Paladín Wulfen

Kicked

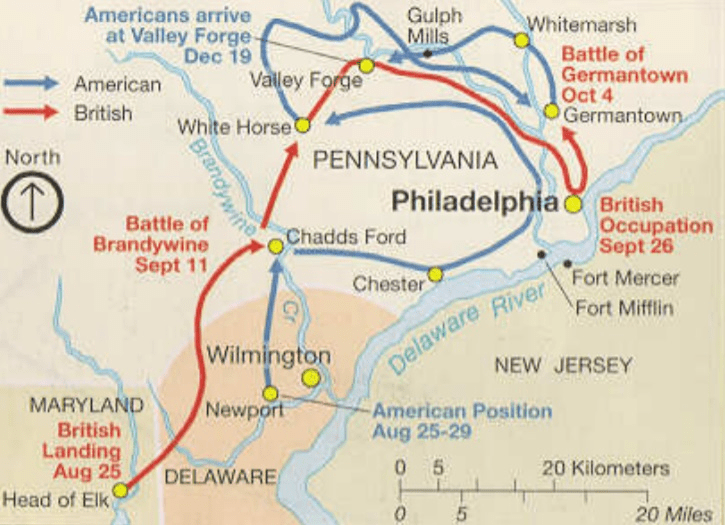

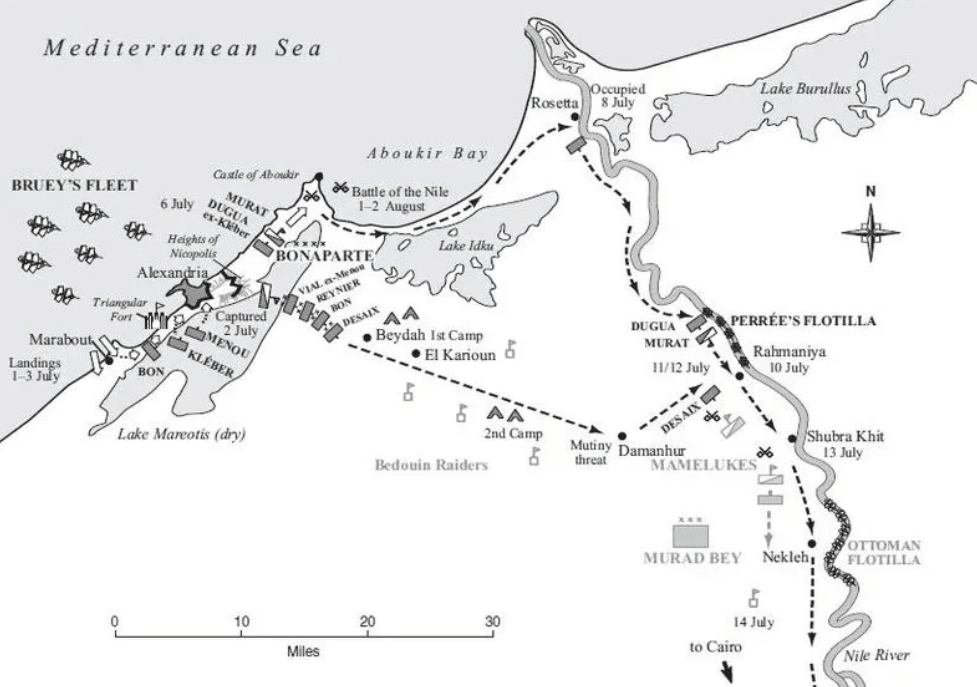

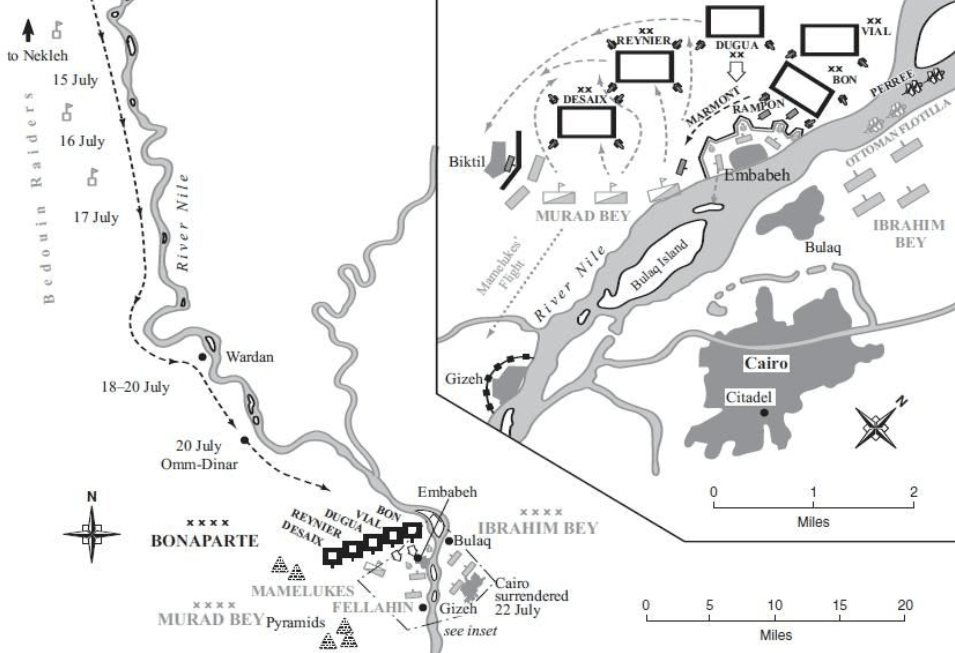

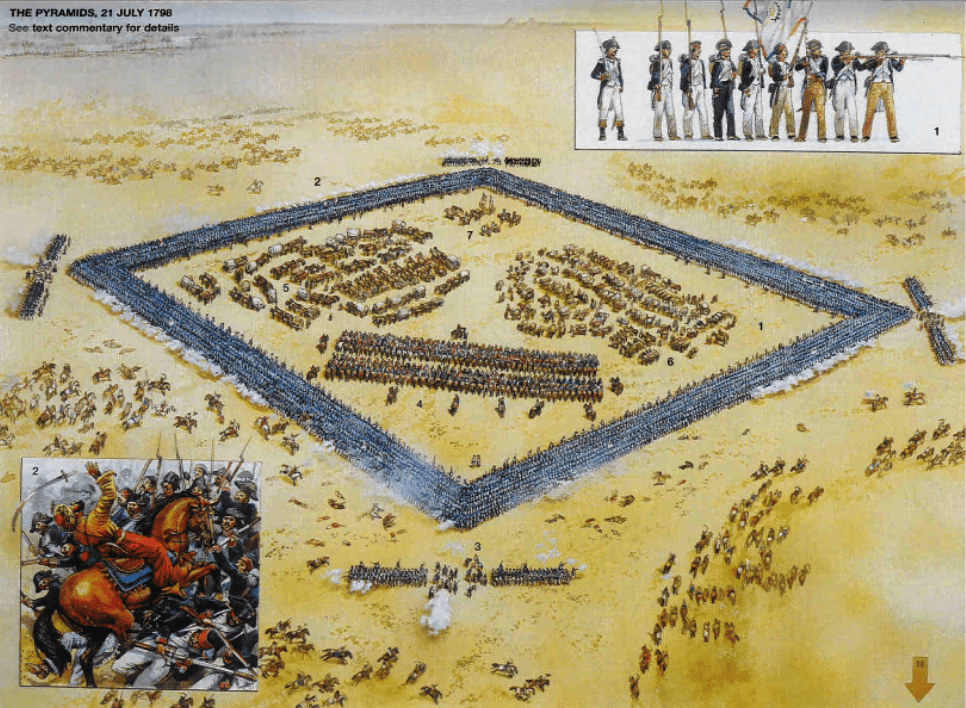

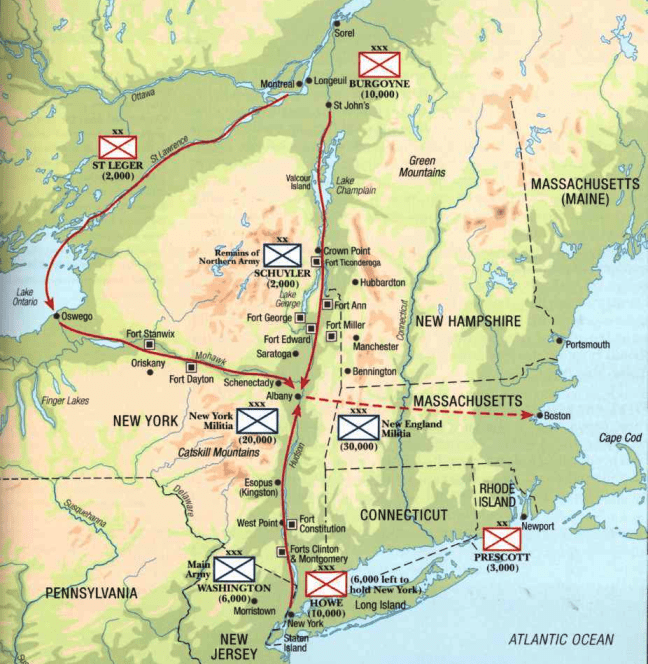

By the end of 1776, it was apparent to many in England that the pacification of New England was very difficult due to the high concentration of Patriots. London decided to isolate New England and concentrate on the central and southern regions where Loyalists were supposed to gather. In December 1776, TG John Burgoyne met with Lord Germain, the British secretary of state for the colonies and the government official responsible for administering the war, to establish a strategy for 1777. There were two main armies in North America to operate the General Guy with Carleton's army in Quebec and the army of General William Howe, who had driven George Washington's army out of New York City. It was decided to split the rebel territories with an attack from the north and another from the south and both forces would meet at Albany, cutting off the rebels. Lieutenant General Burgoyne, seeking to command a major force, proposed to isolate New England by invading from Quebec to New York. This had already been attempted by General Carleton in 1776, although he had stopped due to the lateness of the season. Carleton had been heavily criticized in London for failing to take advantage of the American withdrawal from Quebec. This, combined with General Henry Clinton's failed attempt to capture Charleston, South Carolina, put Burgoyne in a good position to gain command of the 1777 northern campaign. Burgoyne's invasion plan from Quebec had two components: would lead the main force of about 8,000 men south of Montreal along Lake Champlain and the Hudson River Valley, while a second column of about 2,000 men (which Barry Saint Leger was chosen to lead), would move from Lake Ontario east up the Mohawk River Valley on a strategic bypass. Both expeditions would converge at Albany, where they would be joined by troops from Howe's army, advancing up the Hudson River.

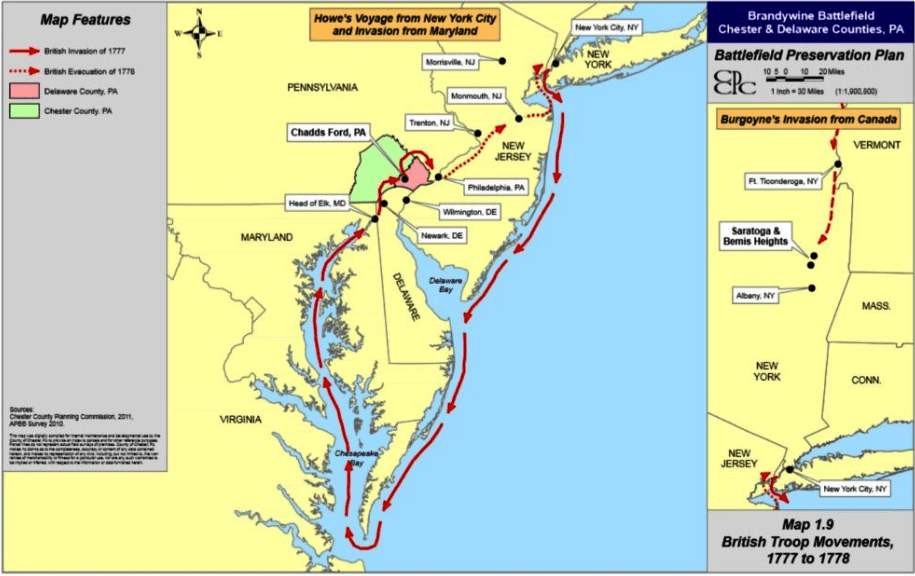

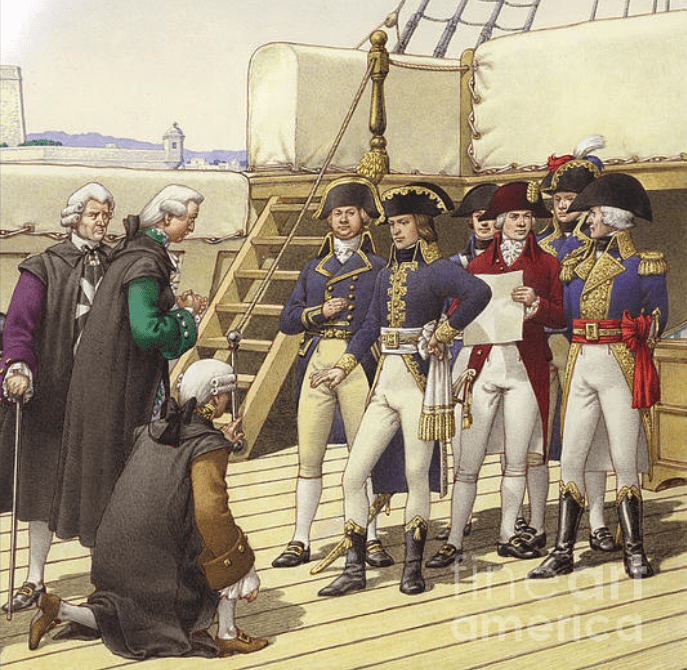

Control of the Lake Champlain–Lake George–Hudson River route from Canada to New York City would isolate New England from the rest of the American colonies. The last part of Burgoyne's proposal, Howe's advance up the Hudson River from New York City, proved to be the most controversial part of the campaign. Germain approved of Burgoyne's plan after receiving Howe's letter detailing his proposed offense against Philadelphia. It is also unclear whether Germain, Howe, and Burgoyne had the same expectations about the degree to which Howe should support the invasion of Quebec. What is clear is that Germain left his generals too free or without a clearly defined general strategy. In March 1777, Germain had approved Howe's expedition to Philadelphia and included no express orders for Howe to go to Albany. However, Howe did not receive this last letter until after he had left New York for the Chesapeake. To attack Philadelphia Howe could move overland through New Jersey or by sea through Delaware Bay, both options would have kept him in a position to assist Burgoyne if needed. The final route he would take would be across the Chesapeake Bay, which would be very time consuming and left him totally unable to help Burgoyne as Germain had envisioned. The decision was so difficult to understand that Howe's most hostile critics accused him of deliberate treason. Burgoyne returned to Quebec on May 6, 1777, with a letter from Lord Germain that laid out the plan but lacked some details. This produced another of the command conflicts that plagued the British during the war. Lieutenant General Burgoyne was technically superior to Major General Carleton, but Carleton was still the governor of Quebec. Germain's instructions to Burgoyne and Carleton had specifically limited Carleton's role in the operations in Quebec.

Control of the Lake Champlain–Lake George–Hudson River route from Canada to New York City would isolate New England from the rest of the American colonies. The last part of Burgoyne's proposal, Howe's advance up the Hudson River from New York City, proved to be the most controversial part of the campaign. Germain approved of Burgoyne's plan after receiving Howe's letter detailing his proposed offense against Philadelphia. It is also unclear whether Germain, Howe, and Burgoyne had the same expectations about the degree to which Howe should support the invasion of Quebec. What is clear is that Germain left his generals too free or without a clearly defined general strategy. In March 1777, Germain had approved Howe's expedition to Philadelphia and included no express orders for Howe to go to Albany. However, Howe did not receive this last letter until after he had left New York for the Chesapeake. To attack Philadelphia Howe could move overland through New Jersey or by sea through Delaware Bay, both options would have kept him in a position to assist Burgoyne if needed. The final route he would take would be across the Chesapeake Bay, which would be very time consuming and left him totally unable to help Burgoyne as Germain had envisioned. The decision was so difficult to understand that Howe's most hostile critics accused him of deliberate treason. Burgoyne returned to Quebec on May 6, 1777, with a letter from Lord Germain that laid out the plan but lacked some details. This produced another of the command conflicts that plagued the British during the war. Lieutenant General Burgoyne was technically superior to Major General Carleton, but Carleton was still the governor of Quebec. Germain's instructions to Burgoyne and Carleton had specifically limited Carleton's role in the operations in Quebec.

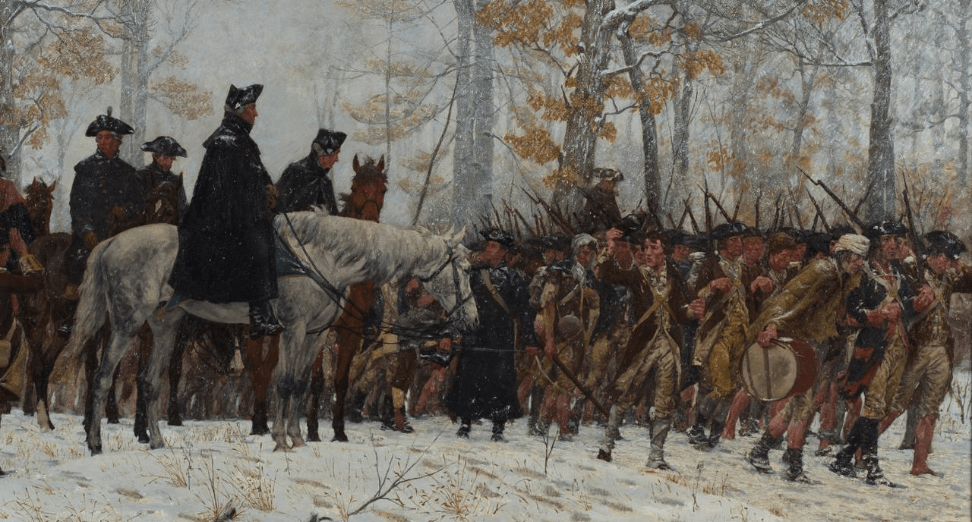

This slight against Carleton, combined with Carleton's failure to obtain an expedition from command, led to his resignation later in 1777, and his refusal to supply troops from the Quebec RIs to garrison the forts at Crown Point and Ticonderoga after being captured. George Washington, whose army was encamped in Morristown, New Jersey, did not have a good idea of British plans for 1777. The main question on the minds of Washington and his generals Horatio Gates and Philip Schuyler, who were both in turn responsible of the Northern Department of the Continental Army and its defense of the Hudson River, was of Howe's army movements in New York. They had no significant knowledge of what was being planned for the British forces in Quebec, despite Burgoyne's complaints that everyone in Montreal knew what he was planning, even though the plan had been published in a local newspaper. . The three generals disagreed on what Burgoyne's most likely move would be, with Congress also expressing the opinion that Burgoyne's army would probably move to New York by sea. Partly as a result of this indecision, and the fact that he would be cut off from his supply lines if Howe headed north, garrisons at Fort Ticonderoga and elsewhere in the Mohawk and Hudson river valleys did not increase significantly. Schuyler took the step in April 1777 to send a large Regiment under Colonel Peter Gansevoort to rehabilitate Fort Stanwix in the upper Mohawk Valley as a step in the defense against British moves in that area. Washington also ordered 4 Regiments to be raised at Peekskill, New York, which could head north or south in response to British moves. American troops were stationed throughout the New York theater in June 1777.

About 1,500 troops (including Colonel Gansevoort's) were at outposts along the Mohawk River; some 3,000 troops were in the Hudson River uplands under General Israel Putnam, and Schuyler commanded about 4,000 troops (including local militia and troops at Ticonderoga under Saint-Clair). The bulk of Burgoyne's army had arrived in Quebec in the spring of 1776. In addition to the British regulars, the troops in Quebec included several RIs from the German principalities of Hesse-Kassel, Hesse-Hanau, and Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel under the command of the Baron Friedrich Adolph Riedesel, comprised the Prinz Ludwig Regiment and the RIs of Specht, Rhetz, Riedesel, Prinz Frederich, Erbprinz and Breyman's jäger. Of these regular forces, 200 British and about 400 German regulars were assigned to the San Leger Mohawk Valley Expedition, and about 3,500 men remained in Quebec to protect the province. The remaining forces were assigned to Burgoyne for the campaign to Albany. The regular forces were supposed to be reinforced by up to 2,000 militia raised in Quebec. In June, Carleton had managed to raise only three companies. Burgoyne had also expected as many as 1,000 Indians to support the expedition. About 500 joined between Montreal and Crown Point. Burgoyne's army was beset by transportation difficulties before leaving Quebec, something neither Burgoyne nor Carleton apparently anticipated. As the expedition expected to travel primarily over water, there were few wagons, horses, and other draft animals available to move the large amount of equipment and supplies on the land portions of the route. Only in early June did Carleton issue orders to procure enough wagons to move the army. Consequently, the carts were poorly constructed of green wood, and the teams were driven by civilians who were at high risk of desertion.

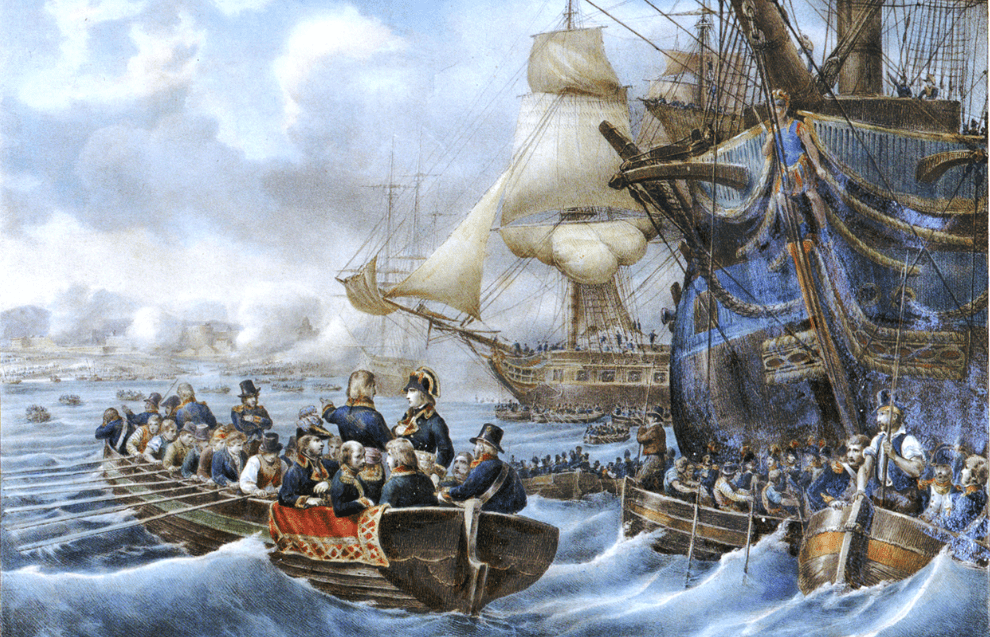

As for the navy, it had the frigates Royal George (26) and Inflexible (22), the schooners Maria (14) and Carleton (12), and the Thunderer bombard, and the Loyal Convert gondola (7), various redeaux o floating platforms, the captured gunboats Washington, Lee, and Jersey, as well as more than 100 single-masted ships capable of carrying 35 soldiers; they were carried by the Richelieu River and Lake Champlain. On June 13, 1777, Burgoyne and Carleton reviewed the assembled forces at Fort Saint-John on the Richelieu River, just north of Lake Champlain, and Burgoyne was ceremonially given command. In addition to the five sailing ships built the previous year, a sixth had been built and three had been captured after the Battle of Valcour Island. These provided some transportation as well as military cover for the large fleet of transport ships that moved the army south on the lake. Burgoyne's army consisted of 3,016 regulars in the 7th Regiment (9th, 20th, 21st, 24th, 47th, 53rd and 62nd), Grenadiers and Light Infantry of the 29th, 31st and 34th; 3,724 Germans framed in 5 Regiments, 357 artillerymen, 147 recruits, 148 loyalists of the King and rangers of the Queen and 500 Indians, in total 7,899 that with the commands reached 8,200. It had 38 field artillery pieces, 2x24s and 4 mortars. His forces were organized into an advanced force under Brigadier General Simon Fraser, and two Divisions, one British and one Hessian. Major General William Phillips led the British Regular Division which normally deployed to the right, while the Hessian Division under Riedel deployed to the left. Colonel Saint Leger's expedition also assembled in mid-June. His force, comprising British regulars, Loyalists, Hessians, and Rangers from the Indian Department, numbering about 750 men, set out from Lachine, near Montreal, on June 23.

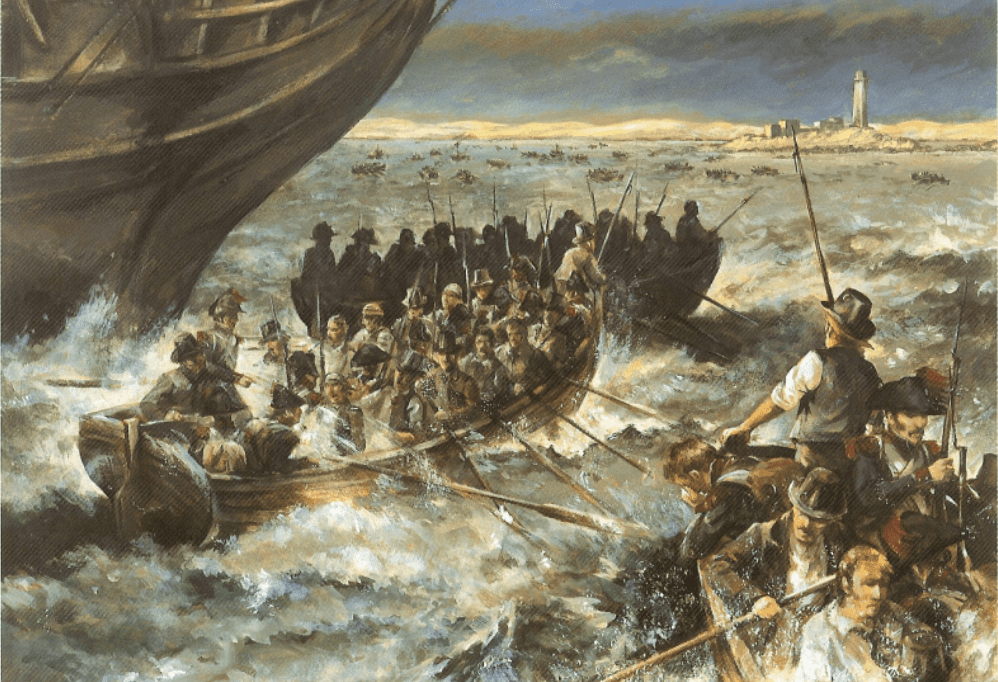

By June 20, everything was ready and the British navy and transports left San Juan for Lake Champlain. Colonel Simon Fraser commanded the forward detachment with his 24th Regiment, 3 Light Companies, 3 Grenadier Companies, 2 Ranger Companies, Canadian Lumberjacks and Indians. He sent ahead parties of Indians, Native Americans, and Canadian Rangers to investigate the American lines and take prisoners. They advanced south to Fort Ticonderoga and ambushed a group of workers. Luckily, one of the captives was an ex-British soldier who had spent the winter working to repair the fort's defences. Under cross-examination, James MacIntosh voluntarily explained every detail of the fort's design, the improvements made by the Americans, and the layout of the land surrounding the fort, including strengths and weaknesses and the ships that had 2 galleys (2×12), 1 gondola (2×9), and more than 30 usable boats. Burgoyne's army traveled across the lake and occupied the defenseless Crown Point Fort by 30 June. The cover activities of Burgoyne's allied Indians were very effective in preventing the details of their movements from being learned by the Americans. Brigadier General Arthur Saint-Clair, who had been left in command of Fort Ticonderoga and its surrounding defenses with a garrison of some 3,000 Continentals and militia, had no idea on July 1 of the total strength of Burgoyne's army, of which large elements were then only 6.5 away. Schuyler had ordered Saint-Clair to hold out as long as possible, and he had planned two routes of retreat. Ticonderaga Fort had been known as the English Gibraltar of America, it had facilities to house 10,000 people, but it was in a state of abandonment when the North Americans conquered the fort in 1775 to seize its cannons.

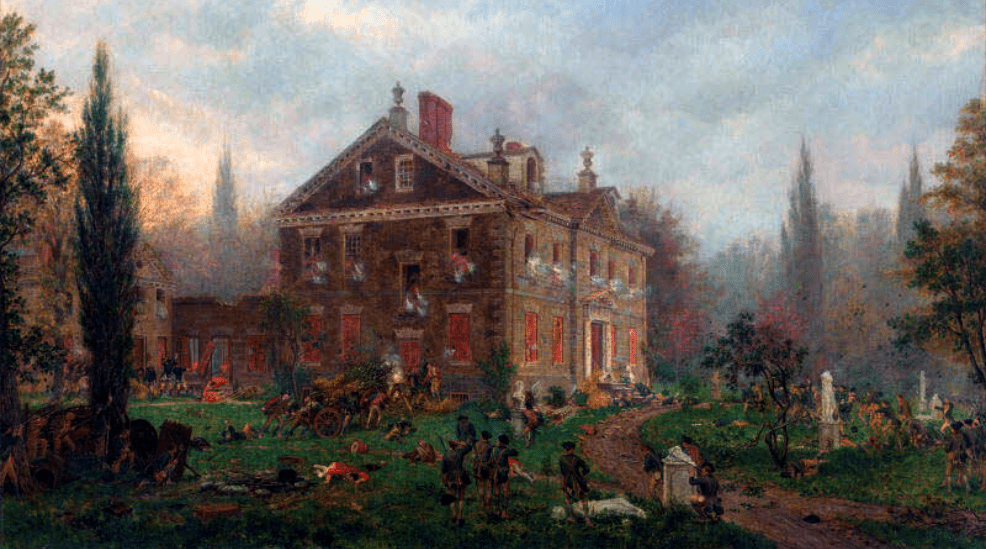

During the winter of 1776-77, MG Arthur Saint-Clair, the congressionally appointed officer to command Fort Ticonderoga and surrounding forts, strove to bring the fort into a state of adequate defense. Saint-Clair and his men faced considerable difficulties. Ticonderoga, originally Fort Carillon, had been built by the French to keep the British at bay and was therefore facing south, the wrong direction to resist the British incursion. With the end of the French and Indian War, Ticonderoga had lost its purpose and been left to fall into disrepair. In the summer of 1776, an American officer, Lt. Col. John Trumbull, prepared a report on Ticonderoga's defenses. Trumbull recommended that the axis of defense be moved from the existing fort to a mountain on the opposite side of the lake, then known locally as Mount Rattlesnake. The recommendation was accepted, and in keeping with the spirit of the times, Mount Rattlesnake became Mount Independence. Unfortunately, Trumbull's additional recommendation, that a rise called Sugar Hill or Mount Defiance that dominated the entire area should also be fortified, was ignored. It seemed enough to change the name to Mount Independence. Saint-Clair's engineering officer, Colonel Jeduthan Baldwin, worked tirelessly in the face of shortages and disease to prepare Ticonderoga for attack by the British. By July 1777, Baldwin had built batteries, storehouses, and blockhouses, and to link the old Fort Ticonderoga with the fortifications on Mount Independence, a bridge and boom barrier (made of chain-linked logs to keep out traffic) were built. the British fleet. On Mount Independence, the Polish military engineer, Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, built batteries and fortifications. Kosciuszko again advised the fortification of Sugar Hill, but the work was not carried out because there were too few American troops to carry carry out the additional work.

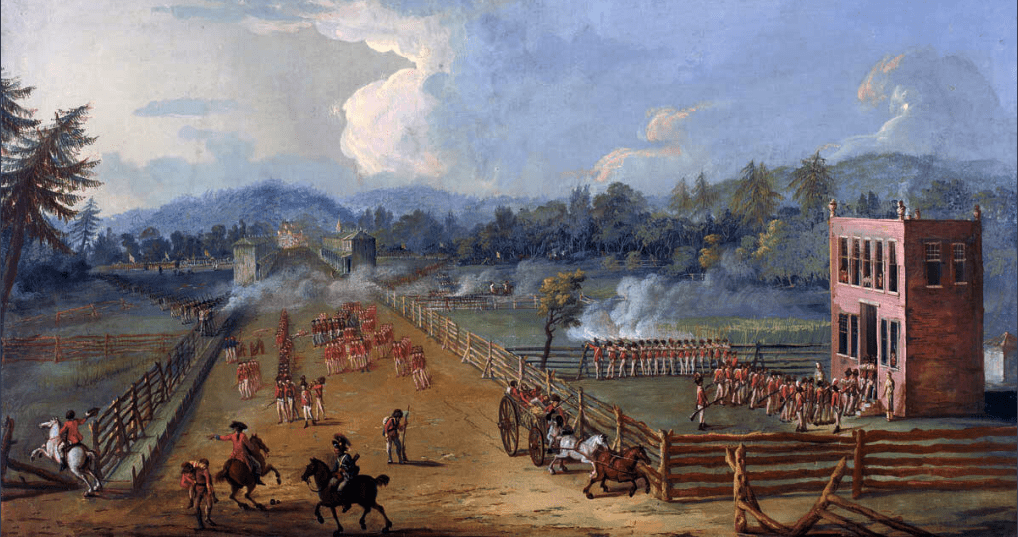

The spirit of the American garrison was good. There were very few of them, but they were ready to fight. Parties of the New England militia arrived at the camp, stayed long enough to exhaust the garrison stores, and returned home. The garrison numbered at least 2,300, from Hale's, Cilley's, and Scammell's New Hampshire mainland RIs from Francis and Marshall's Massachusetts militia, and various other units; these forces were largely inadequate for the defense of a fort of that size. Consequently, plans were made for withdrawal along two routes. The first was by water to Skenesboro, the southernmost navigable point on the lake. The second was overland on a road in poor condition leading east toward Hubbardton in the New Hampshire (present-day Vermont) concessions. On July 1, Saint-Clair was still unaware of the full strength of Burgoyne's army, which was only 6.5 km away, the vanguard composed of Indians and light infantry already watching the fort to report. Burgoyne landed his forces, Phillips's British Division on the right was composed of the 1st Brigade under Brigadier General Henry Watson Powell with the 9th, 47th and 53rd Regiments; and the 3rd Brigade commanded by Brigadier General James Inglis Hamilton composed of the 20th, 21st, and 62nd Regiments. Riedesel's Hessian Division Johann Specht's 1st Brigade with Rhetz, Riedesel, and Specht RIs; von Gall's 2nd Brigade, with the Prinz Friedrich and Hesse-Hanau Regiments; plus an advanced detachment under Tcol Heinrich Breymann, made up of jägers under Major von Barner, dismounted dragoons under Lt. Colonel Baum, and grenadiers also under Breymann. On July 2, open skirmishing began at the outer defense works of Fort Ticonderoga.

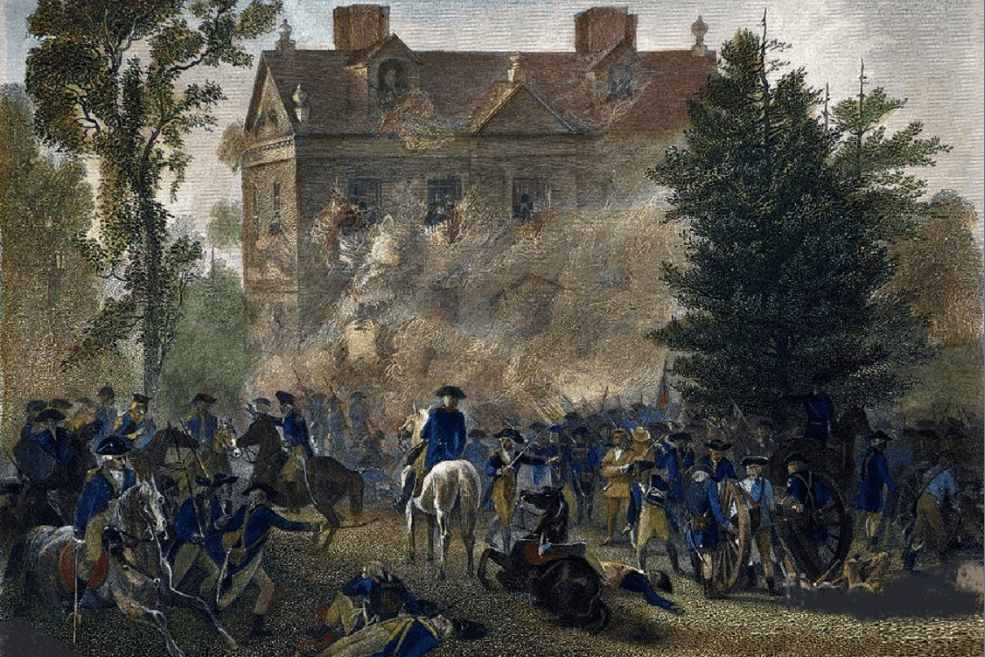

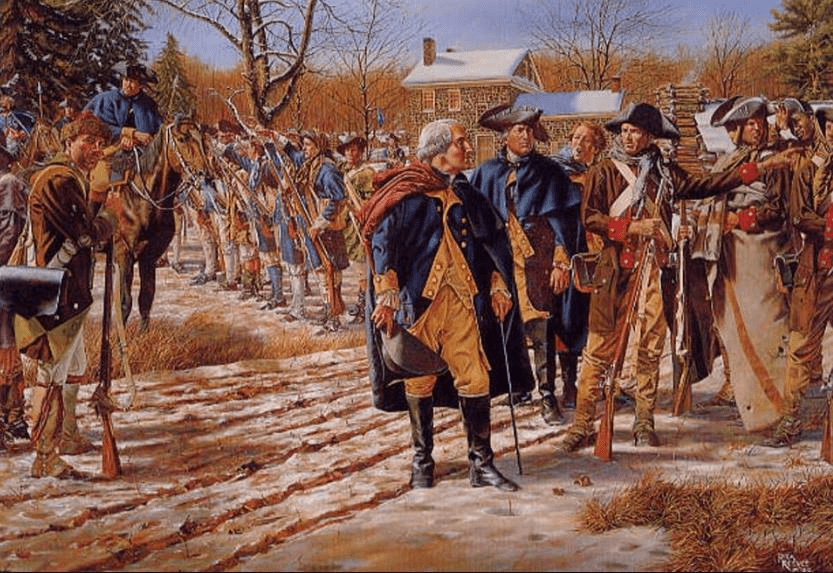

Burgoyne quickly recognized the importance of Mount Defiance and placed artillery there. Arthur St. Clair, commander of the garrison at Ticonderoga, had prepared two escape routes, knowing that his outnumbered force had little chance of defending the fort against a concentrated British attack, but he was ordered to hold the fort as long as possible. possible time. However, when he learned of the guns at Mount Defiance and a British attempt to cut off his escape, St. Clair decided, risking his reputation, to abandon the fort. In the early hours of July 6, 1777, the American garrison evacuated Ticonderoga with the British advance guard hot on their heels. The political and public outcry after the withdrawal was significant. Congress was horrified and criticized Schuyler and Saint-Clair for the loss, even rumors circulating that Saint-Clair and Schuyler were traitors who had accepted bribes in return for withdrawal. Schuyler was eventually removed as commander of the Northern Department, and replaced by General Gates. Saint-Clair was removed from his command and sent to headquarters for investigation. He maintained that his conduct had been honorable and demanded a court-martial review. The court-martial did not take place until September 1778 due to political intrigues against Washington, but he was eventually completely exonerated, although he was never given another command. Schuyler was also acquitted by a court-martial. The news made headlines in Europe. King George reportedly burst into the queen's chambers scantily clad, exclaiming, "I have beaten them! I have beaten all Americans!" The French and Spanish courts were less pleased with the news, as they had been supporting the Americans, allowing them to use their ports and trading with them. The action encouraged the British to demand that Spain and France close their ports to the Americans. This demand was rejected, which increased tensions between the European powers and would have negative consequences for England.

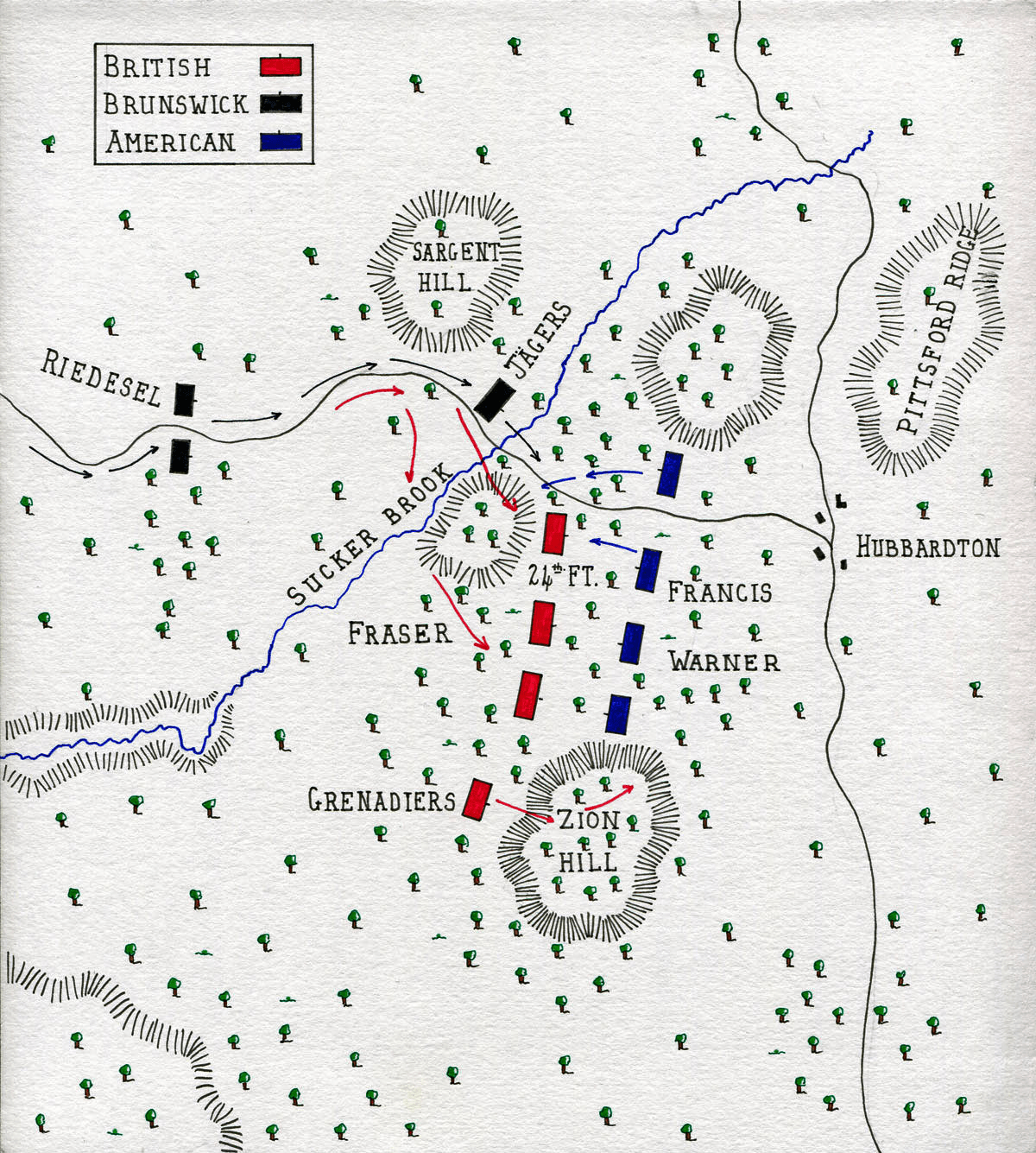

The British general, a Scotsman named Simon Fraser, discovered early on July 6 that the Americans had abandoned Ticonderoga. Leaving a message for General Burgoyne, he summoned the Grenadier Companies and Light Infantry Companies, as well as 2 Companies of the 24th and about 100 Indian Rangers and Scouts, and began pursuit, leaving a message for General Burgoyne to send reinforcements. as fast as possible. Burgoyne ordered Riedesel to follow him. Tcol Breymann initiated the pursuit with a company of jägers and 80 grenadiers, with the rest of the detachment following, he set off with a few companies of Brunswick jägers and grenadiers, leaving orders for the rest of his troops to come as quickly as possible. Fraser was hot on the heels of the retreating Americans, having some clashes with the two alternating rear Regiments. Sait-Clair paused at Hubbardton about 25 miles from Ticonderoga to give the tired and hungry troops of the main army time to rest while he waited for the rear guard to join. When he failed to arrive on time, he left behind Colonel Seth Warner with the Green Mountain Boys, along with the 2nd New Hampshire under Colonel Nathan Hale, at Hubbardton to await the rear while the main army marched on Castleton. When Francis Ebenezer arrived with the 11th Massachusetts, he along with Hale and Warner decided, against Saint-Clair's orders, that they would spend the night there, rather than march on Castleton. Warner, who had experience in rearguard actions while serving in the invasion of Quebec, organized the camps in a defensive position on Monument Hill and established patrols to guard the road to Ticonderoga. Baron Riedesel caught up with Fraser around 4:00 p.m., insisting that his men go no farther before making camp.

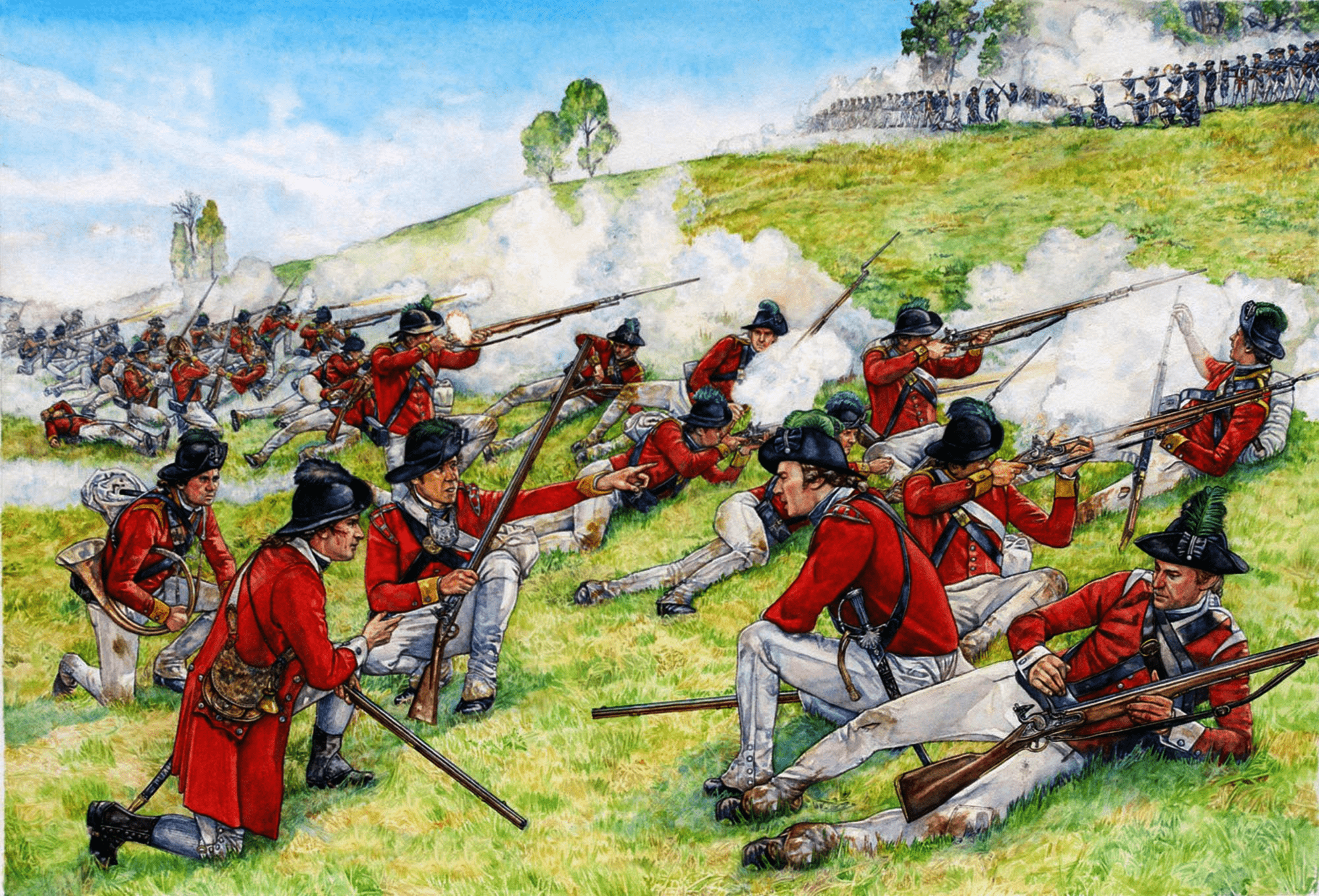

Fraser agreed, as Riedesel was superior, but noted that he was authorized to attack the enemy and would leave his camp at 03:00 the following day. He then advanced until he found a place about 5 km from Hubbardton, where his troops camped for the night. Riedesel waited for most of his men, some 1,500 soldiers, and Fraser also camped with the British 24th, with the grenadiers and light infantry, resumed the advance at 3 a.m. the next day and, meeting the Americans over breakfast , quickly attacked. The first Americans to be mugged, Hale's 2nd New Hampshire, gave way in disarray. The Warner and Francis Regiments formed quickly and resisted strongly. The fighting was intense and Major Grant, in command of the 24th, was killed. The Americans formed a line that stretched across the forested country, with hills on each flank. Brigadier General Simon Fraser sent his grenadiers up the hill on the American left and outflanked them. The hill was steep and the encircling movement of the grenadiers took longer than expected. Meanwhile, Colonel Francis advanced around Fraser's left flank, reinforced by some of Hale's Regiment returning to the battlefield. Fraser, whose force was outnumbered by the Americans, found himself in some difficulty. The sound of battle was heard by General Sait-Clair, the American commander, who was to the south. He ordered Henry Brockholst Livingston and Isaac Dunn to send the militia camped closer to Hubbardtonque to support the stragglers, but the militia refused. To the northwest, the German officer, Baron Riedesel, also heard the shots and rushed to support General Fraser. Riedesel sent Brunswick's jägers ahead, and when they reached the battlefield they attacked the American right flank.

Riedesel's grenadiers were a disciplined force who entered the fray singing hymns to the accompaniment of a military band to make them appear more numerous than they really were. The American flanks gave way and they were forced to make a desperate run across an open field to avoid being enveloped. Colonel Francis fell to a round of musket fire as the troops turned away from the advancing British and scattered across the field. The gunfire was heavy and the balance of the battle shifted in favor of the British, as the Grenadiers finally cleared the hill on the American left and Fraser attacked their center. Colonel Francis was killed and the American line began to break down. The scattered remnants of the American rear guard laboriously made their way toward Rutland to join the main army. Beset by scouts and Fraser Indians, and without food or shelter, it took some of them five days to reach the army, which was closing in on Fort Edward. Others, including Colonel Hale and a 230-man detachment, were captured by the British while clearing the area. Colonel Francis, as a mark of respect on the part of his opponents, was buried with the Brunswick dead. Baron Riedesel and the Brunswickers left for Skenesboro the next day, much to General Fraser's annoyance. His departure left him in "the most disaffected part of America, every person a spy", with 600 tired men, a sizeable contingent of prisoners and wounded, and no significant supplies. On July 9 he sent the 300 prisoners, under light guard but with threats of reprisal if they attempted to escape, to Ticonderoga while he marched his depleted forces to Castleton and then Skenesboro. Livingston and Dunn, the two men sent into battle by Sait-Clair, met the retreating Americans on the Castleton road after the battle was over.

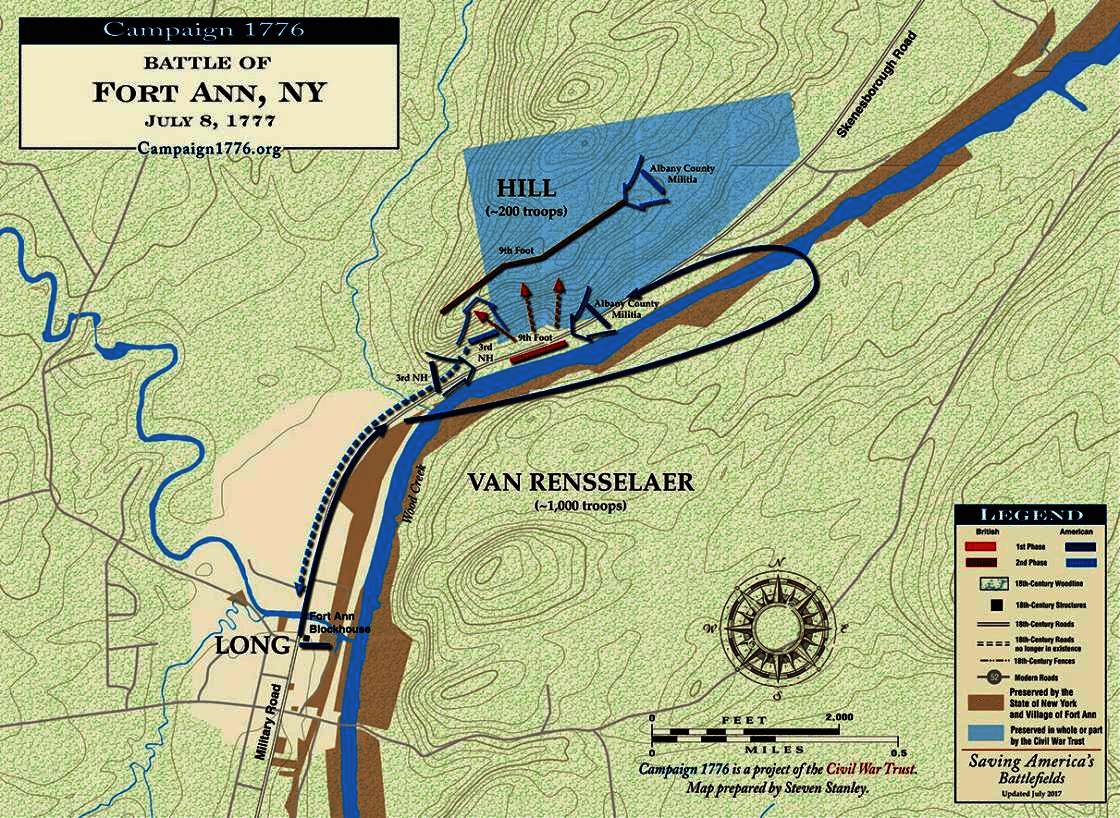

They returned to Castleton with the bad news, and the army departed, finally reaching the American camp at Fort Edward on July 12. The British lost for a total of 50 killed and 143 wounded, while the Americans lost 41 killed, 96 wounded and 230 captured, losing 12 guns. The American forces withdrawing from Ticonderoga were divided: one force followed a route from the lake to Skenesborough; the other followed an overland route to Hubbardton. British naval gunners shelled and destroyed the American ships Enterprise, Gates, and Liberty at the Battle of Skenesborough, two ships, Trumbull and Revenge, were forced to surrender on Lake Champlain, American supplies were destroyed or abandoned to the British. After the battle, the Americans fled as best they could in the direction of Fort Anne in total confusion; heading south through a maze of difficult trails and dense forest, closely pursued by Lt. Col. John Hill's British RI-9, with orders to pursue and defeat any retreating forces and take control of Fort Anne. British pursuers under Hill captured more American supplies, as well as sick, wounded, and camp followers left behind. When they were within a mile of Fort Anne, Captain James Gray with a force of 220 men, took in the fugitives, and engaged the British. In the ensuing skirmish, one American was killed and three others wounded before the Americans withdrew to the fort. On the morning of July 8, Hill was informed by a suspected American deserter, who was really a spy, that the fort was occupied by nearly 1,000 demoralized troops. Choosing not to attack a numerically superior force, Hill sent a message to Burgoyne explaining the situation.

Burgoyne ordered the 20th and 21st to march quickly to Fort Anne in support, but bad weather hampered their movement and they would not arrive until after the battle. The 'deserter' returned to Fort Anne and reported on the British position and his strength of 200. The prospect of Colonel Pierse Long, commander of the fort who had 200 militiamen to successfully defend the fort, seemed dire until Colonel Henry K. Van Rensselaer unexpectedly arrived at the fort with 400 militiamen, raising the number of troops to about 1,000 and reinvigorating the moral. Long, seeing the few British soldiers following him, decided to attack his position. Moving as stealthily as possible, his force attempted to encircle the British while they were still in the way. However, Hill's men heard rebel movements on their flanks and withdrew to a higher position, abandoning some wounded men, who were eventually captured by the Americans. When the Americans opened fire, it was "heavy, well-aimed fire," according to a British officer. The battle lasted more than 2 hours, until both sides ran out of ammunition and the British were practically surrounded by Americans. The sound of North Indian war cries prompted the Americans to retreat, and they retreated to the fort with their wounded, including Colonel Van Rensselaer, who had been shot in the hip. As it turned out, there were no Indians, but only a British officer, John Money of the 9th, who had led a group of Indians, but when they seemed reluctant to fight the Americans, Money grew impatient and ran ahead of them. It was his war cries that ended the battle. Back at the fort, the Americans held a brief council of war. From a woman the British had freed, he reported that 2,000 or more British troops under General Phillips were advancing rapidly.

Long's men, nearly out of ammunition, retreated towards Fort Edward, burning the fort to the ground. Both sides claimed victory in the battle, as the British had successfully held out and the Americans had nearly forced them to surrender. British casualties were 13 killed, 22 wounded and 3 missing; US casualties were about 50 dead and wounded. Brigadier Barry Saint-Leger left Montreal on June 23, he had 300 regulars reinforced by 650 Canadians and loyalist militiamen. Two days later he arrived at Fort Oswego, where he was joined by John Johnson and Joseph Brant with almost 1,000 Iroquois, the next day, they crossed Oneida Lake and, the warriors selected by Brant, headed up Wood Creek, doing 16 km per day. , despite the terrain and frequent enemy obstacles. His first objective was Fort Stanwix, situated between Wood Creek and the Mohawk River, which Saint-Leger believed to be a ruin guarded by 60 men. In fact, it had been garrisoned since April by 550 men of the 3rd New York under Colonel Peter Gansevoort, who had largely rebuilt it (despite the fact that a French engineer, Captain de Marquisie, had wasted several weeks trying to design a brand new fort). On August 2, an advance detachment from Saint-Leger, had been detached to intercept a supply convoy headed for the fort, arrived too late to stop the 200 men escorting ships full of six weeks' worth of ammunition and provisions to the fort. The next day, Saint-Leger arrived with his main body and, seeing that his artillery was too weak in number and caliber, decided to invest the fort and send a parliamentarian requesting his surrender. Seeing the scarcity of white troops and the preponderance of Indians, Gansevoort rejected the proposal. Later that day, a flag made from a soldier's shirt and a woman's petticoat was raised at the fort.

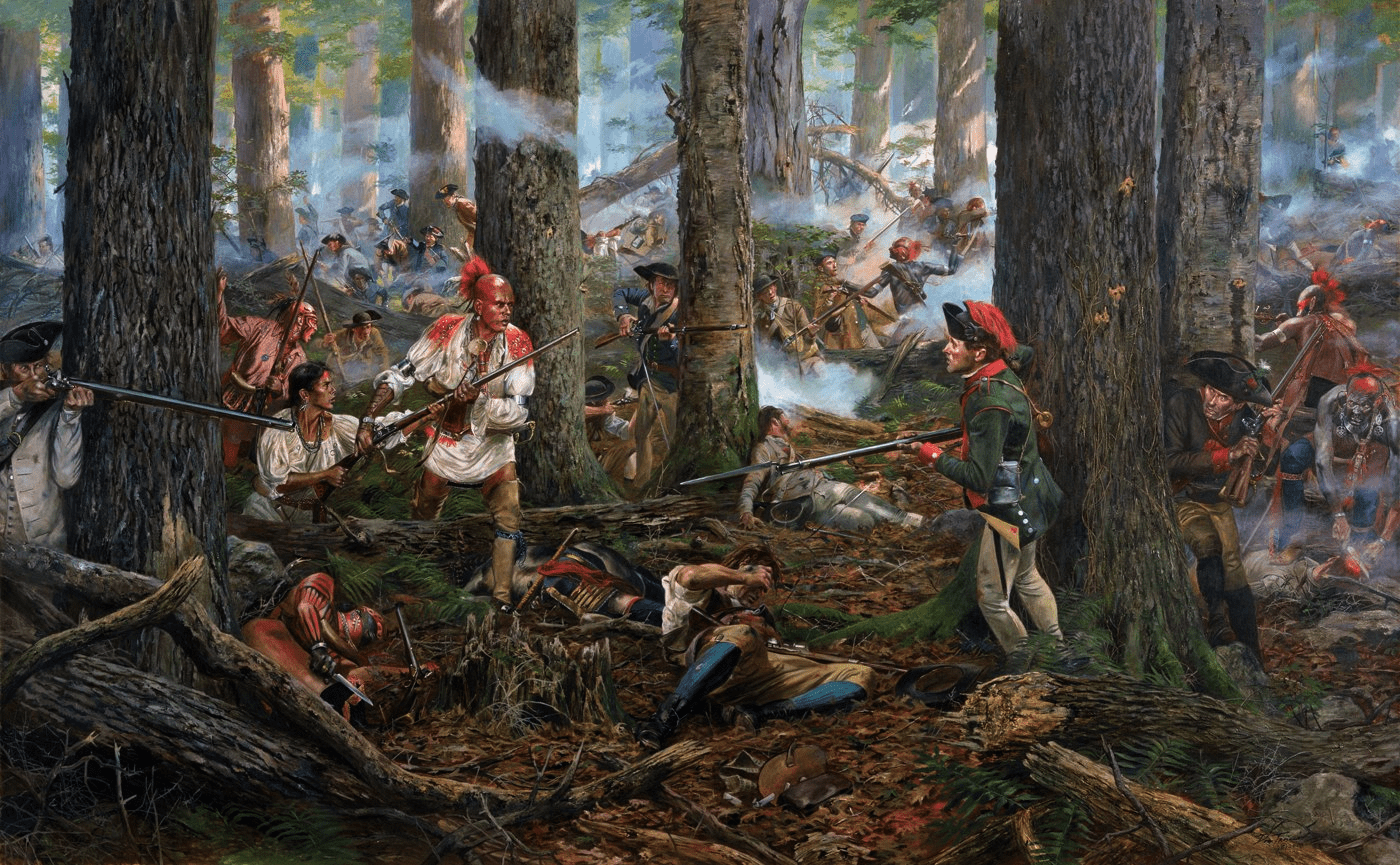

As the majority of Saint-Leger's force began building trenches, clearing Wood Creek and cutting off the supply road through the woods, Indian jägers and marksmen began to fire on the garrison, with some success. However, on the night of August 5, Saint-Leger heard that a relief force had left Fort Dayton the day before and was some distance from his camp. Unwilling to risk a battle where the garrison might intervene, he sent Johnson and Brant, with 150 Loyalists and 400 Mohawks, to ambush the approaching column. Four Regiments of the Tryon County militia, each 200 strong, had been meeting since July 30, when its commander, Brigadier General Nicholas Herkimer, had called all men between the ages of 16 and 60. They set out from Fort Dayton on August 4, covering 12 miles before camping at Stirling Creek. The next day they crossed the Mohawk River and by nightfall were within 8 miles of Fort Stanwix. However, Herkimer was concerned, his route was dangerous, and defeat would leave Gansevoort isolated and the valley defenseless. He then sent four men to warn Gansevoort of his approach and ask him to make a sortie. The arrival of the four men was to be acknowledged by three cannon shots. In the middle of the morning of August 6, he still didn't know anything. His colonels demanded action, accusing him of cowardice and reminding him that he had at least a force like Saint-Leger. Stung by his insubordination, and marginally reassured by the arrival of 60 Oneidas and 50 Rangers, he gave the marching order. By 0900 hours, they had already reached a point where the road was crossed by two steep ravines, the first 300 meters wide and 16 meters deep, the second smaller, but enough to hide men from view. Both ravines were heavily shaded by trees, which grew a few meters from the road.

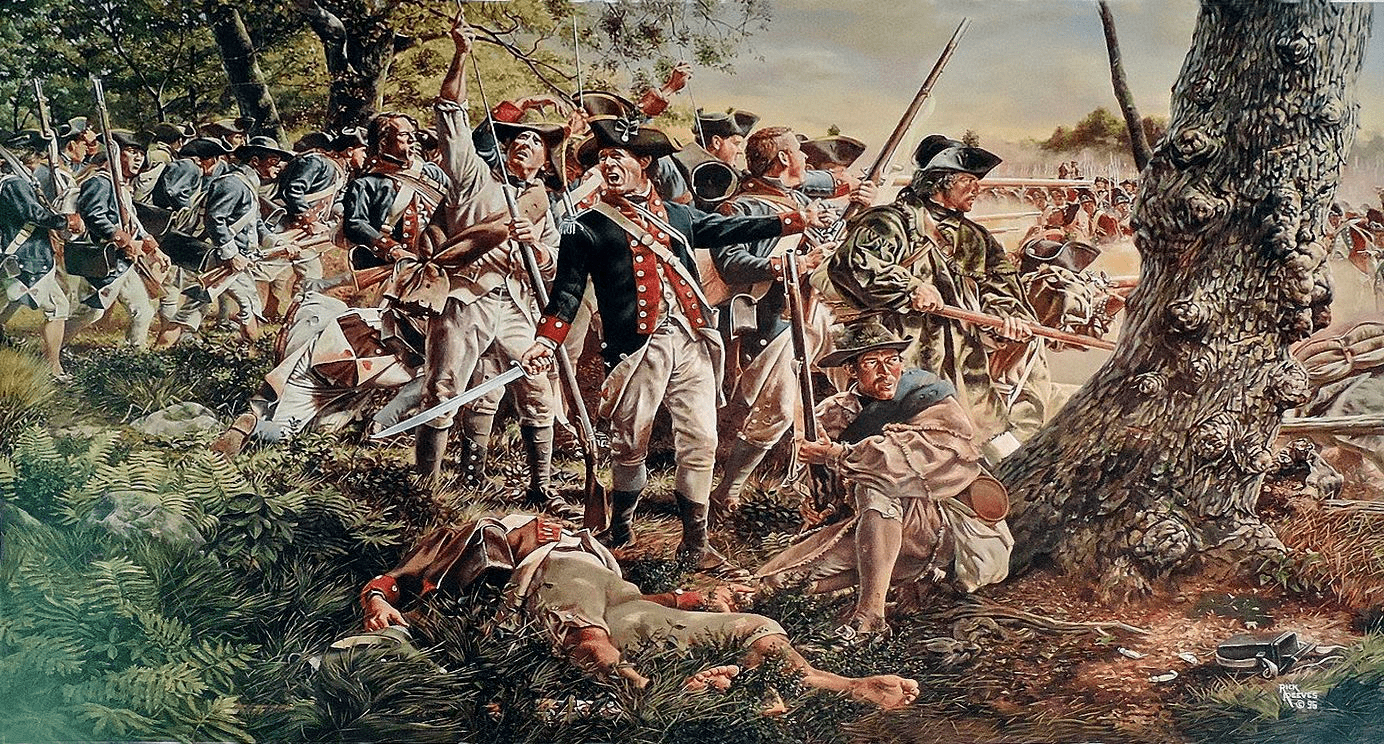

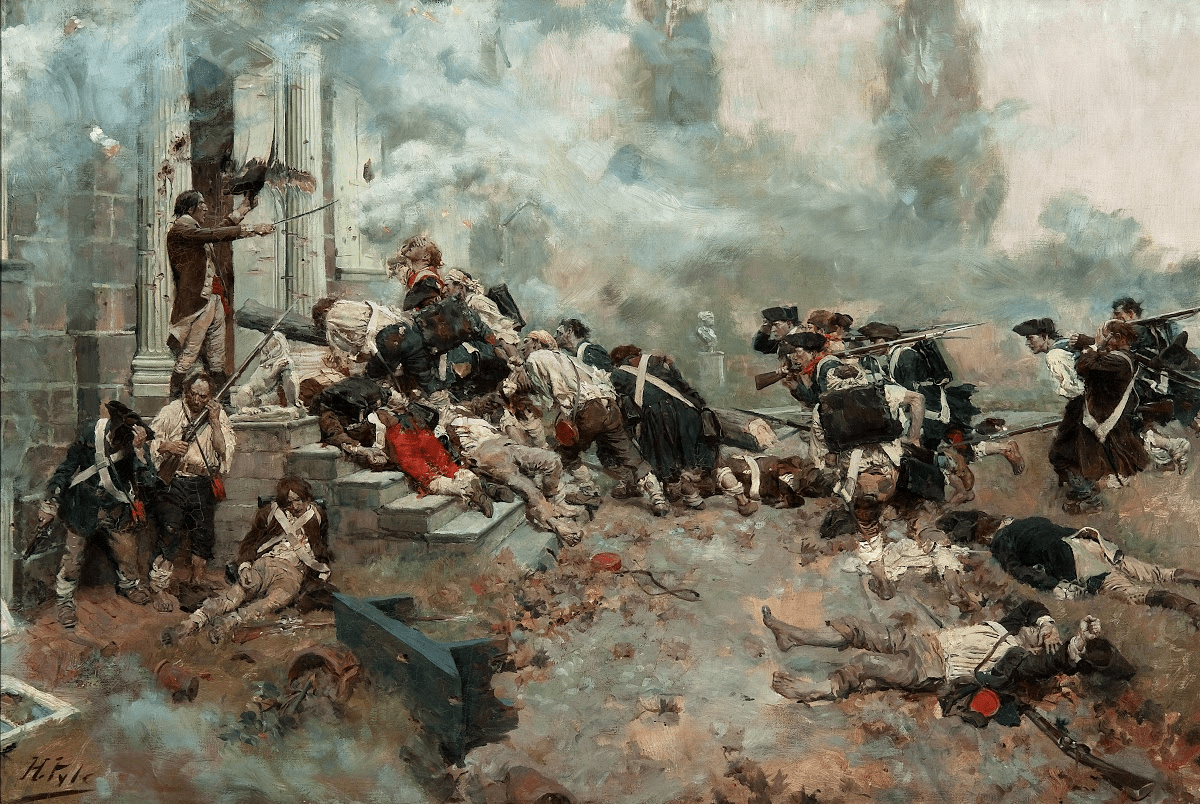

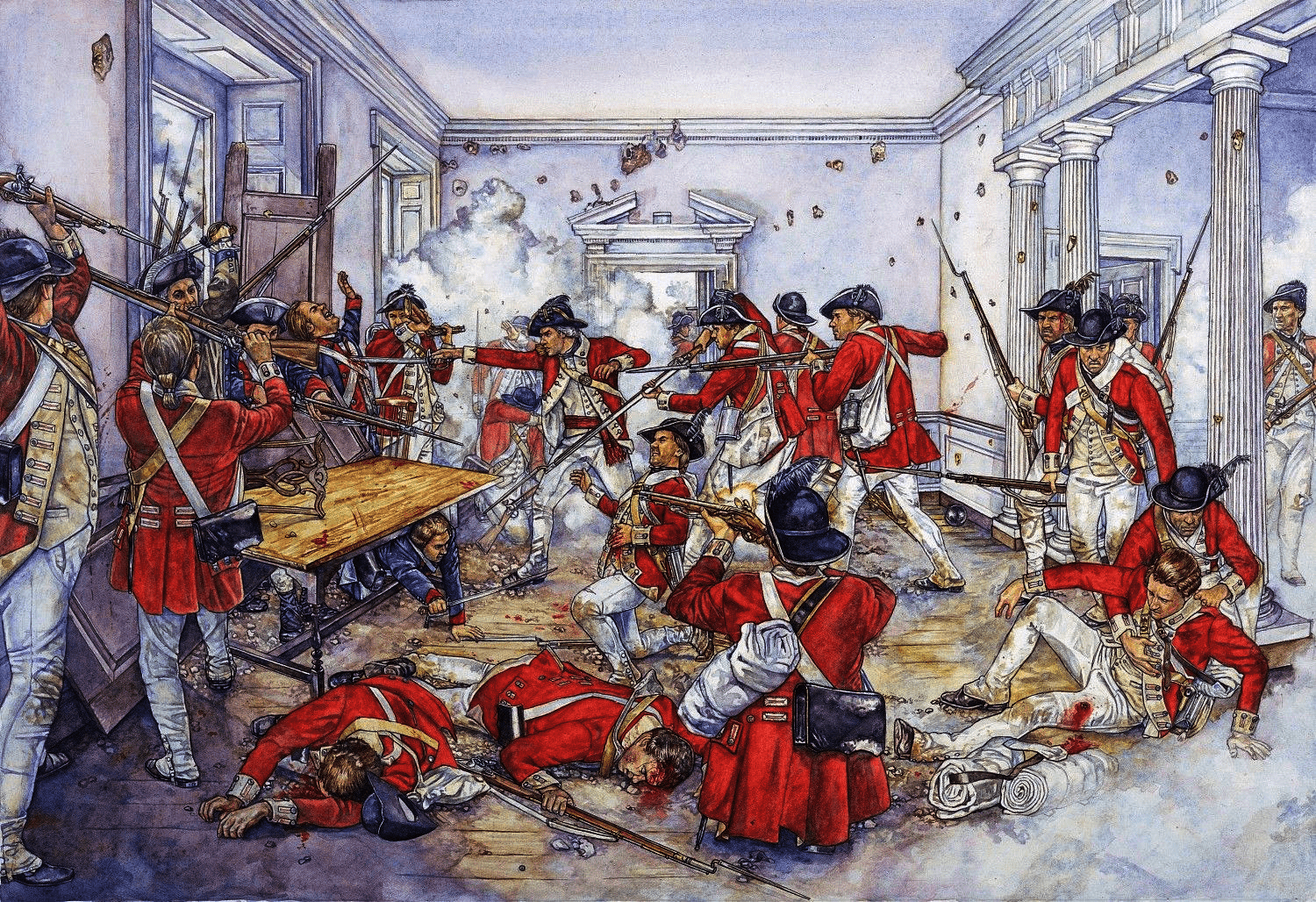

The convoy marched with 3 Regiments in front behind the wagons with provisions and in the rear another RI, Herkimer began to leave the second ravine, three whistles were heard. Johnson had laid an ambush, bringing the loyalists forward to block the road, and the rangers and Indians to attack both flanks of the force trapped in the ravine and then have the natives rush in to decimate the column trapped in the ravine. ravine. Unfortunately, the Mohawks attacked too early, failing to close the rear and leaving an escape route. As a result, the portion of Herkimer's men outside the ambush zone quickly fled, pursued by Mohawks for several miles. Herkimer himself was hit in the leg. His men laid him down against a tree, but when they suggested that he retreat to the rear, he replied, "I will fight the enemy" and sat quietly leading the battle. When the smoke cleared after the initial attack, Herkimer had lost roughly half his men killed, wounded, or fled. An electrical storm halted the fighting for nearly an hour, allowing Herkimer to rally his shattered forces. Herkimer ordered his men to fight in relays, with one charging while the other fired, greatly lessening the American's vulnerability to armed natives for close quarters. Loyalists tried to break into the American lines by posing as a reinforcement of the fort, turning their green coats inside out to try to pass themselves off as patriots. Captain Gardenier saw through the ruse and turned on them. By 11:00, Herkimer's messengers had reached the fort, and the requested sortie was finally arranged. When the storm passed, US Lt. Col. Marinus Willett came out with 250 men and proceeded to storm the unoccupied British camp, seizing 21 wagons of material and supplies without a single casualty.

A nearby scout informed Johnson's forces. When their native allies realized that their camps were being raided, they immediately abandoned the battle to protect their families and possessions. With the loss of his native allies, Johnson was also forced to withdraw. Herkimer and his men retreated to Fort Dayton, where his shattered leg was amputated. He died of his injuries on August 16. American losses were 385 killed and another 80 wounded and captured. The British lost 7 killed and 21 wounded, while their native allies suffered 65 casualties. General Philip Schuyler learned of Oriskany's withdrawal and immediately organized an additional relief force to be sent to the area. Arnold's relief column reached Fort Stanwix on August 21, sending messengers into the British camp who convinced the besieging British and Indians that their force was much larger than it really was. They abandoned their siege and withdrew. Ultimately, the British forces in the Mohawk Valley had achieved very little. Burgoyne's progress toward Albany had initially met with some success, including the dispersal of Seth Warner's men at the Battle of Hubbardton, where the American rear guard was defeated. However, his advance had slowed by the end of July, due to logistical difficulties, exacerbated by the American destruction of key roads, and army supplies began to dwindle. Burgoyne's concern for supplies increased in early August when he received word that Howe was going to Philadelphia and that, in fact, he would not be advancing up the Hudson River Valley. In response to a proposal first made on July 22 by the commander of his German troops; Baron Riedesel, decided to send a detachment of some 800 soldiers under the command of Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum from Fort Miller on a mission to forage and purchase horses for the German dragoons, requisition animals to help move the army, and harass the enemy.

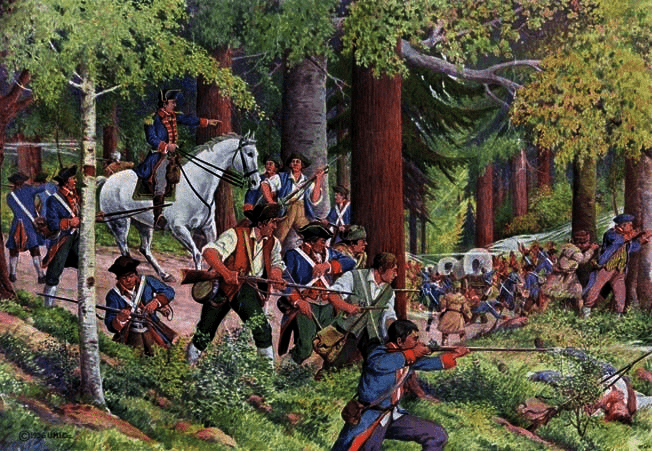

Burgoyne's circumstances were far from promising. His army fought through the heavy forest from Ticonderoga, building a road to transport artillery and chariots. The Americans systematically devastated the country, leaving Burgoyne's army without supplies or reliable transport. Burgoyne's troops had so few horses that the Brunswick dragoons followed on foot. The difficulties proved yet another reminder of the problems of campaigning in the vast forests of North America, experienced by every British general since General Braddock in 1755. The final blow was a letter from General Howe in New York, informing Burgoyne of that the main British army would set out to invade Pennsylvania; instead of advancing down the Hudson River to meet him at Albany, as envisioned in the original plan for Burgoyne's campaign devised by Lord Germaine, Prime Minister in London. Burgoyne ordered Colonel Baum to take a force to Manchester in Vermont, east of Fort Edward, to find horses for his dragoons and for army transport, to gather food supplies and to overwhelm rebellious settlers in the area. At the last moment, Baum's target was changed to the town of Bennington, based on reports of supplies available there. The withdrawal of the US Continental Army from Fort Ticonderoga and the advancing British Army were causing considerable alarm in Vermont and New Hampshire. Distrusting the aristocratic New Yorker, General Schuyler, who with General Saint-Clair was suspected of treason upon leaving Fort Ticonderoga, the New Hampshire Council formed a Militia Brigade commanded by Colonel John Stark. Stark, a veteran of the French and Indian War and the New Jersey campaign, was highly regarded in the region, and settlers flocked to join his force.

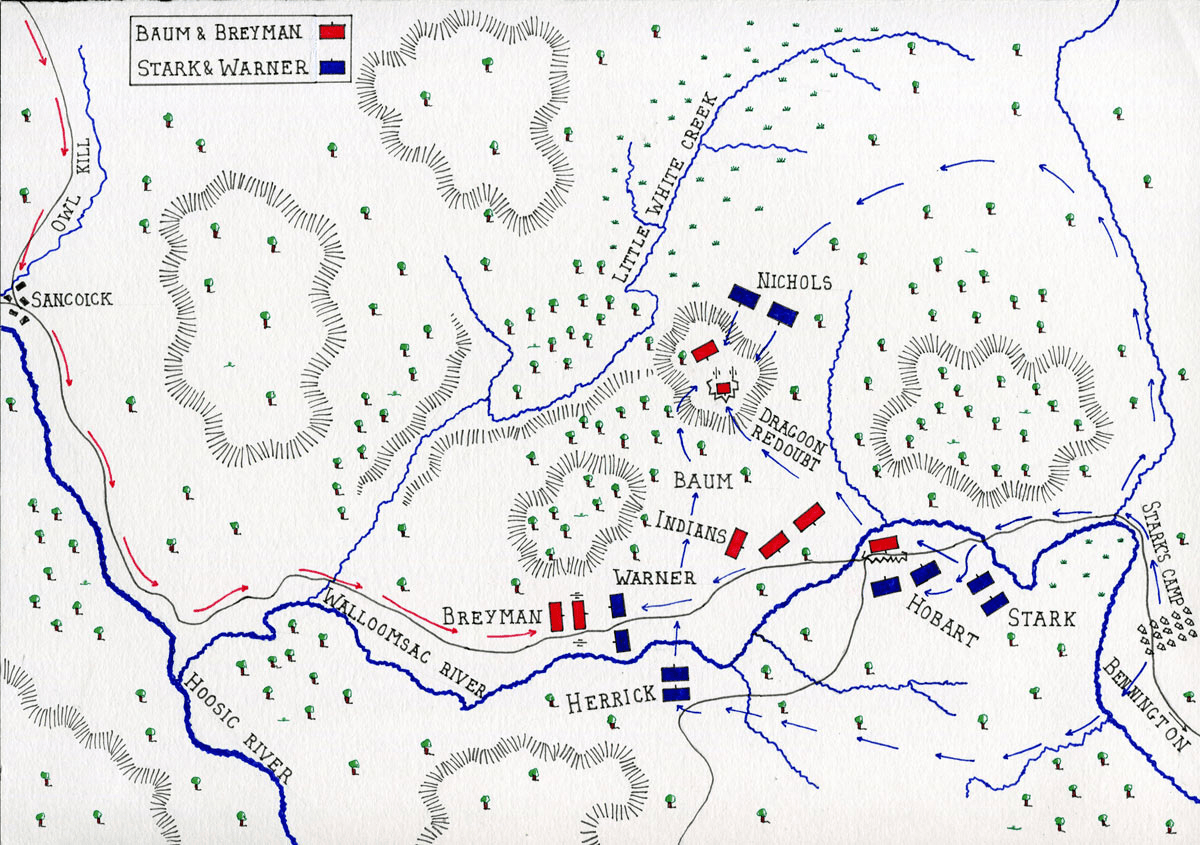

His brigade was at his camp in Bennington. Warner's Green Mountain Boys, licking their wounds after the Battle of Hubbardton, were in Manchester. Baum's detachment consisted mainly of Brunswick dismounted dragoons from the Prinz Ludwig Regiment. Along the way they were joined by local Loyalist companies, some Canadians and about 100 Indians, and a Company of British sharpshooters led by Captain Alexander Ferser of the 34th. Baum was originally ordered to proceed to the Connecticut River valley where they believed horses could be procured for the dragoons. However, as Baum prepared to leave, Burgoyne verbally changed the target to a supply depot at Bennington, which was supposed to be guarded by the remnants of Warner's Brigade, some 400 Colonial militia. On August 11, Baum undertook the 40-mile journey to Bennington, but the dismounted dragoons in their cumbersome uniforms, plus their strict adherence to European military formalities, delayed the march. As they advanced, their Indians ravaged the countryside. On August 13, en route to Bennington, after a skirmish with a small force under Colonel Gregg, Baum learned of the arrival in the area of 1,500 New Hampshire militiamen under Stark's command. Baum ordered his forces to stop at the Walloomsac River, about 5 miles west of Bennington. After sending a request for reinforcements to Fort Miller, Baum took advantage of the terrain and deployed his forces on a hill overlooking the river. In the rain, Baum's men built a small redoubt on top of the hill and hoped that the weather would prevent the Americans from attacking before reinforcements arrived. With a small force of 1,500 men, Stark learned of Baum's presence, and sent messengers to summon militia from the area.

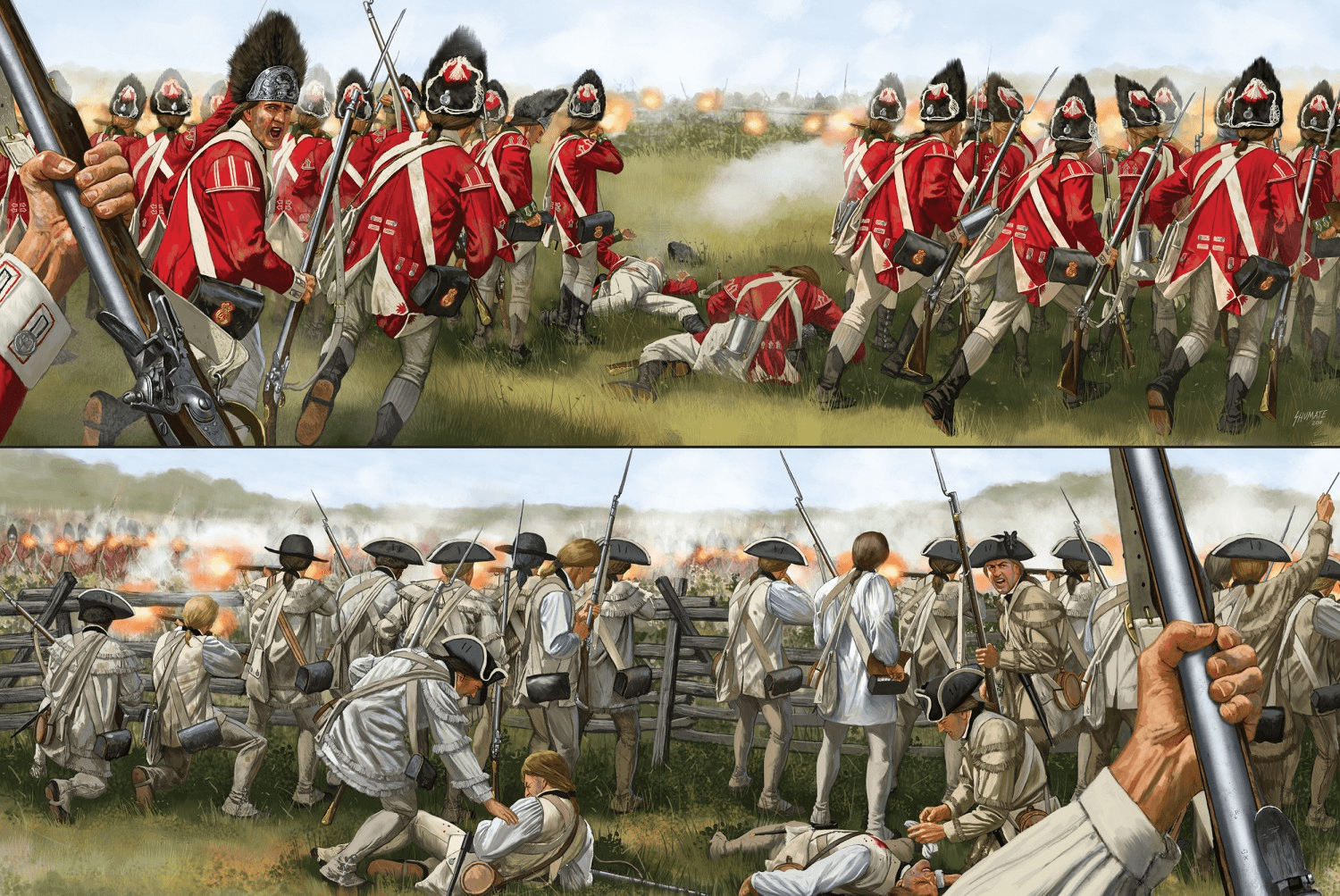

Stark's men and a smaller force of Vermont militia under Colonel Seth Warner were near Bennington, as Baum's expedition prepared to attack. On August 14, the American attackers met and encountered a British scouting party at Sancoicks Mills. After sending out a request for reinforcements, Baum advanced 6.5 km to a hill overlooking the Walloomsac River. Just 5 miles from Bennington, Baum's men dug in and around that hill, expecting more American resistance. It became clear to Baum that he was substantially outnumbered by Stark's force. Baum sent further urgent messages to Burgoyne, requesting support, and Burgoyne ordered Colonel Breyman with his Regiment (550 strong) to march to Baum's aid. Late at night on August 15, Stark was awakened by the arrival of Parson Thomas Allen with the RI of militiamen from Berkshirey County in Massachusetts who insisted on joining his force. Stark's forces were again increased the next day by the arrival of some Stockbridge Indians, bringing his strength to almost 2,100: right flank with 550 from Nichols's Regiment; left flank 500 (300 Herrick's Regiment and 200 Vermont Rangers); center-right 550 militiamen under Starck, and center-left 500 militiamen under Hobart. Stark was not the only beneficiary of unexpected reinforcements. Baum's force increased by nearly 100 when a group of local loyalists arrived at his camp on the morning of August 16; bringing his total force to 800 strong (205 dragoons, 24 grenadiers, 57 light infantry, 37 line infantry, 13 artillerymen, 150 Queen's Rangers, 48 British sharpshooters, 150 Loyalists, 56 Canadians and 100 Indians). On the evening of August 16, the weather cleared and Stark ordered his men to stand ready to attack. He is reputed to have rallied his troops saying they were there to “fight for their natural born English rights and there are your enemies, the Redcoats and the Tories. They are ours, or tonight Molly Stark will sleep a widow."

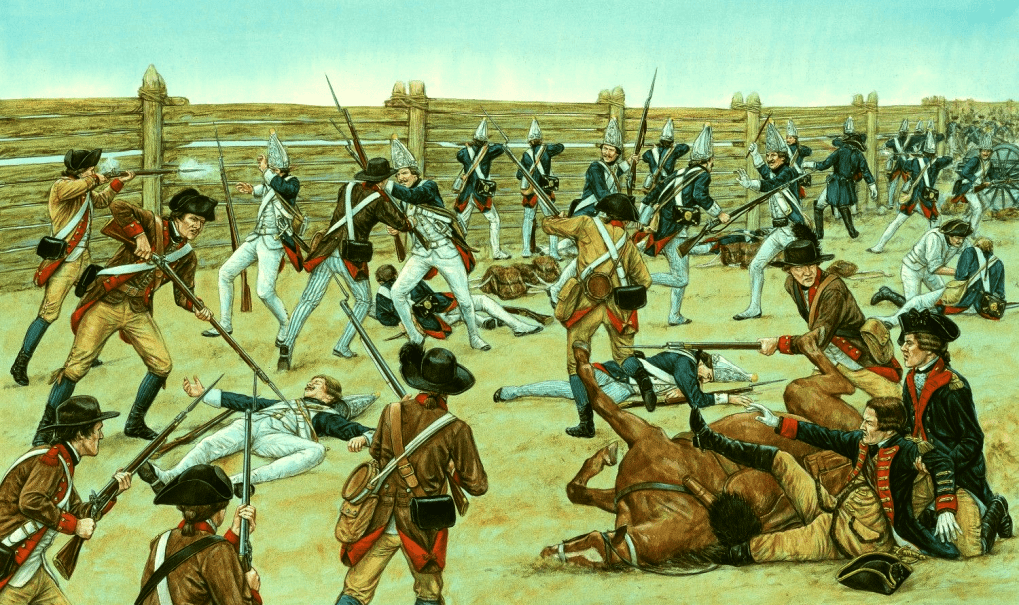

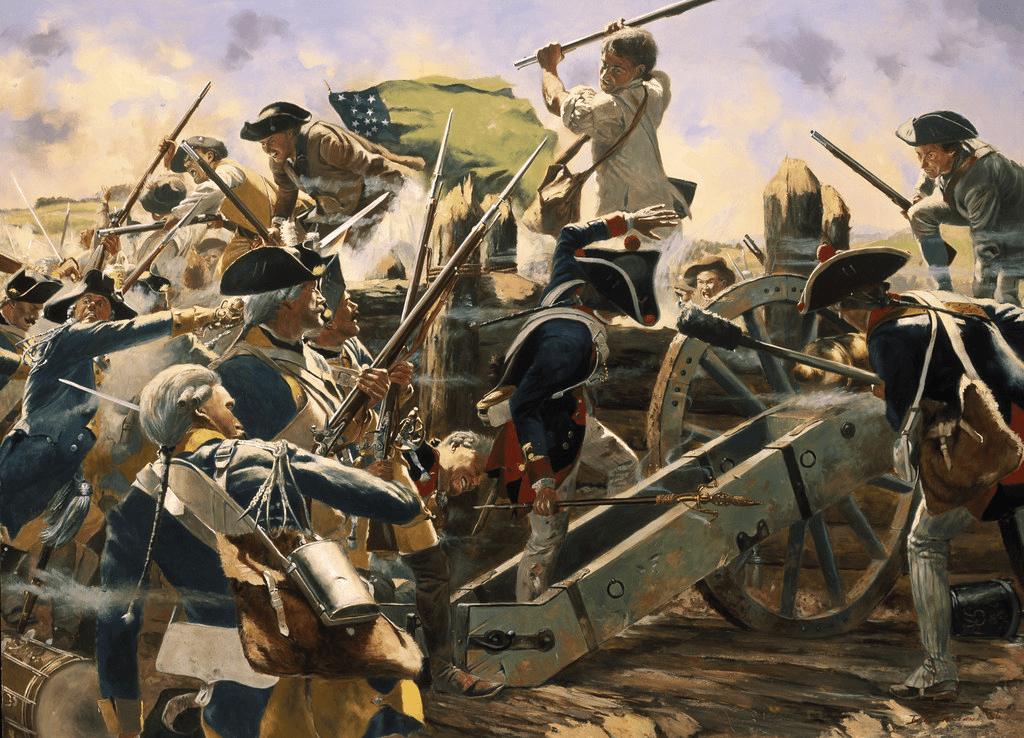

Learning that the militia had disappeared into the woods, Baum assumed that the Americans were withdrawing or redeploying. However, Stark had decided to capitalize on weaknesses in the German's widely distributed position; and he had sent sizeable flanking parties on either side of his lines, under Colonels Nichols on the right (550) and Herrick on the left (500) to attack from the flanks and rear. These moves were supported by a ruse employed by the men of Stark (550) and Hobbart (500), who made a frontal assault to attract the attention of the German and British troops, allowing the flanks to approach safely without alarming. to enemy forces. The Germans, most of whom did not speak English, had been told that soldiers with pieces of white paper in their hats were loyal, and should not be shot. Stark's men had also heard this and many of them had appropriately adorned their hats. Around 3:00 p.m., when fighting broke out, the German position was immediately surrounded by gunfire, which Stark described as "the most fiery engagement I have ever witnessed, resembling continuous thunder." Loyalist and Indian positions were overrun, causing many of them to flee or surrender. This left Baum and his Brunswick dragoons trapped on the high ground alone. The Germans fought valiantly even after running out of powder and the destruction of their ammunition cart. In their desperation, the dragons led a saber-wielding charge in an attempt to break through the encircling forces. The charge failed horribly, inflicting heavy German casualties and failing to gain ground for the rebels.

Baum was mortally wounded in this final charge, and the remaining Germans surrendered. After the battle was over, while the Stark militiamen were busy disarming the prisoners and looting their supplies, Breymann arrived with his reinforcements. Seeing the Americans in disarray, he immediately went on the attack. After hastily regrouping, Stark's forces attempted to hold their own against the new German attack, but began to fall back. Before their lines collapsed, Warner with the Green Mountain Boys arrived on the scene to reinforce Stark's troops. The pitched battle continued until nightfall, when both sides withdrew. Breymann began a hasty retreat; he had lost a quarter of his strength and all of his artillery pieces. The total German and British losses at Bennington that were recorded were 207 killed and 700 captured. American losses included 30 killed and 40 seriously wounded. The battle was at times particularly brutal especially when loyalists met patriots, as in some cases they came from the same communities. The prisoners, who were first held in Bennington, were eventually taken to Boston. Burgoyne's army was preparing to cross the Hudson River at Fort Edward on August 17 when news of the battle first arrived. Believing that reinforcements might be needed, Burgoyne marched the army towards Bennington until news arrived that Breymann and the remnants of his force were returning. Stragglers continued to arrive throughout the day and night, as word of the disaster spread through the camp. The effect on Burgoyne's campaign was significant. Not only had he lost nearly 1,000 men, half of whom were regulars, but he also lost crucial Indian support. In a council following the battle, many of the Indians (who had traveled with him from Quebec) decided to return home.

This loss severely hampered Burgoyne's reconnaissance efforts for days to come. American patriots reacted to news of the battle with optimism. Especially after Burgoyne's Indian screen deserted him, small groups of local patriots began to emerge to harass British positions. A significant portion of Stark's force returned home and did not again become influential in the campaign until they appeared at Saratoga on October 13 to complete the encirclement of Burgoyne's army. On October 4, Stark's reward from the New Hampshire General Assembly for "the memorable battle of Bennington" was "a full suit of clothing which became his rank." One reward Stark probably valued most was a message of thanks from John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, which included a commission as "Brigadier General of the United States Army." The American victory at Bennington also galvanized the Americans and was a catalyst for French participation in the war.