If Jim could do it without a degree....A certain Georgia amphibian is reconsidering his decision not to go to law school…

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

McGoverning

- Thread starter Yes

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

McGoverning Bonus Content: The Big Damn McGovernomics Explainer McGoverning Bonus Content: Fearsome Opponent - John Doar, Dick Nixon, and Prosecuting a (Former) President McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, People and Process McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, A Strategy of Arms McGoverning Bonus Content: Moment of Historiographical and Thematic Clarity McGoverning Bonus Content: A Strategy of Arms II McGoverning Bonus Content: On Cartographers McGoverning Bonus Content: A Cambridge Consensus?Right?If Jim could do it without a degree....

Gurney '76 it is.Here, pardoning Dick Nixon is a cause.

John Farson

Banned

Oh god, and Ted is his Robin... holy nattering nabobs.‘Tis an eldritch season…

By day, Dick Nixon plays piano and is exasperated by the hijinks of his newly-grown daughters. By night, HE FIGHTS CRIME!!

That's the thing: even if McGovern succeeds in 1976, there's still 1980 after that, and who knows what sorts of events foreign and domestic will occur that will affect that race and the eventual Democratic nominee. Even if McGovern himself happens to have approval ratings of 50+% at that time, that does not necessarily transfer to his would-be successor, as real-life has shown....now I have a bad, bad feeling about McGovern's successor.

It's a two-party system, to quote Kang and Kodos, and for every action in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction, to quote Newton. We have already seen the backlash to the civil rights legislation of the 50s and 60s, and Nixon's conviction threatens to become a cause célèbre - among several others, like Roe v. Wade - for the American right and far right that may very well expedite the process of political polarization that we have witnessed these past decades, so that the 80s may come to resemble OTL's 90s, which itself was a harbinger for things to come. It all depends on how long the Democrats can continue to hold Congress, especially the House.

It's a two-party system, to quote Kang and Kodos, and for every action in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction, to quote Newton. We have already seen the backlash to the civil rights legislation of the 50s and 60s, and Nixon's conviction threatens to become a cause célèbre - among several others, like Roe v. Wade - for the American right and far right that may very well expedite the process of political polarization that we have witnessed these past decades, so that the 80s may come to resemble OTL's 90s, which itself was a harbinger for things to come. It all depends on how long the Democrats can continue to hold Congress, especially the House.

True, but it does depend on the level of appeal. OTL, I would say that the Overton Window going to the right as it did was because of the economic situation. Thatcher and Reagan had been given undeserved credit for the economic recovery of the 1980s. This attribution of success to them gave them alot of validation for other socio-economic aspects that would be seen over in the culture wars.

I imagine the differing economic situations and so on would put a big wrench in that, especially since the 1980s are a very prominent pivot point. Where alot of the old guard begins to die out or retire and the boomers begin ascending to power with whatever beliefs and thoughts they come to accept as valid.

I feel like despite the almost STAVKA Deep Battle success of Doar and the gang in establishing the clear legal guilt of Nixon in particular and the executive office in general principle, there may have been just a tad too much disregard for the production of it all as an exercise of the state perpetuating itself and redefining itself. Even as important as it is as a legal principle obstruction is maybe just a bit too thin to hang "the trial of the old regime" on when you really could have made Dick the next Al Capone. And yeah that is what this was always going to have to be, when this is all part of burying the evils of Nixonism and Vietnam and healing a broken America under the radical new McGovernment understanding of the American state.

I like several of the allusions here, and want to draw attention to the "trial of the old regime" element. There's definitely a direct element of that to the prosecution of the Nixon crew, and I'd say that it's more true that McGovernment's supporters and followers - the political interests in the broader American national community who were most excited about a McGovern candidacy and McGovern presidency - who are most likely to embrace the notion that this puts a bad system on trial.

For a number of key McGoverners themselves - who include George Himself - they prefer to understand the legal-political process of bringing Nixon to book as a reassertion of first principles and old virtues. It's been true probably since Hammurabi that systemic reformers often like to dress those systemic reforms in forms and language that suggests that change is instead a restoration of historic values and ideals. Before the French come along and really go wild with the concept, in 18th century English "revolution" - the term the colonists in British North America use for their revolt - referred to a reset back to the original operating system, if you will, a triumph of recovered virtue over authoritarian decay. (Also that was shifty and self-congratulatory as all hell for the well-read profiteers of plantation slavery - New England very much included - who launched the revolt, but that's another discussion for another time.)

That's part of how, as well as why, the McGoverners get hung up on the possibilities tied to the obstruction charge. Nixon broke not only the law but the rule of law itself, and here we got him to admit his guilt in court! It seems, to those McGoverners, like a vindication of the ideals they want to uphold, that they want to take in new directions (like for example, "maybe our historic embrace of government by the people should include women and people of color, on a really good day perhaps even queer folk?")

It's hard now, fifty years out, and with realities like the Red Scare and the bloody-handed ideological warfare of the Sixties involved, either to recall or to understand that some folks involved at high levels in American politics and administrative governance genuinely had a soft spot for an idealized understanding of the "official version" that the US had a dented-but-unbowed history of constitutional liberalism that leaned over time towards the left hand of that liberalism. But some did, and there was a high - or at least highly strategic - concentration of them around the McGovern movement and the "McGovern moment," turned up to eleven here by the fact that they actually won in '72.

It's their blind spot, of course. It would indeed make more of an impression if you dragged the evidence of every sorry RICO misdeed by the Nixon crew through the courts, much as the encyclopedically detailed transcriptions of the Oval Office tapes IOTL wore away at Nixon's carefully crafted public image. But the McGoverners are fueled by the principle of the thing - sometimes principles obscure the contours of reality, something McGovernment has ample opportunity to learn.

Where's Roger Stone in all this?One thing I'll say here is this, for us to sit with before we go from this place. Here, in the world where George McGovern won, a Nixon pardon is not a historical turning point where America failed to turn. Here, pardoning Dick Nixon is a cause.

I'm sure he'll slither out from under a rotting tree trunk at some point; though he was lower on the Nixonian food chain in those days he is ever on the make.Where's Roger Stone in all this?

No doubt hiding after his attempt to destroy Toontown failed miserably.I'm sure he'll slither out from under a rotting tree trunk at some point; though he was lower on the Nixonian food chain in those days he is ever on the make.

But will be exciting how else things will go here.

No doubt hiding after his attempt to destroy Toontown failed miserably.

What you did there. It was seen. (And some of us saw that in the theatre, btw.)

Thanks! I mean, the resemblance is uncanny.What you did there. It was seen. (And some of us saw that in the theatre, btw.)

Will be interesting what happens next.

McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, People and Process

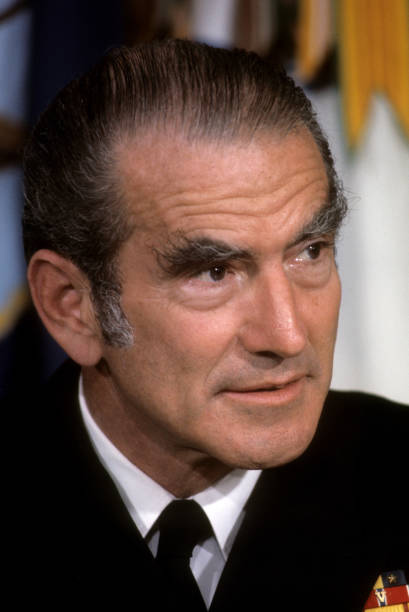

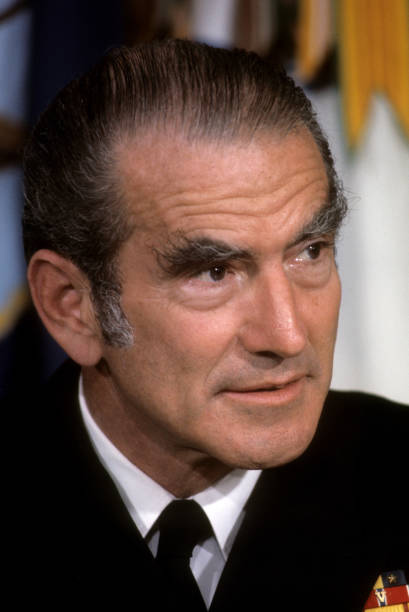

President George McGovern briefed by the Chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff, Adm. Thomas Moorer, during the withdrawal

of US forces from South Vietnam in early February 1973

This post starts a limited-run Bonus Content series on a topic that's not necessarily the first we'd think of when it comes to McGovernment: defense and national-security policy. (Hopeful that, along the way in coming months without compromising the Drive For Narrative, there will also be Another Big Damn Health Care Explainer, perhaps also a couple of entries on energy policy at some point down the line. For my own personal joy, when we get to the end-of-December holidays, there might be a single Bonus Content post conjointly aimed at avgeeks and railfans. But we'll start here because there's a backlog of useful stuff in the Scrivener files and Google Docs.)

On one hand, defense/natsec issues definitely were not a field of policy where George Himself, along with some other senior McGoverners, even more so the demographics among the American public who cheered wildly when George won the day in November 1972, wanted to focus their efforts and time. But one of George's very, very first orders of business after he takes the oath of office is the physical extrication of American servicemen (and a small but growing number of servicewomen) from the least popular and most controversial American war of the 20th century up to that point. Also McGovernment (1) sees root and branch reform of both American geostrategy and the military-industrial complex as a key part of remaking the post-1945 American project and (2) hopes that significant cuts in defense spending will free up budget dollars for the sort of public policies with which McGovernment seeks to rebuild the nation at home - national health care, what I've already termed a total-employment policy, urban rejuvenation, pollution abatement etc.

So what we can reasonably call McGovernment's left wing (even its pragmatic middle) sees the task to reform and resituate the mighty High Cold War national security state as a necessary part of transforming the American state more broadly. Then there are also major geostrategic and policy implementation issues that any presidential administration would face in 1973 with the ink on the Paris Agreements not yet dry. Here we'll do something we haven't yet (commonplace though it is in many a TL) and draw on a Watsonian source (indicated by its different typeface), the McGNU's own version of the handy volume The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy, 1973-76:

Any administration that entered office in 1973 would have faced a host of major national security issues and challenges: about the United States’ global presence and strategy after withdrawal from Southeast Asia; about the scope and future of detente; transitioning to a volunteer military; budgetary issues tied to the debate over whether to expand or constrain force levels and modernization after Vietnam; how many and what sort of wars the military should be equipped to fight; the growing strategic importance of the Middle East; and so on.

The McGovern administration entered office attached to political desires and concrete policy goals that marked a sharp, even divisively dramatic, break with American Cold War conventional wisdom up to that point. Distrustful of the military-industrial complex and of geopolitical overstretch, “McGovernment” sought fiscal constraints that would sharply reduce defense spending, programmatic and structural reforms for a leaner and more efficient military, dramatic forward progress on arms control, lessened foreign military sales, and force drawdowns on America’s overseas military establishments in Europe and the Pacific Rim. On one hand, the administration sought to mobilize Congressional retrenchment against expensive overseas power projection, along with public suspicion of military and intelligence overreach. On the other hand, the unexpected electoral success of “McGovernment” was politically tenuous, a vocal minority in its own political party, dependent on relations with a political system that sought on many fronts to constrain its ambitions.

That's a fair summing up. Note especially that last sentence which we could stress more often in even more fields of politics and policy: Our Brave Heroes have to deal with the fact that, although they control the Executive Branch as a faction within the party that's held the presidency (up through 1976) all but twelve years since 1933, within the bigger ideological/factional ecosystem of The Beltway they're a minority force, who have to figure out how to govern anyway.

We can, though, discern three processes/characteristics to do with policy development and implementation here, on these issues, that are entirely in common with McGovernment policymaking on pretty much any and every issues. They are

- McGoverners have to haggle out the granular details of the policy they intend to pursue

- That often involves debates between McGoverners who follow competing logic chains about best process/outcomes (remember that economic compare/contrast on Jim Gavin and Les Thurow, for example), also between Reformers fully committed to the McGovernite project and Regulars brought into the administration for their political/administrative experience

- There's a surprisingly wide range of policy possibilities in the tumultuous, unsettled early-to-mid Seventies (true of many different fields of policy) a lot of fascinating concepts that got an airing - they largely died on the vine IOTL as grimly small-c conservative presidential administrations trudged through the Era of Limits, but here in the McGNU with an activist left-liberal/social democratic administration determined to Change Things, there's much more opportunity for those options to get a more detailed airing, and for the pursuit of some of them

- Then there's what happens when the policy plan makes contact with (1) institutional Executive Branch interests, (2) Congress, plus (3) the very populations and institutions the policy/ies affect

All righty. Seated comfortably? Let's light this candle.

*********************

Two parts to this post (well, three really, but two from here on out.) Just as the threadmark says. Ya got yer people - can't tell the players without a scorecard - ya got yer processes/structures, at least a few of the really key ones. Some - many - of the working bits key to the larger story. We'll start at the top and work our way towards a very specific subset of Permanent Washington, aka the uniforms.

First Principals: George and the Big Four

Don't hate me because I'm beautiful.

This starts at the top, as one does with any administration especially after the False Sun rose at Trinity and ushered in the nuclear age. Any given president, per the various provisions in Article II of the Constitution, is both the Commander in Chief of all US federalized military and military-adjacent forces, and the Chief Executive with direct oversight and ultimate managerial control over the biggest baddest department-of-departments in the whole DC bureaucracy, the Department of Defense. Let's dip back into that "primary source" for a bit more (NB: the Watsonian voice of this specific source tends to favor the institution involved, and its caretakers, relative to johnny-come-lately politicians of all descriptions, though you get between-the-lines plaudits if you feed and tend the institution in the manner to which it's become accustomed.)

The scope and scale of change ushered in by President George McGovern’s inauguration started with the chief executive himself. McGovern had won his party’s nomination for the presidency as its most consistent, dogged, and often strident opponent of the war in Southeast Asia, the politician most determined to end America’s role in that conflict by any means necessary. President McGovern’s relationships with both the uniformed services and the broader national-security community thus began on pointed terms that accentuated, rather than muted, existing internal divides. Yet, by an irony of timing, McGovern inherited the freshly-inked Paris Accords as a means to his end in Southeast Asia. In the longer term, national security policy during his tenure was shaped more by the broader, more enduring elements of McGovern’s ideology and character.

A professional historian by training, McGovern was a well-read, engaged, and frequently iconoclastic student of foreign policy, with a natural facility to think in terms of grand strategy. By the time he reached the presidency, McGovern’s views were a blend of his perspective on what he saw as conventional Cold War policy’s indicative failure – America’s intervention in Southeast Asia – attention to the ideas of other reformist critics in the public conversation about foreign policy, and a mixture of older Progressive and Wilsonian influences from his youth.

President McGovern’s role in his administration’s defense policy, and his relationship with defense policy’s principal actors, could be described as dialectical – a process of understanding the tensions and ties between contrasts. Even among career uniformed and civilian officials who might dislike or distrust McGovern’s policy objectives, he was noted for his calm modesty, his personal decency, and his thoughtful personal relationships with key figures. Even McGovern’s frequent policy opponent, his first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Tom Moorer, believed that McGovern had the most courteous and respectful personal relations with chiefs of the uniformed services of any president since Eisenhower. Though McGovern devoted much – most – of his time, with the exception of arms control, to non-military foreign policy and domestic issues, he was a quick and intensive study when given specific subjects to manage and reliably gave all his contrasting advisers a hearing.

McGovern’s personality and methods came with complexities and complications, too. His habit of listening carefully to all principal sources of advice sometimes left those principals confused as to what position McGovern himself supported. When not personally invested in a subject or situation, McGovern tended to let his principals get on with their work, which avoided micromanagement but sometimes left his deputies at sea as to how intra- or interdepartmental conflict would be resolved. On rare occasions, McGovern took quite the opposite approach and seized the reins of the policy process directly, a jarring contrast to the more frequent laissez-faire. Some quite granular matters, including the fate of specific serving officers involved in hot-button matters, rested ultimately on McGovern’s moral compass, more than on a considered view of the situation’s role in a broader strategic or policy landscape.

To be fair, given the Watsonian pov, that's not an unfair assessment. Especially the last paragraph, which is one to keep in mind across the whole ambit of foreign/natsec and also domestic policy. It's a natural Watsonian extension of the Doylist data we have from OTL's 1972 presidential campaign, among other things. In the interest of time we'll move on to the "Big Four" of McGovern's relatively small, relatively tight-knit natsec/defense policy leadership. Or, at least, three of them - we'll come around to the fourth when we get "inside the Building" over at the Pentagon.

The linchpin

The central figure in the whole foreign/natsec/geostrategic policy sphere for the McGovern administration is Paul Warnke. He'd been George's senior adviser on such issues during the campaign; they have a strong personal relationship, plus for George that essential trust in Warnke's loyalty, that makes an especially tight and also untypical bond for the notoriously private, inward-facing President McGovern. Really George wanted to make Warnke Secretary of Defense, an idea for which Warnke's law-firm partner and political patron Clark Clifford had a sentimental fondness also. But George's powerhouse transition team (FRANK! Mankiewicz, Clifford, Larry O'Brien, and Ted Sorensen) believed the GREAT GOD STROMs and Scoop Jacksons and such would eat Warnke alive in confirmation, so Warnke became George's National Security Adviser instead purely by presidential appointment. Is that a relationship not totally removed from The Dick and Henry Show? Not totally removed, but also it's different because of - just no other way to say it - the specific character of the people involved. Warnke's a bulldog, sure of himself just to the envelope's edge of arrogance, and relishes a good debate. But he also knows how to get on with people and values a collegial model of decision-making, in line with George's desire to hear from all of his folks as he (George) weighs the choices. No kitchen-cabinet diplomacy here. On the other hand, George and Paul Warnke share a great many perspectives and opinions, and George values Warnke's knowledge and judgment on natsec issues much as Warnke does likewise with George on "soft power" diplomacy and geostrategy. It's a central and largely productive partnership, but also one where Warnke has that extra bit of pull with George over and above other players in the process. Also Warnke has a small but vibrant "shop" in the West Wing: his National Security Council staff who are an extraordinarily distinguished and talented bunch from among the possible hires who'd share at least a broadly McGovernite or McGovern-adjacent view of policy.

The lover

SARGE!! Everybody loves Sarge; it's his superpower. You simply should not accept a substitute when it comes to someone who can sit right down with the world's leaders like he's known them from boyhood, gab for hours, and slowly charm them in a direction of idealism and human decency. One of the great Doylist (also Watsonian, really) pleasures of the McGNU is that here Sarge isn't just stuck with the bucket of warm piss, here he gets to do what he's really really good at. That's a net plus for the administration in several ways, not least because Kennedy-fam Sarge is the kind of media magnet that the media yearn for and feel they've been short-changed with since "Mister Magoo," aka President George Stanley McGovern, bushwhacked Nixon. Everyone wants to see Sarge and Eunice at Stade Roland Garros in Paris while Sarge checks in on the Rambouillet Talks, wants to see him pop on a beaver hat and tramp around Red Square with rosy winter-touched cheeks, etc., etc. It can even - and Sarge himself is quite good at this part - be good cover, that distracts the press from whatever serious foreign-policy work is actually going on. Through the magnitude of his sheer effervescent Sargeness, he's able to make himself a very significant wise-man figure in the administration's debates about defense and national-security policy. He has a boldness about him too - when he sees what he thinks is a way forward he'll preach it and lean in to make it happen. Also he carries a vigorous and robust brief for Foggy Bottom in shaping those debates, that process of integrating what are often military or at least intelligence issues into an actual broader geostrategic framework (more on that in a bit.)

The fighter

The third of these three, Director of Central Intelligence Pete McCloskey, is a little farther outside the inner sanctum where Paul Warnke has a comfortable chair and Secretary of State Shriver at least a Sarge-sized foot in the door. Nevertheless, McCloskey is a central figure for a few reasons. First, because he has a remarkably important job in his own right (to which good chunks of a coming chapter will be devoted), namely cleaning the stables in the US intelligence community at the end of a quarter-century of ever-increasing excess and not-infrequent criminality, without either being torched by bitter-enders or collapsing the institutions entirely. That would be enough to occupy anyone's time, but on top of it he's a central figure in the intelligence-gathering entwined with the arms control process, and with a growing US intelligence footprint in the Middle East. As pugnacious as he is thoughtful (and the ex-boxer is both), McCloskey's tough enough for the stable-cleaning job, question is whether anything might get in the way of that. McCloskey also belongs to a very interesting subset of McGoverners: like others of this specific subset, McCloskey doesn't object to the use of military force as a tool of American grand strategy - but it needs to be a tool of an actual grand strategy, a means to a well-conceived end, not a substitute for such strategy as it so often is in the American policy experience, because that (per McCloskey) is the kind of bullshit that's done such grievous damage both to the actual US military and to the American national fabric through the rotten imperial war in Southeast Asia.

On Seeing the Elephant

One of the crowning ironies of the McGovern administration, pilloried by its enemies as a bunch of weak-kneed pinko pacifists, is that the McGovern administration's senior leadership, especially on natsec matters, has more collective combat experience than any OTL administration of the 20th century, even OTL!Reagan's. George Himself of course flew a few dozen combat missions as a B-24 pilot. Vice President Phil Hart (WE LOVE YOU SO DAMN MUCH PHIL) nearly lost the use of an arm to a German sniper fighting on the Normandy beaches, then recovered and returned to the fight in the spring of 1945. Sarge Shriver was wounded aboard the battleship South Dakota off Guadalcanal. Cy Vance saw action as a gunnery officer aboard a destroyer. Vance's deputy at DoD, Townsend Hoopes, was a young Marine lieutenant on Okinawa and then the junior military aide to the first three Secretaries of Defense. Paul Warnke served in the oceangoing Coast Guard, hunted by U-boats in the North Atlantic and dive bombed by the Japanese in the Pacific. George's personal consigliere Frank Mankiewicz fought in the Battle of the Bulge as an enlisted infantryman. Pete McCloskey won the Navy Cross and other medals in Korea as a young Marine officer, and at the time of his appointment as DCI was still a military-intelligence colonel in the Marine Corps Reserve. It matters both to how they consider these issues, and to their relative levels of credibility with the Permanent Washington natsec bureaucrats and career uniformed military, that so many of them have seen the elephant.

Inside the Building: East(ern Establishment) at the Top

The most dutiful man in DC?: Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance

Cy Vance is not the most exciting star in McGovernment's galaxy of policymakers. Never gonna light up the stage at a McGovernite tent revival, for example. He is, though, one of the most crucial McGoverners, and some of the most crucial parts of what he does on the job, in McGovernment's case, are as luck would have it the things he does best. It is very likely - indeed for Yr. Hmbl. Author & C. it's canonical - that he just doesn't get enough credit for that. But he's Cy Vance - he does it anyway because it's His Duty and also The Right Thing to Do. That's just how Cy's motherboard is wired. We'll consider that for a moment. Back to our "source" !

A man of the Eastern establishment (tapped for Scroll & Key at Yale, followed by Yale Law School, naval combat service in World War II, and “white shoe” law in New York City with ties to Averell Harriman's political and business machinery), Vance rose through the DoD during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations as Secretary of the Army, Deputy Secretary of Defense and, after his resignation from that position, as a key envoy at the Paris Talks. Liberal by temperament, Vance became an opponent of escalation in Vietnam and a quiet but genuine supporter of President McGovern’s campaign in 1972. Vance was perhaps ideally positioned for his role in the incoming administration. He agreed with, or at least had empathy for, President McGovern's broad goals. At the same time this was mixed with extensive experience at DoD, a level of both comfort and capability working with Pentagon bureaucracy and with senior uniformed personnel, and a deeply ingrained ethic of duty and public service.

An able administrator with a breadth of skills, Vance’s special knack at DoD was as a facilitator, mediator, and most of all an honest broker trusted and respected by all the major players in defense policy formation. Even when those parties might disagree bitterly with one another, they trusted Vance as an arbiter. Figures as divergent as John Holum and Gen. Alexander Haig respected Vance as their boss and valued him both as a patron and a personal friend. A wide range of internal and external observers believed Vance held together the policy process at DoD and prevented much greater, more damaging, disagreements than those that existed during the administration. Vance was also able, patiently and thoughtfully, to educate wary service chiefs about the strategic logic of “McGovernment” goals on one hand, and McGovernite reformers about the realities of Pentagon management or defense industrial policy on the other.

That really says a lot of it right there, both who Vance is and why he matters. (The part about Al Haig is quite true, we'll get on to that given time.) McGovernment not-even-fucking-around-here desperately needs exactly what Cy Vance brings to the table as SecDef, else management of national security issues and civil-military relations could be a galloping dumpster fire from day one and - still the Cold War here, folks - doom the administration's credibility with Congress before any of the cool domestic/geostrategic stuff could even get out the door. Vance does a quite staggering amount of Watsonian load-bearing here and that makes a very serious difference. We can be pretty sure things would not actually have gone that well with Warnke's personal approach and nakedly McGovernite agenda. If we want to go full Cultural Revolution here we could call Vance a "Left-Regular With Reformist Characteristics" which is a truly essential straddle.

Go on, go full Whiffenpoof

If you thought we were done with the Eastern Establishment's soft-left wing so readily drawn to the McGovern flame, not hardly. Tim Hoopes, Vance's DepSec, is as much if not more of the breed than Vance himself: Hoopes was a Philips Exeter lad, then Yale Skull & Bones, and captain of one of Yale's last really competitive football squads. Hoopes was then a young Marine Corps officer on Okinawa and in the early occupation of Japan, then a military aide to all three of Harry Truman's Secretaries of Defense. After more of the same sort of white-shoe law Vance did, Hoopes became one of Paul Warnke's senior aides when Warnke was Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, and went on to be Assistant Secretary of the Air Force. Hoopes was also a keen and accomplished writer and amateur historian: his book about the turn from LINEBACKER bombing to the Paris Talks on the Johnson administration's part, The Limits of Intervention, sold well and, as IOTL, Hoopes wins the Bancroft Prize for American history for his magisterial The Devil and John Foster Dulles just as, IMyTL, he (Hoopes) takes the job as DepSec at the Pentagon. Hoopes also has a lot of gritty practical work to do under the McGovernment schema for DoD but we'll come back around to that in a bit.

Les Enfants Terribles: the Policy Shop

One of the things that McGovernment does with DoD - this came up with the org charts post a few months back - is create a series of "horizontal Undersecretariats" one layer below Tim Hoopes, for subject matter dealt with by all the services. Four, in fact: Reserve Affairs, Intelligence, Resources & Procurement, and Policy.

We'll take just a moment to mention Reserve Affairs' boss, a pleasantly competent career Beltway guy by the name of Norman Paul. Paul had been in admin with both the CIA and one of the predecessor entities for USAID during the Fifties, then served in several key DoD gigs during the Kennedy-Johnson years, notably Assistant Secretary of defense for Legislative Affairs, ie the guy who deals directly with Congress on the granular details. Very safe pair of hands.

Now on to the interesting stuff. There are several places inside the McGovern administration - notably the West Wing itself - where small clusters of ambitious, high-achieving thirtysomethings have surged forward to make both a name for themselves and a substantive role in McGovernment policy. At DoD in McGovernment days that would be the Undersecretariat for Policy.

There are four key jobs in the Policy undersecretariat. They are

- The Undersecretary themselves, who runs the whole policy shop and coordinates/provides editorial control over the activities of his main subordinates

- The Assistant Secretary for International Security Affairs, responsible for international defense policy, coordinating security cooperation through alliances and other organizations, foreign military sales programs, and at this stage also participation in arms control negotiations

- The Assistant Secretary for Strategy and Plans, whose job is exactly as enormous as that sounds for the combined military forces of a superpower, and also

- The Assistant Secretary for Doctrine, who has an especially significant granular job working with each service to develop and disseminate doctrine - which, in practical terms for the US military, means the "how-to" manuals for the various aspects of what each service does, or does jointly

- Undersecretary for Policy: John Holum (turned 33 in 1973), was in the years immediately prior to his presidency, one of George Himself's key kitchen cabinet members out of the McGovern Senate office. With a BA in physics and a law degree from Georgetown, Holum was George's policy maven on several fronts but especially the thorny issues of defense policy. Holum was also the principal author of the McGovern campaign's provocative Alternate Defense Posture of January 1972, which we'll come back around to in the next post. A dogged policy guy with a penetrating intelligence - also, culturally, very much a High Plains Midwesterner like POTUS and in his (Holum's) spare time an accomplished bluegrass banjo player - Holum takes the job both as a reward for his indispensable work for George and as the official McGovernite devil's advocate/"murder board" inside the Building, there to pick apart official justifications for force postures, weapons programs, etc. and see if they actually stand up to scrutiny.

- Assistant Secretary for International Security Affairs: Leslie Gelb (turned 36 in 1973) gets treated as a combination of the grownup in the room and "gramps" by his slightly younger Policy colleagues. Gelb was Paul Warnke's deputy for arms control, among other matters, when Warnke held what's now Gelb's job, but by far Gelb's biggest task at DoD then was to lead the 36-member team that compiled the forty-seven volumes and over 7000 pages of what we know as the Pentagon Papers. Here in MyTL!1972-73 during the presidential transition, Gelb is headhunted from his cushy gig with - you don't even have to guess do you - Brookings for this job, someone who brings a combination of sympathy for McGovernment goals and familiarity with both the system and the permanent staff at DoD.

- Assistant Secretary for Strategy and Plans: Jeffrey Record (turned 30 in 1973) is the youngest of these four young guns, but possibly the most thorough, well read, and meticulous thinker out of all of them - or at least it's a footrace. At this point Record's served as a civilian in South Vietnam on a provincial reconstruction team, then sailed through his Johns Hopkins PhD with accolades to a high-flyer's position at - yup, again - Brookings. We'll see a lot of his, and John Holum's, views and work when we get to the next post in this series. (IOTL he went on to decades of distinguished work with several think tanks and also on Sam Nunn's staff - Record's probably to Nunn's left in general, but not quite so much so as Holum; more to the point defense-reformer Nunn thought Record was the brightest guy in town on such subjects.)

- Assistant Secretary for Doctrine: Here's where we meet the Reformers-and-Regulars dynamic at the Policy shop. R. James Woolsey (turned 32 in 1973) is yet another high flyer, a lower-middle-class kid from Tulsa who shot up through distinguished collegiate and law school work to serving on the early SALT negotiations staff during a brief stint in the military and then, where he's headhunted by the transition team, as the general counsel for Senate Armed Services. Already by this stage Woolsey's more of the Scoop Jackson wing of the party (probably even on the left of the Jackson wing in matters of domestic and macroeconomic policy, so those parts of McGovernment aren't a turnoff), but he's ambitious and ready to take a flyer on getting experience inside the Building with a Democratic administration that's hard-up for filling a lot of these mid-level policy formation jobs. Incoming Secretary Vance thinks Woolsey will get on with the serving flag officers in charge of their respective services' doctrine shops, and that's enough to get the gig.

Spooks and Boffins - Intelligence and R&P

A rare photo of Ted van Dyk in the Seventies, to

the big guy's left

The Intelligence undersecretariat at DoD is, in fact, a pretty big deal. For one thing, administratively it "owns" the biggest chunk of the US intelligence community that's not run out of Langley: you have, below the Undersec for Intelligence, each of the National Security Agency (NSA's already well on its way to being the entity we know and are silently freaked out by), the National Reconnaissance Office (in charge of much of US spy satellite infrastructure) , and the Defense Intelligence Agency, among others. Collectively those entities have a crucial role understanding Soviet capabilities, both current and in the R&D phase, those of other potential adversaries around the world, and sometimes even of US allies. In a McGovern administration DoD, the Intelligence bailiwick is also a resource in the reform-vs-regular debates because if you want to cite sources and data in support of your arguments, whichever side in a given debate you're on you go to Intel for the crunchy crunchy info.

Unlike the policy shop, Intel is run by one of the most significant Regulars in the McGovern constellation. Ted van Dyk grew up a smart working-class kid in Washington state and worked his way up the Democratic Party machinery to become a senior aide to Hubert Humphrey with a side line in military intelligence analysis. Ted was a significant Humphrey advisor during the '68 campaign but, because of his deep personal opposition to the Vietnam War, sided with George in '72 and served as a senior policy consultant for the shoestring early campaign on a variety of issues. Here - though some members of George's transition team hoped to find Ted a job in the West Wing itself - he gets a significant policy gig as reward. Very much a Regular, skeptical of what he sees as some of McGovernment's more idealistic or aspirational views, Ted's poised to get along pretty well with the career intelligence hands both civilian and uniformed. He's also a respectful sparring partner on policy with John Holum - we should emphasize this because it's important, the "respectful" part that is. Ted and Holum like each other well enough personally, and respect the work each other did for the presidential campaign, so while they're more-than-sometimes given to disagree or at least debate, that has a collegial, professional tone.

Bright ambition

"Amateurs talk tactics; professionals talk logistics" - on that basis, the Undersecretariat for Resources & Procurement is maybe the driving engine of the whole DoD. Here, in McGovernment's version of that organization, certainly it includes both those very logistical streams and operations which allow a Cold War superpower's military to function with all the necessary beans, bullets, motor oil, tent flaps, ship propellers, etc., required in the effort, and the in-house industrial management process of research & development, program management, cost accounting, on and on, for the most coordinated part (we'll leave aside the debate over value judgments here for now) of American industrial policy. It's a big job - and, potentially, a very useful apprenticeship.

Certainly that's how Harold Brown sees it. From a secular Jewish family in lower-middle-class Brooklyn, Brown was a one-man meteor: a child prodigy who'd earned a PhD by twenty-one, and by thirty ran the Livermore Laboratories, where he played a key role in the development of nuclear warheads small enough to fit to the Navy's Polaris missiles. The Kennedy administration put him in charge of R&D at the Pentagon and Brown again worked his way up to spend the last couple years of the Johnson administration as Secretary of the Air Force. Brown's a meticulous, driven guy, not afraid to give flag officers a dressing down if he feels they're doing the job wrong, one of the most accomplished technocrats in the business, and he has plenty of ambition. Running the working engine of the Pentagon is for Brown a job with a larger purpose. Brown had been Tim Hoopes' boss with the Air Force, but Hoopes had more personal connections with the McGovern camp - more to Brown's point, however, Tim Hoopes has no real ambitions to be Secretary, which means that whenever Cy Vance wearies of the job at the top, after this stint running R&P Brown genuinely would be the most-qualified man in the country to become a Democratic president's SecDef. Least that's what Brown hopes.

Serving the Services, Watching the Watchers - Service Secretaries and the Inspectorate General

Yankee sailor, line one

It is still true - perhaps more so through McGovernment's institutional/process reforms at DoD - that the service secretaries play a very substantial part in the ordinary running of the specific uniformed services, especially things like baseline procurement, daily maintenance and running, training and career development of personnel, service equipment wish lists, and the rest. The McGovern team's Secretary of the Navy, Otis Pike, is a well-known and fairly senior Long Island congressman, Marine Corps pilot during World War II, and accomplished lawyer. Pike was a moderate on Vietnam and a foe of intelligence community overreach, but otherwise got on reasonably well with the armed services through his committee work. He is, however, one of those flinty Yankee taskmasters with an instinctive dislike of fraud and waste; there are some major naval defense contractors who might be in for a bumpy ride.

Spark the trailblazer

One of my favorite retcons - Secretary of the Army Spark Masuyaki Matsunaga is a trailblazer of the first order. Born Nisei (American-born second generation son of Japanese immigrants) on Kauai in Hawaii, Matsunaga was interned together with his family after the heinous decrees of December 1941, and was one of the interned Japanese Americans who collaborated to help create the famed all-Nisei 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, with which Matsunaga fought and was wounded in action in Europe. After the war Matsunaga was a public prosecutor, member of the Hawaii state lege in the transition from territory to state, then a member of the House of Representatives (at-large to start, then HI-1 after Hawaii gained a second district). He's a tireless and ongoing advocate for declarative and financial reparations for Japanese internment, an adept policy guy on his congressional committees, known for his gentle, dry sense of humor. The Army could probably use a methodical healer who knows life as a poor bloody infantryman - so now they've got one.

Big corporate get, or especially dapper

fox in the henhouse?

If Otis Pike was a moderately generic choice for a Democratic administration to make and Spark Matsunaga - first AAPI executive branch department secretary - was McGovernment leaning in to its ideals, then Secretary of the Air Force David S. Lewis is one of those places where McGovernment confounds its own supporters with a deep reach from the bench of corporate America. A dapper Southerner from up-country South Carolina, Lewis was a Georgia Tech-trained aerospace engineer who found his way from the Martin to the McDonnell aircraft companies. Lewis climbed the full greasy pole at McDonnell - he managed (and contributed too at an engineering level) the project that became the famed McDonnell F-4 Phantom II, then carried on to become president of McDonnell Douglas Aerospace after the two companies merged in the late Sixties. That was in time for Lewis to oversee the final move into production with the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and much of the crucial early work on what would become the F-15. Success can breed enemies, though - Lewis was then promptly frozen out at MacAir by McDonnell heirs who wanted more control. He promptly jumped ship to General Dynamics as CEO, where he involved himself in development of GD's entry to the prospective Light Weight Fighter competition around the time that, in the McGNU, he's head-hunted to administer the Air Force. On one hand he has immense professional qualifications for the role; on the other it lets a very large military-industrial complex fox inside the military's own chicken coop. McGoverners at the top prefer to see the first clause in the previous sentence, though plenty of folk who otherwise would like to root for the new administration see the second clause as well.

That raises the not insignificant question of who watches out to make sure there's not waste, fraud, abuse of resources or privilege, or other malfeasance in DoD. There we reach a guy who is surely the closest thing in the world Cy Vance has to an actual crony. David McGiffert was a Boston scriver who scrapped his way up through Harvard Law (after a tour in the Navy late in the war) with such success that he landed at no less than Covington & Burling, aka Dean Acheson's law firm - yes that Dean Acheson - where McGiffert worked alongside the likes of Paul Warnke and Warren Christopher. McGiffert was enough of a success that he got work with DoD under Kennedy, rising to replace Norm Paul as Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs. Then, in 1965, McGiffert became Undersecretary of the Army, partly on Cy Vance's say-so (this is when Vance moved from ArmySec to DepSec) and in support of one of Cy Vance's besties, the then-new Secretary of the Army Stanley Rogers Resor (another Eastern Establishment man to his fingertips - when Resor married a Pillsbury heiress straight out of college, Cy Vance was Resor's best man.) Among other things in that gig, McGiffert was part of a special task force with Vance, Warren Christopher (by then Deputy AG), and a few others - after the shambles of National Guardsmen responding to the 1967 riots in Detroit and Newark - to see how they could, legally and in the most limited fashion, use federal troops in such emergencies thereafter. McGiffert's a dead clever lawyer and deeply loyal to Vance; it would be hard for Cy to pick someone more useful as Inspector General of the department.

Restless Natives - A Word About the Uniforms

We'll really get to meet the relevant players in the Armed Forces in the ensuing posts. But it is worth note that this is one of the rare places in Beltway bureaucracy where McGovernment (or really any administration) encounters a rich, deep, broad, fully-formed culture of long-service nation-state servants who believe they follow a specific, notionally-apolitical (we'll come back to that too) calling, a profession that serves the greater good for the longue durée no matter when politicians and ideologies come and go. With the sometime and rather limited exception of the Foreign Service, the truest analogue to, say, Sir Humphrey Appleby you're likely to find in the American federal state would be wearing a uniform. Indeed that's an actual complaint of a strain or two in the McGovern contingent - that, rather than following the profession of arms, a lot of Pentagon flag officers are essentially technocratic bureaucrats waiting to cash in on their subject-matter expertise aboard various corporate boards post-retirement. But the remaining warriors among them, too, are just as like to give a long sideways glance at change agents of all sorts in the political contingent, and the McGoverners are nothing if not agents of change.

Methods and Charts - Tools and Systems of Policy Formation

Let's take a moment to refresh our view of the McGovernment-adjusted org chart for the DoD. Have a gander.

We'll make it nice and big to enhance readability. You've got a variety of features/dynamics here.

- The DepSec handles management of the day-to-day with the services themselves, whose chiefs handle personnel, training, the economics of supply and logistics, basing, and so forth for the peacetime existence of the services

- Authority passes through the National Command Authority (POTUS aided by the SecDef) to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs on to the "Sicks" (supreme commanders, a bureaucratic nicety as McGovernment reserves "commander-in-chief" for the constitutionally-mandated one, i.e. POTUS) of the half-dozen unified commands after the work of the Hoopes Board (about which more in the second post)

- Then you also have the horizontally-integrated Undersecretariats who handle subject matter in common to all the services in order both to reduce duplication (if the services did that themselves) and support SecDef at a high enough administrative level to make the work "joint" in the Pentagonese meaning of the term

At the National Security Council level, where all the natsec interests come together and where Paul Warnke's prolific little shop does their thing, you have four kinds of meetings and three principal kinds of memos.

- Actual, fully-attended National Security Council meetings, which are relatively rare (McGovernment's average of once every 3-6 months is actually higher than many administrations') and generally to make sure that each of the various entities that get to attend the NSC are up to date on a few key matters

- Special Policy Group (SPG) meetings (under Nixon this was WSAG, the Washington Special Actions Group) which attend to specific emergent topics or crises on an as-needed basis

- Policy Review Committee (PRC) meetings that develop forward-looking policy on (1) broader issues or (2) larger specific topics

- Deputies meetings, essentially a subspecies of PRC meetings, where the number-twos of various entities hash out policy and procedural details intended to smooth the running for principals to make decisions and implement policy at PRC level

Warnke also played a pivotal role in policy formation for the administration. At President McGovern’s insistence – unless the president took on the role personally – Warnke chaired the Special Policy Group (SPG) meetings of National Security Council members that dealt with specific, emergent topics or crises, and also the Policy Review Committee (PRC) meetings that developed forward-looking policy on broader issues or thematic subjects like arms control, global food security, treaty alliances, relations with the Global South, or human rights policy. In terms of paperwork flows and administrative methods, the McGovern administration made the National Security Decision Memo (NSDM) system its central method to express presidential views and directives. Paul Warnke acted as chief manager of the NSDM formulation process – inputs from the key departments (State, Defense, Peace, Treasury, and the intelligence community) were received and glossed by National Security Council staff – and interlocutor with President McGovern for the draft process of final NSDMs. Such means and measures as these put Warnke at the heart of policy processes.

The NSDM system was buttressed by two streams of supporting documents: National Security Study Memoranda (NSSM) generated largely out of the National Security Council staff and commented on by other principal agencies or partners, and Policy Review Memoranda (PRM) introduced by the McGovern administration as working documents for the Policy Review Committee’s deliberation process. Taken together they made the NSC system the principal factory of joint policy discussion for the administration, thanks especially to the prolific work habits of Paul Warnke’s staff. This kept the White House itself at the center of the policy process, even when President McGovern was often only personally concerned with some specific elements of foreign and national security issues, often occupied instead with domestic policy concerns.

As to how the Pentagon puts together its largest collective planning efforts, this also

The McGovern administration inherited a complex – many administration civilians said needlessly byzantine – overlaid defense planning process. After administrative discussions begun the day before President McGovern’s inaugural, within seven weeks the processes and procedures were boiled down to three large planning documents, each with their own structure and planning process.

- The first major planning task taken on during a presidential administration would be a Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), designed to be completed in time for the administration’s first budget cycle, covering all four budget cycles of that term. Developed collaboratively with the planning entities internal to DoD, especially the Joint Staff, the QDR would act as an administration’s first considered statement of intent, one that laid out strategic assumptions, policy goals, structural plans, and procurement requirements – in broad terms – as a baseline for plans and action during the actual four years of the presidential term.

- The primary short-term planning document would be the Joint Annual Strategic Plan (JASP), again produced during the planning phase of the fiscal cycle. Some administration reformers initially wanted the plan to be biennial, in order to encourage further fiscal discipline with expenditure plans made over a two-year span, but Secretary Vance ultimately sided with the argument that this was insufficiently responsive to major changes in circumstance. The JASP was divided into four Titles, all collected as a single document. Title One (Objectives) would lay out the desired strategic objectives of the plan. Title Two (Capabilities), often referred to as “the shopping list,” would cover the submitted capabilities requests from all relevant sources, tailored to the objectives under Title One, with supporting arguments. Title Three (Fiscal & Forces) would lay out that year’s current Four-Year Fiscal Plan (FYFP) for the next four budget cycles, and a series of five “cases” that represented different models for mixing desired capabilities within the constraints of the FYFP. Title Four (Planning) would lay out the chosen case, the rationale for that choice, and its expression in the form of that year’s Four-Year Defense Plan (FYDP, shortened from the older five-year model).

- The long-term planning system was the Joint Decennial Strategic Survey (JDSS), conducted early in the third year of a presidential term, at the start of its second Congress. The JDSS was designed to address, and project, global trends, issues, and objectives ten years forward from its date of release (to cover the remainder of that presidential term and the two presidential terms immediately thereafter.) The JDSS would close with three cases: the two likeliest courses for future developments over those ten years extrapolated from available information, and the “likeliest unlikely” course of development. Among their many other uses, each available JDSS would be an important resource in the development of QDRs at the start of each presidential term.

If that seems a lot to chew on, well, it is. But it'll make stuff that follows flow smoother. Roll it around the next couple or three days until the ensuing installment kicks off actual direct policy stuff, debates and politics and implementation and such.

And what will those parts look like? There are a few, in the manner of the bonus content from the late spring. (Like I say there'll be more on more subjects as we go, but right now I'm trying to just dual-track this little project and Sweet, Sweet Narrative Goodness, so other Bonus Content will have to come come along in the order of the number it pulled from that machine at the DMV. Also note that this post is likely to be the longest of the set because it introduces a substantial cast of characters and materials.)

Ahead we have

- The McGovern Defense, A Strategy of Arms: The debates and process of situating defense matters within a broader global strategy, and some of the sausage-making about how you get to the nuclear strategy/force structure baked into CART

- The McGovern Defense, Alliance or Institution?: Here we get to Curious George and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, if you will. Some ins and outs around the central front of the Cold War.

- The McGovern Defense, A Few Good Men?: Through a curious relationship between Reformers and Regulars, a military service in the throes of existential crisis (as indeed they were in the Seventies IOTL) - the United States Marine Corps - leans into change

- The McGovern Defense, All You Can Be?: Looks at the other service, besides USMC, most affected by Seventies tumult - the US Army (inclusive of its reserve components) - especially because Big Green has its own quite complex and highly dynamic Reformers-vs-Regulars phenomenon afoot inside the service itself (some of which is even touchy-feely self actualization...)

- The McGovern Defense, Military Keynesianism?: About "America's real industrial policy," ie the military-industrial complex, seen through the lens of high-dollar natsec aerospace/naval shipbuilding, plus foreign military sales. (Also a little to do with Air Force and Navy stuff directly but, when it is, very much through a defense-industrial lens, which frankly is pretty representative with those services.) And, a bit to do with those sweet summer children the McGoverner's hopes for "defense reconversion," physically changing from manufacture of swords to plowshares or the equivalent...

Fair question — currently at work trying to whip the next two (in narrative order) into publishable shape.When are you gonna get back to writing story chapters,@Yes ? Not that I mind these bonuses.

I can help with that. Good at editing. Please let me help.Fair question — currently at work trying to whip the next two (in narrative order) into publishable shape.

McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, A Strategy of Arms

A Strategy of Arms I: Thinking Big

Let's come back at it, shall we?

In the interest of not overburdening the forum's posting capacity - or the Careful Readers' stamina for single entries - I've decided to split this first post into its two distinct segments. The first deals with issues of strategy and outlook, plus the big-picture issues our McGoverners must address when they take office and go about the business of policy. That should make it somewhat the shorter of the two parts, but only by a bit. The second part deals directly with the sausage-making that goes into McGovernment policy on the employment and development of nuclear weapons, and how that fits together with the Comprehensive Arms Reduction Treaty (CART). So we'll start broad and winnow down from there into crunchy crunchy granularity.

Doesn't start much more broad than strategy - there's a centuries-old cottage industry built around defining what it even is (to include a school of thought among some analysts of strategy that "strategy" in its pure form doesn't actually exist in practice, but we'll leave that alone. No need to get dizzy hiking at altitude to start out.) In this instance, strategy has something directly to do with military action, or the deterrent threat thereof. There we could do worse than borrow Sir Basil Liddell Hart's line that strategy as it relates to warmaking and military affairs is "the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy."

That last bit carries the whole load, really - "to fulfill the ends of policy." Very often, in an American cultural and historical context, when Americans make war or threaten to make it they separate out their understanding and experience of that phenomenon from ideas about conventional politics, policy, or strategy. Then we do it over and over because, in the aggregate, Americans right up to their top-level political/policy leadership often are deeply ahistorical about military action and how it fits into a wider world of activities and experience. In the interest of a positive long term, military action - or the threat of, or capacity for - should serve strategic ends: fight now to prevent a much worse situation later, wrongfoot an adversary whose own goals might disrupt regional or world systems advantageous to you, or fight to achieve a better quality and dynamic of peace after than the one you had before. Failure to think and plan in such terms - to, instead, use war as a slugging match for will or dominance, or like a tool to fix a mechanism without a sense of cultural/political context or historical time - causes bad outcomes.

It matters, then, to define big strategic issues, possibilities, and conundrums. And sometimes different strategic visions collide - that gets us into the politics of policy. We'll see that at work here.

Let's take a moment to identify some of the issues - to do with US national security and defense policy - that any administration inaugurated in January 1973, whether that's a President Nixon or a President McGovern or, hell, even a President George Corley Wallace, would have to contend with.

Mindful that strategy is not just something you have - in order to serve its purpose strategy is also something you do - let me add another quote from McGovernment's own Jeffrey Record about how to "do" strategy, from his OTL 1988 monograph Beyond Military Reform: American Defense Dilemmas. There, Record describes strategic competence as "a willingness to make hard choices and an ability to distinguish between the desirable and the possible and between the essential and the expendable." (178)

(For those of you out there who, like me, always wonder about the pronunciation of a word I've only seen on paper/screen, Jeff Record pronounces his last name as in "record player" or "off the record." Just to clear that up. Onwards!)

Sweet Summer Children? Heroes of Reform? Both?: Roots of McGovernment Policy Culture on National Security

While the McGovern movement, and the McGovern Moment, had distinctive qualities that made it a specific thing, it grew - like its practitioners from George Himself on down - from the left-hand side of the Congressional (and mainstream American political) spectrum in the era of its birth. George personally, and many of the key figures in his administration, were a part of caucuses, informal think tanks/talking shops, webs of interpersonal relationships - within Congress, with key long-term figures of their ideological persuasion (like all those dinners at Ken Galbraith's place with other left-liberal worthies in and out of politics), in the Beltway world of think tanks and lobby outfits and revolving doors between government service and the American establishment of that era - where we can (1) situate the broad contours of how key McGoverners see the world and (2) pick out (a) things distinctive about McGovernism and (b) points of complexity and contention inside McGovernment, whether that's between different breeds/flavors of reformers or Reformers-vs-Regulars stuff, or even more complex.

Now, we can't reduce all of that to any one thing. But let's take one of the more instructive examples of that cultural/ideological/organizational context in which, and from which, McGovernite views on natsec policy and geostrategy emerged. That would be a distinctive caucus on Capitol Hill called the Members of Congress for Peace through Law.

MCPL's first life was as a bold but doomed act of egghead resistance against the political currents of the mid-Fifties, an inhospitable time when the group failed to really take root. A second pass, started in 1966 as Big Muddy over there in Southeast Asia got, well, muddier and muddier, was much more verdant and fruitful. MCPL cohered around its core outlook, issues of interest, and a smattering of institutional structure during the late Sixties, in company with Congressional criticism of the war specifically and Cold War policy more generally. But the group's real heyday was the first half of the Seventies (and a little beyond.) At that point, MCPL counted as members a little over a third of the Senate and nearly a third of the House of Representatives. Nearly all the liberals of both parties you'd expect to see in the Senate (though Cliff Case is strangely absent), with an emphasis on the Upper Midwestern liberal-to-social-democratic sorts (The Hump, Fritz, George Himself, James Abourezk, WE LOVE YOU SO DAMN MUCH PHIL, GAYLORD!, and many others) while in the House MCPL membership skewed more openly Democratic (though there were a few magnificent GOP actual-liberals like Milicent Fenwick) that also included a lot of leadership figures like Tip O'Neil, and others who you wouldn't now expect at first blush like Hale Boggs (then later his wife Lindy IOTL) and Jim Wright. By the 94th-95th Congresses IOTL MCPL had a working majority on House International Affairs, and key roles on other significant committees. It's a significant force when George decides to run for president, and if anything more so by around the Bicentennial.

What's MCPL about when it's at home? Its small educational office captures a number of the key elements in a mission statement from the period that we'll view in a different font for clarity

Substituting law for war in human society. Improving and developing institutions for just and peaceful settlement of international disputes. Strengthening the United Nations and other international institutions. Reducing world armaments. Advancing human rights and equal justice under law for all peoples. Developing a global economy where every person enjoys the material necessities of life and a reasonable opportunity for the pursuit of happiness.

There you go. Much of that explains itself in the left-liberal traditions of fighting for vibrant and functional international law, inquisitive and creative diplomacy, conflict mitigation, global equality, economic and cultural rather than military means of relationship building in North-South relations (to use a very Seventies phrase), etc. It's the broadly agreed worldview and precepts of a very active, significant caucus on the Hill at that point, one that doesn't win all its battles but that does win some, and always ensures that its interests are heard.

There are other sources to which we can look for indicative data, too. With many things McGovernment, especially at the point of first intentions, it's a good idea to look over the place where they said a lot of it first, the 1972 Democratic Party Platform that came out of the convention where George was nominated to run. Issues of geopolitics, national security, and what IR/poli sci folk call IPE (international political economy) don't show up until near the end of the document, but one gets there eventually. And what does one find once there? We'll bullet key points

This is all very much of the political/analytical milieu of MCPL and related organizations/schools of thought on the left hand of American liberalism in the early Seventies. Emphasis on coordinated, well-considered diplomacy, the centrality of the Washington-Moscow dynamic (plus the "world's largest democracy/heroic nonaligned people who invented modern non-violent protest" Indophilia that likewise affects relations with then-Peking), the friendly hand up for democratization and social justice in the Americas, the single-minded determination to end the immoral war in Southeast Asia and also the immoral regimes in Southern Africa, the growing primacy of North-South relations and an enlightened partnership with the Global South as the future of US global influence - all that stuff's baked in there. Like any platform it's aspirational, but it's also a pretty solid picture of significant policy positions, strategic interests, and matters of sheer moral determination, like an end to apartheid or getting the hell out of Big Muddy.

We can dial the focus in closer, also, to a very specifically McGovernite source document - we could really call it ur-McGovernite because it's a product of George's in-house policy wonk from his Senate office, John Holum - which is the Alternate Defense Posture read into the Congressional record by George in late January 1972. It has really strongly McGovernite qualities - by "McGovernite" here, rather than "McGovernment" I mean an ideologically and characterologically pure strain of the phenomenon close to its focal point with George Himself. I'd highlight the following characteristics though they're not the only ones of note

So, to take a very broad brush, we can suggest some significant elements of McGovernment geostrategy, or at least foreign/natsec policy outlook.

It's important to remember, however, that there may be differences over details on these points among even the most committed McGovernites, while in the rest of McGovernment there are significant actors whose views diverge on some of the specific bulleted items above.

No Plan Survives First Contact: McGovernment and Strategy Once in Office

The old saw that "no plan survives first contact with the enemy/reality" goes two ways when the McGoverners find themselves swept unexpectedly into office. They have a raft of plans and ambitions and cognitive priors/biases, sometimes with internal disagreements between specific McGoverners, that get brought to the work. At the same time, the Permanent Pentagon - especially the uniformed flag and staff officers who make the place run year in and year out - have their own perspectives on what they see as the ambitious but often naive idealism of the new crowd, and on what plans and priorities need to be laid down and followed. Both of the broadly construed sides in that relationship discover that they'll have to adapt to working together - or at least working in one another's company.

Let's take a moment before we get into all of that, to introduce two specific "uniforms" who - until their scheduled retirement in the summer of 1974 - will play quite significant roles in this early stage of grand strategizing and debate. We'll get to others too but we'll lead with these guys because of their significance to this specific thematic matter of big-picture strategy.

Keep an eye on that "bless your heart" smile

Admiral Thomas Hinman Moorer was a dentist's son from Eufaula, Alabama - though the Moorers had been a landlubbing family both Tom and his younger brother Joseph became admirals. A combat pilot in the Pacific during the Second World War, Moorer worked his way up naval aviation to command aircraft carriers and in turn both the Pacific and Atlantic Fleets - the first naval flag officer to run both. He then spent the late Sixties as Chief of Naval Operations - the uniformed head of the service - until in 1970 he became Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Moorer was a conservative in his marrow, both in the ideological and simple human dispositional sense - he was no Edwin Walker crypto-fascist, but he was an instinctual conservative, disinclined to ambiguity even though he was pretty good at institutional politics, and of the "Nixon and Kissinger have some pinko tendencies we should keep an eye on" sort (we'll get back to that in a minute.) A granular detail of note: Moorer was CNO, had just taken the job in fact, at the time of the USS Liberty incident during the Six Day War, when a US Navy listening ship was attacked methodically over a matter of hours by Israeli air and naval forces and several dozen Navy men were killed, with many more wounded. Moorer believed it was a deliberate act signed off on at a high level, not a fog-of-war incident, was incensed at the Johnson and Nixon administrations sweeping it under the rug, and IOTL remained committed to getting to the bottom of the matter for the rest of his life.

About that "pinko tendencies" thing ... Tom Moorer finds himself in a bit of a hard spot as McGovernment comes into office. Between 1969 and 1971 a Navy signals/communications guy in the White House military office, one Yeoman Charles Radford, assiduously got his hands on high-level documents that The Dick and Henry Show did not intend to share with the military establishment, either the Joint Chiefs or service-specific flag officers, and then Radford passed them on to a select group of admirals headed up by Moorer. In among the many White House tapes, Nixon - whose "Plumbers" found the leak and fingered Radford as the guilty party - called it a spy scandal outright, and decided not to go after Moorer and the other admirals publicly (1) so that it wouldn't bring the services further into disrepute and (2) for the classically Nixonian reason that he'd have kompromat, leverage, over Moorer. By 1973 rumors of the case began to reach Capitol Hill - in the McGNU as in OTL, investigative reporting will bring out more. That creates a ... complex situation for the guy most central to the uniforms' general plan to stand athwart McGovernism shouting "stop".

Eyebrows like those don't just grow themselves: Adm. Zumwalt

seen after renouncing his claim to the goblin throne in favor of David Bowie

If you want someone to do the stand-athwart-and-shout-stop stuff, though, it would be hard to find someone with more vibrant and determined energy than this guy: Adm. Elmo "Bud" Zumwalt, Moorer's successor as CNO. A surface-warfare guy who'd been a command prodigy (youngest full admiral, youngest CNO, a few other things likewise) and among other things had run the Navy's riverine "swift boat" forces in Vietnam (where his one son among a raft of daughters, who helmed a swift boat, was tragically, and in the long term fatally, poisoned by Agent Orange), on one hand Zumwalt seems like exactly the kind of senior officer McGovernment would hope for and seek to work with. And that's true so far as it goes: a liberal-minded and socially progressive guy, Zumwalt fought tenaciously against racism and sexism in the Navy, and on behalf of ordinary sailors against the service's tradition of rules and systems that were mostly designed to haze, demean, and exercise dominance over lower enlisteds. (He had a system of "Z-grams", messages to the fleets about major policy changes; the one getting rid of "the Navy way" hazing was titled "Mickey Mouse, Elimination of".) He was also an operational and technological innovator, with ideas about cheaper and from his perspective more efficient ship designs and tactics as part of the Navy's post-Vietnam renewal and modernization. A vibrant and rather charming guy, Bud grows close with George's impressionable, sweet-baby-Jesus-I-want-to-be-a-man-of-ideas Chief of Staff Gary Hart, for whom tales of low-cost hydrofoil attack boats and mini-carrier Sea Control Ships are a one-way defense reform ticket to Bonertown(TM). (Someone notify the secretarial pool ... Gare-Gare's happy to schedule Zumwalt in to talk George's ear off on occasion, which is in fact a little bewildering for a congenital Midwesterner like George.)

Remember Frank Mankiewicz's nostrum to ignore everything a politician says before the word "but"? But. In the manner of the Chiefs, Bud Zumwalt sees his role in military/natsec policy as a responsibility to fulfill a certain set of missions that he's been directed to fulfill. In his case that means, as he frames it, the need to counter and overcome growing Soviet naval power around the world, as the Red Fleet pushes its way out into blue water from that northerly Eurasian base with an ever-larger world's largest submarine force, naval-aviation bombers bristling with nuclear-tipped antiship cruise missiles, and a new generation of surface combatants. No one of such flag rank as Bud Zumwalt is as big a pessimist as Bud Zumwalt about the 1973 US Navy's ability to fulfill that geostrategic mission, one he rated in policy confabs with about a 15% chance of success. He wants more resources for the Navy, quite a bit more - specifically a "hi-low mix" fleet with a smaller critical mass of expensive, complex vessels for key roles plus a lot more cheap-but-useful ships not yet built to hunt subs and control both the high seas and naval chokepoints. Indeed Bud's quite willing to mix it up testily with the chiefs of the Army and Air Force about the distribution of total defense-budget resources being skewed towards those two services which - per Bud - shortchanges the crucial Navy role. (So much so, in fact, that fellow Navy man Tom Moorer told Zumwalt to tone it down and told Zumwalt's successor to make peace with the other services in the interests of the comity of the Chiefs.)

So in this dynamic you have

This is just by way of local flavor and dynamics for the whole of the thing. Let's get on to making some policy sausage.

The Work Starts: The Everything Review vs. The Slow Walk

Like many a newly minted presidential administration, McGovernment walks into the civilian-administered offices at DoD and launches a systemic review of organization, operational and bureaucratic practices, the all-important budgeting system/process, and of course strategy as it (strategy) governs the drawing up of force structures (that then have to be budgeted/paid for) and mission statements. This is common practice for new administrations - both the Kennedy and Nixon administrations sure did it - especially when those administrations (like Kennedy's and Nixon's) had Views about what DoD should do and how it should operate.