Aug 21, 1800 hours. SS Saxonia, Trevor Channel, Barclay Sound.

Sub Lieutenant Thomas Brown was satisfied that the tribulations this day had presented had been happily resolved, in his small corner of the world. The Saxonia’s infirmary had at noon been as busy as a big city hospital responding to a disaster. Between them, the Saxonia’s surgeon, the doctors from the town of Bamfield and the SS Tees, and their conscripted supporting staff of nurses, orderlies, lifeboat crewmen and German dining room waiters, had treated and stabilized the flood of 45 wounded. One of the Germans casualties had succumbed to a serious headwound, and been buried at sea, but the rest of the injured, German and Canadian, were resting comfortably. A few militiamen had even been discharged with arms in slings or on crutches.

The Cable Station in Bamfield to the east had burned to the ground, and the debris had fallen into the basement. This had finally burned out, and only small ribbons of smoke rose from the concrete foundation.

“I’m famished,” said Brown. “I think it is time have the kitchen and dining staff wash up and make some food for us and all the internees on this ship.”

“Prisoners of War,” corrected his commanding officer, the young Royal Navy Lieutenant who was serving as Saxonia’s prize captain.

“Prisoners of War?” said Brown, confused. “The waiters?”

“As an auxiliary to a naval ship,” said the Lieutenant pedantically, “Saxonia was operating as a warship, so her crew are Prisoners of War.”

Come suppertime, Brown released the Saxonia’s dining room staff from their jobs as medical attendants, and sent them to the galley to prepare a modest evening meal. Trays of ham sandwiches circulated throughout the ship. Eventually the waiters arrived at the bridge, and Brown happily grabbed a sandwich in each hand.

“Sauerkraut?” offered the waiter, raising a silver serving bowl.

“No thank you,” replied Brown.

Brown and the Lieutenant had been getting intermittent reports from the wireless set on the SS Tees, tied up alongside, since 1300 hours. The picture they painted was grim. Early in the day the reports were about the bombardment of Vancouver, Nanaimo and Ladysmith. Later in the day they documented attacks on Victoria and Esquimalt. Captain Hose and Rainbow had surprised the Germans off Esquimalt, and a battle had ensued, but the wireless had not reported the outcome.

At 1915 hours, Pacheena Point Dominion Wireless Station began to transmit a message.

ALL SHIPS ALL STATIONS 2 GERMAN CRUISERS WESTBOUND 10 MILES EAST OF PACHEENA LIGHT

Brown happened to be standing together with the Lieutenant at the foredeck gangway, when the runner from Tees delivered the message.

“There seems to be strong interference, all of a sudden,” reported the wireless runner, “but we are still receiving the Morse over top.”

“What do you make of this?” the Lieutenant asked Brown. “Would you guess the Hun are done with their spree? Or are they headed this way?”

“I would expect them to head straight out to sea,” considered Brown. “They have much to gain by fleeing now, and little to gain by staying. Isn’t Japan joining Britain in the war on the 23rd, in only two days time?”

“One day,” replied the lieutenant. Then he added, in response to Brown’s curious expression, “The International Date Line,”

“Could the German cruisers be coming here, to rendezvous with this very ship?” Brown asked, the thought just occurring to him.

“I am not convinced the Hun, the cruisers anyway, know this ship even exists,” said the Lieutenant. “When we first took possession of the bridge, and we had not rounded up all the crew, Saxonia’s captain and first officer had a confabulation. They thought they were speaking in hushed tones, but they underestimated my hearing. And I did not let on that I speak German.” Brown raised his eyebrows. “Well, they are merchant sailors after all,” the lieutenant scoffed. “It sounded like an eager local German diplomat in Seattle arranged to outfit Saxonia as an auxiliary on his own initiative, and had not contacted the ships at sea yet. He was worried his communications were being spied on. And apparently they were. The Saxonia was to contact the cruisers when she was well at sea. And failing that, meet up with the rest of the Hun’s East Asiatic Squadron, wherever they are.”

“When we chased Saxonia down, we jammed any wireless messages she tried to send,” said Brown. “Then the crew smashed her wireless, and threw all the codebooks over the side. If the cruisers somehow do know this ship has been fitted out as an auxiliary for them, they will not know where she is now.” The men looked out to sea, where the sunset was painting the western sky orange. Only a narrow slot of open ocean could be seen between Cape Beale and the islands guarding the west side of the inlet. Across the channel, the wreck of HMCS Malaspina was stranded partway up an otherwise beautiful beach, laying almost on her side.

The wireless runner brought notice that the warning from Pacheena Wireless Station was being repeated constantly, with the reported position of the German cruisers being updated from time to time, as they drew closer. And that the interference was growing stronger. Then, at 1945 hours the wireless operator on Tees reported a message in a different hand.

ABANDON WIRELESS STATION AM ABOUT TO DESTROY WITH GUNFIRE

Shortly after, the warning transmission from Pacheena Wireless Station ceased.

The suspense was lifted at 2020 hours, when a ship nosed past Cape Beale, and turned to enter Trevor Channel. The ship was a cruiser, flying the German Imperial Ensign. She appeared in this light entirely in silhouette, with her ensign dramatically back lit by the setting sun. The ram bow was exceptionally pronounced, almost a caricature, projecting forward into the waves at a 45 degree angle, which made the cruiser look even more alien and menacing, somehow.

Brown said, “We have been chasing these Germans up and down the coast for 4 whole days…”

“Almost 3 weeks for me,” interrupted the lieutenant.

“… and here they are coming right to us,” finished Brown.

SS Saxonia

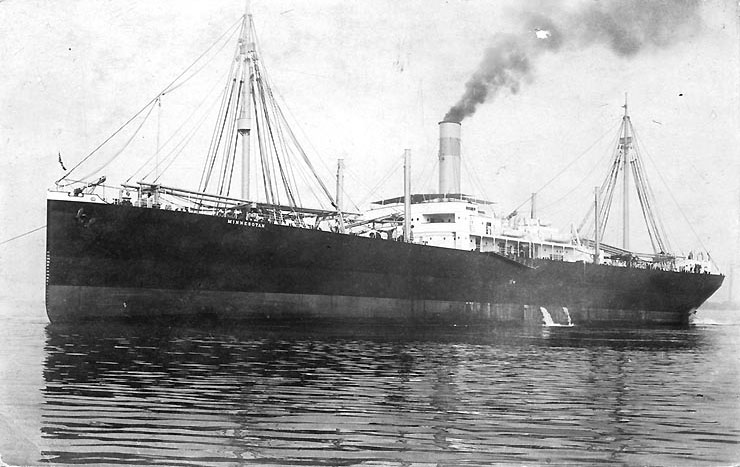

SS Tees

search-bcarchives.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca

search-bcarchives.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca

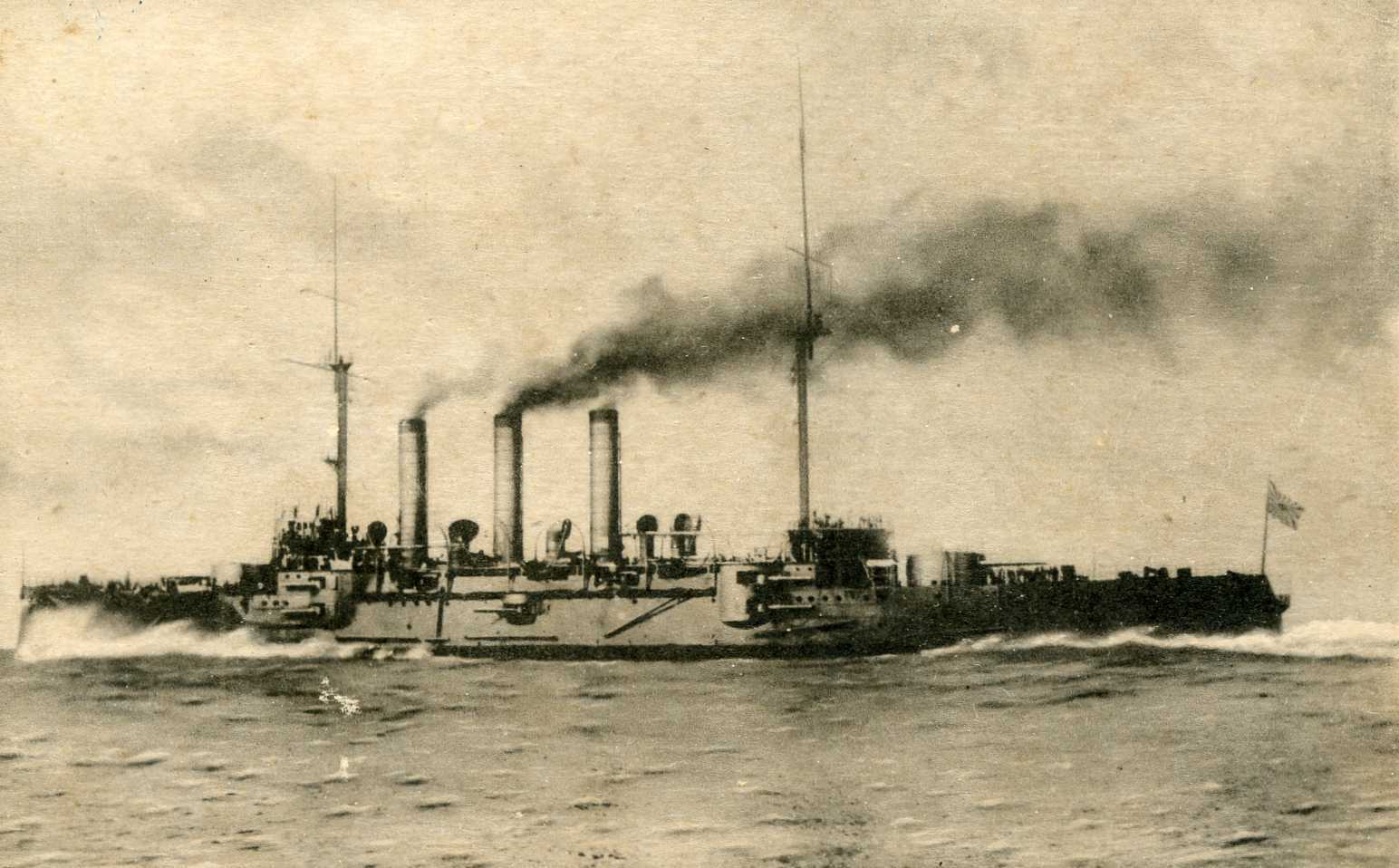

SMS Leipzig

www.deviantart.com

www.deviantart.com

Sub Lieutenant Thomas Brown was satisfied that the tribulations this day had presented had been happily resolved, in his small corner of the world. The Saxonia’s infirmary had at noon been as busy as a big city hospital responding to a disaster. Between them, the Saxonia’s surgeon, the doctors from the town of Bamfield and the SS Tees, and their conscripted supporting staff of nurses, orderlies, lifeboat crewmen and German dining room waiters, had treated and stabilized the flood of 45 wounded. One of the Germans casualties had succumbed to a serious headwound, and been buried at sea, but the rest of the injured, German and Canadian, were resting comfortably. A few militiamen had even been discharged with arms in slings or on crutches.

The Cable Station in Bamfield to the east had burned to the ground, and the debris had fallen into the basement. This had finally burned out, and only small ribbons of smoke rose from the concrete foundation.

“I’m famished,” said Brown. “I think it is time have the kitchen and dining staff wash up and make some food for us and all the internees on this ship.”

“Prisoners of War,” corrected his commanding officer, the young Royal Navy Lieutenant who was serving as Saxonia’s prize captain.

“Prisoners of War?” said Brown, confused. “The waiters?”

“As an auxiliary to a naval ship,” said the Lieutenant pedantically, “Saxonia was operating as a warship, so her crew are Prisoners of War.”

Come suppertime, Brown released the Saxonia’s dining room staff from their jobs as medical attendants, and sent them to the galley to prepare a modest evening meal. Trays of ham sandwiches circulated throughout the ship. Eventually the waiters arrived at the bridge, and Brown happily grabbed a sandwich in each hand.

“Sauerkraut?” offered the waiter, raising a silver serving bowl.

“No thank you,” replied Brown.

Brown and the Lieutenant had been getting intermittent reports from the wireless set on the SS Tees, tied up alongside, since 1300 hours. The picture they painted was grim. Early in the day the reports were about the bombardment of Vancouver, Nanaimo and Ladysmith. Later in the day they documented attacks on Victoria and Esquimalt. Captain Hose and Rainbow had surprised the Germans off Esquimalt, and a battle had ensued, but the wireless had not reported the outcome.

At 1915 hours, Pacheena Point Dominion Wireless Station began to transmit a message.

ALL SHIPS ALL STATIONS 2 GERMAN CRUISERS WESTBOUND 10 MILES EAST OF PACHEENA LIGHT

Brown happened to be standing together with the Lieutenant at the foredeck gangway, when the runner from Tees delivered the message.

“There seems to be strong interference, all of a sudden,” reported the wireless runner, “but we are still receiving the Morse over top.”

“What do you make of this?” the Lieutenant asked Brown. “Would you guess the Hun are done with their spree? Or are they headed this way?”

“I would expect them to head straight out to sea,” considered Brown. “They have much to gain by fleeing now, and little to gain by staying. Isn’t Japan joining Britain in the war on the 23rd, in only two days time?”

“One day,” replied the lieutenant. Then he added, in response to Brown’s curious expression, “The International Date Line,”

“Could the German cruisers be coming here, to rendezvous with this very ship?” Brown asked, the thought just occurring to him.

“I am not convinced the Hun, the cruisers anyway, know this ship even exists,” said the Lieutenant. “When we first took possession of the bridge, and we had not rounded up all the crew, Saxonia’s captain and first officer had a confabulation. They thought they were speaking in hushed tones, but they underestimated my hearing. And I did not let on that I speak German.” Brown raised his eyebrows. “Well, they are merchant sailors after all,” the lieutenant scoffed. “It sounded like an eager local German diplomat in Seattle arranged to outfit Saxonia as an auxiliary on his own initiative, and had not contacted the ships at sea yet. He was worried his communications were being spied on. And apparently they were. The Saxonia was to contact the cruisers when she was well at sea. And failing that, meet up with the rest of the Hun’s East Asiatic Squadron, wherever they are.”

“When we chased Saxonia down, we jammed any wireless messages she tried to send,” said Brown. “Then the crew smashed her wireless, and threw all the codebooks over the side. If the cruisers somehow do know this ship has been fitted out as an auxiliary for them, they will not know where she is now.” The men looked out to sea, where the sunset was painting the western sky orange. Only a narrow slot of open ocean could be seen between Cape Beale and the islands guarding the west side of the inlet. Across the channel, the wreck of HMCS Malaspina was stranded partway up an otherwise beautiful beach, laying almost on her side.

The wireless runner brought notice that the warning from Pacheena Wireless Station was being repeated constantly, with the reported position of the German cruisers being updated from time to time, as they drew closer. And that the interference was growing stronger. Then, at 1945 hours the wireless operator on Tees reported a message in a different hand.

ABANDON WIRELESS STATION AM ABOUT TO DESTROY WITH GUNFIRE

Shortly after, the warning transmission from Pacheena Wireless Station ceased.

The suspense was lifted at 2020 hours, when a ship nosed past Cape Beale, and turned to enter Trevor Channel. The ship was a cruiser, flying the German Imperial Ensign. She appeared in this light entirely in silhouette, with her ensign dramatically back lit by the setting sun. The ram bow was exceptionally pronounced, almost a caricature, projecting forward into the waves at a 45 degree angle, which made the cruiser look even more alien and menacing, somehow.

Brown said, “We have been chasing these Germans up and down the coast for 4 whole days…”

“Almost 3 weeks for me,” interrupted the lieutenant.

“… and here they are coming right to us,” finished Brown.

SS Saxonia

Submarine Tender Photo Index (AD)

www.navsource.org

SS Tees

The Canadian Pacific Railway's SS Tees. - RBCM Archives

RBCM Archives

SMS Leipzig