Technically, it's not starting a separatist movement, it's about making people affiliate with your nation so that when the Ottoman Empire collapses those people will look more to you than anyone else.Yeah, because clearly that's a better idea, instead of pissing off your smaller neighbors, you piss off the big one, and in a way they can link to you.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueYou might be surprised actually. The Ottomans viewed the school “wars” as a way of redirecting the various Christian groups at each other so they wouldn’t focus on the Ottomans themselves. Often times rewarding and punishing ethnic groups based on the geopolitical situation and who they liked at that moment. And it worked to a certain extent. The Greeks, Bulgarians, and Serbians spent a lot of resources on trying to beat each other in the cultural arena. It couldn’t last forever but it was at least partially effective. We’ll likely see some version of that ITTL as well.Yeah, because clearly that's a better idea, instead of pissing off your smaller neighbors, you piss off the big one, and in a way they can link to you.

Honestly looking at the situation on the ground I think the Greeks will likely get a lot of preferences and advantages ITTL as compared to OTL. Despite essentially blackmailing them for territory they kept their word, didn’t stab them in the back in their moment of weakness, and her Geopolitical backers are at least somewhat aligned with the ottomans. She’s not an immediate risk. Compared to the Bulgarians who are backed by the juggernaut that is the Russian Empire. Said juggernaut is an existential threat to their countries existence at this point. I think they’d rather every Christian in the Balkans speak Greek or Serbian at this point in time, and we’ll see those preferences in who is given the best territory to teach and preach in.

When we talk about ethnogenesis in Macedonia, we should always take into account local conditions, especially social. Economic relations, political loyalties, religious sentiments, all together formulated the different identities.

A nice book on the topic is "Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990". It describes the social conditions not in Macedonia in general, but Guvezna, nowadays Assiros, a village close to Thessaloniki. In Guvezna, a priest was first appointed in 1880. However, his liturgy was in classical greek, a language not understood by the majority of his flock. Soon afterwards, a greek teacher was appointed in Guvezna by the greek consulate in Thessaloniki. The teacher was paid by the greek merchants living around the marketplace of the town. Slavic-speaking sharecroppers from nearby chifliks were sending their kids in the greek school, as they had aspirations for their children to escape the sharecropper life and become teachers, merchants or artisans. For these occupations, greek was the lingua franca of the region.

What is interesting is that when the village was founded by a turkish bey who moved sharecroppers there (around the 1860s), the greek-speaking merchants that established their shops were actually hellenized Vlachs from Thessaly.

Eventually, four decades after the founding of the village a social stratification was well established. In the top of the food chain was the bey who owned the chiflik. In this particular village it was an absentee landowner who owned 1250 acres (5000 stremmata) of land. When he visited his estate during holidays, he lived in his mansion on top of the village. The second large landowner was again a turkish bey who owned a smaller chiflik and resided in a mansion as well. he operated an inn that was used mostly by muslim travellers. The overseers of the chifliks were also Turks and were treated as lords by the rest of the population.

Originally the christians of the region owned 1600 stremmata in total and gradually increased their land. Of them, the biggest landowner was a greek-speaker who had a southern Greek father and a slavic-speaker wife. He married a slavic-speaker woman. He owned 600 stremmata of land by the turn of the century that were cultivated by his children and six agricultural laborers.

Many upwardly mobile christians took up stockbreeding enterprises. They rented pastures from the two chiflik owners and they gradually used their profits to buy land and establish themselves as a rural middle class. This class was comprised of both greek and slavic speakers.

The migrant greek-speakers who established themselves in the village were most likely adventurous young males looking for economic opportunities. All the initial settlers married slavic women. They established themselves as grocers, bakers, merchants and artisans (coopers, saddle-makers, smiths) servicing the entire area. Most of their sons were married slavic women, while their daughters married affluent christians (greek and slavic speakers). The second generation of them took up "manufacturing" like cheese making, mills or services (inns, cafes).

The greek-speakers became a sort of local elite. The greek-speaking notables came to prominence and came to exercise a degree of authority over judicial, civil and religious affairs of the whole village. For example they were the ones who auctioned priviliged positions in the village such i.e. tax collectors, crop watchers, The greek-speakers became bilingual, speaking both greek and the local slavic language. As they prospered, the greek-speaking notables assumed patronage roles over the slavic-speaking sharecroppers, based on baptismal sponsorship and ritual kinship. These people became a force in the formation and consolidation of nationhood.

A nice book on the topic is "Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990". It describes the social conditions not in Macedonia in general, but Guvezna, nowadays Assiros, a village close to Thessaloniki. In Guvezna, a priest was first appointed in 1880. However, his liturgy was in classical greek, a language not understood by the majority of his flock. Soon afterwards, a greek teacher was appointed in Guvezna by the greek consulate in Thessaloniki. The teacher was paid by the greek merchants living around the marketplace of the town. Slavic-speaking sharecroppers from nearby chifliks were sending their kids in the greek school, as they had aspirations for their children to escape the sharecropper life and become teachers, merchants or artisans. For these occupations, greek was the lingua franca of the region.

What is interesting is that when the village was founded by a turkish bey who moved sharecroppers there (around the 1860s), the greek-speaking merchants that established their shops were actually hellenized Vlachs from Thessaly.

Eventually, four decades after the founding of the village a social stratification was well established. In the top of the food chain was the bey who owned the chiflik. In this particular village it was an absentee landowner who owned 1250 acres (5000 stremmata) of land. When he visited his estate during holidays, he lived in his mansion on top of the village. The second large landowner was again a turkish bey who owned a smaller chiflik and resided in a mansion as well. he operated an inn that was used mostly by muslim travellers. The overseers of the chifliks were also Turks and were treated as lords by the rest of the population.

Originally the christians of the region owned 1600 stremmata in total and gradually increased their land. Of them, the biggest landowner was a greek-speaker who had a southern Greek father and a slavic-speaker wife. He married a slavic-speaker woman. He owned 600 stremmata of land by the turn of the century that were cultivated by his children and six agricultural laborers.

Many upwardly mobile christians took up stockbreeding enterprises. They rented pastures from the two chiflik owners and they gradually used their profits to buy land and establish themselves as a rural middle class. This class was comprised of both greek and slavic speakers.

The migrant greek-speakers who established themselves in the village were most likely adventurous young males looking for economic opportunities. All the initial settlers married slavic women. They established themselves as grocers, bakers, merchants and artisans (coopers, saddle-makers, smiths) servicing the entire area. Most of their sons were married slavic women, while their daughters married affluent christians (greek and slavic speakers). The second generation of them took up "manufacturing" like cheese making, mills or services (inns, cafes).

The greek-speakers became a sort of local elite. The greek-speaking notables came to prominence and came to exercise a degree of authority over judicial, civil and religious affairs of the whole village. For example they were the ones who auctioned priviliged positions in the village such i.e. tax collectors, crop watchers, The greek-speakers became bilingual, speaking both greek and the local slavic language. As they prospered, the greek-speaking notables assumed patronage roles over the slavic-speaking sharecroppers, based on baptismal sponsorship and ritual kinship. These people became a force in the formation and consolidation of nationhood.

Is there a different between horses and oxen as draft animals in agriculture? And if so will a more economically powerful greece import/breed more draft horses? Aside from the economic development draft horses could be used in the army for pulling artillery and for logistics.

Horses are stronger and have more stamina, IIRC, which is why the invention of the Horse Collar was such a big thing.Is there a different between horses and oxen as draft animals in agriculture?

Its complicated, horses can do work faster but need more care so it came down to circumstance. Big fields are great for Oxen but small ones better for horses for example. Slow and steady is good for Oxen but anything else horses tend to win.Is there a different between horses and oxen as draft animals in agriculture? And if so will a more economically powerful greece import/breed more draft horses? Aside from the economic development draft horses could be used in the army for pulling artillery and for logistics.

Is there a different between horses and oxen as draft animals in agriculture? And if so will a more economically powerful greece import/breed more draft horses? Aside from the economic development draft horses could be used in the army for pulling artillery and for logistics.

I would like to add a big draft horse eats more than your regular greek ox. And it is more expensive to buy.Its complicated, horses can do work faster but need more care so it came down to circumstance. Big fields are great for Oxen but small ones better for horses for example. Slow and steady is good for Oxen but anything else horses tend to win.

Now Greeks had horses but compare a british Shire horse with a Pindus horse: Its like comparing an FT-17 with a Tiger.

The maintenance and husbandry of horses is also as a rule more demanding and finicky than that of cattle. Not only are cattle as ruminants more efficient and less picky of eaters than horses, (and more resilient against ailments such as colic), but they are less prone to crippling injuries that typically cannot be healed (particularly limb fractures).

So in other words oxen will be used to pull heavy loads and for plowing and small horses can be used for other things like threshing (did threshing boards in Greece have Flintstones like in Cyprus?)

Since this is a Greek Independence War timeline, I would like to share something I learned recently:

General Makriyannis in his memoirs describes the peraparations of the greek camp before the battle with Mustafa Resit Pasha who was besieging the Acropolis:

I knew that Makriyannis was famous for his skill with the tampouras and that he wrote at least one song- a lament. I didn't know that singing was part of the battle preparation.

Of course in TTL, Makriyannis is a veritable member of the National Party and supports Kanaris as the Prime Minister.

General Makriyannis in his memoirs describes the peraparations of the greek camp before the battle with Mustafa Resit Pasha who was besieging the Acropolis:

It seems the general was accompanying his men singing along with is famous tampouras, a lute-like instrument. It does seem that singing and sometimes dancing was often a part of their mental preparation for battle.We ate bread, we sang and celebrated before departing (for battle). We used to sing every time we were in battle.

I knew that Makriyannis was famous for his skill with the tampouras and that he wrote at least one song- a lament. I didn't know that singing was part of the battle preparation.

Of course in TTL, Makriyannis is a veritable member of the National Party and supports Kanaris as the Prime Minister.

Chapter 86: The New Order

Sorry for the extended delay between this part and the last. I actually had this chapter ready a couple weeks ago, but I wasn't really happy with the final product and essentially rewrote the entire chapter from scratch. My main issues were what to do with Bulgaria and Galicia. Originally, I intended on making Galicia a part of Russia, but later decided against that given the great backlash against Russia. Bulgaria was a bit more difficult to decide upon as Russia effectively controlled all the territory in question, barring the Mountains in the South, and the Bulgarians were active participants in the war (at least at the beginning). Ultimately, with Russian making great gains elsewhere and the building coalition against Russia, I don't think they would have been able to get everything they wanted here. Hopefully, what I settled upon in this chapter is reasonable for you all.

Chapter 86: The New Order

Scene from the Paris Peace Conference of 1857

Having become entirely convinced of their own wartime propaganda of Russian depravity and barbarity, the sudden arrival of a Russian peace overture at the end of October 1856 would catch the Palmerston Government completely off guard. Some, particularly British Prime Minister Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston suggested rejecting the Russian proposal outright as the “Rape of Galicia” had galvanized the whole of Europe against Russia. Austria was readying its Armies, whilst France was moving to support them and other countries such as the Netherlands, Bavaria, and Denmark were offering financial and material aid. The Kingdom of Hungary would signed a military alliance with Britain on the 4th of October, followed shortly thereafter by the United Kingdom Sweden-Norway on the 17th, with both promising to join the war by year’s end. Against such a coalition of Powers, Russia would be destroyed.

However, the Earl of Clarendon, Lord George Villiers and the Earl of Aberdeen, Lord George Gordon supported accepting Russia’s offer for peace. Britain was exhausted after two and a half years of war, while the Ottomans were a completely spent power incapable of providing even the meagerest resistance to the advancing Russians. Even with the added strength of Hungary and Sweden to their cause, and the potential intervention of Austria and France, the odds would only be balanced in theory as the Russians still had a million men under arms. Moreover, the Russians would be supported by an untold number of Armenian, Bulgarian, Cossack, Georgian, Greek, Moldavian, Serbian, and Wallachian auxiliaries. While Clarendon and Aberdeen did not doubt the skill and bravery of their own soldiers, nor their capacity to suffer and die for their country; the Russians would be equally prepared to fight and die in the defense of their Motherland.

The British people were also tired of this dreadful war, a war that had seen them make tremendous sacrifices for little apparent gain. Britain had suffered more than 60,000 casualties in two years of fighting, with 9,627 dying on the battlefield or from battlefield related injuries, whilst another 16,251 dying from illness and disease. 35,476 British soldiers would suffer from various injuries, many of whom were maimed losing arms or legs, hands and feet, eyes and ears. Others suffered from unseen injuries to the heart, the mind, and the soul, becoming little more than husks of their former selves.

Many Britons back home had also contributed to the war effort, donating money, clothing, or foodstuffs with little expectation of recompense or restitution at the end of the war. Taxes had been increased and war time bonds had been issued by the British Government to raise revenue for the war effort. By late 1856, many Britons simply had nothing left to give to their government. In their eyes, continuing the war would only worsen their suffering and their sacrifices, and for what? A small chance to dismantle the Russian Empire, to liberate Poland and Finland and the Muslims of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Their independence would not help the Yorkshire farmers or the London merchants, nor would their freedom appease the grieving mothers and wives whose menfolk had died to liberate them.

Finally, there was the matter of India. For the past eight months, the Indian Subcontinent had been embroiled in revolt by mutinous Sepoys and traitorous Nawabs. India was the Jewel of Britain’s burgeoning Empire – generating tens of millions in revenue via Company loan repayments and priceless trading commodities such as opium, tea, spice, silk, gold, and much, much more. If the reports of this past Summer were true, however, then the situation in the Subcontinent was becoming incredibly dire. The forces on the ground loyal to London and the East India Company (EIC) were outnumbered more than three to one and were in desperate need of reinforcements. If help did not arrive soon, then those few remaining Princely states still loyal to Britain might then rethink their loyalties to London and join with the rebels.

It was clear to Palmerston and his supporters that they could not pursue both the War against Russia and the Subjugation of the Indian Rebels at the same time. They had tried and they had failed. If they continued to pursue the war with Russia, they could likely succeed - with further costs in blood and treasure, but in the process, they would likely lose everything in India. Ultimately, Palmerston would agree to make peace with Russia with the hope that foreign pressure would limit Russian gains.

British Prime Minister - Lord Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Initial armistice talks would take place in the city of Berlin on the 15th of November. In attendance were the ambassadors from the War's primary belligerents; Baron Bloomfield (Britain), Count Brunnow (Russia), Yusuf Kamil Pasha (the Ottoman Empire), as well as representatives from Austria, Count Friedrich von Thun und Hohenstein, and France, Auguste de Tallenay. Before the proceeding officially began, Russian diplomat Count Philipp von Brunnow would offer a formal apology to the Austrian Government on behalf of the Russian government, laying the blame for the entire Galician Incident squarely at the feet of Prince Alexander Menshikov and the deceased Prince Alexander Chernyshyov.

Nesselrode hoped to avert war between Austria and Russia by scapegoating the dead Chernyshyov and the disgraced Menshikov, who had been swiftly cashiered and forced into an early retirement by Tsar Nicholas. The Russian Government also offered restitution for the wayward province of Galicia, even going so far as to suggest purchasing the state outright. Austrian pride compelled von Thun to reject the offer out of hand, however, he did promise to relay the offer to his superiors for further consideration. This would certainly not erase the irrevocable damage that had been inflicted, nor did it completely alleviate the threat of war between them, but it was a necessary step towards reconciliation between their two states. With that awkward exchange out of the way, the Armistice talks officially began.

These hearings would cover a wide range of topics from an official armistice date - set for the 24th of December – ceasing all hostilities between belligerent states, and a return of all prisoners taken on both sides over the course of the conflict. Britain would also agree to immediately vacate the Kamchatka Peninsula and end its naval blockades in the Baltic Sea – minor concessions given the fast approach of the Winter sea ice. In return, all Russian troops outside Varna, Shumen, and Trebizond would break their siege works and withdrawal 10 miles from the cities’ walls – movements that were already well underway in the Balkans. However, Britain would not vacate the Åland islands nor end its blockade of Russia’s Black Sea ports, which would remain in place until the start of the Armistice to incentivize Russian compliance. Similarly, the Russians kept their troops on the southern bank of the Danube and scattered across Eastern Anatolia -albeit scaled down considerably - in the event Britain attempted to back out of the peace talks or the Austrians invaded. Lastly, both sides would agree to attend a formal peace conference in three months-time.

However, the debate over the location of where exactly this Peace Conference would take place was perhaps the most contentious as neither side wished to have a hostile power host such an important event. For that reason, cities within the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and Great Britain were rejected almost immediately. Similarly, the Kingdom of Greece’s candidacy was opposed due to strong Ottoman opposition, whilst Sweden-Norway and Hungary were naturally blocked by Russia for their own apparent hostility to St. Petersburg. Prussia would be strongly considered by both parties initially, but ultimately rejected as the British felt it was too friendly to the Russians over the course of the war and had only condemned Russia’s illegal actions in Galicia once the rest of Europe had already done so. The cities of Spain and Portugal were considered too far, and the Italian and German states were considered too insignificant.

Ultimately, the choice came down to two cities: Vienna and Paris. With Austria still threatening war with Russia, however, the Russian delegation was hesitant to name Vienna as the site of the conference. Britain too did not fully trust the Austrians either, for while they were at odds with St. Petersburg now, their historical friendship and natural affinity might predispose them towards the Russians.[1] Moreover, Vienna as a city was on the decline in the years following the 1848 Revolutions. Many of the Hungarian elements of the city departed following the war and its separation from the rest of Germany only worsened this deterioration. The French diplomat Count Alexandre Colonna-Walewski would put it best, stating that Vienna was a city on the decline, a city of the past; whereas Paris was a city on the rise, a city of the future, with a booming population, great history, exquisite art, and a vibrant culture.

Great Britain and the Ottoman Governments had no qualms with selection of Paris given their good relations with the French during the war. The Austrian ambassador, von Thun also gave his support for Paris after some persuasion from his French counterpart. However, the Russian ambassador, Count Brunnow was more distrustful of Napoleon II than his counterparts, as the French Emperor had used the distraction of this war to sure up France’s position across the globe. The Egyptian succession crisis was quickly resolved in his favor, with the ascension of Ismail Pasha to the Khedivate’s throne. He had also expanded French holdings in Algiers, whilst Algerian and Berber ghazis were ferried to the Balkans and Anatolia to fight against Russia on the Ottoman Porte’s behalf. France had similarly expanded its influence into Southeast Asia, establishing colonies in the South Pacific and forging commercial ties with the countries of Indochina.

Moreover, French material support for the Anglo-Ottoman alliance during the war had resulted in thousands of additional Russian casualties and needlessly extended the war for many weeks and months. Finally, they had applied significant financial and diplomatic pressure on St. Petersburg during the latter stages of the war, refusing to provide loans for Russia and convinced several of its allies to do the same. However, France had not taken up arms against Russia directly, nor had it imposed extreme demands upon St. Petersburg even after the Galician Incident. There was also a degree of flexibility that could be found in the French Government towards Russia as opposed to the British or Turks. After careful consideration, Count Brunnow would accept Paris’ candidacy for the ensuing Peace Conference, bringing the armistice talks to an end.

With the Armistice finally agreed to, the cursory skirmishing and raiding that had characterized the Balkan and Anatolian front lines over the last few months of the war gradually gave way. When the Armistice Day finally arrived, many Russian and British soldiers cheered for their trials and tribulations were now at an end. Former enemies would even congregate together, trading souvenirs, sharing drinks, and singing festive songs for their war was over and their reasons to fight were gone. Word would soon arrive in Tehran of Russia’s move towards peace, convincing the Qajari Government to dispatch their own emissaries to the British. Although they considered the Persians to be vile opportunists that had taken advantage of Britain’s momentary weakness, London had more pressing matters to attend to in India and quickly acquiesced to the Qajari request for peace. Nearly two months later in mid-February 1857, the representatives of Great Britain, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, the Qajari Empire, Austria, Hungary, Prussia, Sweden-Norway and Greece arrived in Paris to finalize the terms of the Peace between them.[2]

Although the Congress would not officially start until the 10th of February, talks had continued throughout the Winter, resolving many of the lesser issues at hand. Britain’s blockade of Russia’s Black Sea ports was ended on the 1st of January and both sides agreed to cease all financial and material support for partisans within the other’s countries. Most importantly, free navigation of the Danube River and Turkish Straits for commercial vessels of all nations were agreed to by the Congress’ participants. By the time the Conference’s attendees arrived in early February, the only issues remaining were those regarding territorial claims and suzerainty.

As the Great Eurasian War had technically been started by the Ottomans on behalf of the Caucasian Muslims, this debate would begin with the North Caucasus. Unfortunately, events in the region had conspired against the Circassian Confederacy and the Caucasian Imamate as both were prevented from attending the Paris Peace Conference. This was by design as the Russian Government had vehemently opposed their attendance. In their eyes, the Caucasian Muslims were uncivilized mountaineers and tribesmen living on sovereign Russian territory as agreed to under the 1829 Treaty of Adrianople and had no grounds for representation in Paris. The other Powers of Europe had little interest in the plight of the Caucasians, either out of disdain for the Muslims or a general disinterest in the region. Only Britain and the Ottomans showed any significant interest in their inclusion, but they were dealt an incredibly bad hand by late 1856.

With the fall of Fort Navaginsky earlier in the Spring, the Circassian Confederacy and Caucasian Imamate were effectively surrounded on all sides by the Russians. Things would only get worse from there as the Caucasian Imamate’s leader, Imam Shamil and many of his chief lieutenants were captured by the Russians during a raid in late October. The ensuing power vacuum would result in defeat after defeat for the already overwhelmed and leaderless Imamate. Although a few Chechens and Dagestanis would continue to resist the Russians for months and years to come, the loss of Shamil effectively decapitated the Imamate’s leadership, depriving it of a charismatic figure for his people to rally around and one that foreign nations could recognize and support.

The situation was equally dire for the Circassian Confederacy which had fractured in recent months. Several of its tribes advocated submission to the Russians in order to safeguard what was left of their peoples and homeland, while others continued to push for war against Russia and refused any call for peace. Such a split became irrevocable for the Circassian resistance as those that wished for peace broke with their brothers and surrendered wholesale once news of the armistice between Britain, the Ottomans, and Russia arrived on the 11th of January. Those that remained opposed to the Russians would continue to fight, but their fate was effectively sealed by London’s decision to make peace with St. Petersburg.

Unable to reach the Ciscaucasian Muslims, nor decide upon a proper authority in the region, the Russians were ultimately able to prevent Britain and the Ottomans from seating any representatives from these troubled lands at the Paris Peace Conference. Without their direct involvement, the session regarding their fate would move swiftly, as the British quickly traded their support for the North Caucasus Muslims in return for Russian concessions in Eastern Anatolia. Namely, the Russians would abandon their claims to the port of Trabzon. So long as Trabzon remained outside of Russian hands, Britain’s economic interests in Anatolia could be safeguarded. The Ottomans would be more reluctant to abandon their nominal subjects to Russian indignities, but without British support there was little they could do. Ultimately, they would surrender their claims of suzerainty over the Caucasus Muslims in return for “guarantees of their rights to practice their faith and live according to their own customs”. Although it was magnanimous of the Russians to agree to this concession, in truth this was little more than lip service by the Russians, as they would promptly violate the terms of this agreement before the ink had even dried.[3]

Circassians Surrendering to the Russians

With the North Caucasus largely settled, the discussion would turn southward to Eastern Anatolia/Western Armenia where Russia’s conquests were the most extensive. Utterly smashing the Ottoman frontier, the Russian Armies of General Muravyov had captured the fortress city of Erzurum and marched as far West as the Zara, and from the Black Sea coast to the shores of Lake Van. Outside of the port of Trabzon, however, Russia’s interests in Eastern Anatolia were rather mercurial given the poorness of the region and overly hostile demographics of its people. Their subsequent decision to abandon their claims to Trabzon came as a great surprise, but this was likely done out of pragmatism, trading Trabzon for peace in the Caucasus. So long as the Caucasus Muslims received foreign support, Russia could never truly pacify the region. Moreover, they did not hold Trabzon at War’s end, meaning any attempt to claim it would have required concessions elsewhere, which would have been steep given the great value both the British and the Ottomans held for the port city. Ultimately, Nesselrode and Orlov would agree to end their pursuit of Trabzon - for now.

Instead, the Russian delegation would work towards consolidating their hold of the Armenian highland which Russia had occupied in its entirety during this war. By owning this region, Russia would strengthen their frontier with the Ottomans immeasurably, whilst denying the Turks many of the hills and valleys that had been their greatest defensive works in this last conflict. Moreover, it would leave the Ottoman provinces in Central Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Levant dangerously exposed to Russian attack, giving St. Petersburg tremendous influence over Ottoman policy. Finally, it would bring most of the Armenian peoples under Russian protection, leaving only a few far-flung communities outside its borders.

These claims to the Armenian Highlands would not go unchallenged, however, as the Turks, the British, and the French all opposed Russia’s claims to the region. The Ottomans naturally opposed these demands, as accepting them would leave the Anatolian Plateau – the Ottoman heartland at great risk. It would also see Turkish lands and Turkish peoples fall under foreign occupation, a situation that would destroy the Porte’s legitimacy in the eyes of their people. The British opposed Russian expansion into Eastern Anatolia as doing so would render Russia’s earlier abandonment of Trabzon moot. With the Eastern Anatolian interior in Russian hands, they would control almost all the land routes to and from Trabzon – but for the western road, effectively making Trabzon a Russian port in all but name. Finally, the French opposed Russian expansion into the Armenian Highlands as it would leave Syria and Palestine under serious threat, potentially jeopardizing France’s influence in the region. Yet, even in the face of this staunch resistance, Russia could have forced the issue if they so desired, but in doing so, they would have had to forsake making gains elsewhere.

Although they held some interest in the lands of Eastern Anatolia, this paled in comparison to the value they held for the Balkans. Eventually, the Russian delegation would agree to limit their gains in Eastern Anatolia to the border Sanjaks of Alashkerd, Ardahan, Ardanuç, Beyazit, Hanak, Lazistan, Mahjil, Oltu, Posof, the eastern half of the Erzurum Sanjak, and a small sliver of the Trabzon Sanjak.[4] Despite this marked reduction from their earlier demands, this still represented a massive loss for the Ottoman Empire, one which the Ottoman delegation was hesitant to accept. Yet, given the difficult battle spent reducing Russia’s demands even this much, the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha reluctantly agreed to sign away many of his nation’s eastern provinces. The delineation of the new border between the Ottomans and Russians in Anatolia would thus run westward from the frontier with the Qajari Empire near Mount Tendürük, across the hilltops of the Agri Par west of Agri, and through the Erzurum valley just west of Erzurum. From there, the border would travel north to the Pontic mountains and proceed down the Ophius river to the town of Ofis on the Pontic coast.

The decision by the Western Powers to accept Russian gains in the East was likely done with the express purpose of limiting their gains in the Balkans as much as possible, given the greater wealth and importance of the region. Unlike Anatolia, St. Petersburg’s objectives for the Balkans were quite clear; above all else they desired the city of Constantinople for themselves. However, failing this, they wished to drive the Turks from the Danube, thus nullifying their defenses there and securing a future invasion route. Clarendon recognized this and together with his French and Ottoman Allies, he sought to form a cohesive block against the Russians, forcing them to give up their claims and end their aspirations in the Balkans. To their credit, Nesselrode and Orlov had expected this opposition and would refrain from claiming any territory in the Balkans for Russia directly. Instead, they would look towards expanding Russia’s influence across the Balkans, by establishing a series of satellite states in the region, beginning with the Danubian Principalities.

In an impassioned speech, Prince Alexey Orlov would argue that the Ottoman Government had voided their rights to suzerainty over the Danubian Principalities with its illegal and unprovoked invasion of Wallachia and Moldavia in early May 1854. Through its actions, several thousand innocents had been slain, while an untold number were left destitute by Turkish raids. This was not the behavior of a benevolent overlord, but a vindictive aggressor. In contrast, the benevolent Russian Tsardom had defended its brothers in faith and beaten back their attackers in self-defense. Therefore, the Russian Empire should be considered the rightful protector and benefactor of the Danubian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, not the Ottoman Turks.

Russian Ambassador to France, Count Alexey Fyodorovich Orlov

Despite the dubious authenticity of Orlov’s words (more Wallachians and Moldavians had actually died fighting for the Russians outside Silistra than in the entire Ottoman invasion), the Allied contingent to the Paris Peace Conference would concede this demand almost immediately. Even the Ottoman delegation recognized the Principalities were a lost cause and only offered a token resistance to the measure, if only to preserve their Government’s honor. Relatively speaking, it was a minor concession as the Porte’s authority over the two principalities had been thoroughly eroded in the years preceding the war; their inability to defeat Russia during this conflict only solidified this fact. Nevertheless, it was still a decisive development as the two Principalities were now nominally independent after nearly 400 years of Ottoman overlordship.[5]

In truth, however, the two states would be little more than Russian protectorates, effectively trading an Ottoman suzerain for a Russian one. The loss of Wallachia and Moldavia to Russian rule was made easier for the Western Powers thanks to the protections given to commercial vessels on the River. Nevertheless, for countries such as Hungary and Austria, the “independence of Wallachia and Moldavia was an unwelcome development. With Wallachia and Moldavia secured, Russia turned its attention westward, across the Danube to the Principality of Serbia.

Like the two Danubian Principalities to the East, Ottoman control over Serbia had gradually declined over the last 50 years following the outbreak of the Serbian Revolution and the establishment of the Principality of Serbia in 1815. In more recent years, the Prince of Serbia, Aleksandar Karađorđević had signed a treaty with the Porte, further reducing Ottoman influence within the country, thereby stripping their garrisons to the bare minimum. Although the Principality had remained neutral throughout the conflict, many of its citizens had journeyed abroad to fight alongside the Russians in their war against the Turks. Similarly, many Serbs within Ottoman territory would also rebel against the Sublime Porte. All told, nearly 31,000 Serbians would participate in the war, either as auxiliaries in the Russian Army or as brigands raiding Ottoman patrols.

Despite this factor, Allied resistance to Serbian independence would be far stouter than it had been with Wallachia and Moldavia. Unlike the previous matter, Russia did not have a physical presence in Serbia, whilst the Ottomans still did, albeit to a limited extent. There was also the fear that an independent Serbia would encourage Serbian nationalists in both the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary to rebel against their overlords and join their lands with the Serbian state, a fact that greatly concerned Buda. Moreover, the reigning Prince of Serbia, Aleksandar Karađorđević was generally viewed as a Russophile by the British and French governments, one who would align his state with St. Petersburg if given the chance. Such a development would extend Russian influence into the Western Balkans and onto the Southern borders of Austria and Hungary, something which neither state could accept.

However, according to reports from Belgrade, Prince Aleksandar was increasingly unpopular with members of the Serbian government over his increasing nepotism and flagrant disregard for the Legislature. Although he remained relatively popular with some elements of the Serbian people, his grip on power was still quite tenuous thanks in no small part to the machinations of his predecessor, Prince Milos Obrenovic. Prince Milos had been working tirelessly to reclaim his and his son Mihailo’s throne, using his connections and his vast wealth to spur unrest within Serbia against Prince Aleksandar. To further his own interests, Prince Milos and his son had journeyed to Vienna where they stayed for several years, before traveling to Switzerland in 1848, and then Paris in 1851 where he had spent the last few years petitioning the French Government for support.

Following up on this lead, Lord Clarendon and his French counterpart, Edouard de Lhuys would meet in secret with Prince Milos during a brief recess in the Conference. Coming to terms with the exiled Serbian magnate, they reached a tentative agreement whereby the British and French governments would support a coup in Prince Milos’ favor in return for his alignment with the Western Powers of Europe, to which Prince Milos readily agreed. Clarendon and de Lhuys would then meet with the representatives of Austria and Hungary, gaining their support for Milos’ coup in return for promises to renounce Serbian claims on Hungarian or Austrian territory. With a secret arrangement established between Britain, France, Austria, and Hungary to support the deposition of Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević and the return of Milos Obrenovic, they eventually agreed to Russia’s demand for an independent Serbia. However, the process would be a gradual one, with the Ottomans slowly transitioning power to the Serbians over the course of the next three years, before finally gaining its full independence in January of 1860, time enough for their plot to take effect.

Prince Milos Obrenovic of Serbia

The Plenum’s attention would then turn to the tiny Principality of Montenegro located southwest of Serbia. Ottoman control over the region had always been tenuous, owing to the mountainous terrain and warlike nature of its people – the poorness of the region did little to help matters. Recently, however, what little sway the Ottomans held over the region had been completely destroyed when a band of Montenegrins massacred an Ottoman regiment sent to police the region, near the town of Kolasin. Under normal circumstances, such an event would have warranted a major retaliation, but with the war with Russia raging to the East and revolts all across the Balkans, the Porte had few resources to divert to little, insignificant Montenegro. Effectively, the decision to now give Montenegro independence was merely a recognition of the reality that Montenegro was independent of Kostantîniyye’s control and had been for nearly two hundred years.

The last major bone of contention in the Balkans were the lands of Bulgaria. Numerous Bulgarians had risen in revolt against the Ottomans, with nearly 47,000 volunteers joining the Russians in the early weeks of the war. Sadly, many of these partisans were ill equipped, and the Russians proved unable to support them given their early setbacks, leading to their brutal repression by the Ottoman authorities. Overall, some 18,000 Bulgarian men, women, and children would be slain in 1854 alone, many of whom having little to do with the revolt against the Porte, with many more falling in the years that followed. Such injustice could not stand in the eyes of St. Petersburg and they called on their counterparts to release Bulgaria from Turkish oppression. However, this was a step too far for the Western Powers.

When combined with the independence of Serbia, Wallachia, and Moldavia; the liberation of Bulgaria would effectively make the Danube a Russian river in all but name. Such an outcome was simply unacceptable to Buda and Vienna whose economies were reliant upon free navigation of the Danube River for trade and commerce. There were also considerable concerns over the extent of an independent Bulgaria, with the Russian delegation proposing a Bulgarian state extending from the Danube to the Balkan Mountains and the Black Sea to the border with Serbia. Such a state would cause irrevocable damage to the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, leaving its European territories incredibly vulnerable to invasion and insurrection. Most of all it would leave the Turkish Straits dangerously exposed to the Russians, something which the British, French, Austrians and Ottomans vehemently opposed.

Tensions over Bulgarian independence rose quickly to the point where Lord Clarendon and Mehmed Pasha threatened to walk out of the Peace Conference and continue the war no matter the cost, forcing Nesselrode and Orlov to walk back their demands considerably. Perhaps if Russia had made peace in the Summer when their enemies were at their weakest, then they may have had a better chance at winning Bulgaria. Instead, in the face of a united opposition, they would abandon their ambitions of a Bulgarian satellite in favor of the demilitarization of Dobruja, the rights of the Bulgarians guaranteed by the Ottoman Government, and the codification of Russia’s role as the protector and benefactor of the Ottoman Christians. With the fate of Bulgaria settled – for now, there remained one final measure in the Balkans, that of Greece’s treaties with Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire.

Signed in the Spring of 1855, the Treaty of Corfu and the Treaty of Constantinople would have the Kingdom of Greece annex the Ionian Islands and the Dodecanese Islands respectively. A separate clause in the latter treaty would also see Thessaly and Epirus ceded to Greece by the Ottoman Empire in return for its continued neutrality in the war, which the Hellenes had – mostly - abided by. However, what should have been a simple matter of acknowledging the two earlier treaties and confirming Greece’s new borders, quickly became complicated as the British delegation under Lord Clarendon called for an abrupt recess in the congress before quietly calling aside his Greek counterparts, Konstantinos Kolokotronis and Nikolaos Kanaris. What was said exactly during this private exchange is unknown, but the subtext of their exchange is abundantly clear; London had known about Greece’s continued duplicity throughout the War – both smuggling and sedition - and was clearly irritated by it.

Greece’s illicit succor had buttressed the flagging Russian cause during the latter stages of the war, contributing in part to the Russian victory and increasing British casualties by an untold margin. Although it cannot be said that Greek support for the Russians resulted in a Anglo-Ottoman defeat in the war, it was seen as highly insulting to the British Government. London had gone to great lengths to convince the Greeks against going war with the Turks, instead offering them numerous bribes and concessions in the hope their honor would hold them to their agreement; they were wrong. This is unfair to say the least as the Greek Government did abide by the terms of the Palmerston-Kolokotronis Treaty, if not in spirit, then at least in letter. More than that though, it would set a dangerous precendant that the Government of a people is responsible for all their people's actions when beyond their borders.

While Britain promised not to take any overt actions against the Greek Government out of respect for their mutual friendship and their desire to maintain a united front against Russia, they reiterated that any future sedition within the Ottoman Empire would be interpreted as an act of aggression by the Greeks, thereby nullifying Britain’s defensive pact with Greece. This is not to say that Britain would attack Greece, merely that they would not aid Greece if the Ottomans retaliated against them. Beyond this thinly veiled threat, the British Government would also request that they receive a 25% share in the Corinth Canal's revenue in return for their continued support of the canal’s construction. Finally, Clarendon asked that they pay a minor indemnity to the Ottoman Government for their new provinces, with a sum being established between the two at a later date. The British would chose to forgo an indemnity for the Ionian Islands, instead negotiating that their lease on the Port of Corfu be extended another 10 years, later negotiated down to 5 (now ending in 1870).

Reluctantly, Konstantinos Kolokotronis accepted these terms on behalf of the Greek Government, viewing Britain's tacit support for Greece’s expansion into Thessaly and Epirus as more important than a few, relatively minor economic concessions to London and their Turkish lackies. However, this exchange would prompt a marked cooling off period in British-Greek relations for the next several years. Nevertheless, the British delegation quickly returned to the Conference Chamber and gave their consent to Greece’s annexation of Thessaly and Epirus, quickly followed by Russia, France, and all the other delegates in attendance. With the new borders in the Balkans established, the discussion moved northward to Galicia-Lodomeria.

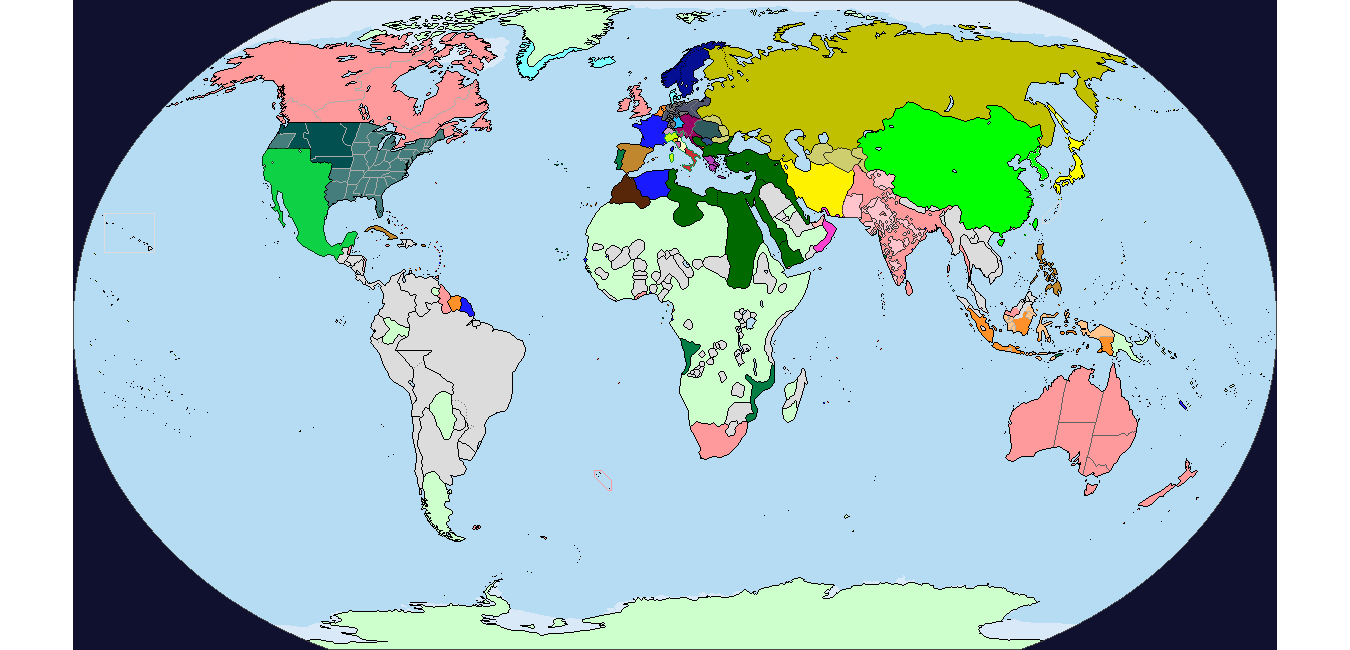

The Kingdom of Greece's borders post Paris Peace Conference

Prior to the recent debacle over Russia’s illegal activities in the region, Galicia had been a de jure part of the rump Austrian Empire. In recent months, however, it was abundantly clear for all to see that Vienna’s authority in the province had waned considerably since 1848 as Polish rebels and poor infrastructure limited their ability to govern the far-flung country. Russia had a sizeable role in this as well, as they had moved their own officials into positions of power within Galicia, assuming roles previously held by their Austrian counterparts – tax collector being one of the most prominent. Despite their recent efforts to reinforce their position in Galicia, the Austrian Government simply had no power projection in the province by 1857 and could not realistically govern it as this recent scandal made apparent. For the good of all involved, it would have to be sundered from the Austrian crown and either made independent or subjected to Russia.

The former option was deemed unacceptable by Russia and Prussia as a fully independent Polish state would only embolden their own Polish subjects to rebel. This was hardly an issue for Britain and France as they both supported an independent Poland, but the Russians - with considerable backing from the Prussians, would not budge on the issue. The Second option of Russian annexation was then considered with the earlier offer to purchase Galicia now given more credence. However, Austria was against the measure as doing so would effectively reward Russia for its infidelity. To mollify the Austrians and satiate the Russians, Galicia-Lodomeria would be established as a subject state of Russia, akin to the Danubian Principalities and under the rule of a Hapsburg Prince.

This new country would be akin to the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, with the state being de jure independent, but financially, diplomatically, and militarily dependent upon Russia, making it a Russian province in all but name. The now detached Duchy of Bukovina would then be sold to the Principality of Moldavia for 2 million Pounds Sterling, paid for by their overlord Russia. St. Petersburg would also pay Vienna a grand total of 24 million Pounds Sterling for the province of Galicia-Lodomeria, effectively repaying Austria their missing funds for 1856 and much, much more.[6] However, for cash strapped Russia, this amount was far more than it could afford at present. To pay for this sum and to further appease the angered Austrians, Russia would be forced to make sales of their own, namely its lone colony in the New World, Alaska.

A Map of Russian Alaska (circa 1854)

Located on the far side of the Bering Strait, Alaska had always been a backwater, even for Russia. The colony had received little interest from St. Petersburg over the years and was only inhabited by a few thousand native Inuits and several hundred Russian fishermen, hunters and fur traders – the last of which had started departing Alaska after the exhaustion of the local sea otter population. Nevertheless, it was a vast territory spanning nearly 1.7 million square kilometers with countless forests and untapped natural resources whatever those resources happened to be. It was also completely indefensible for Russia – as made abundantly clear by this recent war when the British swiftly occupied the colony in a matter of weeks. Given the great distance and geographic boundaries separating it from the Russian heartland, there was no feasible way for St. Petersburg to exercise its authority over the colony, nor could it properly defend it. With the value of the province now on the decline with the decline of the sea otter population and Russia in desperate need of money, the decision was ultimately reached to sell the colony to the highest bidder.

That bidder would be Britain for a grand total of 7 million Pounds Sterling, however, Britain’s interest in the colony was rather low despite the high price paid for it. Apart from a few extra ports, fishing rights, and timber, the colony would add very little to the British Empire. Its size was certainly nice as it would solidify Britain’s position on the Pacific, but most of the territory was frozen wasteland that was largely uninhabited and poorly developed. Nevertheless, Britain would be compelled to buy the colony from Russia as “recompense” for Russian gains elsewhere - the fact that the money used to buy Alaska would ultimately go to Austria, rather than Russia also helped the British people stomach the purchase.

When this was still not enough to cover the costs of Galicia, the Russians would also be compelled to sell the Åland Islands to the Kingdom of Sweden-Norway for the sum of 2.5 Million Pounds Sterling. The sale of the Åland Archipelago was a modest loss for the Russian Empire, as St. Petersburg had invested much into the islands over the last 48 years with the construction of Bomarsund Fortress and its outlying redoubts. However, the islands were overwhelmingly Swedish demographically, they were relatively poor economically, and generally indefensible against a dominant sea power like Britain – a fact that had been humiliatingly exposed in 1855. Thus, selling the islands to a middling power like Sweden was of little consequence in the grand scheme of things as Sweden-Norway was nothing compared to the might of Russia. To sweeten the deal in St. Petersburg’s favor, Nesselrode would also force the Swedish Foreign Minister, Gustaf Stierneld into demilitarizing the islands and a renouncing any further Swedish claims on Russian territory.

The final area of major territorial changes would be Central Asia, particularly the region between British India, the Qajari Empire, and the Russian Empire. The Khanates, Emirates, and nomadic tribes that inhabited this land had largely aligned themselves with the British against the Russians during the war as they opposed Russian expansion into their lands. However, given the greater importance of the Baltic, Balkan, and Anatolian theaters of war, little attention had been given to Central Asia during the first two years of the conflict, forcing the overwhelmed local garrisons to fend off the rebel Turkmen on their own. Only in mid 1856 would St. Petersburg begin shifting forces Eastward to subdue Turkestan and by the end of the year, most of the Kazakh lands had been pacified. However, the Emirate of Bukhara, the Khivan Khanate, and the Kokand Khanate were still free of Russian occupation by the start of the Paris Peace Conference.

Although Britain had little capability of supporting the Central Asian Turkmen, Clarendon did not wish to completely abandon them either as the United Kingdom had established considerable financial and diplomatic relations with the tribes in the region. Moreover, they wished to preserve a series of buffer states between British India and the Russian Empire, a role which these states had previously occupied before the war. As British opposition was stiffest here, whilst Russian interest in the region was relatively low; the two would eventually reach a compromise restoring the status quo antebellum in the region. Whilst this did see the lands of the Kazakhs reincorporated into the Russian Empire and formally recognized by the other Powers as sovereign Russian territory, it would also see the Khanates of Kokand and Khiva, and the Emirate of Bukhara retain their nominal independence, albeit as Russian tributaries. Nevertheless, this did fulfill Britain’s goals of maintaining a buffer between British India and the Russian Empire, while also preserving their ability to trade with the Central Asian states.

Moving southward, Persia’s invasion of Afghanistan in late 1855 would expand the conflict to Afghanistan and Northern India, although the former was quickly conquered and pacified by the Qajaris. Britain had attempted to ready a punitive expedition againt the upstart Persians, but the revolt of the Sepoys and Nawabs of India in early 1856 would derail Britain’s plans. Despite this setback, the indomitable British Royal Navy rained destruction upon the Persian Gulf ports and caused immeasurable damage to the Qajari economy with their blockades and interdictions forcing the Qajaris to the table on relatively generous terms. The deal reached by British and Qajari Governments would effectively partition the Emirate of Afghanistan between them, with the Hindu Kush mountain range serving as the boundary of their realms.[7]

Although Britain had gone to war with the Qajaris to maintain the independence of Afghanistan, London valued the strategic nature of Afghanistan more than the Emirate itself, as its territory spanned many of the main passes into and out of Northwestern India. With these routes securd under British control, the importance of the Emirate diminished substantially, hence the concession to the British by the Qajaris. The two states would also agree to split the Khanate of Kalat, located to the south of Afghanistan, with the Qajari Empire receiving the Ras Koh and Chagai Hills, while the remaining rump state would fall under British suzerainty thus securing India’s Western approaches as well. Overall, the arrangement favored Tehran more than it did London, but given the ongoing revolt in Bengal and their previous failure in conquering Afghanistan in 1839, the deal was more than enough to satisfy London.

With all outstanding border changes resolved and confirmed by the Conference’s participants, the Conference proceeded to the last major topic of discussion, that of the Turkish Straits. Debate over free passage of trading ships through the straits had been quickly resolved before the Conference, with commercial vessels of all countries being permitted free access through the Straits. However, the issue of warships would be much more contested and extended into the Congress for debate. Russia desperately wanted to secure the Straits against a hostile power, thus safeguarding their soft southern underbelly against foreign adversaries. They also wanted to send their own warships through the Straits as a means of exerting its influence in the Mediterranean.

Britain abhorred the thought, as did the French and Austrians who came to see a Russian presence in the Mediterranean as a threat to their own interests on the Mediterranean. After much debate, and several threats of renewed war, costs be damned; both sides would reach a compromise. The Ottoman Porte would be forced to refuse all foreign warships passage through the Dardanelles, whilst Russian warships would be similarly banned from passing through the Bosporus Straits. This arrangement satisfied neither party, but of the two, Russia came out better as they had effectively made the Black Sea a Russian lake in the process. The last days of debate would go rather quickly and uneventfully resolving the remaining issues one by one, until the 15th of March when the Conference’s participants gathered together for one last meeting, to sign the Treaty of Paris.

The Delegations sign the Treaty of Paris (1857)

Ultimately, the Great Eurasian War, or War of Turkish Aggression as it is known in Russia, would go down as a great victory for Russian Emperor Tsar Nicholas. He had gained great territory in Anatolia and he had established several friendly satellites across the Balkans. He had also secured free shipping through the Straits and a denial of foreign warships from the Black Sea. Yet it was not as great as it could have been thanks to scandals and poor diplomacy in the last year of the war. Moreover, Russia had suffered over a half million casualties, its economy was crushed by blockades and embargoes, and it minorities in the Caucasus and Crimea had revolted, despoiling the countryside. In the end, Russia’s ascendancy, whilst slowed greatly by the war, would ultimately rebound in short order and continue to grow, faster than before thanks to their great gains in Anatolia, the Balkans and Galicia.

For the Ottomans it was a solemn affair as their nation had suffered the worst out of all the war’s participants. Their armies were shattered, suffering well over a quarter million casualties. Their territories in the Balkans and Anatolia had been despoiled by war and revolt. Their economy was on the brink of ruin, driven deeply into debt by wartime expenditures. More annoyingly, they had been the only major belligerent in the war to lose territory (ignoring Russia's selling of Alaska and Aland), whilst their primary ally Great Britain had actually gained territory. They had also lost any remaining semblance of control in the Danubian Principalities, Serbia, and Montenegro, which only furthered unrest in their Balkan provinces. Their “victories” in the Paris Peace Conference had been relatively minor as well, having only secured the welfare of the Ciscaucasian Muslims - a provision that was quickly ignored by Russia in the following months, and the retention of Bulgaria, Erzincan, and Trabzon - regions thoroughly devastated by the war. Overall, there would be much for the Sublime Porte to contend with in the years ahead as they struggled to deal with their newfound anger and shame.

For their part, the British would make out relatively well as they had made moderate gains in the war with their purchase of Alaska and their annexations in Afghanistan and Baluchistan. Their economy whilst exhausted from war, was largely intact and would recover in a few years’ time. Internally, the British Government would review their performance in the War poorly, resulting in a series of military reforms in the years ahead in the hopes of addressing many of their military’s shortcomings. Publicly, Westminster would lay the blame for their defeat at the feet of the Indian Rebels for distracting them and drawing away their resources. The soldiers and their families would be far harsher on their Government, however, blaming the Palmerston Government for their poor handling and poor preparations for the war, resulting in the Tories being ousted from Power in the 1857 elections. However, the Great Eurasian War was not over yet, not for Britain anyway as there remained one last theater of war for it to contend with.

Next Time: The Devil's Wind

[1] The British were quite guarded towards the Austrians in OTL and resisted efforts to name Vienna as the Peace Conference’s locale.

[2] Also in attendance were various observers from Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, Serbia, Montenegro, Wallachia and Moldavia.

[3] Although Russia is formally agreeing to protect the rights of its Muslim populations, there are no enforcement mechanisms on this, nor are there any states willing to intervene on their behalf. As such, the fate of the Circassians will generally be the same. However, the earlier surrender by several tribes and clans (brought about by the Allied defeat against Russia) should save lives and preserve more of their communities relative to OTL.

[4] This essentially represents Russia’s claims in the OTL Treaty of San Stefano plus a little more.

[5] Although Wallachia was technically a tributary of the Ottoman Empire beginning in 1417, it was generally sporadic as the Voivodes usually resisted paying tribute to the Ottomans, only to be summarily invaded and deposed by Ottoman backed rival claimants. After Vlad the Impaler’s death in 1476, Ottoman suzerainty over Wallachia was formalized and would remain largely intact for the next four hundred years, apart from the reign of Michael the Brave in the late 16th Century. Similarly, Moldavia briefly became an Ottoman tributary in the 1450’s, but this would largely stop during the reign of Stephen the Great. However, by the end of Stephen’s reign, he was forced to accept Ottoman suzerainty once more, a state of affairs that would continue intermittently until 1876 in OTL.

[6] I’m using the Gadsen Purchase as a reference for this pricing as the size of the territories in question are roughly the same at around 77,000 km^2 for the Gadsen Purchase and 78,500 KM^2 for Galicia-Lodomeria. The timing of this exchange is also very close to the OTL Purchase which happened in 1853 so the valuations should be relatively similar. However, I’d wager that Galicia and Lodomeria would cost far more than the desert that America purchased from Mexico. Firstly, Austria is not a defeated state that can be pushed around like Mexico post Mexican-American War, although it is believed that the US vastly overpaid for the region in question. Secondly, Austria has most of Europe supporting them in this matter so Russia can’t shortchange Vienna here. Finally, there are several million people living in Galicia and Lodomeria, albeit most are poor peasants and farmers, whereas the area of the Gadsen Purchase was largely inhabited by a few thousand people.

[7] Roughly corresponding to the territory Britain would seize from Afghanistan in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

Chapter 86: The New Order

Scene from the Paris Peace Conference of 1857

Having become entirely convinced of their own wartime propaganda of Russian depravity and barbarity, the sudden arrival of a Russian peace overture at the end of October 1856 would catch the Palmerston Government completely off guard. Some, particularly British Prime Minister Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston suggested rejecting the Russian proposal outright as the “Rape of Galicia” had galvanized the whole of Europe against Russia. Austria was readying its Armies, whilst France was moving to support them and other countries such as the Netherlands, Bavaria, and Denmark were offering financial and material aid. The Kingdom of Hungary would signed a military alliance with Britain on the 4th of October, followed shortly thereafter by the United Kingdom Sweden-Norway on the 17th, with both promising to join the war by year’s end. Against such a coalition of Powers, Russia would be destroyed.

However, the Earl of Clarendon, Lord George Villiers and the Earl of Aberdeen, Lord George Gordon supported accepting Russia’s offer for peace. Britain was exhausted after two and a half years of war, while the Ottomans were a completely spent power incapable of providing even the meagerest resistance to the advancing Russians. Even with the added strength of Hungary and Sweden to their cause, and the potential intervention of Austria and France, the odds would only be balanced in theory as the Russians still had a million men under arms. Moreover, the Russians would be supported by an untold number of Armenian, Bulgarian, Cossack, Georgian, Greek, Moldavian, Serbian, and Wallachian auxiliaries. While Clarendon and Aberdeen did not doubt the skill and bravery of their own soldiers, nor their capacity to suffer and die for their country; the Russians would be equally prepared to fight and die in the defense of their Motherland.

The British people were also tired of this dreadful war, a war that had seen them make tremendous sacrifices for little apparent gain. Britain had suffered more than 60,000 casualties in two years of fighting, with 9,627 dying on the battlefield or from battlefield related injuries, whilst another 16,251 dying from illness and disease. 35,476 British soldiers would suffer from various injuries, many of whom were maimed losing arms or legs, hands and feet, eyes and ears. Others suffered from unseen injuries to the heart, the mind, and the soul, becoming little more than husks of their former selves.

Many Britons back home had also contributed to the war effort, donating money, clothing, or foodstuffs with little expectation of recompense or restitution at the end of the war. Taxes had been increased and war time bonds had been issued by the British Government to raise revenue for the war effort. By late 1856, many Britons simply had nothing left to give to their government. In their eyes, continuing the war would only worsen their suffering and their sacrifices, and for what? A small chance to dismantle the Russian Empire, to liberate Poland and Finland and the Muslims of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Their independence would not help the Yorkshire farmers or the London merchants, nor would their freedom appease the grieving mothers and wives whose menfolk had died to liberate them.

Finally, there was the matter of India. For the past eight months, the Indian Subcontinent had been embroiled in revolt by mutinous Sepoys and traitorous Nawabs. India was the Jewel of Britain’s burgeoning Empire – generating tens of millions in revenue via Company loan repayments and priceless trading commodities such as opium, tea, spice, silk, gold, and much, much more. If the reports of this past Summer were true, however, then the situation in the Subcontinent was becoming incredibly dire. The forces on the ground loyal to London and the East India Company (EIC) were outnumbered more than three to one and were in desperate need of reinforcements. If help did not arrive soon, then those few remaining Princely states still loyal to Britain might then rethink their loyalties to London and join with the rebels.

It was clear to Palmerston and his supporters that they could not pursue both the War against Russia and the Subjugation of the Indian Rebels at the same time. They had tried and they had failed. If they continued to pursue the war with Russia, they could likely succeed - with further costs in blood and treasure, but in the process, they would likely lose everything in India. Ultimately, Palmerston would agree to make peace with Russia with the hope that foreign pressure would limit Russian gains.

British Prime Minister - Lord Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Initial armistice talks would take place in the city of Berlin on the 15th of November. In attendance were the ambassadors from the War's primary belligerents; Baron Bloomfield (Britain), Count Brunnow (Russia), Yusuf Kamil Pasha (the Ottoman Empire), as well as representatives from Austria, Count Friedrich von Thun und Hohenstein, and France, Auguste de Tallenay. Before the proceeding officially began, Russian diplomat Count Philipp von Brunnow would offer a formal apology to the Austrian Government on behalf of the Russian government, laying the blame for the entire Galician Incident squarely at the feet of Prince Alexander Menshikov and the deceased Prince Alexander Chernyshyov.

Nesselrode hoped to avert war between Austria and Russia by scapegoating the dead Chernyshyov and the disgraced Menshikov, who had been swiftly cashiered and forced into an early retirement by Tsar Nicholas. The Russian Government also offered restitution for the wayward province of Galicia, even going so far as to suggest purchasing the state outright. Austrian pride compelled von Thun to reject the offer out of hand, however, he did promise to relay the offer to his superiors for further consideration. This would certainly not erase the irrevocable damage that had been inflicted, nor did it completely alleviate the threat of war between them, but it was a necessary step towards reconciliation between their two states. With that awkward exchange out of the way, the Armistice talks officially began.

These hearings would cover a wide range of topics from an official armistice date - set for the 24th of December – ceasing all hostilities between belligerent states, and a return of all prisoners taken on both sides over the course of the conflict. Britain would also agree to immediately vacate the Kamchatka Peninsula and end its naval blockades in the Baltic Sea – minor concessions given the fast approach of the Winter sea ice. In return, all Russian troops outside Varna, Shumen, and Trebizond would break their siege works and withdrawal 10 miles from the cities’ walls – movements that were already well underway in the Balkans. However, Britain would not vacate the Åland islands nor end its blockade of Russia’s Black Sea ports, which would remain in place until the start of the Armistice to incentivize Russian compliance. Similarly, the Russians kept their troops on the southern bank of the Danube and scattered across Eastern Anatolia -albeit scaled down considerably - in the event Britain attempted to back out of the peace talks or the Austrians invaded. Lastly, both sides would agree to attend a formal peace conference in three months-time.

However, the debate over the location of where exactly this Peace Conference would take place was perhaps the most contentious as neither side wished to have a hostile power host such an important event. For that reason, cities within the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and Great Britain were rejected almost immediately. Similarly, the Kingdom of Greece’s candidacy was opposed due to strong Ottoman opposition, whilst Sweden-Norway and Hungary were naturally blocked by Russia for their own apparent hostility to St. Petersburg. Prussia would be strongly considered by both parties initially, but ultimately rejected as the British felt it was too friendly to the Russians over the course of the war and had only condemned Russia’s illegal actions in Galicia once the rest of Europe had already done so. The cities of Spain and Portugal were considered too far, and the Italian and German states were considered too insignificant.

Ultimately, the choice came down to two cities: Vienna and Paris. With Austria still threatening war with Russia, however, the Russian delegation was hesitant to name Vienna as the site of the conference. Britain too did not fully trust the Austrians either, for while they were at odds with St. Petersburg now, their historical friendship and natural affinity might predispose them towards the Russians.[1] Moreover, Vienna as a city was on the decline in the years following the 1848 Revolutions. Many of the Hungarian elements of the city departed following the war and its separation from the rest of Germany only worsened this deterioration. The French diplomat Count Alexandre Colonna-Walewski would put it best, stating that Vienna was a city on the decline, a city of the past; whereas Paris was a city on the rise, a city of the future, with a booming population, great history, exquisite art, and a vibrant culture.

Great Britain and the Ottoman Governments had no qualms with selection of Paris given their good relations with the French during the war. The Austrian ambassador, von Thun also gave his support for Paris after some persuasion from his French counterpart. However, the Russian ambassador, Count Brunnow was more distrustful of Napoleon II than his counterparts, as the French Emperor had used the distraction of this war to sure up France’s position across the globe. The Egyptian succession crisis was quickly resolved in his favor, with the ascension of Ismail Pasha to the Khedivate’s throne. He had also expanded French holdings in Algiers, whilst Algerian and Berber ghazis were ferried to the Balkans and Anatolia to fight against Russia on the Ottoman Porte’s behalf. France had similarly expanded its influence into Southeast Asia, establishing colonies in the South Pacific and forging commercial ties with the countries of Indochina.

Moreover, French material support for the Anglo-Ottoman alliance during the war had resulted in thousands of additional Russian casualties and needlessly extended the war for many weeks and months. Finally, they had applied significant financial and diplomatic pressure on St. Petersburg during the latter stages of the war, refusing to provide loans for Russia and convinced several of its allies to do the same. However, France had not taken up arms against Russia directly, nor had it imposed extreme demands upon St. Petersburg even after the Galician Incident. There was also a degree of flexibility that could be found in the French Government towards Russia as opposed to the British or Turks. After careful consideration, Count Brunnow would accept Paris’ candidacy for the ensuing Peace Conference, bringing the armistice talks to an end.

With the Armistice finally agreed to, the cursory skirmishing and raiding that had characterized the Balkan and Anatolian front lines over the last few months of the war gradually gave way. When the Armistice Day finally arrived, many Russian and British soldiers cheered for their trials and tribulations were now at an end. Former enemies would even congregate together, trading souvenirs, sharing drinks, and singing festive songs for their war was over and their reasons to fight were gone. Word would soon arrive in Tehran of Russia’s move towards peace, convincing the Qajari Government to dispatch their own emissaries to the British. Although they considered the Persians to be vile opportunists that had taken advantage of Britain’s momentary weakness, London had more pressing matters to attend to in India and quickly acquiesced to the Qajari request for peace. Nearly two months later in mid-February 1857, the representatives of Great Britain, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, the Qajari Empire, Austria, Hungary, Prussia, Sweden-Norway and Greece arrived in Paris to finalize the terms of the Peace between them.[2]

Attendees of the Paris Peace Conference of 1857:

Representing the Russian Empire –

- Russian Foreign Minister, Count Karl von Nesselrode,

- Russian Ambassador to France, Prince Alexey Orlov,

Representing the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland –

- British Foreign Minister, Lord George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon

- British Ambassador to France, Lord Henry Wellesley, 1st Earl Cowley.

Representing the Ottoman Empire –

- Ottoman Grand Vizier, Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha

- Ottoman Ambassador to France, Mehmed Cemli Bey.