Chapter 15: A Desert Called War

"The social and political condition of Arizona being little short of general anarchy, and the people being literally destitute of law, order, and protection, the said Territory, from the date hereof, is hereby declared temporarily organized as a military government until such time as Congress may otherwise provide.

I, John R. Baylor, lieutenant-colonel, commanding the Confederate Army in the Territory of Arizona, hereby take possession of said Territory in the name and behalf of the Confederate States of America.

For all purposes herein specified, and until otherwise decreed or provided, the Territory of Arizona shall comprise all that portion of New Mexico lying south of the thirty-fourth parallel of north latitude." - Proclamation to the People of the Territory of Arizona. August 1st 1861

“By the time of the civil war in 1861 the New Mexico territory, despite its small population, was nearly as divided as the rest of the continental United States in a predictable North-South axis. The people of the southern portion of the territory (primarily below the 34th parallel) felt that the territorial government in Santa Fe was too far away to properly address their concerns and grievances. There had been, since 1856, agitation to carve out a separate territory to better manage the southern portion of the region, but due to the already small population of the region being even smaller in the proposed territory, these cries were ignored. The beginning of hostilities at Fort Sumter in April 1861 merely added to these frictions.

The North had withdrawn the scattered garrisons from the region, rendering the settlers defenceless against the outrages of the Apaches who swooped on the settlers with a vengeance, burning, looting and killing. This prompted secession conventions in Tucson and Mesilla in March where the settlers voted to democratically sever their ties with the North and join their future with the Confederate States of America. The people selected and elected provisional officers for the new Confederate Territory. Dr. Lewis Owings of Mesilla was elected Provisional Governor of the Territory, and Granville Henderson Oury of Tucson was elected as Delegate to the Confederate Congress.

All this might have come to naught had it not been for the heroic actions of Texas Indian fighter Col. John Baylor who under the aegis of organizing a “buffalo hunt” called for 1,000 volunteers to join him on a march west into Arizona. Thus organized the newly minted Second Regiment of Texas Mounted Rifles marched to Mesilla. There they confronted the Union garrison under Major Isaac Lynde operating from Fort Fillmore. In a heroic action Baylor’s outnumbered men routed the Union garrison, who by way of parting bombarded a hill where the pro-Confederate residents had turned out to watch the battle. Lynde and his force were furiously pursued by Baylor’s men who rapidly captured the straggling Northern troops forcing Lynde to surrender his men and equipment to Confederate custody.

The Territory of Arizona was established by proclamation soon after…” History of the Arizona Territory, Frederick Steele, University of Texas, Austin, 1911

The proposed Arizona territory, 1860, identical to the one established in 1861

“The Arizona Campaign was prompted more by political concerns rather than any strategic advantage the region offered. Firstly had been the need to secure the pro-Southern peoples of the region for the Confederate cause. The second had come from the deep seated desire of the Southern states to expand Southern imperialism to the Pacific. Partly mesmerized by visions of a Confederacy which could control the gold fields of the West and dreams of expansion for the institution of slavery into the coveted Mexican provinces of Chihuahua, Sonora, and Baja, Jefferson Davis wasted no time in giving his blessing to the man who proposed the campaign, former United States Army Major, Henry H. Sibley.

Sibley, 44, was an 1838 West Point graduate who had enrolled at age 17 and been commissioned a second-lieutenant in the 2nd US Dragoons. He fought against the Seminoles in Florida, participated in the occupation of Texas, and served in the Mexican War. A military tinkerer he created the ‘Sibley Tent’ based on Plains Indian tents, and the design was widely copied by the United and Confederate States. He participated in Bleeding Kansas before being assigned to the Texas frontier, where when hostilities commenced in 1861 he resigned his commission to join the Southern cause. Stocky and wind burnt he was an excellent spinner, but had never held command of a unit before. This was no detriment to his sudden promotion to brigadier general, and with commendable initiative he set off to recruit the new Confederate “Army of New Mexico” which was pulled together in October of 1861, by then it consisted of roughly 2,500 men organized into a brigade strength force of three mounted rifle regiments (plus one battalion) and three artillery batteries:

Army of New Mexico: (Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley Commanding)

4th Texas Mounted Rifles – Col. James Riley

5th Texas Mounted Rifles – Col. Thomas Green

7th Texas Mounted Rifles – Col. William Steele

2nd Texas Mounted Rifles (3 cos.) – Maj. Charles Pyron

Provisional Artillery Battalion – Maj. Trevanion Teel:

Battery, 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles – Lieutenants Joseph H. McGinnis and Jordon H. Bennett

Battery, 4th Texas Mounted Rifles – Lt. John Relly

Battery, 5th Texas Mounted Rifles – Lt. William Wood

Also included in the force tally are attached companies of Arizona Volunteers and militia. All told, when one factors in the independent militia companies and Baylor’s Mounted Rifles, the South had perhaps 3,000 men who had taken up arms for their cause in Arizona.

Facing them were some 5,000 regulars, militia, and volunteers under Col. Edward Canby. Canby, 43, had graduated West Point in 1837, a year behind Sibley. Indiana born, with delicate features, he had fought the Seminole in Florida and seen action in the Mexican War, breveted three times for gallantry to the rank of Lt. Col for his valor at Contrearas, Chururbusco, and Belen Gates. Seeing postings in New York and California he was assigned to New Mexico in 1860 where he led a futile campaign to punish Navajo raiders who had been preying on settlers’ livestock. At the start of the war while he was a Union man his commander, then Col. William Loring, had resigned to join the Southern cause, leaving Canby to fill the vacancy.

Canby, well aware of Baylor’s audacious sweep to the southwest concentrated his forces at two key points, Fort Craig, where he headquartered himself, and Fort Union, under Col. Gabriel Paul. Canby’s position at Fort Craig would allow him to oppose any Confederate crossing of the Rio Grande and prevent them from pushing north into Union territory. His forces were organized thusly:

At Fort Craig: Col. Edward Canby commanding:

5x regiments of New Mexico Volunteer Infantry – Col. Kit Carson commanding (1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry)[1]

11cos 5th, 7th, 10th, US Infantry

6cos 2nd and 3rd US Cavalry

Provisional Artillery Battery – Capt. Alexander McRae (3rd US Cavalry)

Provisional Artillery Battery – Lt. Hall (5th US Infantry)

As well as a number of hastily organized militia regiments stationed at Fort Craig mustered into service as emergency militia.

At Fort Union: Col John Slough commanding

1st Colorado Infantry (1cos attached 2nd Colorado Infantry) – Maj. John Chivington

4th New Mexico Infantry – Col. Gabriel Paul

Battalion 5th US Infantry

Detachment of 1st and 3rd US Cavalry – Maj. Benjamin S. Roberts (3rd US Cavalry)

1st Provisional Artillery Battery – Captain J.F. Ritter

2nd Provisional Artillery Battery – Captain Ira W. Claffin (3rd US Cavalry)

These were all the forces available in New Mexico to defend the Unions hold on the territory.

At the start of February, Sibley took his forces north from Fort Thorn along the Rio Grande marching towards Santa Fe, the territorial capital, and the major stronghold at Fort Union with the intent to capture the Union stores and supplies there to sustain his army and claim the whole of the territory for the Confederacy. On the 19th his forces arrived across the Rio Grande from Fort Craig and established themselves across the river from Canby’s fortifications. Sibley knew he did not have enough provisions to mount a siege of the Union position, and he could not leave such a large force in his rear, so he would then attempt to lure the Union forces out to the field of battle on conditions favorable to him.

On the morning of the 21st Canby was shocked to look out over the ramparts of Fort Craig and see the alarming sight of Confederate wagons kicking up dust as they trundled northward. Canby, now unable to resist the chance to impede the Confederates progress, sent off a mixed force of cavalry, infantry, and artillery to meet the advancing Confederates under Major Roberts. They emplaced themselves at Valverde ford, and thus blocked Sibley’s progress north.

The 2nd Texas under Pyron was the Southern vanguard and when they arrived at the ford he immediately began to skirmish with the Union forces, such was the furiosity of the fighting that the Union found themselves unable to cross the ford to counterattack. Pyron sent for the 4th Texas to reinforce him and as the action became general Sibley himself ventured forth to take command. With the arrival of the 4th Texas and the artillery under Sibley the action became stalemated as the Confederates, despite their sudden numerical advantage, were poorly armed with hunting rifles, muskets, and shotguns.

By late afternoon the 5th Texas under Col. Green arrived alongside the 7th Texas under Major Raguet. At this point Canby had seen the action engage the Confederate troops and ordered all the troops, save a single regiment of New Mexican militia, to march to the ford, bringing the First and Second New Mexican Volunteers as a reserve.

It was here that the dynamic of the battle changed. Sibley, who had alternated between command at the front and trailing with the wagons, was soon felled by sunstroke (although drunkenness has also been provided as a factor in his collapse) and he relinquished command of the force to Green. Colonel John Green, 47, a veteran of the Texan Revolution and the Texan campaign against the Comanche, where he had commanded artillery and mounted volunteers, was a Virginian born Texan who had enlisted upon Texas’s secession and been elected colonel of the 5th Texas. Naturally aggressive he immediately sought out a way to attack the Union on the other side of the ford.

First he organized a lancer charge which was, predictably, driven back with heavy losses in men and horses, and the lancers rearmed themselves with pistols and continued the engagement. A second attempt was made to carry a charge but it too was driven back.

By 4pm Canby decided that the battle could be won decisively, but having seen the repulse of the Confederate frontal charges he attempted to maneuver his forces to strike the Confederate left. To that end he detached Lt. Hall’s battery to the left supported by Karson’s 1st New Mexico. Seeing this, Green ordered Maj. Raguet to assault this new Union position, but the attack was pushed back and Canby, sensing weakness on the Confederate side began maneuvering his forces to make a decisive strike on that front. In doing so though, he drastically weakened his left leaving it open to a Confederate counter attack.

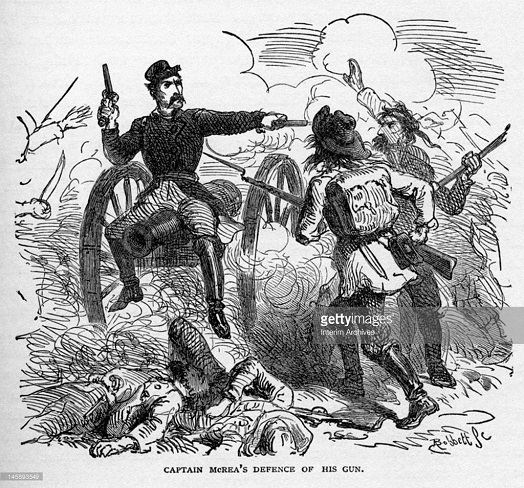

Green sensed this, and, true to his aggressive nature, he organized 700 men in an assault column to strike the unprepared Union right under Maj. S. A. Lockridge of his own 5th Texas. The Confederates were now desperate for water, water which could only be gained by the repulse of their Union foes. So a mad, desperate charge was launched against the Union right. Shockingly this time the charge was not repulsed, and with great skill and determination Lockridge drove hard against the Union lines. The battery facing them was under the command of Capt. Alexander McRae, and though he stood firm at his guns, he, half the gunners, and all the horses, perished in the bitter battle over the Union artillery. Lockridge then turned to the Union forces now out of position crossing the river to assault the Confederate left. This produced a panic amongst the New Mexican Volunteers who were soon put to flight.

The captured Union guns were then turned on the fleeing Union troops. Here, disaster struck. While Canby was struggling to maintain his lines in the face of a sudden determined Confederate assault Karson’s New Mexicans, and the 2nd Colorado Volunteers stood firm to form a rearguard. Lockridge soon turned the guns on this steadfast group and in the ensuing cannonade Canby fell wounded, and the brave Volunteers were driven back in disarray. The rout had become general[2].

In the aftermath the exhausted Confederates could not mount a pursuit in earnest, but harried the New Mexicans all up the river driving many off. Carson would lead his exhausted men back to Fort Craig. The total casualties for the day were steep for the Union, with 71 killed, 160 wounded, and 424 captured or deserted. Amongst that number, was Col. Canby. The Confederate losses were comparatively light, suffering 41 killed and 153 wounded.

At the end of the 21st of February, the Battle of Valverde stood as an astonishing Confederate victory. By the 22nd Sibley had recovered himself, treated his wounded, and was ready to again advance against Fort Craig. Carson, now being the most senior officer in command, requested a truce to treat the wounded and bury the dead. Sibley, compelled by his notion of Southern honor, agreed to a truce lasting until midnight on the 23rd. He used this time to emplace his new captured guns on the high ground above Fort Craig and secure supplies of water from the Rio Grande. Karson, knowing he stood little chance of keeping his now unruly militia in line, buried the dead, disbanded his militia, and on the night of the 23rd quietly slipped out of Fort Craig and marched North, carrying what he could, and discretely destroying as much of the supplies within he could not carry.

So on the morning when the Confederates approached the fort to demand its surrender they found the Union garrison gone. Karson had slipped north with 1,000 men and much of the supplies Sibley had hoped to sustain himself on. Taking what he could and leaving a small garrison in his rear, Sibley marched north, toward Fort Union.” - War in the Southwest: The New Mexico Campaign, Col. Edward Terry (Ret.), USMA, 1966

Despite their valor, the capture of the Union guns spelled disaster for Canby's forces.

-x-x-x-x-

"We are now about to take our leave and kind farewell to our native land, the country that the Great Spirit gave our Fathers, we are on the eve of leaving that country that gave us birth...it is with sorrow we are forced by the white man to quit the scenes of our childhood... we bid farewell to it and all we hold dear." - Charles Hicks, Cherokee Chief, August 4, 1838

“The Indian Territory, at the onset of the American War, was ostensibly set aside as land for the Five Civilized Tribes, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole. These were largely tribes which had been forced from their ancient lands and marched West under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. In this new territory they had adopted different ways of life, many engaging in agriculture, and many in the tribes (particularly the Cherokee and the Chocktaw) practiced slavery.

Long standing distrust of the government in Washington, and concern over the withdrawal of Federal troops led to discussions amongst the chiefs about where to stand in the Civil War. The Confederacy though, immediately saw the advantages of recruiting the tribes to their cause, both in terms of manpower, and for potential expansion after the war. To that end Richmond appointed, attorney and Mexican War veteran Albert Pike to negotiate with representatives of the tribes on behalf of the Confederacy.

Pike managed to negotiate several treaties in early 1861 which earned the alliance of the majority of the Cherokee and the Chocktaw tribes, particularly under the leadership of surprisingly zealous Stand Watie who would command the most ferocious tribesmen who fought for the Confederacy.

Confederate Commissioner to the Five Civilized Tribes, Albert Pike.

The Seminole and Creek peoples though, were split in their support. At the outset of the conflict the Creek and Seminole had their lands sandwiched between the lands of the pro-Confederate Cherokee and the Chocktaw. The Lower Creek peoples, who specialized in cotton production and practiced slavery which put them into closer contact with white settlers, supported the Confederacy thanks to Albert Pike’s treaties which promised them their own state. This led to heightened tensions in the two nations as the two pro-Confederate tribes pressured their neighbors into accepting a pro Confederate stance.

Hampering this, were the loyalties of the Creek Chief Opothleyahola. A distinguished orator and respected elder, Opothleyahola, at 83, had fought the Federal government on numerous occasions during the Seminole Wars, notably after the execution of William McIntosh, a Creek Chief of mixed blood who had signed what the Creek saw as an unfavorable treaty. Thanks to his gifted oratory he was able to negotiate favorable terms with the Federal government in the 1826 Treaty of Washington. However, with the Indian Removal policy in place he soon found himself leading 9,000 of his people from their home land and into the Indian Territory. When the Civil War began, he pledged his own loyalty to the Union, his vast experience teaching him the power of the Federal Government, and he had no desire to see his people again uprooted for the benefit of the white man and warned the Creek nation "My brothers, we Indians are like that island in the middle of the river. The white man comes upon us as a flood. We crumble and fall, even as the sandy banks of that beautiful island in the Chattahoochee. The Great Spirit knows, as you know, that I would stay that flood which comes thus to wear us away, if we could. As well might we try to push back the flood of the river itself.”

Albert Pike met the Creek chiefs and representatives near Eufaula and concluded with them, a treaty of alliance. Opothleyahola leading his delegation of Upper Creeks, bitterly fought this treaty of alliance and urged that neutrality be preserved. The Lower Creek peoples, notably led by Chilly and Daniel McIntosh, sons of the same William McIntosh whom Opothleyahola had killed in 1825, eagerly embraced this treaty however, and both men would go on to organize Confederate regiments in the coming conflict. Seeing his ideal neutrality policy prevented he resigned himself to attempting to sit out the war and with his followers retreated to his plantation on the Canadian River to sit out the conflict.

This would not prove enough though. The McIntosh faction, eager for revenge against the man who had killed their father, soon turned to the Confederate government. Rogue Indian Agent, Confederate Colonel Douglas H. Cooper, had been dispatched by Richmond to take command of the various tribal forces gathering in support of the Confederacy. Daniel McIntosh managed to convince him that Opothleyahola was a potential traitor in their midst. In this they had a legitimate concern, Creeks of black ancestry, fearful of being sold into slavery by the Confederacy had slowly been gathering at Opothleyahola’s plantation. Threats of force from the surrounding tribes and the Lower Creek had forced many more loyalist Upper Creek to seek shelter with their chief and an enormous camp had sprung up there with more than 9,000 people including 2,000 warriors among them. This included a Seminole loyalist band led by Halleck Tustenuggee, the war chief who had fought against the government so hard in the Second Seminole War.

Cooper, agreed with the McIntosh faction and decided he had to move against the loyalist Creek. He soon gathered a force of about 1,400 men under him and marched for the loyalist camp to "drive him and his party from the country." Seeing that the Confederate forces were moving against him Opothleyahola broke camp in November and began moving his people north toward Kansas in order to seek protection for the woman and children amongst his followers.

Cooper though, pursued with a vengeance, spurred on by the McIntosh brothers and their supporters. In late November the two forced met at Round Mountain where the loyalists managed to defeat an assault by their Confederate pursuers and move on. Cooper though, refused to give up the chase, and again closed with the loyalists at Bird Creek, inflicting a loss, but more importantly forcing them to abandon much of their supplies in their retreat. Finally Cooper planned an assault on the loyalists at Chustenahlah, a well-protected cove on Bird Creek with a high hill that dominated the surrounding ground. Here Opothleyahola had dug in his followers, using felled logs as make shift earthworks hoping the bitter winter weather would delay or deter his pursuers.

There would be no such luck. The Confederates mounted a diversionary attack by charging a portion of their force straight up slope, while the remainder worked their way around a shallow defile to the left of the main earthworks. Here they managed to fight their way up through the Creek defenders, and after a few hours of fighting broke into the encampment. The battle turned into a rout as the loyalist Creek fled north, the Confederates, exhausted from the fighting, declined to follow and merely went to looting the abandoned encampment.

The march north was grueling. Approximately 2,000 Creek died of disease, starvation or exposure on their trek. When they finally reached the supposed safety of Fort Row in Kansas, they found it abandoned by the local militia, and were forced to march further north to Fort Belmont. There Kansas militia leader, Capt. Joseph Gunby tried to support the loyalists as much as he could, but supplies quickly dwindled and most of the loyalists had merely the clothes on their backs. Starvation and disease broke out, and a further 1,000 Creek would die, amongst them Opothleyahola’s daughter to cholera in January. Opothleyahola followed soon after, officially of cholera, but according to legend, really of grief at the loss of his beloved daughter.[3]

Come February conditions were desperate, and the mood of the loyalists had turned ugly. They felt abandoned and betrayed by the government, and what few supplies did come for them were mainly cast off goods from the local settlers. Some began agitating to return to their homes and make common cause with the Lower Creek. Principle amongst these agitators was the daughter of Seminole Chief Billy Bowlegs, who had fought hard for the independence of the Seminole people in the Third Seminole War and was the last to be relocated to Indian Territory with his people. Known as Lady Elizabeth Bowlegs for her regal bearing and outspoken nature, she roundly criticized the decision to remain in destitution at Fort Belmont. The Federal government offered them no protection and no succor, why then should they give their loyalty to it? However, she was constantly checked by Halleck Tustenuggee, now de facto leader of the exiled loyalists. He did not believe the Southern cause could triumph and so steadfastly stood by the Union.

The tipping point came in early March 1862 when news of the British outbreak of war arrived in Kansas. This shifted the Creek’s position. With the power of Great Britain now arrayed against the Federal government Tustenuggee’s belief in ultimate Northern victory was badly shaken. Discontent had further grown in the camp as promised supplies failed to arrive and desperation amongst the refugees grew. Finally he sent secret envoys to the Lower Creek explaining the situation amongst the refugees and enquired about the possibility of rejoining the Creek nation. He received promises of good treatment and restored land if he signed a treaty with the Confederate commissioners in Indian Territory. With starvation endemic, and his own leadership being questioned Tustenuggee found he had little choice but to accept the offer.

And so, on March 22nd 1862, Tustenuggee and his followers, all 5,000 of them including 900 warriors, marched south towards Indian Territory. Some 1,200 Creek and Seminole would stay behind, largely those of black ancestry or those with feuds against the Lower Creek. For better or for worse, the fate of the Five Civilized Tribes was now firmly in the hands of the Confederacy.” – Saga of the Five Civilized Tribes, University of California, Berkely, 1979

-----

[1] Really these were separate companies of each regiment organized under overall command of the 1st. Other companies were garrisoning posts around the territory and so only the 1st was at full strength.

[2] I should point out that up until this point everything about the battle is basically the same as OTL. Here chance just falls slightly differently and Canby falls wounded leading to the more disastrous outcome.

[3] Again pretty much OTL until Opothleyahola’s early death.