So I'm not going to lie, I didn't expect to be gone from this thread for nearly 8 months. Then again, I didn't expect to be short tasked to the other side of the world on three days notice either, but that's life in the military for you.

Anyway, hope everyone's doing well and apologies for the long hiatus. While I've been rather busy for the last few months, I did do a fair amount of writing on this timeline and I actually have built up a fairly decent stockpile of completed/mostly completed chapters that I will be releasing over the coming weeks. Hope you all enjoy!

Chapter 98: Kleptocracy

A Klepht of Ottoman Roumelia

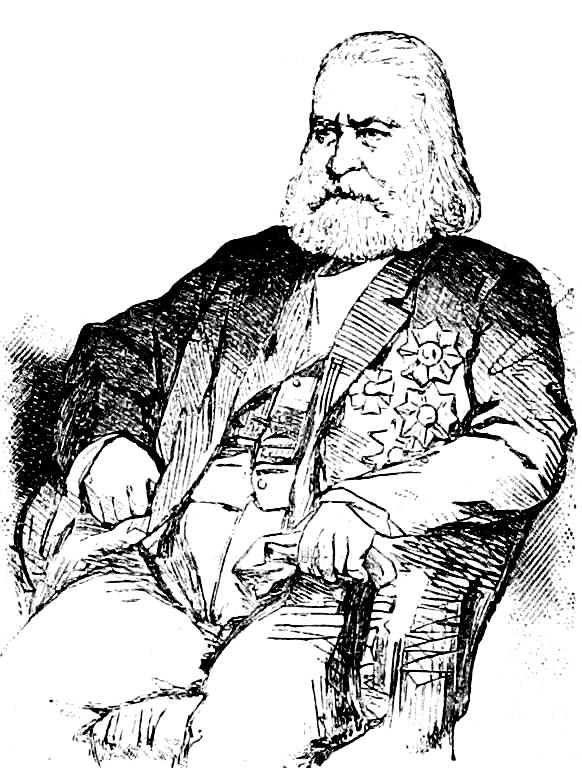

In the days and weeks following Constantine’s Inauguration as King of the Hellenes, a flurry of concern gripped the Government. Yet this worry was not due to the wide-eyed ambitions of their young new king whose gaze lay firmly upon the North and East, but rather the abrupt decision of their wizened old Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris to retire. Having shouldered the weight of the Hellenic Government for 11 consecutive years and nearly 12 in total, Kanaris was a stalwart of Greek Politics. For many young Greeks he was the only Prime Minister they could remember, second only to the great Ioannis Kapodistrias. Though his recent resume was marred with controversies, his Premiership on a whole had been incredibly successful seeing Greece expand territorially, grow economically, and flourish politically.

Although his term as Prime Minister was successful by almost every margin, his greatest achievement by far would be the signings of the Clarendon-Kolokotronis Agreement and the Treaty of Constantinople in 1855 which would see the Kingdom of Greece gain the territories of Epirus, Thessaly, the Ionian Islands and the Dodecanese Islands uniting them under the Azure and White. The additions of these new provinces would expand the Hellenic State from a paltry 60,000 square kilometers to a more impressive 90,000 square kilometers, providing Greece with more defensible borders and more resources. Additionally, with these new territories came new peoples, growing Greece’s population from a meager 1.4 million people at the start of his second term, to a more respectable 2.4 million inhabitants by 1864.

Along with these territorial and demographic expansions came an economic explosion as the GDP of the Hellenic State had more than doubled, from 198 million Drachma (7.92 million Pounds) in 1853 to nearly 410 million Drachma (16.4 million Pounds) by the start of 1864.[1] Much of this was due to the added resources and peoples of the New Provinces as the fertile fields of Thessaly were among the most productive farmlands in the entire Balkans, whilst the Ionian Islands and Dodecanese Islands were important hubs of commerce and trade in the Eastern Mediterranean.

However, these additions in territory were further strengthened and improved upon thanks to the business-friendly policies of the Kanaris Administration. Several of Greece’s port facilities had been modernized and expanded – thanks in large part to British investment, whilst the Corinth Canal - started in 1853, was finally completed in mid-1862 with British assistance, opening up new avenues of trade throughout the region and expanding their capacity to ship goods across the Eastern Mediterranean. There had also been a fair amount of land reform throughout Greece during his tenure as Prime Minister, which would finally do away with the dreaded Chiflik system in Thessaly and Epirus empowering a new generation of small landholders across the country.

Finally, his skillful stewardship of the Greek state had seen the Nationalist Party rise to the pinnacle of Greek politics where they would remain largely unchallenged for years to come. Their grip on power was so complete that the legislative gridlock that had defined the Vouli since its inception was virtually non-existent from the mid-1850s onwards to the early 1870s. Regular appropriation bills which normally took months to pass were passed with routine efficiency, major pieces of legislation were drafted, amended, and passed into law with remarkable swiftness, whilst regional Governors, Ministers, and political appointees were appointed with ease. Although this uni-party system would eventually grow irksome for most Greeks and cumbersome for the Nationalist Party Elites, it nevertheless, served them well through some troubling and trying times.

Lithograph of Constantine Kanaris in early January 1864 only a few weeks before his resignation from Office

Despite these great successes, however, Kanaris’ leadership of the Greek Government was not without its faults, especially in more recent years. His questionable handling of the notorious love affair between King Leopold and Fotini Mavromichalis had earned him the ire of many within the Vouli. Kanaris had routinely dismissed rumors of the King’s infidelity until long after it became public knowledge, making him out to be a doddering old fool in many eyes. His intransigence was made all the worse by the comparatively light punishment he levied upon Leopold in the affair’s aftermath, with many describing it as a mere slap on the wrist.

The 1858 Voulgaris Corruption Scandal was also a highly contentious moment for the Kanaris Government. Kanaris and Voulgaris were longtime friends and political allies who had forged their relationship during the trials and testaments of the Revolution and tumultuous early post Revolution period. Yet, in the eyes of many Greeks, Voulgaris was a crook who had exploited their friendship to his own benefit politically. Even as more and more rumors of Voulgaris’ corrupt behavior came to light, Kanaris continued to stand by his Interior Minister in defiance of the Vouli who clamored for his ouster. Only once public sentiment had firmly turned against Voulgaris – and the Vouli threatened to remove Kanaris from office, would the Old Navarchos relent to the Legislature’s pressure and ask Voulgaris to resign. This stalwart support for his former compatriot would ultimately result in rounds of humiliating investigations into Kanaris’ own affairs by his political adversaries who sought to demonize and humiliate him. Eventually, the ensuing fallout would reveal that Constantine Kanaris was completely innocence in the Voulgaris matter, yet it cannot be denied that he was left weakened after the whole debacle.

Finally, his oversight of the Lebanese Expedition in 1861 was also draped in controversy. Although he argued that he was defending Greeks and Greek interests throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, many suggested that he was overly involved in the planning and management of the expedition - owing to the death of his eldest son. According to his critics, this vendetta against the Lebanese Arabs would lead to the premature deployment of the Hellenic Navy to the region before an agreement had been reached with the Ottoman government, nearly sparking a war for which they were ill-prepared. Although an accord would be hastily concluded permitting limited Greek involvement in the French led Lebanese Expedition, they were restricted to a purely naval mission and only along the Levantine coast from Acre to Tartus. After several months, the expedition would be successfully concluded, yet its only real success - apart from the sinking of a few worthless “pirate vessels”, was the further antagonism of the Ottoman Government.

Speaking of the Ottomans; relations between Athens and Kostantîniyye had steadily declined during Kanaris’ tenure as Prime Minister. Although they had never been strong to begin with, Kanaris’ inability or rather his unwillingness to oppose Greek irredentism at the Sublime Porte’s expense eroded whatever good will had grown between the two states since 1830. The Turks would on numerous occasions accuse Kanaris of turning a blind eye to brigands operating out of Greek territory and of weapons smugglers crossing the border to deposit their illicit goods with Christian partisans.

Whilst few Greeks cared for the opinions of the Turks, these infringements upon the Ottoman Empire’s sovereignty did irk the United Kingdom who still sought to buttress the Sublime Porte against the ever-expanding Russian Empire. As cordial relations with the British were of much greater importance to the Greeks, mounting pressure from London would eventually force Kanaris to - at least in public - take a much sterner stance against the more militant nationalists in his Government during the later years of his Premiership. Whilst he would never actually renounce the Megali Idea or their accompanying claims to Ottoman territory, he would suspend all state sponsored subterfuge against the Ottomans and he would publicly oppose war with the Turks for the remainder of his time in office.

Finally, there was the matter that Constantine Kanaris was rapidly approaching his 74th birthday in 1864. He was old, very old and Kanaris felt every bit his age. His youth had been ruled by conflict and war fighting against the Turks in the War of Independence and supporting further rebellions across the Ottoman Empire. He witnessed firsthand the destruction of his beloved homeland of Psara, losing many friends and family at the hands of the Turks. His later years were governed by political infighting and the rigors of administrating a nascent country. Both had taken an immense toll upon him; body, mind, and spirit. Beyond this, he had watched three of his children predecease him and more recently his wife of 47 years, Despoina who had passed away from a sudden illness utterly devastating him. He was tired and wanted nothing more than to spend his remaining days in peace with what family he had left.

Thankfully for the old Navarchos, King Constantine would accept his resignation, on the condition that he stay on past his Inauguration. King Constantine’s later writings would confirm that this delaying action was merely a show of respect as the he had already made his decision on Kanaris’ replacement. However, King Constantine’s critics would argue that the German interloper did not wish to draw attention away from the pageantry of his coronation. Either way, it was decided that Kanaris would stay on until the end of February to help ease the transition process for the young King. Two weeks after his investiture King Constantine accepted Kanaris’ formal resignation, offered him a firm handshake and kindly pat on the shoulder. With his work finally done, Constantine Kanaris would retire to a small villa on the edge of Athens where he would live out the remainder of his days in relative peace, surrounded by his friends and family. Like the great Ioannis Kapodistrias before him, Kanaris would occasionally stir from his rest to offer words of wisdom to King Constantine or to provide whatever counsel he could to his successors before ultimately succumbing to old age in November of 1875.

Constantine Kanaris had set a high standard for Prime Minister of the Hellenic State, one which many men might fail to reach. Thankfully for Greece, the man that would ultimately succeed Kanaris was up to the task. He was no stranger to King Constantine or Constantine Kanaris as he had been a constant presence at the Royal Court during the King’s youth and through much of Kanaris’ Premiership. He had served as Aide de Camp and Adjutant to the late King Leopold, he was a Strategos of the Hellenic Army, Minister of the Army, and Deputy Prime Minister. He was King Constantine’s old mentor and the father of his closest friend. He was Panos Kolokotronis.

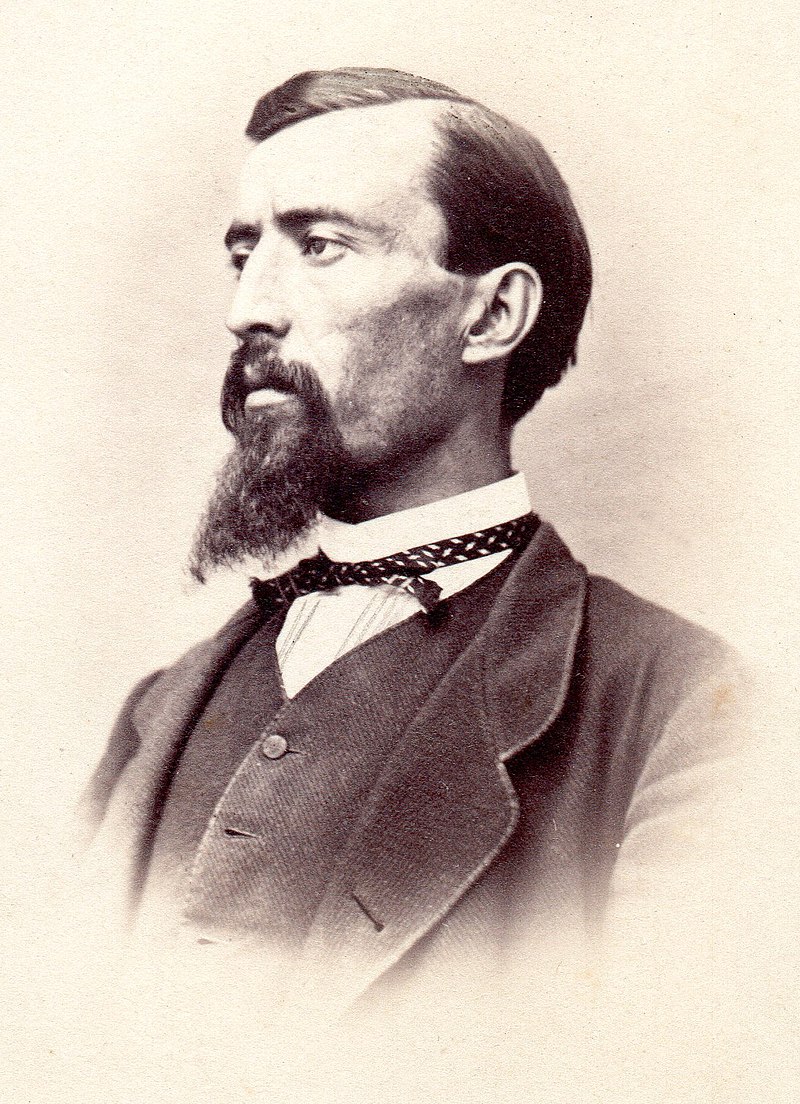

Panos Kolokotronis circa 1852, 7th Prime Minister of Greece

Born on the island of Zakynthos in 1800, Panos Kolokotronis was himself the son of martyred War Hero Theodoros Kolokotronis. Though he would live in his father’s shadow for the first few months of the war, he would emerge as a great leader in his own right during Ibrahim Kavalali Pasha’s invasion of the Morea. Leading a prolonged guerilla campaign against the Egyptian Prince; Panos would finally strike a decisive blow against Ibrahim Pasha in 1826 near the town of Gytheio in the Mani where he and his men captured or killed nearly half of the enemy Army. Thereafter, Kolokotronis and his allies would go on the offensive reclaiming nearly all of the Peloponnese from Egyptian and Ottoman occupation, culminating in the surrender of Patras in early 1828. With the evacuation of the Egyptian Army in late 1827/early 1828, the War in the Peloponnese came to an end and so too did Panos’ involvement in the War, apart from a single raid into Central Greece in early 1829.

Following the Revolution, Panos would begin shifting from the life of a klepht and warrior into that of a career soldier and civil servant, when in the Summer of 1830, he was selected to serve as the new King Leopold’s Aide de Camp. Though this lowly posting likely insulted his great pride and could have incited a terrible controversy, the young Strategos remained surprisingly humble during his time of service to the King and made the most of his opportunity to learn the finer points of statecraft and administration from Leopold.

His patience would be rewarded, as within a few short months, he was named as the King’s Adjutant and Chief Military Adviser a role he would continue to hold for several years, before replacing the retiring Markos Botsaris as field commander of the Hellenic Army. However, his time in this position would be limited as he soon joined the Government of Ioannes Metaxas as Minister of the Army in 1841. In these roles he maintained his close working relation with King Leopold and would visit the Royal Manor on occasion to wine and dine with the King and his family.

It was around this time that he would make his impact felt on the young Diadochos Constantine who, being shunned by the cold and overly disciplined Leopold, came to admire the famed Panos Kolokotronis as a surrogate father figure in lieu of his actual father. Unlike Leopold, Panos was quite respectful to young Constantine and always wore a kindly expression on his face despite his imposing stature and fierce reputation. Most importantly, he introduced his own son Theodoros into the household of the young Diadochos Constantine. The two were of similar ages and though they differed greatly in temperament and character, they would prove fast friends. Whilst Panos would come and go in service of the King and Hellenic Government; Theodoros would remain a constant part of Diadochos Constantine’s life, becoming the Agrippa to Constantine’s Augustus.

An Enduring Friendship;

King Constantine (Center) and Theodoros Kolokotronis (left) in their later years.

It comes as no surprise then that the newly enthroned King Constantine chose Panos Kolokotronis to be the first Prime Minister of his reign. He trusted the old Strategos and believed him to be the right person for the job. He wasn’t wrong in this belief either, as Panos Kolokotronis was a living legend and one of the few remaining Heroes from the Revolutionary War. Moreover, he was widely favored by several dozen legislators within the Nationalist Party and he had extensive name recognition among the Hellenic people, making him a natural choice for the position. Most importantly, he was a capable statesman with experience serving in the Ministry of the Army, the Interior Ministry, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at various points over the past 23 years.

This is not to say that Panos Kolokotronis was universally adored, as he certainly wasn’t. He had many rivals throughout the Hellenic Government. His infamous Kolokotronis Pride had earned him many enemies within the Vouli, primarily among those of the Liberal Party and the Conservative Wing of the Nationalist Party. To these men, Panos Kolokotronis was a vainglorious braggart, a vagabond and a cutthroat who spared no expense to get his way (be it by treasure spent or blood spilt). In 1847, he famously attacked the former Finance Minister Ioannis Orlandos with his cane for having the audacity to support closer economic relations with the Turks. Although the Prime Minister at the time, Alexandros Mavrokordatos threatened Panos with censorship and expulsion from the Vouli for this act of violence; his staunch support from the King and large following in the Legislature made such a move impossible.

Panos Kolokotronis was also unabashedly biased towards his fellow Peloponnesians, using his great influence to benefit his allies, granting them high ranking positions in his Ministries or among his staff. Meanwhile, few Islanders, Roumeliotes or Phanariotes ever entered into his service. Those that did were often his former compatriots from the War or members of his wife Eleni Boubouli’s extended family. He was also notorious for his nepotism, using his power and prestige to advance the careers of his relatives and close friends with his brothers Konstantinos and Ioannis being constant figures in any Government that he himself was a part of. Despite all this, even his detractors and political rivals would agree -albeit begrudgingly - that Panos Kolokotronis was the right man for the job. Thus, when King Constantine approached Panos Kolokotronis and requested that he take the office of the Prime Minister for himself, he graciously accepted.

Within a few short weeks, the new Prime Minister had selected his cadre of ministers – primarily from amongst his political allies, personal friends, and immediate family members. His Deputy Prime Minister would be his younger brother Ioannis (Gennaios) Kolokotronis. A former soldier and Senator, Ioannis had served as an irregular during the War for Independence during his youth. Although not as famous as his elder brother, Ioannis had quietly built a solid career in the Hellenic Bureaucracy serving in the Ministries of the Interior and the Ministry of the Army over the last 20 years. Moreover, Ioannis was resoundingly loyal to his brother Panos and had faithfully served in his staff for many years. Rewarding his brother’s continued fidelity, Panos would also appoint Ioannis to the important posting of Interior Minister as he dared not appoint anyone else to the position.

The prestigious Office of the Foreign Minister would be filled by his other brother, Konstantinos Kolokotronis who was himself a respectable statesman in his own right. Contrary to popular opinion, it was Konstantinos, not Panos who had helped fashion the famed

Clarendon-Kolokotronis Agreement with Viscount Palmerston and the Earl of Clarendon in 1855. Through his shrewd negotiations with the British, Konstantinos would successfully wring the Ionian Islands from London’s grip along with a number of financial concessions and investments. His adept diplomacy would also secure the much sought after territories of Thessaly, Epirus and the Dodecanese Islands during the latter

1855 Treaty of Constantinople.

Continuing this trend of appointing close family members and friends to his Cabinet, Panos’ would appoint his brother-in-law, Georgios Yiannouzas to the office of Minister of the Navy. Meanwhile, his close friend Thrasyvoulos Zaimis would become head of the Education and Religious Affairs Ministry and the Achaean Efstathios Iliopoulos was appointed Justice Minister – yet another ally of the Kolokotronis family. To solidify his grip over the Nationalist Party and provide some semblance of continuity, Panos Kolokotronis would appoint a few holdovers from the previous Kanaris Government to other important cabinet positions with Dimitrios Christidis retaining his role as the head of the Finance Ministry, whilst Ioannis Antonopoulos and Benizelos Roufos would be retained as Ministers without Portfolios. The latter would retire from public service within the year however and was eventually replaced by the former Mayor of Spetses, Nikolaos Mexis, another of Panos’ allies.

Cabinet of Panos Kolokotronis (1864):

- Prime Minister: Panos Kolokotronis

- Deputy Prime Minister: Ioannis (Gennaios) Kolokotronis

- Foreign Minister: Konstantinos Kolokotronis

- Interior Minister: Ioannis (Gennaios) Kolokotronis

- Finance Minister: Dimitrios Christidis

- Justice Minister: Efstathios Iliopoulos

- Education and Religious Affairs Minister: Thrasyvoulos Zaimis

- Army Minister: Panos Kolokotronis

- Navy Minister: Georgios Yiannouzas

- Ministers Without Portfolio: Ioannis Antonopoulos, Benizelos Roufos and Nikolaos Mexis

Owing to the predominance of former klephts, armatolis, pirates and privateers within the Kolokotronis Government, historians would later term this regime as the “Kolokotronis Kleptocracy”. Despite this title, Greece would be remarkably stable under the Kolokotronis Administration and see very little in the way of

major corruption allegations or violent outbursts between its Political Parties until its firery demise in 1872. Much of this was due to the relatively seamless transition between the Kanaris and Kolokotronis governments as very little changeover took place below the Cabinet, with many lower and mid-level bureaucrats retaining their posts. Even many deputy ministers who were themselves political appointees retained their former positions or were moved into lateral offices. That said, the transition between the Kanaris Government and the Kolokotronis Government was not entirely painless as Kolokotronis’ adversaries in the Legislature would frequently resist him.

Chief among these adversaries was the wisened statesman Alexandros Mavrokordatos who had helmed the opposing Liberal Party for the better part of the last 25 years. Although he had fallen into ill health by the 1860’s, Mavrokordatos still remained passionate and obstinate in his rivalry towards Panos Kolokotronis and his opposition to the Nationalist Party agenda. Though the Liberal Party was smaller by far than the Nationalist Party with 86 Representatives to 131, his control over the Party was firm as few members of his caucus broke ranks with their leader. Without a supermajority in the Vouli, Mavrokordatos and his allies could successfully delay the Nationalist agenda through every mean available to them from protesting vital votes to filibusters until compromises were met or amendments were made. However, Mavrokordatos’ declining health and eventual death in late September of 1864 threw the Liberals into confusion and disarray, from which they would not soon recover.

The timing couldn't be worse as the subsequent General Elections in November of that year would be for all intents and purposes, a massacre as the Liberals were soundly defeated, losing more than 20 seats to the Nationalists. With this defeat, the Liberal Party was effectively relegated to irrelevancy in Greek politics providing Panos Kolokotronis and his Nationalists with their much sought after supermajority in the Vouli. Yet this was both a blessing - giving them complete control over the Vouli, and a curse as the Nationalist Party would suffer from growing fragmentation and diverging ideology within its ranks. Ironically, this defeat in the 1864 Elections would also serve as an important development for the Liberal Party which was forced to undergo its own period of reform and soul searching in the wake of this terrible defeat.

Next Time: Captains of Industry

[1] Shout out to

@Lascaris for his great tables detailing this information way back in post number

3654.