Chapter 190: Anglo-French relations: Harar High Noon

Art. V -- His Majesty the Emperor Menelek, King of Kings of Ethiopia, grants His Britannic Majesty’s Government and the Government of the Soudan the right to construct a railway through Abyssinian territory to connect the Soudan with Uganda.

A route for the railway will be settled by mutual agreement between the two High Contracting Parties.

The present Treaty shall come into force as soon as its ratification by His Britannic Majesty shall have been notified to the Emperor of Ethiopia.

In faith of which His Majesty Menelek II, King of Kings of Ethiopia, in his own name, and Lieutenant-Colonel John Lane Harrington, on behalf of His Majesty King Edward VII, King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of the British Dominions beyond the Sea, Emperor of India, have signed the present Treaty, in duplicate, written in the English and Amharic languages, identically, both texts being official, and have thereto affixed their seals.

Done at Adis Ababa, the 15th day of Many, 1902.

(L.S.) JOHN LANE HARRINGTON, Lieutenant-Colonel

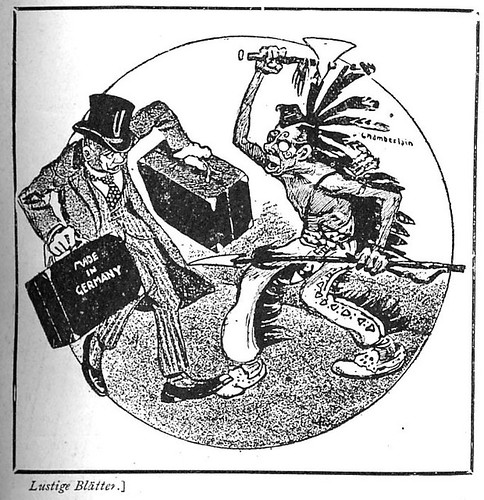

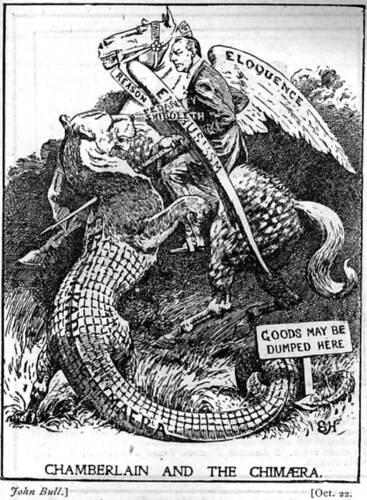

Harrington was just the type of bold and confident imperialist that Joseph Chamberlain liked to work with. Much to the dismay of Lansdowne, who wanted to ponder the general outlook of British foreign policy, Chamberlain cared a lot about how things currently looked like from the viewpoint of the common British voter.

Yes, yes, Mr. Delcassé and Mr. Camille Barrère kept talking, but events in Yunnan and Siam were clearly showing that the French clearly had conflicting colonial ambitions with Britain. Maxse, Strachey and Saunders and the rest of the press barons would have a field day in case the French would secure a railway monopoly in Ethiopia!

Chamberlain talked to Lansdowne, and Lansdowne talked to Harrington. Using the British creditors of the Compagnie Impériale des Chemins de fer d'Éthiopie as middlemen, Harrington met with Leonce Lagarde in Paris in early December 1903.

Initially they seemed to find a common way ahead. The French would control the line to the point it was currently built. The future part of the line would be operated jointly, just like the Baghdad Railway, and Djibouti would become a free port for international trade with Ethiopia. This would prevent King Menelik from playing the two powers against one another.

And to keep both sides honest, they would jointly guarantee the independence of Ethiopia.

Lord Cromer was keenly following the news from Egypt, and soon chimed in - he wanted to include Italy to the bargain. He knew the proposals the Italians had made to Sir James Rennell Rodd, his former second-in-command, who was currently posted to the British Embassy in Rome.

Rennell Rodd had reported that Giacomo Agnesa, head of the colonial section of the Italian foreign service, had approached him with a set of preliminary recommendations for a joint Anglo-Italian policy in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa, with the impression that HM's Government would be willing to negotiate "as Sir Harrington conveyed to us."

Not showing any visible confusion, Rennell Rodd had played along. The final agreement from these discussions was that both sides should publicly be committed to maintaining Ethiopian independence. But, Agnesa had argued, they should also make sure that "any unnamed other power" should not be allowed to jeopardize Italian and British interests in case of a collapse of Ethiopia.

A plan for a joint anti-French policy with Italy the week before, a proposal for cooperation with the French a week later. Harrington liked to bet and plan for several possible outcomes at the same time.

By January 1904 Harrington preferred the first option. He told Lord Cromer that he was willing to do his utmost to defeat the French railway plans. Cromer replied that a railway in Ethiopia would not be worth risking a conflict over.

At the same time governor Lagarde told to the French colonial lobby in Paris that a condominium over the Djibouti railway would negate exclusive French dominance over the food producing hinterland of Ethiopia which he considered essential to the development of the adjacent colony of Djibouti - which he had himself established and led earlier on.

Lagarte knew that the French government had committed public funding to the company, and he urged the Ethiopians to proceed to finish the line without British interference. Meanwhile Joseph Chamberlain had just managed to rally his government to sign the Baghdad Railway deal despite the press war against it, and now could not afford to appear making a similar appeasing move with another competing colonial power right before the looming general election.

Last edited: