«Si mis soldados se pusieran a pensar, no quedaría ninguno en las filas.».

«If my soldiers began to think, not one would remain in the ranks..».

— Attributed to Frederick II der Große of Prussia.

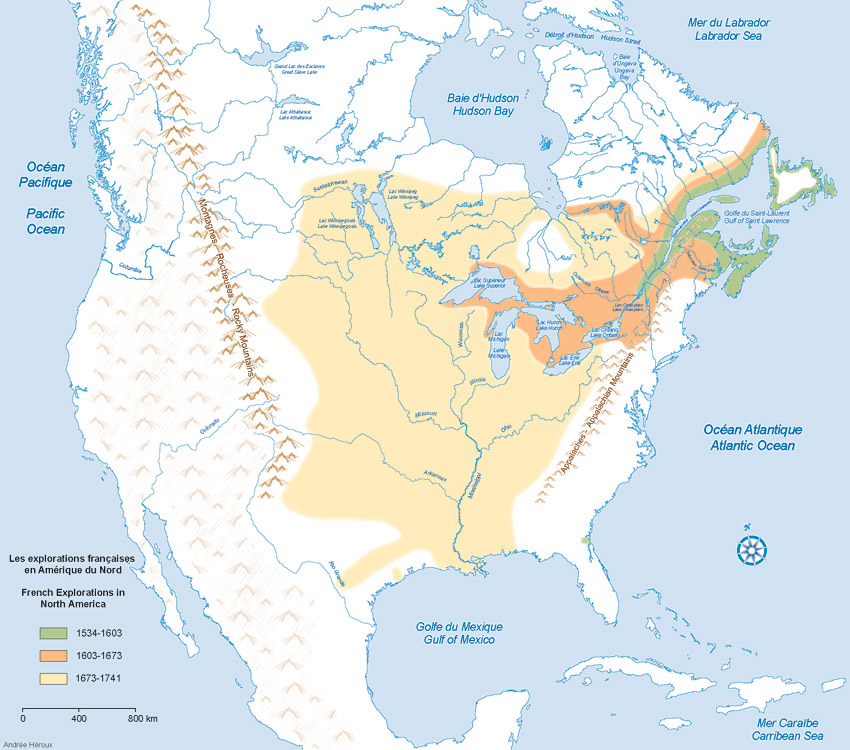

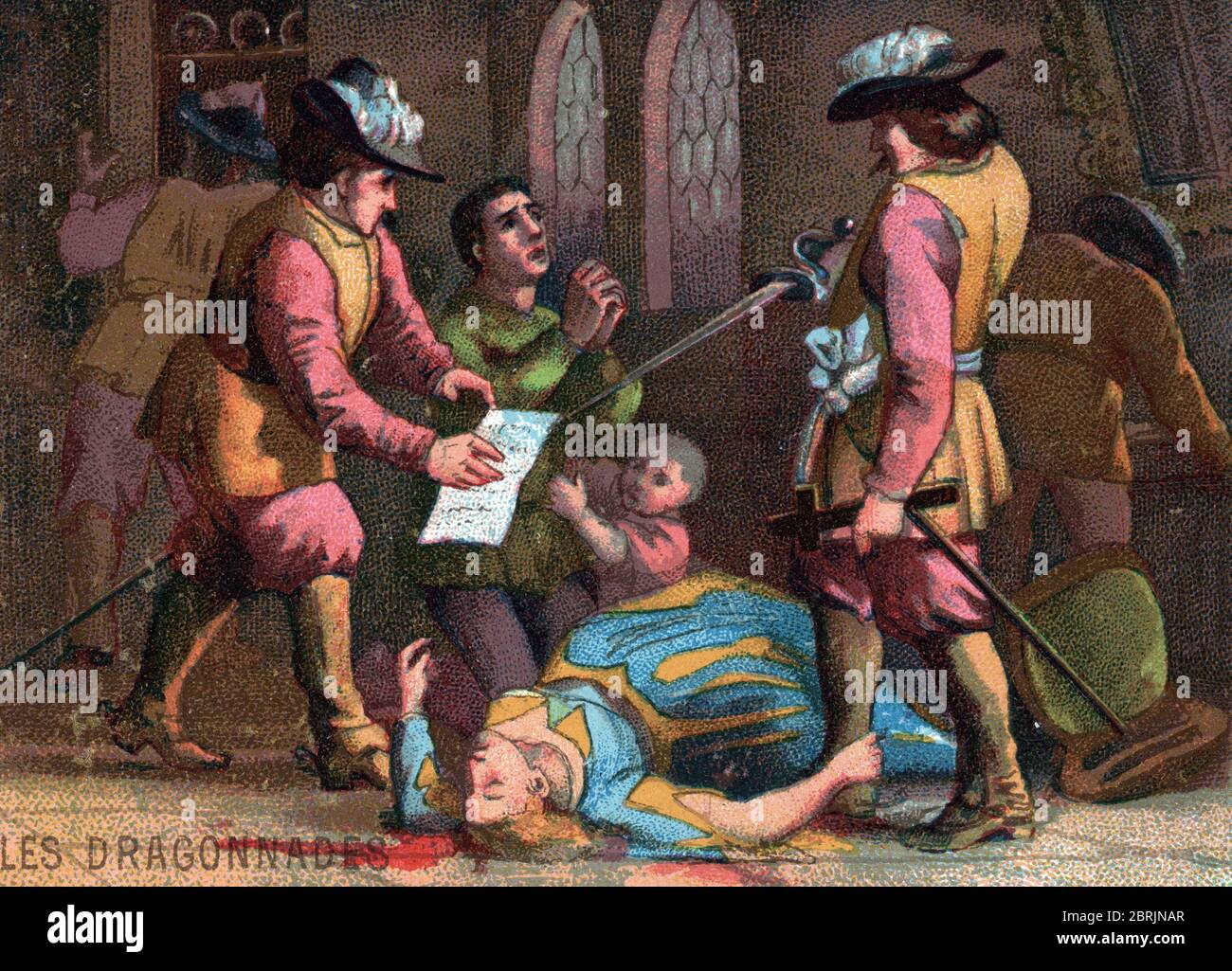

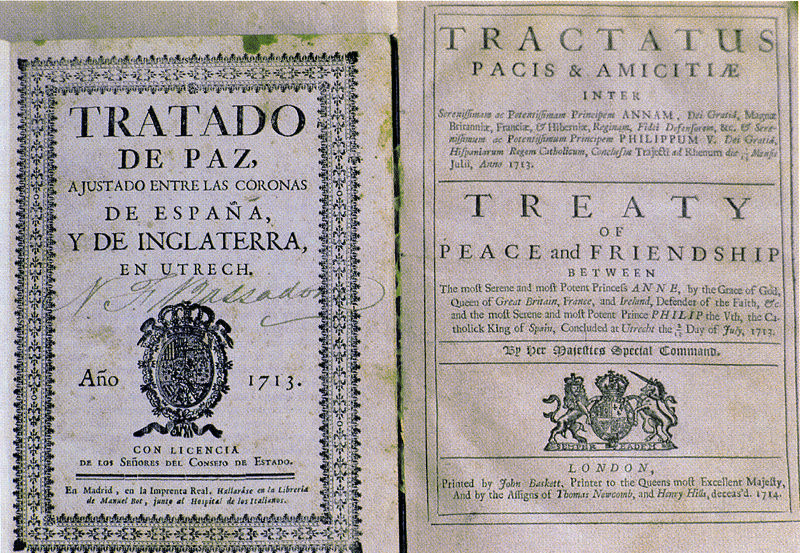

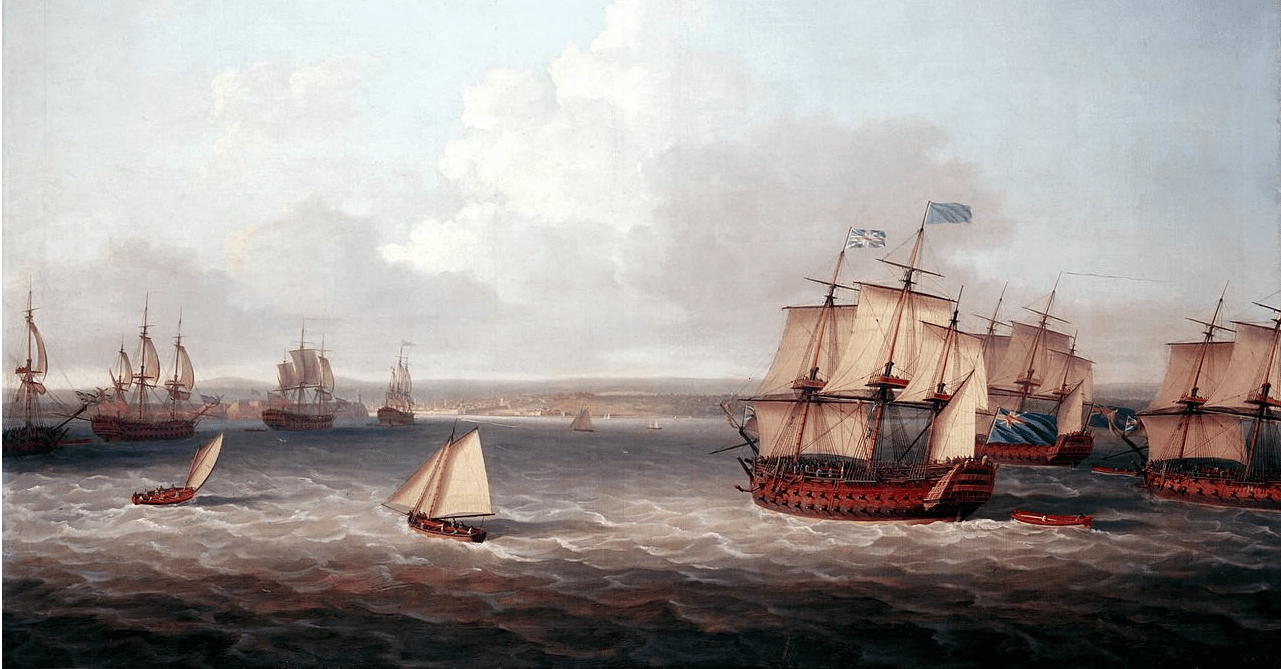

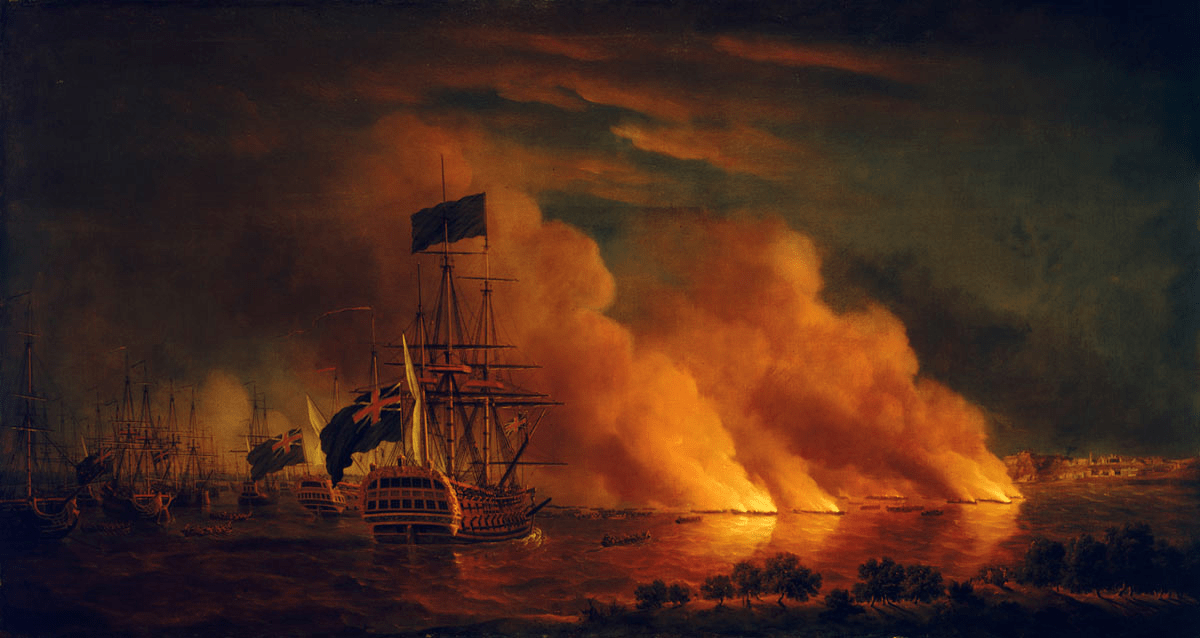

The increase in Anglo-French hostilities in America served as an elevator for the tensions that existed since the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) that put an end to the War of the Austrian Succession, in which Frederick "The Great" Prussia was satisfied and wished for peace, declaring "from now on I will not attack a cat, except to defend myself". Although Prussia was satisfied with the Treaty (it had increased her domains by a million new subjects and 24,000 square kilometers), Austria resented it, enacting sweeping reforms and changing its traditional diplomatic policy to prepare for a renewed war with Prussia. Although France and Great Britain recognized Prussian sovereignty in Silesia under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Austria ultimately refused to ratify the agreement. Maria Theresa, and her husband the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, through State Chancellor Prince von Kaunitz, began talks with her former enemy France; with a view to obtaining aid in the reconquest of Silesia, in exchange for which, she would be offered the Austrian Netherlands. In 1746, Maria Theresa formed a defensive agreement with Elizabeth known as the Treaty of the Two Empresses, which aligned Austria and Russia against Prussia. A secret clause guaranteed Russian support for Austrian claims in Silesia. In 1750 Great Britain joined the anti-Prussian pact; in return, the British expected Austrian and Russian defense in the event of a Prussian attack on the Electorate of Hanover, which King George also ruled in personal union. At the same time, however, Maria Theresa, who had been disappointed with Britain's performance as her ally in the War of the Austrian Succession; he followed the controversial advice of her chancellor Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz that he pursued warmer relations with Austria's old rival, the kingdom of France.

Britain raised tensions in 1755 by offering to finance Russian military deployments in exchange for a Russian army ready to attack Prussia's eastern frontier. Alarmed by this encirclement, Frederick began to work to separate Britain from the Austrian coalition by alleviating King George's concern for Hanover. On January 16, 1756, Prussia and Great Britain agreed to the Westminster Convention, between Frederick the Great of Prussia and King George II of Great Britain, Elector of Hanover. British fears of a French attack on Hanover were responsible for the development of the treaty. Under the terms of the agreement, both Prussia and Great Britain would try to prevent the forces of any other foreign power from passing through the Holy Roman Empire; under which Prussia agreed to guarantee Hanover against French attack, in return for Britain's withdrawal of its offer of military subsidies to Russia. This move created a new Anglo-Prussian alliance and outraged the French court. Austria then sought warmer relations with France to ensure that the French did not take the Prussian side in a future conflict over Silesia. King Louis XV responded to Prussia's realignment with Britain by accepting Maria Theresa's invitation to a new Franco-Austrian alliance. Madame de Pampadour, who at that time exercised royal diplomacy in the French court, and whom Frederick of Prussia had offended by calling her "

Madamoiselle Poisson", because apparently her mother had been a fishmonger, immediately agreed, formalizing the First Treaty of Versailles in May 1756. It was apparently defensive, but British agents suspected that there were secret clauses that were broader than the document actually published. This series of political maneuvers became known as the Diplomatic Revolution. Russia, equally upset by Britain's withdrawal of promised subsidies, reached out to Austria and France, agreeing to a more openly offensive anti-Prussian coalition in April 1756. When France turned against Prussia and Russia broke away from Britain, Kaunitz's plan evolved into a grand anti-Prussian alliance between Austria, Russia, various minor German powers, and France. It was a coalition of 70 million inhabitants against the 4.5 million of Prussia.

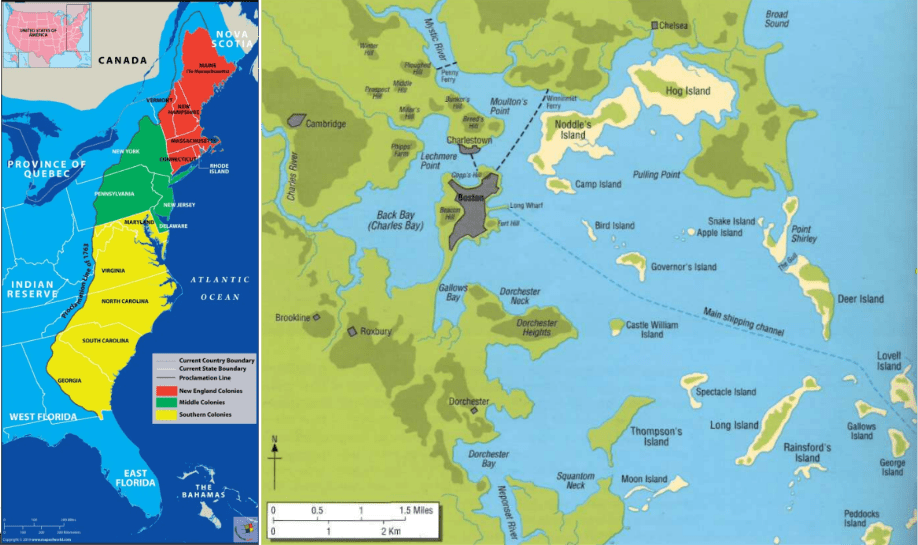

In the summer of 1756, Europe was divided into two sides:

- Austria, the Russian Empire, France, Spain, Saxony, Sweden, and several other small German states.

- Prussia, the United Kingdom, Hannover and other German states.

As Austria and Russia prepared for renewed war, King Frederick became convinced that Prussia would be attacked early in 1757. His spies had reported the preparations in Austria and Russia, and he realized that waiting until they were ready would be fatal. for Prussia. Frederick decided to act preemptively, beginning with an attack on the neighboring Electorate of Saxony, which he correctly believed to be a secret supporter of the coalition against him. Frederick said "after all, it is of little importance whether my enemies call me an aggressor or not, since all of Europe is in league against me." Although Prussia's geographical position allowed Frederick to operate on interior lines, which, considering the circumstances, was an enormous advantage; the country had no defensive frontiers, and in the event of having to face the alliance, its army would be outnumbered 3 to 1. In the south, where the Austrians had joined the Saxons, they were 80 km from Berlin; in the north the Swedes, once concentrated in Stralsund, would be 200 km away; in the east, when the Russians had crossed the Oder River, it would be 75 km; in the west, the French, having entered Prussian territory near Halle, would find themselves 150 km from Berlin. However, there was one favorable factor, and that was that all the armies were in various states of readiness; the Austrian had not met the Saxon; the Russian had to cross the trackless plains of Poland; the Swedes had to cross the Baltic Sea, and the French had to cross the Rhine River.

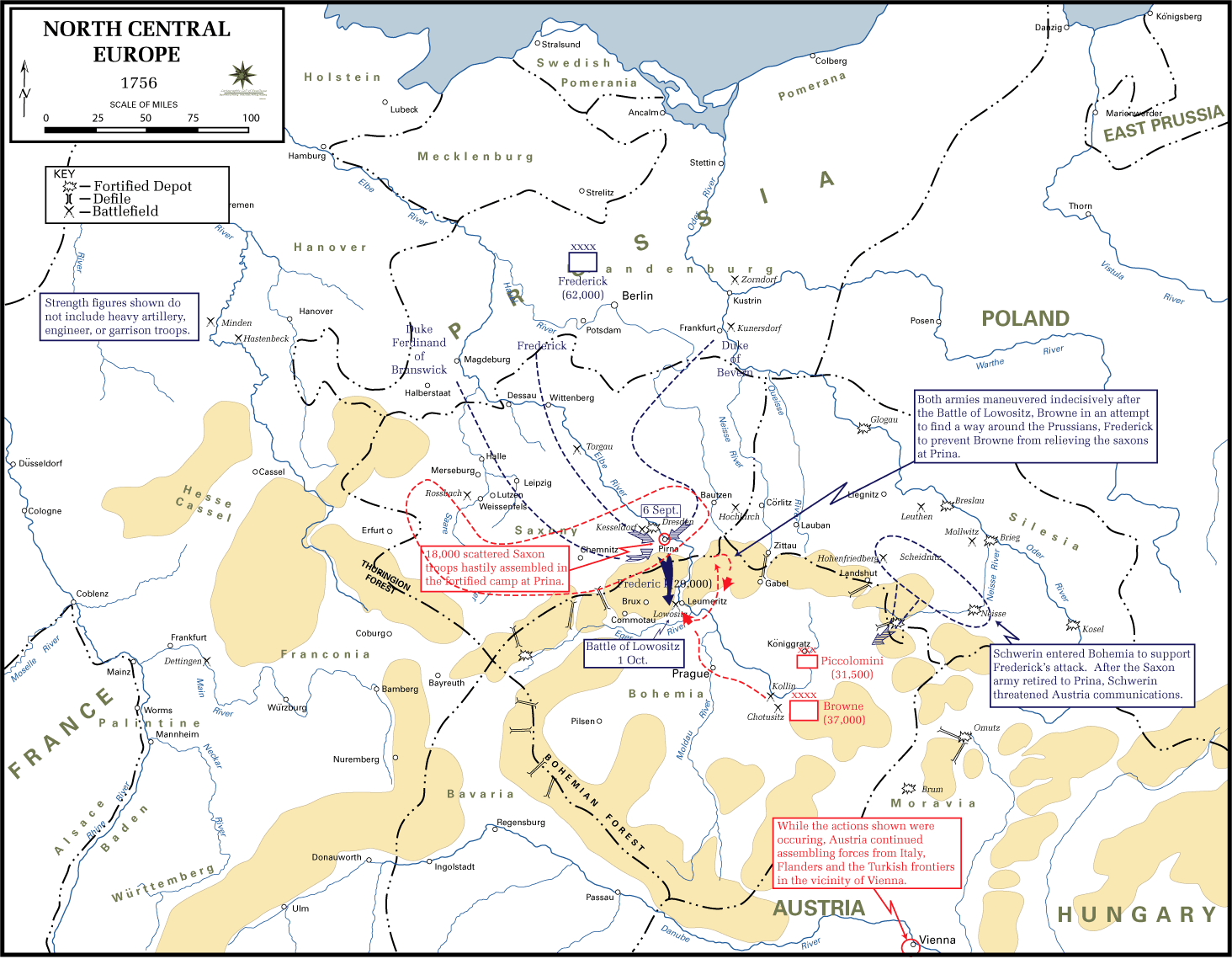

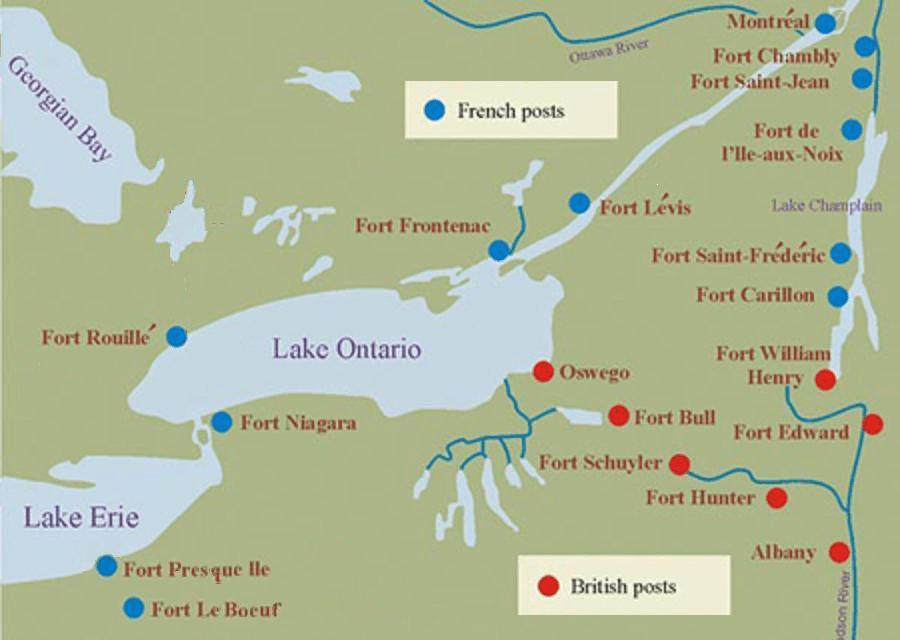

In July, Frederick demanded a guarantee from Vienna that Austrian troop concentrations in Bohemia would not go against Prussia, but received an ambiguous response. Without waiting any longer, Frederick divided the Prussian army into three parts. He put a force of 20,000 under Field Marshal Hans von Lehwaldt in East Prussia to guard against any Russian invasion from the east, with a reserve of 8,000 stationed in Far Pomerania; Russia should have been able to exert irresistible force against East Prussia, but the King relied on the slowness and disorganization of the Russian army to defend his northeastern flank. He also stationed Field Marshal Count Kurt von Schwerin in Silesia with 25,000 men to deter raids from Moravia and Hungary. Ultimately, he personally led the 58,000-strong main Prussian army into Saxony. Prussian troops crossed the Saxon border on August 29, 1756, starting the Third Silesian War. The war would lead to a series of sub-wars, which could be said to be a world war:

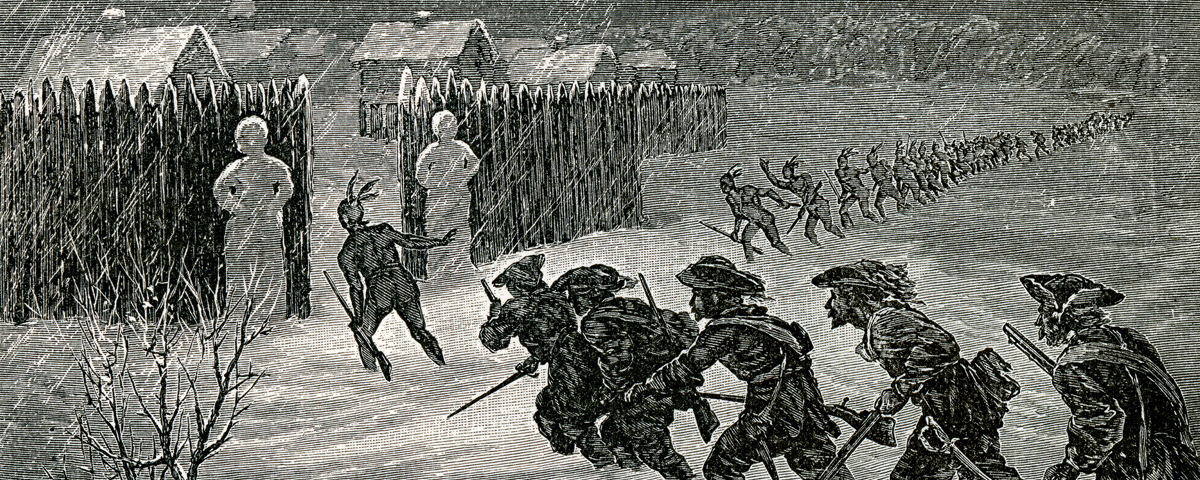

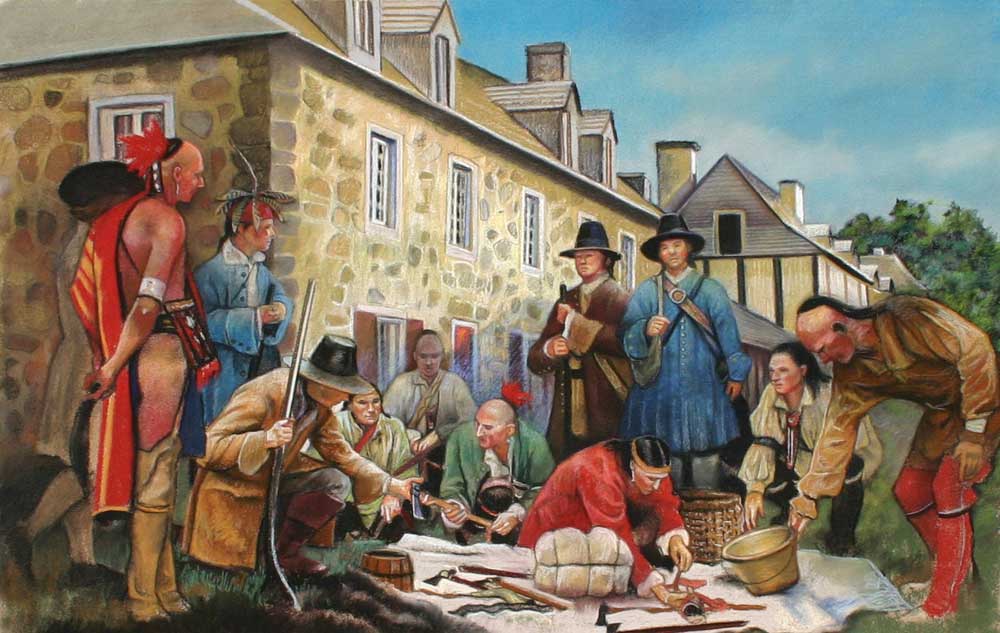

- Franco-Indian War, between the French and English colonies with the participation of Indian tribes.

- Third Silesian War, between Prussia and Austria for control of Silesia.

- The Irish War, between England and Ireland.

- Third Carnatic War, between the English and French colonies in India.

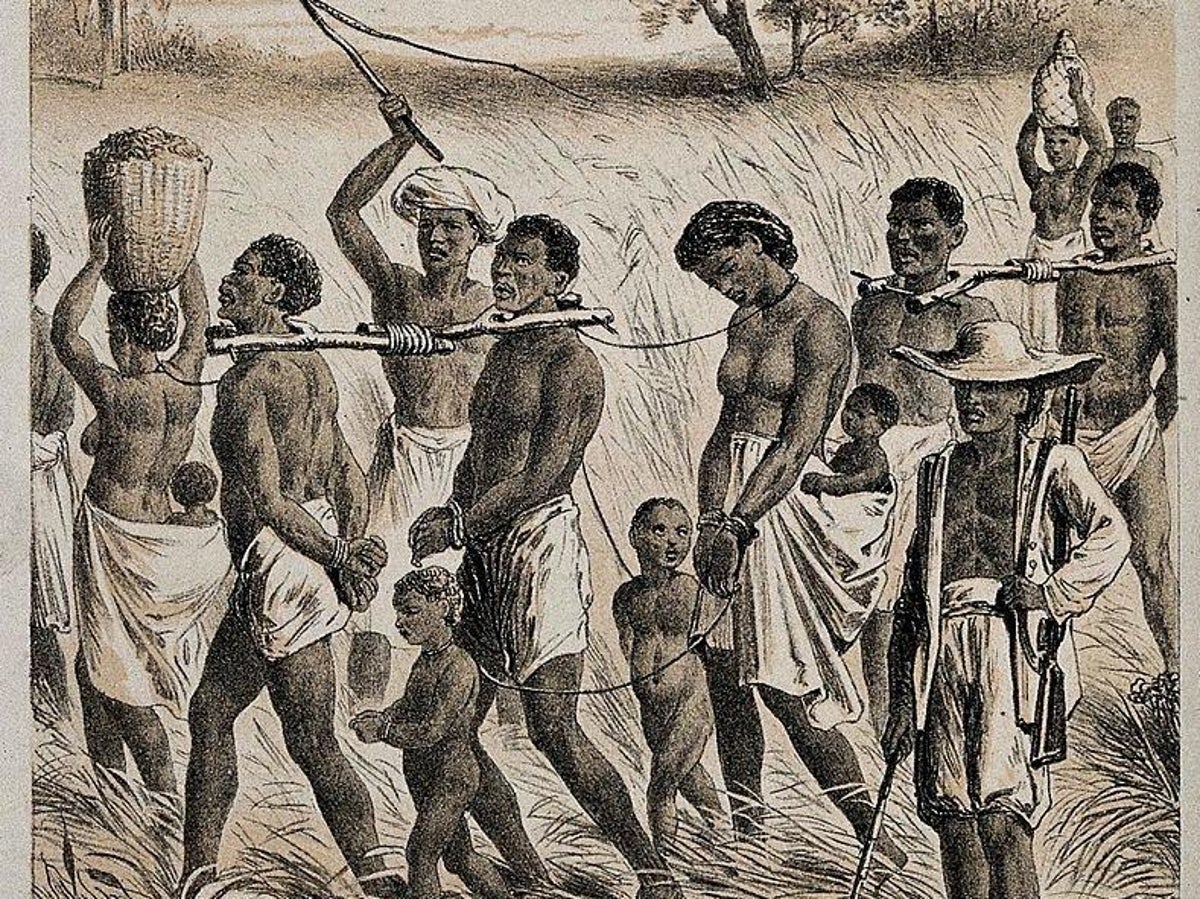

- Anglo-Spanish War, between Spain and England, in the Caribbean, the Philippines and South America.

As Austria and Russia prepared for renewed war, King Frederick became convinced that Prussia would be attacked early in 1757. His spies had reported the preparations in Austria and Russia, and he realized that waiting until they were ready would be fatal. for Prussia. Frederick decided to act preemptively, beginning with an attack on the neighboring Electorate of Saxony, which he correctly believed to be a secret supporter of the coalition against him. Frederick said "after all, it is of little importance whether my enemies call me an aggressor or not, since all of Europe is in league against me." Although Prussia's geographical position allowed Frederick to operate on interior lines, which, considering the circumstances, was an enormous advantage; the country had no defensive frontiers, and in the event of having to face the alliance, its army would be outnumbered 3 to 1. In the south, where the Austrians had joined the Saxons, they were 80 km from Berlin; in the north the Swedes, once concentrated in Stralsund, would be 200 km away; in the east, when the Russians had crossed the Oder River, it would be 75 km; in the west, the French, having entered Prussian territory near Halle, would find themselves 150 km from Berlin. However, there was one favorable factor, and that was that all the armies were in various states of readiness; the Austrian had not met the Saxon; the Russian had to cross the trackless plains of Poland; the Swedes had to cross the Baltic Sea, and the French had to cross the Rhine River. Frederick's broad strategy had three phases.

First, he intended to occupy Saxony, gaining strategic depth and using the Saxon army and money to bolster the Prussian war effort.

Second, he would advance from Saxony into Bohemia, where he could establish winter quarters at Austrian expense.

Third, he would invade Moravia from Silesia, taking the fortress at Olmütz, and advance on Vienna to force an end to the war.

He hoped to receive financial support from the British, who had also promised to send a naval squadron to the Baltic Sea to deter invasion of the Prussian coast, if necessary. In July, Frederick demanded a guarantee from Vienna that Austrian troop concentrations in Bohemia would not go against Prussia, but he received an ambiguous reply. Without waiting any longer, Frederick divided the Prussian army into three parts. He put a force of 20,000 under Field Marshal Hans von Lehwaldt in East Prussia to guard against any Russian invasion from the east, with a reserve of 8,000 stationed in Far Pomerania; Russia should have been able to exert irresistible force against East Prussia, but the King relied on the slowness and disorganization of the Russian army to defend his northeastern flank. He also stationed Field Marshal Count Kurt von Schwerin in Silesia with 25,000 men to deter raids from Moravia and Hungary. Ultimately, he personally led the 62,000-strong main Prussian army into Saxony. In mid-August 1756, Prussian units totaling 62,000 men were moving to assembly points along the Saxon border. These meeting points were:

Halle and Aschersleben for the right column with about 15,000 men, under the command of Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, on the way to Leipzig.

Near Magdeburg and south of Potsdam in Beelitz, Saarmund, Zoffen and Königs-Wusterhausen for the central column withunder King Frederick II on the way to Wittenberg and Torgau .

Cöpenick, Müllrose and Bunzlau for the left column under the Duke of Brunswick-Bevern on the way to Bautzen in Lusatia.

Frederick conferred the main command in Prussia on Field Marshal Lehwaldt and that of Silesia on Field Marshal Schwerin before the start of the campaign. Prussian troops crossed the Saxon border on August 29, 1756, starting the Third Silesian War. The Prussians advanced unopposed until at Wilsdruff, Frederick learned of the Saxon army's retreat towards Pirna, a very strong natural fortress. There the Saxon army (14,599 infantry and 3,665 cavalry) had completed its retreat, carrying provisions (flour and fodder) for 20 days. Frederick of Prussia informed Frederick Augustus II, the Elector of Saxony, that he only intended to march through his country to Bohemia. However, his behavior was more in keeping with an invader. On September 10, much of the Prussian army marched in order to the Saxon camp at Pirna and headquarters were located at Gross-Sedlitz. Meanwhile, Duke Ferdinand's column camped at Cotta; Bevern camped on the heights of Doberzeit. In addition, a cuirassier regiment and three dragoons marched through Dresden to Wilsdruff's camp, where a corps of 16,000 men still remained. On the same day, the Saxon generals, entrenched at Pirna, held a council of war where they considered whether they should hold their ground at Pirna or enter into negotiations with Frederick in order to be considered neutral in this conflict. However, Brühl received a letter from Austrian Field Marshal Browne informing him that Wied was advancing on Aussig and that he would send 800 grenadiers and 20 cavalry to Peterswalde to keep the line of communication open with the Saxon army. The Saxon army had enough provisions to hold until September 26, or until September 30 if provisions were rationed. Taking into account local resources, it was estimated that the army could be supplied until October 12.

Arriving at Gross-Sedlitz, Frederick reconnoitered the area. The Saxons had a first line of defense along the rushing Gottleuba Creek. A second line of defense ran along a stream from Langenhennersdorf to Königstein, apart from which numerous defenses including several infantry battalions along the palisades defended all the passes. Frederick considered the positions too strong to be assaulted and decided to blockade the Saxon army, hoping to starve the defenders out. He deployed his own division from his headquarters at Gross-Sedlitz to Zehista, his second division from Zehista to Cotta and onwards to Hellendorf on the way to Prague. He also established batteries and detachments north of the Elbe, and a pontoon bridge at Schandau. A very strong Prussian Infantry Battalion blocked the bridge from Pirna to stop any possible retreat from this point. The blockade required about 30,000 men. At the time, the Saxon prime minister, Heinrich Count Brühl, and the court still rejected any open cooperation with Browne's Austrian army. They did not want to provoke Federico and followed a policy of appeasement. While the Saxon army remained in the Pirna camp. At dawn on September 13, Duke Ferdinand, accompanying Keith, left his camp with Keith's body and headed for Bohemia to cover the Pirna blockade. In mid-September the Elector of Saxony's headquarters was at Struppen, in the center of the Saxon lines. His army had been on short rations since September 3. In fact, with the Prussians blocking the Elbe River and all the roads, no supplies could reach his camp or either of his two fortresses. The Elector repeatedly asked Austria and France for help. Field Marshal Maximilian Ulysses Browne was hastily preparing his Austrian army at Kolin. Empress Maria Theresa personally contributed some of her own horses to Browne's artillery, which already numbered some 60,000 men.

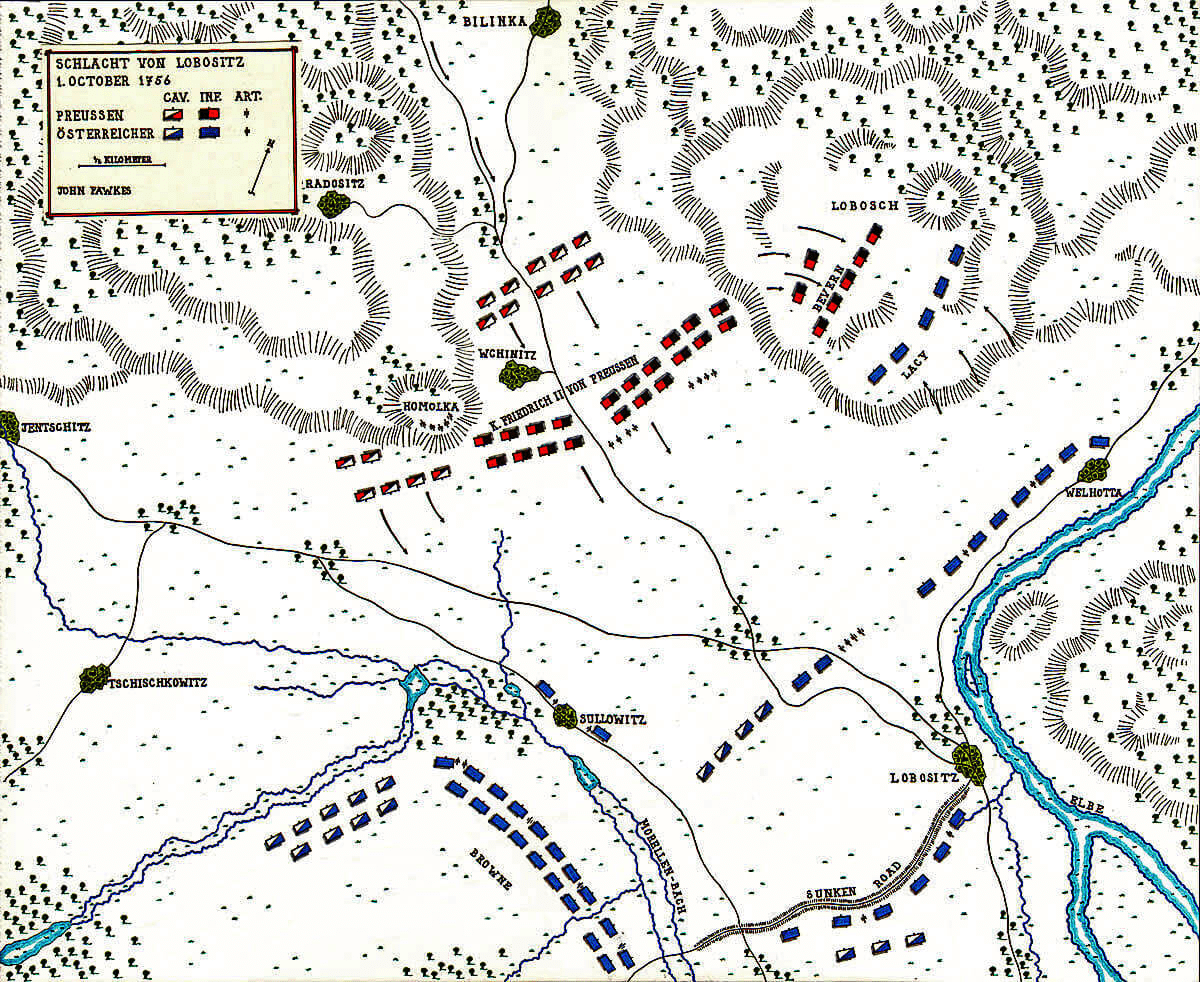

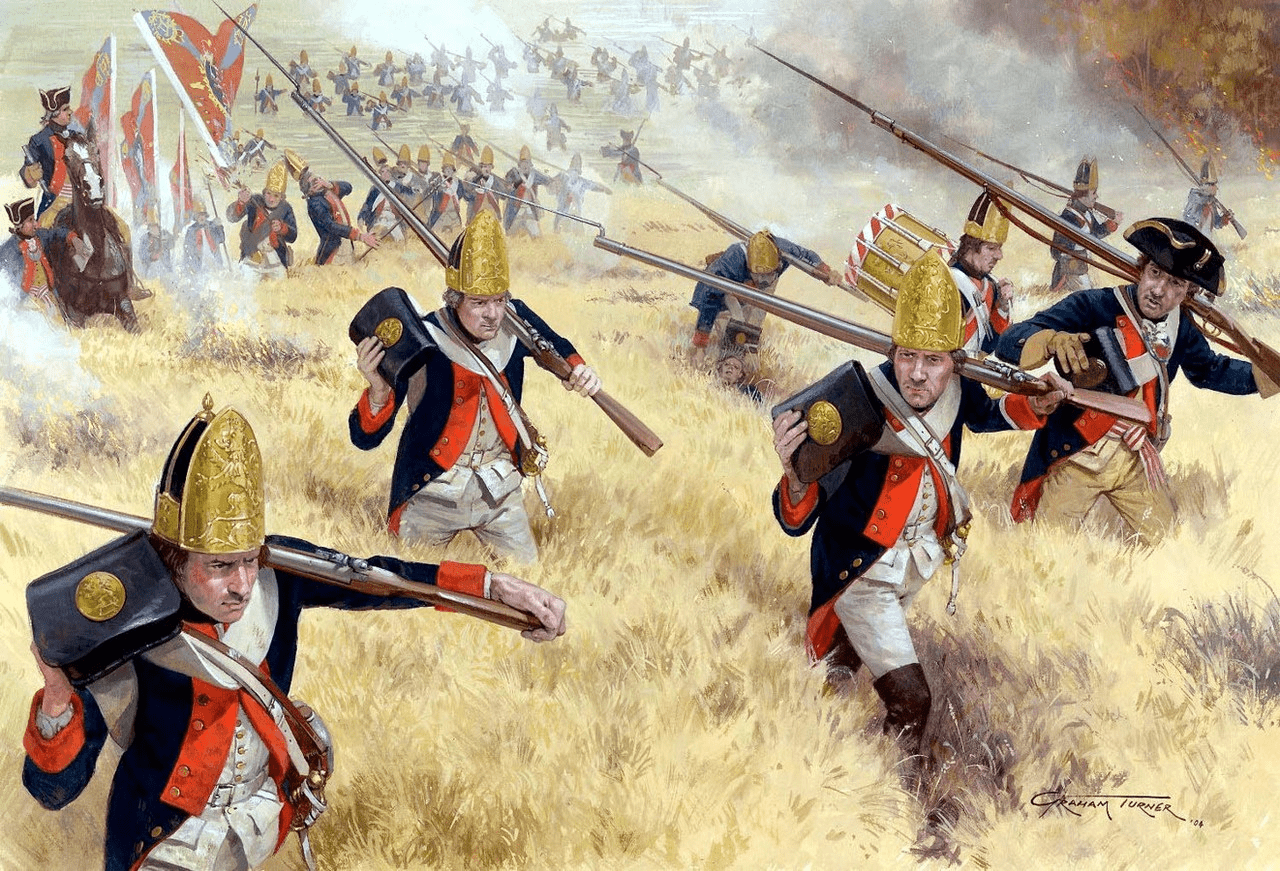

On September 14, Browne marched from Kolin with his infantry towards Budin. On the same day, 180 ships carrying provisions for the Prussian army arrived from Torgau to Dresden, escorted by grenadiers. Ferdinand meanwhile remained in his camp at Peterswalde where he received some pontoons sent by Frederick II. On September 15, after some skirmishes with the Austrians, Ferdinand moved to Nollendorf where he camped. Meanwhile, Field Marshal Count Gessler left Dresden with 41 Prussian cavalry units and camped between Zuschendorf and Krebs. On the same day, Peroni's Austrian detachment withdrew to Aussig to join Wied's corps, which had been reinforced by cavalry led by Major General Prince von Löwenstein. Browne at Budin finished receiving reinforcements, and set off on September 30 in the direction of Lobositz. Frederick II then received news that there were imperial troops near Lobositz, but his full strength was unknown. Federico fearlessly put his troops on the march. The Imperial forces consisted of 26,500 infantry, 7,500 cavalry and 94 guns (70×3, 12×6 pounder and 6×12 guns and 6 howitzers). Frederick II, for his part, had 18,250 infantry, 10,500 cavalry and 98 guns (52 × 3 pounder, 28 × 12 and 8 × 24 guns, and 10 × 10 howitzers). Frederick II remained unaware of his enemy's strength and disposition. The landscape was enveloped in a dense fog. Frederick II ascended the Homolka, but could only see that Lobositz was occupied by infantry and cavalry. Federico II ordered to bombard the positions occupied by the Austrian cavalry, which did not charge, but changed position several times, suffering heavy casualties. Federico II orders his troops to advance but the fog makes the advance difficult because it hides the defensive positions and the Austrian batteries decimate the Prussian troops.

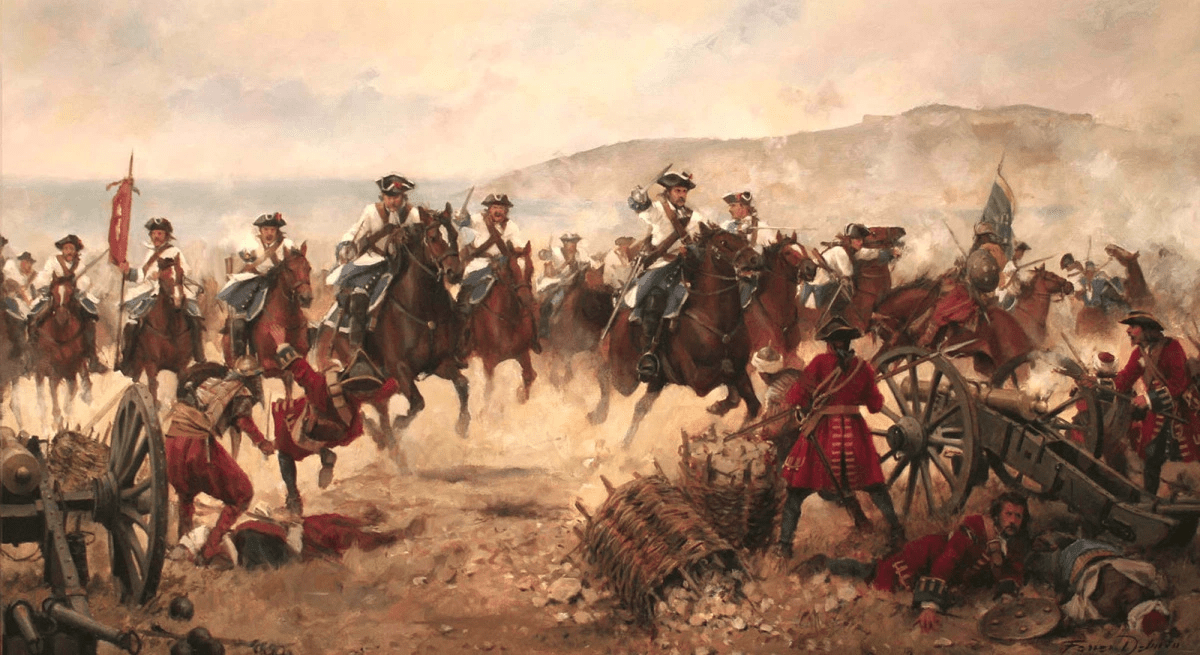

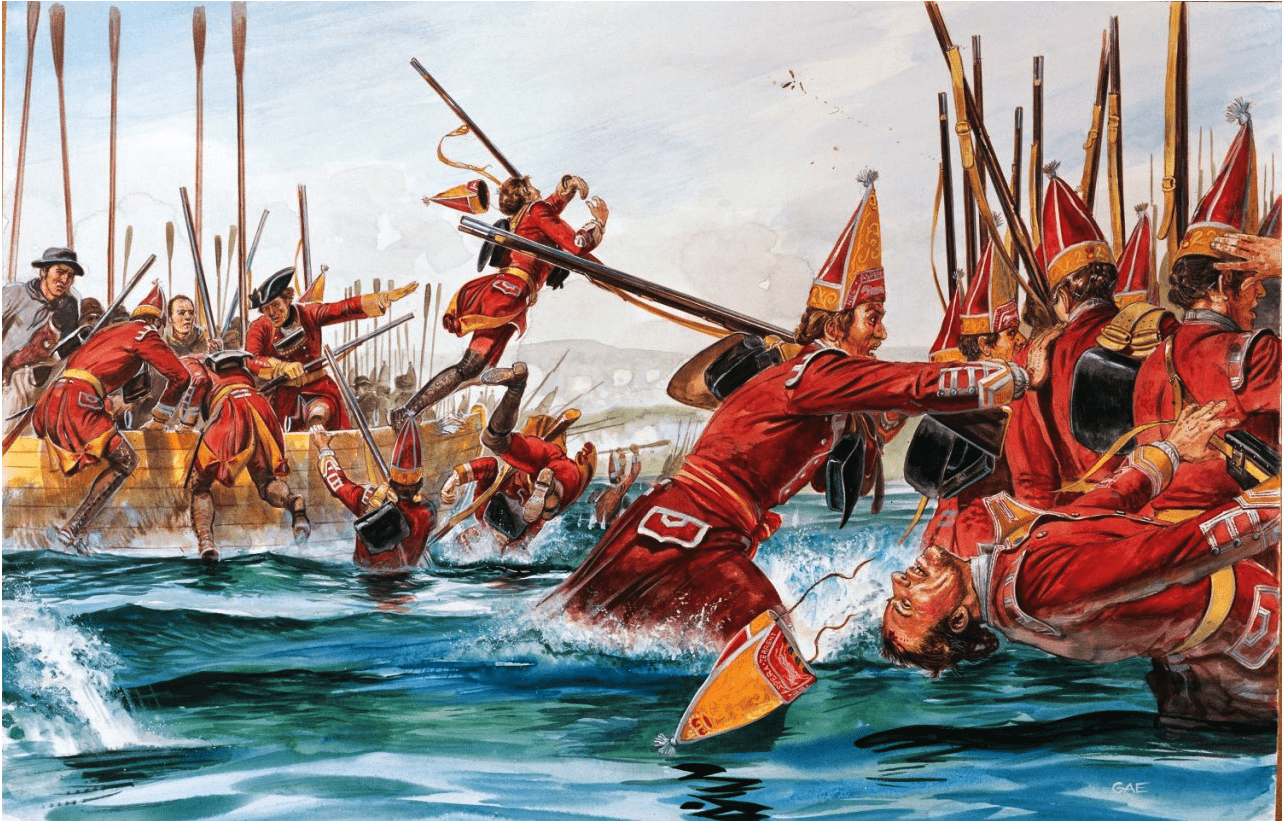

Frederick then decides to attack the cavalry troops that were visible and that, after having suffered many casualties from the artillery, are overwhelmed by the Prussian cavalry. Meanwhile, the Prussian infantry failed, time and again, in their advance. Frederick II mocked Gesler, who had led the assault, and he angrily put his sword in its sheath and, armed only with the whip, led a new attack. Two musket balls ended his life. About 10,000 Prussian infantrymen now advanced against the Austrians. Meanwhile on the left wing the Prussians had been imposing themselves. At that moment the fog lifted and Frederick II could finally see the entire battlefield and Frederick ordered an attack on Lobositz. The Prussians were still in the same positions both on the right wing and in the center. For his part, Browne had suffered significant losses, his cavalry had suffered greatly while the infantry was sheltered behind their defensive positions without ever taking the offensive. However, he could win if he took the Prussian left wing. Browne ordered the attack, engaging 4,200 men in combat, forcing the Prussian troops to retreat. But the situation soon changed and the entire left wing, once regrouped, attacked, sinking part of the imperial infantry in the Elbe. Prussian cannons set fire to several houses in Lobositz as Prussian troops attacked the town. Finally the city was in the hands of Prussia. By 3:00 p.m., the shooting had stopped almost everywhere. Lobositz was occupied by BIs from Alt-Anhalt and Zastrow. At 5:00 p.m., Browne gave the signal to withdraw and Budin was withdrawn. The battle had lasted 7 hours, the last 4 very intense. Frederick had lost 3,308 killed and wounded. Prussian Major-General Baron von Quadt and Lieutenant-General Franz Ulrich von Kleist subsequently died of their wounds. For his part, Browne lost 2,863 killed and wounded, 418 men taken prisoner, 3 × 3 guns, and two standards. This was far from a decisive victory for Frederick.

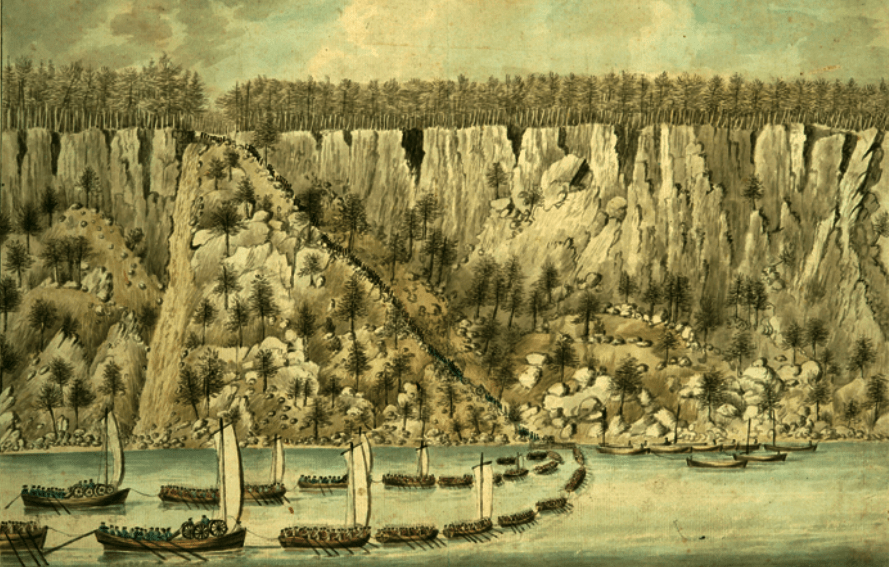

To avoid being cut off from his supplies, Browne marched back to Budin at night. The Prussians remained in the Lobositz area for a couple of weeks, awaiting Browne's reaction. The Prussian force blockading Pirna loudly celebrated the victory at Lobositz while the blockaded Saxon army felt despair at this news. Despite this defeat, Maria Theresa did not doubt her initial resolve and ordered Field Marshal Browne to relieve the Saxon army at all costs. Browne managed to get through to the Elector of Saxony, asking him to wait until October 11. He was asking a lot of the Saxon troops, as they were down to half rations and had seen an increase in sickness due to bad weather. The message was received in the Saxon camp on Thursday, October 7. On October 5, the Saxon garrison at Pirna moved to Königstein, leaving only 116 men from the Wittenberg garrison. Despite the poor conditions, desertion remained remarkably low in the Saxon army. On October 6 near Pirna, the Prussians erected a redoubt at Copitz and garrisoned it with 200 men and 4 artillery pieces. On October 7, Browne left his Budin camp at the head of a selected force of 8,000. Browne marched to Raudnitz where he crossed the Elbe and then proceeded over bad mountain roads to Gastorf and Bleiswedel. He intended to make a sweeping sweep east through the foothills of Lusatia. To conceal his departure, he had set up a chain of outposts along the Elbe between Leitmeritz and Schreckenstein. On Friday, October 8, Field Marshal Rutowski, General-in-Chief of the Saxon Army, had a squad of boatmen, helmsmen, and peasants ready to tow boats towards Königstein to build a bridge. They were escorted by a few battalions with field pieces to protect them from the Prussian battalions on the opposite north bank.

During the night of October 8-9, the flotilla of small towed boats was launched. Around 1 a.m., she was seen from the Prussian redoubt at Pötzscha who opened fire. The Saxon field pieces were no match for the Prussian ones. The towing party soon left. The escort soldiers had to replace them, but to no avail. The operation had to be interrupted. The Prussians captured 7 ships and sank a few others. Meanwhile, the Prussian Lieutenant-General von Lestwitz had rushed from Mockethal to the heights of Wehlen at the head of BI Schwerin. On October 9, Lestwitz built entrenchments on the heights of Wehlen and fired on the Saxon pontoons on the opposite bank of the Elbe. During the night of 9/10 October, another vain attempt was made to bring ships to Königstein. On Sunday October 10, considering it impossible to get boats to Königstein, Rutowski changed his plan and ordered the pontoons to be transported from Pirna to Thürmsdorf about 1.6 km from Königstein. The Saxons were supposed to cross the Elbe at Thürmsdorf under cover of cannons at Königstein. The plan called for the Austrians to take up position at Lichtenhayn while the Saxons would concentrate at Ebenheit overnight. Then the next day the Saxons would fire two cannon shots from Königstein as a signal to begin simultaneous attacks on the Prussian posts. However, on the Saxon side of the river the pontoons had not yet been assembled into a bridge. Rutowski attributed this to the small number of pontoon boats available. The Prussian General Leschwitz was sent between Schandau and Wendischefere with 11 battalions and 15 squadrons, blocking the way to Field Marshal Browne who was camped opposite this Prussian corps between Mittelndorf and Altendorf. The small plain where the Saxons intended to land was dominated by the Lilienstein Mountain. Both sides of this mountain were guarded by 5 Bns of dug-in Prussian grenadiers. Two Prussian Battalions of Jagers were deployed 500 paces back in the Burgersdorf Gorge, supported by 5 Echelons of Dragoons (ED).

On the night of October 11/12, the Prussian Major-General von Manteuffel at the head of the RI Schwerin left his camp at Mockethal. From his camp at Pirna, the Saxons could see Browne's campfires. On Tuesday, October 12, the expected signal from the Saxon army did not come. His pontooners with some officers and soldiers were still actively working on the construction of the pontoon bridge. Meanwhile, the Prussian commander was reinforcing his posts in the Lilienstein and Lichtenhayn area. From 9:00 p.m., during the night of 12/13 October, the Saxon army (18,558 men) moved in heavy rain from their positions stretching from Pirna to Hennersdorf to reach the crossing place at Thürmsdorf. Due to very narrow paths, he could only advance in a single column. The army had to abandon most of its guns on the sodden roads. At 11:30 p.m., the crossing began on the pontoon bridge, the movement was still underway when dawn broke. By this time only the converging 7 Guard Battalion (GB) had completed the crossing with their 2 battalion guns. The fog prevented the Saxon artillery from the fortresses of Sonnenstein and Königstein from covering the movement of the army. Meanwhile, the Elector of Saxony and his court had taken refuge in the fortress of Königstein. The situation worsened to the point that Browne was forced to retreat towards Hinter-Hermsdorf. On Friday morning, October 15, the Prussians occupied the Sonnenstein fortress. Meanwhile, Rutowski had returned to Struppen. Without the Elector's authorization, he opened negotiations with Winterfeldt and Frederick II. Rutowsky then informed the Elector that he had finally authorized him to negotiate a capitulation.

The Elector's main concerns were: to obtain free passage to Warsaw for himself and his court; prevent the forced integration of his army into the Prussian army; keep Königstein fortress neutral during the war, and prevent the imprisonment of his guards and cadets. However, Frederick II rejected most of these conditions. He insisted that the Elector Frederick Augustus II should simply hand over his troops. No exception was made for guards and cadets. However, Saxon officers would not be forced to serve in the Prussian army if they promised not to fight the Prussians anymore. The final terms granted to the Saxon army were difficult. On Saturday, October 16, Browne arrived at Böhmisch-Kamnitz with his main body. He was informed that the Prussians were working on a bridge at Tetschen, thus threatening his line of retreat. Browne detached Kamnitz's Tcol Loudon with 500 infantry and Tcol MacElliot with 60 hussars to attack Tetschen. Browne's son, Lt. Col. von Browne, Colonel von Kheil, Colonel von Mitrowski, and several other volunteers, also accompanied Loudon. On the evening of the same day, the capitulation of the Saxon army was signed and bread was sent to its soldiers. Frederick II then dispatched Major-General von Ingersleben with orders that all Saxon soldiers swear allegiance to him. Field Marshal Rutowski sent General von Arnim to Frederick II to protest against this move, but to no avail. On Sunday, October 17, Browne arrived at Politz. On the same day, Frederick II crossed to Niederrathen, where the rebuilt pontoon bridge was thrown over the Elbe. He then went to Waltersdorf to review the captured Saxon army. The Saxon officers were separated from their regiments and sent home (out of a total of some 600 officers, only 37 agreed to enter the Prussian service). The Saxon soldiers meanwhile passed between 2 Prussian Guards BIs and were met by the 2 Prince of Prussian Infantry Battalions. Then they put down their weapons. The Saxon regiments were forced to swear allegiance to Field Marshal Moritz von Anhalt-Dessau, who had been appointed commander of the 'new' regiments. Only a few soldiers swore allegiance, although the Prussians began to beat them. The grenadiers of the Corps Guard, the Corps Guard, the GB of Kurprinzessin and the Königin infantry refused to swear allegiance.

The loyalty ceremony lasted until October 19. The regiments secured Prussian officers and then marched to a camp between Struppen and Pirna, guarded by Prussian soldiers. Frederick tried to convince the Saxon Bodyguards to join his own Bodyguards, but they initially refused. They had to give up their sabers and Frederick threatened to distribute them among his cavalry regiments. Finally, wishing to stay with his old comrades, he accepted Federico's offer. All other captured Saxon CRs disbanded and their troops distributed among various Prussian RCs. 10 of the 13 captured Saxon IRs remained intact, dressed in Prussian uniforms and supervised by Prussian officers. The remaining 3 IRs disbanded and their soldiers distributed among the other ten. The Saxon officers were allowed to depart on parole. Later, as soon as they had the chance, the Saxon foot soldiers deserted entire companies. By the end of 1757, most of the Saxon regiments had been disbanded, and those soldiers who had not deserted were distributed among various Prussian regiments. At the end of October the Prussians withdrew to their winter quarters in southern Saxony, and the Austrians. The invasion of Saxony by Frederick's troops unleashed a wave of indignation, the effects of which reached the Imperial Diet, to the point that, believing the Prussian defeat certain, it was decreed outlawed, and the coalition determined to put 500,000 soldiers to crush the attacker. France, Austria, and Russia were willing to contribute forces to participate in the almost certain Allied victory and participate in the distribution. To defend Prussia and Pomerania from attack, Frederick II left troops to General Manteuffel and the rest of the army distributed as follows:

In Silesia and the county of Glatz he had 33,000 men commanded by Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin.

In upper Lusatia 22,000 men were quartered under the command of the Duke of Bevern.

Near Dresden 30,000 soldiers under his command.

In lower Saxony Prince Maurice of Auhalt-Dessau with 18,000 men.

At the end of March, the Imperials had 5 ACs (Army Corps) on the border:

AC-I 20,000 under the command of the Duke of Ahremberg on the banks of the Eger river.

AC-II 40,000 under Browne (who was in the last stages of tuberculosis) by the Budin River.

AC-III with 20,000 soldiers deployed in Reichenberg under Königseck.

AC-IV 27,000 under the command of Serbelloni.

AC-V in Moravia 36,000 men under Marshal Leopold Joseph von Daun. AC-V another 15,000 under Nodosky in Moravia.

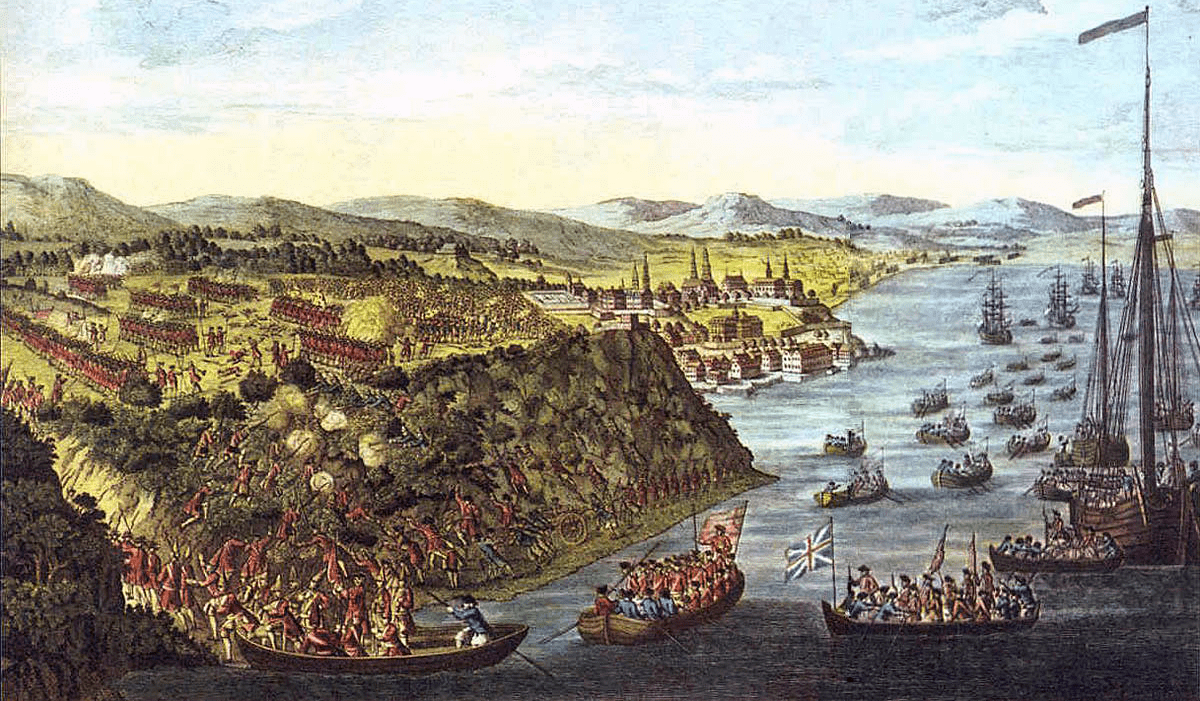

María Teresa I of Austria appointed her brother-in-law Carlos Alejandro de Lorraine as general in chief, more out of affection than for his military skills. While the much more skilled General Browne was to serve under him. This had advised that Saxony and Silesia be attacked to divert the war from the Austrian possessions, but Charles of Lorraine preferred to remain on the defensive and gather numerous forces around him. Federico waited until the steps were clear of snow. For the invasion he had 85,600 infantry in 108 Battalions, 27,900 cavalry in 163 Echelons and 2,000 artillerymen, which he framed in 4 ACs: Prince Moritz advanced from Saxony with 19,300 troops. Frederick marched south up the Elbe Valley with 39,600 troops. August Wilhelm von Brunswick-Bevern, Duke of Bevern advanced on Jung-Bunzlau with 20,300 troops, while Field Marshal Schwerin moved south from Silesia and turned west to join Bevern with 34,000 troops. The 4 Prussian ACs penetrated between April 18 and 21 through different points of Bohemia with the aim of enveloping the scattered troops and leading the imperial armies towards Prague. Prussian forces entered Bohemia through Aussig, while Prince Maurice entered directly from the Eger River. The Duke of Bevern's column joined Schwerin's at Turnau and attacked Königseck's forces, achieving a small victory at the Battle of Reichenberg on 21 April, in which 13,200 Austrian infantry and 3,500 cavalry clashed. against 11,450 Prussian infantry and 3,100 cavalry. The imperial general had to fall back on Prague, while the Prussians seized large quantities of Austrian supplies. Meanwhile, Frederick II was advancing on Prague to attack Browne before he could join forces with the Duke of Ahremberg. Browne retreated to Prague closely followed by Frederick II, joining Charles Alexander of Lorraine on April 30 near Prague.

On May 1, the imperial army withdrew to Prague, the left wing, led by Lorraine, camped on the right bank of the Vltava River, and the right wing, led by Browne, took up positions at Malleschitz. On May 5, Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine, leading 61,000 troops, took up a strong position and resolved to remain on the defensive until reinforcements arrived from Daun, rushing in from Moravia. The left wing was covered by the Ziskaberg, a steep hill overlooking the Vltava River. Along its front ran a deep ravine with steep sides, and to its right was a swamp with hedgerows, drains, and dikes, stretching up to a hill near Sterboholy. Their position was strengthened by the works and they were covered by a large artillery. On the same day Frederick crossed the Vltava River at Seltz, about 7 km downstream from Prague, and joined Schwerin. Field Marshal Keith had been left on the left bank of the Vltava with 32,000 troops. Frederick with the combined army on the right bank had 65,000 troops. As soon as the joining of his army was effected, Frederick II rode in company with Schwerin, Wintefeldt, and some aides to a ridge east of Prosek from where he could see all the Austrian positions. While his columns rested, Frederick spent some time surveying these positions with his spyglass and finally decided to engage in battle the same day, considering that any delay would allow the Lorraine army to be reinforced. Early on the morning of May 6, the entirety of the Prussian units formed up and prepared to lead the Austrians into a decisive battle. According to Frederick II's plans, Prince Maurice was to build a bridge of ships across the Vltava above Prague, cross the river with the entire right wing of Keith's corps, and charge into the enemy's rear while the King attacked front and side.

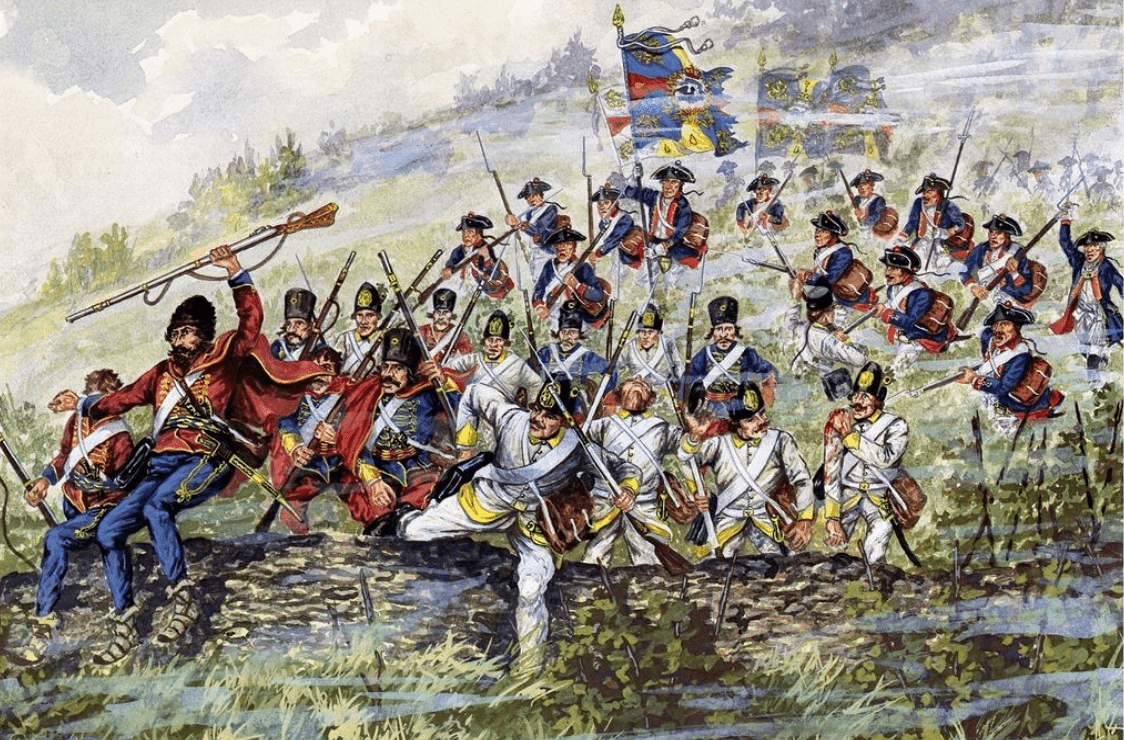

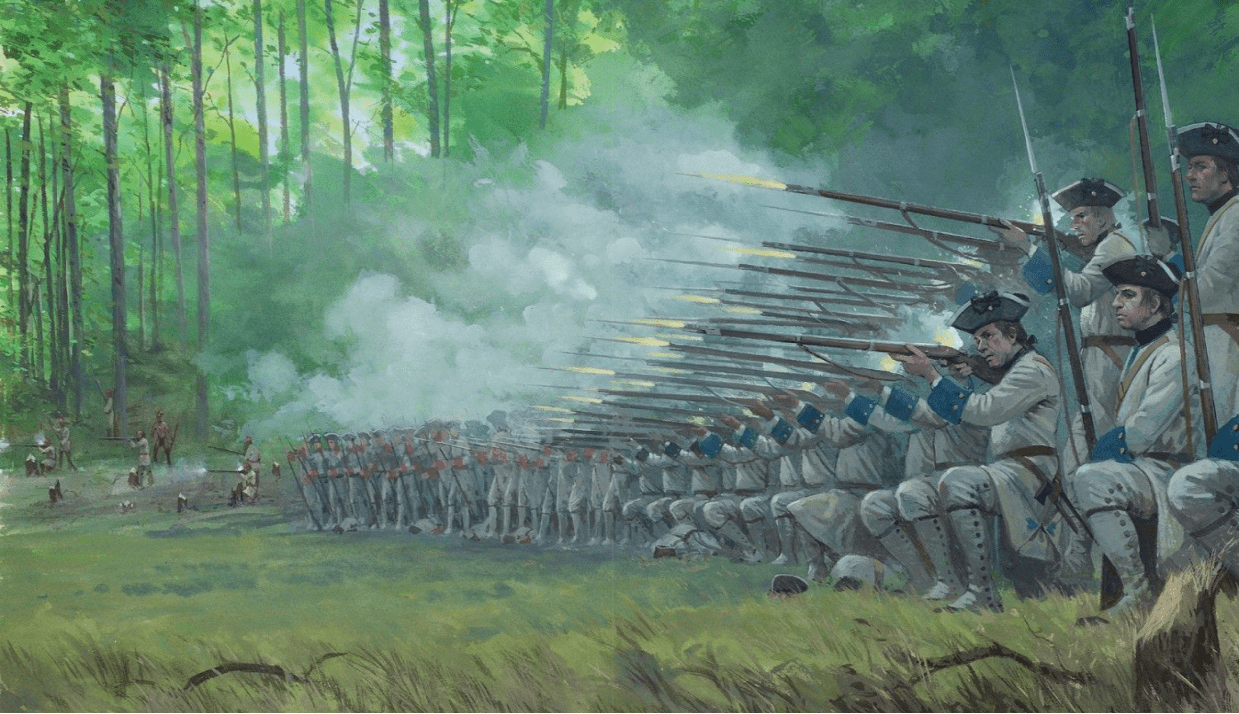

Schwerin and the other generals wanted to dissuade him from this plan, which they believed was too audacious. These generals objected that the troops had come a long way and were weary, that the ground on which the battle would be fought seemed uncertain and had not been sufficiently examined. Frederick, however, silenced all scruples by remarking that it was necessary, saying "the freshest eggs are the best." But Schwerin, who was seventy-three years of age, with that youthful vivacity for which he was remarkable, lowering his hat to his forehead, he replied. "If it is necessary to be defeated, today I will go to look for the enemy wherever I see him." General Winterfeld, who was the one who had perfunctorily surveyed the battlefield, did not notice the ground behind which the right wing was positioned. Near the village of Sterboholy ran a small stream, in which ponds are formed by means of dams. These ponds had been drying up and the ground was sown with oats. The oats gave the appearance of a solid base to points that later ended up being small swamps of mud and mud. At eleven o'clock, the attack of the Prussians' left wing began. The Prussian cavalry had numerical superiority (17,000 Prussians against 13,000 Imperials) and therefore it was they who initiated the attack. The imperial cavalry began the battle with impetus and was able to repulse the Prussians twice. On the third attack, however, they were forced back. The Prussian infantry marched forward, attacking to the left, through the village of Potscherwitz, but their advance was greatly slowed when what appeared to be meadows were actually dry ponds planted with oats, forcing them forward. sinking knee-deep in mud and swamp or marching over dikes and narrow paths barely a meter wide.

Prince Charles Alexander was forced, by Marshal Schwerin's move, to change his position by drawing back his right wing, and ordered his second line to advance to protect that flank. Consequently, as soon as the Prussians were able to form up, they were met by a well-formed line assisted by a battery of 12 guns. Two entire Prussian regiments gave way, and the King, approaching, rebuked them for their cowardly behaviour. Schwerin was in the gorge when he saw his regiment waver in front of the battery. Stung by the king's reproaches, he tore a flag from the hands of an ensign and, placing himself at the head of his regiment, shouted: "A coward who dares not follow me." The old marshal did not take more than five steps, when he was hit by five bullets, falling dead under the flag that he carried in his hands. General Manteufel immediately took his place, but shortly afterwards he also fell dead from the impact of a cannonball. It was now close to one o'clock and the Prussians had advanced to within sixty paces of the enemy, but were forced back again by the Imperial right wing which, under Marshal Browne's orders, rushed forward unaware that their Their advance separated them from the rest of the army, which would be decisive for the course of the battle. This attack was commanded by Browne himself, when a cannonball shattered his right leg. He fell from his horse and was carried unconscious from the battlefield. At about the same time Charles Alexander of Lorraine, seeing his troops retreating, succumbed to a fit of cramps that rendered him unconscious and had to be evacuated from the battlefield. Thus, the Austrian army found itself for most of the battle without any commander-in-chief, so each of the divisional generals acted independently of the rest. The center of the Prussian army had advanced unmolested and threatened the left flank of the imperial right wing.

The impetuosity of the Prussian attack was irresistible and forced the Imperials back. The Duke of Bevern's troops had meanwhile passed the Hostawitz Gorge and, after very fierce fighting, advanced towards Malleschitz and seized a battery which lay beyond that village. However, they were forced to abandon it in the face of a counterattack by Königseck's troops. Prince Henry marched against three Imperial divisions, which had the advantage of terrain and were backed by far superior artillery. These Austrian troops tried to hold their position. The Prussian forces climbed the hill dislodging the Imperials from their positions. Seven redoubts were stormed, after fierce fighting, and when they found their way cut by a wide moat which made the soldiers hesitate, Prince Henry was the first to jump into the ditch causing the soldiers to advance behind him towards a great redoubt that was also finally conquered. The artillery that was positioned in this redoubt turned on the Austrians dislodging them from that position, so that Bevern was able to retake the redoubt near Malleschitz, and the retreating Austrians' resistance became weaker. Four times Königseck strove to form a new line of battle, but the Prussians constantly followed him, so that his only chance of protection lay in Prague. Although the Prussian attack was successful in the center, the Austrian right flank pushed the Prussians back, so the battle was still indecisive. These troops advanced with great impetus, separating themselves from the rest of the army. This fact was observed by Federico II, who sent some battalions to occupy the space left vacant by the imperial column, separating the central body from the enemy. This move threw the Imperials into disarray and recharged the retreating Prussians, putting the Imperials in the crossfire.

These imperial troops, finding it impossible to rejoin the rest of the army, retreated towards Benesov in the hope of being able to join Daun's troops. The Austrian left wing was still in its original position on the Ziskaberg, without having fired a shot. The Prussian right wing, under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, had passed the ravine and climbed up the steep sides of the Ziskaberg hill. The Prussian army had broken through the Austrian line and rushed at the imperial army from all sides. The redoubts, however, still intact and defended by some of Austria's elite Grenadier troops, held out for a considerable period of time, but in the end the Grenadiers had to give in to the Prussians' impetus. Around three in the afternoon, the fight was over. After the victory of their comrades on the right bank of the Vltava, the corps of 30,000 Prussians, who had remained on the left bank to cover the initial contact between the army and the route from which communication reached it under the command of Marshal Keith , prevented the defeated imperial army from withdrawing to the left bank of the Vltava, forcing him to seek refuge in Prague. Prussian casualties were 13,301 men killed, wounded, and missing, of whom 401 were officers, including Field Marshal Count Schwerin and Major General von Amstell killed; and Lieutenant-General Fouqué, Lieutenant-General von Hautcharmoy, Lieutenant-General Winterfeldt, General-Major von Schöning, General-General von Plettenberg, General-Major von Blanckensee and General-General von Kurssell wounded. The Prussians captured 33 guns, a large number of colors, 11 standards and 40 pontoons. The Austrians 13,324 men, of whom 401 were officers, were taken prisoner including 40 officers and 4,235 soldiers.

Field Marshal Browne had been mortally wounded, the Marquis de Clerici seriously wounded, and Major-General Count Peroni dead. The Austrians captured 4 battalion guns, 3 colors and 1 standard. Although the Prussians still owned the battlefield, they had failed to annihilate the Austrian army that had been allowed to take refuge in Prague. Frederick had no choice but to besiege Prague, hoping to capture it before Daun's arrival with his aid army. After the Battle of Prague, Frederick abandoned his practice of requiring the Prussian infantry to advance without firing. The battle taught him the importance of infantry firepower. Frederick with his severely reduced force was not strong enough to storm Prague. However, he decided to besiege the city in hopes of forcing it to surrender due to lack of supplies. An Austrian force of 40,000 soldiers was trapped in the city, although they were not strong enough to consider breaking the siege. Frederick tried to get information inside Prague for which he sent Christian Andreas Käsebier several times to the besieged city.

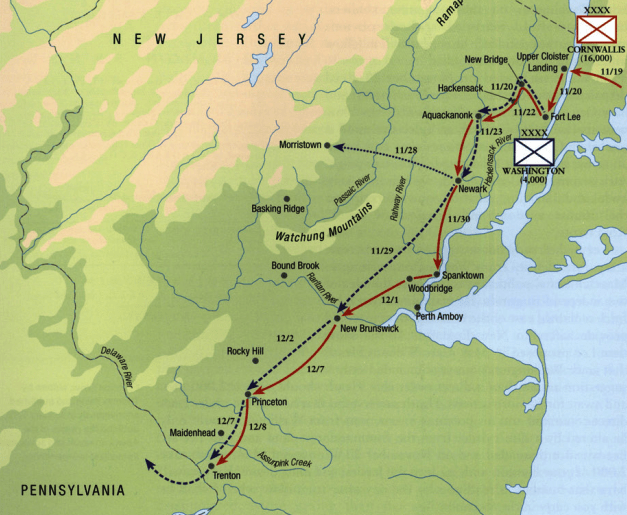

Although the war started well for the Prussians, it soon went downhill when in 1759, when a 48,000-man Prussian army commanded by Frederick II would face a combined 80,000-man army of Russian-Imperial forces commanded by Pyotr Saltykov near Kunersdorf. The battle of Kunersdorf would mean the loss of 20,000 men among deserters, wounded and dead, about half of the Prussian forces. Berlin would soon be occupied by Russian forces who would end up raping, robbing and murdering the citizens of the German city. The fate of Prussia was saved when in January 1762, at the age of 52, the death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia occurred, an event that could be explained by the long illness and age of the sovereign. In a moment of divine luck, Frederick would discover that the new Tsar Peter III of Russia was a great admirer of Frederick the Great as well as of the Prussian army's discipline and efficient administration; days after assuming the throne, and taking advantage of the suspension of war activities for the winter, Peter III of Russia ordered his troops to cease fighting against Prussia immediately and return to Frederick the Great all the occupied Prussian territory, without demanding any advantages or benefits in return. compensation. In a matter of days, Austria would remain the only great enemy of the Kingdom of Prussia, but without the decisive support of several thousand Russian soldiers, soon the court of Vienna also had to agree to peace with Frederick the Great. The unexpected peace with Russia, and the fact that Tsar Peter III did not put conditions on it, strengthened the Prussian kingdom and allowed it to ultimately survive, forcing first Austria and then France to sign a final peace with the Prussians.