Hecatee

Donor

Syria, autumn 117 CE

As tired as Publius Aelius Hadrianus Buccellanus might be, he knows his day is far from over. He has just finished a tense meeting with his concilium, during which the fate of Lusius Quietus, the untrustworthy legate of Judea, has been sealed. With the orders sent earlier to Publius Acilius Attianus, the præfectus prætorio, Hadrianus is confident that his rule will not be challenged in the immediate future. This only leaves the question of what to do for the long term destiny of the imperium.

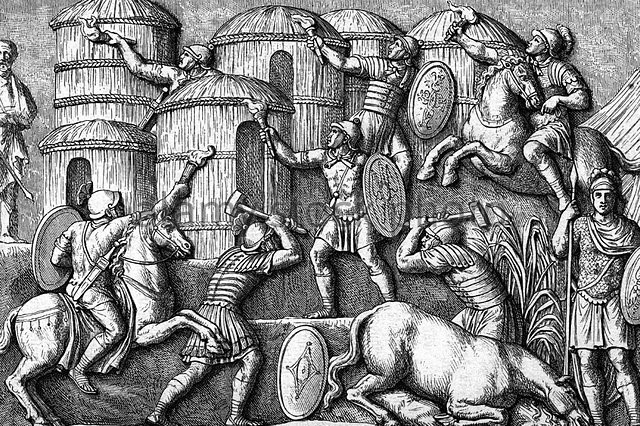

For now peace has been restored in the East. The Parthian have been severely beaten, their armies shattered, numerous cities taken and plundered, some like Edessa having been razed to their foundations. The Jewish revolts in Judea and in various other cities of the empire have also been crushed, with many of those blasphemous deniers of the gods killed by the legions or the regional authorities. Quietus, before his fall, raised a statue of Hadrianus on the ruins of the Jews’ temple of Hierosolyma.

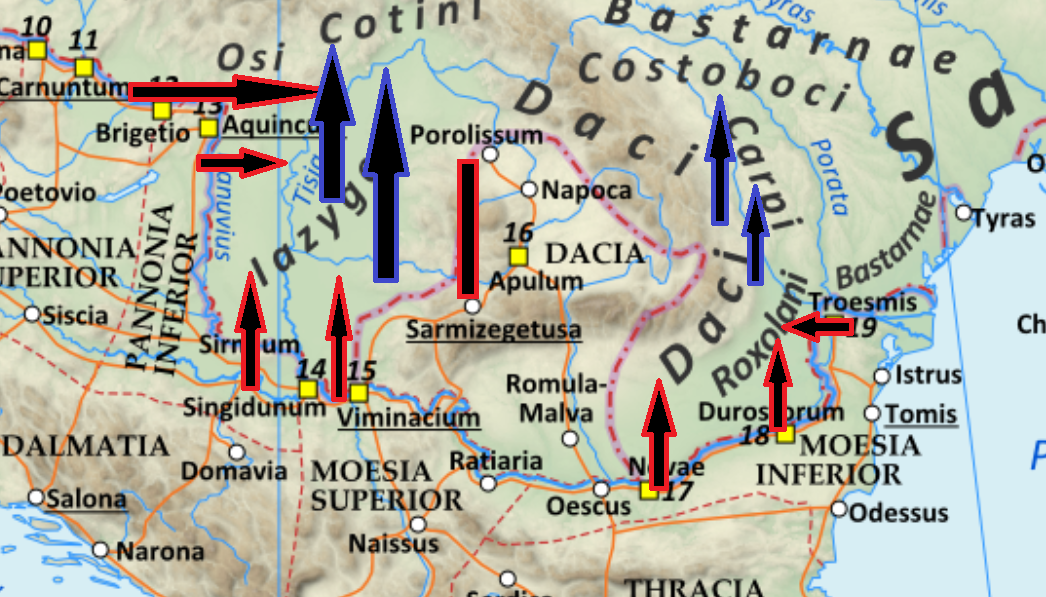

But peace is always fragile. The conquest of Dacia is still fresh, and the land is dangerously exposed to the barbarian threat. And there are so many other areas at risk from a barbarian invasion... Britannia, of course, is still partly free. Germania, as always, is a threat. Plenty of parts of the Danubian border are wide open to raids or even outright invasion, as he well knows since he did recently survey them in the name of the late imperator Trajanus.

Augustus, be he blessed in his eternal glory, had said that the Empire’s borders were to be secured, conquest was to be shunned. Well, that had not been the vision of Trajanus, conqueror of Dacia and of Parthia… But would it be his policy ? He had already ordered a withdrawal from many part of the newly conquered territories, too insecure with their rear in full revolt. This has bought him time but also the enmity of many in the army. But should he do more ? Fortify what fronts he can, abandon what land he cannot hold ?

A cup of wine in his hand, the emperor loose himself in his thoughts before finally falling asleep from the wine and the exhaustion, but not without taking some decisions first…

As tired as Publius Aelius Hadrianus Buccellanus might be, he knows his day is far from over. He has just finished a tense meeting with his concilium, during which the fate of Lusius Quietus, the untrustworthy legate of Judea, has been sealed. With the orders sent earlier to Publius Acilius Attianus, the præfectus prætorio, Hadrianus is confident that his rule will not be challenged in the immediate future. This only leaves the question of what to do for the long term destiny of the imperium.

For now peace has been restored in the East. The Parthian have been severely beaten, their armies shattered, numerous cities taken and plundered, some like Edessa having been razed to their foundations. The Jewish revolts in Judea and in various other cities of the empire have also been crushed, with many of those blasphemous deniers of the gods killed by the legions or the regional authorities. Quietus, before his fall, raised a statue of Hadrianus on the ruins of the Jews’ temple of Hierosolyma.

But peace is always fragile. The conquest of Dacia is still fresh, and the land is dangerously exposed to the barbarian threat. And there are so many other areas at risk from a barbarian invasion... Britannia, of course, is still partly free. Germania, as always, is a threat. Plenty of parts of the Danubian border are wide open to raids or even outright invasion, as he well knows since he did recently survey them in the name of the late imperator Trajanus.

Augustus, be he blessed in his eternal glory, had said that the Empire’s borders were to be secured, conquest was to be shunned. Well, that had not been the vision of Trajanus, conqueror of Dacia and of Parthia… But would it be his policy ? He had already ordered a withdrawal from many part of the newly conquered territories, too insecure with their rear in full revolt. This has bought him time but also the enmity of many in the army. But should he do more ? Fortify what fronts he can, abandon what land he cannot hold ?

A cup of wine in his hand, the emperor loose himself in his thoughts before finally falling asleep from the wine and the exhaustion, but not without taking some decisions first…