Hopefully the qing will make some new invention ITTL to help the people so they will at least be remember for something good.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Destiny Realized: A Timeline of Afsharid Iran and Beyond

- Thread starter Nassirisimo

- Start date

-

- Tags

- iran islam persia persia wank

Threadmarks

View all 59 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Political Culture and Society in Iran - 1831 to 1846 The Third Revolutionary Wars - Europe 1832 to 1838 Changing Tides - The Middle East 1832 to 1844 India - 1831 to 1856 Iranian Society under the Afsharids - 1800 to 1847 The Second Great Turkish War - 1845 to 1849 Growing Vulnerabilities - East Asia 1831 to 1857 The Mahdist Uprising in Fars - 1848 to 1852Well first off allow me to apologise for the delay in a proper update. Real life has been

keeping me rather busy, but the next update is in the works and will be posted next weekend at the very latest.

Even provided that China finds the will, that doesn't necessarily provide the means. The late 18th century saw defeats in a number of conflicts for the Qing in OTL as well as in the timeline, particularly when facing off against her Southeast Asian neighbours. Although China is invulnerable to her neighbours for the time being, it doesn't follow that China is guaranteed victory in any conflict against them, and she is constrained by the same logistical challenges that everyone else in the world is.

This isn't to mean that China is doomed however. Over a century of comparatively good rule leave the Qing in good stead, and China is still an absolutely enormous whopper of a country. At this point her population is almost ten times that of her nearest competitor considering the fact that India is divided.

keeping me rather busy, but the next update is in the works and will be posted next weekend at the very latest.

Thanks, that should be fixed now. I really need to keep an eye on these things...The last updates haven't been threadmarked.

Thing is, although the internal situation for China may be somewhat better without opium flooding the southern provinces, China isn't going to get the shock to her system that she suffered during the opium wars of OTL, at least not at the same time. Taking away one of the main impetus for reform won't be making China go on a spree of conquest.I have a small request: that the Qing do similar reforms to what the Song Dynasty did.

Just look at this (look at first 2 answers, third one is a bit too short to be useful):https://www.quora.com/Did-the-Song-...-were-the-noteworthy-achievements-of-the-Song

Also, doing all of those reforms would not only strengthen China (which already has a third of global economy), but make the Manchu rulers popular. Besides, they could use the steam engine which the Song nearly made to catch up to the allies.

Also, China should annex Vietnam, Hokkaido, and the land around lake Irtusk. Especially all of Vietnam, and when the get Vietnam, they should start producing Vietnamese rifles, which were some of the best in the world in the 18th century but would likely be OK by early 1800 standards

Maybe the Qing can survive and look like this:https://vignette.wikia.nocookie.net...a_today.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20091105060119

Even provided that China finds the will, that doesn't necessarily provide the means. The late 18th century saw defeats in a number of conflicts for the Qing in OTL as well as in the timeline, particularly when facing off against her Southeast Asian neighbours. Although China is invulnerable to her neighbours for the time being, it doesn't follow that China is guaranteed victory in any conflict against them, and she is constrained by the same logistical challenges that everyone else in the world is.

Be quite interested how the Screamble for Africa will look this time around now that it's more islamicised in the eastern portion of it.

It's entirely possible that it will be avoided, especially if there are stronger states in Africa with access to more modern weaponry. The Islamic States of the Sahel may have trouble if a European power has the means and will to break into the interior, but it is worth considering that even in OTL, the Sokoto Caliphate held out until 1903. African States will find it very difficult to keep up to the Europeans in terms of naval strength, but away from the coast they have more of a fighting chance.It could just not happen at all. It took a very specific set of factors from the 1850s onward to cause it anyway.

The internal troubles of China have most likely not been averted, considering that the population has skyrocketed as it did in OTL. The Qing also have to contend with the fact that at the end of the day, they are conscious foreigners ruling over hundreds of millions of "others". As long as the Han Intelligentsia is kept on side, this won't be a problem but as China's problems mount, this may not remain the case going forward.To be fair though, there hasn't been a huge amount of butterflies when it's come to the Qing. Not too much reason why history would diverge there to a huge extent, at least until the 1830s when the Century of Humiliation would've started (lacking European domination of India will likely preempt the Opium Wars). Reforms aren't great for stability either and, while technological advances will march forward, there won't be as much of an effort to accelerate military+naval tech and equipment in relation to OTL, where the Qing were forced to modernize their armies (actually besting the French on land and outgunning the Japanese at sea. Not that that did too much for the Sino-Japanese War but that was the case). If anything though, the Qing should be in a worsening situation, with the White Lotus Rebellion, Eight Trigrams uprising, Miao Rebellions, etc. (all within 10 years of 1800) shaking the Qing's stability and inciting more unrest against the Manchu.

As for annexing Vietnam, that probably would cause even more issues, seeing as how Chinese invasions of Vietnam over the last millennium haven't gone too well.

This isn't to mean that China is doomed however. Over a century of comparatively good rule leave the Qing in good stead, and China is still an absolutely enormous whopper of a country. At this point her population is almost ten times that of her nearest competitor considering the fact that India is divided.

and Africa likely develops more and isn't as corrupt, I'm guessing

I mean corruption will always be there, but if strong native institutions are allowed to develop, you could have more of the continent looking like Botswana rather than the Congo.Cut the colonization and you get both of those with no extra cost.

At the dawn of the 19th century of OTL, Iran was a shrunken half-nomadic country having come out of a near-century of civil war and disruption. While the threat of Europe is beginning to loom, some perspective vis-a-vis OTL should be kept and with that in mind, Iran looks to be in a much better position than she was. Her population is more than twice the size, her borders are far more expansive, her population more settled, her cities larger and a great deal more trade goes through. The storm is coming but Iran may be able to rely on more than just playing European powers off of each other.Why do I have a sinking suspicion TTL's Iran's 19th century is going to be a lot like OTL Iran's 19th century?

The Congo got a handful of university graduates and some paved roads upon independence, for a country slightly over half the size of European Russia. The trade off of millions of Congolese lives (and hands) during the height of the Free State was therefore a good one apparently.What are you talking about? Colonization was key to developing Africa! Don’t you know that skulls make excellent building materials?

Don't worry, the 19th century will not be a repeat of the previous iteration's 19th century or our own.i hope not, it would rather undermine the point of the AH if it just ends up sticking to historical rails like the last version did.

Personally I think that the Qing should be fairly well remembered as far as Chinese dynasties go. More than a century of internal stability, unprecedented territorial expansion and internal economic growth should be appreciated.Hopefully the qing will make some new invention ITTL to help the people so they will at least be remember for something good.

markus meecham

Banned

I feel that that post was ironic.The Congo got a handful of university graduates and some paved roads upon independence, for a country slightly over half the size of European Russia

While i am pretty sure that there are many apologists of imperialism over here, i don't think any of those has the balls to defend leopold.

With a GDP per capita of Botswana, Africa would have a full democracy (or have all democracy nations), a total nominal GDP of 9 trillion, and a GDP PPP of 23 trillion.

Also, is it possible for you to give us a list of all the populations of the major countries?

Also, Leopoldo can burn in hell, I prefer Stalin and Mao over him.

Also, is it possible for you to give us a list of all the populations of the major countries?

Also, Leopoldo can burn in hell, I prefer Stalin and Mao over him.

I feel that that post was ironic.

While i am pretty sure that there are many apologists of imperialism over here, i don't think any of those has the balls to defend leopold.

Yeah. I thought saying skulls were good building materials made that clear...

I'd certainly say that the post was ironic. Leopold is one of the more prominent murderous colonialists, and probably the among the most brutal when it came to squeezing as much money as he could from his territory, though the Scramble for Africa is unfortunately chock-a-block full of some of the most reprehensible characters in history.I feel that that post was ironic.

While i am pretty sure that there are many apologists of imperialism over here, i don't think any of those has the balls to defend leopold.

Economic development doesn't necessarily mean democracy. In our own world, Thailand is more prosperous than Indonesia, yet Indonesia is unquestionably more democratic (at least these days). Likewise Tunisia, the only democratic Arab country, is among the poorer ones. What economic development does often lead to is the development of civil societies. The prospect of an Africa as a serious economic area is pretty tantalising though.With a GDP per capita of Botswana, Africa would have a full democracy (or have all democracy nations), a total nominal GDP of 9 trillion, and a GDP PPP of 23 trillion.

Also, is it possible for you to give us a list of all the populations of the major countries?

Also, Leopoldo can burn in hell, I prefer Stalin and Mao over him.

I'll write a list in the next post, just to give a bit of an indication where things stand in 1800.

There probably is some corner of the internet which idolises Leopold for his genocide in the Congo unfortunately.Yeah. I thought saying skulls were good building materials made that clear...

This post isn't quite an update, more a list of the various powers of the world organised by population. Generally speaking population figures include both colonies and the metropole and will inevitably be a bit inaccurate here and there. Some countries do not differ too much from OTL where as for others (like Iran) there is a pretty noticeable difference. There will be some notes to explain in detail.

Iran: 18,810,000 (Our main star of the show, compared to the Iran of OTL the population is enormous, our own Iran had a population of about 6 million at this time.

Ottoman Empire: 22,300,000

Morocco: 3,490,000

Algeria: 2,630,000

Tunisia: 1,280,00

Marathas: 24,680,000

Mysore: 18,800,000

Awadh: 22,772,000

Bengal: 35,604,000 (Bihar is also a part of Bengal, and Biharis make up a sizeable chunk of this population)

Sikh Empire: 7,750,000

China: 297,000,000

Japan: 29,000,000

Korea: 16,500,000

Great Britain: 22,000,000 (still including the North American Colonies of course)

France: 26,000,000

Russia: 28,000,000

Spain: 24,000,000

Portugal: 9,270,000

Austria: 27,845,000

Brandenburg: 2,640,000

Sweden: 4,832,000

Denmark: 3,010,000

Poland: 16,809,000 (It's a bit less imposing than its population would suggest of course)

Naples: 6,700,000

Zanzibar: 1,184,000 (This isn't too impressive at the moment, but things may be about to change)

Vietnam: 5,960,000

Siam: 1,652,000 (Limited to parts of the Chaophraya Basin and adjacent areas, this is likely to grow rather swiftly as the new Thai regime finds its feet.

Cambodia: 1,120,000

Burma: 5,156,000

Iran: 18,810,000 (Our main star of the show, compared to the Iran of OTL the population is enormous, our own Iran had a population of about 6 million at this time.

Ottoman Empire: 22,300,000

Morocco: 3,490,000

Algeria: 2,630,000

Tunisia: 1,280,00

Marathas: 24,680,000

Mysore: 18,800,000

Awadh: 22,772,000

Bengal: 35,604,000 (Bihar is also a part of Bengal, and Biharis make up a sizeable chunk of this population)

Sikh Empire: 7,750,000

China: 297,000,000

Japan: 29,000,000

Korea: 16,500,000

Great Britain: 22,000,000 (still including the North American Colonies of course)

France: 26,000,000

Russia: 28,000,000

Spain: 24,000,000

Portugal: 9,270,000

Austria: 27,845,000

Brandenburg: 2,640,000

Sweden: 4,832,000

Denmark: 3,010,000

Poland: 16,809,000 (It's a bit less imposing than its population would suggest of course)

Naples: 6,700,000

Zanzibar: 1,184,000 (This isn't too impressive at the moment, but things may be about to change)

Vietnam: 5,960,000

Siam: 1,652,000 (Limited to parts of the Chaophraya Basin and adjacent areas, this is likely to grow rather swiftly as the new Thai regime finds its feet.

Cambodia: 1,120,000

Burma: 5,156,000

Wow. Mysore is absolutely massive. Even IOTL, it’s just miraculous how it went from an irrelevant city state until about the 1670s to one of the strongest Indian states by the 1770s. In that regard, it’s like the Prussia of India (except that it was conquered eventually). ITTL, with Madras in its grasp...

@Indicus who knows, maybe Mysore can industrialize, become rich (about 10% of the global economy), become liberal monarchy, and conquer all of India, or just rule Southern India as an Industrial powerhouse.

@Nassirisimo Population of China is a wee bit small IMO, I thought it was 400 million at this time.

@Nassirisimo Population of China is a wee bit small IMO, I thought it was 400 million at this time.

Will we get a Union of Iranian/Asian Socialist Republics?Don't worry, the 19th century will not be a repeat of the previous iteration's 19th century or our own.

Of the start of the 19th century? Damn those butterflies really flappedGreat Britain: 22,000,000 (still including the North American Colonies of course)

EDIT: Or do you just mean the Caribbean colonies + the Canadas?

Didn't France keep Canada TTL? Doesn't the UK still have the 13 Colonies?Of the start of the 19th century? Damn those butterflies really flapped

EDIT: Or do you just mean the Caribbean colonies + the Canadas?

The fact that Mysore was conquered has been a shame in historiographic terms, as one of the most dynamic states in any part of the world in the 18th century has been relatively forgotten. Its army was technologically ahead of the Europeans in some aspects, its economy was thriving and it was fairly well led. Here of course, Mysore has been able to conquer Travancore and more, and is unquestionably the dominant state in South India. Hyder Ali was really underrated, and achieved an impressive amount for an illiterate soldier-of-fortune, rather like another important figure in this timeline.Wow. Mysore is absolutely massive. Even IOTL, it’s just miraculous how it went from an irrelevant city state until about the 1670s to one of the strongest Indian states by the 1770s. In that regard, it’s like the Prussia of India (except that it was conquered eventually). ITTL, with Madras in its grasp...

What may hold Mysore back in terms of industrialisation may be a lack of coal. The coal deposits of South India tend to be poor-quality lignite, but perhaps Mysorean factories could be powered by water, and then by coal imported from elsewhere in India and beyond. Bengal has large, if hard to access coal reserves.@Indicus who knows, maybe Mysore can industrialize, become rich (about 10% of the global economy), become liberal monarchy, and conquer all of India, or just rule Southern India as an Industrial powerhouse.

@Nassirisimo Population of China is a wee bit small IMO, I thought it was 400 million at this time.

In regards to China's population, I'd previously been under the impression that Qing China's population was around the 400 million mark too, but the government census describes the population as being around 333 million in 1812, making the figure mentioned in the mini-update a bit more realistic.

Perhaps if we do, they would be threatened by some kind of Fascistic Genocidal Turkey. Alternate history should rhyme as much as Star Wars does.Will we get a Union of Iranian/Asian Socialist Republics?

Of the start of the 19th century? Damn those butterflies really flapped

EDIT: Or do you just mean the Caribbean colonies + the Canadas?

France has Quebec and Britain retains the 13 colonies. For now...Didn't France keep Canada TTL? Doesn't the UK still have the 13 Colonies?

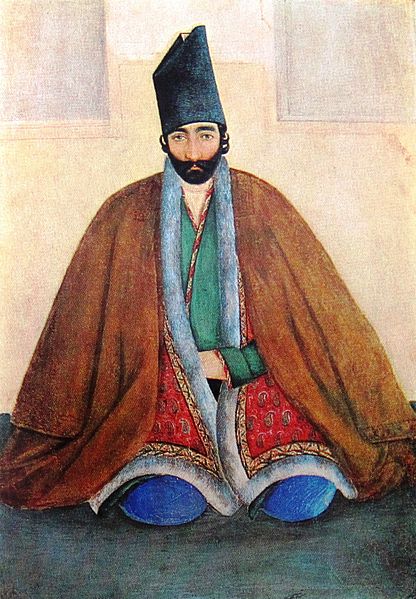

Iran in the Reign of Emam Shah - 1805 to 1819

Prince Emam Qoli, before his enthronement as Shah.

The Rise and Reign of Emam Shah

At first glance, the downfall of the Safavid Dynasty and the period following the overthrow of Shahrukh Afshar mirror each other. Both saw a period of weak central control follow on from the downfall of an ineffective monarch, and a subsequent reunification of the country by a more powerful figure. There the parallels end however, as there was far more which differentiated the two times. Firstly, the decade that followed the fall of Isfahan brought foreign occupation and mass depopulation to Iran, which had not taken place following the overthrow of Shahrukh. Secondly, while Nader Shah followed up his reunification of Iran with a sequence of brilliant conquests abroad, Emam Shah did no such thing when he marched into Mashhad and revived the Afshar State, instead preferring to further consolidate the existing borders of the country. This reflected a different kind of mind-set on the part of Emam, as well as a recognition of the changing situation which Iran found itself in. Iran was now surrounded by stronger neighbours, most of whom had absorbed the harsh lessons given by Nader Shah and his successors.

Emam Shah’s enthronement came at the end of a generational cycle of overthrows, coups and general disorder thorough Iran. Although this period of disorder had not been as severe as that which had followed the Fall of Isfahan and the Safavid Dynasty, it had nevertheless taken its toll on the Afsharid state. In outlying areas, the emphasis on the implementation of a centrally-controlled bureaucracy unaccountable to local power-brokers was now replaced with a renewed appreciation for existing conditions on the ground. While the idea of an Iranian State which encompassed the area from China to the Ottoman Empire in a common set of laws and rulers was certainly not a thing of the past, the intensity of the centralising efforts of the government certainly lessened from the time of Emam Shah. While Iran remained as a comparatively centralised state, which the majority of revenues going to the central government, there was an increasing tendency for taxation raised on a provincial level to be spent at the provincial level. In outlying provinces such as Fergana and Dagestan, local princes and Khans were ever more important to the governance of said provinces, marking a reverse from the practices of Nader and Reza in that the provincial traditions of governance were generally eroded.

In parts of the Empire, this led to an improvement of the security situation. As regional potentates were brought into the structure of the Afsharid State, there was generally less temptation to harass agents of said state and to cooperate with enemies of the state. Although there was no question of a return to a system of subject Khanates that had prevailed prior to the reforms of the early Afsharids, this demonstrated a level of flexibility among the rulers of Iran that had not existed previously. As well as benefits to the central state however, the new system also brought increasing challenges, particularly in majority Christian areas. Although the largest Christian population of the Empire, the Armenians, tended to be geographically dispersed, there were some (such as the Georgians) who tended to be concentrated in regions with a heavy Christian majority [1]. As Georgian nobles and princes became more important in the governance of the province relative to Iranian bureaucrats, there were the beginnings of a Georgian “Renaissance” as a newly re-empowered Georgian elite patronised art and literature.

What the lessened emphasis on centralisation betrayed was that Iran was far from a “natural” state, but was rather a composite empire of disparate regions. While there was a central “crescent” of relatively dense settlement from the area around Tabriz and Yerevan to the Central Asian cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, this area was far from a homogenous core. Around half of the population was Persian-speaking, with much of the rest being a mix of Turkic and Iranian peoples [2]. The area was mountainous and even in the crescent there were vast areas of desert in which agriculture was a near-impossibility. Compared to the productive cores of other empires, this was not particularly promising. Otherwise, the outlying areas of Iran seemed to gravitate economically and in some sense culturally toward other empires. Mesopotamia’s trade and cultural links with Syria and the Gulf were just as important as its links with the central Iranian cities of Hamadan and Kermanshah. The Persian Gulf was more integrated into the growing Indian Ocean trade network than it was to Central Iran. Without the emphasis on a standardised bureaucratic system, the progress of cultural integration in these outlying regions was halted.

In what sense did the new Iranian system initiated by Emam Shah represent a break from the “Naderian” system that had characterised the Iranian state since the rise of Nader Shah? Certainly in terms of military ambition, Emam Shah seemed perfectly content to focus on defence, building a number of fortifications throughout the country and more firmly than his more illustrious predecessors seeking peace with his powerful neighbours. Yet this did not entail the abandonment of a professional standing army, which although somewhat smaller than in Nader’s day (around 180,000 soldiers were on the rolls in 1811 for example), and the Iranian navy remained as a significant force in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea. And whatever steps had been taken away from the centralisation of power in the hands of the Shah, Iran remained far more centralised than it had been under the Safavids.

Rather than a radical break with the early Afsharid state, Emam’s rule and the changes he made to the system should be seen within the context of Reza Shah and Nasrollah’s reigns. Emam attempted to cut down the costs of imposing a standardised bureaucratic system on areas distant from the centre in Khorasan. Rather than conquest, Emam looked toward cooperation with neighbouring rulers, though tensions with his Russian neighbours remained high thorough his reign. A greater conqueror he may not have been, but as the Scottish writer James Baillie Fraser noted,

In the majority of Iran, the peace and tranquillity afforded by the rule of the Shah, as well as his general aversion to warfare where possible as gained him the affection of many in the country. His reputation for the administration of justice is a well-earned one and has further contributed toward his esteem in the eyes of his people.

Although pride could be inspired through great victories as Nader had done, a more reliable way to gain the admiration of one’s people in a pre-modern era was to, as Emam Shah had done, simply provide peace and a measure of justice without imposing excessive taxation.

[1] – Although the population of the Armenian Highlands is about half Armenian roughly, there are a great number of Armenians outside this. With communities stretching from Poland to Malaya, the Armenians are on the fast-track to being one of the great mercantile peoples of the world even more so than OTL.

[2] – As well as Turkic peoples such as the Afshars and Qajars in "Old Iran" itself, there are Turkmen, Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in the empire, as well as millions of Oghuz Turks who we know in OTL as Azeris.

* * * * * *

“Toward an Impossible Goal – The Growth of Trade in Early 19th Century Iran”

“Toward an Impossible Goal – The Growth of Trade in Early 19th Century Iran”

Despite the safety of its roads, its strategic location between Europe and the rich lands of China and India, as well as its own bustling cities full of artisans, trade in Iran was always a difficult proposition prior to modern times. The rugged nature of its land, the absence of major rivers and the vast distances through the country precluded the development of a “national market” as seen in other countries. Although good governance on the part rulers such as the Safavid Shah Abbas or the Afshar Reza Shah had helped foster long distance trade to some extent, the costs of sending goods across the country precluded the development of a national market. Due to the enormous costs of transportation, long distance trade tended to be limited to a number of goods with a high value to weight ratio such as manufactured textiles, spices and silk. What trade did exist in other goods tended to be oriented outside of Iran rather than to other parts of the country. Indeed, one textiles merchant based in the Mesopotamian town of Raqqah bemoaned that it was cheaper to send goods to Marseilles than it was to send them to Hamadan.

Despite the difficult conditions and the near-impossibility of creating a truly national market, Iran nevertheless saw the growth of trade in the earlier part of the 19th century. Much of this was based on external trade, as the increased silk production of the Caspian provinces found a growing market in Russia, spices such as saffron were exported both across the Indian Ocean and into Europe, and pearls from the Persian Gulf found ready markets across much of the world. The volume of trade in Iran rose comparatively slower when compared to many other areas of the world, and this is due in large part due to the difficult conditions found in the country, but nevertheless Iran also found itself as a point of transhipment between Russia and India, pocketing a good deal of the goods, gold and silver that went between the two. Although profitable at times, this trade tended to be disrupted in the event of war with Russia, and was not always a reliable earner of cash for the Iranian government.

One of the main differences that had marked Iran’s external trade in the Afsharid era when compared to that of the Safavids was the relative importance of European merchants in Iran’s trade with Asia. Dutch and English merchants, and Portuguese merchants before them, had played a critical role in importing goods into Iran’s southern ports from elsewhere in Asia. However, since Nader’s creation of a real Iranian navy and his conquest of a number of important ports on the Arabian Peninsula, merchants who were subjects of the Iranian Shah quickly grew in importance. By 1800, the vast majority of merchants operating in Basra, Bushehr and Bandar Abbas were Iranian subjects, for the most part Arab in language and culture but with a significant number of Persians and Armenians. Iranian merchant houses were operational as far away as Cambodia, and Iranians were some of the first foreign merchants to operate in Siam following the restoration of order under the Chakri Dynasty [3].

[3] - As mentioned in the last update of Southeast Asia here, the younger brother of OTL's Rama I has established his own dynasty. Siam is certainly less of an economic power than she was at this point in OTL, but peace at home means expansion, and Iran may be well placed to gain a source of lots of scrumptious rice as shipping technology improves and the Chaophraya Basin is cultivated.

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - Iran is beginning to show the strains that come with trying to administer an enormous country in pre-modern times. The strain of holding such a large country together is not helped by the difficult terrain of Iran and its lack of navigable waterways around the core areas, though while this presents problems for the integration of the economy as seen in the second part of the update, this doesn't necessarily mean that it will end with a break-up of the country. The Persian Language and culture still remain as powerful centripetal forces, and even influence the otherwise-proud Turkic elements of the Empire. Whether these and other factors will provide enough "glue" to keep Iran together as the 19th century rolls on remains to be seen, but it is worth keeping in mind that despite her much larger size, Iran isn't necessarily more unwieldy and disunited than her OTL equivalent. The portion of the nomadic population is similar across the empire overall, but there are great Persian-speaking cities in some of the new areas (most of the great cities of Central Asia were Tajik Persian-speakers until the 20th century in OTL) from which Iranian culture can radiate out from. In addition to this, concentrated Christian populations are relatively rare.

Although the largest Christian population of the Empire, the Armenians, tended to be geographically dispersed, there were some (such as the Georgians) who tended to be concentrated in regions with a heavy Christian majority [1]. As Georgian nobles and princes became more important in the governance of the province relative to Iranian bureaucrats, there were the beginnings of a Georgian “Renaissance” as a newly re-empowered Georgian elite patronised art and literature.

Be interesting to see if the Amernians and Georgian's will have a 'National Awakening' in the vein of OTL Name an ethnic group in Rumelia, and how it will affect Russo Persian relations in the future.

As mentioned in the last update of Southeast Asia here, the younger brother of OTL's Rama I has established his own dynasty. Siam is certainly less of an economic power than she was at this point in OTL, but peace at home means expansion, and Iran may be well placed to gain a source of lots of scrumptious rice as shipping technology improves and the Chaophraya Basin is cultivated.

Even if the next update isn't centered on Southeast Asia, I am keen for the update.

There should be an updated map in this post. There's a link to a bigger version of the map on the post too.Can we get an updated map anytime soon?

Russia already has her eyes south, and may see the potential in a strategy of working with local Christians to achieve their geopolitical goals in the region. This would be bad news for Iran, but so long as the Caucasian Frontier holds, Russia's ability to make mischief in most of Iran will be limited.Be interesting to see if the Amernians and Georgian's will have a 'National Awakening' in the vein of OTL Name an ethnic group in Rumelia, and how it will affect Russo Persian relations in the future.

Even if the next update isn't centered on Southeast Asia, I am keen for the update.

Southeast Asia will be a few updates down the line, but rest assured some pretty interesting things will happen there. It could even be a two part update at this point.

I mean, we are in the 19th century now so Iran may well buck the trend. The Chinese Empire largely kept its territorial integrity and they were in an awful position for much of the 19th century in OTL.Please Iran, don't split!

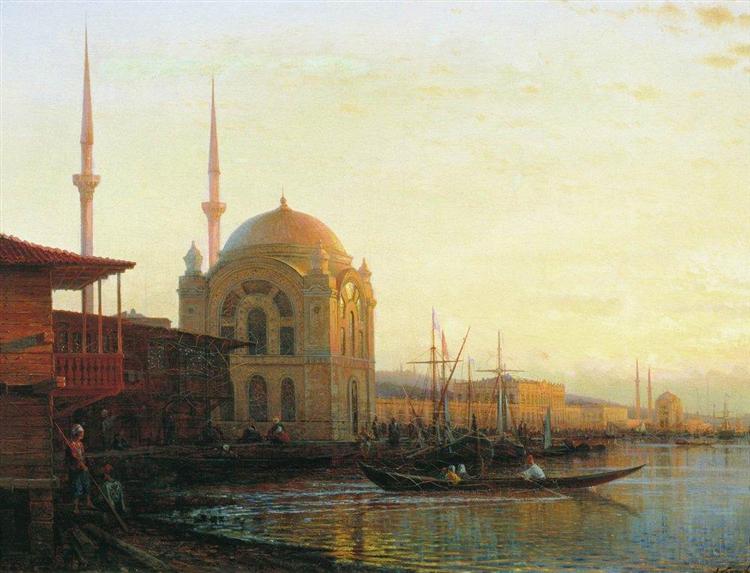

Crisis to Crisis - The Ottoman Empire 1804 to 1830

The Ottoman Empire and its External Relations 1804-1830

The position of the Ottoman Empire by the dawn of the 19th century was somewhat ambiguous. In the Middle East it had managed to see off the threat of the Wahhabi Movement, yet this had been done only through cooperation with their Iranian rivals, and had not led to a restoration of the Status Quo, but rather to a unique sovereignty-sharing agreement with the Iranians. This had represented a blow in terms of the Ottoman Empire’s prestige within the Muslim world, and was followed by the “Concorde of Aleppo” with the Iranians, which removed much of the ambiguity of the relationship between the two. International Historians have long compared to document to the Treaty of Westphalia, in that the sovereignty of both the Ottomans and the Iranians within their own borders was confirmed, and the Iranian Shah was confirmed as a “Caliph” as well as the Ottoman Sultan. This mutual recognition on the part of two Islamic Sovereigns of their claims to the Caliphate reflected the relatively low importance of the institution by the early 19th century [1].

For an Ottoman Empire which had been struggling to improve its prestige among its fellow Muslim powers, the Concorde of Aleppo seems to be something of a setback. It was the latest in a list of treaties with the Iranians which recognised equality between the two rulers, something which had been particularly anathema to the Ottomans previously. However, this does not necessarily mean that the treaty was disadvantageous or a bad idea on the part of the Ottoman Sultan. The primary objective was both to confirm the situation in Arabia and avoid future misunderstandings in the area, but also to provide both powers with one quiet border, which was of particular importance as the Ottomans had to contend with the growing power of the Austrians, the Iranians with that of the Sikh Empire, and both with the ever-expanding Tsardom of Russia. Although the ideological pan-Islamic element of the treaty was exaggerated by later historians and ideologues, numerous sections of the treaty do seem to suggest that part of the reason for this improvement of relations between the two was based on their common Islamic religion. The fact that previous accusations of heresy toward the Iranians seemed not to feature so heavily suggest that the “Jafari’ Madhab” was increasingly accepted by this point.

If the relations of the Ottomans toward their main Muslim rival were improving in this period, what then of their relations with their European neighbours? While many amongst the elite of the Ottoman Empire continued to hold hostile attitudes toward the Christian Europeans on a religious basis, there was also a realisation of the Ottoman Empire’s diminished strength vis-à-vis the Europeans. The loss of Crimea in particular had shocked the Empire, and had even given regional elites in far-away provinces an indication of just how much the danger from Europe had grown. The traditional good relations of the Ottomans and the French had been weakened by Ottoman ambiguity during the French Civil War (helped along by Ottoman misunderstandings of what the French Revolutionaries actually stood for) left the Ottoman Empire relatively isolated on the European diplomatic stage. Thus the Ottomans found themselves standing against Britain alone when the British undertook military action against the Dey of Algiers in response to an increase of slaving raids from the Ottoman province. The central Ottoman government stood aside as the British shelled and then occupied the cities of Algiers and Oran.

Although far from a decisive conquest, the “Algerian Action of 1806” as it came to be known by the British indicated the military, and in particular naval weakness of the Ottoman Empire. Although other European powers could similarly sympathise about the seeming invincibility of British naval power, there was nevertheless a great disquiet within the Empire that Ottoman Territory, albeit a highly autonomous Vilayet, was attacked and occupied in part with little response on the part of the Porte. Among the Ayan (notables) of the Empire, there was a fear that if they were to come under attack from European powers, then there would be a weak response from the Porte in their defence. Centrally, the question was whether the correct answer was to abandon provinces that could not be reliably controlled from Constantinople, or whether the army and navy of the Empire needed to be strengthened in order to reliably combat threats from European powers. For the regional notables already paying far higher taxes to the Porte than had been the case fifty years ago, this was not welcome news.

[1] - There is actually precedent for this. Even in OTL, one of Nader's goals was nothing less than the upending of a traditional Muslim assumption regarding statecraft, which held that different Islamic states could only be legitimately separated by oceans, which needless to say wasn't widely followed in OTL. In addition to this, one had leaders in parts of the Muslim world such as Diponegoro claiming the title of Caliph while not necessarily disputing the Ottoman claim.

* * * * * *

Internal Reform in the Ottoman Empire

Internal Reform in the Ottoman Empire

In many respects, the reform and internal development seen across the Ottoman Empire in the first part of the 19th century was a continuation of that seen toward the end of the 18th century. The government continued to build on previous reforms that aimed to centralise the revenue system of the empire and assert the authority of the Porte in all corners of the empire. In other respects however, the period also saw the introduction of new ideas and institutions, many of which were based on those found in Europe by Turkish travellers. In this sense, the development of the reform movement within the Ottoman Empire began to diverge from that of their neighbours in Iran. By the 1830s, the Ottoman administration was far more consciously attempting to “Westernise” rather than simply reform. This was testament not only to the growing awareness of the threats and opportunities that Europe presented, but also due to the increasing level of ideological flexibility among the empire’s elite, both in the centre and to an increasing extent, in the provinces.

The first part of the 19th century saw a continuation of the move away from the malikane tax farming arrangements towards other systems such as the esham which allowed the central government better access to the revenues of the land, as well as encouraging greater investment in the land itself. Particularly in Anatolia and the Arabic-speaking provinces of the South, the era saw an increase in irrigation and a move toward the production of cash-crops. Syria saw raw cotton production increase by 140% in the period of 1790-1830, buoyed by an increase in demand from the newly industrialising countries of North-Western Europe. However, it was the well-watered Nile Valley of Egypt which saw the swiftest movement toward an economy based on the growing of cash crops, and in the same period the amount of cotton grown increased by more than 200%. As well as providing ready cash to the Ottoman government (and landowners), the increase of cash crop production saw the economy of the Ottoman East Mediterranean tied not only to traditional trading partners such as the French at Marseilles, but to ports as far away as Liverpool and Bristol in the United Kingdom.

With the rise in revenue came the diversifications of the functions of state. As the Ottoman economy began to increase in sophistication, it was clear that the state had some role in the facilitation of positive conditions. The first postal service in the Empire came into being in 1817 by decree of the Sultan, and this was aided by a system of roads not seen in the region since the Roman Empire. Although trade in the inland areas of the empire was still hampered by difficult terrain and banditry, the improving conditions did contribute to economic growth as well as increasing government control within the countryside. The Porte was moving toward an internal monopoly of power in larger areas of the country, at least in the “core” areas. However, in outlying provinces such as the outer areas of the Balkans, the half-nomadic territories bordering Iran, as well as the vast swathes of desert throughout the country, the control of the central government remained theoretical at best.

In these outlying areas, local notables continued to act as “tyrants” toward the locals. A petition to the Sultan dated in 1824 note the plight of an Armenian village near Malatya, who had been the victims of extortion as well as kidnapping from nearby Kurdish nomads. There was little enough action on these outlying areas of the empire to stop events like this occurring, particularly when the victims were Christian. This sometimes led to emigration on the parts of the Christians, commonly involving the movement of Slavic peoples in the North into Austrian borders, of that of Armenians into the more secure Iran. In Greece, the harsh treatment received by the population had descended into outright revolt by 1816. Originally dismissed as “bandits” by the Ottoman authorities, Greek Revolutionaries inspired by ideas from Europe fought a desperate struggle for independence that was only defeated after six years of bloody conflict. For the first time in centuries, the Greek Revolt presented an alternate vision of independence for the Christian peoples under Ottoman rule.

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - The Ottoman Empire is simultaneously in a better and worse position than her OTL counterpart by 1830. Internally she is a more centralised state, with a more powerful executive. She has leveraged this power to crush the Greeks before European Powers could intervene, though the blow to her reputation has been done and a general desire for independence cannot be squashed as easily as a physical rebellion can. The Ottoman Empire also has to worry about the more powerful Austrians even as the threat from Iran seems to diminish too.

U know, since Burmese is very similar to Chinese, maybe the Qing, if they try hard enough, can take it.

Threadmarks

View all 59 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Political Culture and Society in Iran - 1831 to 1846 The Third Revolutionary Wars - Europe 1832 to 1838 Changing Tides - The Middle East 1832 to 1844 India - 1831 to 1856 Iranian Society under the Afsharids - 1800 to 1847 The Second Great Turkish War - 1845 to 1849 Growing Vulnerabilities - East Asia 1831 to 1857 The Mahdist Uprising in Fars - 1848 to 1852

Share: