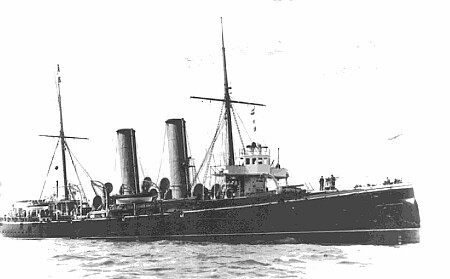

Aug 20, 1100 hours, HMCS Rainbow, Hecate Strait.

The wind had been picking up as the morning progressed, and the turquoise sea was now busy with whitecaps. Rainbow was still working up to her full speed after the rendezvous with Hawk. The smoke from her funnels blew sideways, and due east.

“Set course to take us outside of Cape Scott,” ordered Commander Hose. This route would take Rainbow around Vancouver Island to the west, in the open Pacific. Six Bells was rung on the forenoon watch, and the rum tot was served. As Rainbow headed south, she slowly emerged from the shelter of the Queen Charlotte Islands. The chop of Hecate Strait was joined by, and then replaced by the long swells of the wide Pacific. The cruiser’s bow rose and fell. Green water came over the turtleback foredeck, broke against the V shaped bulwark that served as the lower half of the shield for the forward 6 inch gun, then ran foaming off the sides of the ship.

Sub Lieutenant Brown gave his report to Commander Hose, washed up, then took his station on the aft bridge. From the aft bridge wing he had a clear sight line along the rail, almost to the bow. He noted that the waves rolling along the ship’s side in this sea state almost topped over into the well deck. Consequently the shutters covering the secondary armament embrasures could not be dropped, lest the well deck turn into a swimming pool, and the 4.7 inch and 12 pounder guns could not be swung out. If it came to a fight in these conditions the Rainbow would only be able to use her two fore and aft 6 inch guns.

A messenger brought a wireless transcript to the bridge. RRR SS CORSICAN BEING ORDERED TO STOP BY CRUISER RRR. The message included a position off the west coast of Moresby Island.

Commander Hose looked at the message skeptically. He walked aft to the wireless cabin to consult. “Does the signal strength match the claimed position of the distress call?” he asked the wireless operator.

“It is not inconsistent,” the wireless operator responded. “We would be in a better position with a direction finding set.”

“That we would.” Replied Hose.

The wireless set came to life, and the operator transcribed the message. “Naval Code,” said the operator. He retrieved the current code book and decrypted the message.

DOMINION WIRELESS STATION DEAD TREE TO HMCD ESQUIMALT Y STATION DISTRESS MESSAGES FROM SS CORSICAN SENT BY SAME HAND AS PREVIOUS FALSE MESSAGES STOP MESSAGE IS ALSO MOST LIKELY FALSE STOP

“Surprise, surprise,” said Hose. The messages continued until the phantom Corsican announced her demise.

The day continued, sunny and windy. Periodically, Rainbow received messages of merchant ships being attacked by German cruisers, and the corresponding warning from Dead Tree Station, noting that these were most likely counterfeit. The original signal strengths diminished throughout the afternoon and evening as Rainbow made her way south. But the Dominion Wireless Service relays taunted even as the disk of the sun dipped to the horizon over the open Pacific.

At 2047 hours, Sub Lieutenant Brown on the after bridge, and Commander Hose on the wheelhouse starboard bridge wing, both gasped at the same time as the sun’s last ray dipped below the ocean’s surface and was refracted into that rarest of nautical phenomena, a green flash. To Rainbow’s stern, the Quatsino Sound Lighthouse on Kain's Island blinked. Directly to port, the unbroken wilderness of the Brooks Peninsula was still lit golden on its upper slopes. Some high cloud overhead glowed pink and purple. Tomorrow would be a clear sunny day.

The wind had been picking up as the morning progressed, and the turquoise sea was now busy with whitecaps. Rainbow was still working up to her full speed after the rendezvous with Hawk. The smoke from her funnels blew sideways, and due east.

“Set course to take us outside of Cape Scott,” ordered Commander Hose. This route would take Rainbow around Vancouver Island to the west, in the open Pacific. Six Bells was rung on the forenoon watch, and the rum tot was served. As Rainbow headed south, she slowly emerged from the shelter of the Queen Charlotte Islands. The chop of Hecate Strait was joined by, and then replaced by the long swells of the wide Pacific. The cruiser’s bow rose and fell. Green water came over the turtleback foredeck, broke against the V shaped bulwark that served as the lower half of the shield for the forward 6 inch gun, then ran foaming off the sides of the ship.

Sub Lieutenant Brown gave his report to Commander Hose, washed up, then took his station on the aft bridge. From the aft bridge wing he had a clear sight line along the rail, almost to the bow. He noted that the waves rolling along the ship’s side in this sea state almost topped over into the well deck. Consequently the shutters covering the secondary armament embrasures could not be dropped, lest the well deck turn into a swimming pool, and the 4.7 inch and 12 pounder guns could not be swung out. If it came to a fight in these conditions the Rainbow would only be able to use her two fore and aft 6 inch guns.

A messenger brought a wireless transcript to the bridge. RRR SS CORSICAN BEING ORDERED TO STOP BY CRUISER RRR. The message included a position off the west coast of Moresby Island.

Commander Hose looked at the message skeptically. He walked aft to the wireless cabin to consult. “Does the signal strength match the claimed position of the distress call?” he asked the wireless operator.

“It is not inconsistent,” the wireless operator responded. “We would be in a better position with a direction finding set.”

“That we would.” Replied Hose.

The wireless set came to life, and the operator transcribed the message. “Naval Code,” said the operator. He retrieved the current code book and decrypted the message.

DOMINION WIRELESS STATION DEAD TREE TO HMCD ESQUIMALT Y STATION DISTRESS MESSAGES FROM SS CORSICAN SENT BY SAME HAND AS PREVIOUS FALSE MESSAGES STOP MESSAGE IS ALSO MOST LIKELY FALSE STOP

“Surprise, surprise,” said Hose. The messages continued until the phantom Corsican announced her demise.

The day continued, sunny and windy. Periodically, Rainbow received messages of merchant ships being attacked by German cruisers, and the corresponding warning from Dead Tree Station, noting that these were most likely counterfeit. The original signal strengths diminished throughout the afternoon and evening as Rainbow made her way south. But the Dominion Wireless Service relays taunted even as the disk of the sun dipped to the horizon over the open Pacific.

At 2047 hours, Sub Lieutenant Brown on the after bridge, and Commander Hose on the wheelhouse starboard bridge wing, both gasped at the same time as the sun’s last ray dipped below the ocean’s surface and was refracted into that rarest of nautical phenomena, a green flash. To Rainbow’s stern, the Quatsino Sound Lighthouse on Kain's Island blinked. Directly to port, the unbroken wilderness of the Brooks Peninsula was still lit golden on its upper slopes. Some high cloud overhead glowed pink and purple. Tomorrow would be a clear sunny day.

Last edited: