Just a little something to tide folks over as I bounce back and forth on three consecutive chapters (the next three) just to bump the thread for readin' purposes and also to generate a little content for the faithful. So just for fun, here is a little taster of

Time magazine's year-end edition for 1972 in the universe of

McGoverning.

TIME MAGAZINE MAN OF THE YEAR

Charles Colson

"In the fall of dominoes that toppled a President, produced perhaps the greatest run of political scandal in United States history, and propelled another hair-raising, three way presidential election whose outcome defied the odds, Charles Colson was the conflagration's Gavrilo Princip."

Top Ten News Stories of 1972

1)

Brookingsgate

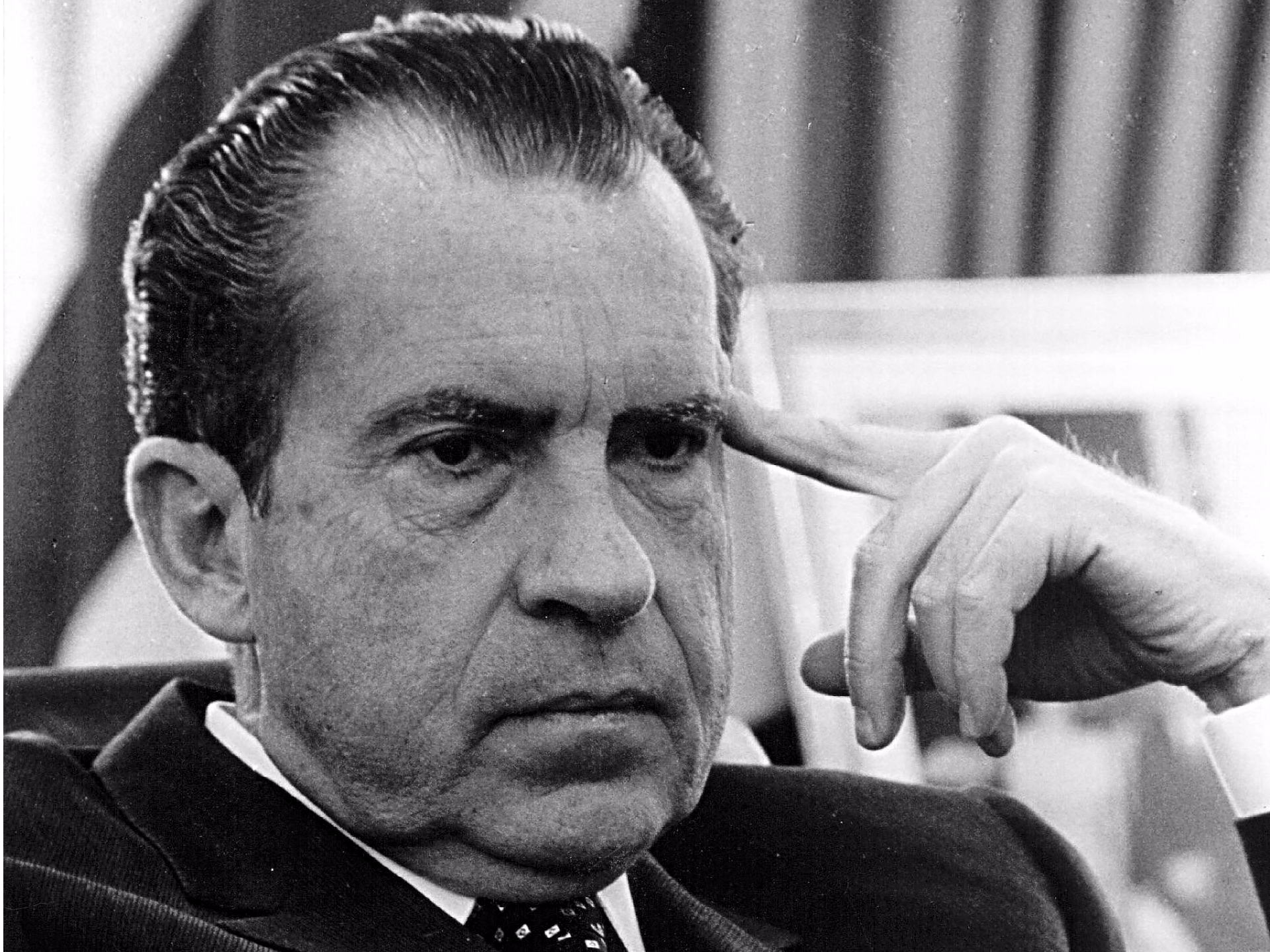

The Rosetta Stone of scandal in a year topped again and again by devastating political revelations, the firebombing of the Brookings Institution and concurrent attempted burglary at Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate Complex by the Potomac River drew together threads of corruption and criminality that placed the entire Nixon administration under its cloud. Offenders were uncovered, lawsuits commenced, criminal investigations stretched across the breadth of the Committee to Re-elect the President and into the White House itself. Revelations that evidence might be found in the secret tape recordings made in the Oval Office itself led the chair of a Senate investigative committee to sue President Nixon himself for access to those tapes. The aura of power, security, and inevitability that surrounded the Nixon administration faded in the face of chaos and corruption.

2)

The United States Presidential election

A drama of twists and turns in which the least likely outcome consistently turned up as the answer, the 1972 presidential election defied all its early expectations. The learned minds of Washington and the news business believed it would be a story of two coronations: first, of Ed Muskie as the nominee of the Democratic Party, second of Richard M. Nixon as the entrenched incumbent who looked set to create peace abroad and prosperity at home. Instead Muskie's campaign ended in spectacular fashion, and a breakneck race emerged in which the left-leaning outsider Sen. George McGovern (D-SD) rode a well tooled primaries campaign to the Democratic nomination. One major Democratic candidate, George Wallace, was nearly killed at the height of his political appeal in May; another, the familiar eminence of Hubert Humphrey, barely seemed to tolerate the Democratic National Convention's results. Nixon, on the other hand, still determined to make himself inevitable, saw that momentum fall apart over the summer after the "Brookingsgate" scandal erupted. From a wheelchair, George Wallace reentered the race, and a manic three-way contest of accusation and counter-accusation barreled through the autumn to its unlikely conclusion: the election, by a razor-thin Electoral College majority and a bare plurality, of George McGovern as America's next president.

3)

The Chennault Affair

Another political bombshell in a year full of them, this one was nonetheless so powerful that it produced a second wave of Congressional investigations, and perhaps brought a Nixonian bid for peace in Southeast Asia crashing down. It also marked the reemergence from the political exile of retirement of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who for a few weeks seemed both to overshadow his own party's nominee and to enjoy that thoroughly. The depth of the accusations -- that in 1968 the Nixon campaign colluded with the Saigon government to torpedo the early peace talks in Paris, against federal law -- took the air of scandal that already surrounded the White House and charged it with loose talk about espionage and treason. Johnson's own methods of investigation came under scrutiny as well, as no past administration's hands appeared clean. The compelling need to examine evidence in the case, however, aided Congressional investigators' cause as they pressed the courts for access to Nixon administration officials and their private papers.

4)

The Resignation of Spiro Agnew

Perhaps the straw that broke the Nixon campaign's back, the revelation by the Wallace campaign of Vice President Agnew's alleged acts of bribery and corruption in connection with Maryland state construction projects was the last great political explosion of the presidential race. That the story broke less than a week before the vote was no accident of timing, but rather an act of political genius -- or cruelty, opinions varied -- by the Wallace campaign. The result, which seemed to be among the clearest, most damning evidence of misconduct in any of the year's scandals, drove voters away from the President at the last possible minute. It also snared the man who seemed to be conservative Republicans' first choice to succeed Richard Nixon in 1976 from a place at Nixon's right hand into resignation from office in a matter of weeks.

5)

The Nixon Trip to China

This was the sort of event that Richard Nixon hoped would dominate the politics of 1972, both for his own benefit and because it had the potential to transform the Cold War and its relationships. The shocking diplomatic coup by which the President, his closest foreign policy adviser Henry Kissinger, and other key aides arrived in Peking to stage what amounted to a summit with Mao Tse-Tung and Chou En-Lai, grabbed the headlines like nothing else in the early months of the year. By this stroke, Richard Nixon seemed -- with the encouragement of the Chinese leadership -- to drive an even deeper wedge between Peking and Moscow, and perhaps between Peking and Hanoi as well. It seemed to offer new leverage for the administration in arms control talks, and to represent the rise of more worldly, pragmatic leadership in China, patronized by Chou En-Lai especially, after the bloody and radical excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

6)

The Journey of George Wallace

The most radical -- some said the most dangerous -- major presidential candidate of 1968, George Wallace reemerged in the 1972 election not once or even twice, but at least three times. First, he appeared as the loud, strong voice of blue-collar populists in the Democratic Party, having laid aside his most extreme views on segregation in favor of economic populism plus a healthy dose of law and order. This made him a powerful candidate in the primaries, until his near death in the assassination attempt of Arthur Bremer, a disturbed young man from Wisconsin, in Laurel, Maryland in May. After languishing for weeks in the hospital, near death and now paralyzed from the waist down, Wallace reappeared for the Democratic National Convention. There, he dallied with anti-McGovern stalwarts like AFL-CIO president George Meany and Sen. Henry "Scoop" Jackson (D-WA), and stole the thunder of the convention's end as he announced yet another walkout from the party. In the autumn, he rose again under the American Independent Party banner to outdo his 1968 results, draw away many Southern and Midwestern conservatives from the Nixon ticket, and deal the fatal blow to Spiro Agnew's career. Wallace was denied, barely, his goal of throwing the election to the House of Representatives. But his success in the face of continuous adversity seemed to show he had a true following in the voting public, whose effects on the two-party system are as yet unclear.

7)

Signing of the SALT Treaty

The other diplomatic triumph of the Nixon administration in a year that began so well for them, the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty seemed to offer the first fruits of the policy of

détente. The brainchild of Nixon himself, the treaty represents the first comprehensive attempt to curtail the arms race, to set a base from which further talks, already underway, could begin actual reductions in the superpowers' vast nuclear arsenals. Both its boldness in concept and the relatively conservative choices inked in the final treaty represent a testament to Nixon's wary pragmatism in relations with Moscow. They may also represent signs that, as Leonid Brezhnev emerges at the fore of the "collective leadership" that followed Kruschev, he seeks calm, though not actual peace, with the West while he consolidates power at home. In a chaotic year full of scandal and unpredictability, SALT seemed to say that there were at least some reasons for optimism in the world's political climate.

8)

War in Southeast Asia

As "Vietnamization" moved ahead and the US presence in South Vietnam grew ever smaller -- the last combat troops on the ground left in June -- it was nonetheless another roller coaster year in the long and bitter conflict there, with few signs of true resolution. In the spring, a direct invasion of South Vietnam by the North roiled the political climate, and seemed to threaten another Tet-like disaster for Western forces. Yet in the end ARVN lines held in most places, and a massive and controversial application of American aerial warfare, including strategic bombing above the Seventeenth Parallel and the mining of North Vietnam's harbors, ground the offensive down to an end. After that came a period of wariness and negotiation; in Paris, by October, Henry Kissinger seemed ready to announce that "peace was at hand." But the scandals of American politics, especially the revelation of possible foul play in the 1968 peace talks, helped throw President Thieu in against the compromise proposals Kissinger had crafted. Then [NOPE SORRY THAT'S GOING TO HAVE TO STAY REDACTED FOR RIGHT NOW] Where that then will lead may not become clear even in the new year.

9)

The Munich Olympics Massacre

It was a summer Games, a bright, pastel, buoyant Games. The Summer Olympics staged in Munich, West Germany, were built from the ground up to be the complete opposite of the grey, iron, Nazi Olympics staged in Berlin thirty-six years ago. At the start they seemed to be, with dachshunds as police dogs, tourists with balloons, and flower-power decorations for the world's athletes. There was drama in the sporting arena as well: the incredible medal haul of swimmer Mark Spitz, Olga Korbut's perfect score on the uneven bars in gymnastics, and the Cold War-style brawl between American and Soviet basketball players after the United States' last-minute victory. Then everything changed. Eight radical Palestinian

Fedayeen, well armed with Kalashnikovs and grenades, slipped through the absence of security and attacked the residence hall where Israeli athletes lived, shooting one wrestling official dead and seizing fourteen more Israelis hostage. After a long, hot day of negotiations in front of the dormitory with West German officials and Arab diplomats, the Palestinians and their captives (at one point paraded along balconies at gunpoint) made ready to leave by bus to reach Munich's airport. Then, there in the parking garage below the Olympic Village, Munich police bungled an armed ambush of the kidnap party. It ended in blood and fire, the small bus burnt out by grenades dropped by its fuel tank, with seven

Fedayeen, two Germans (a policeman and the volunteer driver) and all the Israelis dead. The decision to carry on with the Games brought the downfall of legendary International Olympic Committee chair Avery Brundage. Bonn's decision to hand over the Palestinian survivor to Israeli authorities prompted bombs at West German embassies in Egypt and Kuwait, which left another nine dead.

10)

The Apollo Program Ends

It was at times difficult to remember, during a year of scandals, wars, murder, corruption, and other careworn signs of the times, that humanity, at least its American branch, was busier than ever in space. More missions reached the moon, with more complex and detailed scientific projects carried out. NASA had every reason to be proud that, at least since the high drama over the Apollo 13 mission, now manned flight to the nearest object in space had become all but routine. Apollo 17 took advantage of that fact to stretch the bounds of their work with the longest-ever lunar orbit, longest mission on the surface, and longest moonwalks to date. The crew as well, ever professional, seemed to make complex experiments with lunar volcanology and cosmic-ray physics look easy. The only marker of the extraordinary year back down on earth was one mention, almost wistful, of Vice President Agnew's absence (the resigned vice president had always been a NASA supporter.) This year the Nixon administration guaranteed a new program for a space "shuttle" to handle orbital missions in support of manned satellites. But the allure of the moon now seemed to belong almost to a bygone era. The President-elect's convention message, to "come home, America," took a literal form as the last men to walk on the moon, for now, boarded their mission module and returned to the ground. With them they brought a photograph that took mere days to belong legend; what is known now and likely will be known, as the "Blue Marble" image. A whole earth, alive and small and fragile, glimpsed from another place. It was a valuable reminder in a difficult year.

(So you'll note the different writing style there on behalf of the

Time staff; titillation, stentorian judgments, and Both Sides Do It are

hardly new in the world of journalism....)