Hundred Days II: The Way Forward

What has happened down here is the winds have changed

Clouds roll in from the north and it start to rain

Rained real hard and rained for a real long time…

Louisiana, Louisiana,

They’re tryin’ to wash us away

- Randy Newman, “Louisiana 1927”

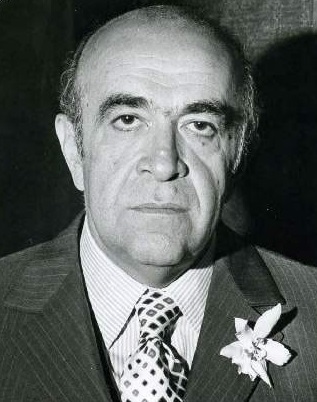

Sargent Shriver was always good for a smile, especially at times like this. Shriver and Armand Hammer sat opposite one another in sculpted tulip chairs within a hotel suite — suite? Floor — Hammer owned, relaxed and in good humor as the hi-fi across the greatroom played Frank Chacksfield & His Orchestra’s svelte tones without a trace of irony and the two men nursed snifters of brandy fortified back in the Belle Epoque. Armand Hammer, multimillionaire philanthropist, corporate impresario, amateur promoter of US-Soviet relations, and sometime political fixer for the Republican Party of all people, beamed back at Shriver from under Hammer’s big square glasses. That was typical; when you dealt with Sarge, usually a good time was had by all. Clouds roll in from the north and it start to rain

Rained real hard and rained for a real long time…

Louisiana, Louisiana,

They’re tryin’ to wash us away

- Randy Newman, “Louisiana 1927”

Shriver knew how to use that to advantage. They had talked art and travel and family already. Now Shriver waved the hand in which he held his brandy and called attention to the whole point.

The administration had a plan, Shriver said. No, not just a plan: a deal, really. Who would make sense as the man to sell this deal to the right people? Why Shriver’s old chum Armand, of course. It’s a good time to be useful, Shriver went on. A lot of my fellow Democrats have questions they’d like to ask about all that money last year. Here Shriver meant the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars Hammer had funneled to CRP for Richard Nixon’s election, meant to keep up Hammer’s bona fides as a Republican, grease the wheels for Hammer’s personal dealings with the Soviet Union, and lobby for smoother relations with Hammer’s friends in Moscow who went back to his days as a doctor in the wild, sometimes bloody post-revolutionary Soviet Union of the Twenties, some now in the Politburo itself.

It’s the twilight of the old ways of doing business, said Shriver. All the campaign funny money created… difficulties that weren’t easy for the new administration, with so much on its plate and often limited leverage in Congress, to help brush aside. It would take some quid to keep Hammer’s quo out of a courtroom. The nice thing was, both men reflected, that Sarge was just the sort of person who could finesse that situation. Shriver leaned forward, always a bit larger than he seemed when he was relaxed, and got down to business.

The administration wants to make a deal, said Shriver expansively. A private word between parties, handled by a messenger trusted on both sides, could smooth things over and speed things up. The same kind of special contacts that had gotten Hammer in dutch with Congressional investigators could make him invaluable here. That way the latter might, just maybe, cancel out the former. It was a big enough deal, Shriver assured his cagey friend. It offered the chance to bind the superpowers in a new kind of dependence on one another that might help ramp down the Cold War and make new kinds of trade across the Iron Curtain possible.

What’s the in, asked Hammer. Grain, said Shriver.

Sarge went over the background; he liked a good story. In ‘72, as both men knew, the Soviet Union suffered a catastrophic grain harvest. Not only were any surpluses for sale abroad to earn foreign cash lost to bad weather, but what Moscow needed for animal feed and bread in the state-run stores as well. It was a grim blow just as the economic officers of the Politburo pushed for more conversion to feed grains that would yield extra meat protein in the Soviet diet, a symbol of Communist abundance.

Soviet buyers lit out on the international markets to make up the losses. Among other things, and before the several moving parts of the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and State came to the same conclusion, Soviet contracts swept up American stocks on hand and struck a double blow. The first was to taxpayers, who paid the difference because Moscow’s men finalized their contracts before the open markets noticed their work and lowered prices as a consequence. The higher prices were good for farmers but subsidized out of public debt. Second, American consumers paid again at the supermarket. The loss of so much US grain meant that bread, milk, and beef, for starters, all spiked their prices and drove up broad-based inflation to boot. Some caustic observers called it “the Great Grain Robbery.” Despite the short term relief for Soviet commissars and consumers, neither side was well served. If bad weather struck again after the ill will over ‘72, both sides could suffer.

That didn’t have to happen, Shriver went on. The White House had a plan. Hammer knew, surely, of the major farm bill the administration was backing in Congress. This plan was a second prong of the effort, a corollary abroad. Shriver wanted Hammer, with his practiced decades of schmoozing pliant Soviet officials, to pitch a deal. Not just for Moscow but in fact for COMECON, the economic bloc formed by Soviet-aligned socialist states that stretched from the satellite governments of Eastern Europe to places like Cuba, Mongolia, and North Vietnam. The deal would create a long-term commodity agreement between the United States and COMECON, with the Soviets of course in the lead. Each year COMECON would purchase American grain at a fixed total price. With a phrase borrowed from arms control, each year COMECON would have “freedom to mix”: different nations could buy different volumes within the total, and each nation could buy a different combination among five fixed types of cereal grains.

Then came the interesting bit. The price of the actual grain would come in under the total bill of sasle. In a normal year, the COMECON nations would make up the difference between what they laid out for the grain itself and what America charged by buying United States Treasury securities. Those purchases would subsidize the prices payed to American farmers and help push overseas demand for Treasury paper that would finance the United States’ national debts. In crisis years, COMECON countries would be allowed to purchase fewer securities and more grain within the same total price while Washington upped its own share of the farmers’ subsidy. As crisis conditions settled the price mix would swing back to normal. The two sides would invest directly in one another: the U.S. would give price and supply stability to COMECON, while COMECON would juice the global market for Treasury bills.

Hammer nodded along as Shriver spun the tale, hands wafting through the air like an actor’s or a painter’s while the brandy snifter tagged along. When it comes to this we’re new in town, observed Shriver, or at least the President is. You on the other hand, he added to Hammer with a conspiratorial grin, are a devil Moscow knows very well. If you sit down at Kosygin’s dacha, or Kirilenko’s, or even old Leonid’s himself, and lay this out, they’ll listen. We need them to listen. With a pause, Shriver’s face fell for effect as he added: you need them to listen, too. Shriver let the thought of Congressional investigations linger in Hammer’s anxious mind, then his cheeks rose again, beaming. Even when he made a threat, Sarge said it with a smile.

On Capitol Hill, the first prong of George McGovern’s intended revolution in food policy plowed ahead. With the rather grand title of the Food and Farming Renaissance Act, McGovern’s people had slipped the first draft of a bill into the House the Monday afternoon after inauguration through a carefully chosen stalking horse, Rep. Bill Roy of Kansas’ 2nd District. A farm-state liberal like McGovern himself, Roy had higher ambitions — for the governor’s mansion in Topeka, perhaps even to poach Bob Dole’s seat in the Senate — and a lead on this issue could serve him well. It drew attention right away. Co-sponsors signed on as they read in detail, first Bob Bergland of Minnesota and John Culver of Iowa, then the fairly liberal Republican Mark Andrews of North Dakota and four more Democrats, and when they tacked on the dour security of Walter B. Jones, Sr. from North Carolina they knew they were on to something.

The FFRA was no mere farm bill. It drew together George McGovern’s long years of passion, policy work, and personal conviction about the fundamental importance of both America’s abundant food and its endangered small farmers, and made them manifest. For one, it absorbed Sargent Shriver’s promised deal for Armand Hammer in its language, backed by millions more to expand the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Agency, restructure the Food For Peace program McGovern had run for John Kennedy into a central division of the United States Agency for International Development, and make a permanent committee on global food security chaired by the new Secretary of Peace part of the National Security Council apparatus.

FFRA also authorized permanent reserve inventories to be held by designated local cooperatives recognized by the USDA and established with the department’s help. There would be a fund for disaster payments across the board on USDA commodities. The FFRA would stand up a Commodity Supplemental Food Program designed to provide surplus food to poor Americans, especially families with children. More money would go towards Parity Price Supports for overseas sales. The Fifth Title of the FFRA would function as a separable National Agricultural Research, Education, and Teaching Policy Act to set federal standards and support for publicly-funded research and agricultural extension. The Seventh Title authorized a Rural Development Agency, through which funds would flow for environmental conservation, low-interest loans for urban renewal in small market towns, and financial supports for cooperative electrification and other co-op service provision. (The ingratiating young Undersecretary of Agriculture for Rural Development, Bill Clinton, would administer the RDA from his office.)

Unlike some of President McGovern’s more controversial ideas, to which he was wedded by principle but with which he had less practical background, when it came to the FFRA the South Dakotan was on home turf. It showed. First of all in its bipartisan support: alongside freshman Nebraska Democrat Terry Carpenter, like the new president an unexpected victor in November, the principal sponsor of the Senate version was McGovern’s odd but frequent ally on food policy Bob Dole of Kansas. In the House there was more difficulty with urban Democrats, finally soothed by the breadth of the Commodity Supplemental Food Program, than with stodgy committee chairs who often hailed from districts both rural and Southern. Even Hale Boggs made clear that, on farming at least, here was an issue where Hale’s “boys” and the hippie-lover in the White House could do business. McGovern himself wanted to single out the FFRA as “hundred day” legislation, part of that mythic political ad campaign in which every new president engaged; odds looked good.

There was, however, a hitch. A significant portion of the monies that would fund the new programs, especially the Title Five and Title Seven series operations, would come from a powerful change in the government’s subsidy structure. In line with McGovern’s own views and the Democratic Party platform as well, the FFRA would end subsidies to operations larger than “family-type” farms, and to corporate operators who only ran secondary product lines in agriculture as tax write-offs. As conservative legislators prepared to use quarrels over just what a family-type farm was to snare the plan in committee, the President intervened.

Working together with USDA economists around the clock in early Feburary, Jean Westwood and Doug Coulter produced language that the Kansans, Dole and Roy, could introduce in a second draft of the House and Senate bills before markup. It gave a common, federally-defined standard for the elusive new unit of farming. That was bigger, physically, than some of McGovern’s closest allies expected, but still in the grand scheme paled against the largest Western landowners, or ranchers who grazed on federal land to expand the range of their herds, or especially the holdings of outfits like Cargill, the giant of American corporate farming, or Commerce Secretary Dwayne Andreas’ old employers at Archer Daniels Midland.

That was where the fight came. The National Chamber of Commerce funded stemwinding speeches in Congress and pamphlets distributed out of corner stores in the farm belts about just how much farmland, and how many farm workers, depended on the big players. For a short time the dour, hardline Republican Roman Hruska of Nebraska filibustered the Senate bill on grounds that naked advantage for small operators in localized areas would breach the Dormant Commerce Clause that said one couldn’t play state and local favorites in interstate trade. In the end, with Speaker Albert plus Mike Mansfield in the Senate both standing firmly on top of any efforts to field alternative legislation, it was the big boys who moved. Not to back down, rather to shift their weight sideways: after enlightening discussions with their lawyers, outfits like Cargill restructured their holdings around tenancy leases for parcels sized in line with the new federal standard. Private giants like the horizon-spanning King Ranch down in Texas (still family owned) carved up their land titles among relatives and shell companies.

There were still barriers: in some cases the biggest players really did have to sell out to smaller buyers and resume a role as wholesalers or middlemen, and a decent portion of the money the White House hoped to save was brought round for the new programs. It wasn’t perfect — there would have to be some adjustments, and more cash from the planned tax reforms. But the first true farm-state president in decades signed the FFRA into law near the end of March. Unlike some events that drew more ink and attention, and to George McGovern’s satisfaction, this truly did mark out a different future for the ways and means by which the nation and the world would be fed.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

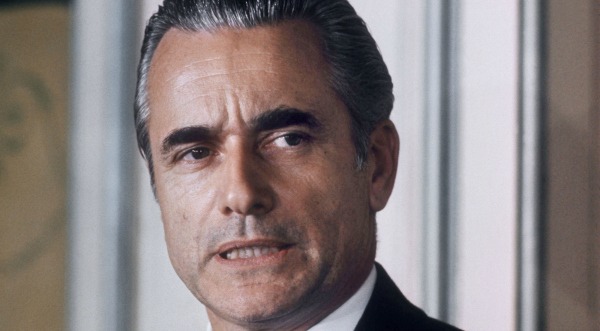

They said a few words about Lyndon first; it seemed the thing to do. They talked about the war, too, the subject that seemed to linger despite every effort to cast it out. McGovern had come a little earlier from a meeting with the bulldog faced Army two-star, Bob Kingston, in charge of what the military called the Joint Personnel Recovery Center, the small body of varied specialists from language and jungle survival to forensic pathology who were ordered to dig deep in Indochina and come back with any American prisoners hidden away or, more likely, a fuller account of America’s dead. It had been the subject of some grueling and detailed talks in Paris for the team chaired by Ball and Salinger. The administration continued to hold a line on restoration of military aid to Saigon while Thieu fumed about the demand for multi-party elections in the fall. Now, on that subject and many others, President McGovern sat on the couches of the Oval Office with his old friend and mentor the Arkansas fireplug William Fulbright, dean of the Senate on foreign policy and namesake of the grants that sent American scholars abroad to learn from the wider world. Fulbright was in an expansive mood.

“That’s all certainly true. What it comes back to, Mr. President, is…” Fulbright twisted his glasses in his left hand as he did sometimes and weighed his words. “George, you’ve got to learn to brag.”

The president’s sharp eyes sparked a moment in surprise and curiosity, a little wary. He asked Fulbright to elaborate and the senator was happy to. You really have done a hell of a lot with all this, Fulbright went on. Quite a hell of a lot. We had two presidents who told the country we’d never get this far in to Indochina, and two more who said they’d get us out, and here you are the first one who has actually done it. No one’s had a leash this tight on Thieu since the Kennedy boys installed him in the first place. You have delivered American prisoners from some very dark holes where they had been for years because you were able to push reparations through Congress. Hell, when there was a chance all that would go wrong on you, you were even willing to eat your own words and send the marines to get as many of them as you could which would’ve been a terrible gamble. You withdrew the last of our forces in-country in an orderly fashion, and you’re willing to let those folks over there get on with creating their own future. It’s a lot in a short time.

But you have no one out there really telling the story, Fulbright added. Sure, you have officials who do press conferences and Cy Vance or Salinger goes in front of reporters to give them the latest facts but that only implies what matters. Sometimes you will need to come out and say it. Otherwise facts are nimble things, they can get away from you if they’re left untended. McGovern nodded acknowledgment of what Fulbright had said. I think the American people have an opportunity to look around and see what we’ve done, the president replied, or what we’ve started to do. There are facts here that speak for themselves. Among them that we’ve worked very hard to pay attention to things as they are, not go off half-cocked with doctrines or opinions. And I think these fine people doing the work deserve the chance to give that information to the public so they can understand it and see where things stand. Much as I hate to say it, there are also things we ought to just keep close to our vests. You talked about the marines, or retaliation if Hanoi didn’t play ball about our prisoners. Well, if there are any more out there we still might have to do something about it, I just promised Major General Kingston whatever support his operation deems necessary to recover the remains of our people or anybody who’s still alive. If we talk to much about swinging a big stick we could lose any element of surprise, or scare North Vietnam or the Pathet Lao or whoever out of cooperating. We ought to continue to take this step by step. It’s still the right thing to do.

Fulbright smiled at the president he’d known since McGovern’s first months in the Senate, and kept his counsel. Facts might be stubborn things, Fulbright thought to himself, but not everyone judged them in the same way, or even saw them through the mist of preconceptions. He’d have a word with Mankiewicz at some point, maybe with Gary Hart if it looked like the chief of staff wouldn’t use it as a political football — Hart had brought up the same issue in one of the last meetings of the Group on the South Vietnam withdrawal. Time would surely educate President McGovern, he thought with some real affection for this decent man stuck with the biggest job in the world. The question was how painful that education would be. Another time, perhaps.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Well thank God for New York traffic laws, said Pete McCloskey when it was all over. He had a point. The National Security Agency had done their job to a fault; maybe this was a new day in the world of covert surveillance. Beyond that, the NSA and FBI had partnered as though they meant it, with swift, effective chains of communication and command. It was practically an advertisement for what the new gang in the West Wing wanted out of intelligence reform. Yet even then what really saved the day was the fact that, if you just left a car by the curbs of New York with the meter void, it was going to get towed. Nothing else but the stubborn enforcement of rules that justified unionized public employees’ paychecks would have done the job in time. That raised some issues.

It hadn’t started with traffic tickets in Manhattan. It hadn’t started at home at all, but rather halfway round the world in Sudan, where only in the past couple of years had the United States even restored diplomatic relations so that there were American officials, or Americans in any numbers, to be found in the country at all. Now came personnel traffic among diplomats around at the end of winter, one of those times when the Foreign Service vagabonds shuffled off to new countries, even new continents, at the bidding of a new administration far more determined than the one before it to let the sensible, slightly patrician agents of American reason guide policy rather than rely on coups and counterinsurgency.

Every fresh face overseas was meant to betoken that change: in Sudan that involved a formal reception for the new ambassador, a bespectacled career diplomat named Cleo Noel. The outgoing Deputy Chief of Mission, Curt Moore, who had effectively run the embassy for some time, would toast both Noel and the McGovern administration’s desire to pull Sudan closer in to Arab-Israeli diplomacy. With the US outpost in some physical disarray — it was a young station and a work in progress — the Saudis were kind enough to host. Noel, together with Moore who had a mutual admiration society with senior Sudanese officials, plus the new DCM Robert Fritts who’d just jetted in from Indonesia, all turned up alongside some usual suspects from Khartoum’s little diplomatic community. Despite a wicked haboob, one of the dust storms that kicked up off the red-brown plains that stretched far beyond Khartoum’s horizon, the Saudi legation was calm and cool, the mood festive.

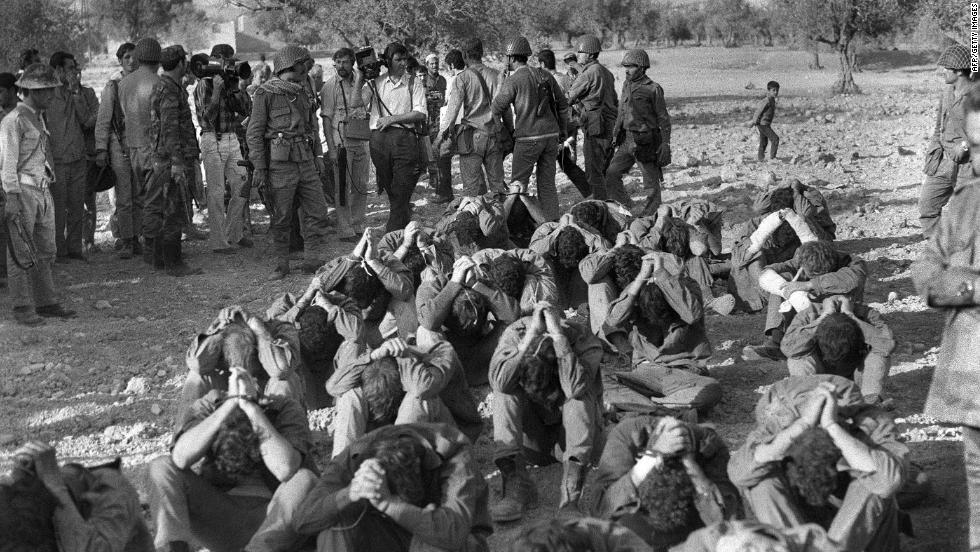

It did not last. The seven well-armed Palestinian fedayeen who strode into the embassy and seized the party guests as hostages acted in calm execution of a months-old plan. They served Black September, a militant offshoot of the mainline Palestinian Liberation Organization but also an off-the-books force of wet-workers for senior PLO leadership, useful when they wanted to strike with some deniability at the West, or hurt Israeli in ways sparked moral outrage like the slaughter of athletes in Munich. Black September had torn a path through headlines for more than a year and a half, most recently the Olympic tragedy, a wave of letter bombs in Europe and Africa, and a frankly bungled attempt to invade the Israeli embassy in Bangkok that turned into a bloody shootout with Thai authorities.

Now they meant to exert leverage on King Hussein of Jordan — to these young fighters the butcher of Palestinians in the 1970 campaign that gave the group its name — and on the new administration in Washington. The masked attackers shooed most of the party guests out of the building (the Soviet ambassador made an operatic, and mildly heroic, fuss on behalf of his captive colleagues from the West) then made both a singular demand and a singular threat. Jordan would release several dozen Palestinians imprisoned terrorists, or the three American diplomats Black September had in hand would die.

Washington had dealt with threats to its diplomats, even with assassinations, several times in recent years, mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean. From the point of view of the McGovern administration the important thing was to be compassionate and businesslike. Sargent Shriver reacted at once: he dispatched his Undersecretary for Management Bill Macomber with a small team of staffers on an Air Force flight to Cairo. In a brief private meeting President McGovern agreed entirely with Acting Director Felt from the FBI that it was a damnfool idea to let good men get shot out of a warped notion of national pride like the Israelis seemed to, and that the best thing to do was help the Sudanese keep these guys talking until they accepted something like safe conduct to Libya, or perhaps Egypt.

Macomber felt very strongly that there needed to be some fraction of give on the part of the Jordanians, to help things along and keep Noel, Moore, and Fritts out of imminent danger. When he pled that to Secretary Shriver, Shriver listened. There were communications to Amman, through the diplomatic mail and more directly; Macomber and several of his team paced the aisles on the way to Cairo eaten up with worry. In a show of Ivy League sangfroid, the trio of hostage Americans wrote letters to their wives given in trust to the somber Saudi ambassador. In Amman, not quite two and a half years out from the explosions and chaos and Syrian intervention that nearly toppled the Hashemite Kingdom, King Hussein claimed a breakdown in communications when the American ask for lenience came through.

Macomber’s team were full of energy and frantic improvisation: they ginned up a Quranically correct plea for mercy and charity to Egypt’s devout president Anwar Sadat among other feats. The West Wing counseled patience. In the end none of it was up to them. A coded message was sent through the Saudi embassy’s own telex system into which the PLO back office, whose catspaw Black September was, had tapped. As Bill Macomber debated in conference calls with the US embassies in Khartoum, Cairo, and Amman whether to stay put or fly ahead to Sudan, the fedayeen checked their watches for the time, ushered the three Americans down to the basement just after sunup of the second day, and shot them dead. Eight hours later they laid down their weapons and walked out with the Saudi ambassador’s family and staff unharmed, after a livid demand from Sudan’s president who believed the whole bloody mess was a setup to embarrass him before an upcoming Arab League conference. An ashen-faced Bill Macomber walked into the dust-blown embassy in Khartoum as staffers processed a blizzard of telexes, or broke down in tears, or both. King Hussein squared his chin and said nothing. And then home came the coffins three, draped in the flag, the first Americans to die in the line of the nation’s duty since the all too recent end in Vietnam.

But there was a trail. Black September and their masters kept their records off the books, kept them out of the usual paper trails, but could not set them apart from the hum and ether of a telecommunications age. That was where the National Security Agency, the United States’ signals intelligence service and, just perhaps, even more unsettlingly effective wiretappers than the KGB, stalked them, found them, and tracked them down. There had been a watch on such traffic since the late days of the Nixon presidency; now there was a priority cause. Within two days the NSA had verified trails from the Saudi telex — it didn’t hurt to read the sheikhs’ mail, either — back to the PLO’s headquarters by the coast of southern Lebanon. The question now was what that meant, what a new administration with a lot on its plate and a sudden furor that Americans were dead in another godforsaken place would do.

There was more. The NSA, true to its intelligence brief, was as concerned with what might happen as what had happened. As a result threat assessors at NSA headquarters at Fort Meade correlated the chatter out of south Lebanon and several known PLO safe houses abroad with coded diplomatic traffic from the Iraqi embassy at the United Nations. The link to Iraq was already on the list of probables; a shared dislike of Jordan kept Baghdad’s cables on the watch list. In this case, however, the codebreakers pieced together something more remarkable and far more urgent.

In the second week of March, Israel’s prime minister Golda Meir was scheduled to speak at the UN. In preparation for that, it seemed, a Black September field man named Khalid Al-Jawary had already set in place a pair of car bombs — two to make sure — along Fifth Avenue, timed to blow Meir’s small motorcade to kingdom come. In a fit of sweet reason word passed like lightning to the Federal Bureau of Investigation and from them to the NYPD, who lit out with deliberate speed to the places specified in the Iraqi cable.

Yet even before the national security state came to bear, the ambush was swept aside by the pure tectonic inertia of a big city’s civil servants. The towed cars were traced through the pink and yellow carbon paper of the appropriate offices. One detachment of NYPD bomb techs were treated to a cherry blossom of dirt and flame in a sprawling scrapyard on Staten Island just as they arrived on site. When reporters asked about the blast Police Plaza shrugged its collective shoulders and muttered something about those damn Puerto Rican separatists, or the chance of a mob hit botched. When NYPD turned to the FBI field office with more than academic interest in how the Fibbies knew where to look, the cops heard a familiar answer: don’t ask.

One terrorist attack abroad might turn out to be a bitter quirk of the present age; two, to the recently appointed Director of Central Intelligence Pete McCloskey, started to look too much like a campaign. He gathered the agencies and, when it was all typed out on paper, it was clear that together they knew who, and how, perhaps even why. The Palestinians wanted to strike at Jordan and Israel, of course, but why bring in the States? In part, the analysts proposed, because they wanted to test just how pro-Israel this new Democratic president was, whose party wanted a Jewish capital in Jerusalem and whose Congress liked lucrative arms sales to the Jewish state. They also wanted to see just what a president who set such great store in peacemaking would do. What we need to do now, said McCloskey bluntly on the phone with Gary Hart, is figure that the hell out.

What came of it, when George McGovern decided he needed to sit the principals down in the Oval Office two days out from the would-be car bombs — the CIA station chief in Athens had a whiff of Al-Jawary, or so McCloskey said — was that there were two options. Two roads in a wood and all that, as the President said while Doug Coulter took the official notes, but it’s a hell of a wood to be in.

The first option was plain enough: Tom Moorer with his cherubic face and Navy blues briefed it in. The USS Forrestal’s carrier battle group was already on scheduled maneuvers in the Eastern Mediterranean. Everybody already knew where the PLO’s operational headquarters was, the significant question was whether NSA and the National Reconnaissance Office could identify with confidence who happened to be there at a given time. It was a simple matter from there. Two pair of RA-5 Vigilante recon jets off the Forrestal, the biggest birds you could work from a carrier, had grid-marked the site in photographs already. On orders eight A-6s with a flight of F-4N Phantoms as fighter cover would depart the Forrestal’s deck, and come in from about six hundred miles out and just a few hundred feet off the water on final approach. Just before “Beginning Mean Nautical Twilight” — dawn to everyone else — the Intruders would launch a total of sixteen Walleye television-guided glide bombs that would flatten the whole damn compound and pin survivors under the rubble.

That was one way. It was, as Moorer together with his bosses the studied and patrician Cy Vance and Townsend Hoopes both pointed out, also a good way to end up with a new Middle Eastern war on your hands. Not just any old-fashioned war either, but riots across a region, bombs thrown at American legations and no uniformed army to shoot at in return, who knew how many American dual-nationals in Lebanon scooped up and kidnapped in some cave somewhere, or laid out dead along the Beirut Corniche to make a point. At the same time it would be a hell of a message. The powers these fedayeen had, as Paul Warnke pointed out with nods from McCloskey, were mobility and impunity. This was one case where the PLO had sacrificed that mobility. The question was whether decapitation would wither the threat or make it fragment like shrapnel.

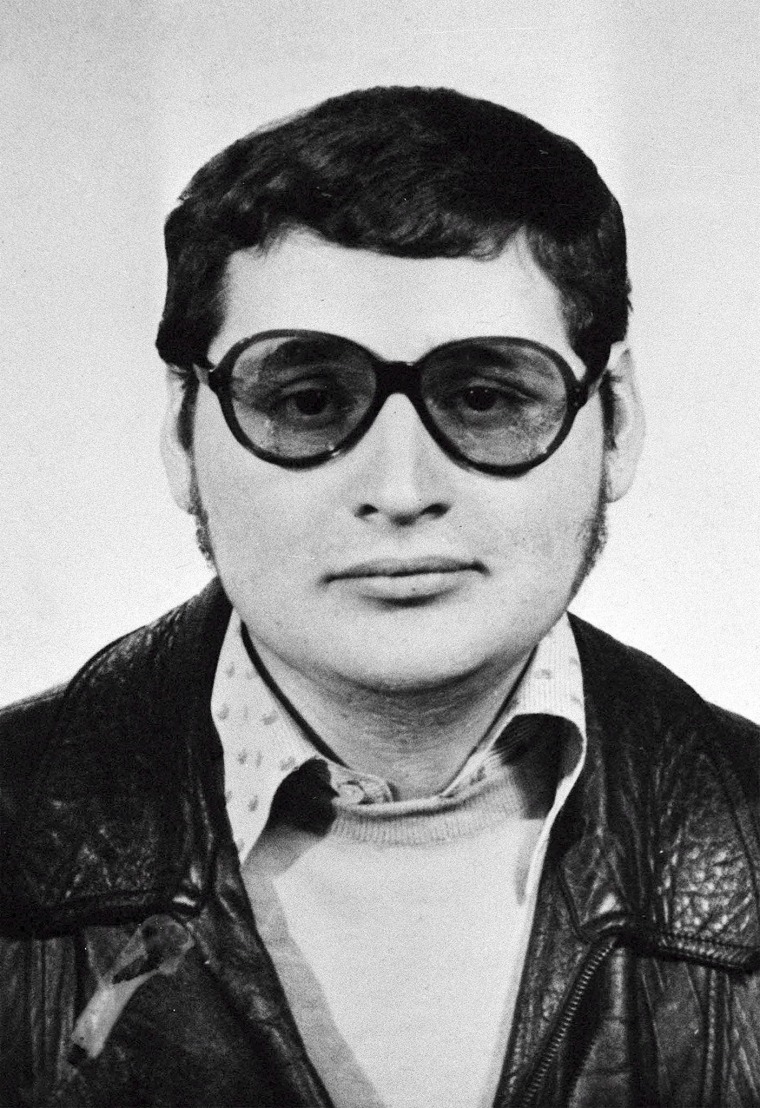

When Sarge Shriver stressed how good it would be to know more McCloskey pulled out a rumpled manila folder with a glossy black-and-white tacked on the front. Time for option two. The DCI minced no words: Ali Hassan Salameh, he said. They call him the Red Prince. Yasser Arafat’s chief of security, Mediterranean playboy, dedicated guerrilla in the late Sixties when the fedayeen were still poking the bear from the east bank of the River Jordan. Appeared to be tangled up with Black September directly, and certainly the Israelis wanted his scalp in connection with Munich. Langley had established contact several times in the last two years but without substantive results. As was his way, Salameh played coy. But they had a man — real all-American type from Pennsylvania named Ames, but he was really good at shoe leather work in the Levant — placed to reach out if there were orders, if there was a plan. There you were, McCloskey said with his usual bulldog Irishness. You could kill the bastards and maybe start a war, or you could talk to one particular bastard who’d maybe conspired to kill three Foreign Service men.

McGovern listened with his usual, flinty consideration. The pause as he did so began to fall into its own space, where some of his advisers wondered if this was another time where McGovern preferred to let things carry on, go their own way and look again when there seemed to be better chance to get things just so. As Tom Moorer settled back to write off the meeting and Paul Warnke moved forward to prompt an answer, McGovern spoke.

“I understand the reasons. Just yesterday I took some time with the families of these men and … I do understand it. It’s not that. We’ve done a lot of bombing for peace in the last ten years and it doesn’t seem to have gotten us anywhere. I don’t mean to foreclose anything but we just can’t afford to sidestep into another conflict when we haven’t thought that through. And we are going to have to start somewhere besides just Tel Aviv if there are ever going to be two sides talking to each other in the Middle East. So here’s what we’re going to do.

“Send this message. To the Iraqi mission in New York, send it there first, and tell them it’s for their friends in Lebanon. Message says, We just missed your call in Sudan. We did pick up the phone in New York, and we will listen for that line with interest in the future. We would like to speak to someone who knows us already about the situation in the region. We want to talk with anyone who can offer solutions. We do not want any more calls like the ones recently. People could get hurt that way. Pete, get that out please straightaway.”

The listeners caught the signal inside the noise again, heard from Fort Meade as the President’s words pinged from Manhattan to the Iraqi Foreign Ministry in Baghdad and from there to a pair of residential phone numbers in Beirut and a sprawling compound near Sidon. Half a week on a young runner for Fatah left a note with the hotel desk where an American business traveler named Ames was staying on Cyprus. Two days after that the broad-shouldered, golf shirted Company man sat back at a cafe table in ready conversation with the Red Prince. The lifer administrative secretaries at Langley collated the material under the codeword OLIVE TREE. So it was under Director McCloskey’s watchful and broadly approving eye that the United States found an in with the PLO. The day the two interlocutors broke bread in Cyprus a pair of US Navy Phantom jets off the Forrestal streaked in low over a tastefully decaying villa by the Lebanese coast, as their big twin engines strained against heavy bomb loads. Down in the villa Yasser Arafat told some excitable young aides to calm down and craned out a window to see. As it went over one of the jets dipped its wing. Just so you’d notice.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Old River Control, every foot of it — two hundred thousand tons of concrete and re-bar, the sluices and bars and revetments — spoke boldly of the ancient human need to spite God. From that point, that human hand thrown up against a rhythm thousands of years old, Louisiana spread out in all directions. Louisiana’s bayous, silt deposits, and wide, rich bottom land was the physical evidence of how it was formed. Every thousand years or so, a new channel made from deposits and winds and climate snared the Mississippi and pulled it in a new direction that built up Louisiana around it, then was snared again by a different path leaving a dank backwater behind. Now, if you gave nature a free hand, the Atchafalaya basin waited to snatch up the third-mightiest river in the world and pull it away from the long dogleg to New Orleans.

Trouble was, if that happened now a long river run of industrial and petrochemical plants, a string of cities small and large up to one of America’s greatest ports, and the whole artery of swift commerce from the inland United States down into the Gulf of Mexico, would be cut off and wiped away. It would be an economic catastrophe so great engineering experts said in hushed tones that it might swing not just the commercial health of the nation but the fate of the Cold War. That simply couldn’t happen; humanity, or at least the Army Corps of Engineers, needed to bar nature’s way. So they did, going into the 1960s, with the vast control structures at the Old River juncture, the chain on the door to keep the Mississippi steady and out of a fatal shift into the Atchafalaya.

For a decade Old River Control did its job in quiet. Despite the occasional hurricanes weather was relatively mild along the Gulf and conditions consistent. Then, from the autumn of 1972 into the spring of 1973, as the nation’s politics tumbled and fell then rose again in strange new ways, things changed on the Mississippi. On the far end of the same climate event that scoured Soviet wheat fields, heavy snow dumped down in the north of the Mississippi’s catchment basin, which was practically all of North America’s waterways, while it rained like hell down south. Boosted up in channels that had been both raised and narrowed by sediment, downpour and melt rushed south in the constricted space like the face of Creation’s waters.

The National Weather Service, the Farm Bureau, everyone who really cared about how the weather could change the country watched and tallied it up with growing dread. By the end of February the Department of the Interior had joined in. Jesse Unruh, its secretary who looked not so much as though he had been born as quarried, was California bred and Kansas born: he knew climate catastrophes when he saw them. Snippets started to head upriver to the Oval Office itself, where messengers nudged by Unruh and even by Treasury Secretary Galbraith could get in a word. President McGovern had spent his boyhood in sight of the Dust Bowl’s clouds and so payed attention. When they met on the National Parks budget McGovern quizzed Unruh. Mr. President, said the Interior Secretary, we’re watching the Ohio River. We have the Mississippi in the channels right now, even if there’s fifteen inches of rain south of St. Louis. But if the Ohio rises, God help us. McGovern nodded in cold contemplation.

As the days and weeks moved forward so did the crest of the tide. Cairo, Illinois, the northernmost point of the South or the southernmost point of the North depending what street you drove down, spent over three months in muddy water with the big river at flood stage. Memphis watched that great girder bridge across the Mississippi and held its breath against nine weeks of raging waters. Poorly reinforced levees south of St. Louis gave way and the thunderous force of water opened up a stain you could see from space cross the bottom land below the city, as the news cameras whirred and people slogged through corrupted floodwater the depth of a child’s pool while they braced buildings and laid in sandbags to hold back the climate’s judgment from real estate and infrastructure and livestock. All the while it roiled and grew, more and more millions of gallons of water per whatever unit of time you cared to throw at it, faster and faster as volume through a narrowed space obeyed the mathematical language of the universe.

There was work to do in the meanwhile and that was sure a damned mess, on that every senior member of the McGovern administration and every congressman who gave them a piece of their mind knew for sure. Parts of the problem, including the levees’ failure down in southern Missouri, lay at the feet of the Corps of Engineers and the control boards with which they interacted through the Executive Branch and Congress alike, a snare of committees and review panels that seemed to exist mostly to point out over and over what had gone wrong for the evening news to hear. Some of the administrative structure for processing such a disaster — claims for relief, repair of public housing down the often impoverished length of Big Muddy, temporary housing, municipal asks for federal aid or planning permission to do some localized flood control — all went through Housing and Urban Development, but the new HUD bureau handed the job was more a notion of Congress just yet than a properly staffed or funded agency. George Romney went down to Arkansas, towered over mayors and farmers as they swept the landscape with pointed hands and showed how folks who’d had very little now had nothing, and until House Appropriations ponied up a supplemental resolution could only tighten that lantern jaw of his in empathy.

As farms and elementary schools fought the germ-filled tides and the out-of-season mosquitoes and bad plumbing, Health and Human Services tried to step in too. There one of the questions was more … fundamental. Inspectors and nurses could be hurried down to the floodsites but HHS’s secretary, the learned and driven Andrew Young, a highly educated black man from the big city, was not a favored guest in floodstruck towns down a river that fed corn and cotton and plantations even in the present day.

By late March, as President McGovern emerged from the chilled trailers at Wounded Knee and late-night rounds of talks with Congress on the Demogrant and the Rehabilitation Act and the Endangered Species Act and that very FFRA, from a jet-lagged five day marathon in Western Europe, and whatever else circumstance saw fit to hurl his way, two things became clear. First, that the aid and recovery the federal government could provide up and down the Mississippi was a headless, convoluted mess, where people who had lost everything were now defeated again by conflicting claims papers with different agencies, by lack of coordination between departments, and in the incremental mire of work orders and process assessments that traveled like a cloud wherever the Corps of Engineers worked. Johnny Carson made mordant observations every few days, the television news droned on about the erosion of farmland and civic fabric, and that smarmy bastard Reagan out in sunny California kept telling that acrid joke that the worst words you could expect to hear were, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” After enough times that got under people’s skin around the West Wing.

As a practical matter something needed to be done. McGovern, leery as he often was of wading into departments and rearranging them, gave Phil Hart a chairmanship, asked in HUD and Agriculture and Interior and Charlie Bennett the Secretary of the Army (as representative of the Corps, and as a well-read environmentalist) to see what they could bang out. There are plain, clear needs here, said the President. Figure out how to meet them.

Another thing was even clearer and far more urgent. All the high water, all the swollen brown expanse down out of the Midwest past busted berms and through washed out shotgun-shack downs down towards the Delta, all that resolved itself on to a geographic point. That point was where the overgrown rage of the river passed the siren expanse of the Atchafalaya. There, millions of gallons of water beat on the structure of Old River Control like a hammer of judgment. The whole damn thing vibrated, shook so loud that everyone could hear, from wry Cajun site managers who managed the outflow valves even when their blood ran cold, to city-folk oglers who up and ran when they got close enough to see what it was really about, to local fishermen who plain couldn’t believe their ears and had a grand time saying so to those worn-faced men who came to work every morning just to see if the Mississippi would make a wreck of the works of men.

On both sides of the mighty walls, down so low you couldn’t see it, the whorling physics of the churn tore out holes and craters bigger than football fields, shook the great steel beams down in the loam where they tried to hold fast as nature laughed, rattled the fabric of the whole thing so that, like the joke ‘Nam vets made about the Huey helicopters, Old River Control was five thousand fragments damming in close formation. That couldn’t go on forever. Frank Mankiewicz talked to Charlie Bennett who talked to the chief of the Corps of Engineers. Bill Clinton over at Ag’s Rural Development office churned out position papers on what the floods had done to farmers along the length of the river, and what it could do in different scenarios at the point of decision, namely Louisiana.

At the start of April President McGovern himself got on the phone with the Corps’ division chief for the Mississippi basin, Maj. Gen. Charles Noble. Noble was a stolid career sapper, used to the conflicting demands of interest groups in his region — farmers, fishermen, industry, politicians twisted like pretzels to satisfy those opposed interests in search of votes. He was cautious but determined, and decidedly cagey about what to do next. He “yes, sir”ed with the best of them, and spoke of the big project he already had underway, to airdrop and bulldoze in heavy earth to help channel water out faster and further away from Old River Control’s fruitlessly open gates. Noble had already asked to federalize the 225th Engineering Group of the Louisiana National Guard and their heavy movers to speed it up, which McGovern approved with a nod of the head. But that didn’t answer the question. The President knew in his gut the high water was on a precipice. He huddled his people.

How do we cope with this? McGovern asked. Phil and his group will get us on top of the administrative side, if we can just get some dry weather in Illinois and the Ohio River Valley. The problem is Louisiana, yes? The grim heads in the Oval Office nodded. The Chief of the Corps of Engineers went through the numbers. Water levels had been higher in some other flood events but the rate of flow, especially as the emptied basins of North America rushed through Louisiana, was at the highest level Old River Control could handle. McGovern did not like riding that out. He trusted everyone would do their jobs but he knew nature’s grim capacity. Can we do something more, he asked.

Gary Hart nodded and together with Jesse Unruh laid out a plat map of most of Louisiana. Hart’s rangy finger stabbed at the point: Morganza, he said. No one in the structure of decision-making has opened the Morganza Spillway yet. It’s the safety valve for overflow into the Atchafalaya, about thirty miles down from Old River. We get it open and we can relieve pressure on Old River Control before it gives way. Save the barrier, save the industrial belt down to New Orleans. Unruh and the chief of the Corps gave due diligence on the downside. Morgan City’s flooded already, this will make that exponentially worse. It will change the geography and the chemistry of the wetlands downstream from the flood flow. But it keeps the river where it is, Hart repeated. Unruh looked at McGovern with grave eyes and nodded.

Bill Clinton, present on Agriculture’s behalf, spoke up. Wait a minute, he said. Wait a minute. We have a few thousand farmers, mostly soybean farmers, downrange of Morganza. They have pushed hard on this because they’re ruined if we open Morganza. So are the fishermen. Every bit of that is a threat to Governor Edwards’ political future and it’s going to hurt downticket Democrats like hell. It will also be a hell of a job to get those people back on their feet after. Not just down past Morganza directly, there’s Morgan City as you all observed already, there’s the whole south of the state. Clinton with his byzantine memory cathedral of a mind ran the numbers and the connections like a jackrabbit. There was a reason the Corps had soft-footed the Morganza question. Clinton summed up: it’s like a doctor who can save the mother or the child. We don’t even know if that will save Old River or not because we can’t get close enough in present conditions to make a sounding.

Unruh and Frank Mankiewicz talked some more, and George Romney’s rumbling tones went over the scale of what would happen to Morgan City if they moved ahead. McGovern listened, shoulders perched. He tilted his head a little to one side. Then he straightened up and spoke: we’re going to open Morganza, he said. Not just to steady the flowat Old River, but enough to bring it down. We can’t lose New Orleans, or the inland waterway, or the levees upriver if the Ohio piles on. Not if we never even tried. The secretaries and undersecretaries and fixers and officials nodded and started to move. I’ll go down there, McGovern added. Frank, you remember that commercial because it was your idea, right? Mankiewicz cocked an eyebrow on his effortlessly agile face. McGovern added, I meant what I said to those factory workers that this job demands you do what you have to for the good of the county, and that you tell the people the truth about why. All those folks down below Morganza ought to get an answer from their president. I want George — he nodded towards Secretary Romney — and Bill there — a tilt towards Assistant Secretary Clinton — with me. Surely we can get a helicopter from New Orleans to Morgan City? Gary Hart said, the Marines should have no problem with that. McGovern nodded and told everyone to get to work.

So down they went. Down first the weighty metal gates at Morganza, first thirty to trial and steady the flow, then forty, then by the end of that first day sixty of one hundred twenty-five, nearly half its capacity that raced down the swamplands and gorged over farms and power stations and the Morgan City levees. From the sky it was hard to tell the flood-wrecked trees and the hundreds, maybe thousands, of dead deer from one another. The Atchafalaya crested over the bridge at Morgan City and earnest, bespectacled reporters in helicopters talked about it over the rotors’ low roar in living rooms around the country. The troubles to the north began to ease as late spring brought clearer skies. The flow eased down by Old River, as girders still shook in a steady hum but the Mississippi stopped short of grinding the “project-level” structure into pumice. The navigation channel swelled but stayed its course down to New Orleans.

Down too went the President and his men in a big green CH-53 that landed in a mud-soaked park near the parish courthouse in Morgan City. With them came the state’s freshman senator, J. Bennett Johnston, a son of Shreveport come downstate to offer solace and federal money to the swamp Cajuns. He was the lone Louisianan with the Washington men. Governor Edwin Edwards stayed put in Baton Rouge. Ever since the days of Huey Long if not before the governorship of Louisiana was a tribunal for the public, in practice open for business to the highest corporate bidder but on every election stump in the state a bulwark and a beacon for the little man. The Long boys had imbued it with a civic magic; to have grim-faced suits from D.C. swoop in and change the face of the Atchafalaya Basin with federal orders, that was to have that spark of godhood stripped from you in front of everybody. You needed to keep as far off the consequences as you could. McGovern, who liked Edwards better than the other folks who might gun after Edwards’ job, respected that fact.

Back up in the U.S. Capitol Hale Boggs, at least six fingers down the bottle when he started in, wagged his finger and thundered before the press about federal high-handedness and the common people of Acadia fit to make Huey proud. It was all part of the show, but it tended to escape the earnest and occupied president down on the Gulf that reporters could adapt Boggs’ parochial theater-piece for narratives of their own. In the privacy of his Senate office Huey’s natural boy Russell, master of the Senate Finance Committee and wary foe of McGovern’s grand strategy on taxes, placed a call down to McGovern’s suite in New Orleans at just five cents a minute as Russell’s daddy had guaranteed. When McGovern answered, Long said that whatever came of Morgan City, the president had spared “the German coast” (called that because of all the industrial plants) and New Orleans itself. The men who called the shots would be courteous enough to remember.

Down in Morgan City it was as if two different presidents had been there, with two very different outcomes. It all depended who you asked. In outline the story read the same: McGovern and his men set down a little after 11:00 that morning, met for over half an hour with civic and parish leaders and business executives. Then he stood on the courthouse steps and delivered a statement for about seven or eight minutes, then walked through the crowd and talked with people, then toured the edges of the flood in waders himself while George Romney, Bennett Johnston, Bill Clinton, and the rest worked the room with townsfolk and displaced farmers. McGovern was flat and uninspiring as he pestered the mayors and sheriffs who briefed him on the damage, or he was cool and attentive and asked pertinent questions. He droned about how these people’s pain was for the good of the country, or he laid himself open and accountable to the people of these parishes for his decision to act at their expense. There were protest placards here and there, or there was polite applause when he came up to speak. One lady in horn-rimmed glasses lectured him about the ungodliness of his government and the divine punishment of the flood, or a couple of old Cajun fishermen leveled with McGovern and shook hands because he had the guts to face them about what he’d done — in this case both were clearly true. McGovern was a small figure, clumsy and almost literally at sea as he plodded through the brown water in his waders, or he walked purposefully through the places that suffered the most shoulder to shoulder with ordinary people. Views diverged.

As he followed the followers again — his moonlighting during the campaign had turned into a book contract and now a watching brief for Rolling Stone — Tim Crouse summed up perhaps his most powerful conclusion about the McGovern administration, about its effect on American life. “It was down in Louisiana that the thought came to me at last,” he wrote for the May issue. “Almost no one could actually report on President McGovern, at least not by the official rules of objective journalism. This was because, for nearly all professional reporters, what McGovern did and said was not “news” in the strict sense since none of its substance was new. To the press everything he did was a foregone conclusion, for good or ill. Everything filtered into one frame or the other. The people who could just take an act of this White House, work from facts, and then reason towards the administration’s logic or to possible outcomes, were few and far between. For everyone else those were just details in a tale already told. The outcome would be what they thought it would be, because George McGovern was who they thought he was. Not even Dick Nixon had wrecked American journalism so thoroughly, and President McGovern hadn’t even tried.”

The weeks moved on like the water, down into a bigger sea. President McGovern had just come back to Washington from a frosty Baton Rouge confab with Edwin Edwards, while George Romney mapped out infrastructure like a good Republican and young Clinton charmed older Cajun ladies like an evangelist because he felt their pain. Phil Hart’s committee on disaster management — Frank Mankiewicz gently suggested they find a different subject title before the press had some fun — came back with the outline of a Federal Disaster Response Agency that would wed emergency response to natural calamities with civil defense, against which both bureaucratic fiefs and congressional budget hawks howled. Gary Hart wore through his shoe leather back and forth to the Capitol as the president used Stuart Symington to proxy a continuing resolution so HUD could pay to house the displaced along the Mississippi, and another so the Corps of Engineers could pay day labor for a few weeks’ work bagging and mounding the banks back on to the Mississippi.

Then word came Harry Truman too had slipped away to join Lyndon and the dead whose church had widened to bring in Greeks and Koreans and Hiroshimans and more. Back to the Rotunda went a black-clad George McGovern, again made by the weight of his office to say thoughtful words about a man whose foreign policy had nearly clipped McGovern’s then-tender roots in the Democratic Party, a fact remarked on by several columnists who had varied points to make. If there was a new day afoot in Washington, Gary Hart observed to Doug Coulter, it sure spent a lot of its time burying the old one.