).

The Balfour Declaration, 1922

How Fares the Common-Wealth? The Balfour Declaration and the Curzon-Donoughmore Reforms

The architects of imperial policy under the Conservatives: (l to r) George Curzon, Lord Donoughmore and Arthur Balfour

Aside from its domestic and foreign politics, the Cecil administration had an energetic imperial policy which had a lasting impact on world affairs.

In India, the result of the Ripon Reforms had been to entrench the powers of the Anglo-Indian elite while at the same time opening up certain avenues of advancement to local elite Indians through slight improvements in racial justice and career prospects. However, with the entrance of the UK into the Great War in 1917, plans to further expand the franchise in 1918 ahead of elections to the Chamber of Deputies in 1921 (as had been set out in the Ripon Report of 1893) were shelved. In the context of fighting the war, such concerns as were held by the leaders of the two main Indian nationalist parties (the (notionally) secular Indian National Congress (“INC”) and the Islamic-oriented All-India Muslim League (the “League”)) could be tapped down, at least for a while. However, when it became clear that the plans would be shelved for good over the course of 1920 and 1921, nationalist concern began to rise. In the election campaign of 1921, riots broke out across the subcontinent, as masses of people attempted to break into polling booths and cast the ballots to which they believed they were entitled (the fact that many of them would not have been entitled to vote even if the Ripon Report had been implemented was not something that seemed relevant at the time).

In response, the Viceroy Lord Devonshire cancelled the election results and ordered fresh elections to take place in 1922 under his successor, once it was known who that was. In the repression that followed, over 150,000 members of the INC and the League were arrested and 79 people were killed in scuffles with the Army across the subcontinent. It was in these circumstances that, once Cecil had confirmed his cabinet, the new Viceroy, Lord Donoughmore, and India Secretary, George Curzon, began work on what came to be called the Curzon-Donoughmore Reforms. Hastily conceived, the reforms were designed to accomplish three things at the same time: play the Hindu and Muslim communities off against each other; calm tempers down; and not fundamentally alter the balance of power. They created separate franchises and reserved constituencies for Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims and Europeans and ordered a moderate extension of the franchise (to about half the number of people envisioned by the Ripon Report).

However, when the postponed Indian legislative elections eventually took place in 1922, it was clear that the Reforms had failed in every one of those objectives. Rather than splitting moderate Indian voters from their sectarian nationalist parties, they actually widened the INC’s and the League’s appeal, reducing the Liberal Unionist Party (the governing party since 1893 and the one favoured by the Anglo-Indian community and many upper caste and wealthy Indians) to 76 seats in the assembly, a majority of only 3. Beyond that, individual populations were still frustrated by the moderate extension of the franchise and unionists were concerned about the divisive effects of separate franchises based on religion and ethnicity.

At the same time as the government was grappling with the future of India, they were also confronting the issue of the white Dominions (Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa). As we have seen, the Ottawa agreement on trade and tariffs, which had been in place since 1892, had been stuck to but the feeling in Westminster was that something a bit more formal was needed to replace it. Fortunately for them, the same feeling was afoot in most of the Dominion governments too. Although each Dominion’s government naturally had their own reasons, the effects of the Great War and 30 years of tariff equalization had made the different nations’ economies and cultures almost inseparable, creating a receptive audience for further harmonisation.

The London Conference of 1922 produced a wide-ranging memorandum which is commonly known as the ‘Balfour Declaration’, after the conference’s chairman Arthur Balfour. Although the Balfour Declaration did not commit the UK or the Dominions to any specific legislative programme, it set out a framework for governing the relations of those countries with each other, with the empire and with the wider world.

In the first place, the notion of the ‘British Commonwealth’ was created to describe all the signatories to the declaration. In the Commonwealth, all of the signatories were equal in status, even if the UK remained, de facto, the first amongst equals (it was, for example, up to the Westminster government to grant to any colony the necessary conditions to join the Commonwealth or strip a country of this status). In addition, the Declaration set out the following factors which would determine membership of the Commonwealth (as opposed to the empire more widely) and the relationship between them in the future:

This rudimentary administrative organisation was skeletal and tortured by compromise. The point about staying out of domestic politics was included in order to satisfy the South Africans, whose domestic politics was increasingly dominated by the question of race relations. Furthermore, while a common tariff area was instigated at the insistence of Australian, New Zealand and Newfoundland politicians (largely thanks to agricultural and fishing interests), private promises were made behind the scenes to the Canadian delegation (who were concerned that the tariffs limited their ability to pursue a separate trade policy with the US) that tariffs wouldn’t be increased in the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, it was an important development in intra-Commonwealth relations and was welcomed as such: when it was reported back to the House of Commons, the Liberal leader Austen Chamberlain praised it as the keystone of his father’s imperial vision.

The architects of imperial policy under the Conservatives: (l to r) George Curzon, Lord Donoughmore and Arthur Balfour

Aside from its domestic and foreign politics, the Cecil administration had an energetic imperial policy which had a lasting impact on world affairs.

In India, the result of the Ripon Reforms had been to entrench the powers of the Anglo-Indian elite while at the same time opening up certain avenues of advancement to local elite Indians through slight improvements in racial justice and career prospects. However, with the entrance of the UK into the Great War in 1917, plans to further expand the franchise in 1918 ahead of elections to the Chamber of Deputies in 1921 (as had been set out in the Ripon Report of 1893) were shelved. In the context of fighting the war, such concerns as were held by the leaders of the two main Indian nationalist parties (the (notionally) secular Indian National Congress (“INC”) and the Islamic-oriented All-India Muslim League (the “League”)) could be tapped down, at least for a while. However, when it became clear that the plans would be shelved for good over the course of 1920 and 1921, nationalist concern began to rise. In the election campaign of 1921, riots broke out across the subcontinent, as masses of people attempted to break into polling booths and cast the ballots to which they believed they were entitled (the fact that many of them would not have been entitled to vote even if the Ripon Report had been implemented was not something that seemed relevant at the time).

In response, the Viceroy Lord Devonshire cancelled the election results and ordered fresh elections to take place in 1922 under his successor, once it was known who that was. In the repression that followed, over 150,000 members of the INC and the League were arrested and 79 people were killed in scuffles with the Army across the subcontinent. It was in these circumstances that, once Cecil had confirmed his cabinet, the new Viceroy, Lord Donoughmore, and India Secretary, George Curzon, began work on what came to be called the Curzon-Donoughmore Reforms. Hastily conceived, the reforms were designed to accomplish three things at the same time: play the Hindu and Muslim communities off against each other; calm tempers down; and not fundamentally alter the balance of power. They created separate franchises and reserved constituencies for Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims and Europeans and ordered a moderate extension of the franchise (to about half the number of people envisioned by the Ripon Report).

However, when the postponed Indian legislative elections eventually took place in 1922, it was clear that the Reforms had failed in every one of those objectives. Rather than splitting moderate Indian voters from their sectarian nationalist parties, they actually widened the INC’s and the League’s appeal, reducing the Liberal Unionist Party (the governing party since 1893 and the one favoured by the Anglo-Indian community and many upper caste and wealthy Indians) to 76 seats in the assembly, a majority of only 3. Beyond that, individual populations were still frustrated by the moderate extension of the franchise and unionists were concerned about the divisive effects of separate franchises based on religion and ethnicity.

At the same time as the government was grappling with the future of India, they were also confronting the issue of the white Dominions (Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa). As we have seen, the Ottawa agreement on trade and tariffs, which had been in place since 1892, had been stuck to but the feeling in Westminster was that something a bit more formal was needed to replace it. Fortunately for them, the same feeling was afoot in most of the Dominion governments too. Although each Dominion’s government naturally had their own reasons, the effects of the Great War and 30 years of tariff equalization had made the different nations’ economies and cultures almost inseparable, creating a receptive audience for further harmonisation.

The London Conference of 1922 produced a wide-ranging memorandum which is commonly known as the ‘Balfour Declaration’, after the conference’s chairman Arthur Balfour. Although the Balfour Declaration did not commit the UK or the Dominions to any specific legislative programme, it set out a framework for governing the relations of those countries with each other, with the empire and with the wider world.

In the first place, the notion of the ‘British Commonwealth’ was created to describe all the signatories to the declaration. In the Commonwealth, all of the signatories were equal in status, even if the UK remained, de facto, the first amongst equals (it was, for example, up to the Westminster government to grant to any colony the necessary conditions to join the Commonwealth or strip a country of this status). In addition, the Declaration set out the following factors which would determine membership of the Commonwealth (as opposed to the empire more widely) and the relationship between them in the future:

- The British monarch shall be the constitutional Head of the Commonwealth;

- Free trade should exist between the Dominions and they should have a common set of external tariffs to be decided by annual meetings of relevant politicians and officials;

- There shall be annual meetings of prime ministers and/or their representatives to coordinate inter-Dominion policy; and

- The domestic affairs of a Dominion shall be left undisturbed.

This rudimentary administrative organisation was skeletal and tortured by compromise. The point about staying out of domestic politics was included in order to satisfy the South Africans, whose domestic politics was increasingly dominated by the question of race relations. Furthermore, while a common tariff area was instigated at the insistence of Australian, New Zealand and Newfoundland politicians (largely thanks to agricultural and fishing interests), private promises were made behind the scenes to the Canadian delegation (who were concerned that the tariffs limited their ability to pursue a separate trade policy with the US) that tariffs wouldn’t be increased in the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, it was an important development in intra-Commonwealth relations and was welcomed as such: when it was reported back to the House of Commons, the Liberal leader Austen Chamberlain praised it as the keystone of his father’s imperial vision.

Last edited:

Death of Edward VII (1923)

Death

Almost exactly a year after the creation of the Commonwealth, Edward VII died at the age of 81 after a reign of just over 51 years. On the night of 6 May 1923, he suffered several heart attacks, losing consciousness for the final time at approximately 11:30 at night. His death occasioned a wave of mourning across the Commonwealth, comparable, in a way, to the global celebrations during his Golden Jubilee a year earlier. After a tumultuous reign, the ‘Uncle of the World’ would be greatly missed by his far-flung subjects.

The General Election of 1924

The End of Two-Party Politics? The General Election of 1924

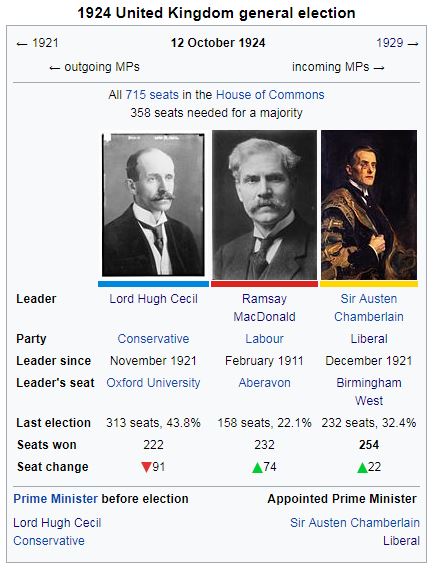

There is no doubt that the Conservatives went into the 1924 election following a humiliating fall from grace. However, when the country went to the polls in October 1924, it did so against the background of a growing economy and a public mood that was, in general, calm (outside of Ireland, at least). Many Labour and Liberal politicians went into the election with the casual assumption that their party was heading towards a landslide but on the campaign trail they soon discovered that the public mood had not turned as decisively against Cecil as the political one had. The one part of the UK where the Conservatives were really doomed was in Ireland outside of Ulster. When the Munster-based peer (and Roman Catholic) the Earl of Kenmare and the Dublin-based businessman and AM* Sir Maurice Dockrell publically defected from the Conservative party when the election was called, it was clear that the southern three provinces of Ireland would be out of the Conservative reach for some time.

An even election in a contentedly divided country produced an evenly divided result in which the three major parties each had between 220 and 260 seats. Although the Conservatives were clearly the biggest losers, losing 91 seats (including all of their seats in Ireland outside of Ulster) and dropping to third place, they were still only 32 seats behind the first-placed Liberals. Labour, indeed, finished in second place for the first time and made the biggest gains of the night, with their carefully crafted appeal leading them to scoop up many of the Irish seats that the Conservatives lost. Nevertheless, with 254 seats the Liberals were technically the winners, even if their overnight gain of 22 seats was considered disappointing and they were still over 100 seats off a majority.

But while much remained murky on the morning of 13 October, what was clear was that Cecil had lost of the confidence of the House and he resigned immediately, advising the King to call for Chamberlain and give him the first opportunity to form a government. Chamberlain, in turn, turned to the Labour Party. He had a great deal of admiration for MacDonald, having found him to be energetic, efficient and astute during his time in the wartime coalition and the two got on well personally. Over dinner at the Reform Club, Chamberlain made MacDonald and offer of a coalition, with Labour MPs entering the cabinet in substantial numbers. MacDonald knew that his party was divided over whether to go into government on anything other than their own terms but he and his closest allies were keen to show that Labour was a responsible party of government and anxious that the opportunity of a formal coalition should not be thrown away for the sake of purity.

Having held secret meetings with union leaders to get them on-side, a vote of Labour MPs showed a result of 225-8 in favour of joining the coalition. As such, Chamberlain became Prime Minister at the head of a Labour-Liberal coalition government. Six Labour MPs joined the cabinet, with MacDonald serving as Lord President of the Council (whose role was beefed up to make it effectively that of deputy Prime Minister), Philip Snowden and John Wheatley were appointed to the newly-created positions of First Secretary to the Treasury and Minister for Housing, respectively. Graham Wallas became Education Secretary, Arthur Henderson became Minister for Labour and Sidney Webb was appointed Colonial Secretary.

* “Assembly Member” - the appellation adopted for all members of devolved assemblies.

There is no doubt that the Conservatives went into the 1924 election following a humiliating fall from grace. However, when the country went to the polls in October 1924, it did so against the background of a growing economy and a public mood that was, in general, calm (outside of Ireland, at least). Many Labour and Liberal politicians went into the election with the casual assumption that their party was heading towards a landslide but on the campaign trail they soon discovered that the public mood had not turned as decisively against Cecil as the political one had. The one part of the UK where the Conservatives were really doomed was in Ireland outside of Ulster. When the Munster-based peer (and Roman Catholic) the Earl of Kenmare and the Dublin-based businessman and AM* Sir Maurice Dockrell publically defected from the Conservative party when the election was called, it was clear that the southern three provinces of Ireland would be out of the Conservative reach for some time.

An even election in a contentedly divided country produced an evenly divided result in which the three major parties each had between 220 and 260 seats. Although the Conservatives were clearly the biggest losers, losing 91 seats (including all of their seats in Ireland outside of Ulster) and dropping to third place, they were still only 32 seats behind the first-placed Liberals. Labour, indeed, finished in second place for the first time and made the biggest gains of the night, with their carefully crafted appeal leading them to scoop up many of the Irish seats that the Conservatives lost. Nevertheless, with 254 seats the Liberals were technically the winners, even if their overnight gain of 22 seats was considered disappointing and they were still over 100 seats off a majority.

But while much remained murky on the morning of 13 October, what was clear was that Cecil had lost of the confidence of the House and he resigned immediately, advising the King to call for Chamberlain and give him the first opportunity to form a government. Chamberlain, in turn, turned to the Labour Party. He had a great deal of admiration for MacDonald, having found him to be energetic, efficient and astute during his time in the wartime coalition and the two got on well personally. Over dinner at the Reform Club, Chamberlain made MacDonald and offer of a coalition, with Labour MPs entering the cabinet in substantial numbers. MacDonald knew that his party was divided over whether to go into government on anything other than their own terms but he and his closest allies were keen to show that Labour was a responsible party of government and anxious that the opportunity of a formal coalition should not be thrown away for the sake of purity.

Having held secret meetings with union leaders to get them on-side, a vote of Labour MPs showed a result of 225-8 in favour of joining the coalition. As such, Chamberlain became Prime Minister at the head of a Labour-Liberal coalition government. Six Labour MPs joined the cabinet, with MacDonald serving as Lord President of the Council (whose role was beefed up to make it effectively that of deputy Prime Minister), Philip Snowden and John Wheatley were appointed to the newly-created positions of First Secretary to the Treasury and Minister for Housing, respectively. Graham Wallas became Education Secretary, Arthur Henderson became Minister for Labour and Sidney Webb was appointed Colonial Secretary.

* “Assembly Member” - the appellation adopted for all members of devolved assemblies.

First-Past-The-Post is only stable with two dominant parties, either somebody introduces election reform or Labour is going to kill one of the other two as a major party, potentially with it being the Conservatives rather than the Liberals ITTL.

They might just join the Liberals and pull it to the right, with Labour being the dominant leftwing party in Ireland outside Ulster.

How long before there's a right-of-centre Irish party to fill the void?

They might just join the Liberals and pull it to the right, with Labour being the dominant leftwing party in Ireland outside Ulster.

How long before there's a right-of-centre Irish party to fill the void?

First-Past-The-Post is only stable with two dominant parties, either somebody introduces election reform or Labour is going to kill one of the other two as a major party, potentially with it being the Conservatives rather than the Liberals ITTL.

They might just join the Liberals and pull it to the right, with Labour being the dominant leftwing party in Ireland outside Ulster.

If there's one thing that history has taught us about democratic politics, it's that parties can often survive even the most embarrassing of setbacks given enough time.

The dynamic for the Liberals is interesting to me (which sounds pretentious now that I say it - given that I wrote it - but bear with me) because I think they probably admire and like the Labour leadership a lot but don't feel that they can follow them too much for fear of losing the ability to leech voters from the Tories (and, bear in mind, a lot of Liberal MPs are still members of or related to the old Whig aristocracy). I think that also works for the other two parties, it's just that the Liberals are caught in the middle: the situation is so finely balanced that they're all scared of moving too far in any direction.

As for the future of FPTP, that's definitely on people's minds but, as things are now, both sides of the Lib-Lab coalition think that they will be able to eat the other at the next election. And, y'know, the general geopolitical dynamics and economic situation isn't all that different from IOTL so maybe other things are going to intervene...

Last edited:

Austen Chamberlain Ministry (1924-1929)

The Roaring Twenties: Social Reform and Economic Progress under the Lib-Labs

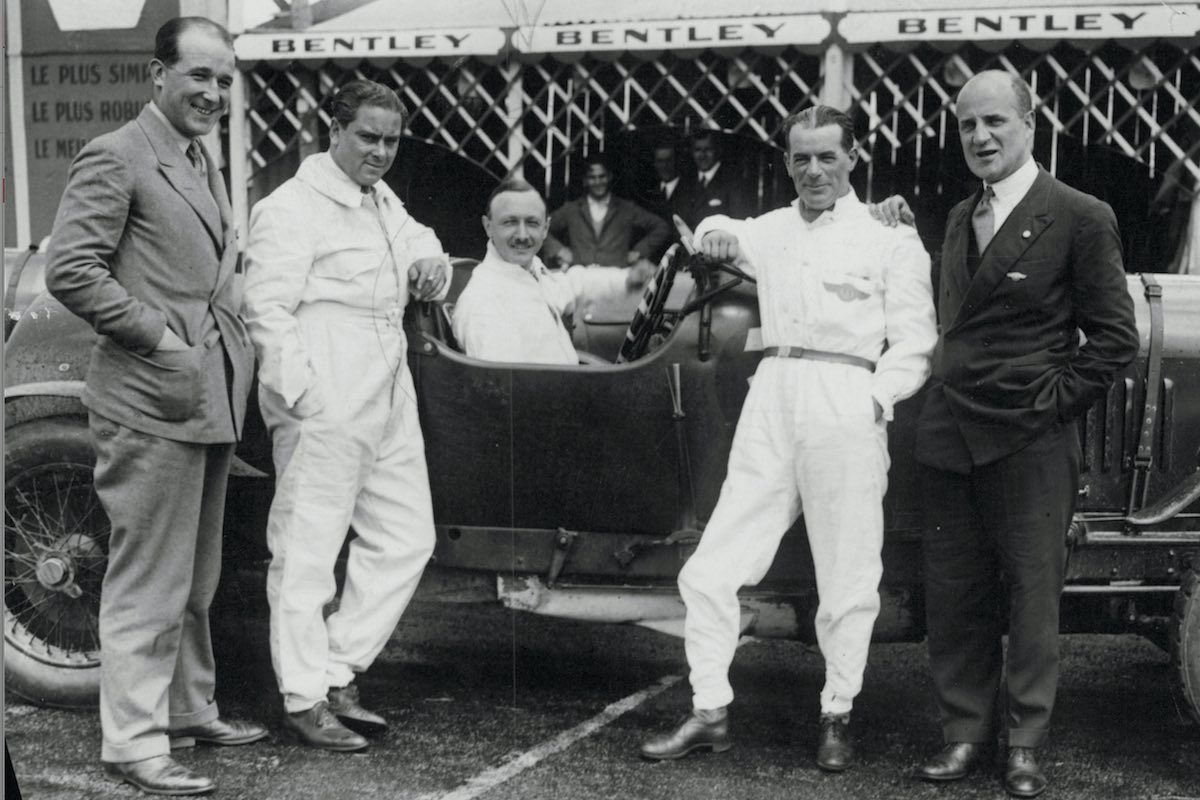

The Bentley Boys: (from left to right) Bernard Rubin (Australian), Woolf Barnato (South African), Tim Birkin, Frank Clement and Dudley Benjafield (all British) became symbols of Commonwealth togetherness and bold new technologies via their participation in motor racing for the Bentley company

In his first speech in the Commons as Prime Minister, Chamberlain called for “a return to normality” after a decade of global war and internal division. In his first budget later that year, the Chancellor John Simon announced a small cut in marginal tax rates while Philip Snowden announced a new suite of business regulations designed to improve efficiency. For the rest of Chamberlain’s premiership, the British economy, and that of the Dominions and the Empire as a whole, experienced rapid growth, which in turn stimulated technological improvements in industries such as automobiles, radio and cinema. There was also a boom in construction, as both towns and cities prospered and expanded. The new electric power industry transformed life and electrification spread quickly around the country.

Elsewhere, the global economy seemed to be heading back towards its pre-war position. Relations with the United States improved after a period of coolness following Britain’s decision not to go to war in 1913. Debt repayments over Great War loans were renegotiated to British advantage and, in return, imperial preference tariffs were lowered for the United States. This resulted in the closer integration of the two countries’ financial systems, with British credit pouring into the US to help finance their economic growth. Despite the United States taking over as the world’s leading industrial power, the Commonwealth as a whole remained the largest economy in the world and general standards of poverty and unemployment remained low. British industries, notably shipping, continued to dominate the world and notable advances were made in the new industries of automobiles and aeronautics.

As coal seams began to run dry over the course of the decade, energy emerged as a key concern of the Westminster government. As various businesses and institutions, notably the navy, began the transition to oil-based engines, this raised issues of security: the vast majority of the oil market came from the United States and newly-discovered fields in the Persian Gulf, which were currently friendly to the Commonwealth but might not always be. In response to this, in 1926 the British Geological Survey found its organisation and funding beefed up under the executive direction of Alfred Harker, with the explicit aim of investigating into the possibility of domestic oil fields in British and Commonwealth territories.

The Lib-Lab coalition was also responsible for a number of liberalising developments in society. Under Neville Chamberlain, the Home Office supported a number of private members bills which rolled back restrictions on abortion and homosexuality (both in 1927). However, a similar bill in 1928 to introduce what came to be known as ‘no fault divorce’ failed in the Commons on a free vote after a full throated opposition campaign mounted by the Anglican, Catholic and Dissenting Churches. Instead, in early 1929 the government issued minor amending legislation equalising the grounds on which men and women could seek divorce. In 1928, Wallas spearheaded legislation which banned the use of corporal punishment in state schools.

The UK remained a world leader in its standards of living and this received another boost with a vast new housing programme initiated by John Wheatley. He passed the Housing Act 1925, which gave local authorities and central governments greater power to clear slums and build affordable municipal housing. In this he was helped by the Greater London First Minister, Labour’s Herbert Morrison, who proved energetic in building streets of new working class housing. In 1926, a system of compulsory medical insurance was introduced, guaranteeing a reasonable standard of medical attention to the poorest in society for the first time.

Despite both parties of the coalition more or less explicitly saying that they planned to cannibalise their partners at the next election, the ministers in the government found that they actually got on rather well, which probably contributed to the arrangement significantly longer than many had predicted in 1924. By the spring of 1928, however, MacDonald was having to deal with increasing complaints from his MPs that they were under-represented in the coalition (despite them making up the entirety of the government’s majority). The Labour membership was also divided over their response to the coalition, with many happy that the party was further proving its responsibility as a party of government while others urged it to push further. After apparently receiving a particularly powerful earful from activists in his local constituency over the course of the 1928 summer recess, Wheatley resigned in September 1928 and Chamberlain and MacDonald informally agreed to a dissolution in the following spring.

The Bentley Boys: (from left to right) Bernard Rubin (Australian), Woolf Barnato (South African), Tim Birkin, Frank Clement and Dudley Benjafield (all British) became symbols of Commonwealth togetherness and bold new technologies via their participation in motor racing for the Bentley company

In his first speech in the Commons as Prime Minister, Chamberlain called for “a return to normality” after a decade of global war and internal division. In his first budget later that year, the Chancellor John Simon announced a small cut in marginal tax rates while Philip Snowden announced a new suite of business regulations designed to improve efficiency. For the rest of Chamberlain’s premiership, the British economy, and that of the Dominions and the Empire as a whole, experienced rapid growth, which in turn stimulated technological improvements in industries such as automobiles, radio and cinema. There was also a boom in construction, as both towns and cities prospered and expanded. The new electric power industry transformed life and electrification spread quickly around the country.

Elsewhere, the global economy seemed to be heading back towards its pre-war position. Relations with the United States improved after a period of coolness following Britain’s decision not to go to war in 1913. Debt repayments over Great War loans were renegotiated to British advantage and, in return, imperial preference tariffs were lowered for the United States. This resulted in the closer integration of the two countries’ financial systems, with British credit pouring into the US to help finance their economic growth. Despite the United States taking over as the world’s leading industrial power, the Commonwealth as a whole remained the largest economy in the world and general standards of poverty and unemployment remained low. British industries, notably shipping, continued to dominate the world and notable advances were made in the new industries of automobiles and aeronautics.

As coal seams began to run dry over the course of the decade, energy emerged as a key concern of the Westminster government. As various businesses and institutions, notably the navy, began the transition to oil-based engines, this raised issues of security: the vast majority of the oil market came from the United States and newly-discovered fields in the Persian Gulf, which were currently friendly to the Commonwealth but might not always be. In response to this, in 1926 the British Geological Survey found its organisation and funding beefed up under the executive direction of Alfred Harker, with the explicit aim of investigating into the possibility of domestic oil fields in British and Commonwealth territories.

The Lib-Lab coalition was also responsible for a number of liberalising developments in society. Under Neville Chamberlain, the Home Office supported a number of private members bills which rolled back restrictions on abortion and homosexuality (both in 1927). However, a similar bill in 1928 to introduce what came to be known as ‘no fault divorce’ failed in the Commons on a free vote after a full throated opposition campaign mounted by the Anglican, Catholic and Dissenting Churches. Instead, in early 1929 the government issued minor amending legislation equalising the grounds on which men and women could seek divorce. In 1928, Wallas spearheaded legislation which banned the use of corporal punishment in state schools.

The UK remained a world leader in its standards of living and this received another boost with a vast new housing programme initiated by John Wheatley. He passed the Housing Act 1925, which gave local authorities and central governments greater power to clear slums and build affordable municipal housing. In this he was helped by the Greater London First Minister, Labour’s Herbert Morrison, who proved energetic in building streets of new working class housing. In 1926, a system of compulsory medical insurance was introduced, guaranteeing a reasonable standard of medical attention to the poorest in society for the first time.

Despite both parties of the coalition more or less explicitly saying that they planned to cannibalise their partners at the next election, the ministers in the government found that they actually got on rather well, which probably contributed to the arrangement significantly longer than many had predicted in 1924. By the spring of 1928, however, MacDonald was having to deal with increasing complaints from his MPs that they were under-represented in the coalition (despite them making up the entirety of the government’s majority). The Labour membership was also divided over their response to the coalition, with many happy that the party was further proving its responsibility as a party of government while others urged it to push further. After apparently receiving a particularly powerful earful from activists in his local constituency over the course of the 1928 summer recess, Wheatley resigned in September 1928 and Chamberlain and MacDonald informally agreed to a dissolution in the following spring.

Last edited:

I know this is a british centered tml and I really like the post about domestic politics (the best part of the tml IMO), but I have to ask if you are gonna cover the post great war conflicts because I cant see the '20s going without a lot of regional wars in Eastern Europe and the balkans.

That is very foresighted!As coal seams began to run dry over the course of the decade, energy emerged as a key concern of the Westminster government [...] with the explicit aim of investigating into the possibility of domestic oil fields in British and Commonwealth territories.

Yay for that! That makes Britain the most liberal and humane place in the world at that time, I believe... Especially the abolition of corporal punishment in schools comes at a time when behavioralist conditioning was at its peak in learning theory, which probably prolonged the practice IOTL. (By the way, are there any changes in pedagogic psychology ITTL from OTL? Pavlov was a Russian; Thorndyke and Watson were Americans - maybe Britain goes a different way here?) According to some people, this would have massive long-term effects on the acceptance of violence, war etc. in society in general. Either way, Britain could become a shining example of humane education. (And an LGBT haven.)The Lib-Lab coalition was also responsible for a number of liberalising developments in society. Under Neville Chamberlain, the Home Office supported a number of private members bills which rolled back restrictions on abortion and homosexuality (both in 1927). However, a similar bill in 1928 to introduce what came to be known as ‘no fault divorce’ failed in the Commons on a free vote after a full throated opposition campaign mounted by the Anglican, Catholic and Dissenting Churches. Instead, in early 1929 the government issued minor amending legislation equalising the grounds on which men and women could seek divorce. In 1928, Wallas spearheaded legislation which banned the use of corporal punishment in state schools.

So, a more continental approach when compared to OTL's NHS. Sounds good. Who pays for it - only the insured, or also their employers (or anybody else)?In 1926, a system of compulsory medical insurance was introduced, guaranteeing a reasonable standard of medical attention to the poorest in society for the first time.

With the liberals already doing a social democrat job, does labour shift left towards outright democratic socialism? Or will the liberals be satisfied with progress and become a party of the status quo, or even of "responsible government", keeping labour busy securing the social democratic gains made?

I'm also interested in seeing how this Britain get on with other left-of-center governments in the world. Will the benefits remain contained to the British Isles similarly to Nordic social democracy? Or will the larger weight of the UK means its model will be spread more widely?

I'm also interested in seeing how this Britain get on with other left-of-center governments in the world. Will the benefits remain contained to the British Isles similarly to Nordic social democracy? Or will the larger weight of the UK means its model will be spread more widely?

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Share: