You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Let Them Pass

- Thread starter Geon

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Derek Pullem

Donor

That is the Tsarina's role. Wonder if some disaffected noble will try to off her?The Russian people are probably going to think Rasputin was a German puppet who undermined the Tsar.

marathag

Banned

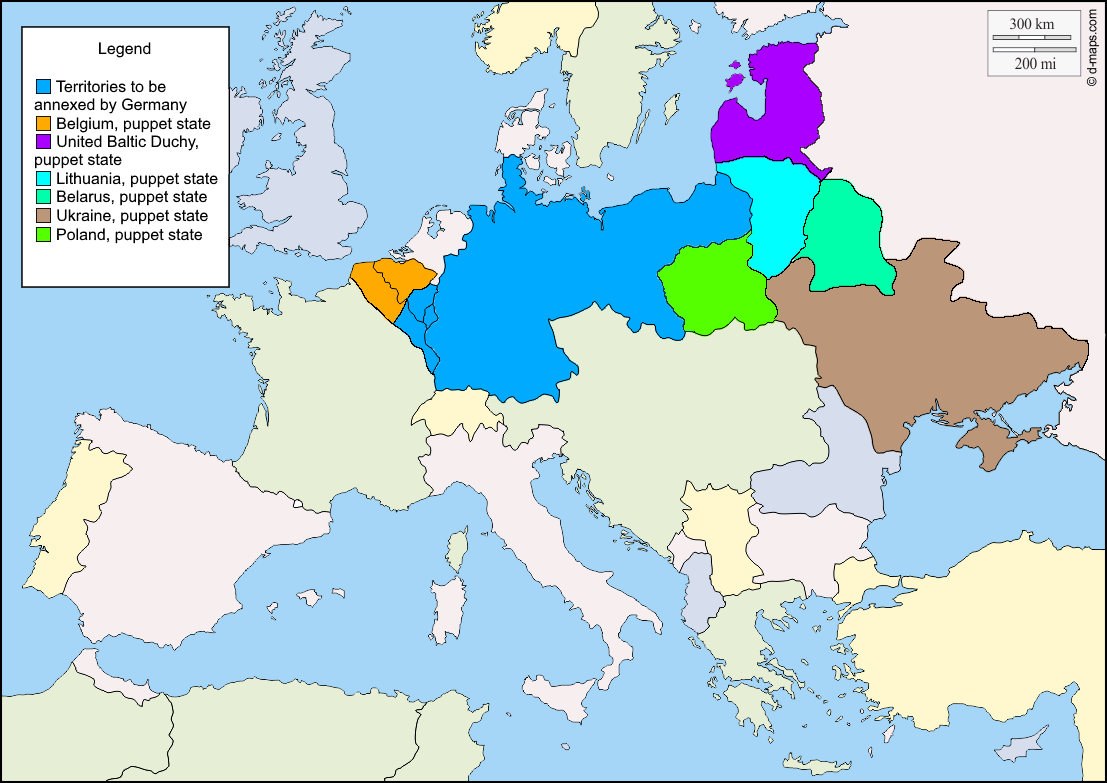

OTL after a Month of War, the September Program

this was after punching thru Belgium and the Race to Sea after Moltke's initial thrust failed, but had Hindenburg advancing in Congress Poland, while Conrad screwed up, both the Serbian and Galician attacks, with the former a rout.

This TL is different, from Germany side.

Belgium not the annoying foe.

The Idea of the Schlieffen Plan was to settle with France quickly, so the Russians could be put in their place.

So I don't see any Territory changing hands in the West, maybe some DMZ on the French Border, but in the East, I would think some form of a reconstituted Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an Independent Nation, as a buffer.

I don't see Ukraine or Byelorussia seeing much change at all

But Repartitions will be steep.

BTH, I would think the Treaty discussions would be at Grodno or Vilnius, the Germans had not yet reached so far south in September

this was after punching thru Belgium and the Race to Sea after Moltke's initial thrust failed, but had Hindenburg advancing in Congress Poland, while Conrad screwed up, both the Serbian and Galician attacks, with the former a rout.

This TL is different, from Germany side.

Belgium not the annoying foe.

The Idea of the Schlieffen Plan was to settle with France quickly, so the Russians could be put in their place.

So I don't see any Territory changing hands in the West, maybe some DMZ on the French Border, but in the East, I would think some form of a reconstituted Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an Independent Nation, as a buffer.

I don't see Ukraine or Byelorussia seeing much change at all

But Repartitions will be steep.

BTH, I would think the Treaty discussions would be at Grodno or Vilnius, the Germans had not yet reached so far south in September

In the west, I expect Luxembourg to be annexed, some level of German control over industrial parts of Northwest France (whether it is a demilitarized zone or outright annexation), and that's all I can think of really. I don't think Belgium will gain any territory either. Germany will probably sue for some colonies though. Morocco, parts of West Africa, whatever they can manage to attain. In the east similarly I don't expect much territory to change. Maybe at the very most guaranteed independence for Poland? Maybe just the Polish strip.OTL after a Month of War, the September Program

View attachment 595268

this was after punching thru Belgium and the Race to Sea after Moltke's initial thrust failed, but had Hindenburg advancing in Congress Poland, while Conrad screwed up, both the Serbian and Galician attacks, with the former a rout.

This TL is different, from Germany side.

Belgium not the annoying foe.

The Idea of the Schlieffen Plan was to settle with France quickly, so the Russians could be put in their place.

So I don't see any Territory changing hands in the West, maybe some DMZ on the French Border, but in the East, I would think some form of a reconstituted Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an Independent Nation, as a buffer.

I don't see Ukraine or Byelorussia seeing much change at all

But Repartitions will be steep.

BTH, I would think the Treaty discussions would be at Grodno or Vilnius, the Germans had not yet reached so far south in September

marathag

Banned

Realpolitik.I have hopes that Poland might gain its independence albeit they will probably have to have a government that is ''friendly'' to Germany but hey small steps.

But No Gdansk, forget right about that

The best i can see taken from Russia right as things stand right now in 1914 is Poland and Lithuania. Poland probably under a habsburg and Lithuania under a Hohenzollern (Catholic) or one of the Catholic German Dynasties (Wettin, Wittlesbach, Baden, etc).

However reparations will be steep however.

The best the Ottomans can get is Kars.

However reparations will be steep however.

The best the Ottomans can get is Kars.

He assassinates Nicholas, claims the crown for himself and marries his beloved Czarina. They live happily ever after. The end.I have something...unusual planned for Rasputin that I suspect everyone on this thread will find intriguing and interesting. You'll see it in a few chapters.

Derek Pullem

Donor

I'm not sure the September Program is really a blueprint for a peace deal - I'd see it more as a document analogous to the "Project for a New American Century" that was produced by the US Neo-Cons in the aftermath of the fall of communism. Aspiration not concrete plan.

Monitor

Donor

It is mostly that. That was a group that sat down, and then build a wishlist of as many factions as possible. There were never plans to put it into place in its entirety (also, parts of it are countering each other, so there is that as well...)I'm not sure the September Program is really a blueprint for a peace deal - I'd see it more as a document analogous to the "Project for a New American Century" that was produced by the US Neo-Cons in the aftermath of the fall of communism. Aspiration not concrete plan.

It is a great guideline, and the only we have, because Germany decided that war goals are not important, but that was the wishlist that would have perhaps been used, if the battle of the Marne was a victory, the British fleet decided that it looks significantly better underwater, and the Russia capitulates before Christmas without conditions.

Derek Pullem

Donor

I would have thought a Wettin Polish Grand Duchy under the Crown Prince of Saxony would be a good starting point - historical links to Poland and he's definitely Catholic - he became a Jesuit priest after his fathers abdication! Not convinced A-H will have a big say in the peace negotiations. Not sure how much of the Baltics / Lithuania Germany will be able to squeeze out of Russia - it may just be an enlarged CourlandThe best i can see taken from Russia right as things stand right now in 1914 is Poland and Lithuania. Poland probably under a habsburg and Lithuania under a Hohenzollern (Catholic) or one of the Catholic German Dynasties (Wettin, Wittlesbach, Baden, etc).

However reparations will be steep however.

The best the Ottomans can get is Kars.

I would point out everything has happened so quickly that the Ottomans have not even joined the war yet so unsure if they would even get anythingThe best the Ottomans can get is Kars.

and right i quite forgot!I would point out everything has happened so quickly that the Ottomans have not even joined the war yet so unsure if they would even get anything

Geon

Donor

Rasputin has been portrayed as an evil manipulative villain down through the ages. However, what little I have researched on the man reveals a much more complex individual. He believed himself a holy man - as did many around him - yet lived a very libertine lifestyle. He was a very complex man. Contrary to what some people said of him he was not the devil incarnate.He assassinates Nicholas, claims the crown for himself and marries his beloved Czarina. They live happily ever after. The end.

I would point out everything has happened so quickly that the Ottomans have not even joined the war yet so unsure if they would even get anything

The Ottomans are in a curious position.

I assume, since @Geon has not said otherwise, that Admiral Souchon made his run for the straits successfully.

Now, you would think that a war that has turned badly against the Entente would make belligerency on behalf of the Central Powers even more enticing. But on the other hand, a Britain which has left the Western Front has plenty of resources to spare to not just blockade but also invade Turkish domains.

Of course, this assumes that the war has not ended before the Turks have a chance to jump in . . .

Perhaps the Sublime Porte might explore the possibility of declaring war ONLY on the Russians?

The best i can see taken from Russia right as things stand right now in 1914 is Poland and Lithuania. Poland probably under a habsburg and Lithuania under a Hohenzollern (Catholic) or one of the Catholic German Dynasties (Wettin, Wittlesbach, Baden, etc).

However reparations will be steep however.

I would have thought a Wettin Polish Grand Duchy under the Crown Prince of Saxony would be a good starting point - historical links to Poland and he's definitely Catholic - he became a Jesuit priest after his fathers abdication! Not convinced A-H will have a big say in the peace negotiations. Not sure how much of the Baltics / Lithuania Germany will be able to squeeze out of Russia - it may just be an enlarged Courland

In OTL, of course, the nod ended up going to a Habsburg: Archduke Karl Stephan.

My sense is that the earlier the war ends and the earlier the Polish state is set up, it is more likely to go to a Habsburg - even if a lot of Vienna's leverage was diminished after the disaster in Galicia in 1914.

On the other hand, the longer the war goes on, the greater will be the German appetite: It will have suffered more loss of blood and treasure, AND it will be sitting on ever more Russian territory. With France closed out (and all the troops that frees up to head East), it is hard to see the Germans NOT securing Riga and possibly even Minsk by the following summer (along with having cleard Galicia). This has them holding not just all of Poland, but also Lithuania, Courland, and a growing slice of White Russia by the next summer.

Which raises the question of just what the Germans will want, and what they will want to do with it. Do they demand the so-called "Polish Border Strip?" Or do they focus their appetites up in the Baltics? Or both? Here is some interesting background I unearthed - I apologize for the length of the quote, but I think it is quite valuable to highlight - on German thnking as it evolved in 1914-16:

The first wartime number of the AfiK, in August 1914, contained the article “Inner Colonization and the War,” by the editor Erich Keup. For now, explained Keup, the work of inner colonization had been “laid still.” Yet, inner colonizers could be proud that they had already provided Germany with many new “diligent farmers” (kernige Bauern), “first class material for hard war work.” Crucially, with an eye toward picking up where they left off when this short war was over, Keup described German land as “somewhat still thinly settled” (teilweise noch duenn besiedelte). That is, Lebensraum within Germany still clearly existed for these thinkers. Keup went on to boost the inner colonization argument by indicating how “lucky” Germany was that the 300,000 Russians and 200,000 Galicians upon whom they still depended for farm labor had already brought in most of the harvest by the outbreak of war, thus highlighting how dangerous it was to rely on foreign labor. This sobering fact, along with the current, but surely not last, Slavic storming of Germany, led Keup to demand that efforts be stepped up postwar to thicken Germany’s East with more German farmers. He was sure, however, that the expe-rience of the war would place inner colonization front and center in postwar politics.

As late as the January 1915 edition of the AfiK there continued to be serious talk of inner colonization inside the German borders. One author demanded that reparations after the war be used to help settlers, and he then continued to vent against the Junker, naming them as the chief reason for peasant flight from the land. The author invoked Sering who had argued continually that wherever there are Junker, there is flight from the land, wherever small holdings, one finds an increase in population. Thus, it was still recognized that a colonial future in the East inevitably meant negotiating with German land holders, the ultimate goal being the fill-ing of space inside Germany. In the latter vein, Keup this time wrote about the recently liberated areas of East Prussia, and argued that because the land there was so thinly settled, it had been that much easier for the Russians to completely “desertify” (verwüsten) the land. The province, however, was now ready for intensive settlement, and in a slightly biolog-ical turn in Keup’s language, he argued that a “new race” was to be “planted on the verwüstet soil,” and that only this new “wall” of farmers could save Germany from a future Slavic invasion.

Indeed, the idea of a future buffer zone, the emptying of the eastern borderlands of Poles and Jews and filling it with Germans, was famously discussed at the highest levels of government, beginning in late 1914. As Fritz Fischer and Immanuel Geiss explained some 40 years ago, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg under the cover of war sought radical solutions to the Polish problem, and secretly contacted several thinkers about their ideas concerning the creation of Grenzstreifen, or “frontier strips,” cleansed of undesirable populations. The idea to be developed was the creation of a stretch of land just east of West Prussia and Posen, which would be denuded of its Polish and Jewish populations, and filled with Reich Germans as well as Germans returning from the East (Deutsch-Russen). By creating a ring of Germanness around the Prussian Poles, cutting them off from their east-ern neighbors, it was believed that they would eventually fully assimilate. What is so crucial is to whom Bethmann-Hollweg turned, who exactly the chancellor of Germany considered to be the “experts” for such thinking, who he considered his Ostexperten. He asked the “thinkers” of inner colonization, the authors who often appeared in the pages of the AfiK. A frequent contributor to the Af iK, the Oberpräsident of East Prussia, Batocki, indicated he somewhat liked the idea, but balked at the removal of all Poles (a realistic nod to his Junkerbackers). A key member of the GFK, Alfred Hugenberg was the most extreme in his views, desiring a cleared racial space, and pressing home the older inner colonization argument that only through such a clearing would Germans be “forced” back onto the land, and by doing so, would save the fatherland from becoming a weak, urban people with a low birthrate. The president of the GFK, Friedrich von Schwerin, was very keen, encouraging the chancellor to kick out every last Pole and bring in the Germans. And according to Geiss, Schwerin’s two elaborate proposals, cowritten by the AfiK editor Keup, in March and December 1915, became the basic documents upon which all further discussion of eastern settlement at the highest levels was discussed. As for the godfather of the movement, Max Sering, his mission for the government was to be much more concrete and substantial. First, though, the colonial space of the East had to be captured and secured, and it was.

During the Great Advance of 1915, beginning in May and only petering out in late September, the German Army captured a vast new empire in Eastern Europe. Shortly before the massive offensive began, though, a crucial shift occurred in the articles of the AfiK. The February 1915 edi-tion contained the article “New Paths of German Colonial Politics.” Over the past several years, the author argued, Germany had increasingly become a colonial power, but it had been a colonialism that sought worldwide influence instead of territory. This focus was deemed incorrect by the author, for among other things, such a business-oriented policy created an industry-heavy, and thus weaker German people. Further, this colonial policy forced Germany to rely on other nations, and it had done nothing to alleviate the problem of overpopulation in Germany. Then came the key shift in inner colonial thinking: the author stated “even if all the swamps in Germany were drained, there wouldn’t be enough land in the Reich to grow all the food we need, and to settle all the people we must settle in order to have a healthy mix of both an industrial and farmer state” (gesunde Mischung von Industrie- und Bauernstaat). Quite suddenly then, in the early 1915 editions of the AfiK, Germany transformed from a land still empty, to a land now full. The author then introduced the idea of “Aussiedlung,” settlement outside the Reich, in the pages of this “inner colonial” journal. The Romans did it, he claimed, as did the Franks. But in an example of racial thinking beginning to enter the discourse of the AfiK, he pointed out that while the Teutons practiced Aussiedlung right in the same area now under discussion, their “national” feelings were on the wane in that period and they indulged in intermarriage with the Slavs. Thus, and clearly picking up on the “border strip” discussions going on, the author stated that, if Germany won new land in the East, it was to be emptied of all “inferior” (minderwertig), untrustworthy populations. Allowing them to stay would lead to an “unhealthiness” (Unheil) and a mixing that would result in racial “deterioration” (Verschlechterung). The author stated that other great powers did such things, and that, in fact, forced transfers of population had now been rendered internationally legal due to the peace of Bucharest in 1913. The author admitted that while the reader might ask, “is this fair,” he responded, was it fair what the Russians did in East Prussia? In other words, here in the radicalized moment of war, anything could be rationalized. Finally, the author claimed that the implementation of such a program of settlement had now been made much easier due to all of the tools provided by the program of inner colonization.

This same article contained a long footnote by the editorial board claiming that such language was not unacceptable, and that it had indeed appeared in other publications in Germany. As further proof, in the very same edition, for the first time AfiK printed an article from the Pan-German Alldeutsche Blätter. In “Russians on Northwest Russia as a German Settlement Territory,” the author stated that many Russians already understand that Western Russia is the proper German colonial area. Further, once the area is controlled by Germany, 100,000 Ruthenians a year will be shipped from there to Siberia. The AfiK editorial team then simply added that they hoped this article was correct. In the April 1915 issue, Keup provided a list of all the important people and publications that were now calling for “new land.” In this same piece, he alluded to what was surely on the minds of the veteran inner colonization thinkers: the acquisition of new land in the East would finally transcend the endless and frustrating battle with the Junker. Much more direct articles discussing exactly how and where to begin this “outer” colonization, namely, in the Baltics, were put forward in pieces by the Baltic German Silvio Broedrich. By January 1916, none other than Ludendorff was consulting with Schwerin about German settlement opportunities in his military colony, Ober Ost, in Lithuania. Finally, it was throughout this period that, under the radar, the doyen of inner colonization was sent on a mission to the East. Traveling through Poland in September 1915, Sering decided that that entire country was also too full for settlement. It was only in Lithuania and Courland that Sering, the “moderate” inner colonial thinker, saw Germany’s future, and there drew up plans for the eventual settlement of 1.5 million German colonists in that “empty” land.

Running in tandem with this radicalization of the idea of legitimate colonial space in the AfiK, the earlier social colonization theme took flight. Referring to the earlier work of inner colonization in getting workers onto the land, a series of articles in mid-1915 came out in favor of using those same organizational skills to provide land for, and help settle, war invalids. “All that we’ve learned will help Germany in this endeavor” claimed Keup, and obvi-ously, “the land is the best place for them, for their health, and for Germany." Here, and in proceeding articles, inner colonial thinkers made clear their expertise, as they easily waded through the vast legal and monetary issues that would accompany such a program. And they could move quickly: on May 7, 1915, a request to settle war invalids was officially made to the Reichstag, signed by many of the inner colonial gang. For the latter half of 1915, this theme dominated the AfiK.

"Inner Colonization and Soldier Homes,” appearing in early 1916, reviewed the importance of settling invalids, highlighting the plight of the veterans of 1871 who had found such a proposition personally too costly. This time, argued the author, those involved in inner colonization were going to make such settlement cheaper and easier. However, stated the author, it was fascinating that until this war people like him never even thought of the land to the east of the German border. They had been happy with their piece of the planet, he continued, but now that so much German blood had been spilt, returning warriors would find lots of room in the land Germany was now securing in the East. Indeed, Sering’s findings with regard to settlement in Courland were published in October 1916, and Broedrich pushed this plan in the AfiK throughout the year. Specifically, Broedrich emphasized how “cheap” the land was for settlers in the Baltic region, clearly an appeal to those who were sick of the ever-rising price of land in West Prussia and Posen. In an article asking for more money from the government to facili-tate settlement, Schwerin argued that settling “war cripples” in the East was not going to result in any great empire. It was time to move well past war invalid settling, he declared, and instead talk about getting Germans in tototo start heading east. Couching these straightforwardly imperialistic calls were a steady stream of atrocity articles going on about how the Russians treated so-called Deutsch-Russen, Germans who had lived for many years in Russia. This was obviously an attempt to justify Germany as the only correct imperial power for East Central Europe.

It's interesting to see how the thinking of Sering shifted here once he went out on the ground and looked over the territories in question (which makes you wonder just what he really knew before the war when he was cooking up his map of annexations). And he is a very important figure, along with Keup: these were the men Bethmann-Hollweg turned to in formulation of German policy in the East (before Ludendorff basically took over the show in 1916). Likewise, it is also fascinating to see how quickly the war radicalized German leadership on these questions; the longer it went on, the more radical their aims seemed to become. A war that ends earlier has to take account of that.

Complete article here. Nelson, Robert L. 2009b. “The Archive for Inner Colonization, the German East, and World War I.” In Germans, Poland, and Colonial Expansion to the East: 1850 Through the Present, edited by Robert L Nelson, 65–93. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Last edited:

Russia has sued for peace, there is no war anymore at least not active so I do not see any country jumping in. Keep in mind it is still September and all that remains is negotiations.The Ottomans are in a curious position.

I assume, since @Geon has not said otherwise, that Admiral Souchon made his run for the straits successfully.

Now, you would think that a war that has turned badly against the Entente would make belligerency on behalf of the Central Powers even more enticing. But on the other hand, a Britain which has left the Western Front has plenty of resources to spare to not just blockade but also invade Turkish domains.

Of course, this assumes that the war has not ended before the Turks have a chance to jump in . . .

Perhaps the Sublime Porte might explore the possibility of declaring war ONLY on the Russians?

Chapter 35: The Eastern Armistice and the View from Berlin

Geon

Donor

Speaking of negotiations.

----------------------------------------

The armistice for the Eastern Front was signed by representatives of Imperial Russia, The German Empire, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire on October 3rd, 1914. Two days later the armistice took effect at 10 A.M. It essentially mandated a cease-fire in place until a peace agreement was reached.

The war, which would soon be called The Great European War (a misleading name given that fighting was still occurring at the time of the two armistices in both Africa and the Pacific) was over and the Central Powers were the clear victors.

Yet victory brought its own problems. As Kaiser Wilhelm would declare to his Cabinet and the General Staff, “It is one thing for us to win the war, it is another for us to win the peace that follows.”

There were some on the General Staff who wanted to send German troops to the Pacific to deal with the Japanese siege of Tsingtao. However, the Kaiser had quickly squelched that idea. With General Hindenburg’s backing the Kaiser explained to the Generals and Cabinet. “If you will recall back in 1905 at the height of the Russo-Japanese War the Russians too tried to “deal” with the Japanese siege of Port Arthur by sending a substantial portion of their navy to the Pacific. I trust gentlemen you all remember that bit of comic tragedy which concluded with the Battle of the Tsushima Straits? I should not want that performance repeated with Germany in the starring role this time. Better to let the conference room be our battleground.”

It was also noted by Foreign Minister, Gottlieb von Jagow, that Germany needed to tread lightly in her demands. Yes, she had won a decisive victory in both the West and the East. What she did not want was a repeat of this same situation to occur perhaps in ten or twenty years. A vengeful France in the West and Russia in the East would almost certainly ensure another war.

The Belgian Acquiescence had allowed the Germans a quick victory in the West which had assured an equally quick victory in the East. But that could not be relied upon a second time. “We have had a small taste of what could have been a catastrophic war for not only Germany but the rest of Europe,” proclaimed von Jagow. “Our demands should be mild as possible. Otherwise, the next war will be even worse.”

This of course brought an angry response from General Ludendorff. “Thousands of German young men are dead and thousands more wounded because of this war. The German people will not be content with simply having our troops march home proclaiming victory with nothing to show for that victory.”

“I agree,” the Kaiser replied. “But if we are too punitive, we are, as Foreign Minister von Jagow points out virtually guaranteeing another possibly more terrible war in our future.”

After a moment’s thought Kaiser Wilhelm said, “We need a peace plan that will assure us not of a few years of peace but of perhaps a generation of peace.”

A series of committees were therefore set up to draw up terms Germany would accept. Then telegrams were sent out to London, Lyons, St. Petersburg, Vienna, Rome, Istanbul, Belgrade, and Tokyo. Even neutral nations were invited to ascertain their views and desires.

What would be known as the Berlin Conference would be held in November, beginning on November 14th.

----------------------------------------

Chapter 35: The Eastern Armistice and the View from Berlin

The armistice for the Eastern Front was signed by representatives of Imperial Russia, The German Empire, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire on October 3rd, 1914. Two days later the armistice took effect at 10 A.M. It essentially mandated a cease-fire in place until a peace agreement was reached.

The war, which would soon be called The Great European War (a misleading name given that fighting was still occurring at the time of the two armistices in both Africa and the Pacific) was over and the Central Powers were the clear victors.

Yet victory brought its own problems. As Kaiser Wilhelm would declare to his Cabinet and the General Staff, “It is one thing for us to win the war, it is another for us to win the peace that follows.”

There were some on the General Staff who wanted to send German troops to the Pacific to deal with the Japanese siege of Tsingtao. However, the Kaiser had quickly squelched that idea. With General Hindenburg’s backing the Kaiser explained to the Generals and Cabinet. “If you will recall back in 1905 at the height of the Russo-Japanese War the Russians too tried to “deal” with the Japanese siege of Port Arthur by sending a substantial portion of their navy to the Pacific. I trust gentlemen you all remember that bit of comic tragedy which concluded with the Battle of the Tsushima Straits? I should not want that performance repeated with Germany in the starring role this time. Better to let the conference room be our battleground.”

It was also noted by Foreign Minister, Gottlieb von Jagow, that Germany needed to tread lightly in her demands. Yes, she had won a decisive victory in both the West and the East. What she did not want was a repeat of this same situation to occur perhaps in ten or twenty years. A vengeful France in the West and Russia in the East would almost certainly ensure another war.

The Belgian Acquiescence had allowed the Germans a quick victory in the West which had assured an equally quick victory in the East. But that could not be relied upon a second time. “We have had a small taste of what could have been a catastrophic war for not only Germany but the rest of Europe,” proclaimed von Jagow. “Our demands should be mild as possible. Otherwise, the next war will be even worse.”

This of course brought an angry response from General Ludendorff. “Thousands of German young men are dead and thousands more wounded because of this war. The German people will not be content with simply having our troops march home proclaiming victory with nothing to show for that victory.”

“I agree,” the Kaiser replied. “But if we are too punitive, we are, as Foreign Minister von Jagow points out virtually guaranteeing another possibly more terrible war in our future.”

After a moment’s thought Kaiser Wilhelm said, “We need a peace plan that will assure us not of a few years of peace but of perhaps a generation of peace.”

A series of committees were therefore set up to draw up terms Germany would accept. Then telegrams were sent out to London, Lyons, St. Petersburg, Vienna, Rome, Istanbul, Belgrade, and Tokyo. Even neutral nations were invited to ascertain their views and desires.

What would be known as the Berlin Conference would be held in November, beginning on November 14th.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: