1000 hours, SMS Princess Charlotte. Strait of Georgia, off Porlier Pass.

Von Spee and Radl looked from the Princess Charlotte’s bridge wing back through the pass they had just transited, between Valdez and Galiano Islands. The foremast of the sunken Marama jutted from mid channel, like a navigational hazard marker. And, in effect, it was.

“I had not intended us to end up on this side of these islands,” said Von Spee. “I was planning on taking us through Stuart Channel and behind all the islands in the gulf to arrive at Victoria by the back way. I got caught up in the chase.” He turned to enter the wheelhouse, to look at a chart, then stopped when he noticed Radl did not follow.

Radl remained looking back at Porlier Pass. “That passage is well and truly blocked. It will remain so after the port of Ladysmith is built back. We are at slack tide now, but the tide runs through this pass at up to seven knots, every six hours. They can’t put divers down in that current. The wreck will have to be broken up with explosives.” He stopped to consider the implications. “Until the wreck is cleared, that will add another 40 nautical miles one way for a coal barge travelling to Vancouver. Or a rail transfer barge. That is 5 or 6 hours for a barge under tow. Or more. Ladysmith is the only rail transfer point from Vancouver Island to the mainland. Rather than building back that transfer wharf we burned, the Canadians would be smart to build another somewhere else.”

“We had best travel south now,” Radl continued. “If you wish to get back into the waters between the gulf islands and Vancouver Island, we will have to enter by Active Pass, between Galiano and Mayne Islands. As will every other vessel, now that Porlier Pass is corked. Who knows, perhaps we will meet RMS Olympic in Active Pass and we can scuttle her there and plug that passage as well.”

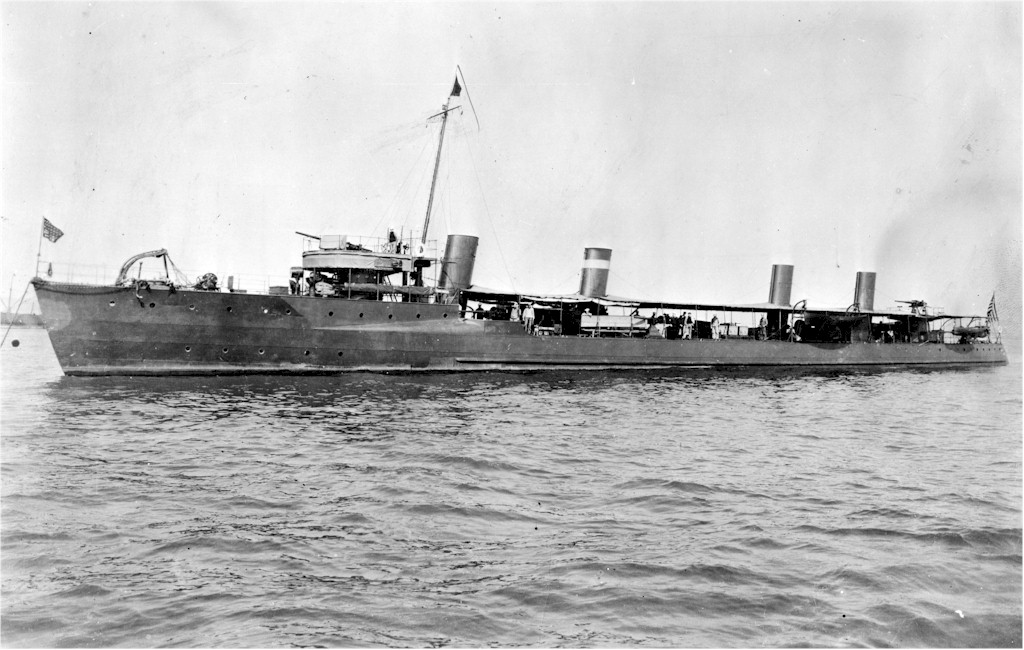

“Yes, south,” said Von Spee, distractedly. He had noticed smoke from a ship’s funnels to the east. “Take us south,” he ordered the bridge crew. “What is that ship there?” Radl looked through his binoculars. A coastal steamer with three funnels was running south down the middle of Georgia Strait, five miles distant.

“The Canadian Pacific Railroad liner Princess Victoria,” answered Radl. “Something of a rival to this ship.”

“She looks trim and fast,” said Von Spee.

“Yes,” Radl answered. “She is.”

“Will these coastal liners, like the one we are standing on, and that one there be used as troopships?” Asked Von Spee.

“Oh, certainly,” answered Radl “Bringing troops from Victoria and the coastal towns to the rail head in Vancouver. Recall the Princess Sophia.”

“Signals!” ordered Von Spee. “Send a challenge to that ship.”

STOP AND PREPARE TO BE BOARDED, sent the Princess Charlotte.

The reply from the Princess Victoria’s captain is as famous as it is unprintable.

Radl laughed long and hard.

Von Spee, blinked dramatically, and looked a bit put out. “Give us full speed,” he ordered, and the engine telegraph clanged.

“You will never catch that ship,” said Radl. “The Victoria is the faster ship, and her captain knows it.”

Von Spee ordered the Princess Charlotte up to full speed, and angled her course to intercept Princess Victoria. “Range!” Von Spee demanded.

“10,000 meters,” the gunnery officer answered.

“Well beyond the reach of our 5.2 cm guns,” said Von Spee disappointedly.

Princess Charlotte ran south east for 15 minutes, with the trees of Galiano Island lit golden by the mid morning sun to her starboard. The Princess Victoria was steering an almost identical course. The Germans did not seem to be gaining. Radl had never seen these waters so clear of shipping. Not even a fishboat was in sight, anywhere. Some smoke was showing to the south, past the Princess Victoria. The smoke looked to him to be in American waters, but at this distance it was hard to tell.

“Galiano Island,” mused Von Spee, as the minutes passed. “Was our patrol vessel named after the island?”

“Both were named after a Spaniard,” said Radl, “who visited here in the 18th century.”

“Range!” Von Spee asked the gunnery officer again.

“10,500 meters, sir,” the officer replied.

“Are we at maximum revolutions?” asked Von Spee.

The helmsman replied in the affirmative.

“Well,” Von Spee said. “That liner has a full knot on us.”

“I said…” replied Radl. “At her current speed and course, she will enter American waters within 15 minutes.”

“To be interned?” asked Von Spee.

“Unless she is carrying troops at the moment, she is a civilian vessel,” said Radl. “She is actually following her normal route right now, the Vancouver to Seattle to Victoria run. They call it the Triangle Route. So not interned. She can come and go as she pleases. But I suspect that passengers are not as eager to travel these waters of late.”

What is that smoke?” Von Spee asked. Radl raised his binoculars and looked to the south east, and Von Spee raised his own. After a moment he called “Lookout!” up to the foremast crow’s nest.

“Looks to be a patrol vessel, sir, painted white and flying the Stars and Stripes,” called down the lookout. “There is another, five miles further to the south, and more to the south east, close to the horizon, at least one, perhaps more.”

“Helm, five points to starboard,” ordered Von Spee. “We want to stay clear of the border, and we want anyone watching to notice that we are.”

“We will want to turn to the west in about six miles,” said Radl, “if you wish to turn back into the gulf island passages.”

Princess Charlotte continued steaming south east, until she slowed to enter Active Pass at 1035 hours. Looking to the east, the officers could see that the Princess Victoria had now crossed the maritime boundary, and looked to be having a vigorous exchange of semaphore with the American Patrol vessel. Von Spee could now read USRC Unalga on the American ship’s pristine white bow. To the south, a smaller, but no less brightly painted USRC Shawnee was approaching northward, right on the boundary line.

“That lighthouse marks the entrance to Active Pass,” said Radl, gesturing.

“Helm, turn for the passage,” ordered Von Spee. “Mister Radl, you have the bridge.”

Radl instructed the helmsman on his course changes through the S-bend of the pass, which narrowed to 500 metres in places. To the south, Mayne Island was heavily treed to the waterline, with a wide sandy bay midway through the pass sheltering a wharf and small settlement. To the north the shoreline of Galiano Island was also treed, but rockier, with cliffs and outcroppings of grey stone to the water’s edge, and fields of grass turned golden in the late summer heat. Homesteaders watched the German raider steam past, her German Naval Ensign flying high, from the shoreline and from small boats.

“What with the Princess Victoria, the lighthouse, the farmers, and the Americans,” said Von Spee, “I expect our position is being reported to the minute.”

The tide was beginning to turn, and ripples and eddies hinted at the volume of water moving through the narrow pass. With each course correction, a new vista opened up into small bays and coves, each looking, thought Von Spee suddenly, like a perfect spot for a submarine ambush.

“Lookouts!” ordered Von Spee. “Keep watch for periscopes.”

www.google.ca

www.google.ca

Von Spee and Radl looked from the Princess Charlotte’s bridge wing back through the pass they had just transited, between Valdez and Galiano Islands. The foremast of the sunken Marama jutted from mid channel, like a navigational hazard marker. And, in effect, it was.

“I had not intended us to end up on this side of these islands,” said Von Spee. “I was planning on taking us through Stuart Channel and behind all the islands in the gulf to arrive at Victoria by the back way. I got caught up in the chase.” He turned to enter the wheelhouse, to look at a chart, then stopped when he noticed Radl did not follow.

Radl remained looking back at Porlier Pass. “That passage is well and truly blocked. It will remain so after the port of Ladysmith is built back. We are at slack tide now, but the tide runs through this pass at up to seven knots, every six hours. They can’t put divers down in that current. The wreck will have to be broken up with explosives.” He stopped to consider the implications. “Until the wreck is cleared, that will add another 40 nautical miles one way for a coal barge travelling to Vancouver. Or a rail transfer barge. That is 5 or 6 hours for a barge under tow. Or more. Ladysmith is the only rail transfer point from Vancouver Island to the mainland. Rather than building back that transfer wharf we burned, the Canadians would be smart to build another somewhere else.”

“We had best travel south now,” Radl continued. “If you wish to get back into the waters between the gulf islands and Vancouver Island, we will have to enter by Active Pass, between Galiano and Mayne Islands. As will every other vessel, now that Porlier Pass is corked. Who knows, perhaps we will meet RMS Olympic in Active Pass and we can scuttle her there and plug that passage as well.”

“Yes, south,” said Von Spee, distractedly. He had noticed smoke from a ship’s funnels to the east. “Take us south,” he ordered the bridge crew. “What is that ship there?” Radl looked through his binoculars. A coastal steamer with three funnels was running south down the middle of Georgia Strait, five miles distant.

“The Canadian Pacific Railroad liner Princess Victoria,” answered Radl. “Something of a rival to this ship.”

“She looks trim and fast,” said Von Spee.

“Yes,” Radl answered. “She is.”

“Will these coastal liners, like the one we are standing on, and that one there be used as troopships?” Asked Von Spee.

“Oh, certainly,” answered Radl “Bringing troops from Victoria and the coastal towns to the rail head in Vancouver. Recall the Princess Sophia.”

“Signals!” ordered Von Spee. “Send a challenge to that ship.”

STOP AND PREPARE TO BE BOARDED, sent the Princess Charlotte.

The reply from the Princess Victoria’s captain is as famous as it is unprintable.

Radl laughed long and hard.

Von Spee, blinked dramatically, and looked a bit put out. “Give us full speed,” he ordered, and the engine telegraph clanged.

“You will never catch that ship,” said Radl. “The Victoria is the faster ship, and her captain knows it.”

Von Spee ordered the Princess Charlotte up to full speed, and angled her course to intercept Princess Victoria. “Range!” Von Spee demanded.

“10,000 meters,” the gunnery officer answered.

“Well beyond the reach of our 5.2 cm guns,” said Von Spee disappointedly.

Princess Charlotte ran south east for 15 minutes, with the trees of Galiano Island lit golden by the mid morning sun to her starboard. The Princess Victoria was steering an almost identical course. The Germans did not seem to be gaining. Radl had never seen these waters so clear of shipping. Not even a fishboat was in sight, anywhere. Some smoke was showing to the south, past the Princess Victoria. The smoke looked to him to be in American waters, but at this distance it was hard to tell.

“Galiano Island,” mused Von Spee, as the minutes passed. “Was our patrol vessel named after the island?”

“Both were named after a Spaniard,” said Radl, “who visited here in the 18th century.”

“Range!” Von Spee asked the gunnery officer again.

“10,500 meters, sir,” the officer replied.

“Are we at maximum revolutions?” asked Von Spee.

The helmsman replied in the affirmative.

“Well,” Von Spee said. “That liner has a full knot on us.”

“I said…” replied Radl. “At her current speed and course, she will enter American waters within 15 minutes.”

“To be interned?” asked Von Spee.

“Unless she is carrying troops at the moment, she is a civilian vessel,” said Radl. “She is actually following her normal route right now, the Vancouver to Seattle to Victoria run. They call it the Triangle Route. So not interned. She can come and go as she pleases. But I suspect that passengers are not as eager to travel these waters of late.”

What is that smoke?” Von Spee asked. Radl raised his binoculars and looked to the south east, and Von Spee raised his own. After a moment he called “Lookout!” up to the foremast crow’s nest.

“Looks to be a patrol vessel, sir, painted white and flying the Stars and Stripes,” called down the lookout. “There is another, five miles further to the south, and more to the south east, close to the horizon, at least one, perhaps more.”

“Helm, five points to starboard,” ordered Von Spee. “We want to stay clear of the border, and we want anyone watching to notice that we are.”

“We will want to turn to the west in about six miles,” said Radl, “if you wish to turn back into the gulf island passages.”

Princess Charlotte continued steaming south east, until she slowed to enter Active Pass at 1035 hours. Looking to the east, the officers could see that the Princess Victoria had now crossed the maritime boundary, and looked to be having a vigorous exchange of semaphore with the American Patrol vessel. Von Spee could now read USRC Unalga on the American ship’s pristine white bow. To the south, a smaller, but no less brightly painted USRC Shawnee was approaching northward, right on the boundary line.

“That lighthouse marks the entrance to Active Pass,” said Radl, gesturing.

“Helm, turn for the passage,” ordered Von Spee. “Mister Radl, you have the bridge.”

Radl instructed the helmsman on his course changes through the S-bend of the pass, which narrowed to 500 metres in places. To the south, Mayne Island was heavily treed to the waterline, with a wide sandy bay midway through the pass sheltering a wharf and small settlement. To the north the shoreline of Galiano Island was also treed, but rockier, with cliffs and outcroppings of grey stone to the water’s edge, and fields of grass turned golden in the late summer heat. Homesteaders watched the German raider steam past, her German Naval Ensign flying high, from the shoreline and from small boats.

“What with the Princess Victoria, the lighthouse, the farmers, and the Americans,” said Von Spee, “I expect our position is being reported to the minute.”

The tide was beginning to turn, and ripples and eddies hinted at the volume of water moving through the narrow pass. With each course correction, a new vista opened up into small bays and coves, each looking, thought Von Spee suddenly, like a perfect spot for a submarine ambush.

“Lookouts!” ordered Von Spee. “Keep watch for periscopes.”

Princess Victoria 1903

Passenger Ferry Princess Victoria Tahsis No 3 1903 Swan & Hunter Wallsend River Tyne

www.tynebuiltships.co.uk

Active Pass Lighthouse

Photographs, history, travel instructions, and GPS coordinates for Active Pass Lighthouse.

www.lighthousefriends.com

i-Boating : Free Marine Navigation Charts & Fishing Maps

fishing-app.gpsnauticalcharts.com

Google Maps

Find local businesses, view maps and get driving directions in Google Maps.

www.google.ca

www.google.ca