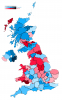

Are the colors reversed on the map? The way it currently looks appears to have Northern Ireland voting heavily republican and much of Wales voting for the monarchy, which is the opposite of what was described.View attachment 594014

The 1946 British institutional referendum was held on the 7th March 1946 to determine whether the United Kingdom would retain its monarchy or abolish the institution and become a republic. The referendum had been one of the policy planks of Clement Attlee’s Labour government, in response to the opposition of many of the party’s members to the behaviour of King Edward VIII since he ascended to the throne in 1936.

Republicanism had been growing in strength in Britain since the ascension of King Edward VIII to the throne in 1936, as he became the centre of controversy over his courtship of an American divorcee, Wallis Simpson. While he wished to marry Simpson, the opposition of the prime ministers of the UK and the Dominions (and the possibility of the British government resigning and a general election being forced) meant his aides cut communications between him and Simpson and forced him to remain King.

This ultimately proved extremely detrimental to both Edward (who was reportedly greatly depressed by these actions) and the British public, and Edward’s association with the ‘Cliveden set’, a group of upper-class socialites who favoured cooperation with Nazi Germany, made him and the monarchy deeply unpopular with Britons, particularly when World War II started in 1939.

Once Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940 and Britain cracked down on pro-Axis sentiment among the public, Edward became silent on the issue, but many people still believed him to be staying quiet out of fear of punishment by the government and not because he genuinely opposed Nazism. He also seemed to show little solidarity with the British public during the Blitz, and many were suspicious of the Nazis’ decision to bomb the House of Commons, but not Buckingham Palace.

The conditions of the referendum (such as the wording of the question- “Should the United Kingdom become a republic or remain a monarchy?”- and the date) were agreed during the early months of the Attlee government in mid-to-late 1945, and it was decided for the sake of civility that both Attlee and Edward would remain publicly neutral and would not partake in campaigning.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the referendum proved heavily partisan, as Labour voters overwhelmingly favoured the republic option and Conservatives and Unionists advocated for the monarchy; there were even reports of voter suppression in Northern Ireland, where over 81% of the vote went to the monarchy option and 96% of voters in County Down voted for the monarchy, more than any other county in the country.

Despite this, public sympathy for the royal family was extremely low, and leftist Labour politicians such as Nye Bevan and Stafford Cripps stressed that the tax breaks offered to the royals and the upkeep of their property could be put into policy programmes which would benefit the public.

By far the most vociferous opponent of the republican side was, surprisingly, not the major leaders of the Opposition Churchill and Anthony Eden (though both spoke strongly in opposition of republicanism, Churchill’s attacks were blunted by his abrasive relationship to Edward and Eden was rather badly overshadowed by more famous politicians), but Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Basil Brooke. Unfortunately for the monarchists, Brooke’s abrasive nature made him an awkward figurehead, and his vocal anti-Catholicism did not go down as well with mainland Britons as it had with Ulster Protestants, who saw him as a bigot reminiscent of the Axis they had spent five and a half years fighting.

When the referendum was finally held, every nation comprising the United Kingdom voted in favour of republicanism except, as mentioned, Northern Ireland; Wales voted most strongly for it, with 58.3% of its voters and every county except Montgomeryshire supporting republicanism, whilst 54.7% of Scots and 52.2% of English voters also backed the republic option.

The result proved an upset, as by a majority of 53.2% to 46.8%, the UK voted to abolish its monarchy and become a republic. Some analysts have suggested the result was at least partly down to the ‘Edward factor’, as voters knew Edward would probably remain king for a long time to come should the Monarchy side win.

Edward abdicated on the 10th March and moved to France to retire, though much of the rest of the Windsor family remained in Britain and several of them, such as Edward’s brother Prince Albert and his daughters Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, were made peers of the House of Lords (one of the provisions the republican side had offered to compromise with advocates of the monarchy).

As a result of the referendum, the office of President of the United Kingdom was created, with the first election taking place in the summer of 1950. Given that the election held that February had been so hard-fought and close, it was not surprising that the presidential election would prove to be a clash between two major politicians from the two main parties…

View attachment 594016

(county results close-up)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Wikipedia Infoboxes VI (Do Not Post Current Politics or Political Figures Here)

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Liking it!View attachment 594014

The 1946 British institutional referendum was held on the 7th March 1946 to determine whether the United Kingdom would retain its monarchy or abolish the institution and become a republic. The referendum had been one of the policy planks of Clement Attlee’s Labour government, in response to the opposition of many of the party’s members to the behaviour of King Edward VIII since he ascended to the throne in 1936.

Republicanism had been growing in strength in Britain since the ascension of King Edward VIII to the throne in 1936, as he became the centre of controversy over his courtship of an American divorcee, Wallis Simpson. While he wished to marry Simpson, the opposition of the prime ministers of the UK and the Dominions (and the possibility of the British government resigning and a general election being forced) meant his aides cut communications between him and Simpson and forced him to remain King.

This ultimately proved extremely detrimental to both Edward (who was reportedly greatly depressed by these actions) and the British public, and Edward’s association with the ‘Cliveden set’, a group of upper-class socialites who favoured cooperation with Nazi Germany, made him and the monarchy deeply unpopular with Britons, particularly when World War II started in 1939.

Once Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940 and Britain cracked down on pro-Axis sentiment among the public, Edward became silent on the issue, but many people still believed him to be staying quiet out of fear of punishment by the government and not because he genuinely opposed Nazism. He also seemed to show little solidarity with the British public during the Blitz, and many were suspicious of the Nazis’ decision to bomb the House of Commons, but not Buckingham Palace.

The conditions of the referendum (such as the wording of the question- “Should the United Kingdom become a republic or remain a monarchy?”- and the date) were agreed during the early months of the Attlee government in mid-to-late 1945, and it was decided for the sake of civility that both Attlee and Edward would remain publicly neutral and would not partake in campaigning.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the referendum proved heavily partisan, as Labour voters overwhelmingly favoured the republic option and Conservatives and Unionists advocated for the monarchy; there were even reports of voter suppression in Northern Ireland, where over 81% of the vote went to the monarchy option and 96% of voters in County Down voted for the monarchy, more than any other county in the country.

Despite this, public sympathy for the royal family was extremely low, and leftist Labour politicians such as Nye Bevan and Stafford Cripps stressed that the tax breaks offered to the royals and the upkeep of their property could be put into policy programmes which would benefit the public.

By far the most vociferous opponent of the republican side was, surprisingly, not the major leaders of the Opposition Churchill and Anthony Eden (though both spoke strongly in opposition of republicanism, Churchill’s attacks were blunted by his abrasive relationship to Edward and Eden was rather badly overshadowed by more famous politicians), but Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Basil Brooke. Unfortunately for the monarchists, Brooke’s abrasive nature made him an awkward figurehead, and his vocal anti-Catholicism did not go down as well with mainland Britons as it had with Ulster Protestants, who saw him as a bigot reminiscent of the Axis they had spent five and a half years fighting.

When the referendum was finally held, every nation comprising the United Kingdom voted in favour of republicanism except, as mentioned, Northern Ireland; Wales voted most strongly for it, with 58.3% of its voters and every county except Montgomeryshire supporting republicanism, whilst 54.7% of Scots and 52.2% of English voters also backed the republic option.

The result proved an upset, as by a majority of 53.2% to 46.8%, the UK voted to abolish its monarchy and become a republic. Some analysts have suggested the result was at least partly down to the ‘Edward factor’, as voters knew Edward would probably remain king for a long time to come should the Monarchy side win.

Edward abdicated on the 10th March and moved to France to retire, though much of the rest of the Windsor family remained in Britain and several of them, such as Edward’s brother Prince Albert and his daughters Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, were made peers of the House of Lords (one of the provisions the republican side had offered to compromise with advocates of the monarchy).

As a result of the referendum, the office of President of the United Kingdom was created, with the first election taking place in the summer of 1950. Given that the election held that February had been so hard-fought and close, it was not surprising that the presidential election would prove to be a clash between two major politicians from the two main parties…

View attachment 594016

(county results close-up)

Edit: Addressed by user above, nevermind.

What was the fate of the Commonwealth realms and British colonies? Have they abolished the monarchy on their own accords, or do they continue to recognize Edward as King? If they have become republics, do they maintain close connections with the U.K.?View attachment 594014

The 1946 British institutional referendum was held on the 7th March 1946 to determine whether the United Kingdom would retain its monarchy or abolish the institution and become a republic. The referendum had been one of the policy planks of Clement Attlee’s Labour government, in response to the opposition of many of the party’s members to the behaviour of King Edward VIII since he ascended to the throne in 1936.

Republicanism had been growing in strength in Britain since the ascension of King Edward VIII to the throne in 1936, as he became the centre of controversy over his courtship of an American divorcee, Wallis Simpson. While he wished to marry Simpson, the opposition of the prime ministers of the UK and the Dominions (and the possibility of the British government resigning and a general election being forced) meant his aides cut communications between him and Simpson and forced him to remain King.

This ultimately proved extremely detrimental to both Edward (who was reportedly greatly depressed by these actions) and the British public, and Edward’s association with the ‘Cliveden set’, a group of upper-class socialites who favoured cooperation with Nazi Germany, made him and the monarchy deeply unpopular with Britons, particularly when World War II started in 1939.

Once Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940 and Britain cracked down on pro-Axis sentiment among the public, Edward became silent on the issue, but many people still believed him to be staying quiet out of fear of punishment by the government and not because he genuinely opposed Nazism. He also seemed to show little solidarity with the British public during the Blitz, and many were suspicious of the Nazis’ decision to bomb the House of Commons, but not Buckingham Palace.

The conditions of the referendum (such as the wording of the question- “Should the United Kingdom become a republic or remain a monarchy?”- and the date) were agreed during the early months of the Attlee government in mid-to-late 1945, and it was decided for the sake of civility that both Attlee and Edward would remain publicly neutral and would not partake in campaigning.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the referendum proved heavily partisan, as Labour voters overwhelmingly favoured the republic option and Conservatives and Unionists advocated for the monarchy; there were even reports of voter suppression in Northern Ireland, where over 81% of the vote went to the monarchy option and 96% of voters in County Down voted for the monarchy, more than any other county in the country.

Despite this, public sympathy for the royal family was extremely low, and leftist Labour politicians such as Nye Bevan and Stafford Cripps stressed that the tax breaks offered to the royals and the upkeep of their property could be put into policy programmes which would benefit the public.

By far the most vociferous opponent of the republican side was, surprisingly, not the major leaders of the Opposition Churchill and Anthony Eden (though both spoke strongly in opposition of republicanism, Churchill’s attacks were blunted by his abrasive relationship to Edward and Eden was rather badly overshadowed by more famous politicians), but Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Basil Brooke. Unfortunately for the monarchists, Brooke’s abrasive nature made him an awkward figurehead, and his vocal anti-Catholicism did not go down as well with mainland Britons as it had with Ulster Protestants, who saw him as a bigot reminiscent of the Axis they had spent five and a half years fighting.

When the referendum was finally held, every nation comprising the United Kingdom voted in favour of republicanism except, as mentioned, Northern Ireland; Wales voted most strongly for it, with 58.3% of its voters and every county except Montgomeryshire supporting republicanism, whilst 54.7% of Scots and 52.2% of English voters also backed the republic option.

The result proved an upset, as by a majority of 53.2% to 46.8%, the UK voted to abolish its monarchy and become a republic. Some analysts have suggested the result was at least partly down to the ‘Edward factor’, as voters knew Edward would probably remain king for a long time to come should the Monarchy side win.

Edward abdicated on the 10th March and moved to France to retire, though much of the rest of the Windsor family remained in Britain and several of them, such as Edward’s brother Prince Albert and his daughters Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, were made peers of the House of Lords (one of the provisions the republican side had offered to compromise with advocates of the monarchy).

As a result of the referendum, the office of President of the United Kingdom was created, with the first election taking place in the summer of 1950. Given that the election held that February had been so hard-fought and close, it was not surprising that the presidential election would prove to be a clash between two major politicians from the two main parties…

View attachment 594016

(county results close-up)

Also, why is the country still referred to as the United Kingdom if it's no longer a Kingdom?

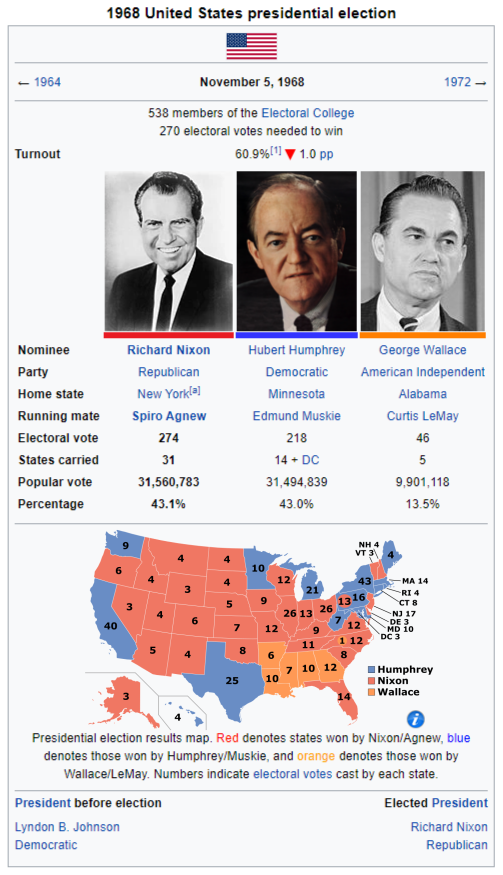

A wikibox I made for my TL, An Age of Science. The POD is in late 1965, and it centers around Richard Feynman running for and winning the California gubernatorial election in 1966 (over Ronald Reagan, mind you). So, while the butterflies aren't that big outside of California, they are about to become gigantic, since, although the election result hasn't changed, the way it was managed has changed greatly, and things are about to get heated up.

My original plan was just turn California blue to make it so Feynman's influence was felt, and I imagine it wouldn't cause so much chaos but, when I did the math and it did cause chaos, I just went with it and, through some research, arrived at this conclusion. After all, the plans for the faithless voters in Pennsylvania were being made, even before the election itself was through and Nixon won handily. So I don't see why they wouldn't go through with it. Although, if they did not, it'd be interesting to see how Congress would manage a contingent election. But I'm also glad with this road taken, since it allows for some drama over the Electoral College.

From the latest pseudo-update of Green Revolution on the Golden Gate. Writeup is here.

79th Academy Awards for film made in 2006

79th Academy Awards for film made in 2006

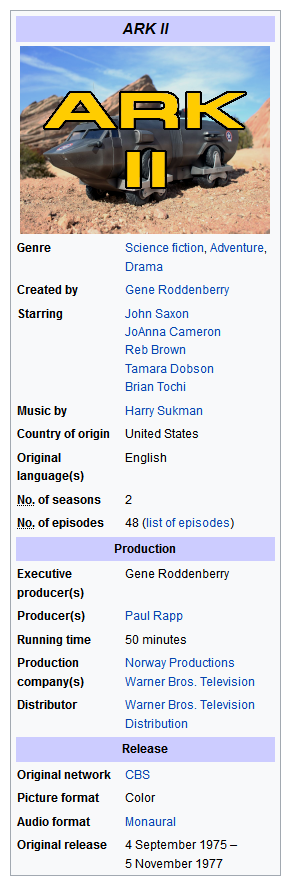

Is that the truck from Damnation Alley?Companion to this.

Instead of optioning Planet of the Apes, CBS goes with a post-apocalyptic "Wagon Train".

Yes. IMO, the only good thing in the movie.Is that the truck from Damnation Alley?

A Path Less Travelled: Part V

The Very Perfect, Gentle Giant of American Progressivism

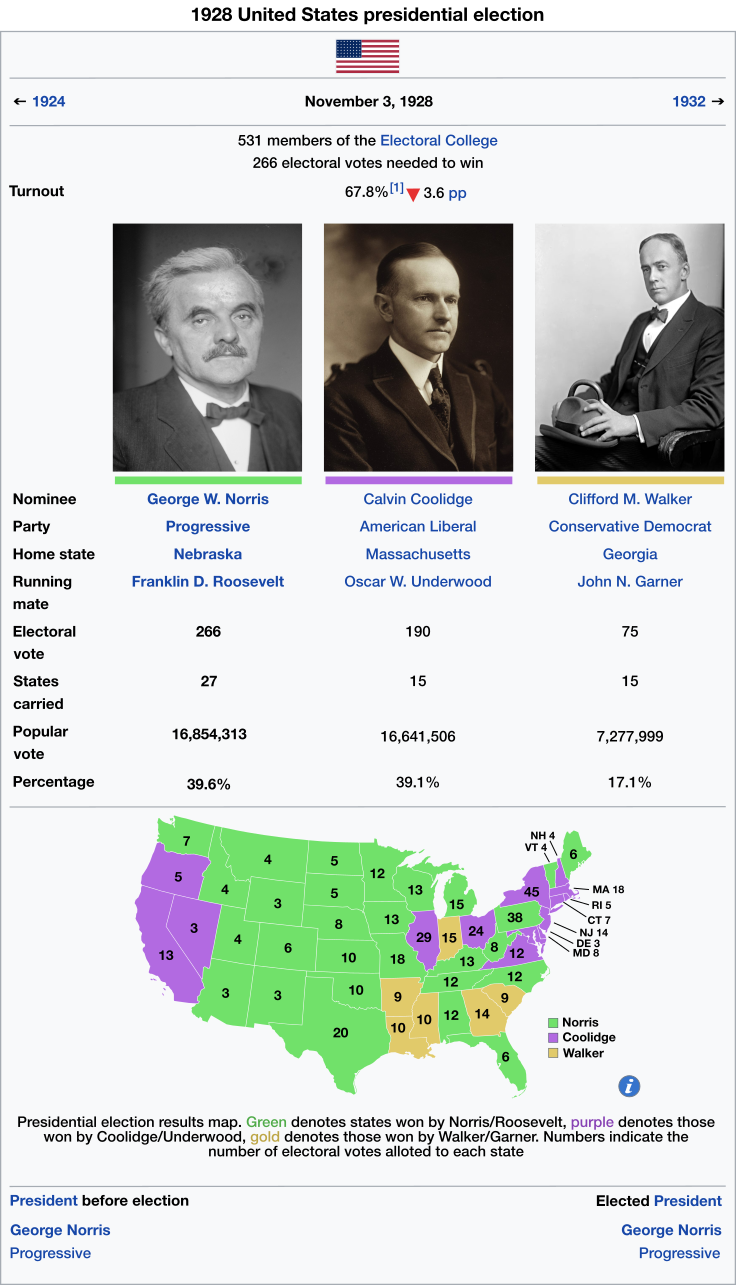

The 1928 United States presidential election was the 36th quadrennial presidential election, held on Saturday, November 3, 1928. Incumbent President George W. Norris defeated the American Liberal nominee, Senator Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts, and the Conservative Democratic nominee, Governor Clifford M. Walker of Georgia. Norris' election marked the fourth consecutive victory for the Progressive Party since Theodore Roosevelt won in 1916, and marked the first time since the party's founding that it did not improve its electoral result from the prior election.The Very Perfect, Gentle Giant of American Progressivism

After a decade and a half of growth and twelve years in power, the Progressive Party had begun to entrench itself as any party would. Their rise had dramatically changed the political landscape of the country, ushering in the Fifth Party System and causing the collapse of the both the Unionist-Republican Party⁽¹⁾ (also referred to as the GOP) and the Democratic Party. The effect this collapse had on American politics cannot be understated and though in many ways the American Liberals absorbed large parts of both the GOP and Democratic establishments, the Fifth Party System reshaped political allegiances across the country. Since its inception in 1912, the Progressive Party brought together other "progressive groups" around the nation that had otherwise struggled to influence the major parties; groups like the Georgists, democratic socialists, suffragists, prohibitionists, left and right wing populists, and agrarians. In addition, by the end of the 1910s, the vast majority of GOPers and Democrats in the West had joined the Party. These early defectors included both individuals who had been part of their respective party's progressive factions and others who hadn't, but openly became progressives⁽²⁾.

The result was a Progressive Party with varying factions, from moderate opportunistic members who joined the party to save their political careers, to radical reformers who wanted to continue making grand changes to American society. Presidents Roosevelt and Leonard Wood were unifying enough in that they didn't side too strongly with any faction. But it also meant they were not exactly representative of the party, and in some ways, such as both mens internationalism, they were far removed from the membership. Some hoped to renominate Wood to a third term so as to avoid confronting the issue of growing factionalism within the party in 1928, but the President's death in August 1927 pushed Vice-President Norris into power. Norris was far more inclined to enact change and far less nationalist than Wood. When President Norris announced he would seek a term in his own right, moderates and radicals alike felt they should challenge him in the 1928 Progressive Party primaries. But Norris' party opponents failed to unite around a candidate struck a chord, winning a majority of the primaries and receiving a large majority of the vote at the 1928 Progressive Party National Convention.

Norris was openly pushing for further progressive reforms, including the creation of public health insurance, unemployment insurance, and other social welfare and insurance programs. He also sought to start a number of federal projects to boost infrastructure, including expanding on the Muscle Shoals Bill and emulating its creation of regional planning agencies across the country. His opponents feared his continued presidency would lead to an economic catastrophe and the Liberals hoped that the slowing economic growth of the last year would help home in this point. As such, a number of prominent Liberals sought the American Liberal nomination, but eventually Calvin Coolidge was nominated at the 1928 American Liberal National Convention. At the convention, the Liberals selected recent convert Oscar Underwood of Alabama in an attempt to win voters in the South, where the collapse of the Fourth Party System had opened new opportunities. The Conservative Democrats also attacked Norris, but continued to push for their independence as a party as their base and ideology gravitated further around white supremacist conservatism. They nominated Clifford Walker at the 1928 Conservative Democratic National Convention in New Orleans, a favorite of the hardline wing of the party, against the wishes of minor, but growing numbers who wished for moderation. Walker's candidacy was largely influenced by his ties and connections to the Ku Klux Klan, which had reemerged in the 1920s across the South and other parts of the country.

The slowing economy ended up expanding the Liberals appeal considerably. Many parts of the country were considered to be at play in 1928, including the South, where the Progressives had made inroads throughout the decade and where the Liberals hoped to fight for with the collapse of the old Democrat order. The Conservative Democrats had managed to cement themselves across the Deep South, of course, by consisting of most of the individuals who controlled the region before the Democratic Party split earlier in the decade. But the collapse of the Democratic Party had weakened this stranglehold in certain states, allowing first the Progressives to gain ground and, with the nomination of Underwood, now the Liberals as well. Ultimately, however, the Liberals won only a single Southern state, Virginia, a result historians have attributed to Underwood's public and vocal disavowing of the Klan. The other major region contested was the Midwest and the Pacific Coast, which had gone largely Progressive in the past few elections, but which the Liberals felt they had a good chance of competing in. On the other hand, the Progressives hoped their nomination of Theodore Roosevelt's distant cousin, Franklin Roosevelt of New York, would help the party make inroads in the Northeast.

In the end, the election was an extremely close affair. The Liberals successfully campaigned on the slowing economy and Norris suffered as a result. At the same time, many of the changes that the Progressives had already enacted remained individually popular with the electorate, and the Progressives had cemented themselves in various parts of the country following the vacuum caused by the collapse of the GOP and the Democrats. The result was an extremely close popular vote, with Norris finishing half a percent ahead of Coolidge (39.6% to 39.1%, respectively). The electoral vote was not nearly as close, with Norris taking 76 electors over the Liberal nominee, but even that showed just how competitive the election truly was. Norris' 266 electoral votes were the exact number needed to win the election and weeks after the election fear mounted that a single faithless elector could throw the election to Congress. This ultimately did not come to pass, and Norris would be certified as the winner in the closest election since 1912. The Progressive inroads in the Upper South held, with Norris' involvement in the Muscle Shoals project shoring up his support in Kentucky, Tennessee and even North Carolina, and the ticket even managed surprise victories in Texas and Alabama, where the Liberals won enough votes to stop the Conservative Democrats from taking the state. The Liberals also showed that their appeal had grown - they won Ohio in the Midwest, Virginia in the South, and, most surprising of all, California, a state that had been considered a "home base" for the Progressives. The contested nature of the election also produced a surprising Conservative Democratic victory in Indiana, which has since been credited to that state's large Klan influence at the time. Many states were decided by extremely small margins and ten states⁽³⁾ were won by less than a percentage point.

⁽¹⁾ Throughout In the 19th Century, there were two influential political parties that were known as the Republican Party, though they operated in different eras. In the 20th century, political scientists popularized the terms Democratic-Republican Party and Unionist-Republican Party as a means of differentiating the two distinct, but very influential groups. Though other names have been used to describe the two groups, these have become the most widely accepted in the modern era and have been incorporated into the American lexicon. The Democratic-Republican Party was one of the foundational political parties of the United States, having been founded in 1792 and dominating American government to such a degree that the nation became a one-party state in all but name at its height (See Era of Good Feelings, 1816-1824). Its modern name draws from its commitment to Jeffersonian Democracy. The dominance of the party ultimately led to its demise as factions began deviating in opinion and then hardened into definite sides following the 1824 U.S. presidential election. The Union-Republican Party was founded in 1854 following the merger of abolitionists, ex-Whigs (the major opposition to the Democrats in the Second Party System) and ex-Free Soilers (a minor, third party of the Second Party System). It's name was, in fact, an homage to the original Republican Party, though it didn't really follow the Jeffersonian ideals of its namesake. It dominated the Third & Fourth Party Systems (1856-1892; 1896-1920) opposite the Democratic Party (itself founded in 1828 as the heirs of the original republicans). The modern name derives from the latter Republicans having led the Union to victory during the American Civil War, under the leadership of President Abraham Lincoln. Unionist-Republicans won twelve of the seventeen presidential elections that occurred between 1856 and 1920, before suffering severe defections during the Progressive Re-Alignment and eventually merging with the urban and classical liberal factions of the collapsing Democratic Party to form the modern American Liberal Party. During its heyday, the Unionist-Republicans came to adopt the nickname of the Grand Old Party, and the initials of this nickname, GOP, has persisted in the modern day as an interchangeable name for the party.

⁽²⁾ Following Theodore Roosevelt's plurality finish in 1912, his vocal opposition to Republican President Nicholas Murray Butler and the Progressive Party's successes and subsequent victory in 1916, progressives and populist members of most the Unionist-Republicans large number of Unionist-Republicans in the West who had formally professed moderate or even conservative beliefs, converted and professed their acceptance and support for Roosevelt and progressivism. These individuals should not be confused with other defectors who already identified with the progressive factions of either the GOP or the Democrats.

⁽³⁾ The states of Alabama, California, Florida, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, Vermont and Washington were each won by less than a percentage point. Eight were won by Norris. Had he lost even one of these states, it would have cost him the election.

⁽²⁾ Following Theodore Roosevelt's plurality finish in 1912, his vocal opposition to Republican President Nicholas Murray Butler and the Progressive Party's successes and subsequent victory in 1916, progressives and populist members of most the Unionist-Republicans large number of Unionist-Republicans in the West who had formally professed moderate or even conservative beliefs, converted and professed their acceptance and support for Roosevelt and progressivism. These individuals should not be confused with other defectors who already identified with the progressive factions of either the GOP or the Democrats.

⁽³⁾ The states of Alabama, California, Florida, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, Vermont and Washington were each won by less than a percentage point. Eight were won by Norris. Had he lost even one of these states, it would have cost him the election.

–•–

APLT - Index

Part I. 1912 U.S. presidential election

Part II. 1916 U.S. presidential election

Part III. 1920 U.S. presidential election

Part IV. 1924 U.S. presidential election

This is really cool!A Path Less Travelled: Part VThe 1928 United States presidential election was the 36th quadrennial presidential election, held on Saturday, November 3, 1928. Incumbent President George W. Norris defeated the American Liberal nominee, Senator Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts, and the Conservative Democratic nominee, Governor Clifford M. Walker of Georgia. Norris' election marked the fourth consecutive victory for the Progressive Party since Theodore Roosevelt won in 1916, and marked the first time since the party's founding that it did not improve its electoral result from the prior election.

The Very Perfect, Gentle Giant of American Progressivism

View attachment 594111

After a decade and a half of growth and twelve years in power, the Progressive Party had begun to entrench itself as any party would. Their rise had dramatically changed the political landscape of the country, ushering in the Fifth Party System and causing the collapse of the both the Unionist-Republican Party⁽¹⁾ (also referred to as the GOP) and the Democratic Party. The effect this collapse had on American politics cannot be understated and though in many ways the American Liberals absorbed large parts of both the GOP and Democratic establishments, the Fifth Party System reshaped political allegiances across the country. Since its inception in 1912, the Progressive Party brought together other "progressive groups" around the nation that had otherwise struggled to influence the major parties; groups like the Georgists, democratic socialists, suffragists, prohibitionists, left and right wing populists, and agrarians. In addition, by the end of the 1910s, the vast majority of GOPers and Democrats in the West had joined the Party. These early defectors included both individuals who had been part of their respective party's progressive factions and others who hadn't, but openly became progressives⁽²⁾.

The result was a Progressive Party with varying factions, from moderate opportunistic members who joined the party to save their political careers, to radical reformers who wanted to continue making grand changes to American society. Presidents Roosevelt and Leonard Wood were unifying enough in that they didn't side too strongly with any faction. But it also meant they were not exactly representative of the party, and in some ways, such as both mens internationalism, they were far removed from the membership. Some hoped to renominate Wood to a third term so as to avoid confronting the issue of growing factionalism within the party in 1928, but the President's death in August 1927 pushed Vice-President Norris into power. Norris was far more inclined to enact change and far less nationalist than Wood. When President Norris announced he would seek a term in his own right, moderates and radicals alike felt they should challenge him in the 1928 Progressive Party primaries. But Norris' party opponents failed to unite around a candidate struck a chord, winning a majority of the primaries and receiving a large majority of the vote at the 1928 Progressive Party National Convention.

Norris was openly pushing for further progressive reforms, including the creation of public health insurance, unemployment insurance, and other social welfare and insurance programs. He also sought to start a number of federal projects to boost infrastructure, including expanding on the Muscle Shoals Bill and emulating its creation of regional planning agencies across the country. His opponents feared his continued presidency would lead to an economic catastrophe and the Liberals hoped that the slowing economic growth of the last year would help home in this point. As such, a number of prominent Liberals sought the American Liberal nomination, but eventually Calvin Coolidge was nominated at the 1928 American Liberal National Convention. At the convention, the Liberals selected recent convert Oscar Underwood of Alabama in an attempt to win voters in the South, where the collapse of the Fourth Party System had opened new opportunities. The Conservative Democrats also attacked Norris, but continued to push for their independence as a party as their base and ideology gravitated further around white supremacist conservatism. They nominated Clifford Walker at the 1928 Conservative Democratic National Convention in New Orleans, a favorite of the hardline wing of the party, against the wishes of minor, but growing numbers who wished for moderation. Walker's candidacy was largely influenced by his ties and connections to the Ku Klux Klan, which had reemerged in the 1920s across the South and other parts of the country.

The slowing economy ended up expanding the Liberals appeal considerably. Many parts of the country were considered to be at play in 1928, including the South, where the Progressives had made inroads throughout the decade and where the Liberals hoped to fight for with the collapse of the old Democrat order. The Conservative Democrats had managed to cement themselves across the Deep South, of course, by consisting of most of the individuals who controlled the region before the Democratic Party split earlier in the decade. But the collapse of the Democratic Party had weakened this stranglehold in certain states, allowing first the Progressives to gain ground and, with the nomination of Underwood, now the Liberals as well. Ultimately, however, the Liberals won only a single Southern state, Virginia, a result historians have attributed to Underwood's public and vocal disavowing of the Klan. The other major region contested was the Midwest and the Pacific Coast, which had gone largely Progressive in the past few elections, but which the Liberals felt they had a good chance of competing in. On the other hand, the Progressives hoped their nomination of Theodore Roosevelt's distant cousin, Franklin Roosevelt of New York, would help the party make inroads in the Northeast.

In the end, the election was an extremely close affair. The Liberals successfully campaigned on the slowing economy and Norris suffered as a result. At the same time, many of the changes that the Progressives had already enacted remained individually popular with the electorate, and the Progressives had cemented themselves in various parts of the country following the vacuum caused by the collapse of the GOP and the Democrats. The result was an extremely close popular vote, with Norris finishing half a percent ahead of Coolidge (39.6% to 39.1%, respectively). The electoral vote was not nearly as close, with Norris taking 76 electors over the Liberal nominee, but even that showed just how competitive the election truly was. Norris' 266 electoral votes were the exact number needed to win the election and weeks after the election fear mounted that a single faithless elector could throw the election to Congress. This ultimately did not come to pass, and Norris would be certified as the winner in the closest election since 1912. The Progressive inroads in the Upper South held, with Norris' involvement in the Muscle Shoals project shoring up his support in Kentucky, Tennessee and even North Carolina, and the ticket even managed surprise victories in Texas and Alabama, where the Liberals won enough votes to stop the Conservative Democrats from taking the state. The Liberals also showed that their appeal had grown - they won Ohio in the Midwest, Virginia in the South, and, most surprising of all, California, a state that had been considered a "home base" for the Progressives. The contested nature of the election also produced a surprising Conservative Democratic victory in Indiana, which has since been credited to that state's large Klan influence at the time. Many states were decided by extremely small margins and ten states⁽³⁾ were won by less than a percentage point.

⁽¹⁾ Throughout In the 19th Century, there were two influential political parties that were known as the Republican Party, though they operated in different eras. In the 20th century, political scientists popularized the terms Democratic-Republican Party and Unionist-Republican Party as a means of differentiating the two distinct, but very influential groups. Though other names have been used to describe the two groups, these have become the most widely accepted in the modern era and have been incorporated into the American lexicon. The Democratic-Republican Party was one of the foundational political parties of the United States, having been founded in 1792 and dominating American government to such a degree that the nation became a one-party state in all but name at its height (See Era of Good Feelings, 1816-1824). Its modern name draws from its commitment to Jeffersonian Democracy. The dominance of the party ultimately led to its demise as factions began deviating in opinion and then hardened into definite sides following the 1824 U.S. presidential election. The Union-Republican Party was founded in 1854 following the merger of abolitionists, ex-Whigs (the major opposition to the Democrats in the Second Party System) and ex-Free Soilers (a minor, third party of the Second Party System). It's name was, in fact, an homage to the original Republican Party, though it didn't really follow the Jeffersonian ideals of its namesake. It dominated the Third & Fourth Party Systems (1856-1892; 1896-1920) opposite the Democratic Party (itself founded in 1828 as the heirs of the original republicans). The modern name derives from the latter Republicans having led the Union to victory during the American Civil War, under the leadership of President Abraham Lincoln. Unionist-Republicans won twelve of the seventeen presidential elections that occurred between 1856 and 1920, before suffering severe defections during the Progressive Re-Alignment and eventually merging with the urban and classical liberal factions of the collapsing Democratic Party to form the modern American Liberal Party. During its heyday, the Unionist-Republicans came to adopt the nickname of the Grand Old Party, and the initials of this nickname, GOP, has persisted in the modern day as an interchangeable name for the party.

⁽²⁾ Following Theodore Roosevelt's plurality finish in 1912, his vocal opposition to Republican President Nicholas Murray Butler and the Progressive Party's successes and subsequent victory in 1916, progressives and populist members of most the Unionist-Republicans large number of Unionist-Republicans in the West who had formally professed moderate or even conservative beliefs, converted and professed their acceptance and support for Roosevelt and progressivism. These individuals should not be confused with other defectors who already identified with the progressive factions of either the GOP or the Democrats.

⁽³⁾ The states of Alabama, California, Florida, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, Vermont and Washington were each won by less than a percentage point. Eight were won by Norris. Had he lost even one of these states, it would have cost him the election.–•–

APLT - Index

Part I. 1912 U.S. presidential election

Part II. 1916 U.S. presidential election

Part III. 1920 U.S. presidential election

Part IV. 1924 U.S. presidential election

"There Ain't No Such Thing as a Free Computer"

The Technologist Party was founded in the early years of the Digital Revolution in California. It was not a very successful party when first founded. It gained success as some more charismatic leaders started to win small local victories in places like California, Seattle, and New Mexico. It gained more steam when the party merged with the Libertarian Party in 1975, which had been loosing steam itself due to infighting. This injected the party with a new energy. The Technologists weren't breaking any records, but they still were an increasing number of votes gaining votes. Their first real victory came in 1978 with the election of Robert A. Heinlein to the House of Representatives. Heinlein was one of the loudest proponents of increasing militarization of America, increased funding for NASA, and allowing more rights for the average citizen. Though he also also was a proponent of Social Credit, though in small amounts. His unique view would develop into an ideology itself and become a core faction of the Technologist Party. This was not the only faction. The other major factions included the Libertarians, the Environmentalists, the "Astroboys", and the Transhumanists. The Libertarians were mostly based in the South with small holdouts in places like Colorado and Idaho. Their ideology is based around the former Libertarian Party. The Environmentalists are proponents of using technology to improve the state of the world. This is most popular in the northern parts of Washington State, Southern California, and New England. The "Astroboys" is a faction dominated by those who want space travel and colonization to be a more major focus of the party. Popular wherever a NASA site is located. The Transhumanists believe that the only way for society to move forward is to augment humanity to reach its full potential. They also include the internal factions of techno-progressivism, anarcho-transhumanism, democratic transhumanism, and libertarian transhumanism. These factions sometimes overlap.

Despite factionalization, there are a few things that are generally agreed upon. Digital rights, techno-libertarianism, the belief that all things should be in some form of public domain as well as the openness of technology, and democratic technocracy, a democracy that is based on the experts being elected to hold positions in office. The later is mostly held by the Environmental, "Astroboy", and Transhumanist factions. The Heinleinian and Libertarian factions tend to disagree with this sentiment a little more.

The party found new life after 9/11 and the increasing of surveillance of American citizens. Party members became more vocal about ending it. It also helped that the party started getting bankrolled by various tech companies across the entire United States like Mircosoft, Apple, IBM, and Google. By 2020, the Technologist Party had cemented itself as America's largest third party. It holds seats in California, Washington, Nevada, Massachusetts, Texas, and Oregon. It holds two governorships through Microsoft founder Bill Gates (T-WA) and Dell founder Michael Dell (T-TX). Its single senate seat is held by Elliot Zuckerberg (T-CA). Its current Presidential Ticket for the 2020 Presidential Cycle is Rep. Stephen Gary Wozniak (T-CA) and State Sen. Gabe Newell (T-WA) who won the ticket after a competitive primary that included Rep. Wozniak, Fmr. Rep. Tim Schafer (T-CA), State Senator Edward J. Boon (T-IL), State Representative Todd Howard (T-PA), State Sen. and Former Astronaut Christopher J. Ferguson (T-PA), and Gabriel Rothblatt (T-FL).

I hope there's not also a Pirate Party or else that'd be two based options"There Ain't No Such Thing as a Free Computer"The Technologist Party was founded in the early years of the Digital Revolution in California. It was not a very successful party when first founded. It gained success as some more charismatic leaders started to win small local victories in places like California, Seattle, and New Mexico. It gained more steam when the party merged with the Libertarian Party in 1975, which had been loosing steam itself due to infighting. This injected the party with a new energy. The Technologists weren't breaking any records, but they still were an increasing number of votes gaining votes. Their first real victory came in 1978 with the election of Robert A. Heinlein to the House of Representatives. Heinlein was one of the loudest proponents of increasing militarization of America, increased funding for NASA, and allowing more rights for the average citizen. Though he also also was a proponent of Social Credit, though in small amounts. His unique view would develop into an ideology itself and become a core faction of the Technologist Party. This was not the only faction. The other major factions included the Libertarians, the Environmentalists, the "Astroboys", and the Transhumanists. The Libertarians were mostly based in the South with small holdouts in places like Colorado and Idaho. Their ideology is based around the former Libertarian Party. The Environmentalists are proponents of using technology to improve the state of the world. This is most popular in the northern parts of Washington State, Southern California, and New England. The "Astroboys" is a faction dominated by those who want space travel and colonization to be a more major focus of the party. Popular wherever a NASA site is located. The Transhumanists believe that the only way for society to move forward is to augment humanity to reach its full potential. They also include the internal factions of techno-progressivism, anarcho-transhumanism, democratic transhumanism, and libertarian transhumanism. These factions sometimes overlap.

Despite factionalization, there are a few things that are generally agreed upon. Digital rights, techno-libertarianism, the belief that all things should be in some form of public domain as well as the openness of technology, and democratic technocracy, a democracy that is based on the experts being elected to hold positions in office. The later is mostly held by the Environmental, "Astroboy", and Transhumanist factions. The Heinleinian and Libertarian factions tend to disagree with this sentiment a little more.

The party found new life after 9/11 and the increasing of surveillance of American citizens. Party members became more vocal about ending it. It also helped that the party started getting bankrolled by various tech companies across the entire United States like Mircosoft, Apple, IBM, and Google. By 2020, the Technologist Party had cemented itself as America's largest third party. It holds seats in California, Washington, Nevada, Massachusetts, Texas, and Oregon. It holds two governorships through Microsoft founder Bill Gates (T-WA) and Dell founder Michael Dell (T-TX). Its single senate seat is held by Elliot Zuckerberg (T-CA). Its current Presidential Ticket for the 2020 Presidential Cycle is Rep. Stephen Gary Wozniak (T-CA) and State Sen. Gabe Newell (T-WA) who won the ticket after a competitive primary that included Rep. Wozniak, Fmr. Rep. Tim Schafer (T-CA), State Senator Edward J. Boon (T-IL), State Representative Todd Howard (T-PA), State Sen. and Former Astronaut Christopher J. Ferguson (T-PA), and Gabriel Rothblatt (T-FL).

Are the colors reversed on the map? The way it currently looks appears to have Northern Ireland voting heavily republican and much of Wales voting for the monarchy, which is the opposite of what was described.

Yeah, they are. I think I assumed blue was monarchy and red was republic because the Tories supported the former and Labour the latter or something, I'll correct it in a minute.

What was the fate of the Commonwealth realms and British colonies? Have they abolished the monarchy on their own accords, or do they continue to recognize Edward as King? If they have become republics, do they maintain close connections with the U.K.?

Also, why is the country still referred to as the United Kingdom if it's no longer a Kingdom?

The Commonwealth countries and colonies became republics, but are still part of the Commonwealth without being ruled by a monarch in the same sort of way India is in OTL, for example. For the most part, the Commonwealth remains about as closely connected as in OTL, and things like the British Parliament technically retaining the right to amend Canada's laws until the Constitution Act 1982 don't change. The repealing of the British Crown also leads the term 'crown colony' to be replaced with 'Commonwealth colony', and most of the larger Commonwealth countries like Australia, Canada and (as in OTL) India introduce a President, though they are generally given limited powers (and in Canada the candidates are required to be non-partisan, though they usually come from the major parties who just resign from said parties to get nominated).

As for the country being called the United Kingdom, that changes after the referendum- the official name for the country becomes the United Republic of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, but colloquially it is almost always referred to as 'Britain' rather than 'the UR' since the former term has a longer history (and is less offensive to the pro-monarchy side that lost the referendum). That'll be reflected in future wikiboxes with them calling it the 'British presidential election'.

Liking it!

Thank you! I'm gonna start work on the 1950 election shortly.

The 1950 British presidential election was held on the 6th July, 1950, to elect the first President of the United Republic of Great Britain and Ireland (colloquially known as the President of Britain). While the office had de jure existed since after the constitutional referendum of 1946, it had been vacant until this point due to disagreements over how it should be set up.

In the intervening 4 years, the election system for the office had been organized; like the US presidential system, it was to be elected by voters nationwide in a single-round election instead of by the legislature like in France or West Germany, but unlike the US, the result would be based solely on the popular vote rather than any sort of electoral college system. The President would be elected to a five-year term, with the first term commencing on the 7th July 1950 and ending on the 8th July 1955 (the day after the 1950 and 1955 presidential elections respectively), and Buckingham Palace was made the President’s home as the Windsor family moved to Windsor Castle after the abolition of the monarchy.

Nominations for each major party were decided by the executives of each party, with both Labour and the Conservatives deciding for the first election to choose their nominee based on a vote by members of their parliamentary parties. Due to their low funds and high debt after their poor performance in the general election held earlier that year, Clem Davies’ Liberal Party chose not to put forward a candidate for President.

The figures put forward by Labour and the Tories were both extremely well-known and well-regarded- Aneurin Bevan for Labour, and Winston Churchill for the Tories. Both of them are believed to have been put forward and ultimately won nomination because of internal conflicts within their parties, as the Attlee cabinet had grown to distrust Bevan as one of the most adamant leftist figures in the party and someone prone to making contentious comments about those he opposed (most famously his declaration of Tories to be ‘lower than vermin’, which some in Attlee’s government considered to have been a key factor in Labour’s dramatically reduced majority in the February general election, where it fell from a 146-seat majority to a 5-seat one), and many Tories were concerned Churchill was not an effective parliamentary leader, with Anthony Eden being believed to do most of the work for the party in opposition while Churchill had made very loud condemnations of Labour’s popular social reforms (the ‘some sort of Gestapo’ remark and his comparisons of the NHS to communism, for instance).

Despite this distrust, significant sections of the British public, or at least the two main parties’ rank and file, were enamoured with one or the other- Churchill was upheld as the man who saved Britain from the Nazis, and Bevan as the father of the NHS and an adamant supporter of the welfare state. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the popularity of both men and their stark ideological differences, the campaign proved very contentious, with Bevan supporters citing Churchill’s aggressive attacks on the welfare state and suggesting he would seek to destroy it, while Churchill supporters argued Bevan would ‘rubber stamp’ any policy Attlee put through and block a future Tory government’s policies if they won a subsequent general election in the intervening 5 years (which was seen as probable given Attlee’s government was hanging on by a thread).

Experts correctly guessed the race would be extremely close, but it was unclear from the opinion polls who had the edge; something often cited as ultimately tipping the balance in Churchill’s favour was the endorsement of his candidacy by the majority of the Liberals, including Clem Davies, while only Megan Lloyd George and Edgar Granville (who would ultimately join Labour) gave their support to Bevan. In any case, the election ultimately went to Churchill, who took 51.2% of the vote to 48.1% for Bevan. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bevan won a resounding majority of the vote in his native Wales and a smaller majority in Scotland, while Churchill beat him in England and would have swept Northern Ireland if not for Nationalists enough backing Bevan in Catholic-majority County Fermanagh to give him a small 50-47 plurality. This would be the closest British presidential election until 1970.

Once Churchill ascended to the Presidency, Eden became the new Leader of the Opposition and Bevan made a disgruntled return to Attlee’s cabinet, though he would keep a much lower profile in public life until his death in 1960. Ironically, despite the worst fears expressed in the campaign the ‘cohabitation’ with Churchill in Buckingham Palace and Attlee in 10 Downing Street, which lasted until Attlee lost a motion of no confidence and snap general election in 1953, was fairly civil, as Churchill mostly served to water down Labour policy programmes such as the nationalization programmes and reduce the funding for them rather than veto them altogether.

Once Eden came to power after the 1953 election with a majority of 40, Churchill did fairly little proactively, mostly giving assent to policies the Eden government proposed. For the 1955 election, it was fairly clear Churchill was not interested in seeking a second term, especially since he was entering his 80s, and neither were the Tories.

The common story about the 1955 Tory nomination process, though perhaps one exaggerated in its dramatics by history, is that once it became clear Churchill would be retiring that July, one of the party’s main grandees, Lord Salisbury, convened the Cabinet and asked of them, fighting his inability to pronounce the letter R, “Is it to be Wab or Hawold?”

The answer they came to would ultimately determine the man who, while not the longest-serving President of Britain, would define role of the British presidency (or ‘wole of the Bwitish pwesidency’, as Salisbury might have put it) for decades to come.

(results by county close-up)

Last edited:

View attachment 594297

The 1950 British presidential election was held on the 6th July, 1950, to elect the first President of the United Republic of Great Britain and Ireland (colloquially known as the President of Britain). While the office had de jure existed since after the constitutional referendum of 1946, it had been vacant until this point due to disagreements over how it should be set up.

In the intervening 4 years, the election system for the office had been organized; like the US presidential system, it was to be elected by voters nationwide in a single-round election instead of by the legislature like in France or West Germany, but unlike the US, the result would be based solely on the popular vote rather than any sort of electoral college system. The President would be elected to a five-year term, with the first term commencing on the 7th July 1950 and ending on the 8th July 1955 (the day after the 1950 and 1955 presidential elections respectively), and Buckingham Palace was made the President’s home as the Windsor family moved to Windsor Castle after the abolition of the monarchy.

Nominations for each major party were decided by the executives of each party, with both Labour and the Conservatives deciding for the first election to choose their nominee based on a vote by members of their parliamentary parties. Due to their low funds and high debt after their poor performance in the general election held earlier that year, Clem Davies’ Liberal Party chose not to put forward a candidate for President.

The figures put forward by Labour and the Tories were both extremely well-known and well-regarded- Aneurin Bevan for Labour, and Winston Churchill for the Tories. Both of them are believed to have been put forward and ultimately won nomination because of internal conflicts within their parties, as the Attlee cabinet had grown to distrust Bevan as one of the most adamant leftist figures in the party and someone prone to making contentious comments about those he opposed (most famously his declaration of Tories to be ‘lower than vermin’, which some in Attlee’s government considered to have been a key factor in Labour’s dramatically reduced majority in the February general election, where it fell from a 146-seat majority to a 5-seat one), and many Tories were concerned Churchill was not an effective parliamentary leader, with Anthony Eden being believed to do most of the work for the party in opposition while Churchill had made very loud condemnations of Labour’s popular social reforms (the ‘some sort of Gestapo’ remark and his comparisons of the NHS to communism, for instance).

Despite this distrust, significant sections of the British public, or at least the two main parties’ rank and file, were enamoured with one or the other- Churchill was upheld as the man who saved Britain from the Nazis, and Bevan as the father of the NHS and an adamant supporter of the welfare state. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the popularity of both men and their stark ideological differences, the campaign proved very contentious, with Bevan supporters citing Churchill’s aggressive attacks on the welfare state and suggesting he would seek to destroy it, while Churchill supporters argued Bevan would ‘rubber stamp’ any policy Attlee put through and block a future Tory government’s policies if they won a subsequent general election in the intervening 5 years (which was seen as probable given Attlee’s government was hanging on by a thread).

Experts correctly guessed the race would be extremely close, but it was unclear from the opinion polls who had the edge; something often cited as ultimately tipping the balance in Churchill’s favour was the endorsement of his candidacy by the majority of the Liberals, including Clem Davies, while only Megan Lloyd George and Edgar Granville (who would ultimately join Labour) gave their support to Bevan. In any case, the election ultimately went to Churchill, who took 51.2% of the vote to 48.1% for Bevan. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bevan won a resounding majority of the vote in his native Wales and a smaller majority in Scotland, while Churchill beat him in England and would have swept Northern Ireland if not for Nationalists enough backing Bevan in Catholic-majority County Fermanagh to give him a small 50-47 plurality. This would be the closest British presidential election until 2015.

Once Churchill ascended to the Presidency, Eden became the new Leader of the Opposition and Bevan made a disgruntled return to Attlee’s cabinet, though he would keep a much lower profile in public life until his death in 1960. Ironically, despite the worst fears expressed in the campaign the ‘cohabitation’ with Churchill in Buckingham Palace and Attlee in 10 Downing Street, which lasted until Attlee lost a motion of no confidence and snap general election in 1953, was fairly civil, as Churchill mostly served to water down Labour policy programmes such as the nationalization programmes and reduce the funding for them rather than veto them altogether.

Once Eden came to power after the 1953 election with a majority of 40, Churchill did fairly little proactively, mostly giving assent to policies the Eden government proposed. For the 1955 election, it was fairly clear Churchill was not interested in seeking a second term, especially since he was entering his 80s, and neither were the Tories.

The common story about the 1955 Tory nomination process, though perhaps one exaggerated in its dramatics by history, is that once it became clear Churchill would be retiring that July, one of the party’s main grandees, Lord Hailsham, convened the Cabinet and asked of them, fighting his inability to pronounce the letter R, “Is it to be Wab or Hawold?”

The answer they came to would ultimately determine the man who, while not the longest-serving President of Britain, would define role of the British presidency (or ‘wole of the Bwitish pwesidency’, as Hailsham might have put it) for decades to come.

View attachment 594298

(results by county close-up)

Britain is a semi-presidential republic after having been the defining parliamentary system in the world? Interesting.

Which is pretty much what France became in OTL after the collapse of its monarchy.Britain is a semi-presidential republic after having been the defining parliamentary system in the world? Interesting.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: