You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Wikipedia Infoboxes VI (Do Not Post Current Politics or Political Figures Here)

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Hughes won in the states of Iowa, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Vermont.

Thanks James Gordon Brown. I guess Hughes wasn't that great of a president in that timeline, was he? At least he's probably a bit better than Wilson, though.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Well, while I'm here, might as well add this infobox and writeup.

Remember Me: A Coco infobox series

Ernesto de la Cruz

Héctor Rivera

Remember Me (song) (you are here)

Remember Me is a Mexican pop song sung by Ernesto de la Cruz and was written by his touring partner and childhood best friend Héctor Rivera. It is often noted as being de la Cruz's signature song.

The song debuted in 1932 as a ranchero-style Mexican pop song and would soon become de la Cruz's most popular song. The song was sung as s a plea from Ernesto to his fans to keep him in their minds even as he tours in other places. On 2 November 1942, it would also ironically be de la Cruz's final performance. While performing in Mexico City on stage finishing a performance of the song, a backstage hand got distracted and accidently pulled the lever for the stage's giant church bell; Ernesto, being right under the bell at the moment, was crushed by it and killed instantly.

While Ernesto de la Cruz mentioned he wrote the song, it would later be revealed in late 2017 that Remember Me (and nearly all of the other songs that were sung by him) was actually written by Héctor Rivera, his 1921 touring partner and childhood best friend. According to Rivera's daughter Socorro "Coco" shortly before her death, he had wrote the song in 1921 when she was only three years old as a lullaby when he has to travel far as a traveling artist. Her great-grandson Miguel had also sung the song to her to restore the memory of her long lost father. Coco also revealed that she kept all her father's letters he wrote to her on the road. Those letters featuring the lyrics for the song and all the other songs Rivera wrote to Coco and her mother (as well as his famous skull guitar) are now on display at the Rivera Family Shoe Makers in Santa Cecilia.

A record of the song sung by Ernesto de la Cruz.

Ernesto de la Cruz's final performance (1942) (audio only)

Last edited:

I played President Elect and let the computer do everything. I changed some settings for the 80 election.

Edit: I fixed H.W.'s home state

Last edited:

American India?I was bored so I decided to make an American Prime Minister list that has Joseph Smith, Huey Long and George Custer as politicians.

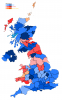

The 1960 British presidential election was the third election for the President of Britain, held on the 7th July 1960. Incumbent President Rab Butler, a Conservative, was running for re-election to a second term.

From the beginning, Butler was strongly favoured to win re-election, but despite this the Labour Party were eager to try and defeat him, not least because of rumours that if Butler were to win convincingly enough, Macmillan would take it as a sign to call a general election to try and bolster his small parliamentary majority.

It was also seen by Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell as an important opportunity to enact his authority by funding and endorsing the campaign of his favoured candidate, Anthony Crosland. Since the main opponent to Crosland from the left was Richard Crossman, the right-wing papers predictably joked that Labour’s parliamentary party was ‘cross-eyed’.

Overcoming the Bevanites was to prove surprisingly easy for Gaitskell on this occasion, though, given that Bevan himself was seriously ill (he would ultimately die the day before the election, which led to campaigning being ceased prematurely) and since he had split his supporters by advocating against unilateral nuclear disarmament. Consequently, Crosland won the nomination and proved surprisingly adept at unifying the party against Butler, though this only really managed to narrow his deficit in the polls rather than get him to the point of having a chance to beat Butler.

The big surprise of the 1960 election came from neither of the major parties, but from the Liberals, fighting their first ever presidential election campaign. From their small 6-seat grouping in the Commons, only one was convinced to run a presidential campaign: Mark Bonham Carter, MP for Torrington elected in a shock victory over the Tories in a 1958 by-election who held his seat narrowly at the general election held 4 months later. Bonham-Carter’s family were strongly involved with Liberal politics and he was himself a close friend of then-leader Jo Grimond, plus at 38 he was younger and more telegenic than Butler or Crosland. Thanks to all this, for the first time the Liberals felt able to mount a proper campaign. It certainly helped that they could accumulate many protest votes, and they benefitted far more from the view of the election as a foregone conclusion than Labour did.

Once the votes were counted, it was clearly a second blowout for Butler, who took 53.4% of the vote to 36.3% for Crosland (the poorest share for Labour in a national election since 1935), but Bonham Carter achieved a staggering 10% of the vote, the highest for the Liberals in any election since 1929. Even if it didn’t amount to any electoral gain, it was a huge morale boost for the Liberals.

The one silver lining for Labour, so it seemed, was that perhaps at least Bonham Carter had taken so much wind out of the Tories’ sails that Macmillan wouldn’t want to risk an election. This proved not to be the case- Macmillan did indeed call an election for the 8th September, impressing voters by his unflappable response to the Liberal surge. While the Liberals held their six seats and gained a seventh as Jeremy Thorpe took North Devon for the first time, the big news of the election was the Tories bolstering their majority from 24 to 106.

Almost immediately after these two major electoral victories, though, things started to go horribly wrong for the Tories. When Butler pushed through reform on obscene publication law and the first curbs on immigration from the Indian subcontinent, he incurred the wrath of the Tory right and Labour supporters respectively, and three major crises would end up occurring that caused major damage to Macmillan’s government- the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ reshuffle (which Butler’s office leaked to the Daily Mail), the veto of British entry into the EEC, and the Profumo affair. Butler managed to remain distant from these, but relations between him and Macmillan subsequently became very cold, particularly as Macmillan started promoting people at odds with him such as Reginald Maulding (to Butler’s right economically) and Edward Heath (more pro-European than him).

Another major conflict arose when Macmillan was taken ill just before the 1963 Conservative conference. His three major favoured successors, and those of the parliamentary party, were Lords Home and Hailsham and Reginald Maulding. Butler, who was fond of none of these options (not least because neither Home nor Hailsham were MPs and Home had not even offered to seek the leadership), allegedly tried to urge Macmillan to stay on and avoid a constitutional crisis, especially given it would be the third major crisis of the year; ultimately, however, Home resigned his peerage (becoming Sir Alec Douglas-Home) and won a by-election in Kinross & Western Perthshire to become leader and Prime Minister.

Ultimately, Douglas-Home would do little to improve the faltering fortunes of the Tories; a few months after his election, the party lost a by-election in the safe seat of Dumfriesshire to Labour (now led by Harold Wilson after Gaitskell’s death), and famously lost Bury St Edmunds, Devizes and Rutherglen to Labour all in the same day in May 1964. Sensing that his odds of re-election in 1965 were poor, and given his relationship with Douglas-Home was poor, Butler ultimately decided not to seek a third term.

As if the Tories hadn’t had enough crises in the 1960-65 Parliament, one more hit them in late 1964, as Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith held an independence referendum that November which resulted in 90% support for independence. Despite the Commonwealth, UN and Labour all seeing the vote as illegitimate, Douglas-Home settled with Smith and Butler allowed Rhodesia to become independent, citing the consensus of the Victoria Falls Conference of July 1963 that led to Malawi and Zambia becoming independent.

The Tories hoped the controversy around this would wear off by the time an election had to be called, but ultimately it became a rallying point for Labour and a huge black mark on both Butler and Douglas-Home. Labour’s policy pledges, including sanctions on Rhodesia, socially liberalizing reforms and other policies popular with younger voters sick of the Tories after 12 years, made them far more popular and in tune with national popular opinion than Douglas-Home’s Tories, and 1965 would turn out to be a golden year for Labour…

(results by county close-up. I've changed the colour scheme since the Liberals are involved now, and the margins are consequently lower)

Last edited:

FIRST COME, FIRST SERVE!

An Alternate Election of 1920

November 2nd, 1920. The Great War was over, but there was still a looming menace. "Unpreparedness for war, unpreparedness for peace" cried the Republicans, while the Democrats prepared for a vicious battle to defend the Executive Branch from the Grand Old Party.An Alternate Election of 1920

Then the Republicans chose Leonard Wood. Wood, a friend of the recently-deceased Roosevelt, had the passion of the Bull Moose and the political experience of Zachary Taylor. Though only holding the executive office of Governor of Cuba, he was a charismatic politician. His vice presidential pick, the Governor of Illinois Frank Lowden, was a compromise devised from the stalling Republican National Convention.

The Democrats, trying to win back some support, elected President Wilson's son-in-law, William G. McAdoo. The incumbent executive, though half-paralyzed, was purportedly desperate to run for a third term, and was planning on denying McAdoo the candidacy; before this could occur, Wilson suffered from a nearly-fatal stroke, one of several during his presidency.

The only serious contender with McAdoo was Alexander Palmer, who was responsible for a massive crackdown on Anarchists and Reds--proclaiming that the American-styled Bolsheviks were out to coup the government during the tumultuous times of the Red Scare. When no such destruction of America came, the overwhelmingly authoritarian crackdown on leftist ideals came under scrutiny (while leftism itself was still despised in its many forms, the crackdown was far too much for many conservative Democrats to stomach), adding yet another nail to the coffin known as the Democratic Party in 1920.

On platforms, there were similarities between the two--both the Republicans (through Lowden) and Democrats were in support of prohibition, for example. There were many more differences, though. Wood was radical--his time in combat had given him a great respect to his African neighbors, and the GOP's platform included anti-lynching bills, the crime itself only being denounced by Wilson, with no policies banning the practice. In contrast, McAdoo had more or less exported Jim Crow laws out of the South--claiming, while Secretary of the Treasury, that the department needed segregation to prevent friction. McAdoo, for his part, was something of a progressive elsewhere--supporting a federal minimum wage and an eight-hour work day.

The election was nothing spectacular--the Democrats were pummeled to a pulp every state outside of the South--with Oklahoma and Tennessee both edging dangerously close to voting for the Grand Old Party, surprisingly. The Republicans won by a margin of around 10% in terms of the popular vote, and on March 4, 1921, Leonard Wood became the 29th President of the United States of America.

Flyer for General Wood during the Republican National Convention. Drafted before the compromise between Wood and Lowden,

there was reason to believe that a dark horse like Ohioan Senator Warren Harding could have won nomination.

-----

Last edited:

View attachment 595286

The 1960 British presidential election was the third election for the President of Britain, held on the 7th July 1960. Incumbent President Rab Butler, a Conservative, was running for re-election to a second term.

From the beginning, Butler was strongly favoured to win re-election, but despite this the Labour Party were eager to try and defeat him, not least because of rumours that if Butler were to win convincingly enough, Macmillan would take it as a sign to call a general election to try and bolster his small parliamentary majority.

It was also seen by Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell as an important opportunity to enact his authority by funding and endorsing the campaign of his favoured candidate, Anthony Crosland. Since the main opponent to Crosland from the left was Richard Crossman, the right-wing papers predictably joked that Labour’s parliamentary party was ‘cross-eyed’.

Overcoming the Bevanites was to prove surprisingly easy for Gaitskell on this occasion, though, given that Bevan himself was seriously ill (he would ultimately die the day before the election, which led to campaigning being ceased prematurely) and since he had split his supporters by advocating against unilateral nuclear disarmament. Consequently, Crosland won the nomination and proved surprisingly adept at unifying the party against Butler, though this only really managed to narrow his deficit in the polls rather than get him to the point of having a chance to beat Butler.

The big surprise of the 1960 election came from neither of the major parties, but from the Liberals, fighting their first ever presidential election campaign. From their small 6-seat grouping in the Commons, only one was convinced to run a presidential campaign: Mark Bonham Carter, MP for Torrington elected in a shock victory over the Tories in a 1958 by-election who held his seat narrowly at the general election held 4 months later. Bonham-Carter’s family were strongly involved with Liberal politics and he was himself a close friend of then-leader Jo Grimond, plus at 38 he was younger and more telegenic than Butler or Crosland. Thanks to all this, for the first time the Liberals felt able to mount a proper campaign. It certainly helped that they could accumulate many protest votes, and they benefitted far more from the view of the election as a foregone conclusion than Labour did.

Once the votes were counted, it was clearly a second blowout for Butler, who took 53.4% of the vote to 36.3% for Crosland (the poorest share for Labour in a national election since 1935), but Bonham Carter achieved a staggering 10% of the vote, the highest for the Liberals in any election since 1929. Even if it didn’t amount to any electoral gain, it was a huge morale boost for the Liberals.

The one silver lining for Labour, so it seemed, was that perhaps at least Bonham Carter had taken so much wind out of the Tories’ sails that Macmillan wouldn’t want to risk an election. This proved not to be the case- Macmillan did indeed call an election for the 8th September, impressing voters by his unflappable response to the Liberal surge. While the Liberals held their six seats and gained a seventh as Jeremy Thorpe took North Devon for the first time, the big news of the election was the Tories bolstering their majority from 24 to 106.

Almost immediately after these two major electoral victories, though, things started to go horribly wrong for the Tories. When Butler pushed through reform on obscene publication law and the first curbs on immigration from the Indian subcontinent, he incurred the wrath of the Tory right and Labour supporters respectively, and three major crises would end up occurring that caused major damage to Macmillan’s government- the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ reshuffle (which Butler’s office leaked to the Daily Mail), the veto of British entry into the EEC, and the Profumo affair. Butler managed to remain distant from these, but relations between him and Macmillan subsequently became very cold, particularly as Macmillan started promoting people at odds with him such as Reginald Maulding (to Butler’s right economically) and Edward Heath (more pro-European than him).

Another major conflict arose when Macmillan was taken ill just before the 1963 Conservative conference. His three major favoured successors, and those of the parliamentary party, were Lords Home and Hailsham and Reginald Maulding. Butler, who was fond of none of these options (not least because neither Home nor Hailsham were MPs and Home had not even offered to seek the leadership), allegedly tried to urge Macmillan to stay on and avoid a constitutional crisis, especially given it would be the third major crisis of the year; ultimately, however, Home resigned his peerage (becoming Sir Alec Douglas-Home) and won a by-election in Kinross & Western Perthshire to become leader.

Ultimately, Douglas-Home would do little to improve the faltering fortunes of the Tories; a few months after his election, it lost a by-election in the safe seat of Dumfriesshire to Labour (now led by Harold Wilson after Gaitskell’s death), and famously lost Bury St Edmunds, Devizes and Rutherglen to Labour all in the same day in May 1964. Sensing that his odds of re-election in 1965 were poor, and given his relationship with Douglas-Home was poor, Butler ultimately decided not to seek a third term.

As if the Tories hadn’t had enough crises in the 1960-65 Parliament, one more hit them in late 1964, as Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith held an independence referendum that November which resulted in 90% support for independence. Despite the Commonwealth, UN and Labour all seeing the vote as illegitimate, Douglas-Home settled with Smith and Butler allowed Rhodesia to become independent, citing the consensus of the Victoria Falls Conference of July 1963 that led to Malawi and Zambia becoming independent.

The Tories hoped the controversy around this would wear off by the time an election had to be called, but ultimately it became a rallying point for Labour and a huge black mark on both Butler and Douglas-Home. Labour’s policy pledges, including sanctions on Rhodesia, socially liberalizing reforms and other policies popular with younger voters sick of the Tories after 12 years, made them far more popular and in tune with national popular opinion than Douglas-Home’s Tories, and 1965 would turn out to be a golden year for Labour…

View attachment 595284

(results by county close-up. I've changed the colour scheme since the Liberals are involved now, and the margins are consequently lower)

Mark Bonham Carter?

Any relation to Helena Bonham Carter?

I'd say that's probably the case. The Bonham-Carters are IIRC cousins of the Asquiths.Mark Bonham Carter?

Any relation to Helena Bonham Carter?

Mark Bonham Carter?

Any relation to Helena Bonham Carter?

He is, yeah! I only found out when I was reading his Wikipedia page to make that wikibox though tbh.

Hughes Beats Wilson: A Different 1916 and beyond

Chapter III: Icarus

Chapter III: Icarus

The landslide victory of Representative John Nance Garner and Secretary of State Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1928

presidential election echoed the popularity of the McAdoo administration, and by extension, the Democratic party.

President McAdoo was enormously appealing with his handsome looks, obvious enthusiasm and boundless energy. He had an uncomplex personality that was always persuasive, optimistic and self-assured. What was lacking was depth or commitment to deep principles. He excelled as a maverick promoter and businessman who supported antitrust measures that were favored by the progressive movement. McAdoo left his mark on the United States's foreignand domestic policies, with major impact on the entire economy. In the 1920s, as his Democratic Party polarized he took the side of rural America, especially the South, as opposed to Al Smith's big cities. He never supported the Ku Klux Klan, but on the other hand refused to denounce it when so many loyal Democrats belonged.

In 1924, McAdoo won the Democratic nomination without serious opposition. The Republicans nominated General Leonard Wood, a popular war hero and progressive politician. The delegates chose James Wolcott Wadsworth Jr, a conservative Senator from New York as the Republican party's vice presidential nominee to appease the conservatives. The results of the election were never in doubt and McAdoo was handily reelected.

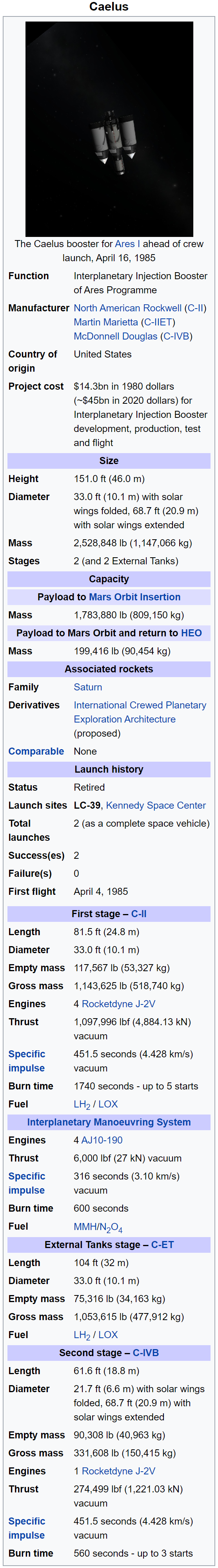

“When the time came to separate from Caelus main stage, a hush fell over the Command and Navigation Station. The switch, one we’d all been very careful around, was directly in front of us: ‘C-II SEP’. Rob lifted the cover and looked at us both. Wistfully, he pulled the switch, and pushed it down.

“There was a dull thud, and the sharp crack of reaction control thrusters as we separated. Two of us floated over to the windows in the mission module. The separation manoeuvre involved a few feet per second thrust forward, and a few degrees of yaw, so we could get a view of the booster. As we turned, the motors driving the solar panels whirred, keeping them facing the sun.

“It slid into sight slowly, yellowed and aged by the months of space flight. Just above the IMS pod, there was a small scorch, the only evidence of our twenty minutes of terror after the micrometeoroid collision. A whistle from behind me and a breathy curse. A camera clicked.

“The UNITED STATES, imprinted in red on the booster’s flanks, shone proud. I’m not afraid to say my lip wobbled, thankful for the reliability and hard work of the stout booster. Those four engines, their bells, wrapped in foil and shining in the sun, had got us into Martian orbit, and now, set us on our way home.

“The stage stayed in sight for about ten minutes, tumbling away. Every few minutes, there was a flash of RCS fire, moving it further away from us. I hung at the window until I couldn’t see the insulation glisten anymore. My eyes were moist. Next to me, a camera clicked.”

Find out more

The Skylab Programme here and here |The Saturn I+ | Saturn I+ Recovery - SL76B | Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 37 | Apollo SL82A Launch Abort, sometimes called Alabama's Hop | Mars Exploration Module Test Programme | Super Joe launch vehicle | KS-IVB Orbitanker Wikibox and Shipbucket | Judith Resnik

“There was a dull thud, and the sharp crack of reaction control thrusters as we separated. Two of us floated over to the windows in the mission module. The separation manoeuvre involved a few feet per second thrust forward, and a few degrees of yaw, so we could get a view of the booster. As we turned, the motors driving the solar panels whirred, keeping them facing the sun.

“It slid into sight slowly, yellowed and aged by the months of space flight. Just above the IMS pod, there was a small scorch, the only evidence of our twenty minutes of terror after the micrometeoroid collision. A whistle from behind me and a breathy curse. A camera clicked.

“The UNITED STATES, imprinted in red on the booster’s flanks, shone proud. I’m not afraid to say my lip wobbled, thankful for the reliability and hard work of the stout booster. Those four engines, their bells, wrapped in foil and shining in the sun, had got us into Martian orbit, and now, set us on our way home.

“The stage stayed in sight for about ten minutes, tumbling away. Every few minutes, there was a flash of RCS fire, moving it further away from us. I hung at the window until I couldn’t see the insulation glisten anymore. My eyes were moist. Next to me, a camera clicked.”

Find out more

The Skylab Programme here and here |The Saturn I+ | Saturn I+ Recovery - SL76B | Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 37 | Apollo SL82A Launch Abort, sometimes called Alabama's Hop | Mars Exploration Module Test Programme | Super Joe launch vehicle | KS-IVB Orbitanker Wikibox and Shipbucket | Judith Resnik

Last edited:

Bored, so I made a Qing victory against the tongmenghui, idk if add context due to the lack of sense.

Well guys, I just created a new creature infobox. I am going to add it tomorrow to go along with its Halloween theme. I'm not giving any other hints to what it is, it is just a creature that is normally associated with Halloween.

The 1965 British presidential election was the fourth election for the President of Britain, and was held on the 8th July 1965. It was the first British presidential election to be held on the same day as a general election to the House of Commons, a rare occurrence since the Presidency is elected to fixed terms while Parliament can be (and usually is) dissolved before the end of its five-year maximum term. Incumbent Conservative President Rab Butler chose not to run for a third consecutive term, leaving the presidency open.

Since Labour had a large lead in the polls for both the general election and the presidential election, the nomination process for the Tories was a fairly muted affair, with Chancellor Reginald Maudling being picked as the party’s nominee largely because of the vain hope his tax cuts during 1963-4 would provide enough of a boost to pull off the upset against Labour.

Maudling, however, was no match for Labour’s choice for President. Partly to placate the left, which had felt sidelined by the pick of Crosland in 1960, but also since she was a major advocate of decolonialism and due to the good working relationship they shared, Wilson threw his weight behind Barbara Castle in the party’s vote on their candidate in 1965. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the choice of a woman for President came in for sexist scorn from certain ranks of the Tories, but Castle was seen by most voters as a bold choice and proved an effective orator.

The Liberal campaign was not quite as spirited as it had been in 1960, but Mark Bonham Carter was persuaded to stand again nonetheless, this time largely prying off protest votes from the Tories rather than Labour. He admitted in his memoirs that he mostly stood to ensure he would retain a high public profile in order to avoid being easily targeted by the Tories in Torrington (which worked- he won by 6,822 votes, his highest-ever majority for either Torrington or West Devon).

Neither Wilson’s nor Castle’s majority was ever in any serious doubt, as while Wilson turned a 92-seat Tory majority into a 124-seat Labour majority, Castle took 55.8% of the vote to 37.1% for Maudling and 6.6% for Bonham Carter, making her the first woman and first Labour politician elected President of Britain. Not surprisingly, the mood among the left and many young Britons was jubilant, and remained so for a while- under Castle and Wilson, the government enacted firm embargoes on Rhodesia and South Africa and condemned their regimes, famously recognized youth culture by giving MBEs to the Beatles, and nationalized the steel industry.

But like most waves of popularity for governments, and especially with the tumultuous nature of the 1960s, this did not last. Devaluation caused significant damage to the British economy, Labour quickly split over joining the Common Market and its efforts to do so were vetoed by the French anyway, and Wilson made himself unpopular by providing moral (though not military) support to US President Johnson for the Vietnam War.

To her credit, Castle did a better job of avoiding backlash for a lot of this both by even more vociferously condemning the US’s actions in Vietnam than did Wilson, and intervening in support of the women of the Ford Dagenham plant when they went on strike in 1968, finding solidarity with them due to her experiences of discrimination in the Commons and institutional prejudice in Buckingham Palace.

The latter case not only provided useful leverage for Castle’s popularity, but also gave her and Wilson a precedent to arrange the ‘In Place of Strife’ industrial relations policy, perceived by critics as seeking to undermine trade unions, but which Castle ultimately successfully sold as simply seeking to democratize them with mandatory ballot measures. While Labour was split on the issue, it did manage to get the policy signed into law, though its provisions for the establishment of an Industrial Board to enforce settlements would not come to fruition until several years later after later labour relations acts.

In the Opposition, much had changed: Douglas-Home was out by the end of 1966, but the main contender for the leadership, Edward Heath, was out of contention having lost his Bexley seat to Labour. In his absence, the Tories had to settle for Quentin Hogg, formerly Lord Hailsham, given most of the other obvious choices to succeed Home like Maudling or Iain Mcleod were not realistically in a good position to lead (Maudling having lost the 1965 presidential race and Mcleod having vocally refused to serve under Douglas-Home and opposed him on Rhodesia, angering the Tory right).

Hogg, however, was nowhere near as effective a rival to Wilson as Heath might have been (and he didn’t even try to return to Westminster, deciding to give up politics to pursue his sailing hobby instead after the 1965 election), and Labour ended up losing by-elections to the newly strengthening Scottish and Welsh nationalists, the SNP and Plaid Cymru, and the Liberals as much as the Tories. Consequently, in 1969, just prior to ‘In Place of Strife’ being introduced that summer, Wilson called a general election to try and avoid suffering too many losses; Hogg only managed to slash Wilson’s majority from 106 at dissolution to 54, and consequently became the first Tory leader since Austen Chamberlain to leave the party leadership without ever becoming Prime Minister.

The battle for his successor would be a hard-fought one, and the Tory party ultimately decided amongst itself one of the men battling for the parliamentary leadership was more suited to a presidential role, not least for his commanding and populist (if divisive) rhetoric. The other, while more moderate, was also a darling of the right and an advocate of what would come to be known as ‘monetarism’. The two of them would oversee the beginning of a dramatic transformation of the Conservative Party…

(results by county close-up)

Last edited:

A talking pumpkin?Well guys, I just created a new creature infobox. I am going to add it tomorrow to go along with its Halloween theme. I'm not giving any other hints to what it is, it is just a creature that is normally associated with Halloween.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: