GRANULARITY! ORG CHARTS! My nerd heart is loving all this. Great to see you back @Yes! Seeing a trend of Big is Beautiful among the Departments will probably lead to some byzantine bureaucratic warfare and infighting (especially in the Pentagon). Wonder if that's really more efficient than splitting everything up or not; have to wait and see I guess. If Education isn't spun off, is Sanford retconned to be a Deputy Secretary then? Can't wait to hear more about Jimmy's plans for nuclear and renewable energy and hopefully keep those CA oilmen out of there. As always, awesome job.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

McGoverning

- Thread starter Yes

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

McGoverning Bonus Content: The Big Damn McGovernomics Explainer McGoverning Bonus Content: Fearsome Opponent - John Doar, Dick Nixon, and Prosecuting a (Former) President McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, People and Process McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, A Strategy of Arms McGoverning Bonus Content: Moment of Historiographical and Thematic Clarity McGoverning Bonus Content: A Strategy of Arms II McGoverning Bonus Content: On Cartographers McGoverning Bonus Content: A Cambridge Consensus?Glad to see more in thread content and my goodness you went deep with the org charts.

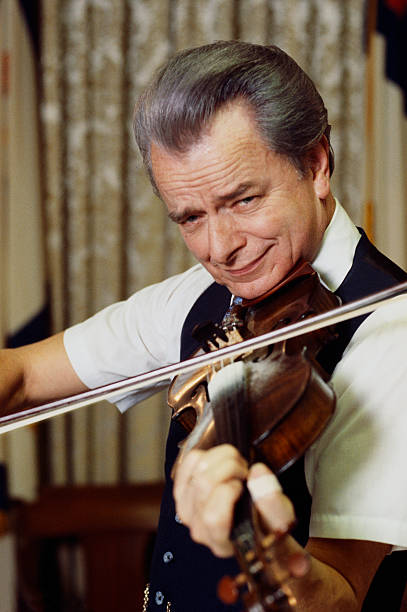

Well played in finding the creepiest photo of Bob Byrd possible for that..

Hi.

GRANULARITY! ORG CHARTS! My nerd heart is loving all this. Great to see you back @Yes! Seeing a trend of Big is Beautiful among the Departments will probably lead to some byzantine bureaucratic warfare and infighting (especially in the Pentagon). Wonder if that's really more efficient than splitting everything up or not; have to wait and see I guess. If Education isn't spun off, is Sanford retconned to be a Deputy Secretary then? Can't wait to hear more about Jimmy's plans for nuclear and renewable energy and hopefully keep those CA oilmen out of there. As always, awesome job.

I am happy when I can warm the hearts of nerds, being a rather large one myself (in all senses, being 6'2" and built kind of like a retired linebacker - I did play tight end as a teen - and also the, "you mean I can do a deep dive into a subject unto relentlessly pointless levels of detail? ROCK THE FUCK ON" senses both.) Yes that's a retcon for Terry, though it does make him one of the most powerful DepSecs in DC at a time when that bureau within HEW expands rapidly so he can kind of set his seal on how it operates. We will see a bit more of JIMMEH in his National Grid Ride or Die role coming up so that is indeed something to look forward to. Thank you.

IT RETURNS

This is probably one of the rare TLs that runs slower than actual time. (Shows the level of detail put into it.)

I laugh that much because I can take that one squarely on the chin - it's entirely right, and funny 'cause it's true. Thanks for the kind words about detail.

Well played in finding the creepiest photo of Bob Byrd possible for that.

Yeah, I mean that's ... yeah. Just, yeah. Every photo I dig up of Robert Byrd in his alternate life as a Seventies fiddler has a deeply curated creep factor.

Actually, what I want is someone even nerdier than me to write a series of stories where Bob Byrd and his fiddle are the actual inspiration for "The Devil Went Down to Georgia" and in his spare time when the Senate's in recess, he fights supernatural crime. That would be a kind of pointless Skippy the Alien Space Bat cool I could really get behind.

Hard at it getting there on the West Wing With Sideburns and Macrame post. A number of folks to cover, but it's coming along. Might be tomorrow depending on a family obligation late afternoon but I'm pushing for tonight if I can make it.

Onward to 1975. Maybe you can make a post covering monthly events for 1975 and 1973, like you did for 1974 ITTL. Should be very helpful in acquainting newcomers to McGoverning.I am happy when I can warm the hearts of nerds, being a rather large one myself (in all senses, being 6'2" and built kind of like a retired linebacker - I did play tight end as a teen - and also the, "you mean I can do a deep dive into a subject unto relentlessly pointless levels of detail? ROCK THE FUCK ON" senses both.) Yes that's a retcon for Terry, though it does make him one of the most powerful DepSecs in DC at a time when that bureau within HEW expands rapidly so he can kind of set his seal on how it operates. We will see a bit more of JIMMEH in his National Grid Ride or Die role coming up so that is indeed something to look forward to. Thank you.

I laugh that much because I can take that one squarely on the chin - it's entirely right, and funny 'cause it's true. Thanks for the kind words about detail.

Yeah, I mean that's ... yeah. Just, yeah. Every photo I dig up of Robert Byrd in his alternate life as a Seventies fiddler has a deeply curated creep factor.

Actually, what I want is someone even nerdier than me to write a series of stories where Bob Byrd and his fiddle are the actual inspiration for "The Devil Went Down to Georgia" and in his spare time when the Senate's in recess, he fights supernatural crime. That would be a kind of pointless Skippy the Alien Space Bat cool I could really get behind.

Hard at it getting there on the West Wing With Sideburns and Macrame post. A number of folks to cover, but it's coming along. Might be tomorrow depending on a family obligation late afternoon but I'm pushing for tonight if I can make it.

Last edited:

McGoverning Bonus Content: The West Wing, Sideburns and Macrame Edition

I blame Aaron Sorkin. Disclosure: that’s something I do not infrequently, since I belong to a generational cohort that both has cause to blame Aaron Sorkin for a lot of things and also gains practical and cultural advantage by doing so.

We’ll leave the long-form on that aside. Let’s just say that the kinda-sorta wildly inaccurate picture of who matters in what ways in an administration’s West Wing (occasionally hailed at the time for verité by the same sort of hacks who grossly inflated their own importance when they acted as advisors to the show) maybe needs a corrective.

So we’ll skip right past that. Let’s look at the real thing, specifically the real thing as it existed/operated in the early Seventies, as our brave band of scoobies took office. We have three good reasons to do that.

Thing One: It’s an excellent opportunity, through a specific example, to look at how a West Wing operation, aka The Executive Office of the President of the United States, could/would function around that period in time.

Thing Two: Because it gives us a good view of the real cast of decisive personalities in that Executive Office of the President. Humans make history: personalities have a big influence on how an administration creates and then does policy.

Thing Three: It’s the best way to get a look at what we really can call the Sociology of McGovernment, which is a crucial and kinda fascinating subject.

So. Let’s start.

We will back into it from that sociological angle. That is, fundamentally and as you’d expect, a political sociology. Over the decades a lot of political scientists, journalists, and historians have described George McGovern’s insurgent nomination campaign and the political fractures it generated in the Democratic Party a contest between “reformers” and “regulars.” It is of course more complicated than that, but that’s not a bad place to start: a contest between outsiders, upstarts, and innovators on one side, and folks who had well-established careers within the established Democratic Party order (sometimes back to FDR, certainly from Truman through Johnson) on the other. The most dramatic, heightened contrast there is often posed as the conflict between Our George and AFL-CIO boss George Meany, but that’s just the most polarized example.

I’d suggest that there are in fact three overlapping categories here that have valence, and we should note them down up front. They are

- Reformers, largely as described though we’ll get into the granular stuff as we go

- Regulars, likewise, and then also

- Retreads, which is an unkind way to put it but alliterative – this special but significant population in McGovernment consists of folks who had personal, significant roles in either or both of Jack Kennedy’s administration and Bobby Kennedy’s 1968 campaign

The other thing we’ll find, as we go along, is that – warts and all – the McGovern team was quite capable of building a West Wing operation of talented people who could take on the tasks before them. If there are faults or complications or internal conflicts or anything else like that, well, that’s in common with every single other administration there ever was, IOTL or in any ATL you’d care to propose. Let’s start in the neighborhood of the top, and at the center.

White House Chief of Staff

I

deserve to be

with somebody as fly as

me

somebody this

fly

- Silk Sonic, 2021

Hands off, ladies, he’s TTL’s.

In the McGNU it can be said fairly of Gary Warren Hart (née Hartpence) that he was a significant, perhaps even daring, architect of the unparalleled activist ground game built around George McGovern’s primary and presidential campaigns; that he worked at that like a driven man; that he adapted rapidly, fluently, and perhaps even intensely to the professional company of major political players especially in the liberal-to-left wing of the Democratic Party (but not just there: IOTL Barry Goldwater called then-senator Gary Hart one of the most honest and moral men he’d ever met, which tells you perhaps more than you wanted to know about Hart’s ability to suck to up to people with power and Barry Senior’s skill level at judging character); that he stepped into the administrative – and very, very much the media – role of “George McGovern’s whiz kid” like a man born to the purple.

Now there’s a Richard Ben Cramer sentence for you.

Several other things are also true. That Hart was really among a whole crew of whiz kids of genuinely remarkable political talent: like the greatest strategist among them, Rick Stearns; incomparable primary ground-game pit bosses like Joe Grandmaison and Gene Pokorny – GEEEEEEENE!! WHO LOVES YOU BABY?!?; ITTL political natural, media maven, and gateway drug for Hart Gary’s entree to the celebrity lifestyle, Warren Beatty; and seemingly endless numbers of precinct-level McGovernite entrepreneurs of diverse ages and backgrounds. A bit like Miles Davis in his quintet years, Gary Hart had real talent but he stood on the shoulders of giants in order to look like one himself. Also Hart was a lot better at organizing state and national-level organizations than he was at managing smaller offices closer at hand where he knew everyone – those were often a real mishegas if he was ostensibly in charge. He was determined to show off his smarts but sometimes undermined himself in the doing. He traded shamelessly on George Himself’s loyalty to a McGovernite of the first hour, which to be fair Gary Hart was. And Gary was never afraid to throw a proper snit when he felt someone had edged in on his authority or his bureaucratic patch within the campaign.

Those fact patterns, that tale, tells you a lot on the road in about what Gary Hart as White House Chief of Staff might be like. To that, we should add one more crucial point of data that one might already have teased from prior details but if not, we’ll spell it out here.

That data point is this. Based on all the evidence accreted over a nearly sixty year public life, it seems fairly clear that there are two things – one in his private realm, one in his public – that Gary Hart quite desperately wanted to be. Both certainly emerged out of the environment of his deeply awkward, dysfunctional, shame-driven upbringing, but probably also owe a real degree of something to the way Gary Hart’s wired. So, nature and nurture, both. The private thing is that he desperately wanted to be a man-of-destiny ladykiller. The public one is that he desperately wanted to be a Man of Ideas.

By some real measure he was more successful at the former than the latter, though even that was convoluted and sometimes tawdry. But Hart really, really, really wanted to be a Man of Ideas. The trouble there, ultimately, was twofold. First, that he was, in some meaningful degree, rather shallow when it came to it, and so too was his command of ideas and gaming out concepts and pursuit of chains of argument. He was bright, and driven, and given to fierce study of all sorts of subjects so that he could become that very Man of Ideas. But his takes were most often a mile wide and a few inches deep. His campaign book for his 1984 presidential effort IOTL, A New Democracy: A Democratic Vision for America in the 1980s and Beyond (see, even his idea of a grand, sweeping title falls kinda flat), is a few hundred pages of warm oatmeal, a run-on chain of platitudes. It’s Big Concepts that other people had come up with already that impressed him with his own cleverness for agreeing with them, that smarter people had already thought through into the detail and nuance of their fractals, occasionally disproving or offering alternatives to what he puts out as grand pronouncements. It’s very Gary of him. And it’s why, when Fritz Mondale asked Gary Hart “where’s the beef?”, that punch landed.

Second, despite the fact he was a reasonably accomplished lawyer and some of the time a pretty competent political campaigner, he wasn’t what you’d call intellectually agile. Which is not necessarily the best characteristic in a White House Chief of Staff, though it’s an acceptable one if you’re another powerful person in the administration hierarchy who thinks the Chief of Staff was poorly chosen and needs to be managed in order to prevent difficulties.

You may ask yourself (HI TALKING HEADS) what does Hart Gary’s actual job look like? Let’s borrow from the wiki (which borrowed from a book about White House Chiefs of Staff) and do a quick run down on major actual or potential elements

- Selecting senior White House staffers and supervising their offices’ activities (as we’ve seen and will see, efforts have been made to vest the first part of that in other authorities, though Gary will probably do what he can to satisfy his desire to do the second part of it)

- Managing and designing the overall structure of the White House staff system (again it’s a mix of the McGovernment transition team setting that in stone before Gary starts the job, to Gary surfing on top of the deeds of others so he can take credit)

- Control the flow of people through the Oval Office (you can believe he will get ya-yas from this – as we’ll see three jobs down, though, things other than people can flow through the Oval Office)

- Manage the flow of information to and decisions from the Resolute Desk (more the latter than the former – there’s a determined effort to vest the first part with the job three down from this one)

- Directing, managing, and overseeing all policy development (this is the part of the job Gary Hart really wants, and where he vests a lot of his effort, though even there there are other people who play essential roles)

- Protecting the political interests of the president (as we’ll see, a lot of this in McGovernment is vested with the Counselor to the President, which will come up when we reach FRANK)

- Negotiating legislation and appropriating funds with United States Congress leaders, Cabinet secretaries, and extra-governmental political groups to implement the president’s agenda (the other part of the job Gary loves best, his opportunity to suck up to/prove his worth with the power elite)

- Advise on any and usually various issues set by the president (again a part on which he’s dead keen)

As we go along, we’ll have a chance to see position by position how the presidential transition wise heads go about boxing Gary in to a manageable, defined space in order to contain what they see as potential negative effects of his central position in the Executive Office structure. Beyond that their hope is that like many Chiefs of Staff before him, the job will wear him out in time and he’ll search for fresh pastures. But that might underestimate the sheer ferocious drive of the Nazarene kid with the gawky smile …

Deputy White House Chief of Staff

(Yes that’s a photo from late in his life. But really, if you blow up some of the grainy, small images of him in his Vietnam days, a guy then in his twenties, it’s the same face, here just with white hair and a few extra lines. Hell he was even down to a widow’s peak in the Sixties – hairline’s not too different either.)

We bring up Douglas Eliot Coulter in this prosopography of the West Wing for two reasons. First, because he’s an example of “footnote history” at its finest – people obscure IOTL who, but for a chance here or there, would be much better known. Second, because he’s an important player in how everyone who is not Gary Hart in the McGovern administration’s West Wing manages the fact that Gary Hart is White House Chief of Staff.

If he were not one of the whiz-kid reformers – and he is – Doug Coulter would make a perfect retread, because he’s a child of their dominant culture. A minor scion of the Eastern establishment, in part Mayflower-descended (partly a Brewster by way of his paternal grandmother), Coulter was born in DC while his father had a cushy gig there, though the Coulters considered the inherited family manse in New Hampshire, where mostly they summered (belonging as they did to the culture that can use “summer” as a verb), as the family home. Doug was valedictorian of St. Alban’s School, then on to cozy Harvard College at the larger Harvard University, where he won a prize as the college’s outstanding sophomore in his year. He finished slowly, taking time off to travel as far as Europe and Madagascar, the latter doing volunteer work, then picked up an MBA at Harvard Business School.

After that, his life path took what we could call a very him turn. As the eldest of four kids in a hallowed WASP family, Doug had a deep sense of civic obligation, wedded to a taste for adventure. He didn’t believe he should avoid a war that poor hillbilly kids and people of color couldn’t, so he volunteered for officer candidate school – yes, you guessed, he was top of his class, and thus whisked off to the “Q Course,” e.g. the qualifying training for US Army Special Forces.

He then spent all of 1967 in-country with 5th Special Forces Group on Project DELTA (no not that one, one of the “Greek-letter” deep recon teams that beat the bounds of the Ho Chi Minh trail.) His immediate superior, another young officer named Captain Hugh Shelton – you know that name already or you should wiki it right now – reflected then (and in the acknowledgments section of his own memoir decades later) that Coulter was one of the two or three best officers of any rank he (Shelton) met in two yearlong tours in Southeast Asia.

Doug Coulter wasn’t a religious man but he inherited a strong cultural strain of left-hand Puritanism from his ancestors: he was deeply disillusioned by what he saw as the failure of political, civic, and moral vision in Vietnam, and much of American postwar culture generally. So he became an earnest and effective field organizer for the McGovern campaign, when it came time for that. (For an adventurous, curious, and ambitious guy Coulter also had that keen Puritan sense of personal failings, not just others’ but his own, that he carried with him through a lifetime. It was allied to a sense of “must do better” that made him strive to, but it’s an important personal characteristic.)

IOTL, of course, George lost. IOTL, Coulter went on to be a key Midwest organizer for the Carter campaign, for which he was awarded a post on a new regulatory board that governed US copyrights. He taught for a while in the Eighties, then saw another opportunity when the Berlin Wall fell. Coulter was an eager and adventurous world traveler, a lifelong francophile, and good at languages. He taught himself both Russian and Guanghua (Mandarin), and spent what turned into decades shuttling between Moscow and Beijing in what those cultures would call the “loyal liberal” role. Disillusioned with his own country’s downward arc from Vietnam through Nixon and Reagan, he played the missionary’s role trying to teach loyal-liberal types in Russia and China how to compete in the global economy and pull their societies in a more open direction. He married a Russian wife, had three kids of his own (still summered in New Hampshire though), and eventually died quietly at eighty-one.

Here, though? Here things are different. Here Doug Coulter enters the ranks of the administration’s new hires at not quite thirty-three, one of a cadre of late-twenties to thirtysomething whiz kids who helped make the improbable upset happen. More than that, as the McGovern presidential team sifts through resumes, Doug Coulter has an outstanding resume in the eyes of some powerful people who have a very specific concern.

The core of George McGovern’s presidential transition team – a fearsome foursome of Clark Clifford, Frank Mankiewicz, Ted Sorensen, and Larry O’Brien – was, to be direct, pissed off that George Himself wanted to reward Gary Hart’s loyalty and enterprise by making that same Gary Hart Chief of Staff. As we mentioned above, this resulted in an elaborate strategy designed to box Hart in, more of which we’ll see in operation as we go along. (Spoiler: pay special attention to the next three jobs right after this one.) But a box alone wasn’t enough: they also wanted Hart to have a minder.

Enter Doug Coulter, I say in parentheses. For the transition bigwigs, Coulter’s both the right sort of people and has a stellar resume for his age (including a pretty high-level security clearance from his Army days, readily renewable.) The transition team decides it would be a very good idea if Hart Gary (as opposed to Hart Phil) had someone of Coulter’s gifts and capacity shadowing him (Hart) one step behind and to the right any time he (Hart) walks into a room. Also someone (Coulter, now) with an administrative role that would make him an efficient cleaner and restorer after any messes that Hart happened to make. And there you have the Deputy Chief of Staff.

There are two specific facts about Doug Coulter that lend dramatic tension and character/plot-arc interest to the working relationship between Gary Hart and his deputy. The first is, broadly, what we might call Coulter’s keen and somewhat weary eye for sin – in many ways the original Anglo-Saxon usage, in which the root of our modern word referred to an arrow that missed its mark. Doug Coulter had an intuitive sense of human frailty and fallibility, from real ill intent to simply missing the mark, a sense that dogged him through life though mostly he managed it.

The other significant fact is that Doug Coulter is demonstrably more intelligent than Gary Hart. That’s not at all to say that Hart’s just some knuckle-dragging goon. But Doug Coulter is a good deal more intellectually agile, able to think much better laterally and further down multiple detailed logic chains from an original proposition, than Hart is. Between them any semi-conscious sense Hart has of that makes for a source of tension. For the brighter deputy who tidies up after a less clever and shall we say morally erratic boss, it can be a source of frustration. And – Doug Coulter would be the first to tell you this – it can be a temptation.

Counselor to the President

Now we get to Frank. Everybody loves Frank; that’s kind of his superpower. It makes him a mainspring of the McGovern White House: everybody loves Frank, so he can tether the whole operation together – even when other individual folk quarrel and feud with one another – through the common denominator of Frank-love. Also, so long as he holds some sort of demonstrably senior position within the organization, everyone feels like there’s at least one safe pair of hands close enough to the top that things will be ok (Gary Hart feels that too but that’s purely self-directed, even as he mostly gets along with Frank when they each stay in their own lane.) As a result of all that Frank can in effect write his own ticket as a player in the West Wing hierarchy, so he does.

There have been Counselors to the President before Frank, either by that title or a similar one. Sometimes there were multiple at once, sometimes they had greater or lesser importance. ITTL, in the McGNU, it is very specifically through Frank Mankiewicz’s personal and working relationship with President George McGovern that a singular Counselor to the President granted “cabinet rank” becomes the president’s consigliere.

What that especially means, in the ecosystem of McGovernment’s West Wing, is that Frank is very much The Politics Guy. Now, everyone in that environment thinks they’re The Politics Guy/Gal to some degree, that’s the lingua franca and the shared reality. Certainly Gary Hart, among others, likes to chime in on matters political. But when it comes to the classical smoke-filled-room, handshake, back-slapping, horse trading, optics for the voting blocs, etc., sort of stuff, what they mean by “it’s politics” or “look at the politics of the thing,” that is where Frank is The Politics Guy. That’s his central role as personal adviser, very much in keeping with a consigliere’s brief.

Also, that’s a very interesting role for Frank to take on because, in many ways, when you look at the political sociology of McGovernment, Frank is a rather interesting character. He likes democratization on principle. He grew up in a properly Leftist American Jewish household in Hollywood, in a mostly like-minded milieu (though he seems to have gotten on fine with a few prominent Hollywood conservatives, just not the one who went and made himself governor.) He has a sentimental fondness for left-of-center Latin American governments, on the somewhat pragmatic principle that they seemed more likely to take an interest in the welfare of their nations’ poor majorities. He was part of an abortive opening to Castro IOTL’s mid-Seventies (encouraged by Kissinger) and wrote a book about the trip.

At the same time, though, in a whole lot of other ways, Frank is really something of a Regular. He goes back a bit in Democratic politics. He’s worked among the biggest wheels in the party. He understands how the game is really played most of the time. He’s a bit fusty about a variety of things – indeed IOTL he and his strange-bedfellows reactionary buddy Lyn Nofziger (as Frank put it, nearly the only thing they agreed on was that they liked each other personally) played a key role sinking the effort to convert the US to the metric system. In practice, Frank could readily be called “a Regular with Reformist characteristics.” He does have those reformist characteristics, but he wants to play, and succeed, by big boys’ rules in the big-tent scrum of the Democratic Party. He’d be perfectly happy to tell the idealistic young longhairs (and at least some of the uppity women) to take a hike so that McGovernism gets taken seriously enough by the ward bosses and union chiefs and long-term Congressional backbenchers, etc., that it can become a permanent force in the party. He sees McGovernism, especially, as an acceptable successor to what the late martyred Bobby was trying to build (though, in practice, there are some important differences, among them the fact that George clearly really meant it.) So in that sense Frank is a sociological triptych – Reformer, Regular, and Retread all in one.

The Politics Guy thing, though, that’s key. In some ways it carries over from the campaign: Hart Gary does operational stuff, Frank finesses the grandees. But given time and the opportunity to entrench oneself into a role, there’s a very dialectical relationship that then builds up between those two personalities so close to George. A less emotionally private – even remote – man than George might really get pulled at from different directions by it. In practice we’ll have to see where that dialectic takes things.

Staff Secretary to the President

Meet the most important job in the White House that most people have never heard of.

Per wiki, the White House Staff Secretary “is a position in the White House Office responsible for managing paper flow to the President and circulating documents among senior staff for comment.” That really undersells it. The second ever, and one of the greatest, Staff Secretaries, then-Colonel Andrew Goodpaster, more or less invented how the postwar White House processed information and made himself, by management of sensitive documents and acting as editor for what and how key information reached Dwight Eisenhower, Ike’s real national security adviser (though Ike employed others at the same time. Goodpaster was also the longest-serving Staff Secretary IOTL, on the job for seven years.) Properly managed, the Staff Secretary’s office is the nerve center of the White House – a Chief of Staff might manage who goes in and out of the Oval Office, but in this data-rich era a gifted Staff Secretary takes a POTUS faced with too much information and not enough time and designs what information that POTUS receives plus how POTUS gets to use it. For a POTUS who’s a trained academic historian like George McGovern, who loves him some primary sources, that role then is practically the keys to the kingdom.

So. The transition brains trust makes sure it goes to not only the safest but also perhaps the most engaging set of hands they could come up with. Richard Goodwin was himself a whiz kid of the Retreads: a lower-middle-class Jewish scholarship kid to Tufts and Harvard Law, Goodwin clerked for Felix Frankfurter and became a junior speechwriter for Jack Kennedy on the eve of his presidential run. That made Goodwin, twenty-nine when JFK took office, one of the youngest of Kennedy’s own whiz kids, the “New Frontiersmen” – Ted Sorensen, Fred Dutton, Ken O’Donnell, Ralph Dungan, Goodwin himself, and Harris Wofford, all of them thirty-seven or younger when Jack started work.

Though Goodwin might have looked a bit like a clean shaven rank-and-file of Tolkien’s dwarves – or, as one columnist put it during Camelot, “a hungover Italian journalist” – he was possessed of deep, ready, electric charm, a renaissance man and raconteur. Besides speechwriting Goodwin became a utility infielder for the Kennedy and early Johnson administrations, the general of the generalists. He helped design a whole new program of inter-American (as in the American continents) economic and cultural relations. When Nasser built the Aswan High Dam, Goodwin mobilized international aid to relocate and thereby save the ancient temple of Abu Simbel and other classical Egyptian relics. He hung out at inter-American political conferences with Che Guevara. If it had dash to it and sounded a bit too novelistic to be true, Goodwin did it. At least until he wearied of Lyndon’s Vietnam policy, then taught at places like Wesleyan and MIT, before he managed Gene McCarthy’s New Hampshire operation in 1968 (when Bobby entered the race, Goodwin dutifully changed horses.)

He was out of the political loop in 1972 for bitter personal reasons – his first wife, Sandra Leverant, died that year. ITTL, Frank comes to him during the transition and says it’ll do him (Goodwin) good to have work to do, something to concentrate on, to fight for, that they’re getting the band back together to staff George’s administration, that the lost brothers would tell Goodwin it’s the right thing to do. And Richard Goodwin, to his lifelong credit, was nothing if not a sentimental fool, so he signs right on.

It’s good timing. Goodwin’s no dotard himself, just edging into his early forties at the time, still full of much of the old ebullience despite his long hard walk with grief, still the master generalist with the fairy dust of Camelot about him. And really Staff Secretary – curator and crafter of President McGovern’s knowledge base about absolutely everything, mastermind of the White House nerve center – is one of the jobs for which he’s best suited.

Also, he’s inherited the position at a time when it pulled a fair amount of additional bureaucratic weight within the Executive Office. After administrative changes to the Staff Secretary’s role during the Nixon administration, it took on additional tasks with personnel management, White House finances, access to the White House Mess (dining room for senior staff) plus the limousine fleet, facilities management, and oversight of the Executive Clerk and Visitors Office. It’s a whole handful.

It also shades in on multiple fronts on the role and bureaucratic potency of the Chief of Staff. This is part of that “box strategy” designed to contain any difficulties with Gary Hart. It also creates what we could call “narrative tea” for other reasons. For starters, Dick Goodwin already is the sort of person who Gary Hart aspires to be. Add to that this crucial and broad-ranging position, and Goodwin alternately becomes someone Hart wants to emulate and gain approval from, but also a rival for the power and influence Hart would like to aggregate to himself. Seems like time and familiarity will brew up a big ol’ pot there.

White House Cabinet Secretary

We’re not quite done with whiz kids yet. Born the same year as Gary Hart and Les Thurow (more on Les below), Morris Dees was the McGovern campaign’s direct mail small-donor fundraising genius. In the McGNU that’s even more true as he provides the continuous financial lubrication to get the computer-assisted guerrilla ground game over the finish line to victory.

Direct mail was Dees’ original gig, almost straight out of law school, and in the long run (some would say to the SPLC’s eventual cost) it was one of his most successful vocations. He sold up his original operation during the late 1960s for $1 million in that day’s money, because of its presumed market value. Even IOTL, his work for the McGovern campaign was the most successful small-donor political operation to date. As I say, even more so IMyTL.

So, come time for the presidential transition, Dees has an in for a solid reward from McGovernment. Possibly a substantive gig at DoJ, or his pick from a grab-bag of minor ambassadorships. But Morris Dees wants a job close to the center of power, where he can do well (advancing his own political connections and career prospects, both with the nascent SPLC and in the direct mail game more broadly) by doing good. Sure enough, there’s one of those available to him.

The White House Cabinet Secretary does what the job says on the label: coordinates the Executive Office’s administrative and working relationship with the Cabinet departments and similar federal agencies on a day-to-day basis. It’s the real sausage-making bureaucratic grunt work side of those relationships, yet also an exercise in understanding the players in that environment and keeping them on good terms with the White House. A fiercely quick study with empathetic Southern charm, Dees knows how to keep that bread buttered on the correct side. It also keeps him on a first-name, they-owe-me-a-favor basis with Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries, Undersecretaries, agency heads, public affairs officers, inspectors general, and other main players in the executive branch at all times and on all fronts. It’s a Rolodex wonderland for someone of ambition and if there’s something Morris Dees does not lack, it’s ambition. And unlike the perpetually quasi-dorky Hart Gary, Dees can lace it all with a genteel and genuinely understanding smile.

National Security Adviser

Let’s get on to some policy bigwigs – not just bigwigs, but folks who sit at nerve centers of their own for the creation and conduct of McGovernment policy. We’ll start with one of the two most important folks in that category who we can find in the West Wing. He occupies that position for two reasons that make total sense in the sociology of McGovernment: he’s a significant Retread who’s also a full-blooded Reformer, and he brings to his relationship with President McGovern himself a combination of uncommon personal friendship and political loyalty of just the sort that George liked to reward.

Paul Warnke grew up in smokestack-town Massachusetts – I could listen to his Eastern Establishment drawl for hours – where his father managed a shoe factory and from which he went on to Yale (other than a handful of Harvard folk, distinguished Yalies are a major demographic within the upper ranks of McGovernment), then served as a combatant Coast Guardsman during the war (on a subchaser in the Atlantic, a Landing Ship Tank in the Pacific). After he graduated Columbia Law he got a coveted spot with Dean Acheson’s pet firm, Covington & Burling, and shot up the ranks to partner by the mid-Fifties.

While he was not part of the Camelot crew, Warnke became General Counsel at the Pentagon under LBJ, then took on a crucial policy-level bureau as Assistant Secretary for International Security Affairs. He became a key member of an informal interagency task force set up on Johnson’s behalf by Nicholas Katzenbach, that looked at how to extricate the US from Southeast Asia, and played such a key role convincing Clark Clifford to pursue deescalation and the Paris Talks when Clifford became SecDef that, when Nixon entered office, Warnke became a partner in Clifford’s law firm.

Alongside Kennedy administration international law expert Abram Chayes, Warnke became one of the two foreign policy/national security advisers closest to George Himself during the McGovern presidential campaign. Here in the McGNU George would’ve liked it if Warnke could’ve become Secretary of Defense. But the transition team – notably Warnke’s other good friend and patron, Clark Clifford – recognized that Warnke would’ve faced furious, vituperative resistance from Senate hawks who saw Warnke as “the guy who convinced Johnson to cut and run.” So, instead, building on their authentic personal friendship, Warnke becomes now-President McGovern’s national security adviser.

Paul Warnke’s a fascinating and deeply engaging guy. You get the sense that you wouldn’t want to cross him or get his dander up, but the rest of the time he’s engaging (if just slightly self-satisfied, but it comes across as faintly arrogant self-assurance rather than dickishness), fearsomely smart, warm, cheerfully salty, and a heartfelt Reformer on the crucial Cold War issue of arms control. Really it would be hard for George to have a more capable national security adviser, or one more temperamentally suited to McGovernment. Warnke’s no peacenik – one might describe him as a dove with sharp claws – but he’s a very intelligent and fearsomely well-read (also well-argued) advocate for a comprehensive program of nuclear arms control, well ahead of conventional wisdom’s curve. And, ITTL, one of the reasons CART succeeds (at least so far, up to the point of drafting and signing the treaty itself, before the Senate takes up ratification) is because Warnke and Special Envoy to the Rambouillet Talks Clark Clifford work so well together.

There might be some temptation, in an administration like this one, for Warnke to trade on his special access and special relationship with POTUS to become the sort of be-all end-all policy formulator and implementer that Henry Kissinger became with Nixon, and IOTL Zbig Brzezinski tried to become with Carter. But, as we’ll see in the policy post upcoming, that’s dissipated by two key factors. One is Warnke’s own preference for a collegial decisionmaking process – provided it’s one where he can still aim his stingingly well-reasoned reformist barbs at conventional wisdom. The other is that the “big four” principals of McGovernment’s foreign and national security policy process – Warnke, Secretary of State Sargent Shriver (SARGE!!!), Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance, and Director of Central Intelligence Pete McCloskey, joined sometimes depending on the issue by SecPeace Don Fraser or SecTreas Ken Galbraith – genuinely get on with one another like old friends, to a degree rare among presidential administrations.

One thing that is very much bureaucratically and administratively true, in terms of outsized influence for Paul Warnke, is that he collaborates effectively with Dick Goodwin about how paper flow on foreign policy and national security issues is sifted, edited, and provided to the Resolute Desk for George Himself’s consumption. That’s not the sort of thing that would make for witty banter on early-Aughts NBC – though if any two men could raise it to that level it’d be Paul Warnke and Dick Goodwin – but it’s an essential element of how the McGovern West Wing actually runs.

Deputy National Security Adviser

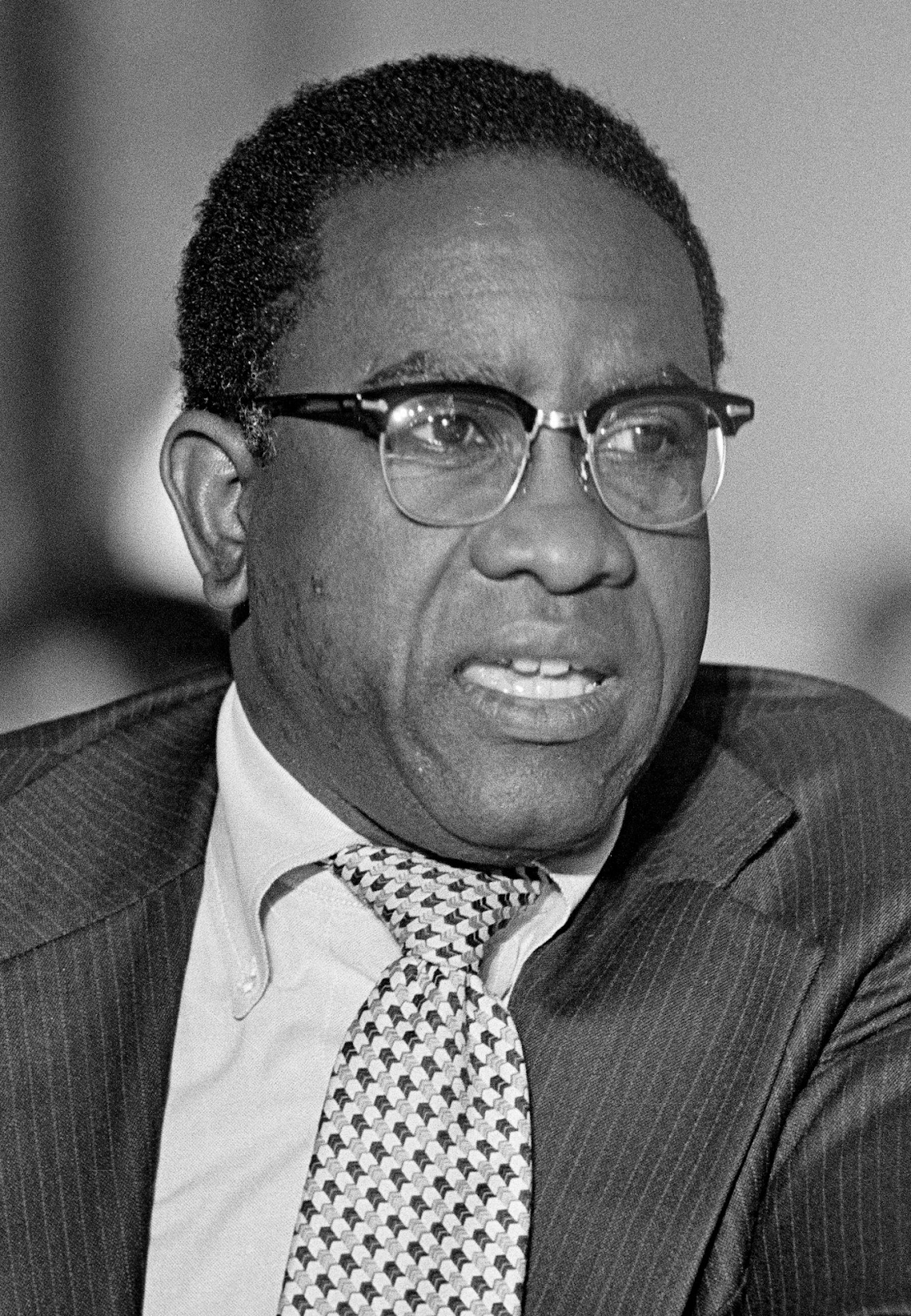

(I’ll say, parenthetically and up front here, that this period-accurate photo of Morton Halperin from the mid-Seventies looks a whole awful lot like a shorter version of my father at the exact same point in time. It’s a bit uncanny.)

Unlike the earlier mention of Doug Coulter, I don’t bring up Paul Warnke’s deputy here purely for his own sake, though Morton Halperin is a fascinating character and I’ll say why briefly. In this case, Halperin stands in for the small but powerful brains trust Warnke puts together on the National Security Council staff, folks key to the creation of a thematically well-reasoned and coherent McGovernment policy approach to foreign affairs and national security. (They do that alongside others too – Abram Chayes at Policy Planning in the State Department, the good DepPeace folk at the Arms Control & Disarmament Agency, John Holum at DoD, etc. – but Warnke’s NSC staff plays an outsized role.)

So, Morton Halperin. Like Dick Goodwin another bright Jewish scholarship kid from the boroughs, Halperin picked up a BA in international relations from Columbia at twenty then shot on through his MA and PhD at Yale by the time he was twenty-four. After both lecturing and think-tank work at Harvard, still in his late twenties, Halperin became a special assistant with International Security Affairs at DoD and soon after Paul Warnke’s direct deputy for policy, planning, and arms control for over two years.

Here’s where that gets so interesting it’s meta. While in that job Halperin supervised the team, led by Leslie Gelb, that compiled and created the Pentagon Papers. When news of the “secret” war in Cambodia linked in 1969, and a handful of years later the Pentagon Papers themselves, the Nixon crew suspected Halperin of a role. His name went on Nixon’s Enemies List and the Nixonians tapped Halperin’s phones, aggressively and illegally, for several years, but found no evidence of wrongdoing.

Beyond that, though: when he left DoD during Nixon’s first year in office, Halperin took a post with the Brookings Institution. His presence there, along with several other key former Johnson administration folk, and the possibility they held secret papers on more Vietnam shenanigans especially the “X File” on the Chennault Affair (actually with Walt Rostow in Texas), led directly to Chuck Colson’s plan to firebomb Brookings. Let’s chew on that for a bit.

Halperin’s the senior member of a small but highly select stable of National Security Council staffers who make up Warnke’s own team of whiz kids. The prominent members of that circle include

- Halperin himself

- Anthony Lake, whiz kid of national security policy during the Kennedy, Johnson, and early Nixon administrations, on topics from South Vietnam to SALT, until he resigned over the invasion of Cambodia (IOTL he’d go on to be Bill Clinton’s first-term national security adviser)

- Walter Slocombe, talented “white shoe” lawyer and Oxford-trained Soviet politics expert, who became a key NSC staffer during the initial SALT talks before he jumped ship to work for the McGovern campaign (IOTL a key Carter admin SALT II player)

- William Hyland, a Nixon holdover but of the old school who would work for any responsible administration as a public servant and another SALT savant especially good at working the big-department bureaucracies like State and Defense on arms control

- Strobe Talbott, dashing young correspondent, Sovietologist/Kremlinologist, and McGovern campaign staffer

- Robert Sherman, always spotted round the halls with his crutch due to a malformed leg, young international-relations gun and arms control autodidact who boostrapped his way up the campaign staff with smart policy papers (IOTL he played a key role as a congressional staffer in trying to ban space-based offensive weapons)

Director, Office of Management & Budget

(He’s facing away here, but this 1979 shot of Les in conference at the Sloan School of Management at MIT really lets you see the Thurow-fro in the full sunlit glory of its youth.)

If you thought we were quite done with whiz kids, we’re not. Time to cross paths with the West Wing’s big policy whiz kid, Oxford-and-Harvard-educated economist and MIT maven Lester Thurow. Thurow’s an interesting guy in his own right and more than that, in process and policy terms, he runs the biggest shop in the Executive Office of the President (in terms of personnel and budget lines), absolutely key to making McGovernment function – if we riff on a movie title – everywhere all at once.

We’ll move from office to man. The Office of Management & Budget is a keystone in the operation of the executive branch. I’ll just quote the wiki here for the short version of its sheer scope.

OMB prepares the president’s budget proposal to Congress and supervises the administration of the executive branch agencies. It evaluates the effectiveness of agency programs, policies, and procedures, assesses competing funding demands among agencies, and sets funding priorities. OMB ensures that agency reports, rules, testimony, and proposed legislation are consistent with the president’s budget and administration policies.

OMB also oversees and coordinates the administration’s procurement, financial management, information, and regulatory policies. In each of these areas, OMB’s role is to help improve administrative management, develop better performance measures and coordinating mechanisms, and reduce unnecessary burdens on the public.

Out of breath yet? For an administration (McGovernment) especially concerned to streamline and coordinate federal policy and administration, manage the budget closely (more in the policy post), and make sure everyone’s on the same page so reform efforts have the desired effect, this is an essential gig. So who takes charge of it?

Roughly the same age as Gary Hart and Morris Dees, Les Thurow is a Big Sky kid from a mining town in Montana, where the local mining company invested in what we’d today call the STEM elements of the local school system. From early one Les went at the theoretical side of those subjects, got a scholarship to Williams, then went on to Bailliol College, Oxford (MA in politics, philosophy, and economics) and Harvard (econ PhD). After that he took up soonish with the Sloan School of Management at MIT, a bit closer to the river. That puts him firmly in the Bostonian Nexus of McGovernment’s Justice League of Liberal Economists.

A 1989 (OTL) piece in The Atlantic, by a subsequently-famous science writer, called Thurow “The Man With All the Answers.” This was in part a dig – at Thurow’s energetic self-assurance that he understood how all of it fit together and what should be done – but also a mix of hope and awe at the thought that there was an outside chance Thurow actually might. Thurow’s comprehensive view of the economy, and his Reformer’s vision of a very different relationship between government and industry than the typical American approach, when combined with the policy implementation power of OMB, makes young Les one of the three or four most significant individual actors in McGovernomics (see more in that post when we get there.) He also guards rather jealously OMB’s outsized role in executive branch regulation and implementation through the yearly budget process.

United States Trade Representative

Meet the Regulars’ Regular. I don’t include Larry O’Brien here so much for his job as United States Trade Representative – we can give that role a mention but briefly – it’s really his Regularity that rates a short consideration.

The Office of US Trade Representative functions a bit like an Arms Control & Disarmament Agency for the global economy – it’s a coordinating entity and centralized negotiating arm that pulls together the many different departments and agencies involved in foreign trade negotiations, while the Trade Representative acts as whole-of-government representative during actual, specific trade talks. If you’re a left-curious reformist administration that just got elected during a chaotic political year rife with uncertainties, that’s a good job for a Regular – the optics alone are worth a small upwards bump or two on the Dow Jones.

Beyond that, though O’Brien is part of what you could almost call a Regulars College of Cardinals, bound up with the big AFL-CIO unions (especially the less “political” ones that backed George Meany) and a variety of “Catholic ethnic” political machines. Despite that he’d made his name running “statewide” campaigns, first for Jack Kennedy’s senate seat, then for Kennedy, Johnson, and Humphrey in succession at the national level. But he neutered Gene McCarthy’s delegate effort at Chicago in ‘68, scotched efforts to discuss – and critique – Humphrey’s Vietnam record in floor debates, then did all he could to rig the 1972 convention in the Regulars’ favor against the already extant, McGovern-Fraser Commission based, reformers as early as 1971.

But Larry’s also a complex character, in a complex situation. Here in the McGNU, O’Brien prosecutes the political case on Brookingsgate with as much vigor and as many resources as he did with Watergate IOTL. Also he’s in a delicate position – when he failed to find a way to let the Anybody But McGovern forces in the back door at the convention, he lost a lot of the political capital and good will he had with the big, old-line forces in the party, especially the Meany wing of the labor movement. His effort to both rein in the McGoverners and hold together the party in the face of Nixon’s criminality and Wallace’s burn-it-down insurgency means that he personally loses friends on both right and left inside the party.

His place in the machinery of McGovernment’s West Wing, then, is a sort of dual-facing normalization. On one hand, it serves as part of the process designed to normalize McGovernment in the eyes of key Regular gatekeepers and, for quasi-Regulars like Frank, to mend enough fences that the Reformers can get their feet under them enough to remain a viable force in the party. On the other hand, taking on that role of Regular gatekeeper inside the McGovernment tent offers O’Brien the chance to re-normalize himself among fellow Regulars, to say he’s always had their interests at heart, he’s just trying to make the unruly Democratic family function so it can govern in place of a criminal gang.

All of which is clever, as it goes. But there are plenty of folks in each factional camp with long memories about Larry. In fact, the next person on this list might like to have words with him sometime about Miami ‘72.

Director, Office of Policy Development

We’ll start this section with a pro tip about a case where the internet scores a win on open-source primary materials. Thanks to Utah State University’s Digital Commons, you can read the full .pdf version of Jean Westwood’s aptly titled “political autobiography” (with brief bits about the rest of her life front and back, it’s really about her political career in the Sixties and Seventies), Madame Chair. Here, have a link

https://veteranfeministsofamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Madame-Chair-Jean-Westwood-.pdf

Rather like George, Jean Westwood was a Westerner from a then-obscure state. A Utahn whose family went back to the early days of the state, the college-educated Westwood was a reformist LDS liberal who married a gentile (non-LDS in this case, as a Jewish dentist I once knew once said, “Salt Lake City is the only place I’ve ever been a gentile”), then became an entrepreneurial – and quite successful – mink farmer (you read that right) in Utah’s high country. Back when there was a Utah Democratic Party worth the name that won statewide offices, she joined its liberal wing and rapidly worked her way up the state organization with grit and skill until she became the state’s female Democratic National Committee member. She was involved with the nascent reform movement as early as 1968 on the road in to the McGovern-Fraser committee, then took on a key role at the top rank of the McGovern presidential campaign.

Connected with a few other sources that interweave with and complement it, Madame Chair tells us several valuable things

- She was as much, if not more, responsible for the specific organizational model and culture of the grassroots McGovern army as Gary Hart – borne out by the fact that it really did resemble (her idea) the way the LDS Church organizes its missionary operations

- Throughout the campaign even after she’d been elevated to DNC chair McGovern’s key field bosses, especially the top-level ones like Gene Pokorny and Joe Grandmaison, saw her as the architect of the ground game and bemoaned the fact she couldn’t return to run it rather than manage party-wide electoral matters

- She – as the floor boss, chief parliamentarian, and vote counter – together with Rick Stearns, the two of them, ran the parliamentary operation at the Miami convention that got the campaign back their full California slate and secured the nomination

- The senior guys (Gary, Frank, George) knew her value, complimented her often – Gary’s idle flattery, George’s heartfelt, Frank’s probably a mix of things – and elevated her to DNC chair, but often left her working in obscurity and, when the December ‘72 fight came against Bob Strauss for her to keep the DNC chair, it was the hesitance and sometimes desertion of McGovernites – when folks like Ed Muskie and even Richard Daley had decided to back her against the Connallyite Texan Strauss – that did her in (George was then largely AWOL during the depression he fell into for some months after the landslide)

The Director of the Office of Policy Development, essentially, runs the McGovern West Wing’s domestic policy shop. And in this we’ve seen her at times, and will see more of her both in future chapters and in rewrites. She’s an excellent manager, too, something not all of the mostly-male bureau bosses in McGovernment are, and never quits when she has a goal in sight. It makes her, together with Phil Hart, the two essential McGoverners in the creation and passage of MECA (the Medicare Expansion and Consolidation Act of 1974), and she’s the unsung hero of several other major policy fights, and wins.

The question, then, is just how long she’s ready to keep winning the day in obscurity for the administration. She believes in the principles, and the goal, so that even beyond personal loyalties keeps her engaged. But it’s not always easy to be the skilled, dutiful one who gets it done when other folks run around taking credit, or offer congratulations not always backed by substantive support.

Director, Office of Public Liaison

“Anne always loved the spotlight.”

Into that short sentence in her memoir, Jean Westwood packed a cargo hold worth of both admiration and distaste. One thing we can say, whatever our personal views about its significance, as a factual matter that’s demonstrably true. Throughout her long political career Anne Wexler both sought out public roles and leveraged them to advantage – whether that was more to the advantage of her candidates and clients or to herself could vary, but really that’s true for all flacks.

What made all that possible, to start, was Wexler’s own combination of genuine skill and fierce ambition. Like Jean Westwood, Wexler experienced an early-midlife full throttle shift from private life (where she was a self-described “Jewish princess” doctor’s wife) into the political arena. And she was sufficiently good at it that she shot up the Connecticut state party’s structure to manage her first United States Senate campaign within five years. (Her guy lost, but she ended up divorcing the doctor and marrying him.) Two years after that she was a principal senior campaign staffer for the Muskie campaign. When that crashed and burned she quickly shifted gears to the McGovern effort and became a key rep on party committees and a voter registration maven of the first order.

The Office of Public Liaison is a natural place for Wexler, where she can leverage her love of the spotlight and natural facility at working with political, civic, and business movers and shakers. The job is ostensibly that of “chief lobbyist-general for the administration’s agenda” with the world beyond Congress. For McGovernment, another key component is the practical side of open government – bringing in key interest groups from the public, state and local governments, corporations, and the rest to understand what McGovernment’s up to and how it operates, how it’s ready and willing to listen to the public. All things considered she’s more comfortable with the lobbyist part, but the administration wants a public face for open government and she’s happy to be it. Spotlight, indeed.

White House Communications Director

An Irishman and a poet, in roughly equal measure – that’s Dick Dougherty. (Also he was a novelist and a playwright, so “man of letters” is really about right.) IOTL he wrote the most intelligent, thoughtful, and heartfelt after-action memoir to emerge in the immediate wake of OTL’s McGovern campaign, Goodbye, Mr. Christian, one that gives to my view one of the most (possibly the most) accurate understandings of George Himself during that time. (Disclosure: I own a treasured, dog-eared copy in hardcover. Thanks, Powell’s City of Books!) A longtime and fairly distinguished police-and-city beat newspaper correspondent for several major papers of the day and for a while an NYPD public affairs officer, Dougherty had the most street cred with the “Boys on the Bus” of any McGoverner save Frank Mankiewicz (though Frank at times kinda-sorta undermined Dougherty’s position as press man in favor of Frank’s inexperienced protege Kirby Jones.)

Here in the McGNU Dick is the campaign’s comms guy right through the X File and all the harrows of October, and is really rather ready to be exhausted and hang up his spurs thereafter. But when Clark Clifford sits you down at a hotel bar and explains why you really need to take over Herb Klein’s Nixonian novelty the White House Office of Communications – while veteran and cheerfully salty fellow Irishman and Muskie flack Mark Shields acts as Press Secretary – you tend to listen to what Clark Clifford says to you because, well, you like working ever again. So – during the reasonable amount of time that Frank Mankiewicz will let him do it for himself – Dougherty becomes coordinator of McGovernment’s media operation. That he’s an old school press guy who’ll be straight with even the stringers is one of his most useful qualities. And I’m sure the book he writes about TTL’s experience – and he will surely write about it – will put Goodbye, Mr. Christian in the shade.

Well that’s it for this installment. I mean there are other fascinating folks in the Executive Office. We could talk about distinguished feminist lawyer (and co-author of a groundbreaking law review article on “Jane Crow” systems of legal discrimination by sex) Mary Eastwood who’s Director of Intergovernmental Relations, or why having Gordon Weil be the White House Personnel Secretary (in charge of vetting hundreds, if not thousands, of administration personnel appointments) is a very mixed bag. Or what job title they give George’s energetic, sentimental young body man Jeff Smith while his wife Amanda acts as Chief of Staff for the First Lady. But then we’d be here all week. There will be cameos, I’m sure. But now we need to move on to making the sausage – policy’s up next.

Last edited:

For a little bit of Pancho-and-Lefty McGovernment national security policy action, please just enjoy this delightful CSPAN video of George Himself and Paul Warnke talking, both one after the other then together during Q&A, to Johns Hopkins undergrads about arms control in 1985. I sometimes watch it just to relax because I'm a disturbed individual.

www.c-span.org

www.c-span.org

Arms Control: Strategy and Diplomacy

Senator George McGovern and Ambassador Paul Warnke talked about strategic arms control negotiations and they answered audience questions.

McGoverning Bonus Content: Sideburns and Macrame Addendum

Good people! We missed our White House Counsel!

That's entirely my fault. Trying to juggle too many things in too many facets of life at once. But. Let's step in there and add to the mix.

White House Counsel

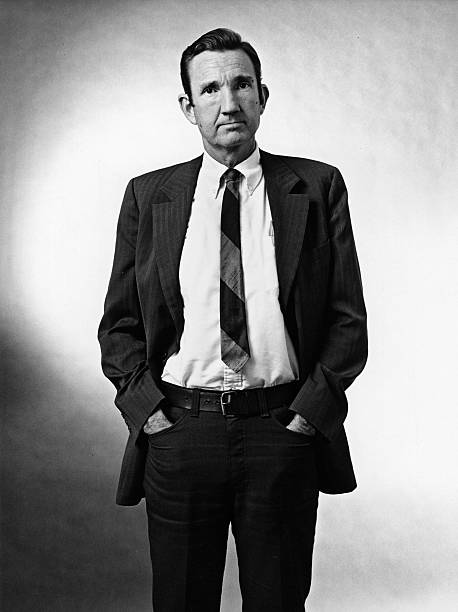

Giving big Jimmy Dale Gilmore energy - too look at, Clark was

one of the most Texan public figures of his era (and this is him

in 1974 still wearing his Sixties suit and tie because does he

give a crap about fashion? I think not)

The White House Counsel is a president's top personal legal adviser. We should stop and clarify "personal" there because the distinction matters. The White House Counsel is the personal legal adviser to the President in the sense of "the king's two bodies" - he advises the office-holder, really the presidency itself, not the human who holds the office in any private or personal capacity.

They cover a lot of ground: legal issues tied to legislation, ethics matters, financial disclosures, the legal difference between official and political activities, conflict-of-interest matters, the administrative/procedural management of presidential pardons, and a lot else. Notably, as we actually saw in a past chapter, the White House Counsel also acts as part of President McGovern's advisory conclave dealing with the prosecution of former president Richard Nixon - what charges to pursue, how to go about management of the legal strategy, negotiation towards a plea, etc.

Ramsey Clark might go in his own particular category in the sociology of McGovernment - a Retread Radical. Born to the legal purple (son of a former US Attorney General and SCOTUS judge, plus distinguished Texan legal types as grandfathers on both sides), Ramsey dropped out of high school to fight in World War II, then went to the University of Texas undergrad (HOOK 'EM) and picked up both an MA and a JD from the University of Chicago. He joined the family law firm in Texas, then became a New Frontiersman with the Kennedy administration where he worked his way up the Justice Department to Deputy AG 1965-67 and Attorney General the last two years of LBJ's full term. Clark was both Kennedy's and Johnson's frontline sonofabitch on civil rights enforcement, but enjoyed his time as AG less especially the prosecution of draft resisters, a process he privately found somewhere between personally distasteful and morally wrong.

Once he was out of government he taught at Howard University's law school and protested the war, going so far as to visit Hanoi in 1972, so he's a political hot potato entering McGovernment - good that he has one of those jobs in the presidential gift, rather than one dependent on Senate confirmation. But he's very much in line with the left-hand tenor of George's shop. And he has, besides his own "radical" progressive tendencies, an unimpeachably formidable legal background. Plus, perhaps, a yen for politics in his own right.

That's entirely my fault. Trying to juggle too many things in too many facets of life at once. But. Let's step in there and add to the mix.

White House Counsel

Giving big Jimmy Dale Gilmore energy - too look at, Clark was

one of the most Texan public figures of his era (and this is him

in 1974 still wearing his Sixties suit and tie because does he

give a crap about fashion? I think not)

The White House Counsel is a president's top personal legal adviser. We should stop and clarify "personal" there because the distinction matters. The White House Counsel is the personal legal adviser to the President in the sense of "the king's two bodies" - he advises the office-holder, really the presidency itself, not the human who holds the office in any private or personal capacity.

They cover a lot of ground: legal issues tied to legislation, ethics matters, financial disclosures, the legal difference between official and political activities, conflict-of-interest matters, the administrative/procedural management of presidential pardons, and a lot else. Notably, as we actually saw in a past chapter, the White House Counsel also acts as part of President McGovern's advisory conclave dealing with the prosecution of former president Richard Nixon - what charges to pursue, how to go about management of the legal strategy, negotiation towards a plea, etc.

Ramsey Clark might go in his own particular category in the sociology of McGovernment - a Retread Radical. Born to the legal purple (son of a former US Attorney General and SCOTUS judge, plus distinguished Texan legal types as grandfathers on both sides), Ramsey dropped out of high school to fight in World War II, then went to the University of Texas undergrad (HOOK 'EM) and picked up both an MA and a JD from the University of Chicago. He joined the family law firm in Texas, then became a New Frontiersman with the Kennedy administration where he worked his way up the Justice Department to Deputy AG 1965-67 and Attorney General the last two years of LBJ's full term. Clark was both Kennedy's and Johnson's frontline sonofabitch on civil rights enforcement, but enjoyed his time as AG less especially the prosecution of draft resisters, a process he privately found somewhere between personally distasteful and morally wrong.

Once he was out of government he taught at Howard University's law school and protested the war, going so far as to visit Hanoi in 1972, so he's a political hot potato entering McGovernment - good that he has one of those jobs in the presidential gift, rather than one dependent on Senate confirmation. But he's very much in line with the left-hand tenor of George's shop. And he has, besides his own "radical" progressive tendencies, an unimpeachably formidable legal background. Plus, perhaps, a yen for politics in his own right.

Last edited:

What a fantastic deep cut, @Yes, always magnificent to read the inner workings of the White House.

I really like the little snippets showing the internal relations between the old Kennedy people, the young guns, and the Regulars inside the administration. O'Brien pleasing nobody, Mankiewicz functioning as George's alter ego, and the whole section of foreign policy with Warnke, Halperin, Lake and others is delightful to analyze.

Oh Gary Hart, you irritating, brilliant fuckup. I still find it so funny that a good chunk of the rest of the staff has to band up to restrain his influence over McG. One must wonder what his future shall hold, though he'd be just as equally capable of burning out too quickly like Icarus.

Anyways, as always, thank you so much for your effort and wit. The McGoverning universe is such a richly deep world to focus onto, and these snippets are great examples of why. Take care, and we shall wait patiently for the quickly approaching Bicentennial.

I really like the little snippets showing the internal relations between the old Kennedy people, the young guns, and the Regulars inside the administration. O'Brien pleasing nobody, Mankiewicz functioning as George's alter ego, and the whole section of foreign policy with Warnke, Halperin, Lake and others is delightful to analyze.

Oh Gary Hart, you irritating, brilliant fuckup. I still find it so funny that a good chunk of the rest of the staff has to band up to restrain his influence over McG. One must wonder what his future shall hold, though he'd be just as equally capable of burning out too quickly like Icarus.

Anyways, as always, thank you so much for your effort and wit. The McGoverning universe is such a richly deep world to focus onto, and these snippets are great examples of why. Take care, and we shall wait patiently for the quickly approaching Bicentennial.

John Fredrick Parker

Donor

So next we're getting a glimpse into policy mechanics, followed by an explanation of the McGovern Administration's economic policy; that right? Then a quick post on Nixon's trial. After that -- considering it's been 52 28 months now, should us readers be expecting the story to return?

Last edited:

More like 30 months.So next we're getting a glimpse into policy mechanics, followed by an explanation of the McGovern Administration's economic policy; that right? Then a quick post on Nixon's trial. After that -- considering it's been 52 months now, should us readers be expecting the story to return?

WIP it good...

A quick update in case anyone is actually breathless with anticipation.

More bonus content to drop soon - this weekend, if I don't have an opportunity to push on through and get it done tomorrow.

Not the expected bit, actually: chewed over the policy feature a couple of different ways but it just didn't want to come together the way I'd hoped. So, I moved directly on to the Big Damn McGovernomics Explainer, which is now the bonus content soon to drop. It covers a variety of things:

- A tour d'horizon of McGovernomics' doctrinal and personnel components

- A short explainer on OTL's macroeconomic situation in the US (with some broader Western-world aspects) 1973-76

- A look, referenced from OTL's circumstances, at what McGovernomics does differently

- Attention to how McGovernomics acts as both a center of gravity and a fulcrum for a different and, at least ostensibly, more coordinated "First World" approach to economic issues during the presidential term George McGovern has won off of firebug Tex Colson

HI. Would you like to hear about price controls? I thought so.

In news that might excite some actual interest, one of the things a detour past the mooted policy post has done is free up both time and mental imagery to push ahead with actual narrative - no, really, that unicorn has been spotted and tracked to its favorite meadow. Stuff's afoot, and once McGovernomics is posted into the thread I may put a pause on the Nixon indictment memo in order to get on with that directly. Joe Strummer might've said that the future is unwritten, but the imagined past is getting there.

Right. I'll see folks back here in the next couple of days.

Last edited:

S

See you then!View attachment 821992

WIP it good...

A quick update in case anyone is actually breathless with anticipation.

View attachment 821994

More bonus content to drop soon - this weekend, if I don't have an opportunity to push on through and get it done tomorrow.

Not the expected bit, actually: chewed over the policy feature a couple of different ways but it just didn't want to come together the way I'd hoped. So, I moved directly on to the Big Damn McGovernomics Explainer, which is now the bonus content soon to drop. It covers a variety of things:

In the meanwhile, have this Tiger Beat of Mitchell, South Dakota picture of perhaps the most prominent McGovernomics-ist, Treasury Secretary John Kenneth Galbraith, conveniently taken in 1975 IOTL so it's TL-apposite.

- A tour d'horizon of McGovernomics' doctrinal and personnel components

- A short explainer on OTL's macroeconomic situation in the US (with some broader Western-world aspects) 1973-76

- A look, referenced from OTL's circumstances, at what McGovernomics does differently

- Attention to how McGovernomics acts as both a center of gravity and a fulcrum for a different and, at least ostensibly, more coordinated "First World" approach to economic issues during the presidential term George McGovern has won off of firebug Tex Colson

View attachment 821995

HI. Would you like to hear about price controls? I thought so.

In news that might excite some actual interest, one of the things a detour past the mooted policy post has done is free up both time and mental imagery to push ahead with actual narrative - no, really, that unicorn has been spotted and tracked to its favorite meadow. Stuff's afoot, and once McGovernomics is posted into the thread I may put a pause on the Nixon indictment memo in order to get on with that directly. Joe Strummer might've said that the future is unwritten, but the imagined past is getting there.

Right. I'll see folks back here in the next couple of days.

Galbraith looks like John Cassavetes in this picture. Who knows maybe John could play Galbraith on television or in a film while raising money for one of his masterpieces with Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk and Ben Gazzarra.View attachment 821995

HI. Would you like to hear about price controls? I thought so.

Attachments

That’s an excellent catch. I like that idea.Galbraith looks like John Cassavetes in this picture. Who knows maybe John could play Galbraith on television or in a film while raising money for one of his masterpieces with Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk and Ben Gazzarra.

Ramsey Clark as White House Counsel is interesting. Hopefully he avoids going down the same path of lunacy he went down, IOTL.

McGoverning Bonus Content: The Big Damn McGovernomics Explainer

Any history – or plausibly alternate history – of the Seventies must be in large part an economic history, because economic change and disruption had so much to do with the decade’s fortunes generally. That trend was well underway by the time you inaugurate an American president in January 1973. Then, when it comes, the Oil Shock at the end of 1973 throws a big ol’ boulder into a body of water that was well churned up already.

What follows from there – what followed IOTL much less what might follow in an ATL – was not a single, uniform phenomenon labeled “stagflation and malaise.” There’s a powerful current of that in the big river but there were ebbs and flows and eddies and counter-currents, all sorts of interesting things. That’s especially true in this time window 1973-76, where for example inflation had already roughly doubled from 1972 levels before OTL’s Oil Shock, and where much of 1976 was marked by the strongest economic recovery of the entire decade, strong enough that it nearly bought Gerry Ford a second term.

There are mighty Trends at work in the macroeconomics of the Seventies, also. Through the Eurodollar market, or the creeping liberalization of credit and financial-trading controls in Western nations, and things like OTL’s inflationary international lending during the Seventies, you have key elements in what we might call the childhood of The Financialization of Everything IOTL. High-productivity – but especially low-cost – suppliers of coal, steel, and ships out of the Pacific Rim (and one or two other places) battered the market strength of those traditional heavy industries in Europe and North America. The Middle East became a political cockpit and center of geopolitical gravity when OPEC pulled off the largest single transfer of wealth up to that point in human history through the Oil Shock at the end of 1973 which entrenched structural inflation as a problem in the international economy right at a time when the overheated West found its growth in a secular slowdown.

Some of that inflation persisted in part because of a need to keep national economies growth-oriented enough to absorb both the massive cadre of Baby Boomers and adult women all entering the labor market together. (For some of those Boomers and a lot of the women, they ended up in service fields or as bureaucratic grunt workers in corporate organizations that mostly existed to shuffle paper for a living – the route from 9 to 5 to The Office is an express lane.) And as it happened, when inflation was finally, rather brutally, strangled out of national and international economies, those Boomers were able to acquire key assets (notably but not solely real estate) right at the start of a long era of unprecedented growth in value (or naked, untrammeled asset inflation, it sometimes depends how you look at it.)

So. Let’s get back to this specific period 1973-76. We’ll tackle the relationship between the McGoverners, swept unexpectedly into office in 1973, with what happened during this time window IOTL, then consider how McGovernomics tackles things differently. In order we’ll explore

All right, then. Are you sitting comfortably? Let’s do this thing.

Best and Brightest, Again?: The McGoverners of McGovernomics

One of the more important facets of McGovernment is the degree to which it reassembles the liberal-to-left portion of the Kennedy administration milieu, now shorn of its right wing – yer Dean Rusks, yer McGeorge Bundys, yer AG-era Bobbys – as the core of a new administration that, by its own lights, wants to pursue their old goals done right this time. That extends up, indeed, to the Kennedy administration’s former Food For Peace director, President George McGovern himself. It’s true throughout the administration, across a wide swath of policy subjects and administrative briefs. But it may be most the case in two specific fields within that swath – foreign policy as classically conceived, and macroeconomic policy. We’ll take on the latter here.

The core of monetarist economists (and to a lesser degree rational-expectations economists) have often been described over the decades as “the Chicago boys” for their ties to Milton Friedman and the University of Chicago’s economics and business departments more generally. By the same token, you could call the veritable Justice League of Keynes-adjacent economists (paleo-Keynesians, neo-Keynesians, a few vulgar-classical Keynesians, very-liberal-minded neoclassicists influenced by Keynes) that formed around George McGovern’s campaign and, IMyTL, his administration, the Boston Boys or alternatively the Mass Ave Gang. Let’s look at the policy-principals tip of the iceberg there.