Author's Note: Okay, I now I said that I'd have this update ready last weekend. It didn't happen because I am an addict and my drug is Elden Ring, which has consumed pretty much all of my free time the last few weeks.

Anyway, I managed to put this chapter together in between my play sessions over the last month, so hopefully this isn't too disjointed.

Before we begin though, I have a few things I wish to opine on.

Regarding the Olympics TTL:

While I haven't completely ruled out making Greece the permanent site for the Summer Games - they will definitely be a reoccurring host for the Games, much more so than OTL. Now the Winter Games on the other hand, will be generally based outside of Greece more often than not when they're eventually founded In fact, there may not even be a Greek Winter Games, as there are many other countries with stronger winter sports pedigree than Greece.

@Vaeius Sadly, I don't have a name in mind, it was just a reference to the OTL 1896 Olympic Games who allegedly had a Chilean runner named Luis Subercaseaux participate in the 100, 400, and 800 meter runs. His involvement is disputed, however, as he was not recorded as starting any of these races despite being listed on all three.

Regarding Greece conquering Anatolia/the Russian Civil War/events far into the future:

So minor spoiler, but I'm not planning on Greece conquering all of Anatolia, or even most of Anatolia. In fact, they'd be lucky to hold onto just the coasts of Anatolia. That said, I never said they won't try for more than they can realistically hold.

We're human and humans make mistakes. Similarly, the characters in this story are human too, they will make mistakes, they will be brash and arrogant and bite off more than they can chew and they will probably fail as a result, which I honestly think is more interesting than a story about everyone doing everything right and getting everything they want. And who knows, maybe through some massive stroke of luck, they do end up getting much more than they reasonably should and if they do, then they will have to endure all the consequences that success brings.

However, this is all many years in the future ITTL and many, many, many chapters ahead from where we are in the narrative right now, so much can and will change between now and then. In fact, the world is already quite different from OTL and will continue to diverge more and more with each passing year ITTL. So if an event like the Russian Civil War emerges in this timeline, it will not be like the Civil War in OTL, of that I am certain.

Regarding the K&G video:

I'm not a native Greek speaker, so I don't really have a basis for how to correctly pronounce anyone's names both OTL and ITTL. It could also be that the spelling I'm using for some of the names doesn't line up that well with the pronunciations used in the video either.

A large part of the problem could also be that I haven't really covered the War for Independence in much depth since I started the timeline

over 4 years ago. In fact, most of the characters featured in those first 30 chapters back then are either dead or have largely retired from public life by this point in the timeline, so it makes sense that they'd seem unfamiliar to some of you. Hell, as the timeline officially started in July 1822, I didn't really get the chance to cover the founding members of the Filiki Eteria or some of the early war figures like Alexander Ypsilantis, Athanasios Diakos, or Germanos III.

Now, without further ado....

Part 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens

The Areopagus in Athens – site of the Ancient Athenian Judicial Council

Following the latest round of elections in the Fall of 1857, the Kómma Ethnikofrónōn (the Nationalist Party) would pick up a staggering 57 seats in the Vouli - the Hellenic Legislature’s Lower Chamber - raising their majority from 81 seats in 1854 to 138 in 1857. The Fileléfthero Kómma (the Liberal Party) of Alexandros Mavrokordatos, would similarly make gains from the New Provinces, with his group earning 23 new seats, raising their total to 79 Representatives in the Vouli. However, despite making reasonable gains in this recent Election, the Liberals' share of the vote in the Lower Chamber would still decrease by almost 5%. Moreover, their situation was even worse when compared to the aftermath of the recent 1855 Snap Elections, which had seen them pick up 17 of the 20 seats allocated to the Ionian Islands, narrowing the gap between the two parties considerably from 81:56 to 84:73.

Whereas before, the abstention or betrayal of a small handful of Nationalist legislators could decide the outcome of a bill in the Liberals' favor; after the 1857 elections, the Nationalists had a massive advantage of 59 members providing for a much larger cushion in the Vouli. Moreover, as the rules of the Vouli only required a simple majority to pass legislation, they only needed the support of 109 legislators to vote for a bill; meaning that as many as 29 Nationalist representatives could break ranks with their Party leadership and still fail to stop a bill from becoming law. Moreover, they essentially had a two thirds majority within the Vouli on their own, meaning they could essentially override any veto issued by King Leopold with only a handful of Liberal defectors. With this turn of events, the Liberals effectively lost whatever negotiating power they still had within the Legislature, effectively marking the end for any formal opposition to the Nationalist Party within Greece for the better part of the next two decades. This period, extending from 1857 to 1873 would be known to posterity as the Nationalist Oligarchy.

However, in spite of the preeminence of the Nationalist Party in the Hellenic Legislature; they were not as all-powerful as they seemed. On the surface, the Nationalist Party was a socially conservative and economically liberal political party that advocated for the Enosis (Union) of the Greek State with traditionally Greek lands. Yet, buried beneath this monolithic veneer that the Party bosses and publicists presented it to be, the Nationalists were in fact quite a diverse group with many differing opinions and ideologies that would often put it at odds with itself.

Many members expressed differing economic, social, and political ideologies that conflicted and contrasted greatly with many of their peers. Some supported socialist economic policies that would see the Hellenic Government take more control over the Greek economy, enacting stricter regulations upon the private market to better the conditions of the Greek workers. Others favored a more liberal, laize-faire approach, enabling the market to regulate itself and sort out its problems on its own. Some wanted greater government involvement in the day to day lives of its citizens, whilst others wanted as little government interference as possible. A few Nationalists would even whisper of dissolving the Monarchy altogether and establishing a Republic, although they were generally relegated to the fringes of the Party.

In fact, the only unifying tenant of the Nationalist Party was the Megali Idea - the expansion of the Greek State into historical Greek lands. Yet here too, the extent of their ambitions also differed with many clamoring for the reconquest of Macedonia, Thrace, Constantinople, Ionia, Bithynia, Cyprus and the Northern Aegean Islands. Some pushed for more, however, calling for the liberation of distant Pontus, Cappadocia, and Cilicia reconstituting the old Rhomaion borders in Anatolia. A few more radical thinkers even suggested the expansion of Greece across the Mediterranean into Southern Italy, the Levantine coast, and North Africa.[1] Ironically, this support for the Megali Idea had fully permeated the rival Liberal Party by this time, effectively eroding much of the distinction between the two parties beyond minor economic and social policy differences.

One of the many interpretations of the Megali Idea

In the midst of all this, several distinct factions would begin to form under the umbrella of the wider Nationalist Party. Of these, the most boisterous were the so called

Sosialethnikistés (Social Nationalists). These members of the Nationalist Party were a vocal minority within the overarching organization who clamored for the establishment of social safety nets, greater government spending on education and healthcare, more extensive land reform, and the confirmation of worker’s rights and trade unions. They also supported a more limited expansion of the Greek state to include the Aegean Islands, Cyprus, Ionia, Macedonia, Thrace and Constantinople. Their stance towards ethnic minorities was also much more reserved and respectful, compared to the bombastic and downright xenophobic views held by some of their peers.

In total, the Social Nationalists would number 17 members who caucused together in the Vouli after the 1857 Elections. Most would come from the poorer provinces of Western Greece such as Aetolia-Acarnania, Arta, and Argyrokastro, although two would come from the Nomos of Heraklion and Chania. Incidentally, many were also former members of the short lived Hellenic Socialist Party which had first emerged in 1848, only to quickly disappear by the 1855 Elections. Whilst they initially constituted a small faction within the Nationalist Party, they were quite outspoken in their opinions and used every resource available to them to make their voices heard making them quite popular with the young and disenfranchised of Greek society for whom they fought.

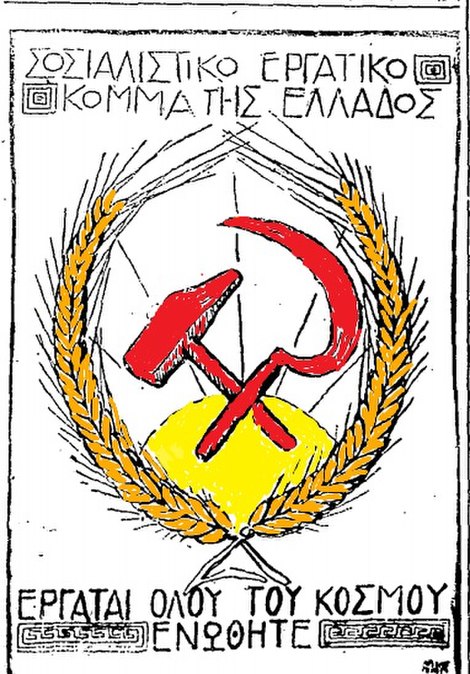

In the next elections, their numbers would more than double to 41 Representatives and continue to rise every election that, before leveling off at 52 representatives in the 1869 Elections. Because of their meteoric rise in popularity and their rather radical political agenda, the other, more conservative elements of the Nationalist Party would cooperate to suppress them. This coordinated opposition to their agenda would eventually force many of the Social Nationalists to formal break with the Nationalists and create their own political party in 1875, the

Hellenic Labor Party – an act that would mark the beginning of the end for the Nationalist Party.

The Shipwrights’ Hammer and the Farmers’ Sickle -Symbols of the Hellenic Labor Party circa 1880

The next major group, forming the largest faction within the Nationalist Party with 62 representatives in the Vouli were the

Palioí Ethnikistés, the so-called Old Nationalists. Most of these men were members of the Nationalist Party prior to the Enosis of Thessaly and Epirus with the Kingdom of Greece, in fact many were holdovers from the days of the Ioannis Kolettis regime. They were predominantly wealthy land holders and shipping magnates, rather than the fire brand speakers and philosophers that made up the Social Nationalist ranks. Whilst they normally supported limited government spending beyond its current purview, they did favor economic investments particularly those that benefited themselves or their political allies. As such, some of their members developed a reputation for nepotism and corruption in later years for their rather self-interested political agenda. Whilst their initiatives would do a measure of good for their own constituents; over time, their share of the Vouli would gradually diminish in favor of various other factions which eventually emerged from the Nationalist yoke.

The first of these groups to arise from the scandal riddled Old Nationalist Faction would be the

Anexártitoi Ethnikistés, the Independent Nationalists who quickly gathered 27 members to their cause following the 1861 elections. Like the Old Nationalists, they are generally considered among the many conservative sub-factions of the Nationalist Party. However, in comparison to the

Palioí Ethnikistés, the

Anexártitoi Ethnikistés usually fall in the more liberal end of the Conservative factions and usually tended towards the center on most policy issues. Moreover, they would portray themselves as moderates, independent of the shadowy machinations and byzantine intrigue governing the Nationalist Party Leadership.

Complicating matters were the inclusion of various other groups, like the Nationalist Republicans who desired to abolish the Monarchy and establish a democratic republic in its place. By in large, they were a minority, within a minority, as most of their members came from within the ranks of the Social Nationalists, as such, in 1857 they only boasted 5 members. Nevertheless, they would provide a distinct Anti-Monarchist flair to the group going forward. On the opposite end of the political spectrum were the Orthodox Nationalists. These were 11 of more conservative members of the Nationalist Party who advocated for the stricter adherence to traditon, the continued prevalence of the landed elite and shipping magnates, and the zealous pursuit of the Megali Idea. Generally, they caucused with the Old Nationalists, but as time passed they would begin moving in their own direction, away from the increasingly corrupt clique that led the Nationalist Party.

Beyond these four were several other sub-factions, yet they were based more on regional or ethnic identity, rather than political ideology in most cases. More often than not, these groups formed voting blocks of like-minded representatives usually from one particular region of the country such as the Moreot Nationalists, the Epirote Nationalists, and the Cretan Nationalists among others. Generally speaking, their agenda consisted of gaining greater government funding for their constituents and municipalities, usually out of genuine interest for their kin back home, although there are a few instances of Representatives using these initiatives to line their own pockets as well.

With all these competing interests and agendas, it is likely that the Nationalist Party would have failed miserably were it in the hands of lesser men. Thankfully for the Party and its supporters, its leader at this time was the venerable Navy Admiral turned politician, Constantine Kanaris who had navigated these tumultuous waters and created something resembling a modern political party. However, by 1860, Kanaris was getting old, quite old at 70 years of age. Moreover, his once robust health was not what it once was as the stress and strain of governing a country as rowdy as Greece for seven long years had begun to take its toll on the old Navarchos.

Constantine Kanaris, Prime Minister of Greece circa 1860

Adding to the old sailor’s troubles were a number of personal tragedies that had befallen his family during his tenure as Prime Minister. In no less than 12 years, he would lose three of his children between 1848 and 1860. The first to perish would be his only daughter, Maria in March of 1848, who would sadly succumb to the rigors of childbirth – something that was still incredibly perilous in that day and age even for the rich and powerful. Thankfully, the child, a boy named Konstantinos would survive, but the loss of his only daughter would weigh heavily on the Greek Premier for the next few years as she was barely more than a child at the time of her death.

The next to perish would be his youngest son Aristidis who would succumb to typhus in November of 1855. Unlike his father and older brothers, young Aristidis had joined the Army, attended the Hellenic Military Academy, and became a junior officer in 1853. Two years later, Lieutenant Aristidis Kanaris and a number of his peers would later be selected to serve as official observers for the Greek Army during the War between Russia, Britain and the Ottoman Empire. Sadly, he would never make it to the front on the Danube as he would fatefully come into contact with a number of sickly British soldiers whilst laying over at the port of Varna.

Taking pity on them, Aristidis would attempt to aid in their treatment, only to become afflicted with the terrible disease himself and perish before word had even reached Athens of his illness. The sudden death of Kanaris’ youngest son was certainly a tragedy as he was a promising young officer, but it was not fruitless, as his death would galvanize many Greek doctors and nurses to journey to Constantinople where they would care for the sick and wounded of all colors, countries, and creeds saving hundreds, if not thousands of lives in the process. This was of little comfort to Constantine Kanaris, however, as the loss of his youngest child would never stop hurting as he himself had pushed Aristidis to join the expedition to the Danube, believing it would benefit his career and broaden his horizons.

The last tragedy to befall the house of Kanaris would come in early January of 1860 as Konstantinos’ eldest son, Nikolaos was struck down by rioters in Beirut. Nikolaos had been appointed as the deputy Greek consul for the city of Beirut at the behest of his father to further Greek interests in the region. Unfortunately, the timing could not have been worse as within a month of his arrival in country, the whole Levant would explode into sectarian violence as the Muslims turned against their Christian neighbors beating, brutalizing, and murdering any they came across. Mount Lebanon was no different as the local Druze and Sunni communities, emboldened by their compatriots’ actions in Syria - rebelled against the reign of their Maronite ruler, Qasim Shihab.[2]

Caught up in all of this was Nikolaos Kanaris who had made the fateful decision to stay in Beirut and provide shelter for numerous Maronite and Armenian families seeking refuge from persecution. By extending his protection to the Christians of Beirut, Nikolaos put himself at great personal risk as rioters frequently harassed the Greek Consulate, profaning its walls and hurling rocks, roof tiles and fecal matter at its staff members as they passed through its gate. Nevertheless, his selflessness would save many dozens of lives, who were then spirited away to the hills and valleys of Mount Lebanon, or overseas where they’d be safe for a time. Sadly, tensions within the city continued to grow and the boldness of the protesters grew with it. By late August, tensions reached a boiling point, when a mob of angered Arabs arrived outside his door demanding he surrender his guests to the mob. Nikolaos refused their demands as he had time and time again, but this time, the rioters refused to leave. Emotions quickly escalated and moments later, Nikolaos Kanaris was dead, murdered in cold blood by the mob, who summarily stormed his residence and butchered all inside – be they Maronite, Armenian, or Greek - with reckless abandon.

Beiruti Protestors gather outside the home of Nikolaos Kanaris

Furious and aggrieved by the death of his eldest son, Kanaris dispatched envoys to the Ottoman government and Lebanon Emir demanding justice. Unfortunately, as Anti-Greek sentiment was on the rise in Kostantîniyye at this time, very little was done about the matter by the Sublime Porte beyond a token offer of condolences and a half-hearted apology. War between Greece and the Ottoman Empire was only averted by the considerable efforts of the French ambassador, Edouard Thouvenel who petitioned the Porte for a French led Peace Keeping expedition to restore the Sultan's Peace and bring those insidious brigands to justice.

Forming the core of this Peace Keeping Force were three French infantry regiments and a regiment of hussars under the command of General Charles de Beaufort d’Hautpoul. Alongside the French were a number of British, Prussian, Austrian, Hungarian and Italian troops with the begrudging approval of the Beiruti Government and their overlord in Konstantinyye. In addition to these land forces were over twenty warships from various foreign powers, with the largest contingent coming from little Greece. The Greek contribution to this Peace Corps was surprisingly large relative to their influence, nevertheless, they still managed to mobilize five ships including a pair of screw frigates (

VP Psara and VP

Hydra), a sailing frigate (

VP Chios), and two sloops of war (

VP Messolongion and

VP Tripolitsa). However, owing to the growing hostility between Athens and Constantinople, no Greek forces were permitted to land in Lebanon much to the chagrin of the Hellenes.

Nevertheless, the Greek vessels were quite active patrolling the waters off the coast of Beirut owing to the vigorous leadership of the Greek Squadron’s commanding officer, Antinavarchos Themistocles Kanaris - younger brother of the slain Nikolaos Kanaris. Naturally upset with the murder of his elder brother, Themistocles had few qualms meting out justice upon any rabble rousers his ships, sailors and marines came across while in theater. During the campaign, no less than a dozen "pirate" vessels would be sunk, and another 22 were harassed by the angered Greeks, who clearly had a bone to pick with rowdy Arabs.

Despite this oversized Greek Naval contingent, the other Powers would generally take the lead in the campaign on land, pacifying the region through shows of force and acts of shock and awe rather than wanton destruction and callous murders. Eventually, their efforts would pay off, leading to the surrender or flight of almost every major rebel element in the Mount Lebanon/Syria region by the beginning of 1861. With the rebellion effectively over, the Prince of Lebanon, Qasim Shihab quickly rounded up a number of prominent prisoners, executed a number of them, and shipped their heads to the Greek captains anchored off the coast of Beirut as a sign of good will towards the Athenian Government – effectively ameliorating the angered Greek Prime Minister.

French troops arrive in Beirut

Beyond these personal losses for the old Navarchos, the Kanaris Administration would also be rocked by a number of scandals and controversies around this time; chief among these being the Voulgaris Affair. In 1858, the Greek Minister of the Interior, Dimitrios Voulgaris would be accused of using Government money to buy votes for himself and several of his closest allies during the most recent elections. Voulgaris naturally refuted the charges against him and would vigorously proclaim his innocence. However, many of his colleagues would contradict the Minister and admit to their involvement in the plot, before summarily resigning from office in disgrace. By May of 1858, more than half a dozen Representatives had left office, either permanently or via extended leaves of absences, never to return.

Voulgaris remained obstinate, however, much to the chagrin of Constantine Kanaris who quickly found himself under increasing pressure to sunder all ties with his longtime ally and friend. For his part, Kanaris stayed loyal to his colleague far longer than he reasonably should have as a second rumor of nepotism, bribery, and coercion within the Ministry of the Interior conveniently emerged in late September, undermining Voulgaris’ reputation even further. With Kanaris reluctant to act, the Vouli would be forced to make him. A total of 171 Representatives from both the Nationalist and Liberal Parties would present Kanaris with a fait accompli demanding the removal of Voulgaris’ from his Ministry posting, or else he risk a vote of no confidence that would likely see him overthrown. With no other choice, the old Navarchos would accept their demands and compel Voulgaris to give up his Cabinet post and retire with honor whilst he still had some left.

Slighted at this perceived betrayal, Voulgaris would instead take the matters to the Judiciary where he would choose to settle the matter in the courtroom. Placed under a bright spotlight, the crux of the argument against Voulgaris would eventually collapse as the instigators of the rumors conveniently failed to show in court. While Voulgaris’ adversaries would claim coercion against the witnesses, he would nevertheless prevail owing to lack of evidence. Yet, in spite of this great victory, his name was forever tarnished and would never again attain the immense power and influence that he once held. Even still, Dimitrios Voulgaris remained a rather popular and charismatic figure in the Vouli with many important supporters in the Chamber. However, having been spurned by his former friend and ally, he would then focus all of his energies into opposing Kanaris.

Dimitrios Voulgaris; Minister of the Treasury (1848-1854), Minister of the Interior (1854-1858) and center of the notorious Voulgaris Affair in late 1858

Although the Voulgaris Affair was certainly the most famous example of corruption within the Kanaris Administration it was not the first he had faced, nor would it be the last. In fact, his first term as Prime Minister back in early 1850, had been riddled with controversies and scandals. None were more damning, however, than those surrounding his controversial Minister of Finance, Nikolaos Poniropoulos. Poniropoulos, a former klepht captain turned politician, was forced upon Kanaris by his old rival Ioannis Kolettis, who threatened to gridlock the Vouli unless his several of his proxies were granted Cabinet postings in Kanaris’ nascent regime - Poniropoulos being one such proxy. As his support within the Vouli was quite limited at the time, Kanaris was forced to accept the arrangement with Kolletis much to his own chagrin.

However, as he would soon discover, the agreement with Kolettis was a poison pill, as Poniropoulos would soon use his new prerogatives to manipulate grain prices to the benefit of himself and close associates. This scheme would see grain prices steadily outpace the rise in inflation, earning Poniropoulos and his allies hundreds of thousands of Drachma in the process. Naturally, this would also hurt the poor and impoverished of Greece who were already struggling to feed themselves and their families. Within a matter of weeks, most of the major cities of Greece were awash with protests calling for the removal of Poniropoulos, whilst some municipalities would report multiple riots over bread. Unable to act decisively given his own delicate grip on power, Kanaris would eventually be forced to resign, bringing about the Ioannis Kolettis Administration.

Today, many historians believe that the Poniropoulos Grain Controversy was orchestrated by Kolettis to undermine Kanaris and sink his Premiership, as Poniropoulos would conveniently retire within days of Kanaris' resignation, whilst his controversial policies were summarily revoked. While Ioannis Kolettis was long dead by 1858, his influence over the Nationalist Party remained strong as many of his cronies and underlings remained in prominent positions all throughout the Party leadership. Moreover, these same men continued to operate in a ruthlessly calculated manner, sparking numerous controversies and scandals in the years that followed. Nevertheless, they were just the tip of the iceberg as the most widespread case of Government corruption, would ironically come from a bipartisan piece of legislation; the 1859 Land Reform Act.

While on the surface, the Land Reform Act was a measure meant to protect the small landholders and yeoman farmers of Greece at the expense of the country’s large magnates and latifundia, it cannot be denied that the bill contained a massive payout to the landed elite of Greece. In return for their support for the measure establishing various protections for small family farmers, many prominent landowners would receive lump sums of cash amounting to upwards of 14 million Drachma. Officially, this was given as recompense to those who purchased land and property from the fleeing Chifliks, however, many other figures who weren’t involved in this illicit trade with the Turks were also recipients of this Government capital.

Moreover, hidden deep within the Bill were numerous carve outs and loopholes, exempting various magnates from several taxes and fees that they might otherwise had faced for their illegal actions, costing the Government millions in uncollected revenue. Finally, there were a number of promises for future Government investment into infrastructure projects in their respective provinces to mollify the landed elite. This latter measure has generally been glossed over as it was lumped in with additional provisions for the poor and downtrodden, although these handouts to the poor are relatively meager in comparison. Overall, the 1859 Land Reform Act was a mixed bag for many Greeks, as though it did strengthen protections for small landholders across the country; it also disproportionately benefited the landed elite, who were officially the targets of these new Government regulations.

Whilst corruption was certainly a problem in the Legislature, it was unfortunately endemic throughout all levels of the Greek Government. Often times, low level bureaucrats sent to gather that year’s tax revenue, would be skim several Drachma off the top, then report the reduced amount to government offices in Athens. Other times, they would dramatically under report the properties of a local magnate in return for a sizeable bribe – usually lesser than the taxes owed. As there was little in the way of Government oversight at this time, any evidence of wrongdoing would usually be chalked up to accounting errors in most instances, never to be redressed again. Local notaries were also prone to bribery and often committed the very fraud they were hired to prevent. That is not to say that corrupt government officials were not caught or punished for their crimes, but as long as they didn’t grow too bold or fail to cover their tracks effectively, then nothing would normally come of their criminal behavior. It likely didn’t help that the group responsible for investigating these crimes and arresting the alleged perpetrators, the Gendarmerie were embroiled in various controversies of their own.

As Greece did not have a proper civilian police force prior to the 1880’s, much of the responsibilities for keeping the peace in Greece fell on the Hellenic Army’s Gendarmerie Regiment who were essentially overworked, overburdened, and, more often than not, under paid. Under normal circumstances, the Gendarmerie would be tasked with policing the Army’s ranks, hunting bandits, and enforcing the Government’s authority over the more autonomous regions of Greece such as the Mani, the islands of Hydra and Spetses, and Thesprotia among others. In addition to these, however, they were often charged with suppressing popular unrest throughout the country, breaking up protests, arresting criminals, and guarding prisons. Whilst these were certainly irksome tasks, most members of the Gendarmerie were not above taking bribes to look the other way on certain issues or to go after one's rivals instead.

This latter point would become particularly egregious under Ioannis Kolettis, who notoriously used the Gendarmerie as his cudgel against his many political opponents during his Premiership. The famed Strategos Yannis Makriyannis was coerced into an early retirement by the captain of a Gendarmerie squadron who conveniently arrested his son, Dimitris for stealing the day after a particularly heated spat he had with Kolettis. Similarly, Alexandros Mavrokordatos also found himself on the wrong side of the Gendarmerie who raided his family home in Athens no less than 17 times between 1850 and 1853. Even King Leopold would find himself at the Gendarmerie’s mercy as Kolettis provided Leopold with an “escort” of Gendarmerie officers, loyal only to the Prime Minister for every one of his speeches before the Legislature (eventually Leopold would stop visiting the Vouli entirely until Kolettis’ death in 1853).

Beyond this, the Gendarmerie were also known to harass various ethnic minorities during Kolettis’ Premiership, often questioning them about their religion, citizenship, and mother tongue. If the suspect was found to be disagreeable, they would usually have their businesses disrupted, their goods seized, or their families bothered. If they resisted beyond what was expected, as happened from time to time, they could find themselves being incarcerated or beaten, or both, or worse in some rarer instances. This trend would sadly continue well into the Kanaris years, particularly in the New Provinces as the Athens worked to establish its control over Thessaly and Epirus.

Whilst the takeover of these regions was mostly peaceful, there were several government reports of “resistance” by indigenous Muslim communities against the new Greek authorities. According to some questionable accounts, Muslim bandits attacked several bureaucrats in the region of Trikala, killing five and wounding three more in late 1857. Soon after, the Turkish and Albanian communities in the area would find themselves being forced from their homes by the Gendarmerie who coerced many hundreds, if not thousands into departing for the Ottoman Empire. Coincidentally, their now vacant properties were summarily confiscated and auctioned off at a premium rate, primarily to rich land magnates with connections in high places. The continued sectarian violence in Thesprotia and its environs would also see the Gendarmerie called in to restore order, although in this case it would generally be utilized against both Albanian Muslims and Epirote Christians without prejudice.

Troops of the Hellenic Gendarmerie

Beyond these acts of political violence and coercion, there were also several instances of politicians using their clout to benefit themselves or their family through acts of nepotism. By all accounts, Constantine Kanaris has generally had a good personal record regarding corruption during his decades of public service, yet even he was not above using his office's power and influence to benefit his sons. This was done namely by influencing the Foreign Ministry, the Hellenic Navy, and the Hellenic Army to advance their careers at a quickened pace or to provide them with extraordinary experiences most of their peers could hardly dream of. Such is almost certainly the case with young Aristidis, who was barely out of the Military Academy in 1853 only to be “selected” to serve as an official observer for the Great Russian War less than two years later. Similarly, Nikolaos would see himself appointed to the consulate in Beirut, a posting generally described as plush and incredibly exotic by his peers, despite having only joined the Foreign Ministry a few years prior.

Needless to say, such allegations against Kanaris were quickly silenced followed the successive deaths of his youngest and eldest sons in 1855 and 1860 respectively. For even his most committed rivals, such talk was viewed in especially poor taste and needlessly cruel towards a man who had lost three of his children in barely twelve years. Moreover, most members of the political and social elite in Greece were guilty of the same offenses, having exploited their power, influence, and personal connections to better themselves, their families, or their friends. It was the norm for those in positions of power; not just in Greece, but all across the globe. Moreover, it was also something that was incredibly hard to prove in a court of law, as in many cases, clout and personal connections could only contribute so much to a man’s career. Unless they had the skills to succeed on their own, it did not matter who they knew or who their parents were.

For instance, whilst Panos Kolokotronis almost certainly used his office as Aide de Camp to King Leopold to implant his own son Theodoros into Prince Constantine’s inner circle of friends, his schemes would have come to naught if the two boys didn’t form a genuine relationship in the years that followed. Similarly, Alexandros Mavrokordatos was known to patronize the career of his brother-in-law Spyridon Trikoupis, appointing him to various high offices during his singular term as Prime Minister and then later sponsoring his leadership for the Liberal Party upon his retirement from public office in 1861. Yet it cannot be denied that Trikoupis was a talented orator and a skilled diplomat who would have earned such an impressive resume on his own at a later date even without the support of his Phanariot in-laws.

Though corruption, political violence, and nepotism would continue to wax and wane over the coming decades, it cannot be denied that the 1850's, 60's and 70's would be their apex in Greece. As with all things, the blame for this proliferation of corruption would fall on those in charge, namely Prime Minister Kanaris and King Leopold for not cracking down on these issues sooner or with more force. Yet in both cases, however, they were clearly elderly men on the downturn of their lives. As mentioned before, Kanaris had served as Prime Minister for nearly 8 consecutive years, during a period of immense stress and crisis across the Balkans region, all while suffering repeated losses to his family and circle of allies. Similarly, Leopold was clearly afflicted with various ailments by the start of the 1860's resulting in a slow, if steady withdrawal from public life in the lead up to his death before the end of the decade, all the while he continued to wear the heavy crown of Hellas with grim determination.

Next Time: Twilight of the Lion King

[1] In case you didn't realize, this is a reference to you my dearly beloved readers.

[2] Owing to the improved standing of the Egyptians in the Second Syrian War, Bashir Shihab was not ousted from power in Mount Lebanon. As such, he was succeeded by his son Qasim upon his death in 1850. Similarly, the Mount Lebanon Emirate was not dissolved ITTL for the same reasons, effectively becoming a buffer between Ottoman Syria and Egyptian Palestine.