So I know I said I would cover the entire Indian Rebellion in one chapter, but this part quickly ballooned into something much longer than I initially anticipated. As such I've decided to split it into two separate chapters, one which I'll be releasing today and the other which I'll be releasing later this week. After which, the narrative will finally return to Greece and we can see how things are developing there. Hope you all enjoy!

Chapter 87: The Devil's Wind - Part 1

British soldiers fending off an Indian attack at the Battle of Badli-ki-Serai

The end of the Russian War in the Spring of 1857 would not bring about the end of the British Empire’s troubles as one theater of conflict still remained: India. Following the Mutiny at Agra in early February 1856, the traitorous Sepoys initially hesitated for several days as they considered their options. Although tensions had been rising with the British in the years before the revolt, many did not think of themselves as patriots or freedom fighters. Many simply wanted their rights and customs to be respected, whilst many more wanted higher salaries and more opportunities for advancement in the Military. Any chance they may have had of attaining these goals had been quashed with their Mutiny at Agra.

Passion had overcome their base desires and British blood had been shed by their hands. There was no going back for them now. If they tried, they would surely be enfettered by the vengeful Europeans and executed for their crimes against the East India Company and the British Crown. At this point, they could only go forward, forward to war, and forward to the liberation of India. With their resolve restored, the Mutineers departed Agra for the Imperial city of Delhi.

The decision to go to Delhi was a simple one for the Mutineers. The Walled City had been the seat of the Mughal Empire for generations and though its grandeur had waned in recent years – owing in large part to British expansion in the Subcontinent, it still remained the formal residence of the Mughal Emperor. Now little more than a figurehead, Bahadur Shah Zafar II was still a well-respected figure in Indian society. Many of the Sepoys wished to liberate the Emperor from his British jailers and hoist him upon their shoulders as the Emperor of a free and united India, giving their people a leader to rally around.

Adding fuel to this drive towards Delhi was the recent decision by the British Commander in Chief of India, Major General Major George Anson to begin moving European troops into the city. Officially, this decision had been to defend the City against Persian raids, but in the eyes of most Indians it was yet another act of encroachment on their freedom by the British. Marching like men possessed, the Mutineers would arrive outside Delhi eight days later on the 17th of February.

Their fast pace would catch the British garrison completely off guard as they initially mistook them for reinforcements coming up from Calcutta. Although Anson had heard of the “protests” at Agra, he initially dismissed it as an isolated event that could be easily contained to the local area with the forces at hand, not a rapidly expanding revolt that had already reached his doorstep. Anson’s decision making was also undermined by a desperate need for more troops as Qajari raiders had struck deep into the Punjab recently, reaching as far as Faisalabad and Gujranwala before being turned back by British and Indian forces. Although he doubted future attacks could reach as far as Delhi, he still needed to ensure the city was safeguarded against any future Persian incursion.

Nevertheless, by the time the Rebels arrived outside Delhi’s walls, the city’s garrison was still severely undermanned, numbering only 4 understrength regiments – 1 British (the 32nd Regiment of Foot) and 3 Indian (the 9th, 10th, and 12th Bengal Native Infantry Regiments).[1] For their part, the Rebel Regiments maintained their guise of loyalty until they passed through the city’s gates before swiftly turning on the unsuspecting British soldiers, killing several dozen before they had a chance to react. Despite the suddenness of the mutineers’ attack, the British would initially hold their ground against the rebels. For a brief moment, the 1856 Indian Rebellion looked as if it would be a minor footnote in history, that is until General Anson foolishly ordered the three Native Regiments under his command forward to crush the rebels. This was a deadly mistake.

Not wishing to fire upon their countrymen, many instead opted to join with the Mutineers, turning the tide of the engagement decisively in the rebel’s favor. Emboldened by their actions, many citizens of Delhi would also take up arms alongside the mutineers and attacked any Briton in sight – be they British or German, soldier or civilian, man or woman, grown adult or young child. Innocent babes were ripped from their mothers’ arms and dashed upon the rocks, wailing British womenfolk were hacked to pieces like fresh meat in a butcher’s shop, all the while their husbands, fathers, and brothers were left to despair as their families were brutalized and victimized by the frenzied masses of Delhi before being torn limb from limb themselves. The Delhi mob would not spare their “traitorous countrymen” either as any Christian Indian convert was cruelly cut down by their neighbors and friends with gruesome ferocity. Even those who had committed no offense against their countrymen were cut down for the audacity of having grown wealthy and affluent under British rule.

With the anarchy rapidly engulfing the entire city, Anson ordered his remaining men to steadily fall back to the Red Fort where they would secure the Emperor Bahadur II, his court, and the Imperial treasury against these “revolutionaries”. Officially this brazen order was made to protect the Indian Emperor and prevent his fall into mutineer hands, but in truth, Anson likely recognized the importance of the Emperor and the Palace which he could use against the mob. With Emperor Bahadur in his custody, Anson believed he could either force the Rebels into submission or facilitate his own escape from Delhi. With some amount of difficultly, the remaining men of the 32nd would fight their way to the Palace complex and gain possession of the Mughal Emperor, most of his extensive broad, and many of his courtiers.

The Fort was thereafter inundated with refugees from the city; East India Company (EIC) bureaucrats and their families, loyal Sepoys and Christian Indians who all flocked to the fortress seeking safety from the Rebel Sepoys and the rioting populace of Delhi who hunted them throughout the city. Some soldiers and civilians would also flee to the nearby Flagstaff Tower on the edge of town, but by late-afternoon, the last pocket of organized resistance outside the Red Fort was quashed by the mutineers. Before they did, however, a young telegraph operator - whose name has sadly been lost to history - sent out a desperate message to Umballa and Meerut, and from there onto Calcutta and Bombay. The message reads as follows: “

The Sepoys are in revolt. Delhi has fallen. Send help immediately.” This message would repeat three more times, before the young man was finally cut down by the Sepoys and people of Delhi.

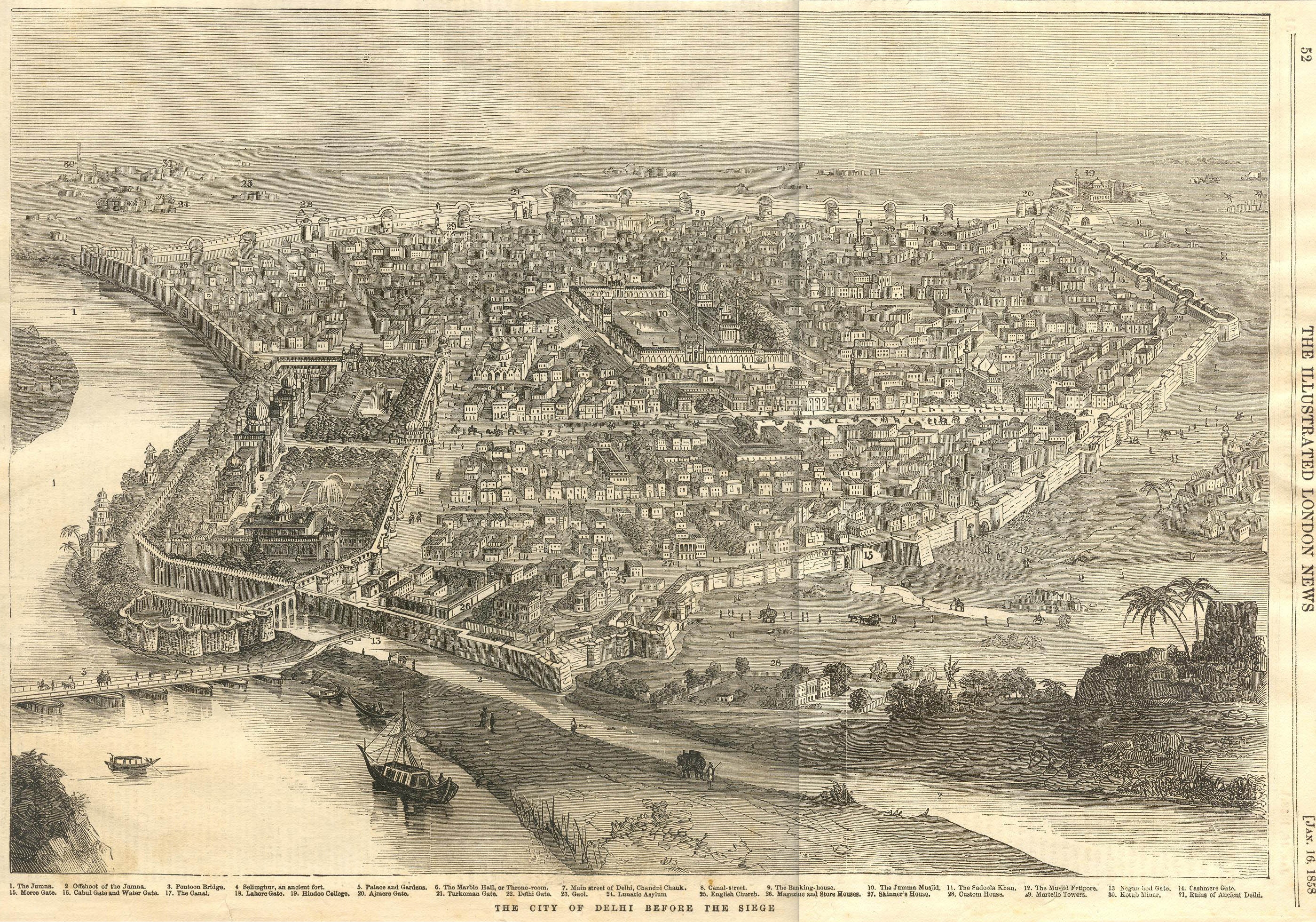

The Walled City of Delhi in the days before the Rebellion

With the remaining British troops trapped inside the Red Fort, the Sepoys declared victory and proclaimed the independence of India. News of Delhi’s fall to the Rebels soon spread like wildfire across all of India as Sepoy regiments of the Bengal Presidency revolted en masse against their British officers; slaying those that they could and driving off the rest. Of the 86 Bengali Native Regiments of Foot, all but 9 would join the Mutineers in their fight against the British, whilst all but one horse regiment would join with the rebels. The situation in the other Presidencies was less severe as only three regiments would rebel in the Bombay Army and only a single regiment of the Madras Army would mutiny. However, their loyalties were still thrown into doubt after the events at Agra and Delhi; and though they continued to profess their loyalty to the EIC and the British Government, there was no way of truly proving that. As such, they were largely relegated to garrison duty by the fearful British for the next few weeks whilst their true allegiances were determined.

Making matters worse, the Princely States of Oudh, Rewari, Banda, Ferozepur Jhirka and a dozen more would side with the mutinous Sepoys and cast-off British hegemony. The timing could not have been worse for the British as two Bengal Regiments of Foot, the 32nd (British) and the 71st (Native) were already en route to Lucknow to detain the incompetent King of Oudh, Wajid Ali Shah, when the news arrived from Delhi of the Rebellion. Seizing upon the news, the 71st immediately turned on the British and were quickly joined by the people of Faizabad and local Oudh warriors. Despite a valiant effort, the soldiers of the 32nd were swiftly reduced one by one until little more than a third were left. Those that remained made a fighting retreat to the nearby town of Basti where they were quickly besieged by their former comrades.

Added to this were the continued raids by the Qajaris into the Punjab and Baluchistan, tying down numerous units of the British Army in India that could have otherwise been sent against the rebels. The war with Russia did not help matters in India either as regiments originally destined for the Subcontinent were instead redirected to the Balkans and Anatolia to fend off the Russian offensive there. By the time of the rebellion, British troops in India were stretched recklessly thin, with a single European regiment covering the massive expanse from Calcutta to Dinapur. Help would not arrive in the region until late Summer when elements of the British 3rd and 6th Divisions finally began arriving in the Subcontinent after receiving a special dispensation from the Egyptian Governor to cross the Sinai. However, depleted as they were from the War with Russia and exhausted from their long journey, the 3rd Division wouldn’t see any meaningful action until late October at the earliest, whilst the 6th was a green unit that still needed extensive training. In the meantime, nearly all of Northern India, from the Punjab and Lahore to Bihar and Jharkhand was in open revolt against the British, with pockets of unrest emerging almost everywhere else.

British troops besieged near Basti

All was not lost for the British however, as their leadership in theater was more than up to the task of containing the Rebellion. Then Governor-General of India, Lord James Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquise of Dalhousie had learned of the events in Delhi mere hours after they had taken place, thanks to the installation of telegraph lines all across the Subcontinent.[2] Although the Sepoy Revolt can be blamed in large part on several of his ill-conceived policies, the Scotsman was an incredibly tenacious worker and a capable administrator who had weathered similar crises during his 7 long years as Governor. Once word of the rebellion at Delhi arrived, he acted swiftly, issuing orders to disarm any and all Native Regiments found to have sympathies with the Rebels.

Sepoys of confirmed loyalty were provided with stipends and bonuses to their pay in recognition of their continued faithfulness, whilst other units of more moderate loyalty were dispatched to the border with Persia to distract them and relieve the British units garrisoned there. Dalhousie would also send word to London and the Governors of the Cape Colony, Australia, and New Zealand requesting immediate reinforcement be it men or material. In the meantime, he would use his authority as Governor-General to redirect a regiment of foot (the 45th) coming out from Australia and he called upon the marines of the Royal Navy stationed in India for service on the mainland.

Dalhousie would also surround himself with a number of capable deputies, such as Lord John Lawrence, Chief Commissioner of the EIC, who was himself a talented diplomat and negotiator in the Company’s employ. Thanks to Lord Lawrence’s efforts, the British were able to quickly secure the support of the Gurkha Kingdom of Nepal, which promptly dispatched 18 Regiments of Gurkhas to relieve their embattled British allies. The Gurkha people were rugged mountain men, who had proven themselves to be especially fierce warriors during their wars against the British nearly forty years prior. By the 1850’s, however they had become staunch allies – their relationship improving greatly from the appointment of pro Anglo ministers within the Nepalese Government and a begrudging respect for the Gorkhas by Westminster and the EIC. Marching down from their mountains, the Gurkhas would quickly relieve the British forces trapped at Basti and begin fighting their way towards other besieged British regiments across the region.

Several weeks later in early April, Lawrence would work wonders yet again, when he managed to pacify the Princely States of the Punjab, reminding them of Britain’s leniency and respect for their local autonomy. Ironically, the ongoing war with the Qajari Empire would also help the British in this regard as most Sikh Chieftains considered the British to be their benefactors and protectors against the Persian raiders. Finally, Lawrence played up the cultural and religious differences between the Sikhs and their Hindu and Muslim neighbors, who had been antagonizing them long before the rebellion began back in February. Thanks to Lawrence’s efforts, another dozen regiments would be raised to combat the Rebellion and with their assistance, the British would manage to mitigate the Revolutionaries’ appeal to the Ganges basin.

The British also had a decisive advantage in weaponry, as the much-maligned Pattern 1852 Enfield Rifle was a tremendous force multiplier for the British, compared to the incredibly antiquated Brown Bess musket still used by many Sepoys.[3] With its improved accuracy and range of up to 900 meters, a trained soldier wielding the Enfield could normally kill or maim 2 to 3 adversaries before they even came into firing range of their enemies’ firearms. Although loyal men were in short supply, the Enfield was not as the Sepoys (both rebel and loyal) overwhelmingly shunned the weapon. Rumor was that the Enfield’s shot and powder cartridges were greased with beef tallow or pig fat – ingredients that were highly offensive to both Muslims and Hindus and liable to damn their souls. Whether this rumor was true or not – evidence would say that it was – the result was the same; the British were corrupting the morals of the Hindi people and leading them into eternal damnation.

To rectify this and undermine Rebel propaganda, Dalhousie and his acting Commander in Chief – owing to the absence of General Anson - Major General Patrick Grant began working on an alternative cartridge greasing for the Enfield. After testing several alternatives, they would eventually settle upon a more acceptable ghee grease or vegetable oil. The opening of the cartridges would also be changed to better accommodate the Sepoys, with the user now tearing the cartridge open with their hands as opposed to their teeth. Overall, these changes would satisfy many of the regiments of the Bombay and Madras Armies, largely resolving their complaints with the weapon and bringing about their return to British service by early Summer. Most, however, would still be used in secondary roles garrisoning the South or protecting the Western Frontier to avoid any further defections. Nevertheless, a handful of Native Regiments would venture north alongside the now freed up British Regiments of the Bombay and Madras Presidencies by late Summer.

Governor-General of India; Lord James Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquise of Dalhousie (Left),

Chief Commissioner of the East India Company; Lord John Lawrence (Center),

and Acting Commander in Chief of India; Major General Sir Patrick Grant (Right)

Finally, the British had a significant advantage in military leadership over the Rebels as many of their officers were veterans of numerous campaigns, with some boasting service records all the way back to the Napoleonic Wars. Although the Sepoys were incredibly potent fighters, they had often been limited to company grade positions within the EIC’s Armies with higher field and General staff ranks going to European officers exclusively. As such, the Rebel Sepoys usually had difficulty controlling any mass of men larger than a battalion in combat. Those that did rise to higher levels of commandd had often achieved their positions due to seniority and tenure, not merit or skill. Some veteran Sepoys like Bakht Khan and Ghosh Muhammad were capable leaders, but they were a rare exception.

The Indian Nawabs were often worse as their rank and social status often inclined them to positions of military leadership despite lacking any formal experience in the modern art of war. They frequently disregarded the advice and stratagems of the more professional Sepoys, whom they derided as up-jumped peasants and cowardly traitors could not be fully trusted. More often than not, the Indian Nawabs would devolve into infighting amongst themselves as petty rivalries and disputes between opposing feudatories prevented any measure of cooperation or subordination on their part. The most striking case would be at the battle of Lucknow in mid 1857 when the craven King of Oudh abandoned the field of battle leaving the Zamindars of Hathwa, Jagdishpur, and Kalankar to face the British alone, resulting in their defeat and capture. This wasn’t entirely the norm, however, as the Maratha Peshwa Nana Saheb and his attendant Tantia Tope were renowned Indian commanders who would go on to defeat the British on various occasions with a good degree of tactical prowess and ingenuity. Sadly, they were the exception to the rule as most Nawabs relied upon their numerical superiority to overcome the British and even then, they would only do so at a great cost in lives.

Worse than this, however, was the complete breakdown of discipline within the burgeoning Rebel Army. Prior to the revolt, discipline and esprit de corps had been almost exclusively maintained by British sergeants, men who were now either dead or under siege by their former compatriots. Naturally, order and cohesion within the ranks gradually dissipated without their influence – especially in the midst of battle, although some of the more veteran regiments would maintain their ranks better than the greener units.

Making matters worse, the Sepoys were far outnumbered by the poorly equipped and poorly trained irregulars who had joined ranks with them. Those troops raised by the Indian Nobility were often arrogant, foolhardy and controlled by passion rather than sound thinking. They rarely cooperated with the more experienced Sepoys, often leading to piecemeal attacks spurred onward by boyish enthusiasm and manly bravado rather than tactical thinking and planning, only for their courage to be quickly dashed with a whiff of gunpowder and lead from the British Enfields. Unused to the rigors of a modern battlefield, panic would quickly consume these ad hoc brigades, cause them to break and flee for their lives, leaving the remainder greatly demoralized.

“These ruffians are more akin to a troupe of Brigands than a proper Army.”

– British General Patrick Grant on the hosts of the Rebel Nawabs

Despite the general expansion of the Rebellion into much of Northern India, the main focal point of the conflict would remain on the city of Delhi. The continued defiance of the British within the Red Fort would be mark of shame for the Rebels as little more than a thousand soldiers, bureaucrats and Christian Indians held off the better part of six thousand Sepoys and nearly forty thousand Delhi townsfolk for weeks on end. Initial attempts to storm the Fortress had failed miserably, forcing the Rebels to besiege the Palace complex. During this lull in the fighting, Anson would haul Emperor Bahadur out before the mob and provided him with a script calling on the rebels to throw down their arms and return to their homes peacefully. To hear their beloved Emperor parroting the words of the British was a disheartening blow for the Rebels as they saw him as their leader. Discouraged, many would desert the siege works around the Fort, leaving the lines thinned, but generally still intact.

A week later on the 1st of March, Anson brought the Emperor out before the people of Delhi once more, declaring that they had been led astray by a few dastardly fiends within their ranks, and that they should end their violence against their British friends and allies. A few more civilians and Sepoys would depart, but the effect was noticeably weaker than before. Several days later, Anson would haul Bahadur out yet again for a third and final time. On this occasion, Bahadur’s speech was much more incendiary, calling on the people to turn against the Sepoys and surrender them to the British, calling them criminals, murderers, and traitors. Enraged at this display, the people of Delhi instead turned against their Emperor, believing him to be no more than a British puppet. They accused him of cowardice and treason against his own country and people, before pelting him and his British attendants with rocks until he was finally led away in disgrace. Anson’s gambit had failed miserably.

As the siege continued deeper into March, the situation within the Red Fort became increasingly dire for those trapped within its walls. The once lavish food stores within the Palace were quickly running out – despite being designed to feed the Mughal Emperor and his massive family, they were unable to support nearly a thousand people for weeks on end even after strict rationing. Ammunition was also running low, the Red Fort had not been used as a military site in years, with most stores of powder and shot having fallen to the rebels at the beginning of the siege. Moreover, a handful of courtiers within the Emperor’s inner circle had been providing the Rebels with intelligence on British patrols within the fortress, their numbers, weaponry and organization. Worse still, on the 6th of March, the Emperor’s eldest living son, Mirza Mughal broke free from his British guards and leapt from the Red Fort’s walls into the Yamuna River.

Despite the fast currents of the mighty river, the prince was plucked from the waters by the Rebels only to be promptly imprisoned by his supposed saviors. However, in an impassioned speech the Mughal Prince denounced the British as foreign interlopers who raped and plundered fair India and called on every man, woman and child to support him in driving the Europeans back into the sea. Buoyed by his words, the rebel sepoys and people of Delhi proclaimed him Emperor of India and struck against the Red Fort with renewed vigor. Time after time they would force their way onto the walls, only to be driven back time and time again by the British, but by the end of March, the British were down to half their original strength, food was scarce, and ammunition was even scarcer. Talk of surrender was now commonplace within the Red Fort and despite his better judgement, Anson began considering it as well. However, help would soon arrive from the West.

Before the Red Fort had been completely surrounded by the Rebels back in February, General Anson dispatched a dozen riders to inform the rest of the Bengal Presidency of the burgeoning crisis and request immediate reinforcements. Most of these men would be captured and killed by the Rebels before they made it out of Delhi, but three would successfully escape, reaching Lahore, Peshawar and Multan where the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Bengal European Infantry Regiments had made their respective camps. Owing to the ongoing conflict with Qajari Persia, the 2nd and 3rd Regiments could not be immediately withdrawn from the border to relieve Delhi, but the 1st was not at such risk and was ordered to march within a fortnight.

The First Bengal (European) Fusiliers Regiment marches on Delhi

Their advance on Delhi would not go unnoticed, however, as Indian resistance steadily increased as it approached Delhi. Chief among these would be the Nawab of Rewari, Rao Tularam Singh who immediately joined the Rebellion once news arrived from Delhi. Levying a force of 5400 warriors to oppose the British, Rao’s forces would meet the 1st Fusiliers near the village of Rohtak. Despite their superior discipline and weaponry, the British were outnumbered nearly 6 to 1, and were themselves besieged by the Rewaris at Rohtak. The battle of Rohtak would continue off and on for another two and a half weeks before help finally arrived in the form of the Sikh Regiments of Ferozepore and Ludhiana which had come to assist the British. With their combined power, the British and Sikhs pushed back the Rewaris and, after a week of rest and recuperation, they continued their advance on Delhi arriving outside its walls on the 27th of March.

The arrival of these three - admittedly understrength - regiments would not intimidate the Indian Rebels as more and more Regiments of the Bengal Army journeyed to Delhi with each passing day. By the end of April, no less than 17 regiments of infantry and 10 regiments of cavalry had amassed within the Imperial capital, with another 34,000 Indian irregulars scattered across the region. However, the arrival of this small relief force would raise the flagging morale of the British garrison within the Red Fort as many of these Sepoys were now forced to guard the city’s outer walls instead of attacking the Palace’s walls, forcing their less capable comrades to pick up the slack. Two weeks later, the 2nd Regiment of Bengal European Infantry and another regiment of Sikh Infantry would arrive on scene with the 1st Bombay European Regiment reaching the British camp the following day, raising the total British strength outside Delhi to over 5,200 soldiers. Although Dalhousie and Grant had few troops to spare, they too recognized the great importance of Delhi and had concentrated all forces they could spare against it.

With these forces in hand, General Grant would prove quite aggressive in fighting the Indians over the next month, forcing a crossing over the Hindon river, seizing the heights of Badli-ki-Serai west of Delhi and razing many of the outlying communities within sight of the Indian capital. Their most inflammatory act, however, would be the execution of any so-called seditionist his troopers found, with many being strapped to the ends of cannons and blown to pieces as the guns were fired. Others were put to the torch or hung from makeshift gallows in clear display of the Delhi garrison. Many hundreds of combatants and civilians were slain by the aggrieved British in revenge for the deaths of their countrymen, with their mutilated corpses being left upon the hills north of the city. Enraged by these acts, the people of Delhi demanded that Mirza Mughal sally forth to challenge the vile British and punish them for their crimes.

However, the leading Sepoy commander, General Bakht Khan urged caution as the British had entrenched themselves atop the Badli-ki-Serai, a prominent ridge a mere 6 miles west of Delhi. This strong defensive position that was made stronger with the arrival of the 1st Brigade of Bombay Horse Artillery which had force marched from Gujarat only days before boosting the British ranks to roughly 6,000 men and providing them with a number of siege guns. Bakht and his subordinates were accused of cowardice by the Nawabs of Rewari and Banda and once more urged their Emperor to march against the British. As his legitimacy was solely dependent upon the will of the people – people who were demanding action, Mirza could not refuse them and thus he ordered his “armies” northward against the British. All told, Mirza Mughal would march forth from Delhi with 16 regiments of Sepoy Infantry, 8 regiments of Sepoy cavalry and around 20,000 auxilliaries to face off against General Grant’s army at Badli-ki-Serai, whilst the remainder maintained the siege on the Red Fort.

Sultan Muhammad Zahir Ud-din (Mirza Mughal),

21st Mughal Emperor (disputed) and Nominal leader of the Indian Rebellion of 1856

As the Indian army approached their position, the British busied themselves with the construction of various trenches, breastworks and caltrops to funnel their adversaries into a prepared kill zone. Although a veteran commander would have recognized this, Mirza Mughal was not a military man and overlooked the importance of scouting or maneuverability. Instead, he would order a frontal assault against the well-entrenched British and their Sikh allies, hoping that his superior numbers and the fervor of his men would overwhelm them. Despite their extensive preparations, the British were very nearly overrun by the Indians, who outnumbered them by more than 4 to 1. Yet it was here in the heat of battle that the veterancy and professionalism of the British troopers paid dividends as they held their ground in spite of the great mass of humanity before them. Firing volley after volley of rifle rounds into the charging Indian mob, cutting down hundreds if not thousands before they even reached the foothills of the ridge. As the bodies began to build at the bottom of the ridge, more and more fighters began to waver on the Indian side, with some even breaking entirely. A victory was within General Grant's grasp.

Yet their moment of triumph was not to be as Bakht Khan then released his Sepoys upon the unsuspecting British, catching them in the flank and routing the green Sikh regiments within minutes. Contradicting Mirza Mighal’s orders of a frontal assault, General Bakht had instead led his soldiers around the British fortifications. While this would result in his late arrival on the battlefield, it would enable him to hit the British where they were most vulnerable. The British would fight on for another few moments before the order to retreat was issued at which point, they began a fighting withdrawal northward from the battlefield. By midafternoon the battle was over, the Rebels had won, but at a great cost. Of the roughly 31,000 soldiers and irregulars in the battle, nearly 11,000 were dead, wounded, missing or captured, with most falling upon the troops of Rao Tularam of Rewari and Ali Bahadur of Banda. In comparison, the British and their Sikh allies fared slightly better, only suffering around 3,800 casualties although this amounted to more than half their entire force.

The Sepoys bore the fewest casualties given their limited involvement in the battle, but they would boast the greatest single loss, as their commander Bakht Khan had been shot through the heart whilst leading the decisive attack on the British flank. Although his death would galvanize his troops and bring about their victory that day, his loss would be felt in the weeks and months ahead. His deputy, General Ghosh Muhammad had been struck in the shoulder whilst chasing down the fleeing British, prompting his men to end their pursuit of the Britons and tend to their wounded commander. Despite the loss of their leader and their pivotal role in the battle of Badli-ki-Serai, the Sepoys were derided by their comrades for their tardiness and failure to pursue the British – completely disregarding that they had just been mauled by the British rearguard.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Badli-ki-Serai, the remains of the British-Sikh Army would withdraw northward into the Punjab where they would regroup and await additional reinforcements. This decision would effectively doom General Anson and the few remaining British forces still in Delhi, who were effectively out of ammunition and desperately short on food. Hoping that the recent battle had sufficiently deterred the Indians, Anson offered to surrender the Red Fort to the Sepoys on the condition that all those within the fortress be allowed to leave the city in peace. Feeling magnanimous after his recent victory, Mirza Mughal acquiesced, however, he would demand that the British give up their weapons, that the civilians within the Fort take only the clothes on their backs, and that his father, the “former” Emperor Bahadur be delivered into his care. Although Anson did not trust the Rebels to keep their word, he had few options left and accepted Mirza Mughals terms on the 1st of May 1856.

Anson was right to be suspicious. When the appointed time came, the British soldiers departed the fortress, followed by the officials of the EIC, their families. Last to depart were the Loyal Sepoys and Christian Indians who had sought shelter in the Red Fort. The sight of these “traitors” made the blood of every patriotic Indian in the growing crowd boil. They demanded retribution against these blackhearts who had sided with the foreign devils over their own countrymen. The crowd began hurling rocks, roof tiles, spoiled fruit and animal feces at the column. Emotions escalated and soon brawls had broken out in the streets of Delhi. When Anson attempted to protest this ill treatment to Mirza Mughal, he was summarily bludgeoned and beaten to death by the Emperor’s guards.

Panic quickly set in among the British column as the mob soon turned their attention to them. Those at the front attempted to force their way out of the city, whilst those nearer the back attempted to fight their way back to the Red Fort. Most were simply slaughtered in cold blood by the people of Delhi. By nightfall, the carnage would finally subside. Of the 457 souls who had left the Red Fort that morning, only 62 remained. Most of these were servants or family members of Mirza Mughal, whilst only 17 Britons would escape alive to tell the tale of Mirza Mughal's betrayal. In a cruel sense of humor, Mirza Mughal would order the bodies of every slain British soldier and civilian thrown outside the walls of Delhi, thus fulfilling his agreement with the late General Anson.

Seizing upon the news of these victories, the rebellion would expand further across the subcontinent. In Gwalior, the Anglophile Maharaja Jayajirao Scindia was deposed by his traitorous advisors, who promptly joined the rebellion against the British and declared their loyalty to the new Delhi Government. The Princely state of Jhansi would also join with the Rebels in late May as the young Maharaja, Damodar Rao was but a small child under the complete control of his treacherous retainers. The Princely States of Jaipur and Jodhpur would erupt into chaos as rival factions sided with the British and rebels respectively, whilst many more would be subject to violence and upheaval. The British would attempt to respond to these latest defections as best they could, but after the debacle at Badli-ki-Serai there was little they could do.

Next Time: The Devil's Wind - Part 2

[1] I should be point out that British regiments at this time were little more than bloated battalions, so these formations are roughly equivalent to 800 soldiers on average.

[2] Dalhousie was a big proponent of the telegraph and had lines constructed across the subcontinent during his tenure as Governor-General of India.

[3] Incidentally, many of the British units in India also used the Brown Bess at the time of the OTL Rebellion, although they were quickly phased out in favor of the Enfield as soon as it became available.