Hecatee

Donor

Tabularium, Rome, november 177

Five years ago Titus Manlius Caledonius was a centurion on duty on the Rhenus border, where he used his free time playing with large tablets to see if numbers could help him better manage his unit. Now he was a member of the equestrian order, and a centenarii in the imperial treasury administration, in charge of fraud control. Working from historical data, he’d built tables of provincial revenues that allowed the administration to detect variations in incomes and predict future revenues by looking at the parameters that influenced it.

He had been promoted to the position three years before and he’d immediately started to ask for historical information on grain production, tax incomes and similar topics, making great tables of information for each province for each year of the past century. Some of the information was available from the regular census data, other he’d had to ask to local administrations, which had taken their own sweet time to answer until an order from the Emperor himself had made sure to shorten any delay. He’d then made great tables summarizing the information for each province, and then put together large summaries for the empire. This had taken two years before he could show true results…

Working with great mathematicians working at the Academia and at Trajan’s library in the forum Trajanus, he’d begun to identify patterns, and from there irregularities, a number of them turning out on further examination to be frauds. Some were known, other not : soon the first few trials were started in court where his information proved accurate and large sums of ill gotten gains retrieved for the state.

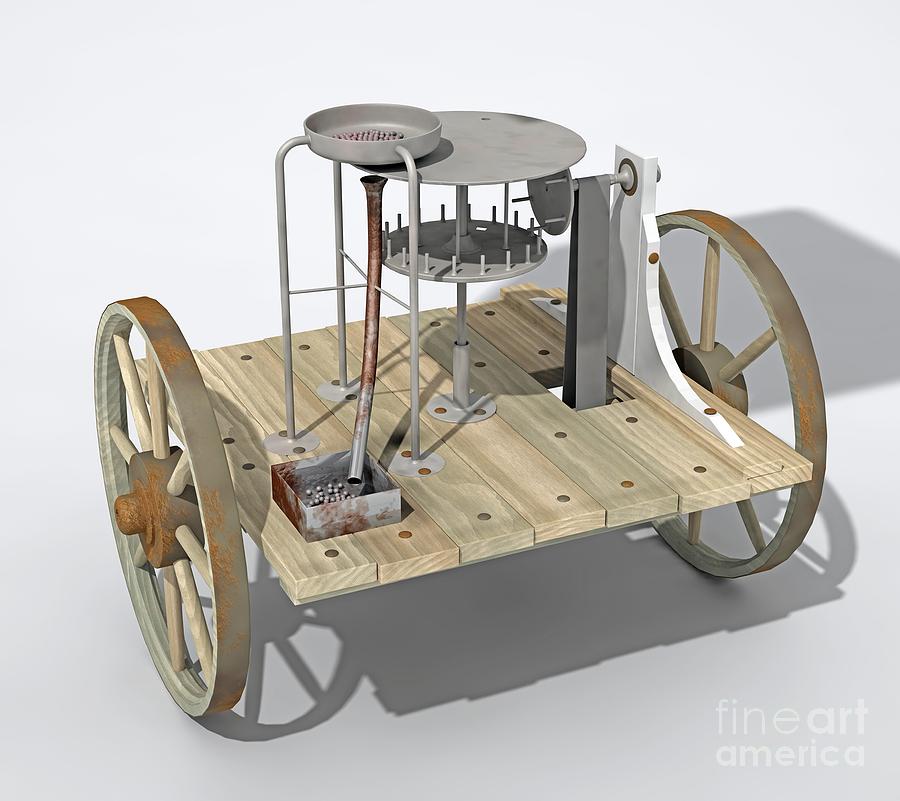

Now Manlius Caledonius was in his office talking with a machinatorum, a bronze device sitting on the table between them : “So you tell me this tabullator is able to do common mathematical operations and display the result, whether this operation is an addition, a soustraction, a multiplication or a division ?” asked the official to the engineer.

“Yes it is. It is actually the second generation of calculating machine. At first I used simple disks but it proved to be unsatisfactory for multiplications and divisions. But a colleague of mine had a brilliant idea, making cylinders with teeth of variable height and this led me to build the contraption you now see.”

“I must say it is most unusual to look at, although not unpleasant to see.”

“Well I’ve seen machines both in Alexandria and in some collections here in Rome, including the Emperor’s, that gave me a lot of ideas. There is also research coming from Alexandria that inspired me, including a mechanical horologium that a colleague invented a year ago and which has been described to me in great details by a friend that was coming back from an assignment in Egypt. We still meet a lot of issues with gears and cogs but when one decides to look into them one never knows what he’ll be able to achieve…”

“Well we shall see if it is as interesting and useful as we expect it to be. As you can see I’ve had a table of information brought, from which a number of calculations can be made. Hirtius here is one of my best employee, he has not worked on the calculations our service made from this table so he’ll start from the same point you do although I do have all the result double checked and copied on this papyrus. We’ll see if your machine is faster and provides correct answers !”

“I’m glad for the challenge !”

--

Three hours later Hirtius put his pen down on the table, his calculations finished. The machinatorum had already turned in his results quite some time before, allowing Manlius Caledonius to check them against the information he’d been provided with. He took a few minutes to check the results of his clerk and smiled before turning toward the two men :

“Well it seems the Academia has once more delivered a miracle ! Prefect Prigonus will certainly be most happy that his institution has once more delivered. Not only did the result come very fast but it was also correct. You Hirtius must not be disappointed though for your calculations were correct and none in the departement could have done them better. We’ll need to do some more tests on the machine to ensure it is indeed as good as we expect it to be, but I think we’ll soon order a number of them. In fact every provincial or local administration should have at least one of those machines !”

-----

The machine discussed is a Leibnitz type of calculator, itself a late 17th century improved version of the Pascaline invented earlier that century by French philosopher Blaise Pascal

Five years ago Titus Manlius Caledonius was a centurion on duty on the Rhenus border, where he used his free time playing with large tablets to see if numbers could help him better manage his unit. Now he was a member of the equestrian order, and a centenarii in the imperial treasury administration, in charge of fraud control. Working from historical data, he’d built tables of provincial revenues that allowed the administration to detect variations in incomes and predict future revenues by looking at the parameters that influenced it.

He had been promoted to the position three years before and he’d immediately started to ask for historical information on grain production, tax incomes and similar topics, making great tables of information for each province for each year of the past century. Some of the information was available from the regular census data, other he’d had to ask to local administrations, which had taken their own sweet time to answer until an order from the Emperor himself had made sure to shorten any delay. He’d then made great tables summarizing the information for each province, and then put together large summaries for the empire. This had taken two years before he could show true results…

Working with great mathematicians working at the Academia and at Trajan’s library in the forum Trajanus, he’d begun to identify patterns, and from there irregularities, a number of them turning out on further examination to be frauds. Some were known, other not : soon the first few trials were started in court where his information proved accurate and large sums of ill gotten gains retrieved for the state.

Now Manlius Caledonius was in his office talking with a machinatorum, a bronze device sitting on the table between them : “So you tell me this tabullator is able to do common mathematical operations and display the result, whether this operation is an addition, a soustraction, a multiplication or a division ?” asked the official to the engineer.

“Yes it is. It is actually the second generation of calculating machine. At first I used simple disks but it proved to be unsatisfactory for multiplications and divisions. But a colleague of mine had a brilliant idea, making cylinders with teeth of variable height and this led me to build the contraption you now see.”

“I must say it is most unusual to look at, although not unpleasant to see.”

“Well I’ve seen machines both in Alexandria and in some collections here in Rome, including the Emperor’s, that gave me a lot of ideas. There is also research coming from Alexandria that inspired me, including a mechanical horologium that a colleague invented a year ago and which has been described to me in great details by a friend that was coming back from an assignment in Egypt. We still meet a lot of issues with gears and cogs but when one decides to look into them one never knows what he’ll be able to achieve…”

“Well we shall see if it is as interesting and useful as we expect it to be. As you can see I’ve had a table of information brought, from which a number of calculations can be made. Hirtius here is one of my best employee, he has not worked on the calculations our service made from this table so he’ll start from the same point you do although I do have all the result double checked and copied on this papyrus. We’ll see if your machine is faster and provides correct answers !”

“I’m glad for the challenge !”

--

Three hours later Hirtius put his pen down on the table, his calculations finished. The machinatorum had already turned in his results quite some time before, allowing Manlius Caledonius to check them against the information he’d been provided with. He took a few minutes to check the results of his clerk and smiled before turning toward the two men :

“Well it seems the Academia has once more delivered a miracle ! Prefect Prigonus will certainly be most happy that his institution has once more delivered. Not only did the result come very fast but it was also correct. You Hirtius must not be disappointed though for your calculations were correct and none in the departement could have done them better. We’ll need to do some more tests on the machine to ensure it is indeed as good as we expect it to be, but I think we’ll soon order a number of them. In fact every provincial or local administration should have at least one of those machines !”

-----

The machine discussed is a Leibnitz type of calculator, itself a late 17th century improved version of the Pascaline invented earlier that century by French philosopher Blaise Pascal