Thanks for the kind words. Many people much better versed to the intricacies of British foreign politics have compared the present issues to these OTL events. But I'll leave that topic to Chat, for obvious reasons. Since now the Liberals have to decide what they actually want, and how they want to achieve it.I love this TL so much.

And just in case we needed more corroborating evidence that fin de siecle is eerily similar to the present: not only does the bread loaves stunt look like something out of a contemporary, "the wells are poisoned" election campaign, but the newspapers' reactions basically look like memers shitposting on social media. Incredible.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Chapter 197: Britain, Part XX: "No. There is another."

However, C-B himself was wary of taking on the strain of leading the government from the front bench in the House of Commons. His closest friends and supporters, including John Morley, warned him against it. Years earlier he had let it be known that he did not wish to “take any part which involved heavy and responsible work”, implicating that he would be content with a peerage and an honorific position, perhaps Lord President. The main reason for his reluctance was personal: his beloved wife had been in poor health for years now.[1]

He also had powerful opponents. Asquith had been a leading candidate for the party leadership in 1898, and only personal financial reasons had forced him to yield the chair to C-B. Asquith had also previously held Cabinet office, and was widely praised for the way he had hounded Joseph Chamberlain on the campaign trail through the country. Constructing a reliable Liberal government without him would be exceedingly difficult.

And to complicate matters further, Asquith was part of the Liberal Imperialist faction that had rallied around the political positions of Lord Rosebery. He, Sir Edward Grey and Richard Haldane had not given up the Liberal Imperialist position adopted by Rosebery. The memory of the Boer War was still a bitter divide between these men and the Liberal opponents of the conflict, and they and had a plan to defy C-B and his perceived dovish positions in foreign policy.

The three men had concluded an arrangement known as “The Relugas Compact”, hoping to force Campbell-Bannerman to effectively retire to the Lords and cede the actual power in the party and government to them to divide as they pleased. This internal opposition threatened to open old wounds. The party had won the elections by campaigning on a negative basis - against the Imperial Preference and for the Free Trade - but beyond that there were strong internal divisions that would have to be healed and mended.

Besides, being leader of the opposition did not confer an automatic right of succession to the premiership. His fierce criticisms of the Boer War had earned Henry Campbell-Bannerman the disdain of King Edward VII.[2]

Whitehall, while weary of overstepping the political boundaries and customs, made it indirectly known through the royal entourage that there was another Liberal who would be preferable as the new Prime Minister in the eyes of the Crown. This was something the man in question and Henry Campbell-Bannerman had anticipated well in advantage. Being old friends and political allies, they already had a plan for this eventuality.

1: All OTL. Campbell-Bannerman was well aware of the plotting against him, but his public statements of modesty were not all about politics, since he and his friends really worried about his health .

2. The King does not travel to Marienbad like in OTL because of his permanent hip injury and disdain of the Continent, and thus C-B does not have a chance to meet him there and impress him.

Driftless

Donor

I'll confess a large dose of ignorance of British politicos, especially in that era. Any hints? Or, do we need to be patient?Whitehall, while weary of overstepping the political boundaries and customs, made it indirectly known through the royal entourage that there was another Liberal who would be preferable as the new Prime Minister in the eyes of the Crown. This was something the man in question and Henry Campbell-Bannerman had anticipated well in advantage. Being old friends and political allies, they already had a plan for this eventuality.

Hmm. I don't know enough about C-B, really.

Not Dilke. Even if he had the reputation, I don't think C-B liked him.

Ripon's probably too old. Loreburn's opposed to Liberal Imperialism and the Entente, but isn't that interesting a character.

Crewe, maybe? Friend of Asquith, son-in-law of Rosebery, but had worked hard to avoid the South African War and worked well with CB. Or Morley- a Liberal who opposed workplace reforms, might make a good foil if Karelian's setting Chamberlain up to realign the parties permanently.

Not Dilke. Even if he had the reputation, I don't think C-B liked him.

Ripon's probably too old. Loreburn's opposed to Liberal Imperialism and the Entente, but isn't that interesting a character.

Crewe, maybe? Friend of Asquith, son-in-law of Rosebery, but had worked hard to avoid the South African War and worked well with CB. Or Morley- a Liberal who opposed workplace reforms, might make a good foil if Karelian's setting Chamberlain up to realign the parties permanently.

Last edited:

He was the person Gladstone was prepared to suggest as his successor when he went to visit Victoria - who didin't ask for his opinion and chose Rosebery instead.I'll confess a large dose of ignorance of British politicos, especially in that era. Any hints? Or, do we need to be patient?

He especially benefits from the earlier elections.

No one from this list, even though these are good guesses, and names we will meet later on.Hmm. I don't know enough about C-B, really.

Not Dilke. Even if he had the reputation, I don't think C-B liked him.

Ripon's probably too old. Loreburn's opposed to Liberal Imperialism and the Entente, but isn't that interesting a character.

Crewe, maybe? Friend of Asquith, son-in-law of Rosebery, but had worked hard to avoid the South African War and worked well with CB. Or Morley- a Liberal who opposed workplace reforms, might make a good foil if Karelian's setting Chamberlain up to realign the parties permanently.

Oh.

Ha.

Poor Ireland. Joe on the one hand, the murderer of Maolra Seoighe on the other. I mean, he talked a good game on Home Rule later, but still....

Ha.

Poor Ireland. Joe on the one hand, the murderer of Maolra Seoighe on the other. I mean, he talked a good game on Home Rule later, but still....

The man of many qualities.Oh.

Ha.

Poor Ireland. Joe on the one hand, the murderer of Maolra Seoighe on the other. I mean, he talked a good game on Home Rule later, but still....

He is also a former First Lord of the Admiralty and one of the founders of the original National Rifle Association.

Driftless

Donor

Well, wasn't W S Churchill a Liberal MP at the time (or later?) and a later Lord of the Admiralty, but isn't he's pretty young at this point? Of course, maybe some of the senior politicos see that as him being easier to manipulate to an extent, as boggling a thought as that is?The man of many qualities.

He is also a former First Lord of the Admiralty and one of the founders of the original National Rifle Association.

Well, wasn't W S Churchill a Liberal MP at the time (or later?) and a later Lord of the Admiralty, but isn't he's pretty young at this point? Of course, maybe some of the senior politicos see that as him being easier to manipulate to an extent, as boggling a thought as that is?

The March of Time - 20th Century History

Well that's a great way to get @'ed :p Hahahaha, if it weren't, there would be no need for me to ask not to get tagged, after all x'Dx'D But in all seriounsess: there are multiple great Entente-victory TLs on this site (Salvador here is authoring one himself), whereas the "Germany does better...

www.alternatehistory.com

Chapter 197: Britain, Part XXI: Foxy Jack

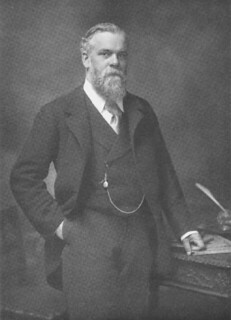

A lean, lanky figure, known for both of his patient courtesy and authoritative keenness.

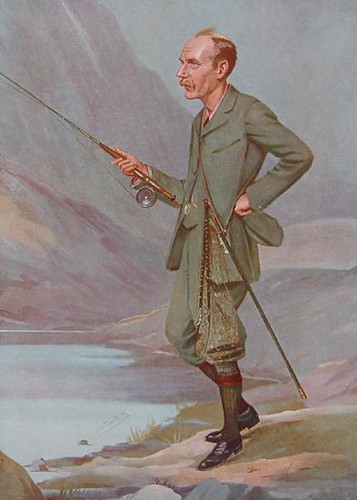

He frequented stables, kennels and politics. He was the man Gladstone was prepared to propose as his successor when the great Liberal premier had attended the Queen to present his formal resignation.

Lord John Poyntz Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer, loyal as the foxhounds he so loved, had then followed Gladstone to opposition and societal isolation over the question of Home Rule.

He and Henry Campbell-Bannerman had joined forces when CB worked as Lord Spencer’s Chief Secretary. The two men got along well. CB earned his political spurs by building up positive image among the Irish MPs, while his despised superiour drew their criticism.

Spencer also served as shield for Gladstone, stamping out dissent and earning a reputation as a hangman and sodomite among the Irish nationalists while Gladstone courted the Irish MPs at Westminster.

Ever since that time Spencer and CB had kept in touch, visiting one another and exchanging letters, discussing tactics and envisioning the structure and politics of a potential Liberal government.

As a successor of Lord Kimberley as the Liberal leader in the House of Lords, Earl Spencer had been more or less preordained to serve as the next Prime Minister from the start. He was acceptable enough for the King (having served in the council of the Prince of Wales from 1898 to 1901), as well as Radicals and Liberal Imperialists alike.

He had also chosen his key political ally well. CB liked to play the role of an jolly and kind old Scottish uncle, totally out of his depth in the hard world of Westminster.

In reality he was a shrewd political cutthroat, well able to discover and ruthlessly exploit the weaknesses of his would-be foes. He had not defeated Rosebery and Asquith by accident.

After the election results were clear, he stated to Spencer that the Relugas trio was merely bluffing. They could never go over to the Unionists because of the free trade issue, and would neither allow Joe Chamberlain to return to power by splitting the party. And as it turned out, he was right. Two out of the three could be easily placated, and that turned out to be enough for Spencer and his future government.

Chapter 198: Britain, Part XXII: Who do you serve and who do you trust?

Distinguishes the swift, the slow, the subtle,

The housekeeper, the hunter, every one

According to the gift which bounteous nature

Hath in him closed, whereby he does receive

Particular addition, from the bill

That writes them all alike. And so of men.

- Macbeth, Act 3 Scene 1

Lord Spencer and Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman knew that more than anything, H. H. Asquith desired power. The leader of the Relugas plot was notorious for his vanity.

So Spencer approached Asquith with open arms, and full of praise. Ignoring rumours of political backroom backstabbing, Lord Spencer stated that the country needed experienced Liberals at this critical hour. Therefore he wanted to appoint Asquith as the new Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Having secured his acceptance for this position rather easily, Spencer and CB had split the ranks of their internal opposition - and could now dictate terms to the remaining would-be rebels.

They were also aware of the qualities of Haldane, a loyal old friend of Asquith. Unlike Asquith, Haldane was more interested in ideas and their implementation rather than actual power itself.

He was a Hegelian in outlook, and preferred systems that were led and organized like a well-designed machine, dealing with sound ideas that were well thought-out.

A firm proponent of efficiency, coordination and scientific principles, he was a man of many talents. He was also caught completely flat-footed by the betrayal of the compact he had made with Asquith and Grey, and was thus not in a position to negotiate terms.

Much to the surprise of Haldane, Lord Spencer made it known - immediately after Asquith had yielded - that the tasks of the next President of the Board of Education demanded immediate attention.

Furthermore, the new Prime Minister was of the mind that the much-needed reorganization of British education system would be a task worthy of a scholar such as Haldane.

Overwhelmed by sudden turn of events and the opportunity presented for him, Haldane humbly accepted his new post:

These moves were less magnanimous than they initially appeared. Lord Spencer knew that he needed Asquith for the trials his government would face because of its dependence on the support of the Irish MPs.

He called Asquith and Haldane to serve in posts that would expose both men to certain criticism from the opposition and the press. But he would not grant the three "Limps" everything they had wished for.

Having brought his political enemies close, lord Spencer intended to use their talents to implement an agenda that different from their political vision in many areas: constitutional reform and social politics.

CB and Spencer knew that even after the Boer War, foreign policy was still the most controversial topic within the Liberal ranks. Spencer and CB had effectively isolated his strongest rival, Lord Rosebury, during the election campaign.

Now they now did the same to the trio that had supported him. The aloof but prominent foreign policy voice within the Liberal party, Sir Edward Grey, was now sidelined. This was intentional, because Spencer had other options in mind as the next head of the Foreign Office.

1: This was apparently true in OTL as well. In OTL CB was able to promote the careers of his Scottish radical allies such as Lord Loreburn. Spencer has less need for this, and prefers to place Haldane to a position that matches his previous political skills.

Last edited:

Chapter 199: Britain, Part XXIII: The Silent Earl

The post Lord Spencer wanted to fill was vitally important. Joseph Chamberlain and Lansdowne had led an active foreign policy, and the international situation was full of tension and uncertainty in spring 1904. The Tory and Unionist election propaganda of Liberals as unreliable and wobbly in foreign policy was potential poison for the long-term vitality of the new government.

Therefore Lord Spencer carefully considered his potential options. He had a long list of candidates, but only a token few were chosen for closer consideration. Many were politically damaged goods: Charles Dilke had never recovered from the adultery case that destroyed his public image.

Therefore Lord Spencer carefully considered his potential options. He had a long list of candidates, but only a token few were chosen for closer consideration. Many were politically damaged goods: Charles Dilke had never recovered from the adultery case that destroyed his public image.

One of them was a former Under-Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and a Gladstonian humanitarian activist to boot. James Bryce was both a historian and a politician, and an intellectual who had personally visited most of the trouble-spots of Empire.

He had the habit of travelling around the world, and visited his constituents in Aberdeen only for three or four days a year! He had toured the Balkans, authored a book about the Armenian territories of the Ottoman Empire, and went to mountaineering trips to the Continent annually. He was sixty-six, but still in excellent health and physique, with seemingly inexhaustible energy.

As an Scots-Irish of Ulster by birth, he was convinced that Home Rule for Ireland was necessary - but namely because how badly the Irish Question affected the American image of Britain across the Atlantic!

Another potential name for the post was was widely seen as the main representative of the Gladstonian tradition. He was a devoted free-trader who had loyally supported Campbell-Bannerman and his moderate line during the years in opposition when the Rosebury and the Liberal Imperialists had tried to undermine him. As a person he was ambitious - but also vain, proud, oversensitive man who found failure frustrating. He had been in politics for so long that Joseph Chamberlain was his former close friend and mentor from days before the Unionist split.

Another potential name for the post was was widely seen as the main representative of the Gladstonian tradition. He was a devoted free-trader who had loyally supported Campbell-Bannerman and his moderate line during the years in opposition when the Rosebury and the Liberal Imperialists had tried to undermine him. As a person he was ambitious - but also vain, proud, oversensitive man who found failure frustrating. He had been in politics for so long that Joseph Chamberlain was his former close friend and mentor from days before the Unionist split.

The Irish Nationalist leaders also viewed him as their de facto spokesman. John Morley had indeed many good qualities.

The main problem with him was that he was controversial within the party, a fact that he was both firmly aware and outright proud.

The free trade question had turned Morley from an isolated old advocate of an unfashionable, even unpatriotic cause to one of the natural leaders in the campaign to defend free trade orthodoxy almost overnight.

But did he really want to return to a leading role in parliamentary politics? There were few surviving colleagues to whom Morley had any real personal contact, and he despised the way the rising cadre of Liberal Imperialists had behaved towards Campbell-Bannerman.

He and Spencer knew one another from the days of the parliamentary committee of the Home Rule bill, but they were not close.

And then there was the third option.

And then there was the third option.

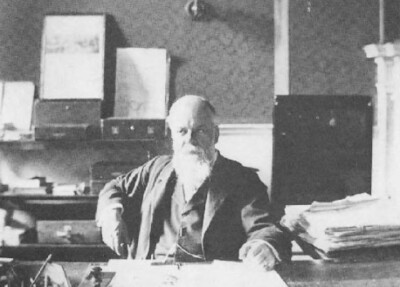

He was much admired by the other Scottish liberals, including CB, who had known him for a long time as an industrious "safe pair of hands."

He was never happy in London society, and preferred vigorous outdoor life in Scotland to socializing, although he disliked hunting and focused on archery, cricket and curling.

He kept meticulous accounts of expenditure. He habitually recorded the reasoning behind his decisions, and refused to have a telephone at his home “lest he should commit himself on the spur of a moment.”

He had a high sense of seriousness and duty, and this feature kept him getting back into the service of the state against his own better inclination. He was a family man, with eleven children.

He also had a talent for negotiation and as a chairman. As a person he was unassertive, calm, quiet, not saying too much himself, showing that he understood and appreciated the necessities of others.

His youth had been imperial in the best sense of the word. His father had been the governor of Jamaica, governor general of Canada, envoy to China and Viceroy to India.

He was born in Canada, but had been educated at Glenalmond, Eton and Balliol. He had risen into a position of a prominent imperial figure within the Liberal Party. His most recent political work had been the chair of the Royal Commission appointed in 1902 to report on the military preparations for the Boer war. He secured an unanimous report presented in July 1903.

As a former Viceroy of India his credentials and reputation were such that Grey had no objection to see him as as the new Foreign Secretary.[1]

Personally he would have wanted the Scottish Office or the War Ministry - but when cajoled by CB and Spencer, he dutifully heeded their call for help. When Lord Spencer announced his name as the new Foreign Secretary, the Times wrote that “no other Liberal was equipped to meet foreign statesmen and ambassadors on equal terms."

And thus Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, would soon create himself a reputation as a notably cautious, sensible, if self-effacing Foreign Secretary. Events of the coming years would make him one of the busiest ministers of the government of Lord Spencer.

1: Unlike the two others. In OTL and in TTL Grey had most influence within the party through his impact on the Commons. Even when isolated from his friends and co-conspirators, his views still matter because of party factionalism and the narrow majority position Spencer finds his government in.

One of them was a former Under-Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and a Gladstonian humanitarian activist to boot. James Bryce was both a historian and a politician, and an intellectual who had personally visited most of the trouble-spots of Empire.

He had the habit of travelling around the world, and visited his constituents in Aberdeen only for three or four days a year! He had toured the Balkans, authored a book about the Armenian territories of the Ottoman Empire, and went to mountaineering trips to the Continent annually. He was sixty-six, but still in excellent health and physique, with seemingly inexhaustible energy.

As an Scots-Irish of Ulster by birth, he was convinced that Home Rule for Ireland was necessary - but namely because how badly the Irish Question affected the American image of Britain across the Atlantic!

The Irish Nationalist leaders also viewed him as their de facto spokesman. John Morley had indeed many good qualities.

The main problem with him was that he was controversial within the party, a fact that he was both firmly aware and outright proud.

The free trade question had turned Morley from an isolated old advocate of an unfashionable, even unpatriotic cause to one of the natural leaders in the campaign to defend free trade orthodoxy almost overnight.

But did he really want to return to a leading role in parliamentary politics? There were few surviving colleagues to whom Morley had any real personal contact, and he despised the way the rising cadre of Liberal Imperialists had behaved towards Campbell-Bannerman.

He and Spencer knew one another from the days of the parliamentary committee of the Home Rule bill, but they were not close.

He was much admired by the other Scottish liberals, including CB, who had known him for a long time as an industrious "safe pair of hands."

He was never happy in London society, and preferred vigorous outdoor life in Scotland to socializing, although he disliked hunting and focused on archery, cricket and curling.

He kept meticulous accounts of expenditure. He habitually recorded the reasoning behind his decisions, and refused to have a telephone at his home “lest he should commit himself on the spur of a moment.”

He had a high sense of seriousness and duty, and this feature kept him getting back into the service of the state against his own better inclination. He was a family man, with eleven children.

He also had a talent for negotiation and as a chairman. As a person he was unassertive, calm, quiet, not saying too much himself, showing that he understood and appreciated the necessities of others.

His youth had been imperial in the best sense of the word. His father had been the governor of Jamaica, governor general of Canada, envoy to China and Viceroy to India.

He was born in Canada, but had been educated at Glenalmond, Eton and Balliol. He had risen into a position of a prominent imperial figure within the Liberal Party. His most recent political work had been the chair of the Royal Commission appointed in 1902 to report on the military preparations for the Boer war. He secured an unanimous report presented in July 1903.

As a former Viceroy of India his credentials and reputation were such that Grey had no objection to see him as as the new Foreign Secretary.[1]

Personally he would have wanted the Scottish Office or the War Ministry - but when cajoled by CB and Spencer, he dutifully heeded their call for help. When Lord Spencer announced his name as the new Foreign Secretary, the Times wrote that “no other Liberal was equipped to meet foreign statesmen and ambassadors on equal terms."

And thus Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, would soon create himself a reputation as a notably cautious, sensible, if self-effacing Foreign Secretary. Events of the coming years would make him one of the busiest ministers of the government of Lord Spencer.

1: Unlike the two others. In OTL and in TTL Grey had most influence within the party through his impact on the Commons. Even when isolated from his friends and co-conspirators, his views still matter because of party factionalism and the narrow majority position Spencer finds his government in.

Last edited:

Chapter 200: Britain, Part XXIV: New Hounds for the Hunt

The way the Spencer cabinet took shape had a lot to do with the way the Liberal Party leadership worked. Now, formally things were simple enough. Earlier on both the Peers and MPs had each elected a leader in their own House.

In practice this meant that the informal cliques had already made the necessary arrangements at the backrooms of the National Liberal Club, and then presented a single candidate to the Parliament and another to the House of Lords.

The vote in the latter institution had been a rather simple affair. The Liberal Peers led by Lord Spencer had only Kimberley and Ripon left as the most notable still active politicians with former senior office experience from the days of Gladstone.

In total there were roughly only a dozen or so Peers left from the mass defections to the Unionist camp. The Commons had a similar situation: CB was one of only four ex-cabinet ministers still active in the front-row politics.

Only someone appointed a Prime Minister could claim to have overall authority over the party in both Commons and Lords. In practice the monarch could only select someone who had the support of the party leadership. Here matters were clear, as Spencer and CB were in agreement of their roles in the upcoming government.

With only a token few old colleagues left to choose from, Lord Spencer was therefore more or less forced to pick from a handful of potential candidates to fill his government posts. Here party politics entered into the equation.

Last edited:

Chapter 201: Britain, Part XXV: Old Huntsman, New Pack

In practice he could not just appoint anyone he wished to. The appointees had to have the ability to defend policies in parliament, and therefore route existed: first gaining a reputation through effective performance in a junior office before gaining more demanding positions.

The whips office of the Liberal Central Association also had a say to the matter: the chief whips were remarkably efficient using efficient mixtures of rewards, threats and cajoling to keep their ducks in a row.

As some positions were thus handed out by the whips as rewards for former loyalty, or appointments designed to balance the party factions and interest groups, the cabinet forming around the prime minister was mainly a balancing act of contending factions and sections of the Liberal Party.

Personal preference overrode the desire to re-appoint all of the surviving cabinet of 1895. "The wilderness” in opposition since the previous decade meant that Spencer more or less had to appoint men without prior government experience to his cabinet.

He nevertheless wanted dedication, and demanded his cabinet ministers to relinquish their company directorships on taking up their posts.[1] As it was, he also had to leave many old Peer confrères to the sidelines for a well-earned political retirements: many potential candidates like Ripon, Wolverhampton and Carrington were all simply too old for the tasks and trials that lay ahead.

The men Spencer chose had a lot in common. While the new cabinet contained many professional middle class lawyers, writers, and a token few journalists, landlords were still the most over-represented group.

Nevertheless the new cabinet consisted of men who knew one another rather well. The Liberal MPs formed wide networks. Many had close relatives who were or had been MPs as well. Business enterprises, shared charities and religious denominations created relationships that bound them together.

All cabinet ministers were equal, but some were more equal than others: the Postmaster-General had less clout than the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Ministers could raise any points they wished, and the resulting debates were often exhausting, when seniority and former achievements played against energy and debating tenacity of the younger members. The debates were important, since there was never any such thing as an overall pre-mediated Liberal strategy that was to be followed in every ministry.

The Prime Minister was certainly a leader, but not a dictator with sweeping powers. There was no cabinet secretary, and no fixed agenda. Theoretically the Prime Minister had the power to overturn decisions and make up the mind of the government, even against the majority of the other ministers.

In reality he could never stand alone against his whole cabinet.

As a result the ministers had more or less a free reign to run things in their own departments as they thought fit, until it was time to bring major legislation to the cabinet, or until they met some political obstacle they couldn’t deal with by themselves.

The cabinet met usually only once per week, and most ministers were too busy with their own work to pay close attention to the work of their colleagues. Thus they often had little in the agenda to argue about, and often matters were agreed informally before they were officially debated and discussed.

Naturally all ministers had their likes and dislikes, but there was little personal enmity aside from CBs lasting, but manageable dislike for Haldane. Thus the political disputes were manageable and kept within the cabinet, that was able to display the vitally important political unity to the opposition and media.

1: As per OTL

Last edited:

Chapter 202: Britain, Part XXVI: Peace, Retrenchment and Reform?

Their attitudes towards the Irish Nationalism and Labour were complicated. Deep down the Liberals thought these two movements as useful, but troublesome auxiliary forces in their righteous struggle.

From this it followed that they considered the other political forces in British society movements to have a moral duty to rally to their cause to defeat Conservatism together.

But the existence of these forces had disturbing implications: that the workers had interests opposed to those of the rest of the society, and that the Irish nationalism was in conflict with the rest of the United Kingdom.

Despite finding these premises unacceptable in theory, the Liberals were in practice quite ready to allow the Labour MPs to represent the trade unionist point of view in matters involving workplace relations, and to acknowledge that the Nationalists were representing the political views of the Irish people.

The Conservatives were the enemy that united the party, and thus Liberalism was not anti-Nationalist or anti-trade union in essence.

The goals of direct taxation and welfare reforms were pursued with the careful aim of avoiding penalizing the middle class in the process. The long-cherished goals of ending the Lords’s veto and securing Home Rule also united the cabinet, even though there were disagreements of the methods and preferable final outcomes of these more ambitious aims.

Here the political factionalism of Liberals was again present.

Armament expenditure and social reform, especially the issue of unemployment, were both a source of protests.

The “awkward squad” of 25-30 MPs who wanted to press on faster with social reform were theoretically strong enough to deflect cabinet policy in alliance with the Labour MPs. But defeating a Liberal government from within was unthinkable when the alternative was the jingoist Tory administration. Thus the rebels remained on the sidelines.

This kept the would-be dissenters and factions leaderless and internally divided. Besides, the backbenchers were generally terrified of the Chamberlainite alternative. And while less threatening than it seemed, the dissent was constant: the government was always deemed to be either too hesitant or too radical in the pursuit of Liberal ideas and agenda.

Last edited:

Chapter 203: Britain, Part XXVII: Liberals and the world

Earl Elgin and Lord Spencer had the ungrateful task of trying to balance the general guidelines of the foreign policy of their cabinet between the Liberal imperialists and the Radical wing of their party.

Willingness to be on good terms with all nations and to promote international harmony made the Radicals more or less impossible to please.

Spencer was convinced that the previous election had once again shown that the common voter cared little about far-away lands outside of the British Empire, and he wanted to focus on domestic matters. Meanwhile the minority interests of the Radicals kept making a lot of noise at the Commons about foreign policy, before finally falling in line when the alternative was to see the cabinet lose a vote of confidence.

In Great Power relations the Radicals were increasingly at odds with themselves. This was further complicated by the fact that the Radicals were a loose conglomerate of generally like-minded individuals, not a coherent political group with a leader and an agreed-upon agenda.

They were generally cynical in their approach to the world of cabinet diplomacy to begin with. Idea of elite conspiracy vs the good intentions of the "common people" was appealing for many of them.

They detested professional diplomats, and often argued that the "governing class" was determined to keep playing their diplomatic games of balance of power while hiding foreign policy away from parliamentary scrutiny.

They were in principle against every kind of foreign commitment and alliance - but should these be found necessary for British interests, they preferred the idea of cooperation with France, whose political system was more humane than the autocratic repression found from Germany and Austria-Hungary.

At the same time some of them liked Germany, some abhorred her, while very few had any first-hand experience of Germany to begin with. Some held the idea that Germany was being ‘penned in’ - and these people were sometimes at the same time favor of closer relations with France!

While they generally detested Russia as an oppressive, intolerant autocracy of barbaric, uncivilized Slavs, they still regarded the Russian Empire higher than the openly reviled Ottoman Empire, where the plight of Armenians and the chaos of Macedonia was a favourite topic of many Radical MPs.

Ultimately more of a background noise rather than a force coherent and coordinated enough to actually guide British foreign policy, the Radicals nevertheless indirectly affected the way the Spencer cabinet dealt with the crises of 1905.

Last edited:

Chapter 204: Britain, Part XXVIII: Casting Arc

The shadow of Joseph Chamberlain loomed large over the Colonial Office when the Liberals took over. The aftermath of "Joe's War" and the other pressing colonial questions of the day clearly required cabinet attention. Liberal Imperialists and the rest of the party were at odds on what would be the best colonial policy - and who exactly would be acceptable as the next Secretary of State for the Colonies?

Lord Spencer chose a compromise candidate who had the right pedigree, former experience and views that were more or less acceptable for every faction.

The new head of the Colonial Office was grandson of a man who had carried on the work of the great Wilberforce in leading the campaign against slavery.

He had started his political career at the age of thirty, and had immediately demonstrated ample political acumen. His book of arguments about the pros and cons of the key political debates of Britain had sold well, considering that it had been written by a man who had reached Westminster only two years ago.

He was a socialite, well-liked for his informal manners and sharp wit. Politically he had avoided the pitfalls of Boer War by promoting a unifying moderate line against both the Limp jingoists and most ardent pro-Boers. Despite this, he was listed among the London Radicals, defending the interest of his voters from Poplar.

He was, all in all, the safest bet Spencer could make. As it was, Sydney Charles Buxton was both politically acceptable and the most experienced man for the job, having served as the former Under-Secretary of the Colonial Office in 1892-95.

A very plausible choice, and one that will provide an interesting contrast with Joe.

Little does he know that it is also likely to keep him safely away from icebergs.A very plausible choice, and one that will provide an interesting contrast with Joe.

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: