«estas Colonias Unidas son, y por derecho deben ser, estados libres y soberanos».

«these United Colonies are, and by right must be, free and sovereign states».

— Attributed to Continental Congress on July 2, 1776.

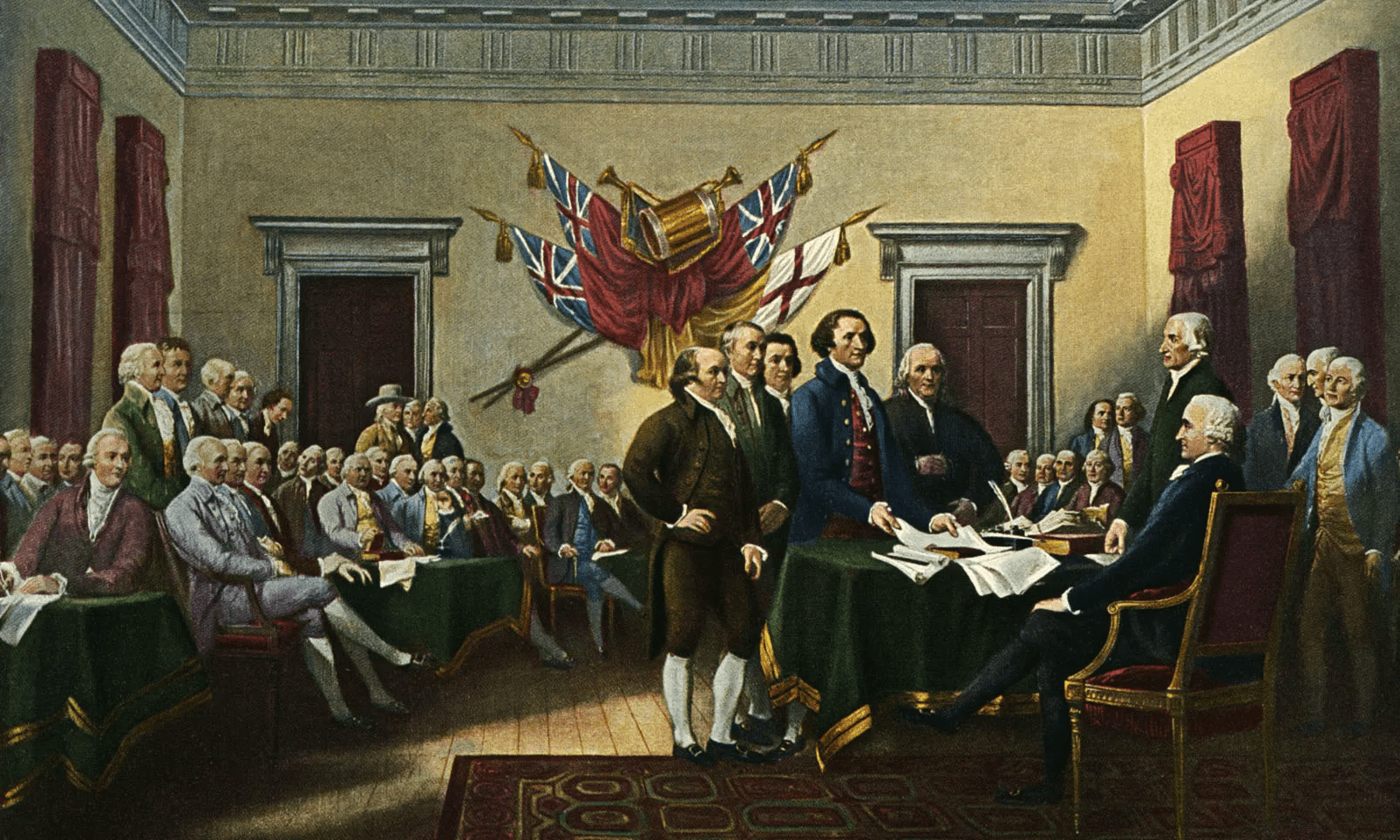

On July 2, 1776, Congress finally resolved that "

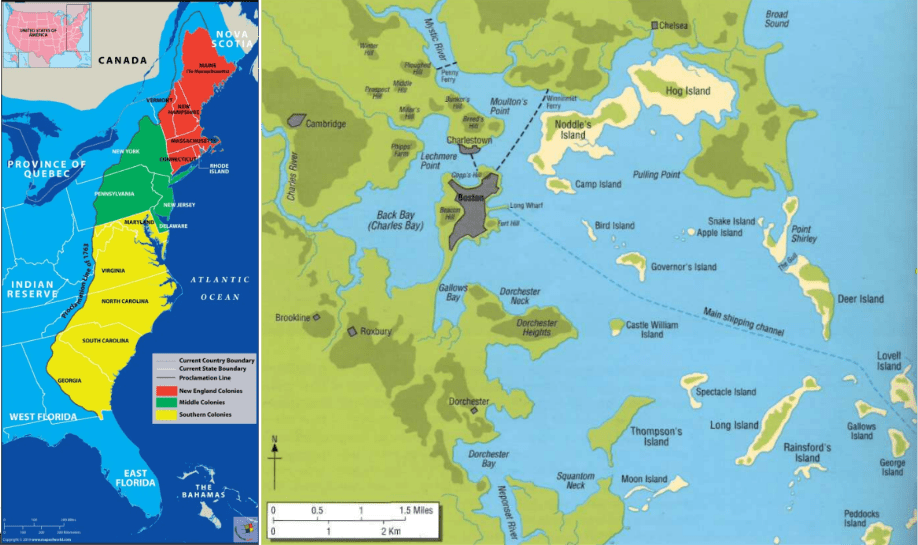

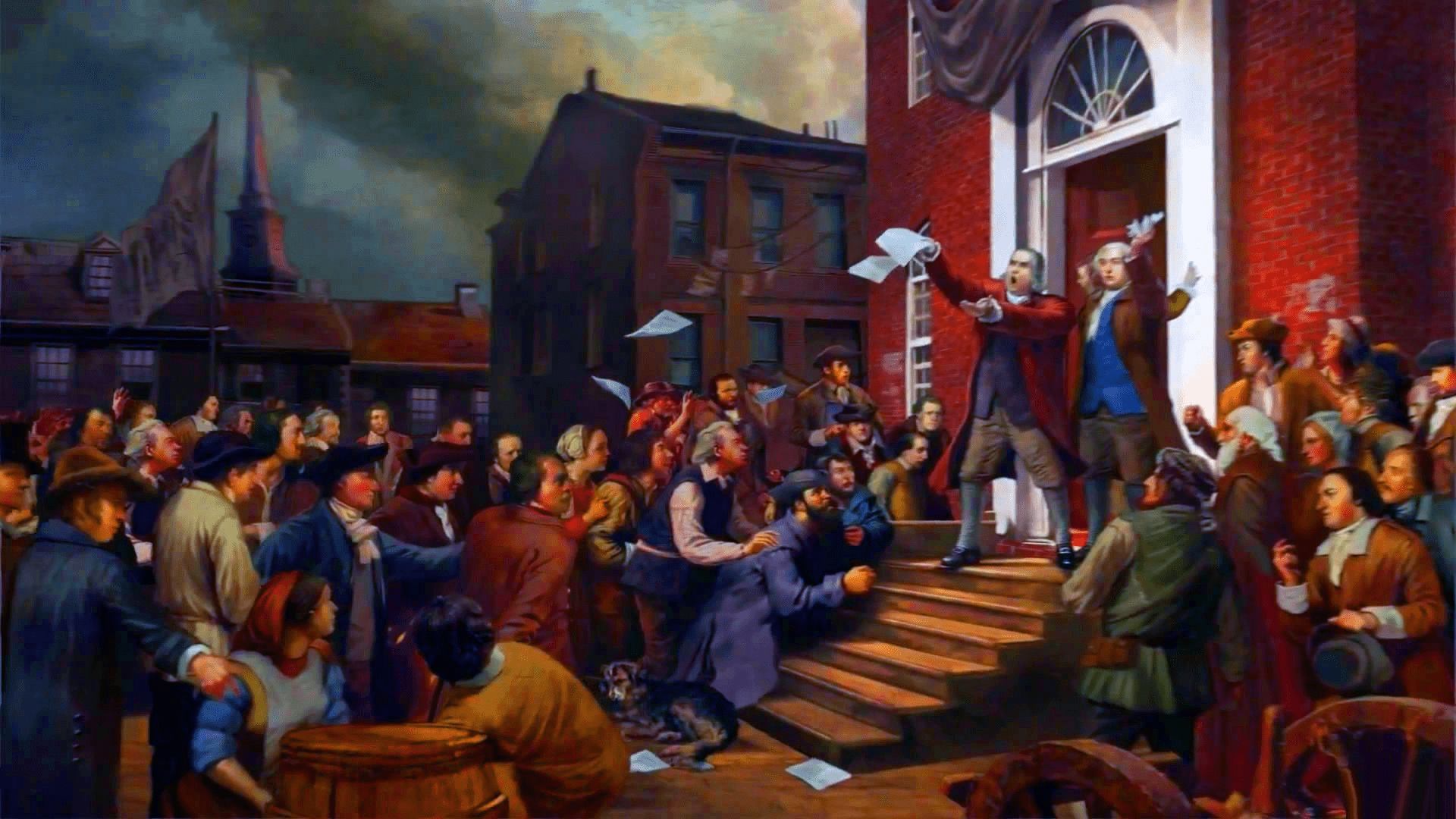

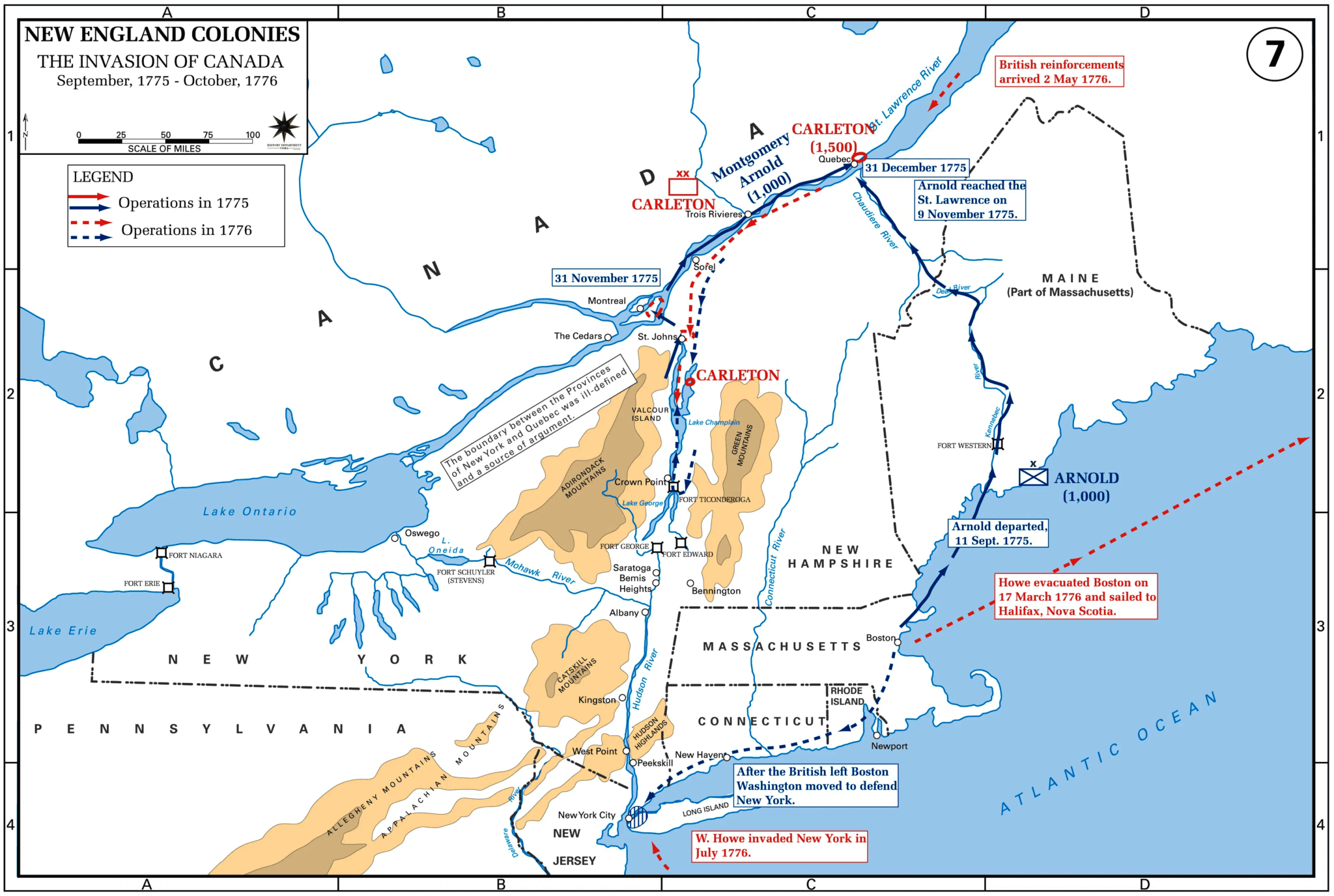

these United Colonies are, and by right ought to be, free and sovereign states." On July 4, 1776, 56 American congressmen met to approve the Declaration of Independence of the United States, which Thomas Jefferson wrote with the help of other citizens of Virginia. Paper money was printed and diplomatic relations with foreign powers began. In Congress were four of the main figures of independence: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams. Of the 56 congressmen, 14 would die during the war. Benjamin Franklin became the first ambassador and head of the secret services. The unit then spread out across the Thirteen Colonies to fight the British. The statement presented a public defense of the War of Independence, including a long list of complaints against the English sovereign George III. But above all, he explained the philosophy that supported independence, proclaiming that all men are born equal and have certain inalienable rights, including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that governments can govern only with the consent of the governed; that any government can be dissolved when it fails to protect the rights of the people. This political theory originated with the English philosopher John Locke, and occupies a prominent place in the Anglo-Saxon political tradition. These events convinced the British government that it was not simply dealing with a local New England revolt. It was soon assumed that the United Kingdom was involved in a war, and not in a simple rebellion, so conventional eighteenth-century military policy decisions were made, consisting of maneuvers and battles between organized armies. The theater of war was a long coastal strip stretching more than 2,000 km between the St. Lawrence River and Florida, with an average width of 235 km. The country was roadless and largely uncivilized, strategically favored defensive, and difficult to subdue.

It was divided into three sectors:

- Northern sector that included New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York.

- Central sector with New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Rode Island, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia.

- South sector the two Carolinas and Georgia.

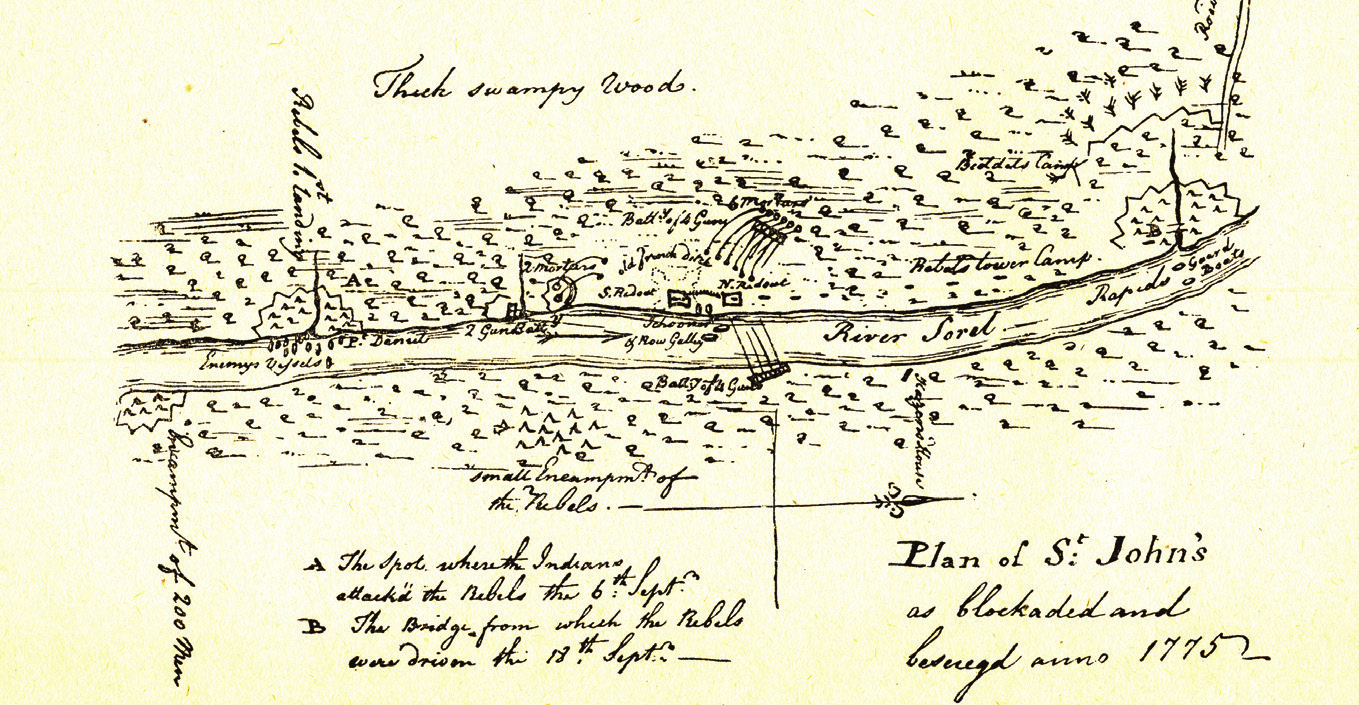

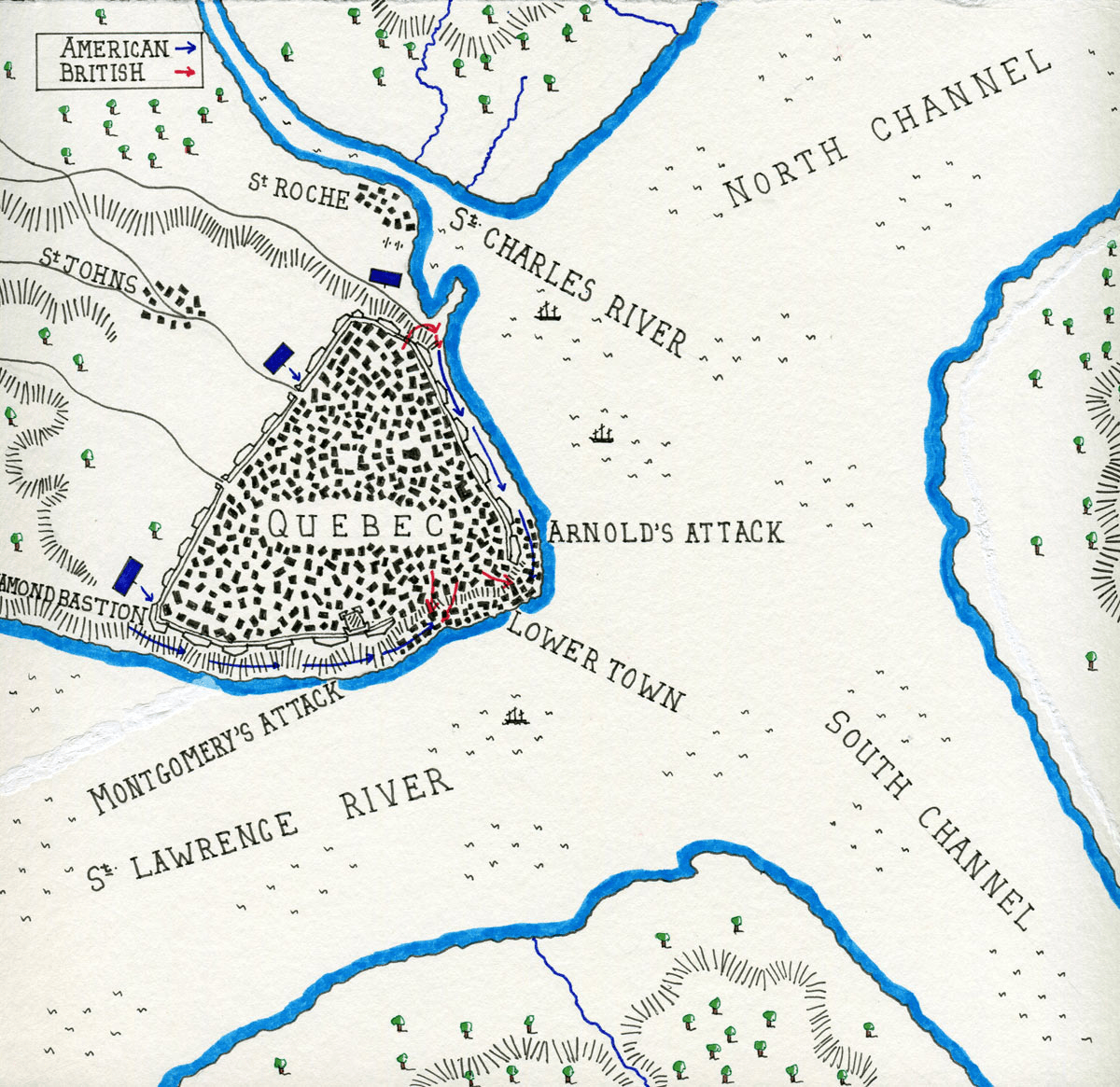

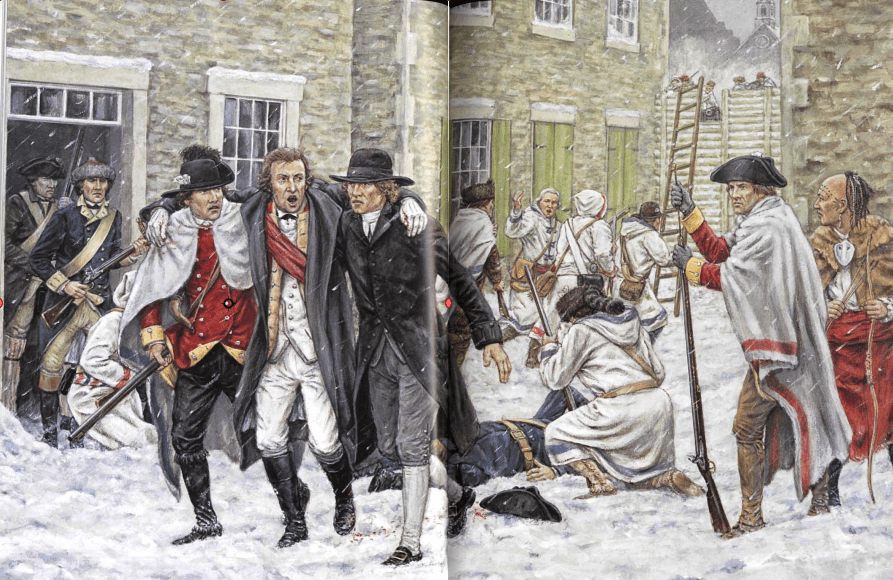

Simultaneously reducing all three sectors was impossible for Great Britain, and therefore required defeating them one by one separately. As the northern sector was the easiest to invade because Canada could be used as a base of operations, if the rebellion was crushed in New England and New York, and the English army was provided with sufficient forces, the chances of ending the conflict were high. although the central and southern sectors continued to resist, which could be gradually subdued later.

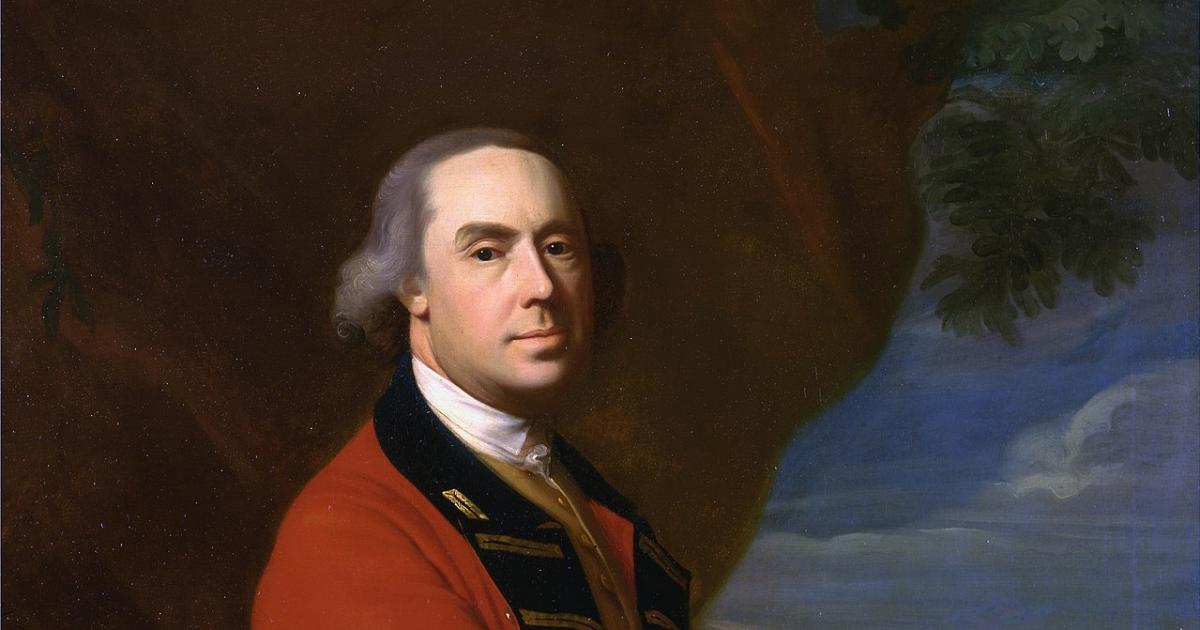

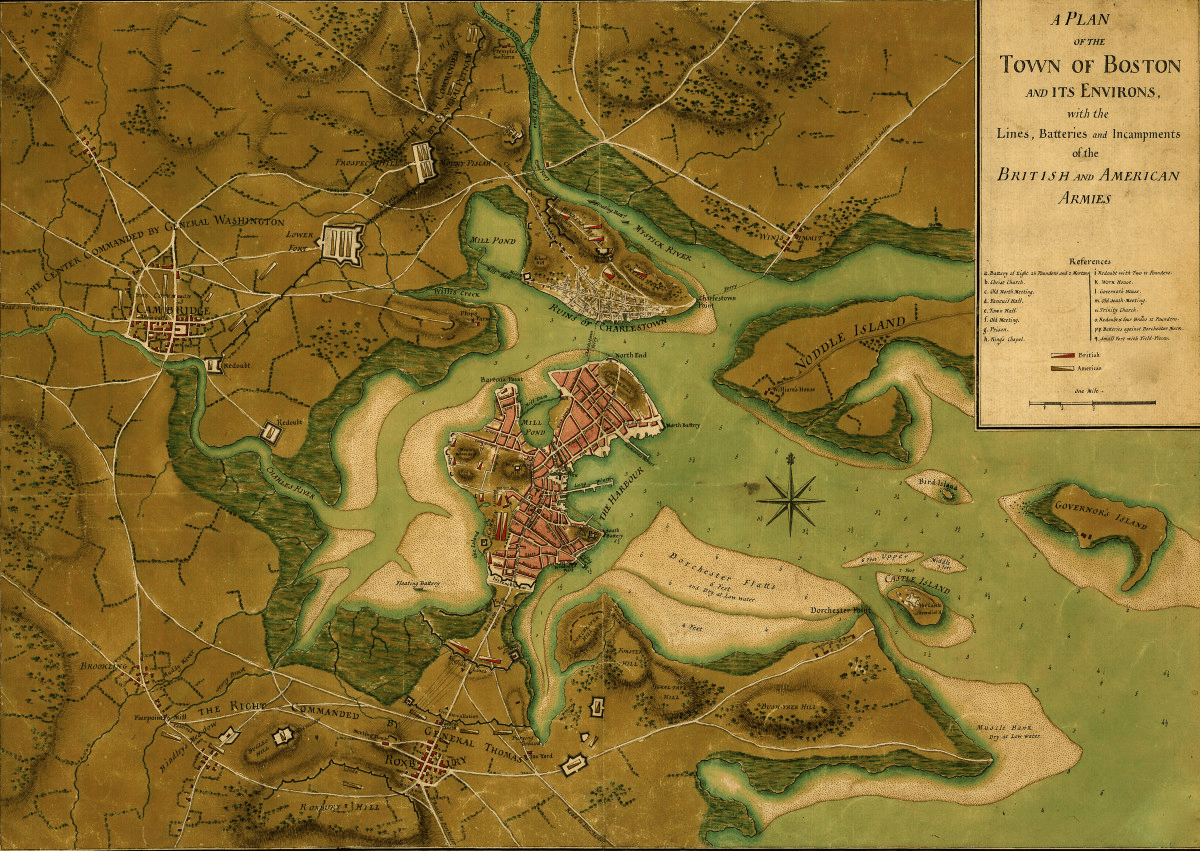

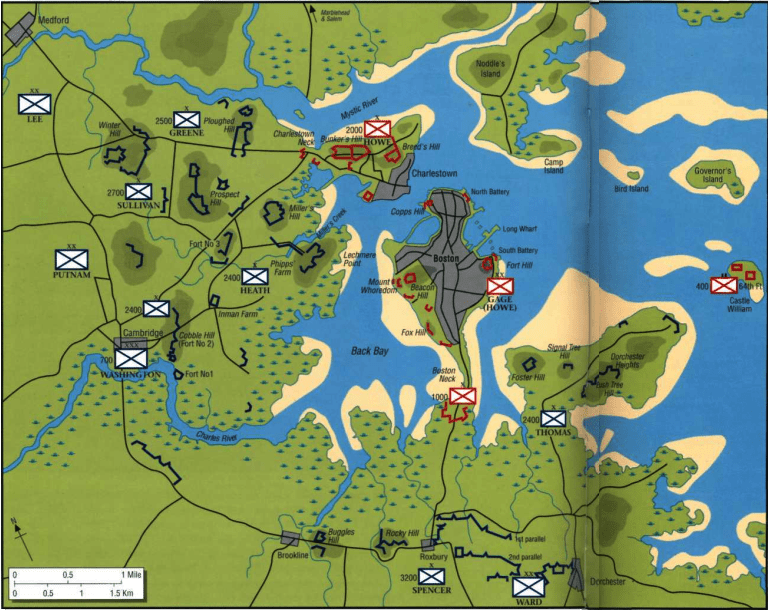

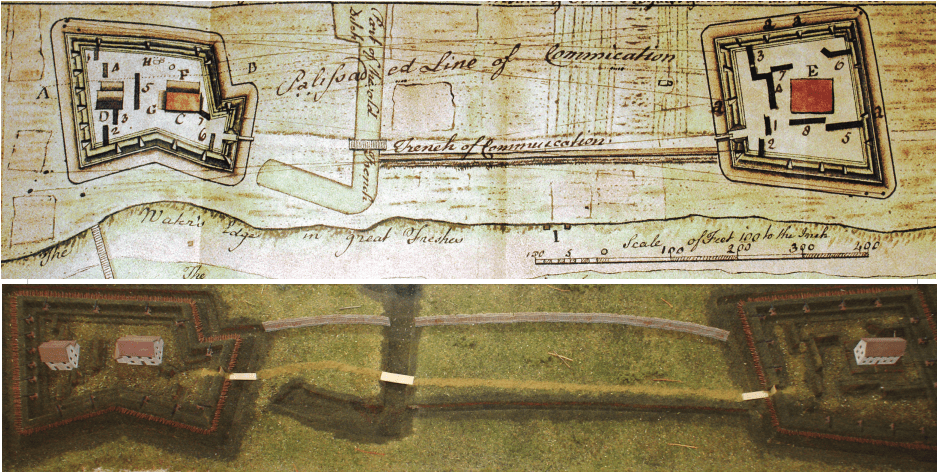

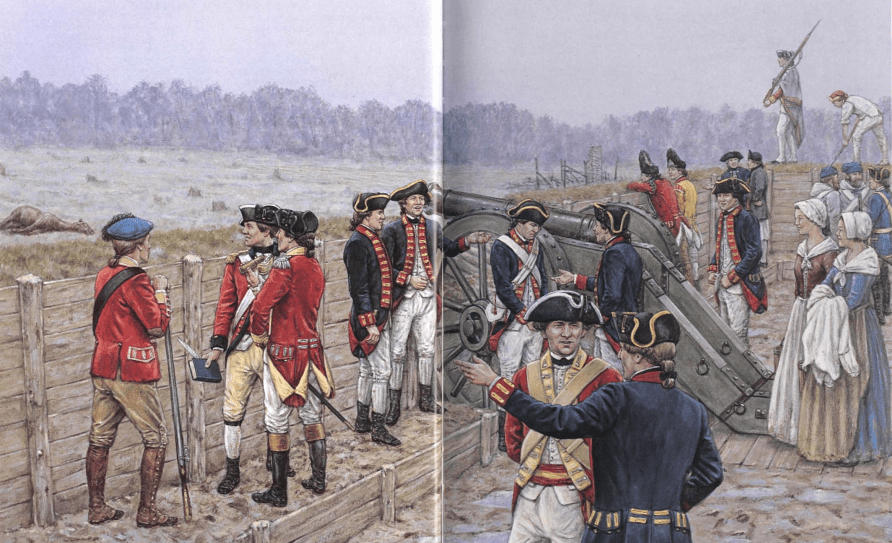

After defeating the British at the Siege of Boston on March 17, 1776, Commander-in-Chief George Washington redeployed the Continental Army to defend the port city of New York, located on the southern tip of Manhattan Island. Washington understood that the city's harbor would provide an excellent base for the Royal Navy, so he set up defenses there and waited for the British to attack. Washington left Boston on April 4, arrived in New York on April 13, and made his headquarters at Archibald Kennedy's former home on Broadway across from Bowling Green. Washington had sent his second-in-command, Charles Lee, to New York in February to set up the city's defenses. Lee remained in New York City until March, when the Continental Congress sent him to South Carolina. The construction of the city's defenses was left to General William Alexander. The troops were in limited supply, so Washington found the defenses incomplete, but Lee had concluded that in any case it would be impossible to hold the city with the British commanding the sea. He reasoned that defenses should be placed with the ability to inflict heavy casualties on the British if they made any move to take and hold ground. Barricades and redoubts were established in and around the city, and the bastion of Fort Stirling was built across the East River on Brooklyn Heights, facing the city. He subsequently built two more forts Defiance and Cobble Hill to complete Brooklyn's defenses. Lee also made sure that the immediate area was free of loyalists.

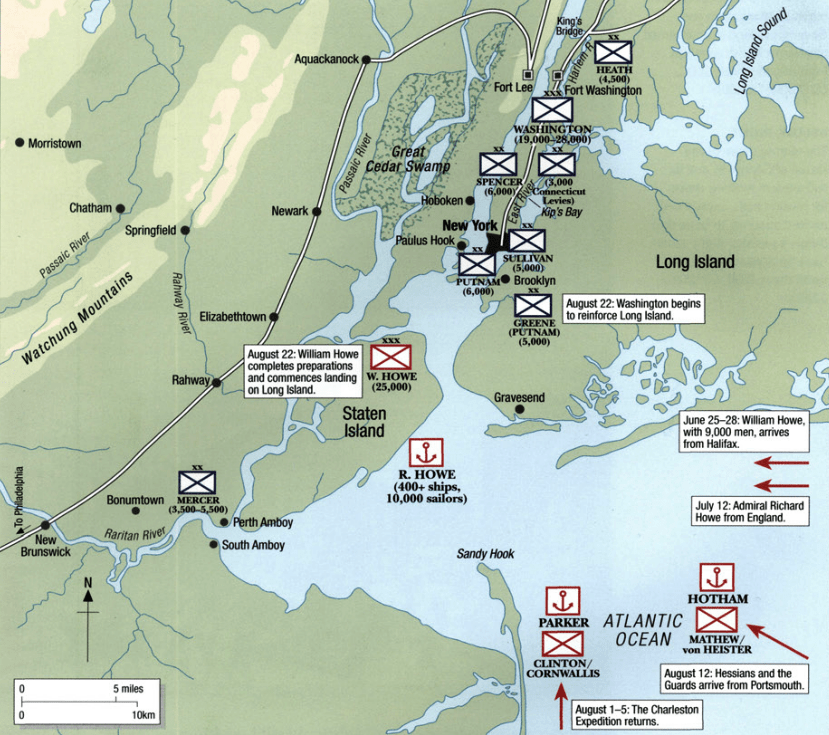

A series of rises on Long Island, the Gowanus Heights, was later adopted as a forward defensive line. Initially just an additional zone of resistance, but Washington came to see that as the best chance of stopping the British. The slope was gentle on the defending side, and steep and heavily wooded on the other side, with walkable areas in only a small number of places. Troops were posted at every pass behind felled trees and it was hoped that the British would go no further. Washington based his strategy on the hope that the British would be unimaginative in assaulting him. Under the leadership of Israel Putnam, the Americans also seized and fortified Governor's Island and sank ships between it and the battery at the tip of Manhattan to prevent the passage of British ships. They did not do any further defensive work to protect the strait between the islands of Staten Island and Long Island, but they seemed to have limited resources and manpower. They had done what they could, but Washington rightly had a feeling. “We are expecting a very bloody summer…” he wrote to his brother on May 31, “and I am sorry to say that we are not prepared, neither in men nor in arms.” In July, the British, under the command of General William Howe, landed a few miles across the harbor on the sparsely populated Staten Island, where they were reinforced by a fleet of ships in New York Bay for the next month and medium, bringing its total strength to 32,000 soldiers. Washington knew the difficulty of holding the city with the British fleet in control of the harbor entrance at the Narrows, and accordingly moved most of his forces to Manhattan, believing that it would be the first target. The American army had about 28,500 men gathered around New York to oppose the British.

Indignity gripped the men as the disease swept through New York and more than a quarter of Washington's army was disabled, giving him just under 20,000 men fit for service. Less than half of this force were from the Continental Army, with the rest being state troops or militia. Washington was also almost totally devoid of cavalry; in fact, he had turned down Connecticut's offer of 3 RCs in June, numbering about 400, they could have done very valuable work patrolling the outlying American defenses, but Washington believed that the difficulty in feeding the horses would outweigh their usefulness ( a curious belief given the time of year and the abundance of suitable forage on Long Island). He asked the men to serve as foot soldiers, with their horses sent to Westchester to serve as roustabouts for officers or as work animals. The Connecticut Riders rejected that offer. The development of operations on Long Island would show the lack, as the only body of mounted troops was the Long Island Militia, under Nathaniel Woodhull, and they were employed exclusively to round up and herd cattle to prevent them from falling into British hands. Washington was not sure where the British would attack. Both Greene and Reed thought the British would attack Long Island, but Washington thought a British attack on Long Island might be a diversion for the main attack on Manhattan. He divided his army into two parts, half stationed in Manhattan and the other half on Long Island. Greene would command the army on Long Island. On August 20, Greene fell ill and was forced to move to a house in Manhattan where he rested to recover. John Sullivan took over command until Greene recovered. General Howe had sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, arriving at Sandy Hook on June 9, 25 arriving in New York Harbor with 9,000 troops in 45 ships. On June 29, a fleet of 130 ships and more than 9,000 soldiers arrived from England under the command of Admiral Richard Howe, the general's brother.

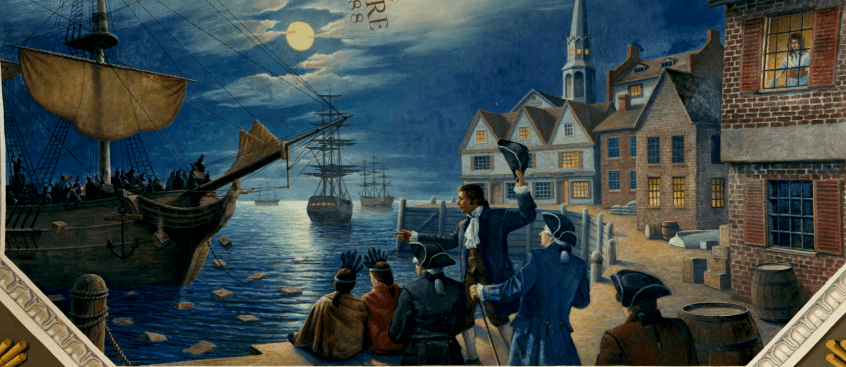

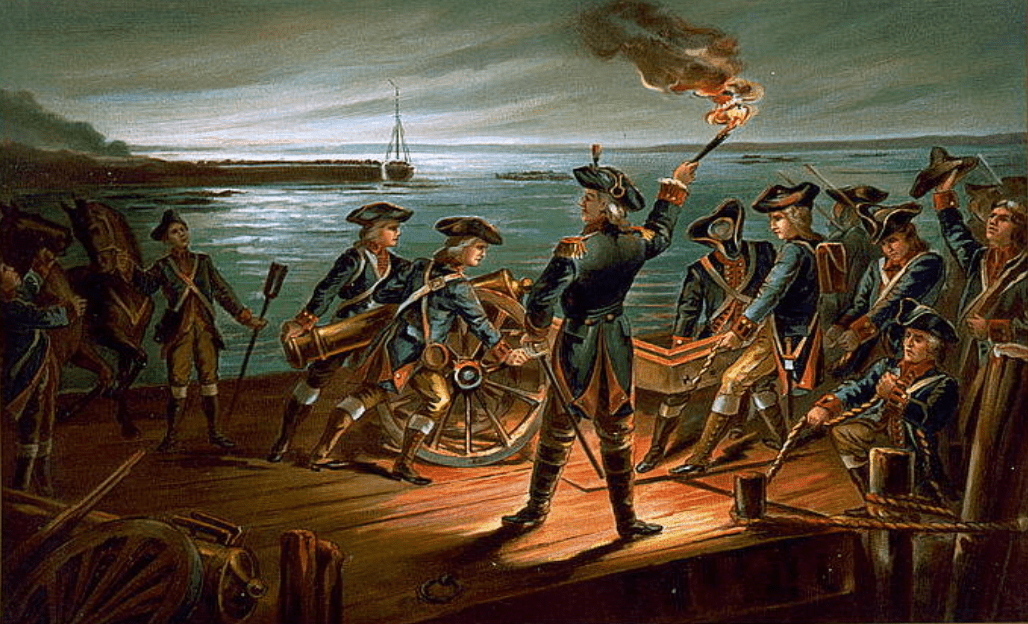

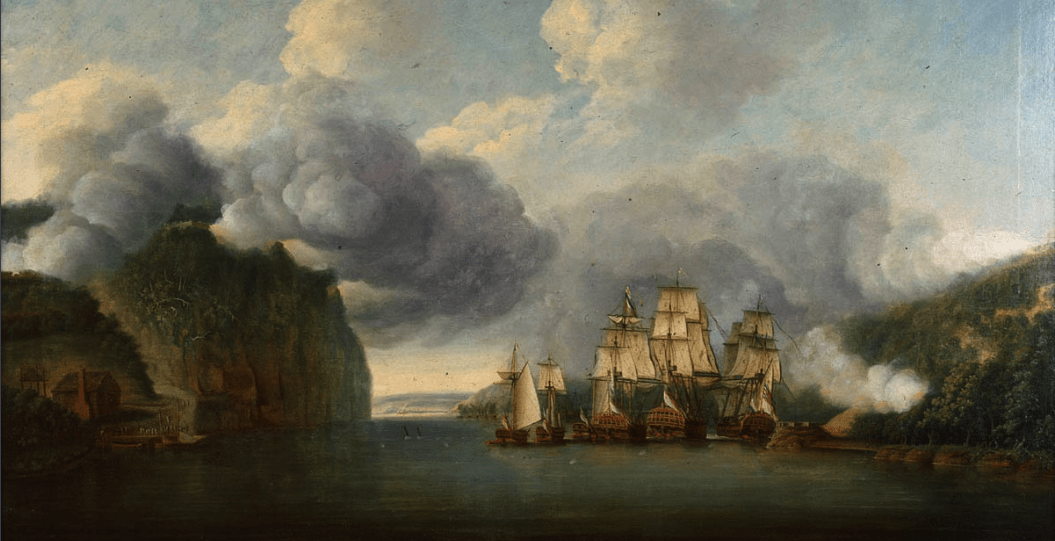

The combined fleet anchored off Staten Island, whose inhabitants were known to be loyalists. The garrison and New Yorkers crowded onto the docks to watch the spectacle. Howe sent several officers to invite Washington to parley, but he refused, as they did not recognize his title as General of the Congressional Army. On July 2, British troops began landing on Staten Island. Continental soldiers on the island shot at them before fleeing, and the militia went over to the British side. On July 6, news reached New York that Congress had voted for independence four days earlier. On Tuesday, July 9, at 6:00 p.m., Washington had several Brigades march to the city commons to hear the Declaration of Independence read. After the reading, a crowd ran to Bowling Green with ropes and bars, where they toppled the gilt-bronze equestrian statue of George III of Great Britain. In their fury, the mob lopped off the statue's head, cut off its nose, and mounted what was left of the head on a spike outside a tavern, with the rest of the statue being dragged to Connecticut and melted down into 47,000 musket balls. . On July 12, the British ships Phoenix and Rose sailed through the harbor toward the mouth of the Hudson. American batteries opened fire from Fort George, Red Hook, and Governors Island, and the British returned fire on the town. The ships sailed along the New Jersey shoreline and continued up the Hudson River, past Fort Washington and arriving in the evening at Tarrytown on the widest part of the Hudson. The objectives of the British ships were to cut off American supplies with New England and the North, and to encourage loyalist support. The only casualties of the day were six Americans who were killed when their own cannon exploded. The next day, July 13, Howe attempted to open negotiations with the Americans.

He sent a letter to Washington delivered by Lieutenant Philip Brown, who arrived under a flag of truce. The letter was addressed "George Washington, Esq." Brown was met by Joseph Reed, who had rushed to shore on Washington's orders, accompanied by Henry Knox and Samuel Webb. Washington asked his officers whether he should receive him or not, since he did not recognize his rank as a general, and they unanimously said no. Reed told Brown that there was no one in the military with that address. On July 16, Howe tried again, this time with the address "George Washington, Esq., Etc., etc.", but was again rejected. The next day, Howe dispatched Captain Nisbet Balfour to ask if Washington would meet General Howe's aide face-to-face, and a meeting was scheduled for July 20. Howe's aide was Colonel James Patterson. Patterson told Washington that Howe had come with clemency powers, but Washington said, "Those who have done no wrong don't want pardon." Patterson departed soon after. Meanwhile, on August 1, Peter Parker's fleet of 30 ships, with Generals Clinton and Cornwallis, returned from the abortive assault on Charleston, with another 3,000 troops. As news of the expedition's defeat spread, it seemed to cheer the New York garrison, but Washington called this development alarming. Later, on 12 August, 8,000 Hesse-Kassel mercenaries arrived from Portsmouth, bringing Howe's force to 32,000 soldiers, 10,000 sailors, and 2,000 marines. At this point the British fleet numbered over 400 ships, of which 73 were warships, the largest expedition of its kind ever mounted by Britain and certainly the largest fleet ever seen in America. Howe's options for the full command assault on the narrow waters were several.

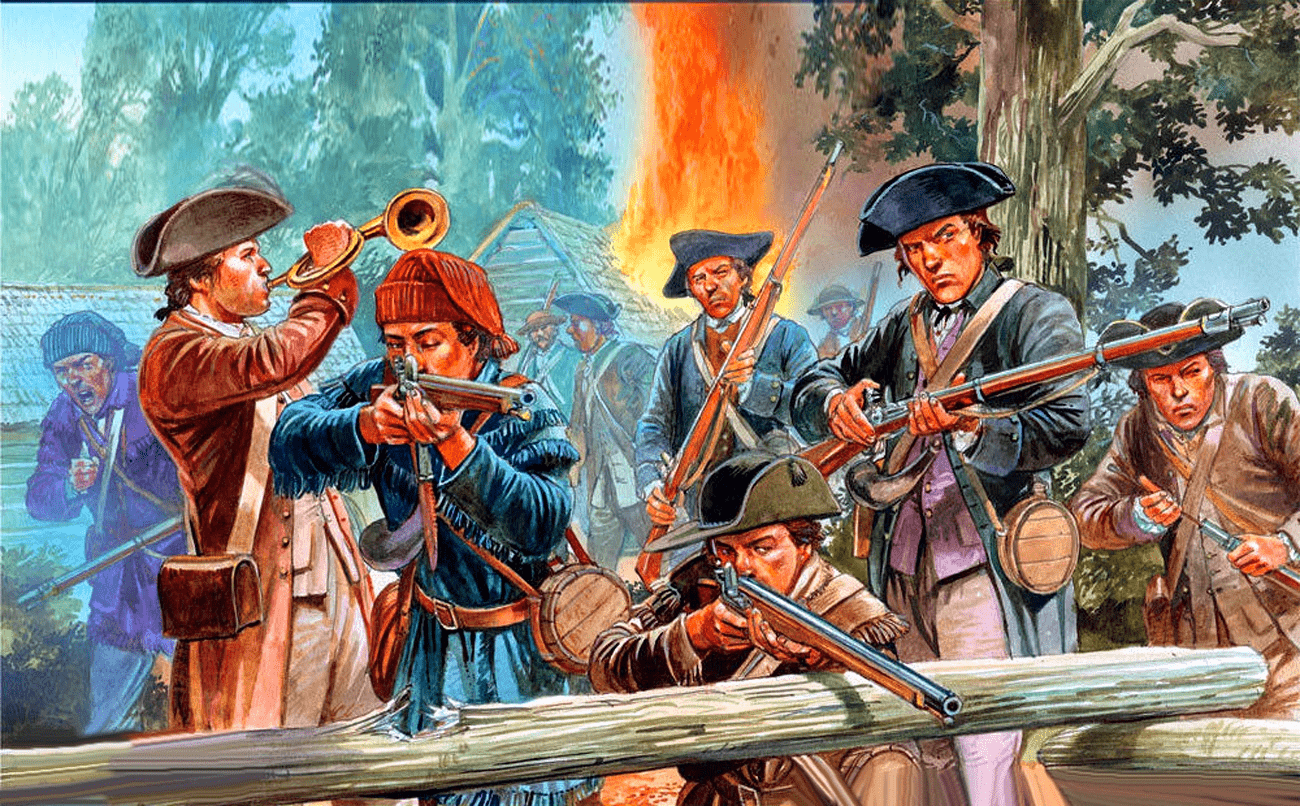

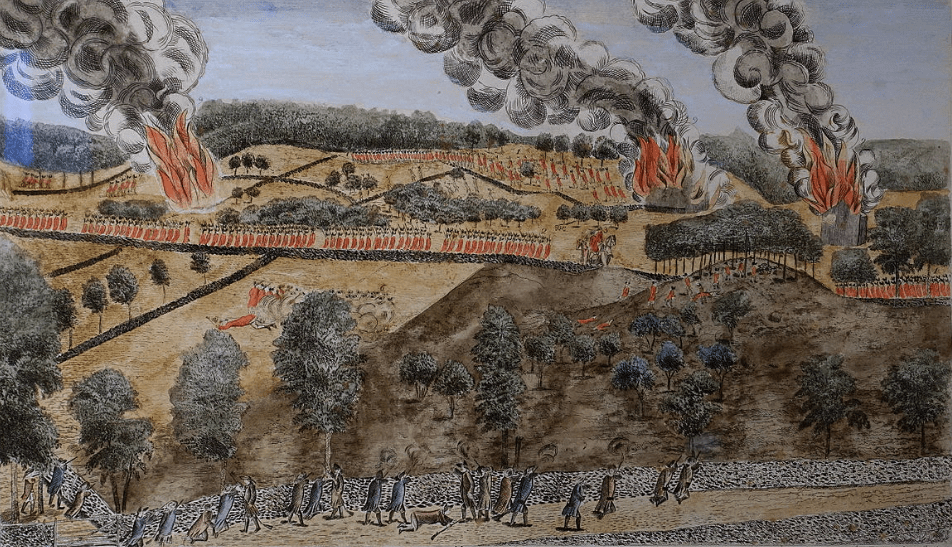

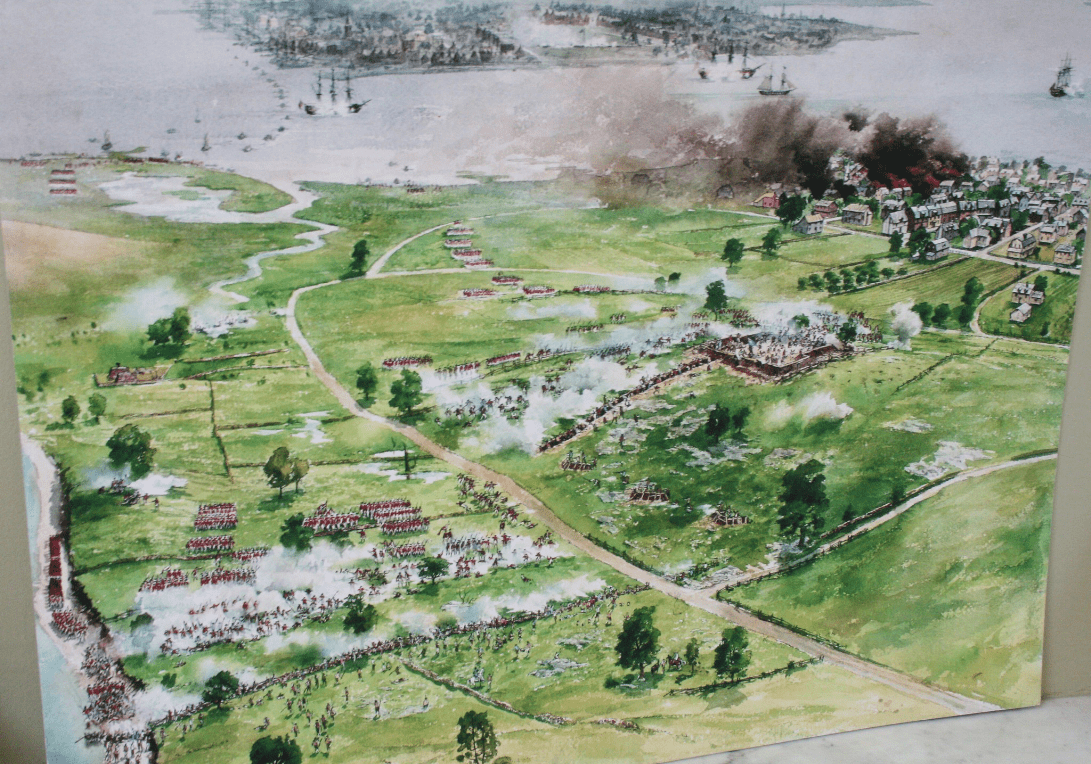

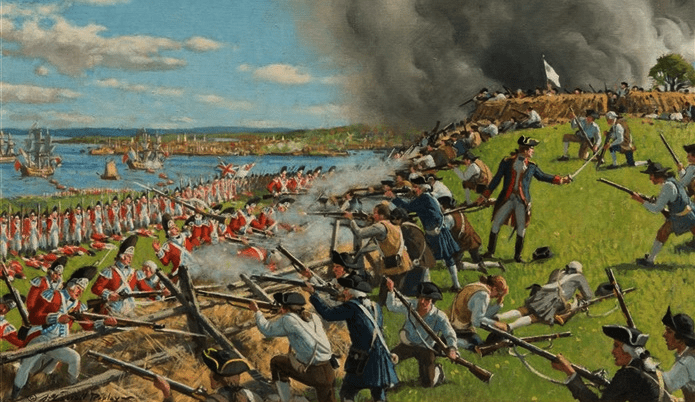

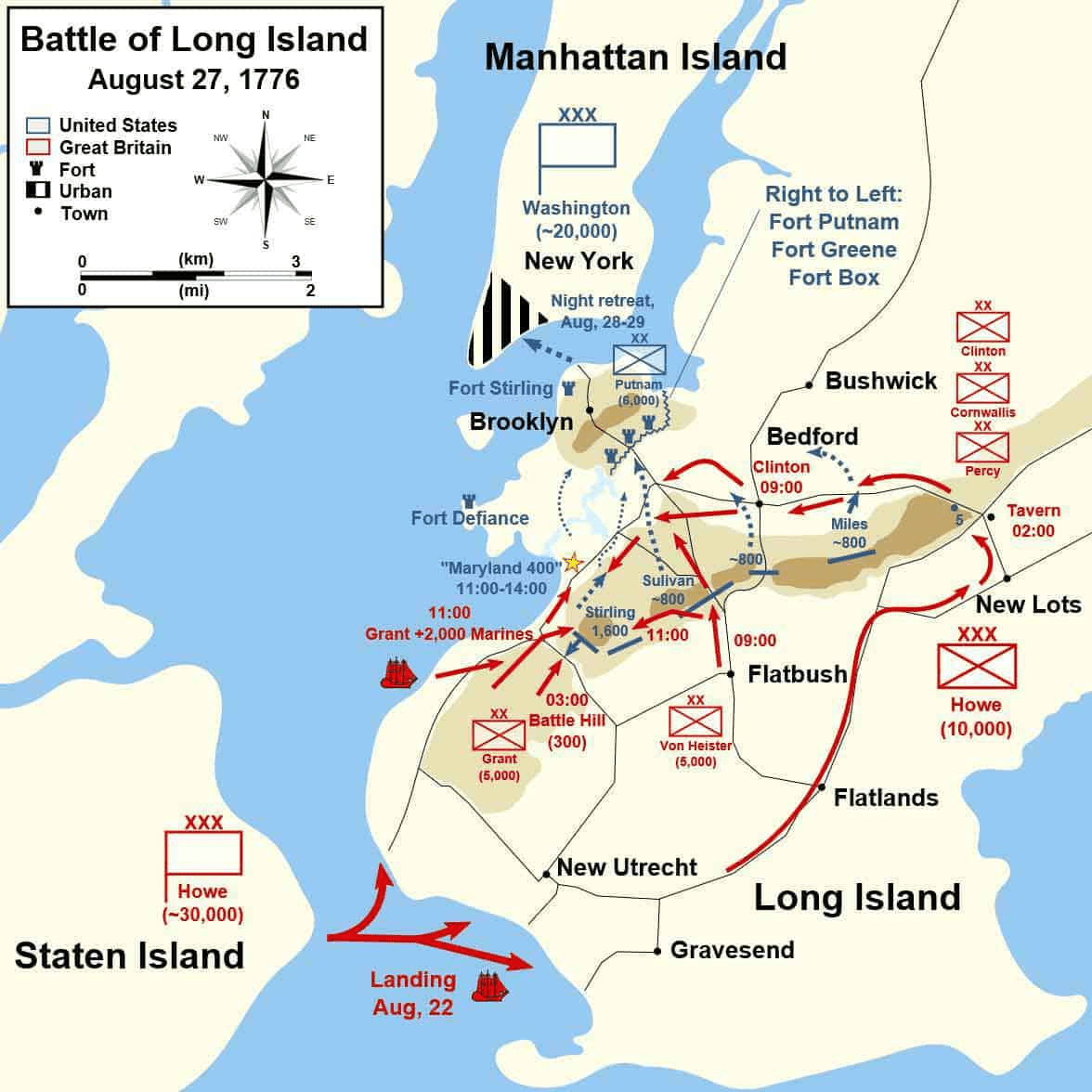

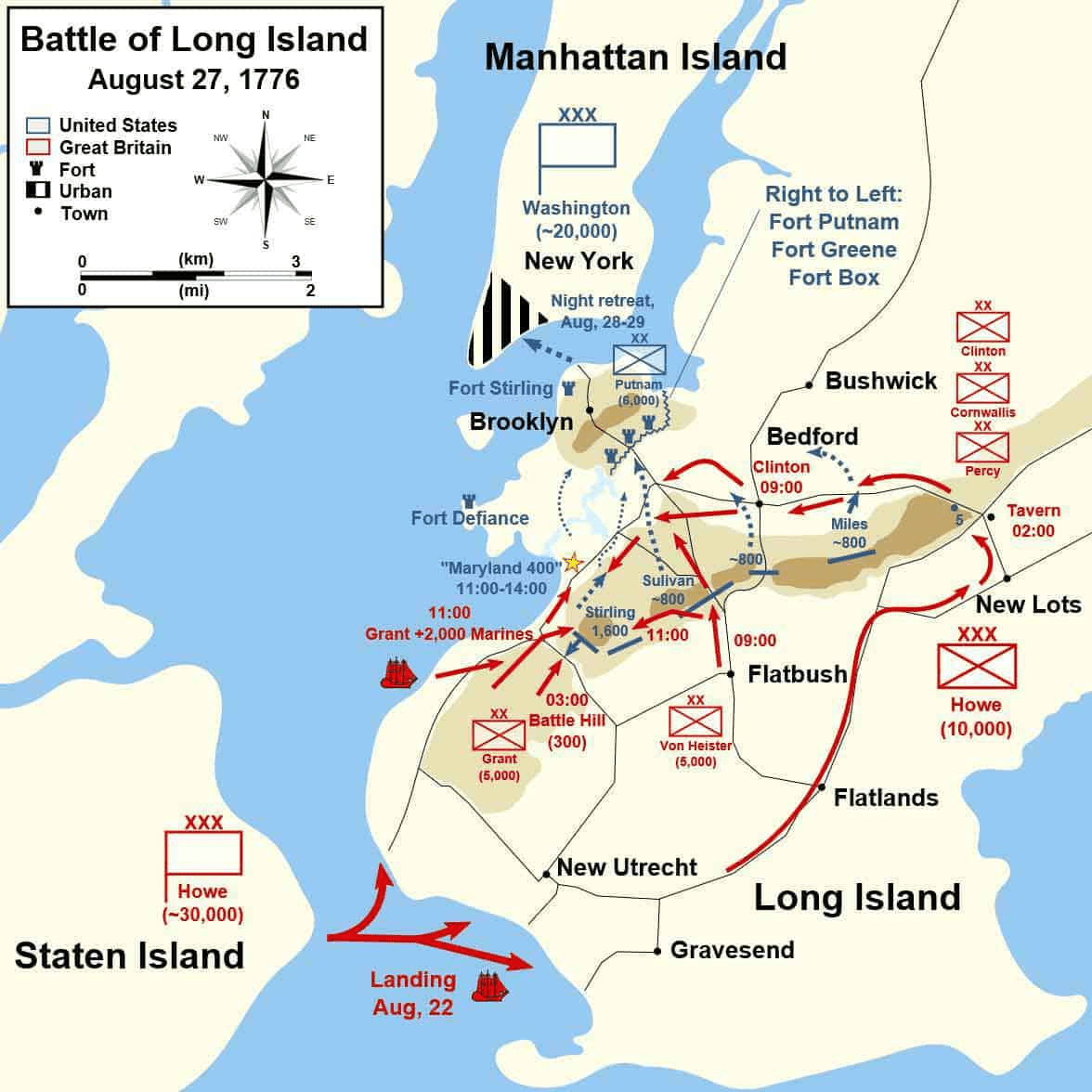

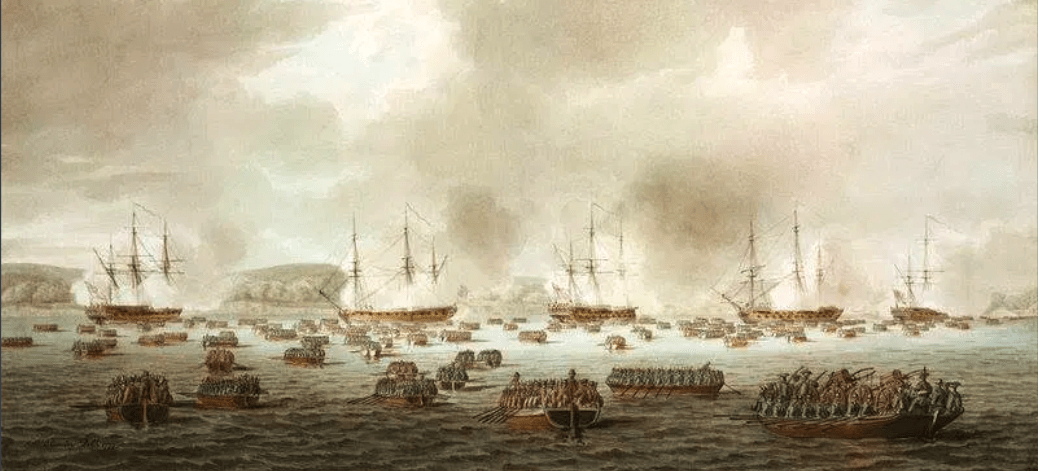

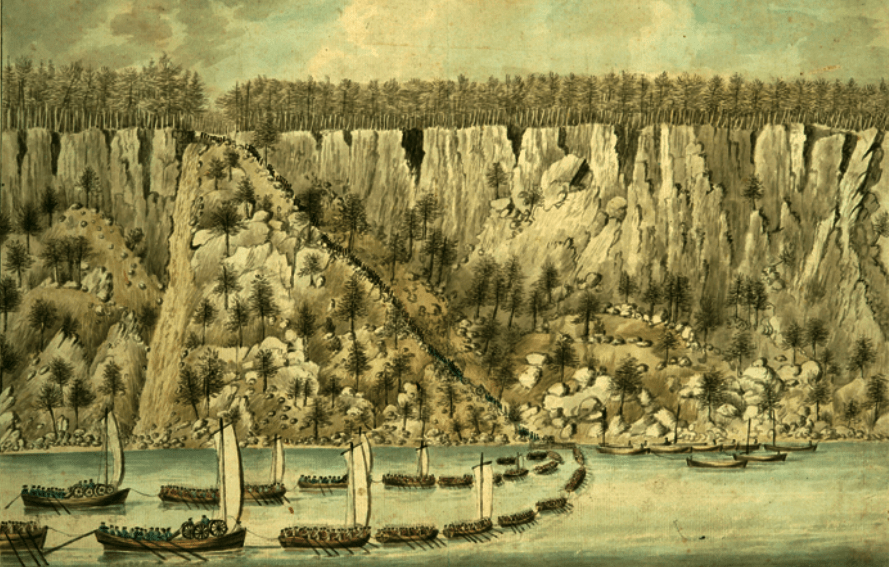

At 0510 hours on August 22, a vanguard of 4,000 British troops left Staten Island under the command of Clinton and Cornwallis to land on Long Island. At 08:00, the 4,000 landed unopposed on the shore of Gravesend Bay. Colonel Edward Hand's Pennsylvania Riflemen had been stationed on the shore, but they did not oppose the landings and fell back, killing cattle and burning farms along the way. By noon, 15,000 troops had landed on the shore along with 40 artillery pieces, when hundreds of loyalists arrived to greet the British troops. Cornwallis advanced with the vanguard, advancing 10 km to the island and setting up camp at the town of Flatbush. He was given orders not to advance any further. Washington received word of the landings the same day, but was told the number was about 9,000. This convinced him that it was the feint he had envisioned, and therefore he alone sent 1,500 more troops into Brooklyn, bringing the total number of troops on Long Island to 6,000. On August 24, Washington replaced Sullivan with Israel Putnam, who commanded troops on Long Island. Putnam arrived on Long Island the following day along with 6 BIs. Also on that day, British troops on Long Island received 5,000 Hessian reinforcements, bringing the total to 20,000. There was little fighting in the days immediately following the landing, although some minor skirmishes did take place with rifle-armed American sharpshooters driving out the British troops from time to time. The American plan was for Putnam to lead the defenses from Brooklyn Heights, while Sullivan and Stirling and their troops would be stationed on Guan Heights. Washington believed that by stationing men on the heights, heavy casualties could be inflicted on the British before the troops returned to the main defenses on Brooklyn Heights.

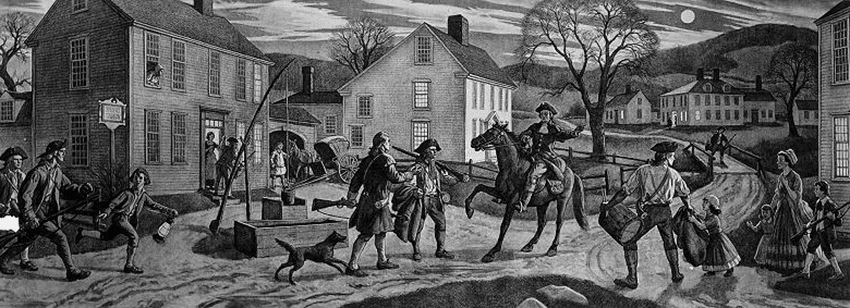

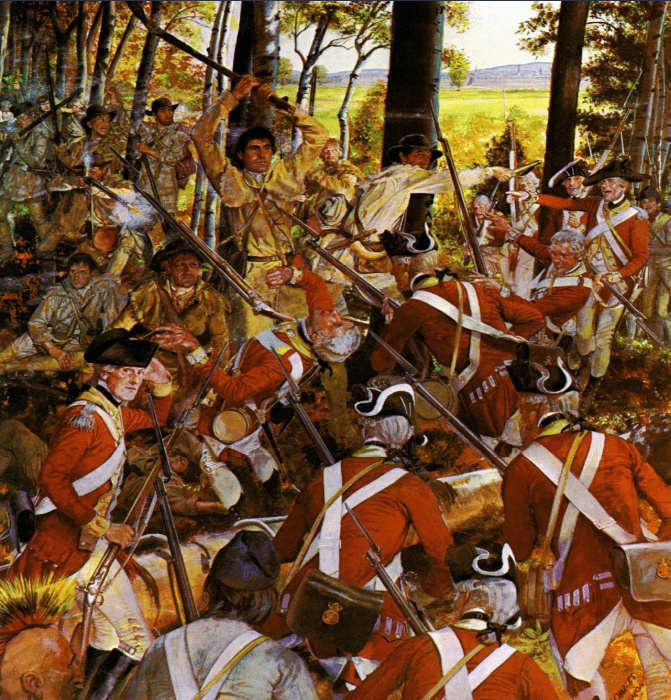

At 9:00 p.m. on August 26, the British began the movement. Nobody, except the commanders, knew of the plan. Clinton led the division of him. The column consisted of 10,000 men stretching over 3 km. Three loyal farmers led the column towards the Jamaica Pass. The British had left their fires burning to fool the Americans into believing that nothing had changed. The column headed northeast until it reached what later became the town of New Lots, when it headed directly north toward the heights. The column had not yet encountered any American troops when they reached Howard's Tavern, only a few hundred yards from Jamaica Pass. Saloonkeeper William Howard and his son William Jr. were forced to act as guides to show the British the way to the Rockaway, an old Indian trail that skirted the Jamaica Pass to the west. Five minutes after leaving the tavern, the five mounted militia officers stationed in the pass were captured without firing, as they thought the British were Americans. Clinton questioned the men and was told that they were the only troops guarding the pass. At dawn, the British crossed the pass and stopped so the troops could rest. At 09:00 a.m., two cannons were fired to signal the Hessian troops to begin their frontal assault on Sullivan's men deployed on the two hills flanking the pass, while Clinton's troops simultaneously outflanked the American positions. from the east. At approximately 11:00 p.m. on August 26, the first shots were fired at the Battle of Long Island near the Red Lion Tavern. American pickets from Pennsylvania's Samuel John Atlee Regiment fired on two British soldiers who were in a watermelon orchard near the tavern.

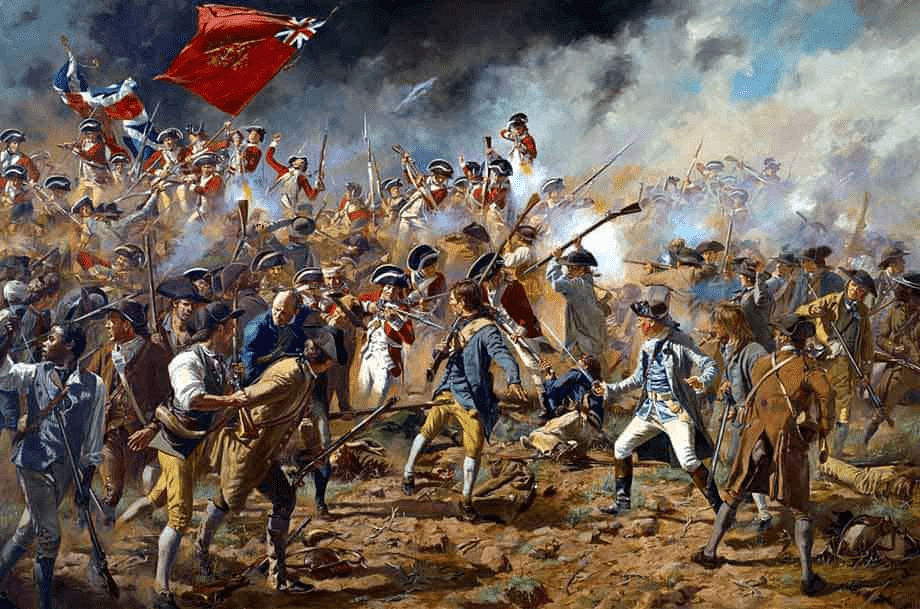

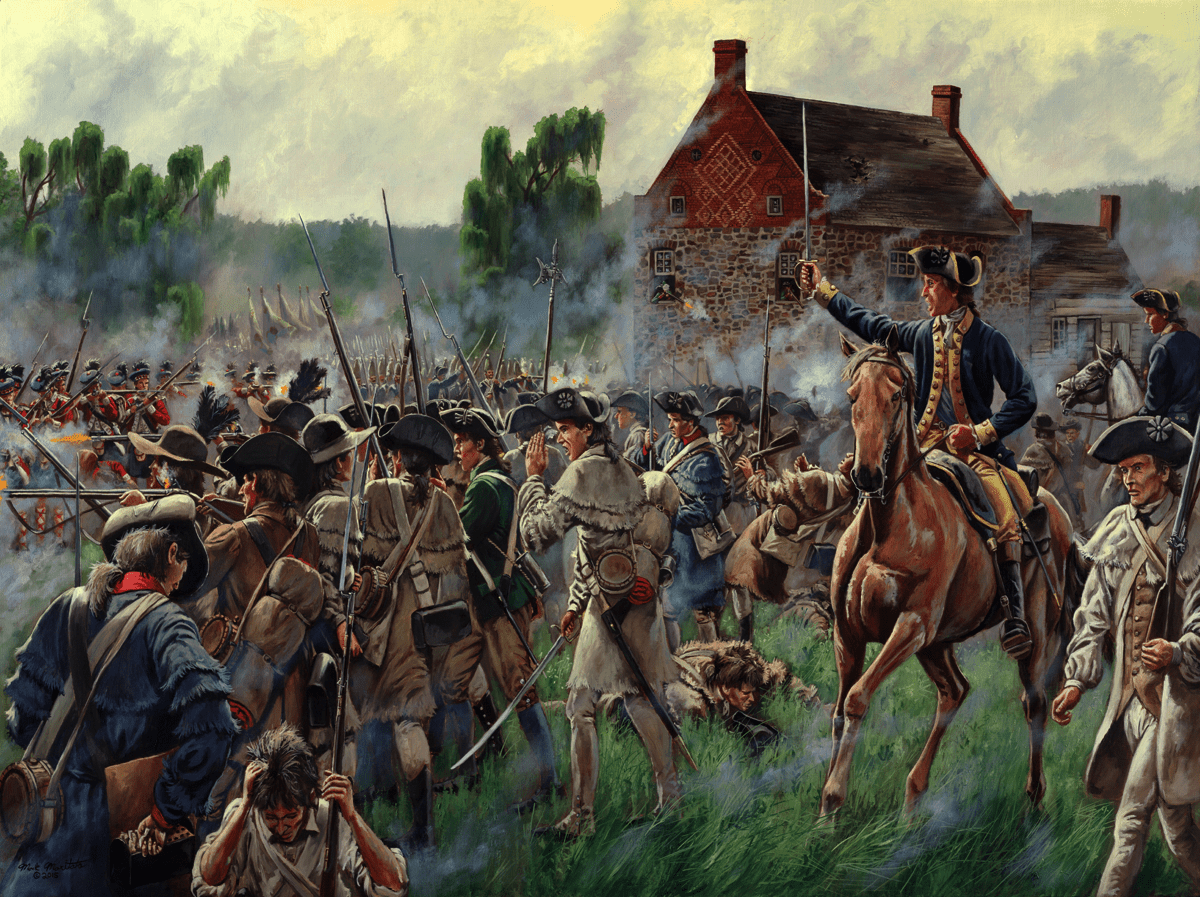

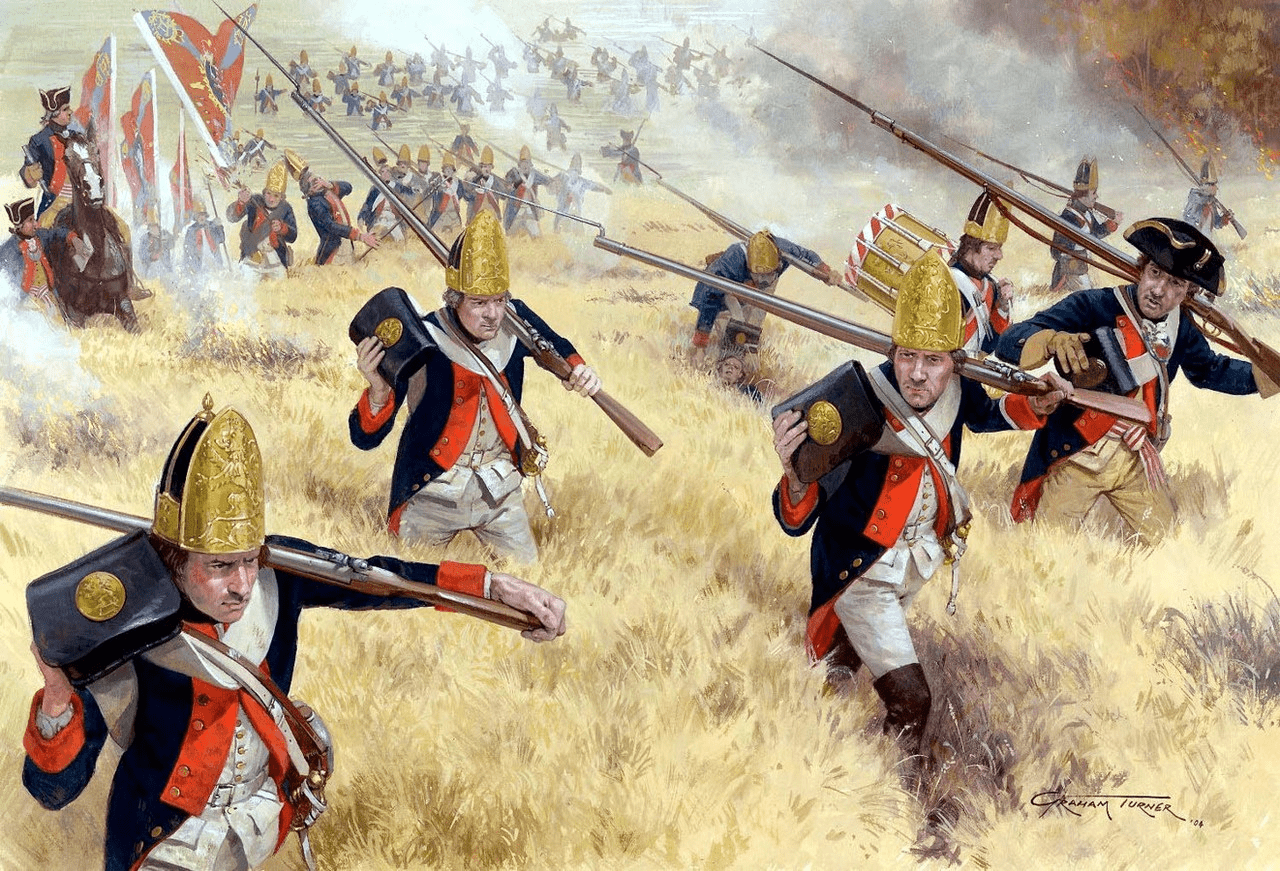

The fight for Guan Heights continues throughout the morning. British troops filter through Jamaica Pass and through several other American positions, eventually gaining control of the ridge. The bloodiest fights of the battle occur near Battle Pass, where Hessian mercenaries go toe-to-toe with the patriots. As the Americans fall back towards Brooklyn Heights, one contingent is nearly surrounded by the advancing British. About 400 Maryland soldiers, known as the "400 Marylanders", fight back to buy time for their comrades to escape. More than 250 Marylanders are killed while desperately fighting the British regiments, but the rest of the army manages to retreat safely. As night falls, Americans are huddled in Brooklyn Heights with the East River behind them. General Howe overrules subordinates who advocate a renewed assault, instead digging in and preparing to besiege Washington's army. Washington, however, does not consent to a siege and eventual surrender. In the dead of night, he coordinates a retreat across the river without losing a single life. When the British investigate the American lines, they find them empty. At the time, it was by far the largest battle ever fought in North America. If the Royal Navy is included, more than 40,000 men participated in the battle. Howe reported his losses of 59 killed, 268 wounded, and 31 missing. Hessian casualties were 5 killed and 26 wounded. The Americans suffered much greater losses. About 300 were killed and more than 1,000 captured. Only half of the prisoners survived. Kept on prison ships, then transferred to places like the Dutch Church in Media, they suffered from starvation and were denied medical care. In their weakened condition, many succumbed to smallpox. The British were stunned to discover that Washington and the army had escaped.

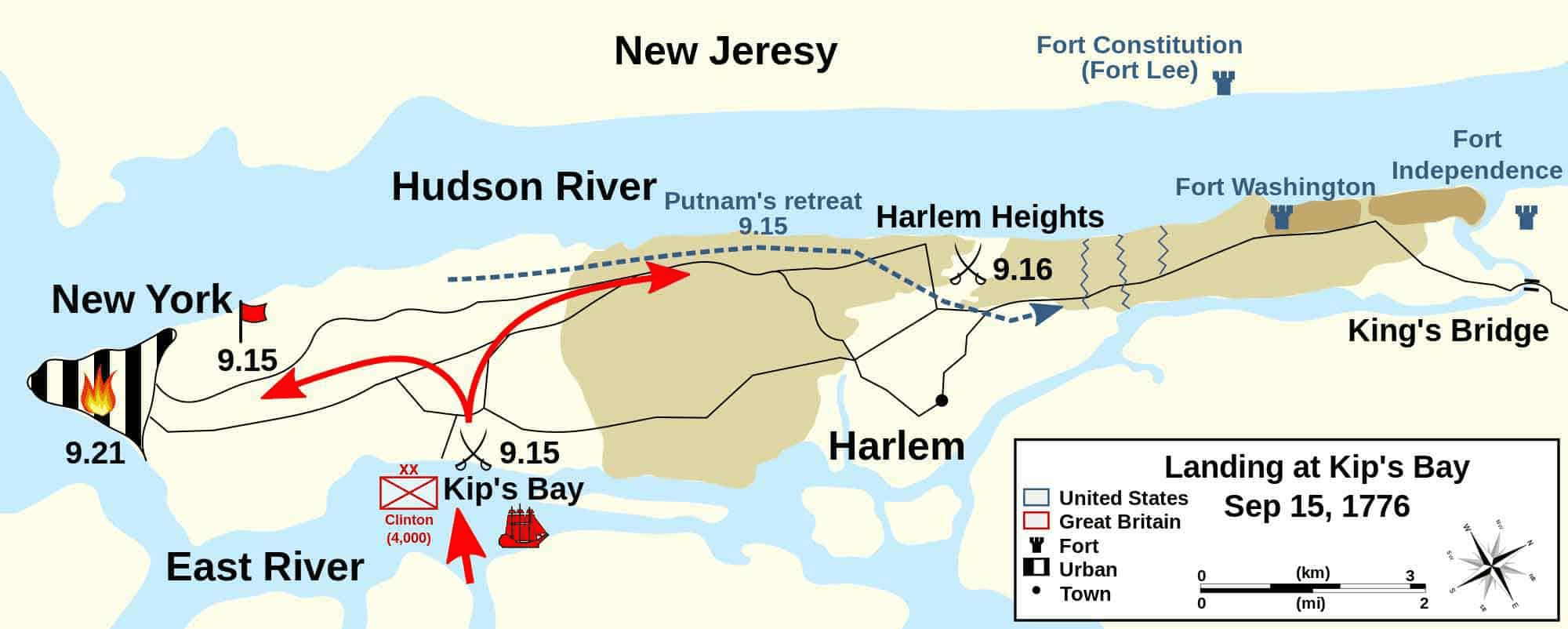

Later in the day, August 30, British troops occupied the American fortifications. When news of the battle reached London, it caused much festivities. Bells were rung throughout the city, candles were lit in windows, and King George III gave Howe the Order of the Bath. Washington's defeat revealed his shortcomings as a strategist who divided his forces, his inexperienced generals who misunderstood the situation, and his troops who fled in disorder at the first shots. However, his daring night retreat would be seen as one of his greatest military exploits. On September 10, British troops moved from Long Island to occupy Montresor Island, a small island at the mouth of the Harlem River. On September 11, the Congressional delegation arrived on Staten Island and met with Admiral Lord Howe for several hours. The meeting came to nothing, as Howe was not authorized to agree to terms insisted on by the congressional delegation. However, he postponed the impending British attack, allowing Washington more time to decide whether and where to engage the British force. On September 12, at a court martial, Washington and his generals made the decision to leave New York City. 4,000 Continentals under Israel Putnam remained to defend the city and lower Manhattan, while the main army moved north toward Harlem and King's Bridge. On September 13, the main British movement began when the ships of the line Roebuck and Phoenix, along with the frigates Orpheus and Carysfort, advanced up the East River and anchored in Bushwick Creek, carrying 148 guns in all and accompanied by 6 transport ships. of troops. By September 14, the Americans were rushing stores of ammunition and other materials, along with sick Americans, to Orangetown, New York.

Every available horse and cart was used in what Joseph Reed described as a "great military effort." Scouts reported movement in British Army camps, but Washington was still unsure where the British would attack from. By late afternoon, the bulk of the US Army had moved north towards King's Bridge and Harlem Heights, and Washington followed that night. Howe had originally planned a landing for September 13. He and General Henry Clinton disagreed on the point of attack, with Clinton arguing that a landing at the King's Bridge would cut off Washington once and for all. Howe originally wanted to make two landings, one at Kip Bay and one at Horn Hook, further north on the eastern seaboard. He took the latter option when the ship's pilots warned of the dangerous waters of Hell's Gate, where the Harlem River and the waters of Long Island Sound meet the East River. After delays due to unfavorable winds, the landing, directed to Kip's Bay, began on the morning of September 15, 1776. During the Battle of Kip's Bay, heavy advancing fire from British ships on the East River caused the flight of the inexperienced US militia guarding the landing zone. This made it possible for the British to land their troops unopposed. Skirmishes after the landings resulted in the British capture of some of those militia. The British maneuvers that followed the landing almost cut off the escape route of some Continental Army forces stationed further to the southeast of the island. The flight of the American troops was so rapid that General George Washington, who was attempting to rally them, was dangerously exposed near the British lines. The operation was a British victory and resulted in the withdrawal of the Continental Army to Harlem Heights, giving the British control of New York City in the lower half of the island.

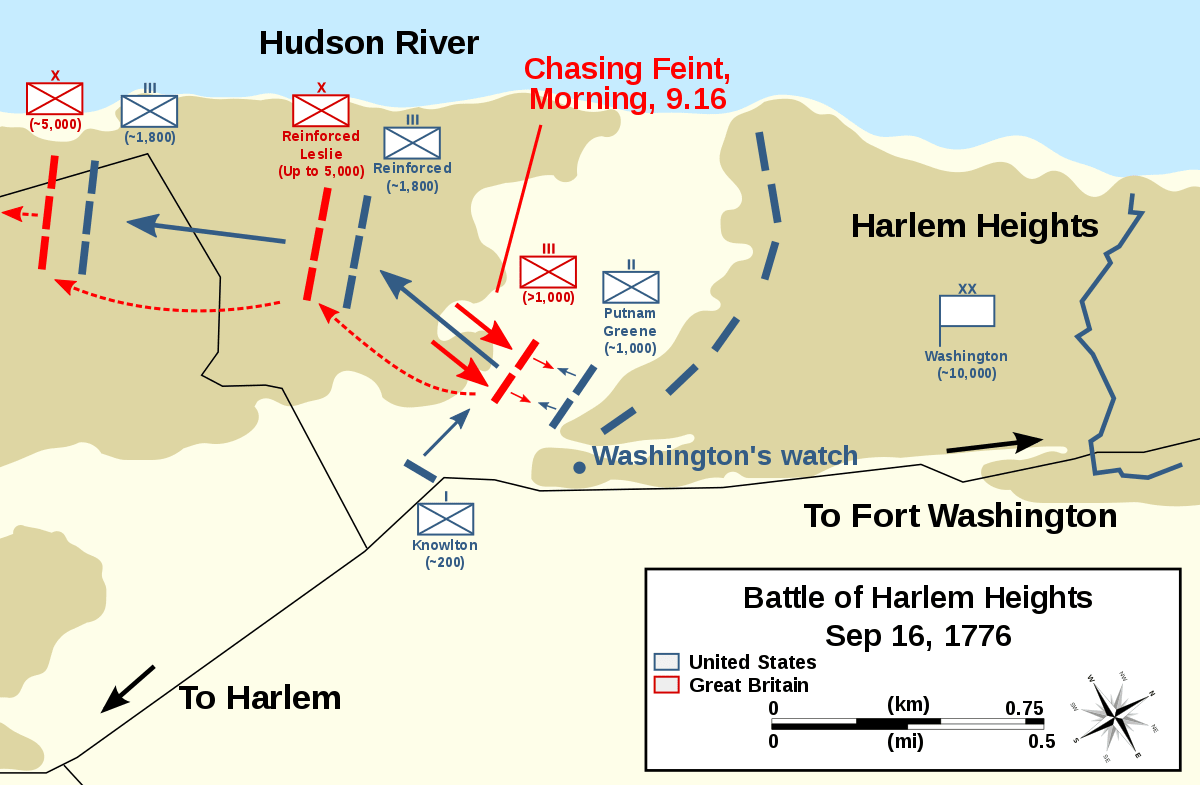

However, Washington established strong positions on Harlem Heights which he proved determined to defend in a fierce skirmish between the two armies the next day. General William Howe, unwilling to risk a costly frontal attack, did not attempt to advance further into the island for another two months. Washington was extremely angry with his troops' conduct, calling his actions "disgraceful" and "outrageous." The Connecticut militia was labeled cowardly and blamed for the defeat. Others, however, were more cautious, thinking that if the Connecticut militia had stayed behind to defend York Island under British gun fire and, in the face of overwhelming force, they would have been annihilated. On September 16, Washington was greatly concerned about the inability of his troops to deal with the British and Hessians in Howe's army. Step by step, the Americans were expelled from New York Island. Washington had only the northern plateau of the island, around the fortification of Fort Washington on the shore of the Hudson River. Washington dispatched a group of New England Rangers, under the command of Captain Thomas Knowlton, to monitor British movements south of his position. He descended from the northern plateau to a lowland area known as the Hollow Road and then to the next plateau. There his group of around 120 men met pickets of British light infantry and fire was exchanged. More British troops from the 42nd Highlander Black Watch or Black Watch Regiment emerged and the small group of Rangers were forced to withdraw in some haste, pursued by the British who blew fox horns as they pursued them.

Americans on the northern plateau are said to have been particularly incensed upon hearing the British use derisive fox-hunting calls. Washington ordered an advance force to draw the group of British further towards the plateau, while a second force moved around the British right flank and cut them off from the southern plateau and further reinforcements. The British took the bait and advanced towards the northern plateau while the Americans fell back before them. As they advanced south, the American flanking group encountered some British troops and gunfire broke out, warning the light infantry that they were in a dangerous position. The fighting spread north before Washington decided to send troops forward in two flanking maneuvers, one under Major Andrew Leitch and the other under Knowlton. A third force of Americans feinted to attack the British on their front. One of Howe's subordinates made a critical mistake during the fight. A fox horn was sounded before the fight ended. Fox hunters used a "Fox Horn" to signal to other hunters that the fox had given up and was ready to be killed. The American force heard the horn and all it did was motivate the men to fight even harder. Although the Americans attacked before the British were surrounded and Leitch and Knowlton were mortally wounded, the British found themselves attacked from three sides and began their retreat. Under persistent attack, the British withdrew to a field at Hollow Way. Fighting continued for an hour until the imminent arrival of more British forces. This caused Washington to call his troops back. The number of troops increased to nearly 5,000 on each side as the British were forced back.

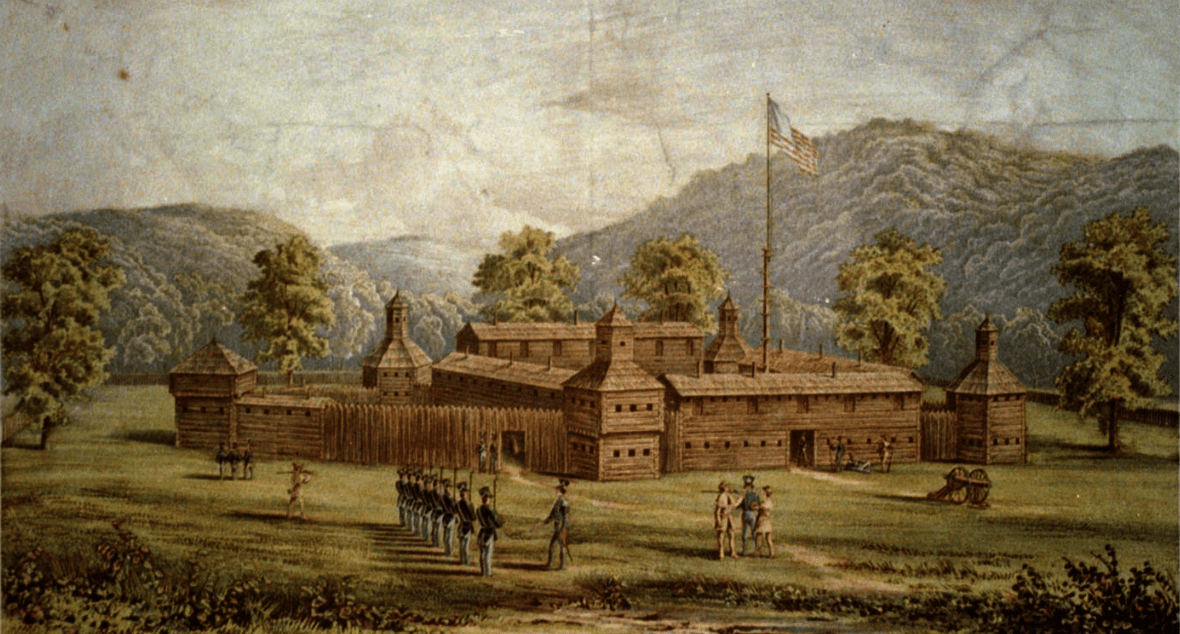

Washington called off the attack after 6 hours because the Americans were not ready for a general confrontation with the entire British army. The significance of this action to the Americans was that it was the Virginia militia, who had fled the day before, fighting steadily and effectively alongside the Northern rangers that went a long way toward restoring confidence in the American military. During the British advance on New York Island, one of Knowlton's American officers, Captain Nathan Hale of Coventry, Connecticut, was caught by the British in civilian clothes acting as a spy. Hale was hanged and said in his last words «I only regret, that I only have one life to lose for my country«. After the Battle of Long Island, the British Army forced the Americans off Manhattan Island. Howe chased Washington slowly out of New York City and into the countryside. Howe extended his own command in a line from New Rochelle in the south to the town of Scarsdale in the north. Howe and his conservative supporters had a stronghold in New York City. After Washington abandoned Manhattan Island, he deployed his force in a long defensive line in Westchester County, with the northern part in White Plains. White Plains was located 20 miles northeast of New York City. It was a rural and sparsely populated farming community. The terrain consisted of gently rolling hills through which the Bronx River valley ran. His goal was to escape the clutches of the British while evacuating tons of supplies before they could be captured by the superior British force. At the behest of the Continental Congress, Washington had to leave some 2,800 troops, commanded by Colonel Robert Magaw, to occupy Fort Washington and another 3,500 troops under Major General Nathanael Greene to defend the opposite shore at Fort Lee. Their mission was to disrupt and prevent the British fleet from moving upriver above the forts and into the Hudson River Valley.

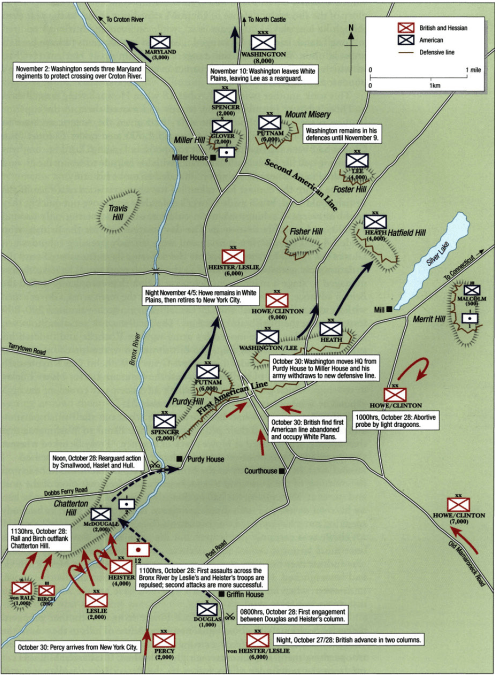

On October 22, Washington and his army arrive in White Plains. They joined his advance unit, which had started arriving the day before, and began fortifying the three surrounding hills. At White Plains, Washington spread out his army 3 miles wide, including the pass through the city. The right flank was commanded by Brigadier General William Heath, the center was commanded by Washington, and the right flank was commanded by Major General Israel Putnam. Howe was in New Rochelle, where he was in no hurry to move against Washington. This gave the Americans time to reach his new position safely. On October 23, some 8,000 Heissens, commanded by Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, arrived in New Rochelle and reinforced Howe's army. Howe decided to leave some 4,000 Hessians to garrison New Rochelle. On October 27, the British vanguard arrives at White Plains. Chatterson's Hill rose 180 feet above the plain and the top was gently rounded with steep, wooded slopes. The top of the hill was divided into cultivated fields by stone walls. It was located to the right of the American line, across the Bronx River. At the time, Washington had not strengthened this position. The double line front of the Washington conclave covered the city of White Plains. Looking south, the American line was anchored on the right (west) flank at Purdy Hill along the Bronx River and on the left beyond the city at Hatfield Hill near a large pond. The center was directly in front of the city. Beyond Washington's right, about half a mile across the river, was Chatterson's Hill. Initially, Washington did not perceive the hill as important enough to occupy. On the morning of October 28, the British entered Scarsdale and advanced on White Plains.

Howe received information that Washington had massed his army and deployed it in a large shallow crescent below the town, with the narrow Bronx River swollen protecting the American right flank. Howe's advance was formed into two columns, one British and one Hessian. Lieutenant General Henry Clinton commanded the British column and Major General Wilhelm von Heister commanded the Hessians. Washington ordered Brigadier General Joseph Spencer to take a detachment of 1,500 men and two guns to block the British on the plains between Chatterson's Hill and Scarsdale. Spencer had the first line manned by the Massachusetts militia and the second line was manned by the Delaware Continentals. At 9:30 a.m., once the delay force had made contact with the British, they returned and reported to Washington that the British were approaching in two columns along the East Chester Road. Once in White Plains, Howe spread out his army in an open area about a mile in front of the American line. Howe saw Chatterson's Hill and recognized that it was critical terrain. He planned the main attack on Chatterson's Hill while the rest of his army kept the rest of the American line busy. As Howe and his command consulted, the Hessian artillery on the left opened fire on the hilltop position on Chatterson's Hill, where they managed to drive the militia into a panicked retreat. The arrival of McDougall and his brigade helped to rally them and a defensive line was established, with the militia on the right and the Continentals arrayed along the brow of the hill. After the artillery bombardment, a detachment of 4,000 men was sent to attack the American position. First, Howe sent 3 Hessian regiments, commanded by Colonel Johann Rall, across the river, where they took up positions on some ridges about 1/2 mile from Chatterson's Hill. The rest of the attacking force then crossed a ford downriver and climbed the hill. Finally, the 17th Dragoons were sent out on a cavalry charge, the first cavalry charge of the war.

Rall threatened Spencer's left flank. The militia panicked and were soon routed, but the mainlanders put up a stiff resistance before being forced to make an orderly retreat. The Americans were forced across the river to Chatterson's Hill. With the British now close behind, Washington suddenly realized the critical nature of Chatterson's Hill and decided to strengthen it. He ordered around 1,600 troops, made up of Delaware Continentals and Maryland militia to help occupy the hill. This brought the total defensive force on the hill to around 2,500 soldiers. Major General Alexander McDougall assumed command of the hill force. After Spencer's detachment was driven off, Howe moved his army to the flat land below the high ground and facing the city within sight of Washington. Howe then divided his command and sent 8 regiments to attack the high ground of Chatterson's Hill. He also placed 20 guns under Chatterson's Hill and opened fire on the American positions. McDougall was only able to fire a couple of shots before being forced to abandon his guns. As the British artillery bombardment continued, British and Hessian troops fought their way under fire towards the Bronx River. They then crossed the river and fanned out to attack the hill. The British regiments attacked directly against the American positions while the Hessians attempted a flanking maneuver against the American right flank. The British were forced back with heavy casualties, but the Hessians took up a position beyond the American left flank, which was held by inexperienced militiamen from New York and Massachusetts. The fight lasted only a few minutes before the militia fled. The fleeing militia exposed the flank of the Delaware troops.

The appearance of the advancing Hessians confused the Delaware troops. Although many companies formed up and repulsed several Hessian attacks, the pressure against their front continued and supporting troops moved to the rear. Unable to maintain a defense, the rest of the Delaware troops were forced into an orderly retreat from the field. After the loss of Chatterson's Hill, Washington had no choice but to withdraw further north, beyond the Croton River, to Castle Hill. At 5:00 PM, the battle ended. Howe was content to hold on to Chatterson's Hill. The two armies remained where they were for two days, while Howe reinforced the position on Chatterton Hill and Washington organized his army to withdraw to the hills north of White Plains. With the arrival of additional Hessian and Waldeck troops under Lord Percy on October 30, Howe planned to move against the Americans the following day. However, heavy rain fell throughout the next day, and when Howe was finally ready to act, he awoke to find that Washington had eluded him again. On October 31, Washington withdrew his army into the northern foothills overnight, setting up camp near North Castle. Howe decided not to follow, instead trying unsuccessfully to draw Washington out. On November 1, the British advanced but found that Washington and his army were gone, having retreated to the hills north of White Plains. Howe decided not to follow the Americans and allowed them to withdraw safely to New Jersey. During the fighting in and around Manhattan, the US Army commanded by General George Washington, for whom the fort was named, was forced to withdraw north, leaving Forts Washington and Fort Lee isolated. After defeating the Continental Army at the Battle of White Plains, British Army forces, commanded by Lieutenant General William Howe, planned to capture Fort Washington, the last American stronghold in Manhattan.

Washington had considered abandoning Fort Washington, but was convinced by Greene, who believed that the fort could be held and that it was vital to do so. Greene argued that keeping the fort would keep communications across the river open and might deter the British from attacking New Jersey. Magaw and Putnam agreed with Greene. Washington gave in to Greene and did not leave the fort. On November 4, Howe ordered his army south toward Dobbs Ferry. Rather than pursue US forces in the highlands, and possibly motivated by intelligence gained from Demont's defection, Howe had decided to attack Fort Washington. Washington responded by dividing his army. Seven thousand soldiers were to remain east of the Hudson River under Major General Charles Lee to prevent a British invasion of New England; General William Heath, with 3,000 men, was to protect the Hudson Highlands to prevent any British advance north; and Washington, with 2,000 men, would go to Fort Lee. On November 13, Washington and his army arrived at Fort Lee. Howe's plan of attack was to assault the fort from three directions while a fourth force feigned; by then it had received reinforcements and was garrisoned by 3,000 men. Hessian troops under Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen would attack the fort from the north, Percy would lead a brigade of Hessians and several British battalions from the south, and General Charles Cornwallis with the 33rd Regiment of Foot and General Brigadier Edward Mathew. with light infantry they were to attack from the east. The feint was to be from the 42nd Highlanders, landing on the east side of Manhattan, south of the fort. On November 15, before attacking the fort, Howe sent Lieutenant Colonel James Patterson under a flag of truce to deliver a message that if the fort did not surrender, the entire garrison would be killed. Magaw said the Patriots would defend the fort to the "last end".

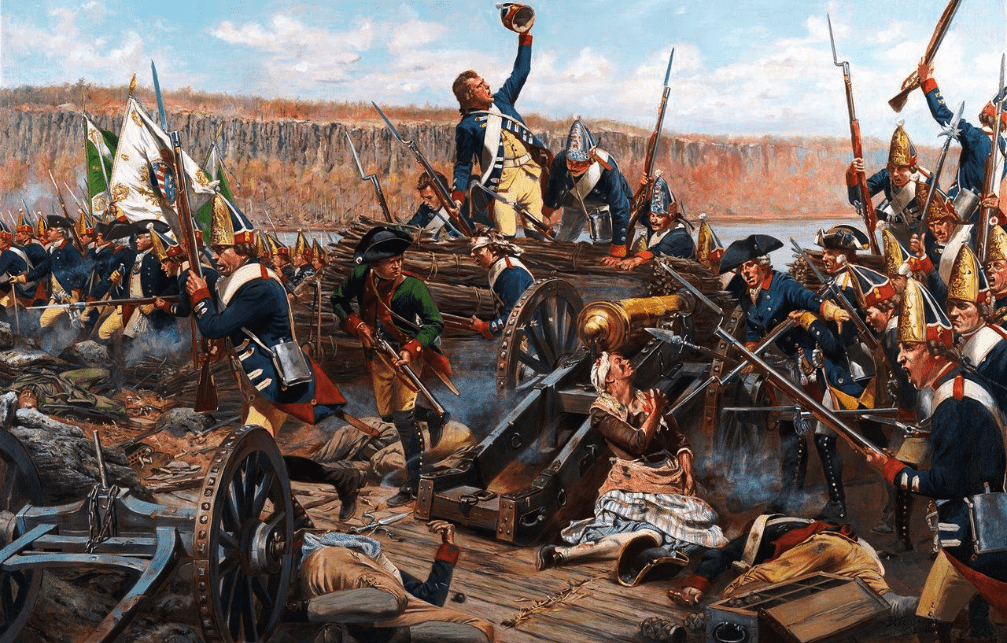

On November 16, before dawn, the British and Hessian troops withdrew. General Knyphausen and his troops crossed the Harlem River in flatboats and landed in Manhattan. The boatmen then turned downriver to ferry Mateo's troops across the river. However, due to the tide, they were unable to get close enough to shore to cross the British troops. Therefore, Knyphausen's troops were forced to stop their advance and wait until Mathew could cross. Around 7:00 a.m. At 15:00 am, the Hessian guns opened fire on the American battery on Laurel Hill and the British frigate HMS Pearl began firing on the American entrenchments. Also, south of the fort, Percy had his artillery open fire on the fort. Percy's artillery took aim at Magaw's guns. At noon, Knyphausen and his Hessians restarted their advance. As soon as the tide was high enough, Mathew and his troops, accompanied by Howe, crossed the Harlem River. They landed under heavy fire from American artillery on the Manhattan shoreline. British troops charged up the hillside and dispersed the Americans until they reached a redoubt held by some companies of Pennsylvania volunteers. After a short fight, the Americans turned and ran toward the fort. North of the fort, the Hessian right, commanded by Colonel Johann Rall, moved up the steep slope south of Spuyten Duyvil Creek with almost no American resistance. The Hessians began to bring up their artillery. At this point the main body of Hessians began to advance up the Post Road, which ran between Laurel Hill and the hill Rall was on. The Hessians crossed swampy land and as they approached the wooded hillside near the fort, they were fired upon by 250 riflemen from the Maryland and Virginia Regiment of Rifles, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Moses Rawlings.

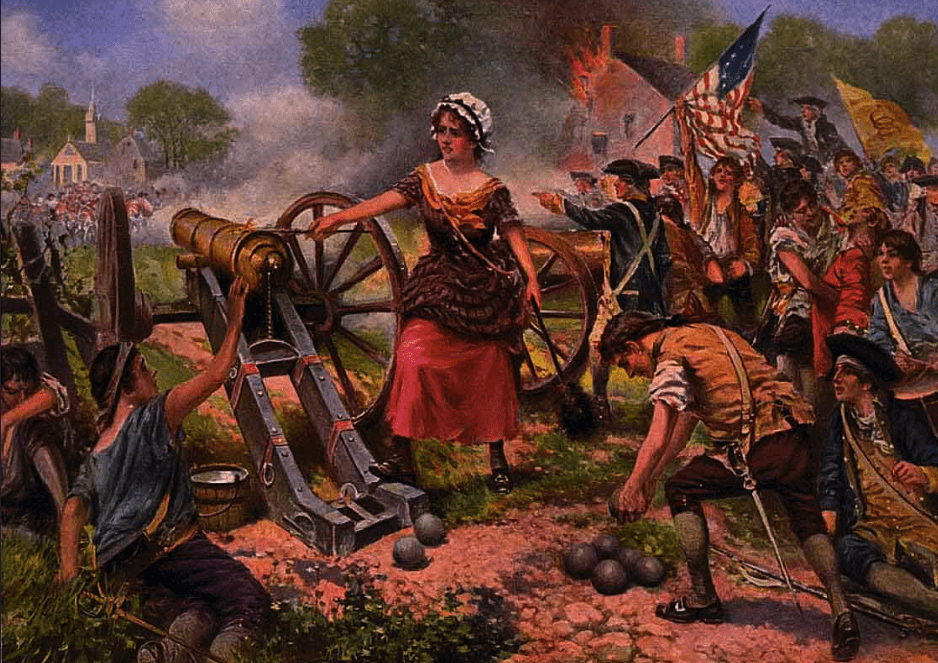

Rawlings's men hid behind rocks and trees and ran from place to place to shoot at the Hessians as they tried to advance through the fallen trees and rocks. The Hessians' first and second charges were repulsed by Rawlings's riflemen. John Corbin was in charge of firing a small cannon on top of a hill. During an assault by the Hessians, Corbin was killed, leaving his cannon without a crew. Margaret Corbin had been with her husband on the battlefield the entire time and, after witnessing his death, she immediately took her place in the cannon and continued firing until her arm, chest and jaw were hit by enemy fire, thus becoming the first known female combatant in the American Revolution. At about the same time, to the south, Percy advanced with about 3,000 men. Percy advanced in two columns with his brigade of Hessians on the left and Percy himself on the right. Some 200 yards from the American lines, Percy halted the advance, waiting for Stirling's feint to come through. Facing Percy was Alexander Graydon and his company. Graydon's superior was Lambert Cadwalader, Magaw's second-in-command, who was in charge of holding the three defensive lines south of Fort Washington. After hearing that there was a shore landing to his rear, Cadwalader sent 50 men to oppose it. The 50 men ran into the feint of the 700-man Colonel Stirling's 42nd Foot. Where Stirling landed turned out to be the least defended area of the American defenses, and when Cadwalader heard how many men were there, he sent another 100 men to reinforce the 50 he had sent earlier. The British landing parties spread out, finding a way through the rough terrain to the landing site. The Americans took up a position on top of a hill and began firing on the British troops still crossing the river, killing or wounding 80 men.

British troops charged the American position, scattering them. Hearing the gunshots, Percy ordered his troops to continue their advance. British artillery fire forced Graydon in the first defensive line back to the second line, where Washington, Greene, Putnam and Hugh Mercer stood. The four were encouraged to leave Manhattan, which they did immediately, sailing across the river to Fort Lee. Magaw realized that Cadwalader was in danger of being surrounded and sent orders for him to withdraw towards the fort. Cadwalader's force was pursued by Percy's troops at the same time that the troops opposing Stirling's landing were also pursued towards the fort. Stirling's troops, landed in Cadwalader's rear, halted, believing there were troops in the entrenchments. Some of the retreating Americans engaged Stirling, giving most of the rest of the American troops ample time to escape. With the collapse of Magaw's outer lines to the south and east of the fort, the general retreat to the perceived safety of the fort took place. To the south, the third defensive line had never been completed, so Cadwalader had nowhere left to retreat to except the fort. To the north, the Riflemen under Rawlings were still holding out, but just barely, since there were fewer Riflemen than before and since the increased firing had jammed some of the men's weapons, some of the men were forced to leave. push rocks down the hill in the attacking Hessians. The American battery at Fort Washington was silenced by the Pearl. By this time the rifle fire had almost ceased and the Hessians advanced slowly up the hill and engaged the Americans in hand-to-hand fighting. Overpowering the Americans, the Hessians reached the top of the hill and rushed the redoubt with a bayonet charge, quickly capturing it.

Washington, watching the battle from across the river, sent a note to Magaw asking him to hold out until nightfall, thinking the troops might be evacuated during the night. By this time, the Hessians had taken the ground between the fort and the Hudson River. Rall had the honor of requesting the American surrender by Knyphausen. Rall sent Captain Hohenstein, who spoke English and French, under a flag of truce to call for the fort's surrender. Hohenstein met with Cadwalader, and Cadwalader requested that Magaw have four hours to consult with his officers. Hohenstein denied the request and gave the Americans half an hour to decide. While Magaw was consulting with his officers, Washington's messenger, Captain John Gooch, arrived just before the fort was completely surrounded, with Washington's request to hold out until nightfall. Magaw attempted to obtain more favorable terms for his men, who would only be allowed to keep his belongings, but failed. at 3:00 p.m. m., the Germans had reached Fort Washington from the north and the British were in sight to the east and south. Realizing that standing up now would create a bloodbath within the crowded fort, Magaw announced his decision to capitulate the fort. at 4:00 p.m. m., the American flag was lowered at the fort, replaced by the British flag. The loss of all their weapons and equipment was especially damaging. Fort Lee was now untenable, and Washington began hauling the ammunition out of the fort. After the Hessians entered the fort, American officers attempted to placate the Hessian commander, Captain von Malmburg, who was in charge of the surrender. As they emerged from the fort, the Hessians stripped the American troops of their baggage and went so far as to murder some of them. His officers intervened to prevent further injury or death.

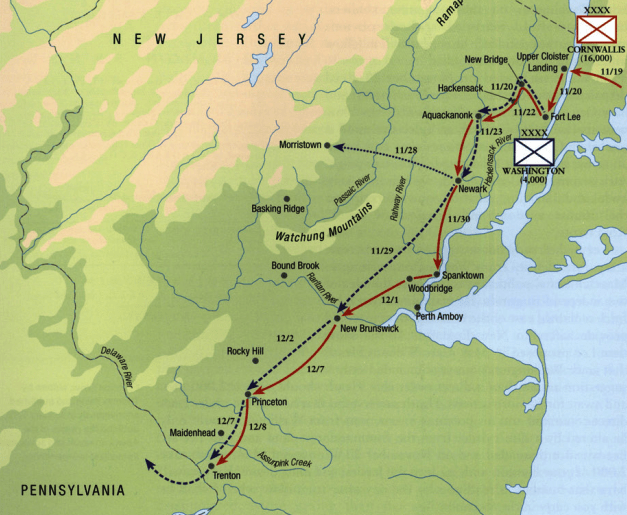

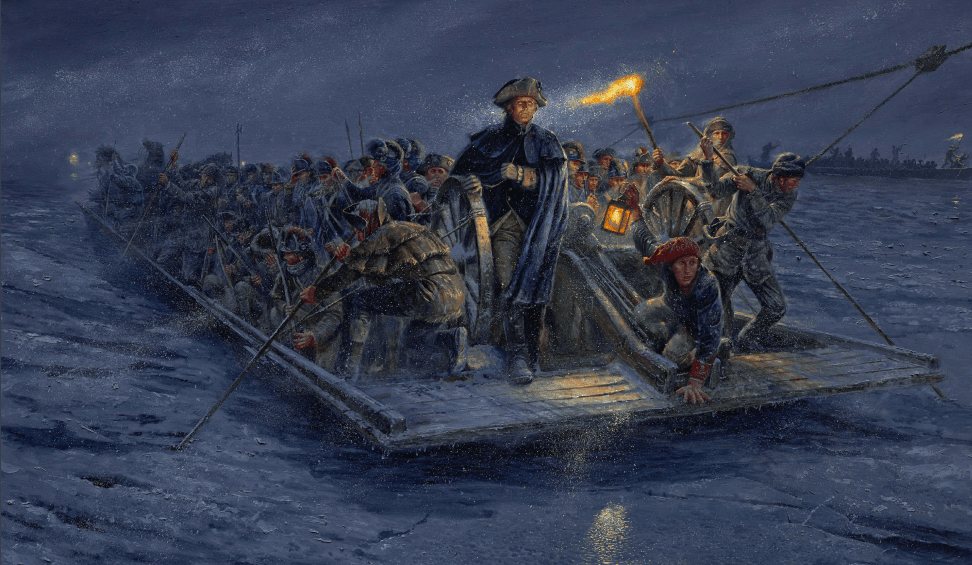

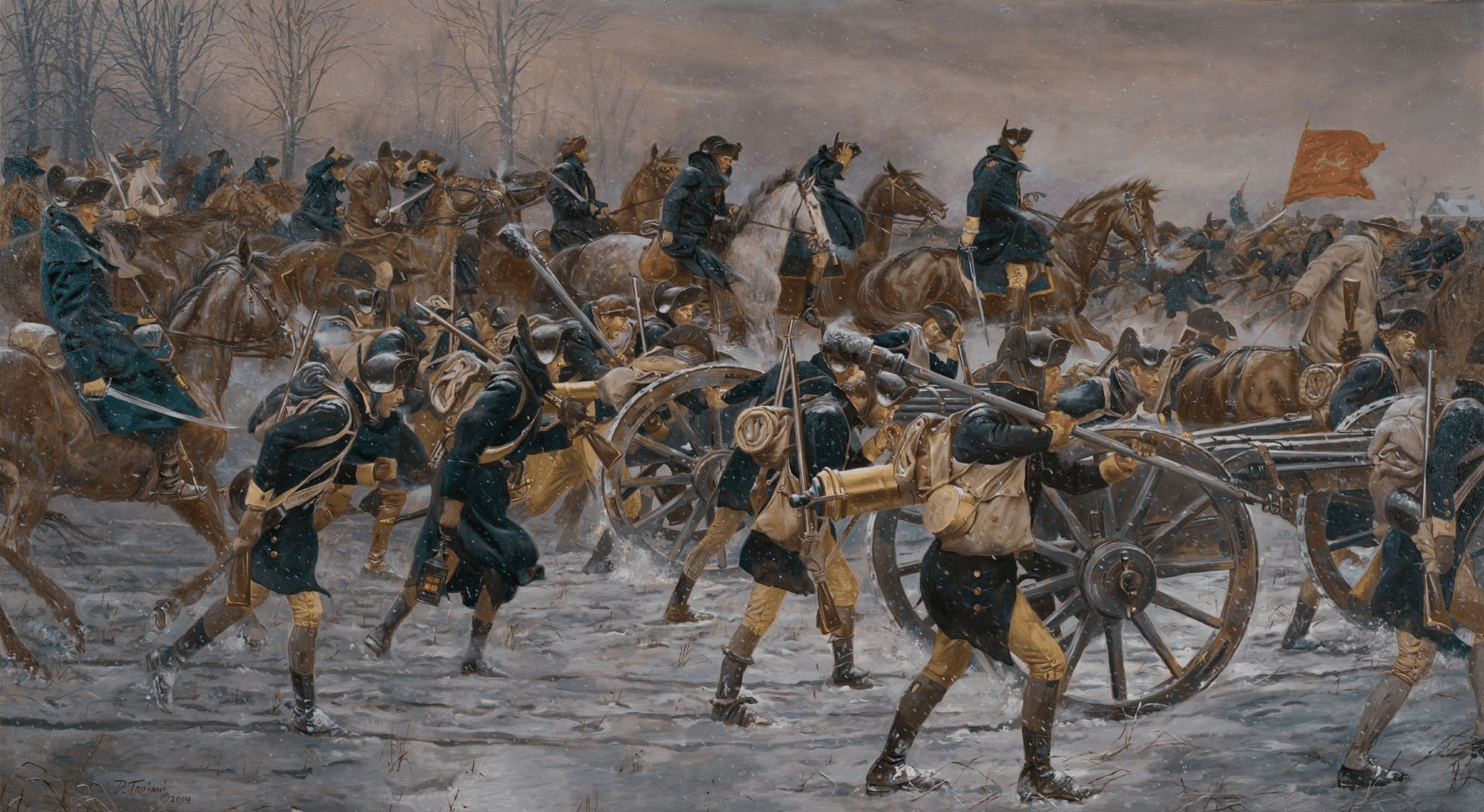

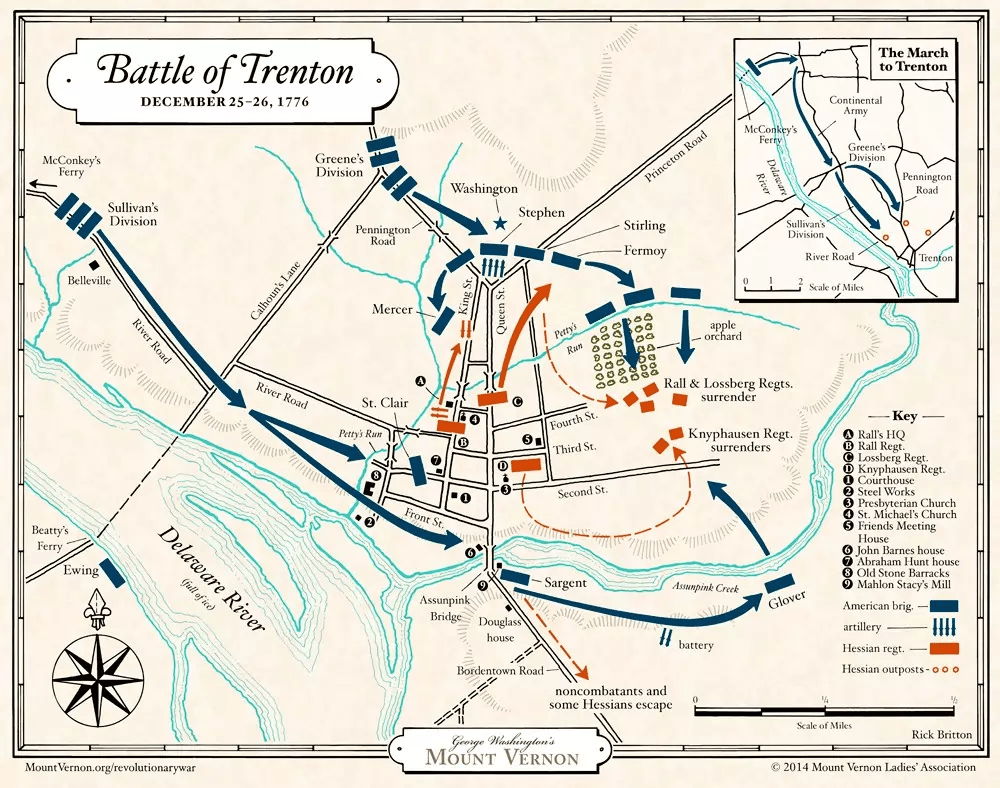

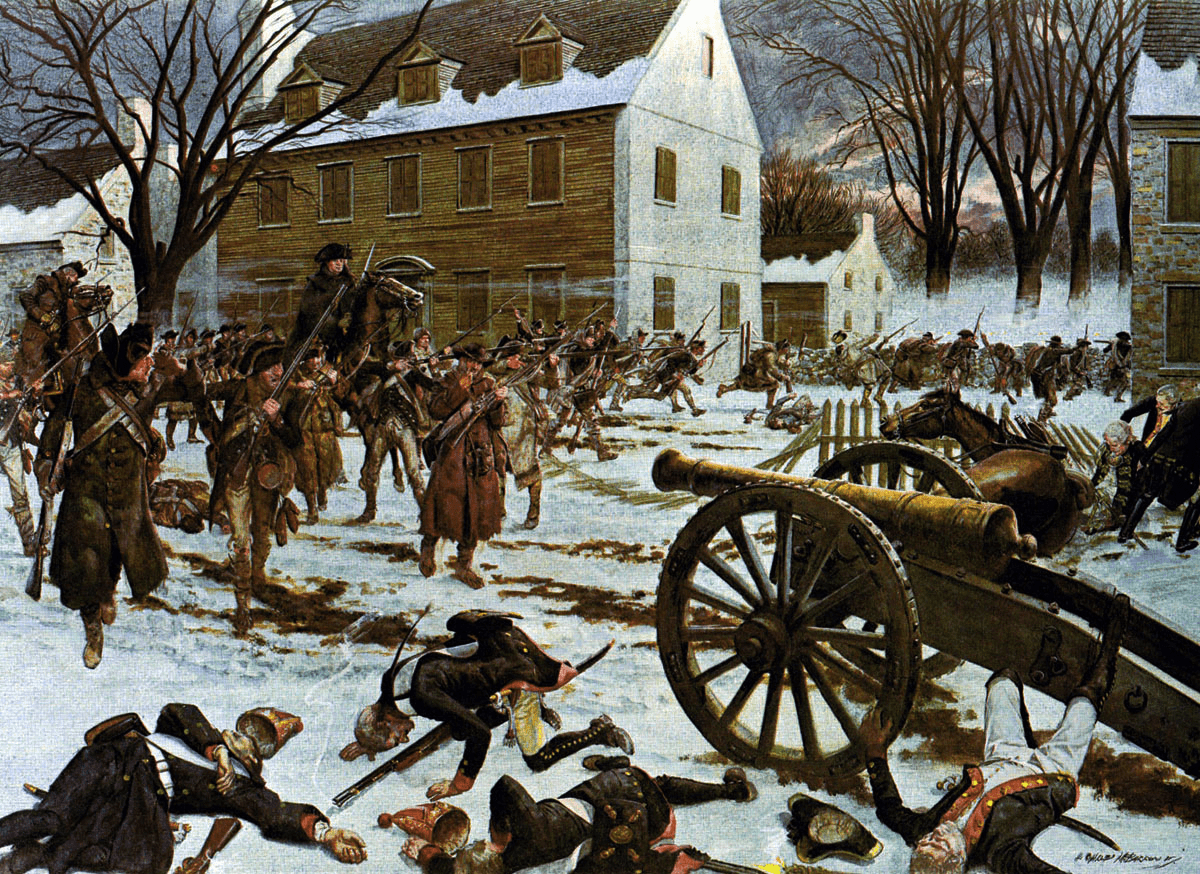

The British captured 34 guns, two howitzers, along with many tents, blankets, tools, and lots of ammunition. Under the usual treatment of prisoners of war during the Revolutionary War, only 800 survived their captivity to be released 18 months later in a prisoner exchange; nearly three-quarters of the prisoners died. Three days after the fall of Fort Washington, the Patriots abandoned Fort Lee. Washington and the army withdrew through New Jersey and crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania northwest of Trenton, pursued to New Brunswick, New Jersey by British forces.